History of Spanish journalism

The history of the Spanish press, understood more as a positivist study of the historical archive of periodicals than as a history of journalism or communications, began around the 15th or 16th centuries in a scattered fashion with manuscripts and the woodcut printing of relaciones de sucesos.[note 1][1][2] Shortly after, the invention of the printing press brought the printing of the first gazettes, although the beginning of journalism in Spain is usually considered to be 1661, the year of the appearance of the Gazeta de Madrid or Gaceta de Madrid,[note 2][3][4][5] From then on, the so-called "old journalism" would develop until 1789, characterized by the dominance of the State. In the 19th century, the business press began to appear, competing with the workers' press and the partisan press, all of which suffered a crisis from 1898 onwards, culminating in the disappearance of numerous newspapers at the beginning of the Civil War. Once democracy was restored after the 1978 Constitution, big media companies completely took over Spanish newspapers.

Up until the 17th century[edit]

The history of journalism in Spain begins with the Romances noticieros,[note 3][6][7] which reported the events of the Granada War in the 15th century. In the 16th century, xylography or wood engraving allowed for the mass and inexpensive publication of all kinds of brief writings. Thus began the publication of relaciones de sucesos by people paid by a municipal council to write, in an adorned manuscript, a report or record of any religious festivity, inauguration, important visit, commemoration, celebration, or memorable event to serve as a memento for the inhabitants, as well as avisos,[note 4][8][note 5][9] which were handwritten reports also paid for and sent from time to time to nobles who wished to be informed of any important event that took place in the Court during their enforced absence.

News reporting began with handwritten letters about the events of the conquest of Granada and continued with reports related to the New World, when pamphlets were printed on the first victories of the Spanish conquerors in the Americas. Perhaps the first relacionero[note 6] was humanist Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, who between 1488 and 1526 wrote no fewer than 812 letters that incorporated many news elements. This type of news correspondent was relatively frequent in the courts during the 17th century, and the notices written by Jerónimo de Barrionuevo, Andrés de Almansa, or José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar have been preserved. The news agencies of the time were places called mentideros[note 7][10] in the Court: Gradas de San Felipe[note 8]—the stairs of the now-defunct Convento de San Felipe el Real next to the Puerta del Sol—which specialized in military affairs and weapons expertise, and was very close to the Calle del Correo street, where couriers arrived carrying the news; Losas de Palacio[note 9]—next to the now-defunct Royal Alcázar of Madrid—where news about the king, the royal family, and nobility were shared; and Representantes,[note 10] where theater people used to gather: artists, actors, poets, and writers, located at the confluence of the Calle del Prado and Calle del León streets. That is why the men of letters of the time, such as Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Góngora, or Quevedo looked for houses nearby to live in.

It was also around this time that the mercurios[note 11] or gacetas[note 12] started to appear, a sort of bulletin that reported on the news of important trade fairs or ports with heavy traffic. In 1625, Avisos de Italia, Flandes, Roma, Portugal y otras partes appeared in Seville from 28 July to 3 August, and in 1641, Jaume Romeu published a translation of the Gazette de France from the French into Catalan–Gaseta vinguda a esta ciutat de Barcelona, per l’ordinari de París, vui a 28 de maig, any 1641. Traduïda del francès en nostra llengua catalana.—[note 13] which can be considered the first weekly publication to appear in the Iberian Peninsula.[11]

Moreover, John Joseph of Austria, prime minister to Charles II, took an interest in the popularity and influence that such gazettes were acquiring in society and thus started to advertise himself by publishing gazettes. He saw in this medium a way to cement his position and satisfy his interests and, for this purpose, he hired Francisco Fabro Bremundán, the first known Spanish gazetteer, to write and print the first Spanish gazette in 1661, the Relación o gaceta de algunos casos particulares, así políticos como militares, sucedidos en la mayor parte del mundo, published once a month, although in Zaragoza it continued as a weekly publication in 1676.[12][13]

But the death of John Joseph of Austria and revenge by his enemies put the publication on hold for a while. It was resumed, however, under the title of Gaceta Ordinaria de Madrid, although Fabro already had a competitor: the Nuevas Ordinarias by Sebastián Armendáriz. In 1697, after Fabro's death, his newspaper continued to be published without interruption as the Gazeta de Madrid or Gaceta de Madrid and, with an occasional change of title, it continues to be printed today as the Boletín Oficial del Estado.[14] On the other hand, it is worthy of note that newspapers in Spanish were not only published in Spain; thus, it should come as no surprise that the oldest known Jewish newspaper is the Gazeta de Ámsterdam, published in Spanish between 1675 and 1690 for the Spanish-Portuguese people that arrived in the Netherlands, although there was a distinct lack of news of Jewish interest.[15]

18th century[edit]

Gazettes began to appear in all major cities throughout the 17th and 18th centuries and soon the contents grew more diversified and widespread, although at this time newspapers were very expensive and were only within the reach of a minority. However, it was undoubtedly one of the most important ways in which enlightened ideas and bourgeois ideology entered Spain. Taking into account that, at this time, 80 percent of the population was illiterate, readers of "periodical papers" were an enlightened minority composed of nobles and clergymen, members of the royal bureaucracy, army officers, and some sectors of the middle class such as doctors, lawyers, professors, and merchants.

During the eighteenth century, three periods stood out:

- Between 1737 and 1750: the consolidation of the press in Spain, with the appearance of the first newspapers, such as El Diario de los Literatos.

- Between 1750 and 1770: the time of maturity and specialization, such as the Diario de Madrid.

- Starting in 1770: the time of decadence; although some interesting publications were born in 1774, linked to the boom set forth by Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes of the Sociedades Económicas de Amigos del País,[note 14] many publications disappeared due to political events and the situation abroad (the French Revolution).

Two types of publications were clearly distinguished: the educated press (periodicals) and the popular press (almanacs and forecasts).

The educated press or periodicals were printed with the permission of the Council of Castile and were subject to ecclesiastical censorship.[16] They could be bought in bookstores or street stalls or be read in cafés, and they were sold by the blind, who had a monopoly on their distribution.[2]

Political and military information was in the hands of two official newspapers: Gaceta de Madrid and Mercurio Histórico y Político. Private publications mainly dealt with cultural or economic issues. They almost always supported an advanced ideology and their readers were an enlightened and bourgeois minority.

The execution of the French royal family led to an increase in censorship and the temporary suspension of the press: on 24 February 1791, King Charles IV of Spain banned the publication of all press materials except official newspapers.[17]

But the bourgeoisie also created popular publications that, already existing in the 17th century, evolved throughout the 18th century: almanacs and forecasts. These were illustrated booklets with engravings that were distributed by the thousands in towns and cities and offered, under the guise of reporting on the weather, the most varied contents: apart from the meteorological forecast for the year, they included data on the phases of the moon, thoughts, standards of conduct, and instructions and teachings on the most varied trades. They attracted the attention of the public with sensationalist titles and had two sections: La introducción al Juicio del año, a prediction of what was going to happen that year according to the stars, and El Juicio del año, a sort of star chart by seasons, months, and days. They are valuable today because they represent a compilation of popular culture and a way of spreading bourgeois values among the lower classes. But their dangerous nature led Charles III of Spain to prohibit their publication in 1767 on the pretext that they were vain and useless reading materials for the people. These publications did not disappear in the nineteenth century, but their purpose changed since the bourgeoisie had a much more effective and direct means for spreading their ideas: popular newspapers. The most famous almanacs were those of Diego de Torres Villarroel, who revived and updated the genre with his Ramillete de astros (1718) by turning the Juicio del año into a fictitious narrative in which fantastical characters made the prediction, taking advantage of the opportunity to insert descriptions, monologues, and other varied materials.

