Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia between the 4th century AD and the 7th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time; the Huns' arrival is associated with the migration westward of a Scythian people, the Alans.[1] By 370 AD, the Huns had arrived on the Volga, and by 430 the Huns had established a vast, if short-lived, dominion in Europe.

In the 18th century, the French scholar Joseph de Guignes became the first to propose a link between the Huns and the Xiongnu people, who were northern neighbours of China in the 3rd century BC.[2] Since Guignes' time, considerable scholarly effort has been devoted to investigating such a connection. However, there is no scholarly consensus on a direct connection between the dominant element of the Xiongnu and that of the Huns.[1] Priscus, a 5th-century Roman diplomat and Greek historian, mentions that the Huns had a language of their own; little of it has survived and its relationships have mainly been considered the Turkic or Mongolic languages. Numerous other ethnic groups were included under Attila the Hun's rule, including very many speakers of Gothic, which some modern scholars describe as a lingua franca of the Empire.[3] Their main military technique was mounted archery.

The Huns may have stimulated the Great Migration, a contributing factor in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.[4] They formed a unified empire under Attila the Hun, who died in 453; after a defeat at the Battle of Nedao their empire would quickly disintegrate over the next 15 years. Their descendants, or successors with similar names, are recorded by neighbouring populations to the south, east and west as having occupied parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia approximately from the 4th century to the 6th century. Variants of the Hun name are recorded in the Caucasus until the early 8th century.

Origin

The Huns were "a confederation of warrior bands", ready to integrate other groups to increase their military power, in the Eurasian Steppe in the 4th to 6th centuries AD.[5] Most aspects of their ethnogenesis (including their language and their links to other peoples of the steppes) are uncertain.[6][7] Walter Pohl explicitly states: "All we can say safely is that the name Huns, in late antiquity, described prestigious ruling groups of steppe warriors."[8]

The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, who completed his work of the history of the Roman Empire in the early 390s, recorded that the "people of the Huns … dwell beyond the Sea of Azov near the frozen ocean".[9][10] Jerome associated them with the Scythians in a letter, written four years after the Huns invaded the empire's eastern provinces in 395.[11] The equation of the Huns with the Scythians, together with a general fear of the coming of the Antichrist in the late 4th century, gave rise to their identification with Gog and Magog (whom Alexander the Great had shut off behind inaccessible mountains, according to a popular legend).[12] This demonization of the Huns is also reflected in Jordanes's Getica, written in the 6th century, which portrayed them as a people descending from "unclean spirits"[13] and expelled Gothic witches.[14][15]

The 6th-century Roman historian Procopius of Caesarea (Book I. ch. 3), related the Huns of Europe with the Hephthalites or "White Huns" who subjugated the Sassanids and invaded northwestern India, stating that they were of the same stock, "in fact as well as in name", although he contrasted the Huns with the Hephthalites, in that the Hephthalites were sedentary, white-skinned, and possessed "not ugly" features:[17][18]

The Ephthalitae Huns, who are called White Huns [...] The Ephthalitae are of the stock of the Huns in fact as well as in name, however they do not mingle with any of the Huns known to us, for they occupy a land neither adjoining nor even very near to them; but their territory lies immediately to the north of Persia [...] They are not nomads like the other Hunnic peoples, but for a long period have been established in a goodly land... They are the only ones among the Huns who have white bodies and countenances which are not ugly. It is also true that their manner of living is unlike that of their kinsmen, nor do they live a savage life as they do; but they are ruled by one king, and since they possess a lawful constitution, they observe right and justice in their dealings both with one another and with their neighbours, in no degree less than the Romans and the Persians[19]

Since Joseph de Guignes in the 18th century, modern historians have associated the Huns who appeared on the borders of Europe in the 4th century AD with the Xiongnu ("howling slaves") who had invaded China from the territory of present-day Mongolia between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD.[20][21] Due to the devastating defeat by the Chinese Han dynasty, the northern branch of the Xiongnu had retreated north-westward; their descendants may have migrated through Eurasia and consequently they may have some degree of cultural and genetic continuity with the Huns.[22] Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen was the first to challenge the traditional approach, based primarily on the study of written sources, and to emphasize the importance of archaeological research.[23] Thereafter the identification of the Xiongnu as the Huns' ancestors became controversial among some.[24]

The similarity of their ethnonyms is one of the most important links between the two peoples.[1] The Buddhist monk Dharmarakṣa, who was an important translator of Indian religious texts in the 3rd century AD, applied the word Xiongnu when translating the references to the Huna people into Chinese.[25] A Sogdian merchant described the invasion of northern China by the "Xwn" people in a letter, written in 313 AD.[25] Étienne de la Vaissière asserts both documents prove that Huna or Xwn were the "exact transcriptions" of the Chinese "Xiongnu" name.[26] Christopher P. Atwood rejects that identification because of the "very poor phonological match" between the three words.[27] For instance, Xiongnu begins with a voiceless velar fricative, Huna with a voiceless glottal fricative; Xiongnu is a two-syllable word, but Xwn only has one syllable.[28] However, according to Zhengzhang Shangfang, Xiongnu was pronounced [hoŋ.naː] in Late Old Chinese, corresponding well to Huna.[29] The Chinese Book of Wei contain references to "the remains of the descendants of the Xiongnu" who lived in the region of the Altai Mountains in the early 5th century AD.[30] According to De la Vaissière, the Chinese source proves that nomadic groups preserved their Xiongnu identity for centuries after the fall of their empire.[30] Most ancient texts in Europe and Asia, including Chinese, Indian and Islamic studies state that Huns originally came from north of China. According to Edwin G. Pulleyblank, European Huns comprised two groups of tribes with different ethnic affinities and the ruling group that bore the name Hun was directly connected with the Xiongnu.[31]

