Holland House

| Holland House | |

|---|---|

Holland House in 1896 | |

| Location | London |

| Built | 1605 |

| Built for | Sir Walter Cope |

| Architectural style(s) | Elizabethan, Jacobean |

| Owner | Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 29 Jul 1949[1] |

| Reference no. | 1267135 |

51°30′9″N 0°12′9″W / 51.50250°N 0.20250°W

Holland House, originally known as Cope Castle, was a great house in Kensington in London, situated in what is now Holland Park. Created in 1605 in the Elizabethan or Jacobean style[a] for the diplomat Sir Walter Cope, the building later passed to the powerful Rich family, then the Fox family, under whose ownership it became a noted gathering-place for Whigs in the 19th century. The house was largely destroyed by German firebombing during the Blitz in 1940; today only the east wing and some ruins of the ground floor still remain.

Design

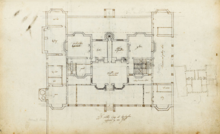

Cope commissioned the house in 1604 from the architect John Thorpe.[b] The building was of a common shape for large houses of the time,[3] containing a centre block and two porches.[4] The building received a large expansion between 1625 and 1635 at the direction of Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, Cope's son-in law and owner of the building, who added two wings and arcades.[4]

In 1629, Rich commissioned Inigo Jones[5] to design and the master mason Nicholas Stone to carve a pair of Portland stone piers, in order to support large wooden gates for the house.[c] The piers, still extant, take the form of Doric columns on pedestals, and originally supported carved griffins bearing the arms of the Rich family and Cope family, symbolising the two families' union.[8]

The piers have been moved to new positions on several occasions. While their exact original position is not known, a survey in 1694 showed them as being on the drive leading to the house's main entrance on its south side. In 1848, as part of a major restructuring of the house by the 4th Lord Holland, the piers were moved to the eastern side of the house. Following the house's destruction in the Second World War, and the conversion in 1959 of the remains of the east wing into a youth hostel, the piers were returned to the south side.[8]

Creation and role in the Civil War

At the time of its creation in 1605, the house presided over a 500 acres (200 ha; 0.78 sq mi) estate that stretched from Holland Park Avenue to the current site of Earl's Court tube station, and contained exotic trees imported by John Tradescant the Younger.[9] Following its completion, Cope entertained the king and queen at it numerous times; in 1608, John Chamberlain, the noted author of letters, complained that he "had the honour to see all, but touch nothing, not so much as a cherry, which are charily preserved for the queen's coming."[10]

Following the death of his son Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, in November 1612, King James I spent the night at Cope Castle, being joined the following day by his son Charles and daughter Elizabeth, and her fiancé Frederick V, Elector Palatine.[11]

Cope's son-in-law, Henry Rich eventually inherited the house. Rich was granted the titles of Baron Kensington and Earl of Holland by James I, and upon gaining the latter renamed the building to Holland House.[12] He was later beheaded for his Royalist activities during the Civil War and the house was then used as an army headquarters, being regularly visited by Oliver Cromwell. Lord Holland's headless ghost was sometimes reported as haunting the house, carrying his head under his arm.[13]

17th century

King William III had been a lifelong sufferer from asthma, and his condition was exacerbated by the damp air at his court's riverside location in Whitehall.[14] Attempting to improve his health, he decided to move his court. After a short time spent at Hampton Court, he decided to have another home that was near enough to his capital to easily carry out royal business, but not near enough to be the air of London to threaten his health. He considered Holland House for the purpose, and stayed there for some weeks;[d] but eventually decided to purchase Kensington House, the suburban residence of the Earl of Nottingham, known today as Kensington Palace.

18th century

In 1719, Joseph Addison, the English essayist, poet and politician, died in the building. Holland House passed to the Edwardes family in 1721.

At its peak, Cope's estate had comprised some five hundred acres of land, and its southern extent almost reached the Fulham Road.[16] By the time it was purchased by Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, from William Edwardes in 1768, it had shrunk to two hundred acres.[16]

Fox had begun living at the mansion in 1746, and in 1749 obtained a lease from Edwardes of the house and sixty-four acres of land for "99 years or three lives".[16] By 1767, Fox was leasing all of Edwardes' estate north of the Hammersmith road (the modern Kensington High Street), and negotiated a purchase of the land for £17,000, and a further £2,500 paid to the sons of Edward Henry Edwardes, who would otherwise have inherited the estate.[e]

Fox died at Holland House in 1774 and thereafter it was inherited by his descendants.