El Diario de los Literatos (1737) was a cultural and literary publication that lasted until 1742. It fought against baroque ideas and supported the work of Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro and Ignacio de Luzán. Its purpose was emitir un juicio ecuánime sobre todos los libros que se publiquen en España.[note 15] It had 400 pages, in book format, cost 4 to 5 reales, and had a print run of between 1,000 and 1,500 copies in circulation. Juan de Iriarte and other scholars of the time wrote for it. It was formed by a group of "well-known writers, desirous of reforming (...) the decadent literature of the eighteenth century" who "published a kind of magazine, which merited the protection of Philip IV (...)." It was modeled after the Parisian Journal de Savants.[18]

In 1738, Salvador José Mañer started translating the Mercurio Histórico y Político from the French.[19] Then, in his printed work in 1774, Juan de Iriarte criticized Mañer for his poor-quality translations. In 1784, already larger in size, its title was changed to Mercurio de España and it has been, with the exception of La Gaceta and El Diario de Madrid, the newspaper that has survived the longest.

El Diario Noticioso, Curioso, Erudito, Comercial y Político was the first daily publication in Spain. It consisted of two sections, one for spreading the news, including opinion pieces that were often translations from the French, and another containing economic information, where sales, rentals, offers, demands, etc. were announced. On 17 January 1758, by royal privilege, Manuel Ruiz de Uribe y Compañía was granted permission to publish it in Madrid. Its first issue was dated 1 February 1758.[20] It was edited by Francisco Mariano Nipho, a restless, erudite, multi-subject author of encyclopedic curiosity, who has come to be considered the first professional journalist in Spanish literature and who published almost a hundred works, twenty of which were periodicals. In 1788, the Diario Noticioso, Curioso, Erudito y Comercial, Político y Económico changed its title to Diario de Madrid.[17]

There was also press that specialized in economic matters, since enlightened ideas supported reforms in this field. El Semanario Económico (1765–1766) spread the technical advances for the improvement of industry and diverse economic texts. On the other hand, the literary press was very widespread. Some works that stood out included El Diario de los Literatos, which dealt with literary criticism of published books, and El Pensador, created by José Clavijo y Fajardo, who started a kind of costumbrista journalism with typically Spanish themes, such as tertulias and refrescos,[note 16][21] courtship, superstition, and behavior in church. It dealt with issues such as the education of both women and men, the role and behavior of teachers, and criticized the autos sacramentales.[note 17] In the first issues, he used the pen name D. Joseph Álvarez y Valladares. In 1797, the Semanario de Agricultura y Artes appeared, the first 17 volumes of which were published by Juan Antonio Melón. Starting on 4 July 1805, the professors from the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid[note 18] Simón de Roxas Clemente y Rubio, Francisco Antonio Zea, and the brothers Claudio Boutelou and Esteban Boutelou got involved. This newspaper was aimed at parish priests so that they would spread agricultural doctrines.

In 1786, the Correo de los Ciegos de Madrid was born, which was then known as Correo de Madrid since 1787.[22] Among articles of the current literary, scientific, technical, and economic matters of the era, there were also progressive articles on social criticism and customs by El militar ingenuo,[note 19] the pen name of Manuel María de Aguirre, an enlightened and radical admirer of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and a consummate critic of the estate society and the political superstructure, according to Antonio Elorza. He longed for the separation of powers and the restructuring of society and decried Juan Bautista Pablo Forner's Oración apologética por España y su mérito literario, criticizing institutions and denouncing injustice, inequality, and ignorance. The Cartas marruecas by José Cadalso were published (posthumously) for the first time in its pages.

The most influential of all newspapers (it was copied by figures such as Manuel Rubín de Celis, Pedro Centeno, and José Marchena Ruiz de Cueto) was El Censor by lawyers Luis María García del Cañuelo (of a malcontent and aggressive nature) and Luis Marcelino Pereira (an expert on economic issues) (1781).[23] It had encyclopedist, liberal, regalist, and Jansenist influences, and dared to question legislative and religious policies and principles. It engaged in profound social criticism of institutions and questioned the statist structure of society. Therefore, it had to fight constantly to obtain a printing license and then against censorship and opposition by the conservative power, represented by official apologist Juan Bautista Pablo Forner. The latter was parodied in Oración apologética por la África y su mérito literario. It also published a fake Carta marrueca by Cadalso and the utopia of the Ayparchontes. Despite all of this, it went on to have eight volumes and 167 speeches, although it was put on hold three times and was continued by a series of imitators such as El Corresponsal del Censor, El Observador by José Marchena Ruiz de Cueto, influenced by Jeremy Bentham's utilitarianism, defender of physiocracy and of natural law or jusnaturalism, as well as equally opposed to Fornerian apologists. In fact, according to José Miguel Caso González, El Censor covered up a well-formed enlightened pressure group, those who were habitués of the Countess of Montijo's salon: Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Juan Meléndez Valdés, Antonio Tavira y Almazán, José de Vargas Ponce, and Félix María de Samaniego. They are the ones responsible for some of the speeches, especially Meléndez and Jovellanos, the latter under the pseudonym Conde de las Claras.[note 20]

El Memorial Literario, in its three eras—since 1784—a monthly publication of 123 pages, was a literary and scientific magazine that was run by Joaquín Ezquerra and Pedro Pablo Trullench and had as its source the Reales Estudios de San Isidro.[note 21] It combined the defense of national interests with constructive criticism, including interesting scientific news. El Diario de las Musas by Luciano Comella and El Espíritu de los Mejores Diarios by Cristóbal Cladera; El Semanario Erudito by Antonio Valladares de Sotomayor and the Gabinete de Lectura Española by Isidoro Bosarte (which introduced each issue with a "prologue")—both from 1787—are compilations of old classic texts such as El Cajón de Sastre by Nifo. Juan José López de Sedano, who collected Spanish literature classics in his anthology Parnaso Español, published El Belianis Literario (1765)— a satire of the publications of the time—under the pseudonym Patricio Bueno de Castilla.

In the 18th century, the press is a phenomenon essentially limited to Madrid, Andalusia, Murcia, Valencia, and Zaragoza. The other provinces hardly have anything to report. It is peculiar that Catalonia or the Basque Country do not have many examples from this period either. On 24 February 1791, all unofficial newspapers were banned by a Royal Resolution signed by José Moñino, 1st Count of Floridablanca.[24] This led to protests by the main publishers, who were thus ruined and were angrily demanding economic compensation (a pension) or a job. Only the three official newspapers, Gaceta de Madrid, El Mercurio, and Diario de Madrid, remained. This ban was partly lifted a year later, in 1792, allowing for the publication of El Correo Mercantil de España y sus Indias by Eugenio Larruga and Diego María Gallard, but it remained in effect until 1795. The press would not flourish again in a manner comparable to the 1780s, not until 1808 with the War of Independence.[24]

The concept of public opinion ceases to be understood in this period with the sense of fame or reputation. Rather, it designates an attitude of social criticism by the members of the bourgeoisie, who demand more power and political representation through newspaper columns: the press and opinions are clearly a bourgeois phenomenon.

Paul Guinard, in his La presse espagnole de 1737 à 1791. Formation et significaticon d'un genre, Paris: Institut d'Études Hispaniques, 1973, distinguishes four types of 18th-century press:

- Presentative: It persuades readers of the interest of the publication in a personalized manner.

- Informative: It is the voice of the government and thus offers biased or partial information—Gaceta de Madrid, Mercurio Histórico.

- Didactic: The didactic genre aims to educate the reader, sometimes in a picturesque manner, such as with fictional or conventional letters, dialogues, imaginary journeys, utopias—the Monarquía columbina, the Viaje al país de los Ayparchontes, the Zenit, the Sinapia found among the papers of the Count of Floridablanca—allegorical or satirical dreams, and especially speeches and essays, a chain of reflections on a central theme with room for digressions, anecdotes, etc.

- Polemic: It takes part in the controversies of its time, sometimes using parodies, which heightens the comical effect. For instance, the controversy surrounding apologists in Spain.