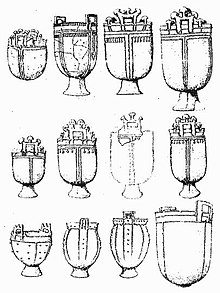

Both the Xiongnu and Huns used bronze cauldrons, similarly to all peoples of the steppes.[32] Based on the study and categorization of cauldrons from archaeological sites of the Eurasian Steppes, archaeologist Toshio Hayashi concludes that the spread of the cauldrons "may indicate the route of migration of the Hunnic tribes" from Mongolia to the northern region of Central Asia in the 2nd or 3rd century AD, and from Central Asia towards Europe in the second half of the 4th century, which also implies the Huns' association with the Xiongnu.[33] The Huns practised artificial cranial deformation, but there is no evidence of such practice among the Xiongnu.[34][page needed] This custom had already been practised in the Eurasian Steppes in the Bronze Age and in the early Iron Age, but it disappeared around 500 BC.[35] It again started to spread among the local inhabitants of the region of the Talas River and in the Pamir Mountains in the 1st century BC.[35] In addition to the Huns, the custom is also evidenced among the Yuezhi and Alans.[36] The lengthy pony-tail, which was a characteristic of the Xiongnu, was not documented among the Huns.[37]

When writing of the relationship between the Xiongnu and Huns, historian Hyun Jin Kim concludes: "Thus to refer to Hun-Xiongnu links in terms of old racial theories or even ethnic affiliations simply makes a mockery of the actual historical reality of these extensive, multiethnic, polyglot steppe empires".[38] He also emphasizes that "the ancestors of the Hunnic core tribes … were part of the Xiongnu Empire and possessed a strong Xiongnu element, and the ruling elite of the Huns … claimed to belong to the political tradition of this imperial entity."[38] Taking into account the historical gap between the Chinese reports of the Xiongnu and the European records of the Huns, Peter Heather states: "Even if we do make some connection between fourth-century Huns and first-century [Xiongnu], therefore, an awful lot of water had passed under an awful lot of bridges during 300 years worth of lost history."[37]

History

Before Attila

The 2nd-century geographer Ptolemy mentioned a people called Chuni (Χοῦνοι or Χουνοί) when listing the peoples of the western region of the Eurasian Steppes.[39][40] The Chuni lived "between the Bastarnae and the Roxolani", according to Ptolemy.[39][40] Edward Arthur Thompson said, the similarity between the two ethnonyms (Chuni and Huns) is only a coincidence: Western Roman authors often wrote Chunni or Chuni in reference to the Huns; East Romans never used the guttural "[x]" at the beginning of their name.[40] Maenchen-Helfen and Denis Sinor also dispute the association of the Chuni with Attila's Huns.[41] However, Maenchen-Helfen proposes that Ammianus Marcellinus referred to Ptolemy's report of the Chuni when stating that the Huns "are mentioned only cursorily in ancient writers".[9][41] He does not exclude either that the Urugundi who invaded the Roman Empire from the steppes to the north of the Lower Danube in 250 AD, according to Zosimus, were identical with the Vurugundi, whom Agathias listed among the Hunnic tribes.[42]

The Romans became aware of the Huns when the Hunnic invasion of the Pontic steppes forced thousands of Goths to move to the Lower Danube to seek refuge in the Roman Empire in 376, according to the contemporaneous Ammianus Marcellinus.[37] Their sudden appearance in the written sources suggests that the Huns crossed the Volga River from the east not much earlier.[10] They invaded the land of the Alans, which was located to the east of the Don River, slaughtering many of them and forcing the survivors to submit themselves to them or to flee across the Don.[43][44][45] The reasons for the Huns' sudden attack on the neighboring peoples are unknown.[46] After rejecting several possible reasons (including a climate change in the steppes and the neighboring peoples' pressure), Peter Heather concludes that the Hunnic Empire developed from "warbands on the make", launching profitable plundering raids, which enabled them to increase their military power and to impose their authority on the neighboring peoples.[47]

After they subjugated the Alans, the Huns and their Alan auxiliaries started plundering the wealthy settlements of the Greuthungi, or eastern Goths, to the west of the Don.[37] The Greuthungic king, Ermanaric, resisted for a while, but finally "he found release from his fears by taking his own life",[48] according to Ammianus Marcellinus.[37] Marcellinus's report refers either to Ermanaric's suicide[49] or to his ritual sacrifice.[37] His great-nephew, Vithimiris, succeeded him.[49] He hired Huns to fight against the Alans who invaded the Greuthungi's land, but he was killed in a battle.[49][44]

After Vithimiris's death, most Greuthungi submitted themselves to the Huns.[49] Those who decided to resist marched to the Dniester River which was the border between the lands of the Greuthungi and the Thervingi, or western Goths.[50] They were under the command of Alatheus and Saphrax, because Vithimiris's son, Viderichus, was a child.[50] Athanaric, the leader of the Thervingi, met the refugees along the Dniester at the head of his troops.[37] However, a Hunnic army bypassed the Goths and attacked them from the rear, forcing Athanaric to retreat towards the Carpathian Mountains.[37] Athanaric wanted to fortify the borders, but Hunnic raids into the land west of the Dniester continued.[37] Most Thervingi realized that they could not resist the Huns.[37] They went to the Lower Danube, requesting asylum in the Roman Empire.[51] The Greuthingi under the leadership of Alatheus and Saphrax also marched to the river.[37] Most Roman troops had been transferred from the Balkan Peninsula to fight against the Sassanid Empire in Armenia.[37] Emperor Valens permitted the Thervingi to cross the Lower Danube and to settle in the Roman Empire in the autumn of 376.[52] The Thervingi were followed by the Greuthingi, and also by the Taifali and "other tribes that formerly dwelt with the Goths and Taifali" to the north of the Lower Danube, according to Zosimus.[52] Food shortage and abuse stirred the Goths to revolt in early 377.[51] The ensuing war between the Goths and the Romans lasted for more than five years.[37]

Support for the Gothic chieftains diminished as refugees headed into Thrace and towards the safety of the Roman garrisons.