As 19th-century social centre

Under the 3rd Baron Holland and his wife Elizabeth, the house became noted as a glittering social, literary and political centre with many celebrated visitors such as Byron, Thomas Macaulay, the poets Thomas Campbell and Samuel Rogers, 'Conversation' Sharp, Benjamin Disraeli, Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott. The figure of the political and historical writer John Allen was so associated with the house that he was known as Holland House Allen and there was a room in the house named after him.[9]

The prestige of Holland House extended to British colonies. In 1831 Henry John Boulton, who was born in Holland House, erected a baronial-like home in the city of Toronto. Henry John Boulton had been born in the famous English house, and he commemorated that fact by naming the Toronto home Holland House.[17]

...this strange house, which presents an odd mixture of luxury and constraint, of enjoyment both physical and intellectual, with an alloy of small désagréments.... Though everybody who goes there finds something to abuse or ridicule in the mistress of the house, or its ways, all continue to go; all like it more or less; and whenever, by the death of either, it shall come to an end, a vacuum will be made in society which nothing will supply. It is the house of all Europe; the world will suffer by the loss; and it may be said with truth that it will "eclipse the gayety of nations".

— Charles Greville, The Greville Memoirs[18]

Harper's New Monthly Magazine described Holland House as having had a "Gilt Chamber", where "the figures over the fireplace were painted in flesh colour wherever bare; the rest was in shaded gold. The lower marbles of the fireplace were black, and the upper ones were Sienna; the capitals and bases of the columns and pilasters were gilt, and the groundwork from which all the glittering decoration rose was white."[19]

The house's dower house, known as Little Holland House, became the centre of a Victorian artistic salon presided over by the Prinseps and the painter George Frederic Watts.

The title of Baron Holland became extinct with the death of the fourth Baron, Henry Edward Fox, in 1859. However, his widow continued to live there for many years, gradually selling off outlying parts of the park for development. In 1874, the estate passed to a distant Fox cousin, Henry Fox-Strangways, 5th Earl of Ilchester.

In 1804 the garden of Holland House saw one of the earliest successful growths of the dahlia in England. Whilst in Madrid, Lady Holland was given either dahlia seeds or roots by botanist Antonio José Cavanilles.[20] She sent them back to England, to Lord Holland's librarian Mr Buonaiuti at Holland House, who successfully raised the plants.[21][22]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Holland House had the largest private grounds of any house in London, including Buckingham Palace.[4] The Royal Horticultural Society regularly held flower shows there.

Destruction and present day status

In 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended the debutante ball of Rosalind Cubitt, daughter of Roland Cubitt, 3rd Baron Ashcombe and the former Sonia Keppel, the ball was described as the last great ball held at the house.[23][24] A few weeks later, on 7 September, the German bombing raids on London that would come to be known as the Blitz began. During the night of 27 September, Holland House was hit by twenty-two incendiary bombs during a ten-hour raid. The house was largely destroyed, with only the east wing, and, miraculously, almost all of the library remaining undamaged. Surviving volumes included the sixteenth-century Boxer Codex.

Holland House was granted Grade I listed building status in 1949,[1] under the auspices of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947; the Act sought to identify and preserve buildings of special historic importance, prompted by the damage caused by wartime bombing.[25] The building remained a burned-out ruin until 1952, when its owner, Giles Fox-Strangways, 6th Earl of Ilchester, sold it to the London County Council (LCC). The remains of the building passed from the LCC to its successor, the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1965, and upon the dissolution of the GLC in 1986 to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Today, the remains of Holland House form a backdrop for the open air Holland Park Theatre, home of Opera Holland Park. The YHA (England and Wales) "London Holland Park" youth hostel was located in the house but has now closed. The Orangery is now an exhibition and function space, with the adjoining former Summer Ballroom now a restaurant, The Belvedere. The former ice house is now a gallery space. The grounds provide sporting facilities, including a cricket pitch, football pitch, and six tennis courts.

In 1962, the Holland estate sold a piece of land immediately to the south of what is now the sports field for the construction of the Commonwealth Institute.

Timeline

Template:Timeline of Holland House, London

Galleries

-

The south frontage of Holland House

-

The China Room

-

The Dutch Garden

-

A garden with a fountain on the house's west side

-

The north side of the house viewed from its lawn

-

Steps to a garden

-

The Gilded Room, or Gilt Chamber

-

The library

-

The arcade, originally part of the old stables

-

An arcade of roses

-

The main staircase

-

The Swaneries Drawing Room

-

A garden terrace with steps on the house's east side

Notes

- ^ Sources[which?] differ in which of the two closely related styles the house was built.

- ^ The book of Thorpe's designs is held by Sir John Soane's Museum, containing a ground-plan of the mansion with the identification "Sir Walter Coapes at Kensington, perfected per me I. T."[2]

- ^ In a notebook of engraver George Vertue (designated "A.b" [6]), who compiled a history of art in the country, he records "Kensington, 23 March 1629. Nicholas Stone undertakes to [make] for the Earl of Holland 2 Peeres of good Portland stone to hang a pair of great wooden gates on for £100."[7][5]

- ^ Several of William's letters to Anthonie Heinsius are dated from Holland House.[15]

- ^ The Survey of Kensington suggests that Fox was able to pay this sum with profits obtained from his office of Paymaster General during the Seven Years' War.[16]

Citations

- ^ a b Historic England (2015).