War of Independence and the reign of Ferdinand VII[edit]

During the 19th century, the eighteenth-century press—didactic, utilitarian and costumbrista—began to acquire a definite political tinge. The role of the press in the spread of liberal ideas was decisive, although it had to fight tooth and nail with the censorship imposed by the last vestiges of the Ancien Régime, embodied in the person of Ferdinand VII since, after the French Revolution, there was a conservative reaction throughout Europe and absolutism imposed itself again. There was a bout of freedom of the press during the War of Independence (1808–1814) since the Cortes of Cádiz recognized this freedom in 1810 and especially with the decree of freedom of the press of 26 October 1811. Citizens wanted to know what was happening in the sessions of the Cortes, etc. All of this led to the proliferation of periodical publications of various tendencies: liberal newspapers such as Semanario Patriótico by Manuel José Quintana, El Conciso by Gaspar María de Ogirando, or El Robespierre Español by Pedro Pascasio Fernández Sardino; anti-constitutionalists such as El Censor General and even afrancesados,[note 22] such as the Gaceta de Sevilla, the Diario de Barcelona, or the Diario de Valencia, edited for a while by Pedro Estala.

With the return of Ferdinand VII of Spain and the reaction of the Manifiesto de los Persas, all journalistic activity was interrupted once again. On 25 April 1815, all unofficial publications were banned. From then on, the stages of repression and freedom of the press alternated, coinciding with the absolutist and liberal periods, respectively.

During the brief period of the Trienio Liberal,[note 23] revolutionary and exalted (exaltados) political newspapers, such as El Zurriago or La Tercerola, both edited and partially written by Félix Mejía, started to appear next to newspapers controlled by moderates, such as the Miscelánea de Comercio, Artes y Literatura by Javier de Burgos, El Espectador, El Universal, or by afrancesados like José Mamerto Gómez Hermosilla, Sebastián Miñano, and Alberto Lista, who wrote what is probably the most intellectual and dense publication of the period, El Censor.

This resurgence was also nipped in the bud by the rise of the Holy Alliance with the army known as the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis in 1823. In 1834, after the death of Ferdinand VII, the liberals who had been expelled in 1823 returned to Spain. These exiles not only brought romantic ideas, but also the new ways of doing journalism of the English: newspapers before 1835 barely included any information at all apart from political or scientific topics. They usually had a small format, were written in a single column, and their overall appearance was rather dull. However, from this date on, others started to appear that looked more like the ones that exist today.

Although almost all of them had a short-lived existence, between 1808 and 1814 there was an abundance of publications, since the press would go on to become an important element of the revolutionary-constitutionalist movement by:

- Making political projects known,

- Making readers feel that they belonged to the community,

- Making them aware of the country's problems.

With the return of Ferdinand VII in 1814, the so-called Sexenio Absolutista[note 24] began, during which all of the reforms that had been carried out were ignored and liberal thought was forced to go underground. To speak of journalism in this period was to speak of the official press, since newspapers that had other ideologies had been closed down.

The Trienio Liberal (1820–1823) began with the victory in 1820 of Rafael del Riego's uprising in Las Cabezas de San Juan and the swearing-in of the Constitution of 1812 by Ferdinand VII. That same year, the freedom of the press was proclaimed—whereby everything that did not constitute the ordinary press (pamphlets, flyers) went underground—and in 1822 all possible crimes related to the journalistic activity (libel, slander, etc.) were typified. These measures contributed to a sudden wave of printed materials, in which publications that supported the various liberal factions were predominant.

The most important mastheads of this period were:

- Moderate liberals:

- El Universal, known for its measurements as the sabanón[note 25] (31 x 21 cm, which was huge compared to the usual size at the time)

- El Censor, run by Alberto Lista

- El Imparcial

- El Periódico de las Damas, from which women were called upon to instill in their children the values of the Constitution. Although (or perhaps because) it broke with the classic nature of women's publications, it failed and no more than three issues were ever published.

- Exalted liberals, which introduced an original element in the Spanish press: graphic design (caricatures and jokes with political connotations).

- El Eco de Padilla, the means of expression of the secret society of the Confederation of Spanish Comuneros or Hijos de Padilla.[note 26]

- El Zurriago was a very radical, critical, and satirical newspaper that, with its caricatures, reached the limits of what was permitted.

In 1823, with the intervention of the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis, Ferdinand VII embraced absolutism once again. It was the start of a new period, marked by the censorship imposed during the Ominous Decade or Calomardian Decade, in which the only newspaper that was allowed was the Diario de Avisos de Madrid—a variant or continuation of the first Spanish newspaper, the Diario Noticioso, Curioso, Erudito, Comercial y Político (better known as the Diario de Madrid), founded by the pioneer of journalism Francisco Mariano Nipho in 1758 and that disappeared definitely on 31 December 1814. The Diario de Avisos de Madrid, together with the also official Gazeta de Madrid or Gaceta de Madrid shared the same absolutist and servile style. However, in 1828, the king began a timid policy of liberalization brought on by his need to win over liberals in his fight against his brother, the Infante Carlos María Isidro, to remain in power. From that date on, it was allowed to publish romantic and costumbrista mastheads, which would be a means of expression for liberal thought.

- Romantic publications:

- El Duende Satírico del Día, by Mariano José de Larra, 1828.

- El Pobrecito Hablador, by Mariano José de Larra, 1831.

- El Guadalhorce (1839), which was the medium of the movement in Málaga.

- La Alhambra (1839–1843), who had José de Espronceda as collaborator.

- Costumbrista publications:

Reign of Isabella II and the Democratic Sexennium[edit]

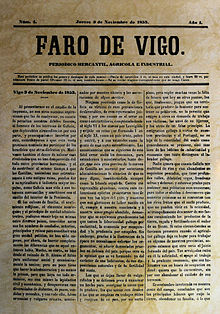

Although from 1833 until the Restoration, newspapers would try to be controlled and used by successive governments, it is no less true that it was during this period when democratic ideas (Saint-simonianist utopian socialism) began to appear in the liberal press through articles by certain collaborators. This ideological seepage would continue during the regency of Baldomero Espartero (1840–1843) and the reign of Isabella II (1843–1868). Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of this period, as far as this topic is concerned, is the birth of informative journalism, the access by the working class to the press, and the appearance of a series of mastheads that have it as their natural recipient. The Faro de Vigo, the oldest newspaper in Spain at the beginning of the 21st century, started to be published in 1853.

Between 1868 and 1875 (the reign of Amadeo I and the First Republic), nearly 600 newspapers appeared in Spain. This information boom took place because the revolutionary process began with the freedom of the press, which would be included in the Constitution of 1869.

Despite everything, either in exile or under censorship, the press sparked public opinion and made democratic bourgeois institutions evolve little by little, not only in Europe (the revolutions of 1830 and 1848), but also in Spain (the aforementioned of 1812 and the one in 1868). In Spain, in particular, censorship was applied in an extreme manner against Carlist publications and, at the other end of the political spectrum, against those of the Democratic Party. After the victory of liberalism, all Western countries recognized (around 1881) freedom of expression and passed press laws. On the other hand, technology created new distribution channels, and improvements to the printing press made possible larger, cheaper, and more colorful editions, illustrated with beautiful engravings. In addition, the spread of the reading habit among the lower classes—thanks to public education, which was one of the victories of the bourgeois revolutions, as well as the aforementioned improvements that made the press cheaper—allowed for the press to spread to these classes of society, creating a model known as the mainstream press, with its most visible manifestation being the so-called feuilleton or serial novel. From 1868 onwards, there continued to be opinion newspapers, supporters of a political party or a political leader. However, an informative press evolved to be the most successful among readers and the one that achieved the highest circulation numbers. The external aspect of these newspapers was more entertaining. Their contents were no longer limited to political issues, but also new sections appeared pertaining to literary criticism, puzzles, anecdotes, and humor. They devoted more space to advertising and inserted feuilletons (novels published in instalments, or so-called serial novels), which were very popular among the lower classes.