After these invasions, the Huns begin to be noted as Foederati and mercenaries. As early as 380, a group of Huns was given Foederati status and allowed to settle in Pannonia. Hunnish mercenaries were also seen on several occasions in the succession struggles of the Eastern and Western Roman Empire during the late 4th century. However, it is most likely that these were individual mercenary bands, not a Hunnish kingdom.[1]

In 395 the Huns began their first large-scale attack on the Eastern Roman Empire.[53] Huns attacked in Thrace, overran Armenia, and pillaged Cappadocia. They entered parts of Syria, threatened Antioch, and swarmed through the province of Euphratesia. The forces of Emperor Theodosius were fully committed in the west so the Huns moved unopposed until the end of 398 when the eunuch Eutropius gathered together a force composed of Romans and Goths and succeeded in restoring peace. It is uncertain though, whether or not Eutropius' forces defeated the Huns or whether the Huns left on their own. There is no record of a notable victory by Eutropius and there is evidence that the Hunnish forces were already leaving the area by the time he gathered his forces.[1]

Whether put to flight by Eutropius, or leaving on their own, the Huns had left the Eastern Roman Empire by 398. After this, the Huns invaded the Sassanid Empire. This invasion was initially successful, coming close to the capital of the empire at Ctesiphon; however, they were defeated badly during the Persian counterattack and retreated toward the Caucasus Mountains via the Derbend Pass.[1]

During their brief diversion from the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns appear to have threatened tribes further west, as evidenced by Radagaisus' entering Italy at the end of 405 and the crossing of the Rhine into Gaul by Vandals, Sueves, and Alans in 406.[53] The Huns do not then appear to have been a single force with a single ruler. Many Huns were employed as mercenaries by both East and West Romans and by the Goths. Uldin, the first Hun known by name,[53] headed a group of Huns and Alans fighting against Radagaisus in defense of Italy. Uldin was also known for defeating Gothic rebels giving trouble to the East Romans around the Danube and beheading the Goth Gainas around 400–401. Gainas' head was given to the East Romans for display in Constantinople in an apparent exchange of gifts.

The East Romans began to feel the pressure from Uldin's Huns again in 408. Uldin crossed the Danube and captured a fortress in Moesia named Castra Martis, which was betrayed from within. Uldin then proceeded to ransack Thrace. The East Romans tried to buy Uldin off, but his sum was too high so they instead bought off Uldin's subordinates. This resulted in many desertions from Uldin's group of Huns.

Alaric's brother-in-law, Athaulf, appears to have had Hun mercenaries in his employ south of the Julian Alps in 409. These were countered by another small band of Huns hired by Honorius' minister Olympius. Later in 409, the West Romans stationed ten thousand Huns in Italy and Dalmatia to fend off Alaric, who then abandoned plans to march on Rome.

Under Attila and Bleda

From 434 the brothers Attila and Bleda ruled the Huns together. Attila and Bleda were as ambitious as their uncle Rugila. In 435 they forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus,[54] giving the Huns trade rights and an annual tribute from the Romans. The Romans also agreed to give up Hunnic refugees (individuals who could have threatened the brothers' grip on power) for execution. With their southern border protected by the terms of this treaty, the Huns could turn their full attention to the further subjugation of tribes to the west.

When the Romans breached the treaty in 440, Attila and Bleda attacked Castra Constantias, a Roman fortress and marketplace on the banks of the Danube.[55] The Eastern Romans stopped delivery of the agreed tribute, and they broke other conditions of the Treaty of Margus. The Hunnic kings turned their attention back to the Eastern Romans. Reports that the Bishop of Margus had crossed into Hun lands and desecrated royal graves further angered the Hun kings. War broke out between the two empires, and the Huns overcame a weak Roman army to raze the cities of Margus, Singidunum and Viminacium. Although a truce was signed in 441, two years later Constantinople again failed to deliver the tribute and war resumed. In the following campaign, Hun armies came alarmingly close to Constantinople, sacking Sardica, Arcadiopolis and Philippopolis along the way. Suffering a complete defeat at the Battle of Chersonesus, the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II gave in to Hun demands and in autumn 443 signed the Peace of Anatolius with the two Hun kings. The Huns returned to their lands with a vast train full of plunder.

Unified Empire under Attila

Hunnic Empire | |

|---|---|

| 370s–469 | |

The Hunnic Empire under Attila | |

| Common languages | Hunnic Gothic Various tribal languages |

| Government | Tribal Confederation |

| High King | |

• 370s | Balamber |

• c. 435–445 | Attila and Bleda |

• 445–453 | Attila |

• 453–469 | Dengizich |

| History | |

• Huns appear north-west of the Caspian Sea | pre 370s |

• Balamber began uniting the Huns and Germanic tribes | 370s |

| 437 | |

• Death of Bleda, Attila becomes sole ruler | 445 |

| 451 | |

• Invasion of northern Italy | 452 |

| 454 | |

• Dengizich, son of Attila, dies | 469 |

| Today part of | |

Bleda died in 445, with some historians speculating that his death was at the hands of Attila. With his brother gone, Attila was able to establish undisputed control over his subjects. In 447, Attila turned the Huns back toward the Eastern Roman Empire once more. His invasion of the Balkans and Thrace was devastating. The Eastern Roman Empire was already beset by internal problems, such as famine and plague, as well as riots and a series of earthquakes in Constantinople itself. A last-minute rebuilding of its walls preserved Constantinople unscathed. Victory over a Roman army left the Huns virtually unchallenged in Eastern Roman lands and they raided as far south as Thermopylae. Only disease forced them to retreat, and the war came to an end in 449 with an agreement in which the Romans agreed to pay Attila an annual tribute of 2100 pounds of gold. Our only first-hand account of conditions among the Huns and of Attila himself is by Priscus, an official in the peace embassy to Attila.