- ^ Sanders (1908), p. 6.

- ^ Walford (1878), pp. 161–177. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWalford1878 (help)

- ^ a b c Mitton (1903).

- ^ a b Spiers (1919), p. 8.

- ^ Lindsay (1997), p. 242.

- ^ Vertue (1713).

- ^ a b Nolan & Starren (2010).

- ^ a b ODNB (2004).

- ^ Birch (1848), p. 75.

- ^ Birch (1848), p. 205.

- ^ Webb (1921), pp. 292–296.

- ^ Walford, Edward (1878). "Holland House and its history - Old and New London: Volume 5 (pp. 161-177)". British History Online. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Historic Royal Palaces (2012).

- ^ Macaulay (1848), p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Sheppard (1973).

- ^ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 3: The History of Holland House". Landmarks of Toronto Revisited. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Greville (1887), p. 126.

- ^ Harper's (1877), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Forbes (1833), p. 246.

- ^ Hogg (1853), p. 5.

- ^ Salisbury (1808), p. 93.

- ^ MacCarthy (2006), pp. 143–144.

- ^ Mitford (2010), p. 97.

- ^ Victorian Society (2013).

References

- Allen, Elizabeth (September 2009). "Cope, Sir Walter (1553?–1614)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6257. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- Birch, Thomas; Williams, Robert Folkestone (1848). The Court and times of James the First: illustrated by authentic and confidential letters, from various public and private collections. Vol. 1. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- Forbes, James; Russell Bedford, John (1833). Hortus Woburnensis, A Descriptive Catalogue of upwards of Six Thousand Ornamental Plants Cultivated at Woburn Abbey. J. Ridgway.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Greville, Charles (1887). "Chapter XIX". The Greville Memoirs: A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV. and King William IV. Vol. 2. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Elizabethan and later English furniture". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 56 (331). December 1877. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- Historic England. "Holland House (1267135)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- "Origins: From Jacobean mansion to Kensington Palace". Historic Royal Palaces. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- Hogg, Robert (1853). The Dahlia; Its History and Cultivation. Groombidge and Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lindsay, Alexander (1997). Index of English Literary Manuscripts. Vol. 3, John Gay—Ambrose Philips. London: Mansell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7201-2283-X.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1848). "XI". The History Of England From the Accession of James II. Vol. III. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitton, Geraldine Edith (1903). "The Kensington District". In Sir Walter Besant (ed.). The Fascination of London. London: Adam & Charles Black. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nolan, David; Starren, Caroline (2010). "On Public View: A journey around the sculpture of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Salisbury, R. A. (1808-04-05). "Observations on the different Species of Dahlia, and the best Method of Cultivating them in Britain". Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London. 1. London: W. Bulmer & Co.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sanders, Lloyd Charles (1908). The Holland House Circle. London: Methuen & Co. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sheppard, F.H.W. (1973). "The Holland Estate: To 1874". Survey of London: volume 37: Northern Kensington. British History Online. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spiers, Walter Lewis (1919). Finberg, A.J. (ed.). "Notes on the life of Nicholas Stone". The Walpole Society. 7, The Note-book and Account-book of Nicholas Stone, Master Mason to James I and Charles I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vertue, George (1713). Common-place books of G. Vertue. Vol. 2. Add MS 23068-23074. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walford, Edward (1878). "Holland House, and its Historical Associations". Old and New London. Vol. 5. British History Online. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- Webb, E.A. (1921). "The parish: Descendants of Rich and the advowson". The records of St. Bartholomew's priory [and] St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield. Vol. 2. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Listed buildings". The Victorian Society. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- Fiona MacCarthy (5 October 2006). Last Curtsey: The End of the Debutantes. Faber & Faber. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0571228591.

- Deborah Mitford (9 November 2010). Wait for Me!: Memoirs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 97. ISBN 978-0374207687.

External links

Media

- Map of the building (PDF) by Ordnance Survey for the house's entry in Historic England's list of buildings

- Archive film from Pathé News showing the ruins of Holland House after its destruction in the Blitz.

- An iconic photograph of men reading books in the largely undamaged library after the bombing. (Alternative versions: 1, 2)

- Photos from 1952, when the house was sold to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, showing the damaged interior of the house, and workers clearing rubble.

- Photographic gallery of the current appearance of the building

Websites

- Buildings and structures in the United Kingdom destroyed during World War II

- Country houses in London

- Former castles in the United Kingdom

- Former houses in Kensington and Chelsea

- Fox family (English aristocracy)

- Grade I listed houses in London

- Holland Park

- Houses completed in 1605

- Rich family

- Youth hostels in England and Wales

- 17th-century architecture in the United Kingdom

- 1605 establishments in England