After the revolution of 1868 (La Gloriosa[note 27]), the Constitution of 1869 recognized freedom of the press and numerous newspapers and magazines started to appear. The boom of Spanish journalism began with the arrival in Spain of the first rotary printing press in 1875, to be used for Rafael Gasset's El Imparcial. This was followed by a series of prestigious publications: El Comercio of Gijón (1877), El Liberal of Bilbao (1879), La Vanguardia of Barcelona (1881), El Noticiero Universal of Barcelona (1888), Heraldo de Madrid (1890), Blanco y Negro of Madrid (1891), and Heraldo de Aragón of Zaragoza (1895)

In 1883, the Printing Law established by the liberal government of Práxedes Mateo Sagasta was also favorable to periodical publications. All this, along with more sophisticated technical media, allowed periodicals to experience a real boom (around 600 registered publications) during the Sexenio Democrático.[note 28]

Although the majority of the population was illiterate and print runs were very small (they never exceeded 15,000 copies), they were widely distributed thanks to the tradition of reading aloud, the existence of reading rooms, and the custom of reading newspapers in coffeehouses, ateneos,[note 29] and tertulias. In Madrid and in the provincial capitals, a wider reading public began to grow as education spread. The women's press started to develop in 1868. After the victory of the 1868 revolution, schools were opened to educate the lower classes and the first workers' newspapers appeared. Then, noteworthy publications emerged, such as La Flaca magazine. The style of La Flaca was copied by other magazines in Madrid and Barcelona, among which stood out: L'Esquella de la Torratxa (1872), La Filoxera (1878), El Loro (1879), La Viña (1880), El Motín (1881) by José Nakens, La Mosca (1881), La Broma (1881), La Tramontana (1881), Acabose (1883), and Las Dominicales del Libre Pensamiento (1883–1909) by Fernando Lozano Montes.

A well-documented and serious press for elite circles was also developed, represented by El Imparcial (1867) and El Liberal (1879). La Correspondencia de España (1859) stood out as an independent newspaper. El Imparcial did as well, with its literary supplement, Los Lunes de El Imparcial, which published—between 1879 and 1906 and under the management of José Ortega Munilla—works by the most important authors of the time: José Zorrilla, Juan Valera, Ramón de Campoamor, Emilia Pardo Bazán, and Rubén Darío. Los Lunes de El Imparcial also launched to stardom the most important authors of regenerationism and the generation of '98: Miguel de Unamuno, Azorín, Pío Baroja, and Ramón María del Valle-Inclán.

Journalism during the Restoration[edit]

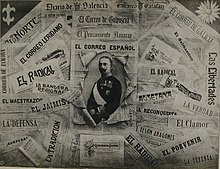

Newspaper giants started to emerge during the Restoration, favored by those in power, which would serve to support the new political situation.[25]

Starting in 1880, new media emerged that were quantitatively and qualitatively different from those of the 19th century, which represented the birth of the 20th century information age. Around this time, various Western countries passed bourgeois press laws that recognized freedom of expression and organized their information structure around national news agencies that had close ties to governments and supplied information to newspapers. Under that predominance of news agencies, all media outlets covered the same topics. The birth of news agencies spurred some changes in how information spread: the creation of the global telegraph network resulted in the ubiquity of information and the tendency towards uniformity typical of information in the 20th century, and the press gained objectivity.

At that time—the late 19th century and early 20th century—the so-called mass press evolved in the United States and some European countries. Newspapers increased their circulation dramatically, they included numerous advertising pages, got established in large buildings, and obtained profits unheard of until then. In addition, they abandoned the old formulas and assumed new roles in 20th-century society: they became goods for use and consumption, sold at low prices, and offered their readers an attractive and well-finished product. Their repeated presence in society turned them into instruments of great influence and this excess of power would allow them to serve as the catalyst for manipulations of all kinds. It is in this context that yellow journalism emerged.

In the late 19th century, there was a type of newspaper with characteristics that did not differ much from those of today's newspapers. There was an abundance of information, better, varied, and more extensive, fed by correspondents in each provincial capital and in European capitals, with telegraphic news and sometimes two editions: one in the morning and another in the evening. Newspapers now had a greater variety of sections: accident and crime reports, business, announcements, excerpts of sessions at the Cortes, travels and interviews, daily entertainment section, literary articles, poetry works, short stories, newsletters, critiques.

In Catalonia, La Vanguardia (from 1881 to the present) was created in 1881 by brothers Bartolomé Godó and Carlos Godó y Pié. In 1896, Rafael Roldós created Las Noticias, which would rival La Vanguardia in Barcelona.

According to statistics from 1887, there were 1,128 newspapers and magazines circulating in Spain that year.

Newspaper ABC, founded by Torcuato Luca de Tena in 1903, began as a weekly and then became a daily in 1905. It had a magazine format—it was even stapled—and its ideology was monarchist and conservative. El Debate, published by Editorial Católica and created by Ángel Herrera Oria in 1910, defended Catholic ideas. It lasted until the beginning of the Civil War. It was a quality newspaper with political, religious, and cultural concerns. Moreover, it paved the way for the creation of the first school of journalism. El Sol was founded in 1917 by Nicolás María de Urgoiti. José Ortega y Gasset served as the main intellectual inspiration, and Mariano de Cavia and Salvador de Madariaga, among others, collaborated in its pages. El Sol wanted to restore the country's political and social situation by having a sister evening paper, La Voz, which had a more light-hearted tone. La Nación was a newspaper of reference for the right wing between 1925 and 1936. Its workshops were burned down in the violent climate prior to the Civil War. The link between the press and the political parties was sometimes not as clear as it might have seemed:

One of the most famous press reports in the history of journalism during the Second Republic was the one by Ramón J. Sender on the massacre of anarchists in Casas Viejas for newspaper La Libertad. The value of that series of articles has not changed, but its political significance has done so, taking into account that the Republican newspaper was at the time owned by Juan March and therefore it was quite advantageous to use the event in order to stoke a fire in which the government of Manuel Azaña could burn. A similar thing was happening with leftist newspaper La Tierra, in whose pages collaborated anarcho-syndicalists and communists, going day after day against the regime, duly subsidized by the monarchist right wing for such a holy task.

It is worthy of note that most of these were business newspapers that—apart from seeking to have an impact on public opinion and defend certain interests and ideologies—sought economic profitability and used advertising as their main means of financing. They can be considered as mass press due to their contents and objectives, but they did not reach the large print runs that characterized foreign newspapers due to the lack of a wide reading public: Spain was still a scarcely urbanized country, with high illiteracy rates. But from 1910 onwards, Spanish newspapers started to evolve into mass newspapers: they began to use a less stilted and more dynamic language, and to present certain lexical and stylistic changes. Moreover, their layout became more attractive, especially with the appearance of photographs. Their contents reflected the tastes of popular culture: public entertainment (football, bullfighting, the theatre, etc.), political events, references to other media (the press and the cinema), a billboard section, etc. There were also special pages or supplements on topics such as economics, variety shows, art, sports, agriculture, women's issues, and children's issues. On the other hand, the impact of the war in Europe increased the interest in foreign issues. Thus, Spanish newspapers were split between those that were partisans of the Allies or pro-Allied and the Germanophiles or pro-Germany. The first women journalists appeared in Spain during this period. Some of those who stood out included Carmen de Burgos, editor of Madrid's Diario Universal; Sofía Casanova, at ABC; and Concha Espina, who worked for Buenos Aires's El Correo Español and now-defunct Spanish newspapers La Libertad and La Nación, as well as Cantabria's El Diario Montañés.

There were also newspapers linked to the labor movement, such as El Socialista (of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, PSOE), Tierra y Libertad (of the anarchist Federación Anarquista Ibérica, FAI),[note 30] Solidaridad Obrera (of the Catalan Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, CNT[note 31]), or Mundo Obrero (of the Communist Party of Spain, PCE).

According to a 1914 statistic, there were 138 periodicals defined as "far left" circulating in Spain that year, including two anarchist, 26 socialist, 79 republican, 10 federalist, 3 republican-socialist, 15 radical, and 3 reformist newspapers. On the other hand, the "far right" side included 136 publications, among them 89 Catholic, 38 traditionalist or Carlist, and nine fundamentalist papers. There were 79 newspapers defined as liberal, 52 as conservative, 16 as regionalist, and eight as "undefined monarchist." There were also 154 newspapers that defined themselves in politics as "independent," although some of them were considered as monarchist and others as republican, according to the general opinion.