Throughout their raids on the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns had maintained good relations with the Western Empire, and in particular with Flavius Aetius, a powerful Roman general (sometimes even referred to as the de facto ruler of the Western Empire) who in his youth had spent time as a hostage with the Huns. However, this all changed in 450 when Honoria, sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and requested his help to escape her betrothal to a senator. Attila claimed her as his bride and half the Western Roman Empire as dowry.[56] Additionally, a dispute arose between Attila and Aetius about the rightful heir to a king of the Salian Franks. Finally, Attila's ability to distribute treasure to favoured followers was an important support to his power, and the repeated extortion from the Eastern Roman Empire had left it with little to plunder.

In 451, Attila's forces entered Gaul, accumulating contingents from the Franks, Goths and Burgundian tribes en route. Once in Gaul, the Huns first attacked Metz, then his armies continued westwards, passing both Paris and Troyes to lay siege to Orléans.

Aetius was given the duty of relieving Orléans by Emperor Valentinian III. Bolstered by Frankish and Visigothic troops (under King Theodoric), Aetius' own Roman army met the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. Although a tactical defeat for Attila, thwarting his invasion of Gaul and forcing his retreat back to non-Roman lands, the macrohistorical significance of the allied and Roman victory is a matter of debate.[57][58][59]

The following year, Attila renewed his claims to Honoria and territory in the Western Roman Empire. Leading his horde across the Alps and into Northern Italy, he sacked and razed the cities of Aquileia, Vicetia, Verona, Brixia, Bergamum and Milan. Hoping to avoid the sack of Rome, Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, the high civilian officers Gennadius Avienus and Trigetius, as well as Pope Leo I, who met Attila at Mincio in the vicinity of Mantua, and obtained from him the promise that he would withdraw from Italy and negotiate peace with the emperor. Prosper of Aquitaine describes the historic meeting, giving all the credit of the successful negotiation to Leo. Priscus reports that superstitious fear of the fate of Alaric—who died shortly after sacking Rome in 410—gave him pause. More practically, Italy had suffered from a terrible famine in 451 and her crops were faring little better in 452; Attila's invasion of the plains of Northern Italy this year did not improve the harvest. To advance on Rome would have required supplies which were not available in Italy, and taking the city would not have improved Attila's supply situation. Secondly, an East Roman force had crossed the Danube and defeated the Huns who had been left behind by Attila to safeguard their home territories. Attila, hence, faced heavy human and natural pressures to retire from Italy before moving south of the Po. Attila retreated without Honoria or her dowry.[60]

The new Eastern Roman Emperor Marcian then halted tribute payments. From the Pannonian Basin, Attila planned to attack Constantinople. However, in 453 he married a girl with the Germanic name Ildico, and died of a haemorrhage on his wedding night.[61]

After Attila

After Attila's death in 453, the Hunnic Empire faced an internal power struggle between its vassalized Germanic peoples and the Hunnic ruling body. Led by Ellak, Attila's favored son and ruler of the Akatziri, the Huns engaged the Gepid king Ardaric at the Battle of Nedao, who led a coalition of Germanic Peoples to overthrow Hunnic imperial authority. The Amali Goths would revolt the same year under Valamir, allegedly defeating the Huns in a separate engagement.[62] However, this did not result in the complete collapse of Hunnic power in the Carpathian region, but did result in the loss of many of their Germanic vassals. At the same time, the Huns were also dealing with the arrival of more Oghur Turkic speaking peoples from the East, including the Oghurs, Saragurs, Onogurs, and the Sabirs. In 463, the Saragurs defeated the Akatziri, or Akatir Huns, and asserted dominance in the Pontic region.[63]

In 458 some Huns served under Tudila in Majorian's army, probably belonging to a group settled under Emnetzur and Ultzindur in Dacia Ripesnsis.[64] The western Huns under Dengzich were experiencing difficulties in 461, when they were defeated by Valamir in a war against the Sadages, a people allied with the Huns.[65] His campaigning was also met with dissatisfaction from Ernak, ruler of the Akatziri Huns, who wanted to focus on the incoming Oghur speaking peoples.[63] In 465–466, Ernak and Dengzich sent ambassadors to Constantinople requesting a peace treaty, and asking to establish a market for the exchange of needed provisions. However these requests were rejected, and Dengzich attacked the Romans in 467, without the assistance of Ernak. He was surrounded by the Romans and besieged, and came to an agreement that they would surrender if they were given land and his starving forces given food. During the negotiations, a Hun in service of the Romans named Chelchel persuaded the enemy Goths to attack their Hun overlords. The Romans, under their General Aspar and with the help of his bucellarii, then attacked the quarreling Goths and Huns, defeating them.[66]

In 469, Anagastes, the son of Arnegisclus who was slain by Attila, brought Dengzich's head and paraded it through the streets before mounting it on a stake in the Hippodrome.[67] Some Historians, like John Man, accept this date as the end of the Hunnic Empire.[68] However others, such as Kim, argue it continued under Ernak who absorbed the incoming Oghur speakers. These people were similar to the Huns and Attila's empire continued as the Kutrigur and Utigur Hunno-Bulgars.[63] This conclusion is still subject to some controversy.