The children's press appeared in 1917 with weekly magazine TBO, whose name spelled out (tebeo) has become synonymous in Spain with the genre known worldwide as comic book.

In the period between wars, totalitarian movements and ideologies arose in various Western countries (German Nazism, Italian Fascism, Russian Communism, Spanish Francoism, etc.). Two different information models were established: the model of these totalitarian states, based on propaganda as one of the fundamental means to control the masses through biased information and the absolute control of all media, and the model of the hesitant liberal democracies such as England, where freedom of expression was recognized.

Photojournalism emerged due to competition from new media such as film, radio, and television. Photographic images were no longer a mere ornament but an alternative language. Media outlets were used as a way to escape from the surrounding reality: they offered 90% entertainment and 10% enjoyable information, and aimed to take readers away from their day-to-day problems.

Second Republic[edit]

Much of the current historiography refers to the Second Spanish Republic as a "Republic of journalists." Indeed, in the Constituent Courts of 1931 there were 47 journalists. After university professors, they were the largest professional group, with the exception of lawyers.

Certainly, the eventful life of the Second Spanish Republic did not allow it to be an example of immaculate freedom of expression. Censorship continued to operate and repressive measures were widespread. In any case—and especially seen from today's perspective—the newspapers of the time attacked their adversaries with an aggressiveness that would seem inconceivable today. The accumulated violence in Spanish society, of which the press was but a mere reflection, would lead to a definitive rupture: the military uprising against the legally constituted government was to definitively truncate the penultimate attempt at modernizing Spain.

Most of the major newspapers welcomed with hope the new situation arising from the municipal elections of 12 April 1931. Even among the openly monarchist newspapers, El Debate applied the doctrine of the "de facto" government of Leo XIII and accepted the new regime. On the other hand, ABC was reluctant from the very beginning. The provisional government assumed all powers and issued a broad amnesty. The Provisional Legal Statute that was to govern political life until the proclamation of the new Constitution in December 1931 already recognized all individual rights, including, of course, the right of expression, although the government reserved for itself a "regime of control" of these rights. Article 34 of the draft bill for the Constitution sanctioned freedom of expression, while Article 10 stated: Corresponde al Estado español la legislación y podrá corresponder a las Regiones autónomas la ejecución en la medida de su capacidad política a juicio de las Cortes, sobre las siguientes materias: (...) 10. Régimen de prensa. Asociaciones, reuniones y espectáculos públicos.[note 33] As a result of the burning of convents on 11 May, newspapers ABC and El Debate were suspended. The former would reappear on 3 June and the latter, on 20 May.

Shortly after the approval of article 26 of the Constitution, related to the matter of religion—pertaining to the separation of church and state and related matters like intellectual freedom, freedom of religion, and the regulation of marriage and divorce, among others—a draft bill called De Defensa de la República[note 34] was passed on 24 October. It considered the spreading of news that could disturb the peace and public order as acts of aggression against the Republic. There were numerous fines and suspensions on the right and left wings as a result of this law. Shortly before the proclamation of the Republic, El Sol and La Voz had been acquired by a group of monarchist figures. In any case, both newspapers adhered to the new regime. Within the landscape of the daily press during the period of the Republic, newspaper Ahora occupied a prominent place. It began to be published on 16 November 1930, to coincide with the Republican Jaca uprising. It was established with the clear intention of competing from more progressive positions with newspaper ABC. Although somewhat larger in size, Ahora also printed several pages in rotogravure and its front page was always occupied by an up-to-the-minute photograph. It also displayed, at the beginning, a monarchical loyalty that would later turn into respect for the new republican regime.

Ahora was owned by Luis Montiel Balanzat who, more than a journalist, should be called a newspaper entrepreneur, having started in the paper industry and then in the graphic arts sector. In 1926, Montiel launched literary newspaper La Novela Mundial, which was followed by others and finally, in January 1928, by weekly magazine Estampa. Montiel was also behind one of the most popular Spanish sports publications, weekly magazine As, which appeared in June 1932. Faced with the danger of being overwhelmed by the left or the right, the Republic needed a loyal press. After the Crisol adventure, Urgoiti founded Luz with major participation from the Agrupación al Servicio de la República,[note 35] with José Ortega y Gasset, Gregorio Marañón, and Ramón Pérez de Ayala. As El Sol and Crisol before it, Luz was going to be run by Félix Lorenzo.

In September 1932, El Socialista began to spread the news that, financed by wealthy Catalan business owner Luis Miquel, a journalistic "trust" was going to be created with El Sol, La Voz, and Luz.[26] Mexican journalist Martín Luis Guzmán, who had been Pancho Villa's secretary[27] and who had Azaña's ear at the time,[28] put the latter in contact with Luis Miquel. After the failure and the uprising of 10 August, Miquel managed to take over the ownership of El Sol and La Voz, apparently with the threat of implicating their royalist owners in the attempt. On 14 September, Luz announced a "bid for new capital" which would energize it, as well as the replacement "for health reasons" of director Félix Lorenzo by Luis Bello Trompeta. With Luis Miquel as president of the board of directors and Martín Luis Guzmán as manager, the "trust" that grouped the three newspapers was effectively established. In any case, the adventure was going to end in economic failure. Besides, Bello was going to have serious disagreements with the socialist members of government, which would lead to his dismissal as head of Luz on 8 March 1933, causing a difficult crisis in the editorial office: Luis Miquel himself was going to be forced to assume the management and Nicolás Urgoiti, the deputy management. Shortly after, Miquel lost the title to El Sol and La Voz by edict of a Madrid court. The new company appointed Fernando García Vela, a loyal collaborator of Ortega y Gasset, as editor of El Sol, and confirmed Enrique Fajardo (also known by the pseudonym Fabián Vidal) as editor of La Voz. Luz, in whose direction Miquel had been succeeded by Corpus Barga, ceased publication on 8 September 1934.[29]

Civil war[edit]

During the Civil War, both in the Republican and the Nationalist factions, official institutions were established that were exclusively dedicated to spreading propaganda: the Ministry of Propaganda in the former and the Delegación Nacional de Prensa y Propaganda[note 36] in the latter. In the geographic area occupied by each side, only loyal newspapers could be published, and they were subjected to strict military censorship. The oddest case was that of ABC: its edition in Seville continued to respond to its traditional ideology, supporting the side of the rebels. Meanwhile, its building in Madrid was expropriated and the newspaper was published with the same masthead, but in support of the Republican cause (controlled by the Republican Union). Moreover, the facilities of El Debate were used to publish Mundo Obrero. There were, however, honest journalists who questioned the violence and absurdity of the war from a purely human perspective, such as democrat Manuel Chaves Nogales, whom both sides wanted to execute.

There was a satirical newspaper, La Ametralladora, that was distributed in the rebel trenches. Humorists such as Miguel Mihura and Álvaro de Laiglesia collaborated on the paper, and later both continued during Franco's regime with La Codorniz, which remained the longest-standing publication in the genre until it was surpassed by magazine El Jueves. On the other side, in the republican zone, the more elitist El Mono Azul[note 37] was published. It included contributions from poets of the Generation of '27.

Francoism[edit]

The victors learned from the war that the media had to fulfill the social role of public service. The theory of the social responsibility of the media was then developed. From 1945 to 1970, there was a period of economic expansion that had repercussions on the development of the information sector. Democratic states defended freedom of expression and, at the same time, established media control regulations. At the same time, they became owners of newspapers, radio stations, and public television channels. The information business grew, and information companies increased their power. This was favorable to media concentration—progressively fewer companies owned increasingly more media outlets—despite control by the States that enact antitrust laws. However, while freedom of expression was definitively established in democratic States, this did not represent the situation in Francoist Spain, where the 1938 press law—which was designed to have an iron grip on publications during the Civil War—was maintained.

During World War II, a large part of the Spanish press came to be controlled by the head of propaganda of the German Embassy in Madrid, the pro-Nazi Jew Josef Hans Lazar. The main exponent of this situation was newspaper Informaciones, which became the primary focus of anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi publicity in Spain.

The most important characteristics of the press during this period were prior censorship and the so-called "mottos" through which the Ministry of Information and Tourism could order the insertion of articles, even editorials, with a certain tendency or content. The headlines of Madrid newspapers represented the minimum plurality that was allowed among the regime's various families:

- Arriba: pro-government, considered the medium of the Movimiento Nacional. It was sometimes used to test the control of one of the families (the gironazo—an article published by José Antonio Girón de Velasco on 28 April 1974).[note 38]

- Hoja del Lunes, the only newspaper that could be distributed on Monday since Sunday rest was mandatory for all others. The Madrid edition was printed in the shops of Arriba (previously in the shops of Ya). It had been published continuously since 1930 by the Madrid Press Association, and there were counterparts throughout Spain (the Royal Decree of 1 May 1926 granted the various press associations the capability to publish them in order to cover the needs of their associates). They ceased to be published in the 1980s, when newspapers began to appear every day.

- El Alcázar: far right—what came to be known as the Búnker—except for a brief liberal period between 1966 and 1969; first published by a company with ties to Opus Dei and, from 1975 onwards, by the Confederación Nacional de Ex Combatientes.[note 39]

- Ya: Catholic—which in the First Francoism meant National Catholicism and after the Second Vatican Council distanced itself from the regime—successor of El Debate; loosely controlled by the Bishops' Conference and the Asociación Católica de Propagandistas,[note 40] inspired by journalist and cardinal Ángel Herrera Oria.

- Pueblo: with close ties to the Spanish Syndical Organization—which in the First Francoism meant national syndicalism and in its final stage went on to be considered, in some manner, "pro-worker"—led in that last period by Emilio Romero, who flirted with left-wing opposition circles without abandoning Falangism. It was the most read newspaper in Spain after La Vanguardia and ABC.

- ABC: owned by the Luca de Tena family, conservative and monarchist, with the presence of Luis María Anson, who would end up running it. Franco's decision for the succession to the Spanish throne to go to Juan Carlos de Borbón instead of his father Juan de Borbón—exiled in Estoril—put a strain on the regime's relationship with the newspaper, which was seized on occasion (1966). ABC was the Madrid newspaper with the largest circulation, surpassed only by La Vanguardia at a national level.

- Madrid: the one that ended up showing the greatest determination to defy the regime, taking advantage of the timidly liberal atmosphere of Manuel Fraga's press law (1966). In spite of this, it ended up being fined and closed down in 1971. Its building was demolished with a spectacular explosion.

- Informaciones (newspaper): an evening newspaper that was considered the most progressive, after the closure of the daily Madrid. Forges' cartoons were famous.

- Cambio 16: weekly magazine published from 1971 with a liberal orientation, both in an economic and political sense. During the last two years of the dictatorship, it became the most progressive newspaper in Spain and achieved an enormous increase in its circulation.

- Triunfo: magazine published between 1946 and 1982, founded and run throughout its existence by José Ángel Ezcurra. It started as an entertainment weekly but turned into a general information magazine in its heyday in 1962, soon becoming the intellectual benchmark of Spain at that time.

Apart from the very active press in Barcelona (where La Vanguardia and Solidaridad Obrera were renamed La Vanguardia Española and Solidaridad Nacional), in other provinces there were many newspapers, among them El Norte de Castilla, ran by Miguel Delibes, and where Francisco Umbral began his journalistic career.

The 1966 press law and the independent press[edit]

During the early years of Francoism, the press was tightly controlled by the Ministry of Information and Tourism through the censorship mechanisms established by the 1938 press law, a situation that began to change in 1962. It was this year that Minister of Information Gabriel Arias-Salgado was dismissed because of international criticism of his press campaign against the participants in the so-called Contubernio de Múnich.[note 41][30] He was succeeded by Manuel Fraga Iribarne, at that time considered one of the most liberal representatives of the regime. In the following years, Fraga promoted a new press law, approved in 1966, which abolished prior censorship and mottos. However, this liberalization was only partial, since the publication of certain opinions, for example, open criticism of the regime, remained forbidden. In addition, there was reinforcement of the principles of civil and even criminal liability of any editor who violated the provisions of the law. Thus, the intention was to replace the system of prior censorship with a system of self-censorship by the newspapers themselves.

Nevertheless, in the following years, several newspapers tried to explore the limits of this new freedom of expression through provocative texts and more or less covert criticism of the regime. In this context, newspapers Madrid, El Alcázar, and Nuevo Diario were particularly important. The three newspapers, which formed the self-styled independent press, were run by liberal-leaning members of Opus Dei who tried to take advantage of the ties of this Catholic organization to liberalize the regime (despite the fact that Opus Dei ministers were indeed part of the most conservative core within Franco's cabinet). However, from 1968 onwards, the defiance of the independent press to the regime caused dramatic reactions by the Ministry of Information, which finally led to changes in the publishing companies of newspapers El Alcázar and Nuevo Diario in 1969 and to the closure of Madrid in 1971.

After Fraga's dismissal as Minister of Information in 1969, censorship and newspaper seizures grew again in intensity. Nonetheless, in the last years of the regime, more established newspapers (such as La Vanguardia and, to a lesser extent, ABC and Pueblo) also took advantage of the relative liberalism of the press law to diversify the political discourse and criticize the regime's policies, albeit always in a moderate or underhanded manner. Thus, at the time of Franco's death, newspapers were the place where the most controversial and important political debates in the country held. While political institutions such as the Cortes were still controlled by the orthodox sectors of the regime, the press had become, according to an expression of the time, a "paper parliament."

Humor and escape[edit]

During the Francoist period, there was a flourishing of children's periodicals, with TBO surviving among them. In the fifties, other children's magazines appeared as well, such as: Pulgarcito, Tío Vivo, and El DDT, from Editorial Bruguera (a refuge for many adults), and Pumby or Jaimito, from Editorial Valenciana, and others. Some were clearly politically framed within the regime, such as Flechas y Pelayos. The evolution of La Codorniz (intellectual in origin, coming from Falangism, the artistic avant-garde currents, and surrealism) towards a bitter and disenchanted sort of humor brought it more than a few problems with censorship, and gave way in the seventies to other adult humor publications that continued to push the envelope of what was allowed, from a clearly progressive position: Hermano Lobo (magazine), El Papus, and in 1977, El Jueves, the longest-standing humor magazine in Spain.

A special role was played by the press that was considered less serious or more popular, which could be compared to the escapist role played in literature by subgenres (the Western novels of Marcial Lafuente Estefanía or the romance novels of Corín Tellado), and in radio by the radio dramas (Ama Rosa, Simplemente María), a genre in which Guillermo Sautier Casaseca stood out. Although much less than the media that evolved later, the escapist press was predominantly sensationalist, with its reliance on photographs and, depending on the case, color, and glossy, higher quality paper. El Caso focused on accident and crime reports, concentrating on the most sordid aspects, and pushing the limits of good taste as far as the censorship allowed. The readership of weekly gossip magazines was predominantly made up of women. Apart from its broad distribution, it reached a massive casual or regular reading public in doctors' offices and hairdressing salons, where discussions were often held to comment on its contents. It was segmented (in both price and social standing) into an aristocratic version (¡Hola!, 1944-, which also has international versions) and other more popular ones (Diez Minutos, 1951-, or best-selling Pronto, 2014-). Also important are Semana (1940-) and Lecturas (1917-), the longest-standing of the Spanish gossip magazines.

Transition and democracy[edit]

The year 1970 marked the beginning of a crisis that ushered in the information society in which we are living today. The development of new technologies had an impact on all media outlets. There was a clear predominance of US agencies and television networks. Many states that maintained public media outlets went on to privatize them, leaving them in the hands of large business groups (PRISA, Grupo Zeta, Grupo Godó, Grupo Correo, Prensa Española, these latter two merged in September 2001 into Grupo Vocento).