Society and culture

Appearance

As the Huns were illiterate and thus kept no records, all surviving accounts were written by enemies of the Huns, and none describe the Huns as attractive either morally or in appearance. Jordanes, a Goth writing in Italy in 551, a century after the collapse of the Hunnic Empire, describes the Huns as a "savage race, which dwelt at first in the swamps, a stunted, foul and puny tribe, scarcely human and having no language save one which bore but slight resemblance to human speech."[69]: 122 Jordanes goes on to write:

They made their foes flee in horror because their swarthy aspect was fearful, and they had, if I may call it so, a sort of shapeless lump, not a head, with pin-holes rather than eyes. Their hardihood is evident in their wild appearance, and they are beings who are cruel to their children on the very day they are born. For they cut the cheeks of the males with a sword, so that before they receive the nourishment of milk they must learn to endure wounds. Hence they grow old beardless and their young men are without comeliness, because a face furrowed by the sword spoils by its scars the natural beauty of a beard. They are short in stature, quick in bodily movement, alert horsemen, broad shouldered, ready in the use of bow and arrow, and have firm-set necks which are ever erect in pride. Though they live in the form of men, they have the cruelty of wild beasts.[69]: 127–8

Jordanes also recounted how Priscus had described Attila the Hun, the Emperor of the Huns from 434–453, as: "Short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his eyes were small, his beard thin and sprinkled with grey; and he had a flat nose and tanned skin, showing evidence of his origin."[70]: 182

In forming their view of Attila's people, the Romans tapped into attitudes inherited from the Greeks. These were the vilest creatures imaginable. They came from the North and everyone knew that the colder the climate was, the more barbaric the people were.[71] They knew nothing of metal, had no religion and lived like savages, without fire, eating their food raw, living off roots, and meat tenderized by placing it under their horses' saddles. They had no buildings, of course, not so much as a reed hut, indeed, they feared the very idea of venturing under a roof.[71]

The description of Huns given by the Romans has prompted some historians to believe they were of East Asian origin. Denis Sinor, noting the paucity of anthropological evidence, wrote that "there is no reason to question the basic accuracy of the western descriptions, and the absence of massive supporting evidence by physical anthropology cannot weaken the point they so tellingly make. It is the unusual that most attracts attention."[1] However, Austrian traveler Maenchen-Helfen wrote in the 20th century:

Ammianus' description begins with a strange misunderstanding ... This was repeated by Claudian and Sidonius and reinterpreted by Cassiodorus. Ammianus' explanation of the thin beards is wrong. Like so many other people, the Huns inflicted wounds on their live flesh as a sign of grief when their kinsmen were dying.[72]

Artificial cranial deformation

Artificial cranial deformation was practiced by the Huns and sometimes by tribes under their influence.[74][75][76][77] Artificial cranial deformation of the circular type can be used to trace the route that the Huns took from north China to the Central Asian steppes and subsequently to the southern Russian steppes.[78] The people who practiced annular type artificial cranial deformation in Central Asia were Yuezhi/Kushans.[79][80][81]

Some artificially deformed crania from the 5th–6th Century AD have been found in Northeastern Hungary and elsewhere in Western Europe. None of them have any Mongoloid features and all the skulls appear Europoid; these skulls may have belonged to Germanic or other subject groups whose parents wished to elevate their status by following a custom introduced by the Huns.[35]

Government

Hunnic governmental structure has long been debated. In the past many scholars argued that the Huns did not have a central organization until after they entered Europe. Peter Heather argued the Huns were a disorganized confederation in which leaders acted completely independently and that eventually established a ranking heirarchy, much like Germanic societies.[82] However this has been challenged in recent years. According to Kim, it is now believed that the Huns continued the Xiongnu organization, in which their polity was divided into Left, Right, South, and North, in that order of priority.[83] It is also thought that the Huns continued the council of "six horns/nobles" that the Xiongnu had under their emperor.[84] It is unknown what the Hun emperor was called, but the terms Chanyu, Aniliki, Shah, and Yabgu are possible or interchangeable titles for the same position, as they were in use by other contemporary peoples during that period.[85] Likewise, it is suggested that that the Huns continued to use the decimal military organization of the Xiongnu as well.[86]

Language

A variety of languages were spoken within the Hun Empire.[87] It has been supposed that by the 440s, the "Huns" were more Germanic-speaking subject than speakers of Hunnic, and as such Gothic may have been a lingua franca of the Empire.[88][89] Kim however points out that there is no evidence for the idea that Gothic was a lingua franca.[90] Subjects of the Huns also included Iranian-speaking Alans and Sarmatians.[37] Based on some etymological interpretation of the words strava, medos, and kamos and subsequent historical appearance, the other languages have been taken to include a form of Proto-Slavic language.[91][92][93]

Priscus noted that the Hunnic language differed from other languages spoken at Attila's court.[94] He recounts how Zerco made Attila's guests laugh also by the "promiscuous jumble of words, Latin mixed with Hunnish and Gothic".[94] Priscus said that Attila's "Scythian" subjects spoke "besides their own barbarian tongues, either Hunnish, or Gothic, or, as many have dealings with the Western Romans, Latin; but not one of them easily speaks Greek, except captives from the Thracian or Illyrian frontier regions".[95]

The ancient sources are thus clear that there was a Hunnic language. The literary sources preserve many names, and three Indo-European words (medos, kamos, strava), which have been studied for more than a century and a half.[96] Otto Maenchen-Helfen noted that the thesis suggesting the Huns spoke a Turkic language has a long history behind it.[97] Maenchen-Helfen held that by Turkic origin of Hunnic tribal and proper names, the Huns spoke a Turkic language.[98] Denis Sinor argued that "at least part of the Hun leadership was Turkic-speaking".[1]