In Spain, after the transition to democracy, the press experienced a major boom with the appearance of all kinds of publications. Apart from newspapers with a long-standing history, such as ABC or La Vanguardia, new ones appeared, like El País (Grupo Prisa, thought to have close ties to the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party) or El Mundo (deemed to have close ties to the People's Party), which soon turned into solid media companies and power groups. Others were more short-lived, such as Diario 16, which emerged from the transition of magazine Cambio 16. It was in this newspaper that Pedro J. Ramírez started his career as director, later going on to work at El Mundo. Other newspapers were created more recently, such as La Razón—very conservative leaning, originally run by Luis María Anson, who had left ABC due to disagreements with the ownership and who ended up also leaving his new newspaper after having made it grow quite successfully. Luis María Anson and Juan Luis Cebrián (at that time directors of ABC and El País) were simultaneously (in 1996) appointed full fellows of the Royal Spanish Academy, in what was seen as a recognition of the contribution to the language by the written press and an attempt by the institution to appear neutral in the media and political debate.

In Barcelona, other newspapers emerged, in addition to the traditional La Vanguardia (from Grupo Godó, considered non-nationalist and conservative). These included El Periódico de Cataluña (from Grupo Zeta, considered non-nationalist and progressive), and Avui (with ties to Catalan nationalism). In the Basque Country, there were El Correo (formerly known as El Correo Español-El Pueblo Vasco, from Vocento group, considered non-nationalist and conservative), Deia (with ties to the Basque Nationalist Party), and Egin—closed by court order for its ties to ETA and because some journalists who were published in it were also prosecuted, such as Pepe Rei—whose space was occupied by Gara, also belonging to Herri Batasuna.

As has been the case throughout the Modern Age, the list of journalists with high literary quality is very extensive, with names such as Antonio Gala, Francisco Umbral, Miguel Delibes, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Luis Álvarez, Fernando Savater, Raúl del Pozo, Almudena Grandes, Juan José Millás, José Antonio Marina, Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, Mario Vargas Llosa, Jorge Edwards, Gabriel Albiac, Jorge Berlanga, Antonio Burgos, Miguel García-Posada, David Gistau, Luis Antonio de Villena, Manuel Hidalgo Ruiz, Eduardo Mendicutti, Rosa Montero, Javier Ortiz, Carmen Rigalt, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Vicente Verdú, Manuel Vicent, Espido Freire, Lucía Etxebarría, Francisco Nieva, Juan Marsé, José Luis Alvite, Pedro García Cuartango, Julián Lago, José Luis Gutiérrez, Alfonso Ussía, Juan Manuel de Prada, Manuel Martín Ferrand, Alfonso Armada, Alfonso Rojo, Arturo Pérez-Reverte, Félix de Azúa, Javier Marías, Mónica Fernández Aceytuno, Ignacio Camacho, as well as columnists who introduce arguments in the debate of ideas in society: Jaime Campmany, Eduardo Haro Tecglen, José Luis Martín Prieto, and others.

The presence of the written press in the events of recent years has not been exclusively as a reflection of reality, but often anticipates and provokes it: the most famous journalistic scandals had to do mostly with campaigns led by El Mundo (under the guise of investigative journalism) regarding the last socialist governments of Felipe González for cases of corruption (the Guerra case,[note 43] the Filesa case,[note 44] and the Luis Roldán case).[31] The newspaper also played an important role in exposing paramilitary group GAL and its so-called "dirty war" when it published a comprehensive series of articles. Moreover, it also reported on the controversies about the 2004 Madrid train bombings. Luis María Anson made statements in which he attributed the fall of Felipe González to a journalistic campaign conceived between himself and other journalists such as Pedro J. Ramírez, and which ended up taking José María Aznar all the way to the presidency.[32]

The traditional format of the written press has been challenged in recent years by the appearance of two new competitors: the spread of the Internet and electronic publishing (being a substantial part of the model of La Marea and Público, as well as Eldiario.es), and alternative media outlets such as blogs and, secondly, the rise of free newspapers, distributed in the streets and not in the usual places such as newsstands (20 minutos, Metro, ADN, Qué!). Less successful was a newspaper conceived as a method of social integration for homeless people, who acted as salespersons as an alternative to begging (La Farola).[33]

Leading newspapers today[edit]

General interest[edit]

Sports[edit]

- Marca

- Diario AS

- Sport

- Mundo Deportivo

- L'Esportiu (in Catalan)

Economic[edit]

General interest in provinces or autonomous regions[edit]

- El Periódico de Catalunya: it has two versions—Catalan and Spanish—and has offices in Barcelona, Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, the Valencian Community, Andorra, and La Franja of Aragón

- Ara: the most read daily newspaper written exclusively in Catalan; with offices in Barcelona, Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, the Valencian Community, Andorra, and La Franja of Aragón

- El Correo: with offices in Bilbao, Biscay, Gipuzkoa, Álava, Navarre, Lower Navarre, Labourd, Soule, Valle de Villaverde, Comarca del Ebro, Treviño enclave, Miranda de Ebro

- El Diario Vasco: with offices in San Sebastián, Gipuzkoa, Biscay, Álava, Navarre, Lower Navarre, Labourd, Soule, Valle de Villaverde, Comarca del Ebro, Treviño enclave, Miranda de Ebro

- El Diario Montañés: Cantabria

- La Verdad: Murcia

- Ideal: Eastern Andalusia (Almería, Granada, and Jaén)

- Hoy: Extremadura

- Diario Sur: south of Andalusia (Málaga, Axarquía, Marbella, Costa del Sol, Melilla, Gibraltar)

- La Rioja: La Rioja

- El Norte de Castilla: Castile and León, mainly Valladolid, Palencia, Segovia, Salamanca

- El Comercio: Asturias

- Las Provincias: the Valencian Community

- La Voz de Cádiz: Cádiz

- Heraldo de Aragón: Zaragoza, Aragon

- El Periódico de Aragón: Zaragoza, Aragon

- Diario de Navarra: Pamplona, Navarre

- Diario de Noticias de Navarra: Pamplona, Navarre

- La Provincia: Las Palmas, Canary Islands

- Canarias7: Las Palmas, Canary Islands

- Última Hora: Palma de Mallorca, Balearic Islands

- Diario de Mallorca: Palma de Mallorca, Balearic Islands

- La Tribuna de Albacete: Albacete, Castilla-La Mancha

- Diario de León: León

- El Día de Valladolid: Valladolid

- La Gaceta Regional de Salamanca: Salamanca

- Diario de Burgos: Burgos

- La Opinión-El Correo de Zamora: Zamora

- Diario Palentino: Palencia

- Diario de Ávila: Ávila

- El Adelantado de Segovia: Segovia

- Heraldo-Diario de Soria: Soria, sold along with El Mundo throughout Soria Province)

- La Voz de Galicia: A Coruña, Galicia

- Nós Diario: Santiago de Compostela, Galicia

- Diario de Pontevedra: Pontevedra

- Faro de Vigo: Vigo, province of Pontevedra

- El Progreso: Lugo

- La Región: Ourense, Galicia

See also[edit]

- History of journalism

- History of newspaper publishing

- List of the oldest newspapers

- Contemporary history of Spain

Notes[edit]

- ^ English: news pamphlets

- ^ English: Madrid Gazette, which would be replaced in 1936 by the Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE) or the Official State Gazette

- ^ English: news-bearing ballads

- ^ English: announcements; Italian: avviso, plural: avvisi

- ^ English: Avvis [sic]: Handwritten sheets with various news, that were sent more or less regularly to paying customers. They are called by the name given to them in Venice, Italy.

- ^ English: news pamphleteer

- ^ English: rumor mills

- ^ English: Steps of San Felipe

- ^ English: The Palace Flagstones

- ^ English: Representatives

- ^ English: lit. mercuries (referring to Mercury, the messenger of the gods in Roman mythology)

- ^ English: gazettes

- ^ English: Gazette brought to this city of Barcelona, by stagecoach from Paris, this day May 28th 1641. Translated from the French into our Catalan language.

- ^ English: Economic Societies of Friends of the Country

- ^ English: To issue an impartial judgment on all books published in Spain

- ^ English: lit. refreshments, a social gathering where beverages—usually hot cocoa, tea, and coffee, along with sweet pastries—were served

- ^ English: sacramental ordinances

- ^ English: Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid

- ^ English: The Ingenuous Soldier

- ^ English: The Count of Plain Words

- ^ English: Royal Studies of San Isidro

- ^ English: Francophiles, lit. Frenchified

- ^ English: lit. Liberal Triennium, or Three Liberal Years

- ^ English: lit. Absolutist Sexennium or absolutist six-year term

- ^ English: large sheet

- ^ English: Sons of Padilla

- ^ English: the Glorious Revolution

- ^ English: lit. Democratic Sexennium, or a democratic six-year term

- ^ English: lit. athenaeum, a type of cultural center or cultural association

- ^ English: Iberian Anarchist Federation

- ^ English: National Confederation of Labor

- ^ Supporters of Jaime, Duke of Madrid, previously known as Carlists, and also known as traditionalists

- ^ English: It falls on the Spanish State to legislate and it might fall on the autonomous regions to execute, to the extent of their political capability, in the opinion of the Cortes, about the following matters: (...) 10. Press regulations. Associations, meetings, and public spectacles.

- ^ English: On the Defense of the Republic

- ^ English: Group to the Service of the Republic

- ^ English: National Delegation of the Press and Propaganda

- ^ English: Blue Overalls—which was contradictory, since blue was the color of the uniform worn by the members of the militias as well as the proletariat

- ^ With this article, Girón managed to mobilize the far right and denounce the "false liberals infiltrated in the administration and in the highest state offices."

- ^ English: National Confederation of Former Combatants

- ^ English: National Catholic Association of Propagandists

- ^ English: Munich Conspiracy. This was the derogatory name—coined by Falangist newspaper Arriba—in which the Francoist dictatorship referred to the Fourth Conference of the European Movement International held in Munich, Germany, in June 1962.

- ^ English: Madrid Press Association

- ^ In which Juan Guerra, the brother of then Deputy Prime Minister Alfonso Guerra, was prosecuted for corruption.

- ^ A corruption scandal in which a group of companies was created to cover the costs of the 1989 electoral campaign of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party.

References[edit]

- ^ García de Enterría et al. 1995.

- ^ a b Sánchez-Moliní, Luis (13 November 2016). "Sevilla perteneció a la red de ciudades europeas donde nació el periodismo". Diario de Sevilla (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Gazeta nueva de los sucesos políticos y militares de la mayor parte de la Europa" (PDF). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). 1 January 1661. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Historia de la prensa". Ministry of Education and Science (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Langa-Nuño 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Valenciano 2017.

- ^ Marías 2017.

- ^ "Historia de la prensa-Glosario". Ministry of Education and Science (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

Avvis [sic]: Hojas manuscritas con noticias diversas, enviadas de forma más o menos regular, a clientes que pagaban por éstas. Reciben el nombre que se les dio en Venecia (Italia).

- ^ McIntyre 1987.

- ^ "Un rincón donde se disfrazan las verdades". La Voz de Cádiz (in Spanish). 9 December 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Llanas 2004.

- ^ Lamarque 1966, p. 238.

- ^ "La historia de Gazeta". Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Nuevas ordinarias de los sucesos del Norte". Biblioteca Nacional de España (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Pach-Oosterbroek 2014, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Schulte 1968, p. 70.

- ^ a b Schulte 1968, p. 109.

- ^ Schulte 1968, p. 87.

- ^ Schulte 1968, p. 86.

- ^ Schulte 1968, p. 93.

- ^ Pérez Samper 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Schulte 1968, p. 108.

- ^ Schulte 1968, p. 107.

- ^ a b Schulte 1968, p. 111.

- ^ Rueda Laffond, Galán Fajardo & Rubio Moraga 2014.

- ^ "Luis Miquel compra LUZ a Nicolá Mª de Urgoiti para crear un Trust de periódicos azañistas con AHORA, EL SOL y LA VOZ". La Hemeroteca del Buitre (in Spanish). 15 September 1932. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Martín Luis Guzmán". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Alcubierre Moya, Beatriz; Ramírez Garrido, Jaime (1 December 2011). "Martín Luis Guzmán: A la sombra de la Revolución". Nexos (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Fracaso mediático de Luis Miquel: Se retira del diario LUZ que pasará a ser una publicación gráfica con Corpus Barga". La Hemeroteca del Buitre (in Spanish). 30 June 1933. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ López 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Iglesias, Leyre (28 October 2022). "El legado negro de Felipe González: "Fueron años de impunidad"". El Mundo (Spain) (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Anson: "Para terminar con González se rozó la estabilidad del Estado"". El País (in Spanish). 17 February 1998. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Aguirre, Begoña (28 January 1995). "200 indigentes obtienen ingresos con la venta callejera de 'La Farola". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2024.

Bibliography[edit]

- García de Enterría, María Cruz; Ettinghausen, Henry; Infantes, Víctor; Redondo, Agustín (1995). Las Relaciones de sucesos en España (1500-1750) (PDF). First Symposium of the International Society for the Study of News Pamphlets (SIERS) (in Spanish). Alcalá de Henares, Spain: University of Alcalá Press and Publications de la Sorbonne. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- Lamarque, Pilar (January–June 1966). "Algunas noticias sobre Francisco Fabro Bremundans". Revista de archivos, bibliotecas y museos (in Spanish). 73 (1). Madrid, Spain: Biblioteca Nacional de España: 237–244. ISSN 0034-771X. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Langa-Nuño, Concha (2010). "Claves de la historia del periodismo" (PDF). In Reig, Ramón (ed.). La dinámica periodística : perspectiva, contexto, métodos y técnicas (PDF) (in Spanish). Seville, Spain: University of Seville, Department of Journalism II, Department of Contemporary History. pp. 10–40. ISBN 9788493760007. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Llanas, Manuel (2004). Books and publishing in Catalonia: notes and considerations. Translated by Stacey, Andrew. Barcelona, Spain: Gremi d'Editors de Catalunya. ISBN 8493230065.

- López, Carlos (2016). Franco's Spain and the Council of Europe (PDF) (Report). Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l'Europe. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- McIntyre, Jerilyn (1987). "The Avvisi of Venice: Toward an Archaeology of Media Forms". Journalism History. 14 (2–3). Taylor & Francis: 68–77. doi:10.1080/00947679.1987.12066646. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Marías, Clara (12 January 2017). "Las muertes en torno a los Reyes Católicos en el Romancero trovadoresco y tradicional". Neophilologus. Vol. 101, no. 1. Springer. pp. 399–416. doi:10.1007/s11061-016-9517-1.

- Pach-Oosterbroek, Hilde (2014). Arranging reality: The editing mechanisms of the world's first Yiddish newspaper, the Kurant (Amsterdam, 1686–1687) (PhD thesis, externally prepared thesis). University of Amsterdam. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Pérez Samper, María Ángeles (2001). "Espacios y prácticas de sociabilidad en el siglo XVIII: Tertulias, refrescos y cafés de Barcelona". Cuadernos de Historia Moderna (in Spanish) (26). Servicio de Publicaciones (Universidad Complutense de Madrid): 11–55. ISSN 0214-4018. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- Rueda Laffond, José Carlos; Galán Fajardo, Helena; Rubio Moraga, Ángel L. (2014). "3. La democratización de la palabra y la imagen (1830-1914)". Historia de los medios de comunicación (in Spanish). Spain: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 978-84-206-8952-4.

- Schulte, Henry F. (1968). The Spanish Press, 1470-1966: Print, Power, and Politics. University of Illinois Press.

- Valenciano, Ana (2017). A vueltas con estilo oral: los primeros romances noticieros (PDF). V Colóquio Internacional do Romanceiro, "Viejos son, pero no cansan: Novos estudos sobre o romanceiro" (in Spanish). Coimbra, Portugal: Fundación Ramón Menéndez Pidal. pp. 399–409. doi:10.34619/xv1h-k112. ISBN 978-989-8968-06-7. Retrieved 24 March 2024.