Traditionally notable studies of proper names chronologically include that of Gyula Németh, Gerhard Doerfer, Maenchen-Helfen, and Omeljan Pritsak.[1] In Pritsak's 1982 study The Hunnic Language of the Attila Clan,[99] he analyzes the 33 survived personal names and concludes:

It was not a Turkic language, but one between Turkic and Mongolian, probably closer to the former than the latter. The language had strong ties to Bulgar language and to modern Chuvash, but also had some important connections, especially lexical and morphological, to Ottoman Turkish and Yakut.[99]

On the basis of the existing name records, a number of scholars suggest that the Huns spoke a Turkic language of the Oghur branch, which also includes the Bulgar, Khazar and Chuvash languages.[100][101][102] Peter Heather called the Huns "the first group of Turkic, as opposed to Iranian, nomads to have intruded into Europe".[103] Many recent scholars agree that Hunnic was related to Turkic and Mongolian languages.[104]

In 2013, Hyun Jin Kim suggested that "from the names that we do know, most of which seem to be Turkic... the Hunnic elite was predominantly Turkic-speaking."[90] He also suggests that the Xiongnu, who had originally spoken Yeniseian, flipped to Oghur Turkic when they absorbed the Dingling and crossed into Central Asia, like the later Golden Horde and Chagatai Khanate.[105] He noted that, beside Hunnic, people in Attila's court also spoke Gothic and Latin, and that in the western part of the Empire, where subjected Goths lived, people described as Huns probably spoke both the Hunnic and Gothic languages. An example would be the Germanic or Germanized names of noted Huns like Laudaricus.[90]

Nevertheless, some scholars still conclude that the Hunnic language cannot presently be classified, and attempts to classify it as Turkic or Mongolic are speculative.[106][107][108]

Warfare

Strategy and tactics

Hun warfare as a whole is not well studied, and many scholars as of recent have discounted Ammianus' description of the Huns.[109] This was first pointed out by E.A. Thompson, who stated that the Huns could never have conquered Europe without iron armor and weapons.[110] The only accurate information on Hun warfare comes from the 6th-century Strategikon, which describes the warfare of "Dealing with the Scythians, that is, Avars, Turks, and others whose way of life resembles that of the Hunnish peoples." The Strategikon describes the Avars and Huns as devious and very experienced in military matters.[111] They are described as preferring to defeat their enemies by deceit, surprise attacks, and cutting off supplies. The Huns brought large numbers of horses to use as replacements and to give the impression of a larger army on campaign.[111] The Hunnish peoples did not set up an entrenched camp, but spread out across the grazing fields according to clan, and guard their necessary horses until they began forming the battle line under the cover of early morning. The Strategikon states the Huns also stationed sentries at significant distances and in constant contact with each other in order to prevent surprise attacks.[112]

According to the Strategikon, the Huns did not form a battle line in the method that the Romans and Persians used, but in irregularly sized divisions in a single line, and keep a separate force in reserve for ambushes and as a reserve. The Strategikon also states the Huns used deep formations with a dense and even front.[112] Otto Maenchen-Helfen states that the Huns likely formed up in divisions according to tribal clans and families which Ammianus calls Cunei, the leader of which was called a Cur and inherited the title as it was passed down through the clan.[113] The Strategikon states that the Huns kept their spare horses and baggage train to either side of the line about a mile away, with a moderate sized guard, and would sometimes tie their spare horses together behind the main battle line.[112] The Huns preferred to fight at long range, utilizing ambush, encirclement, and the feigned retreat. The Strategikon also makes note of the wedge shaped formations mentioned by Ammianus, and corroborated as familial regiments by Maenchen-Helfen.[112][113][114] The Strategikon states the Huns preferred to pursue their enemies relentlessly after a victory and then wear them out by a long siege after defeat.[112]

Military equipment

The Strategikon states the Huns typically used maille, swords, bows, and lances, and that most Hunnic warriors were armed with both the bow and lance and used them interchangeably as needed. It also states the Huns used quilted linen, wool, or sometimes iron barding for their horses and also wore quilted coifs and kaftans.[115] This assessment is largely corroborated by archaeological finds of Hun military equipment, such as the Volnikovka and Brut Burials.

A late Roman ridge helmet of the Berkasovo-Type was found with a Hun burial at Concesti.[116] A Hunnic helmet of the Segmentehelm type was found at Chudjasky, and another of the Bandhelm type at Turaevo.[117] Fragments of lamellar helmets dating to the Hunnic period and within the Hunnic sphere have been found at Iatrus, Illichevka, and Kalkhni.[116][117] Hun lamellar armour has not been found in Europe, although two fragments of likely Hun origin have been found on the Upper Ob and in West Kazakhstan dating to the 3rd–4th centuries.[citation needed] An unpublished find at a military warehouse near Toprachioi, Romania is known but it is uncertain if it can be attributed to Hun origin. It is known that the Eurasian Avars introduced Lamellar armor to the Roman Army and Migration Era Germanics in the Middle 6th Century, but this later type does not appear before then.[116][118]

It is also widely accepted that the Huns introduced the langseax, a 60 cm cutting blade that became popular among the migration era Germanics and in the Late Roman Army, into Europe.[119] It is believed these blades originated in China and that the Sarmatians and Huns served as a transmission vector, using shorter seaxes in Central Asia that developed into the narrow langseax in Eastern Europe during the late 4th and first half of the 5th century. These earlier blades date as far back as the 1st century AD, with the first of the newer type appearing in Eastern Europe being the Wien-Simmerming example, dated to the late 4th century AD.[119] Other notable Hun examples include the Langseax from the more recent find at Volnikovka in Russia.[120]

The Huns used a type of spatha in the Iranic or Sassanid style, with a long, straight approximately 83cm blade, usually with a diamond shaped iron guard plate.[121] Swords of this style have been found at sites such as Altlussheim, Szirmabesenyo, Volnikovka, Novo-Ivanovka, and Tsibilium 61. They typically had gold foil hilts, gold sheet scabbards, and scabbard fittings decorated in the polychrome style. The sword was carried in the "Iranian style" attached to a swordbelt, rather than on a baldric.[122]

The most famous weapon of the Huns, of course, is the Qum Darya-type composite recurve bow, often called the "Hunnish Bow." This bow was invented some time in the 3rd or 2nd centuries BC with the earliest finds near Lake Baikal, but spread across Eurasia long before the Hunnic migration. These bows were typified by being asymmetric in cross-section between 145-155cm in length, having between 4–9 lathes on the grip and in the siyahs.[123] Although whole bows rarely survive in European climatic conditions, finds of bone Siyahs are quite common and characteristic of steppe burials. Complete specimens have been found at sites in the Tarim Basin and Gobi Desert such as Niya, Qum Darya, and Shombuuziin-Belchir. Eurasian nomads such as the Huns typically used trilobate diamond shaped iron arrowheads, attached using birch tar and a tang, with typically 75cm shafts and fletching attached with tar and sinew whipping. Such trilobate arrowheads are believed to be more accurate and have better penetrating power or capacity to injure than flat arrowheads.[123]

Legacy

Legends

Chroniclers writing centuries later often mentioned or alluded to Huns or their purported descendants. These include:

- Theophylact Simocatta

- Annales Fuldenses

- Annales Alamannici

- Annals of Salzburg

- Liutprand of Cremona's Antapodosis

- Regino of Prüm's chronicle

- Widukind of Corvey's Saxon Chronicle

- Nestor the Chronicler's Primary Chronicle

- Legends of Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Aventinus's Chronicon Bavaria

- Constantine VII's De Administrando Imperio

- Leo VI the Wise's Tactica

Medieval Hungarians continued this tradition (see Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum, Chronicon Pictum, Gesta Hungarorum).

Memory of the Hunnic conquest was transmitted orally among Germanic peoples and is an important component in the Old Norse Völsunga saga and Hervarar saga and in the Middle High German Nibelungenlied. These stories all portray Migration Period events from a millennium earlier.

In the Hervarar saga, the Goths make first contact with the bow-wielding Huns and meet them in an epic battle on the plains of the Danube.

In the Nibelungenlied, Kriemhild marries Attila (Etzel in German) after her first husband Siegfried was murdered by Hagen with the complicity of her brother, King Gunther. She then uses her power as Etzel's wife to take a bloody revenge in which not only Hagen and Gunther but all Burgundian knights find their death at festivities to which she and Etzel had invited them.

In the Völsunga saga, Attila (Atli in Norse) defeats the Frankish king Sigebert I (Sigurðr or Siegfried) and the Burgundian King Guntram (Gunnar or Gunther), but is later assassinated by Queen Fredegund (Gudrun or Kriemhild), the sister of the latter and wife of the former.

In the German "Saga of Tidreck of Bern", its written versions beginning from the 13th century, the Huns are called Frisians. Frisia was often called Hunaland in the Middle Ages.[124][125]

Widsith, possibly one of the oldest pieces of English literature to survive to the present day, lists a number of ancient kings of tribes sorted according to their popularity and impact; Attila, King of the Huns, comes first, followed immediately by Eormanric of the Ostrogoths.[126]: 187 Widsith may be by far the oldest extant work that tells of the Battle of the Goths and Huns, also recounted in later Scandinavian works such as the Hervarar saga;[126]: 179 in Widsith, however, the battle's details are presented as "sober historical facts" rather than as the "heroic stories" of later works.[126]: 184 The name Attila, rendered in Old English as Ætla,[note 1] was a given name in use in Anglo-Saxon England (ex. Bishop Ætla of Dorchester) and its use in England at the time may have been connected to the heroic kings legend represented in works like Widsith,[127] though historian Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen doubts the use of the name by the Anglo-Saxons had anything to do with the Huns, and argues it was more likely to be based directly on the name's Germanic origin meaning "little father".[128]

Claims of Hunnic origins

The Hungarians (Magyars) in particular lay claim to Hunnic heritage. Although Magyar tribes only began to settle in the geographical area of present-day Hungary in the very end of the 9th century, some 426 years after the breakup of Attila's Hunnic Empire, Hungarian prehistory includes Magyar origin myths. There is also a medieval legend of a lineage that makes Attila the sixth-generation ancestor of Árpád conqueror of the modern Pannonian basin, through Attila's son Csaba, his son Ed, his son Ügyek, his son Előd, his son Álmos. Álmos was ruler of the Magyars and the father of Arpad[129] The national anthem of Hungary describes the Hungarians as "blood of Bendegúz'" (the medieval and modern Hungarian version of Mundzuk, Attila's father). Attila's brother, Bleda, is called Buda in modern Hungarian and some medieval chronicles and literary works attribute the name of the city of Buda to him.

There is a legend among the Székely people that claims that after the death of Attila, in a battle called the Battle of Krimhilda, 3000 Hun warriors managed to escape and settle in a place called "Csigle-mező" (today Transylvania) and they changed their name from Huns to Szekler (Székely). According to the Hungarian scholar Egyed, the Székelys speak the Hungarian language "without any trace of a Turkic substratum", indicating that they did not have a language shift during their history, and proposes that the Székelys were descended from privileged Hungarian groups.[130][131] They therefore could not have been related to the Huns, who most likely spoke an Oghur Turkic dialect.

The Anglo-Saxons may have believed themselves to be partly descended from Huns, through their Angle, Saxon, and Jute ancestors.[127] In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the historian Bede stated:

... [M]any of which nations [Egbert] knew there were in Germany, from whom the Angles or Saxons, who now inhabit Britain, are known to have derived their origin; for which reason they are still corruptly called Garmans by the neighboring nation of the Britons. Such are the Frisons, the Rugins, the Danes, the Huns, the Ancient Saxons, and the Boructuars (or Bructers). There are also in the same parts many other nations still following pagan rites, to whom the aforesaid soldier of Christ designed to repair, ...[132]

As James Campbell has noted, this list of peoples has generally been regarded by historians as being a list of peoples living in Germany at the time Bede wrote this passage in the 8th century, "[b]ut the sense of the Latin is that these are the peoples from whom the Anglo-Saxons living in Britain were derived."[133]: 53 He wrote that the list of peoples fits the 5th century better, when the Anglo-Saxons began migrating to Britain, than the 8th century, and noted that "Huns sound odd; it is equally odd that Priscus heard of a boast by Attila that he had authority over the islands in the ocean."[133]: 124

20th-century use in reference to Germans

On 27 July 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion in China, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany gave the order to act ruthlessly towards the rebels: "Mercy will not be shown, prisoners will not be taken. Just as a thousand years ago, the Huns under Attila won a reputation of might that lives on in legends, so may the name of Germany in China, such that no Chinese will even again dare so much as to look askance at a German."[134]

The term "Hun" from this speech was later used for the Germans by British propaganda during World War I. The comparison was helped by the spiked Pickelhaube helmet worn by German forces until 1916, which would be reminiscent of images depicting ancient Hun helmets. This usage, emphasising the idea that the Germans were barbarians, was reinforced by Allied propaganda throughout the war. The French songwriter Theodore Botrel described the Kaiser as "an Attila, without remorse", launching "cannibal hordes".[135]

The usage of the term "Hun" to describe Germans resurfaced during World War II. For example, Winston Churchill 1941 said in a broadcast speech: "There are less than 70,000,000 malignant Huns, some of whom are curable and others killable, most of whom are already engaged in holding down Austrians, Czechs, Poles and the many other ancient races they now bully and pillage."[136] Later that year Churchill referred to the invasion of the Soviet Union as "the dull, drilled, docile brutish masses of the Hun soldiery, plodding on like a swarm of crawling locusts."[137] During this time American President Franklin D. Roosevelt also referred to the German people in this way, saying that an Allied invasion into Southern France would surely "be successful and of great assistance to Eisenhower in driving the Huns from France."[138]

Sectarian slur in Northern Ireland and Scotland

"Hun" is also used as an sectarian slur against Protestants in Scotland and Northern Ireland.[139] In Scotland, the term has been used by fans of Celtic FC in Old Firm derbies against Rangers FC supporters,[140] while Orange Halls in Ulster have been daubed with graffiti reading KAH ("Kill all Huns").[141]

A pamphlet issued to PSNI officers in 2008 listed "Huns" – along with the terms "black", "prods" or "jaffas" (referring to the Orange Order) for Protestants and "fenians", "taigs", "chucks" or "spongers" for Irish Catholics – as terms not to use to avoid causing offence.[142]

See also

Notes

- ^ The Æ/æ in Ætla is pronounced like the 'a' in 'cat' in most Modern English dialects; it is the near-open front unrounded vowel. (See also Old English phonology.)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sinor (editor), Denis (1990). The Cambridge history of early Inner Asia (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 177–203. ISBN 9780521243049.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ de Guignes, Joseph (1756–1758). Histoire générale des Huns, des Turcs, des Mongols et des autres Tartares (in French).

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 228.

- ^ "However, the seed and origin of all the ruin and various disasters that the wrath of Mars aroused ... we have found to be (the invasions of the Huns)". Ammianus 1922, XXXI, ch. 2

- ^ Pohl 1999, pp. 501–502.

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 502.

- ^ de la Vaissière 2015, p. 176.

- ^ Pohl 1999, p. 502.

- ^ a b Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (31.2.), p. 411.

- ^ a b de la Vaissière 2015, p. 177.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 4. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 2–4. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ The Gothic History of Jordanes (24:121), p. 85.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 5. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 209.

- ^ British Museum notice

- ^ Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History, and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity, Anthony Kaldellis, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012, p.70

- ^ Staying Roman: Conquest and Identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439–700, Jonathan Conant Cambridge University Press, 2012 p.259

- ^ Procopius, History of the Wars. Book I, Ch. III, "The Persian War"

- ^ de la Vaissière 2015, p. 175, 180.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 38, 55, 72–79. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Wright, David Curtis (2011). The history of China (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara: Greenwood. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-313-37748-8.

- ^ de la Vaissière 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Wright 2011, p. 60. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWright2011 (help)

- ^ a b de la Vaissière 2015, p. 179.

- ^ de la Vaissière 2015, p. 181.

- ^ Atwood 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Atwood 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Zhengzhang 2003, p. 429,505.

- ^ a b de la Vaissière 2015, p. 188.

- ^ THE PEOPLES OF THE STEPPE FRONTIER IN EARLY CHINESE SOURCES, Edwin G. Pulleyblank, page 37

- ^ de la Vaissière 2015, p. 187.

- ^ Hayashi 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1945.

- ^ a b c Molnár, Mónika; János, István; Szűcs, László; Szathmáry, László (April 2014). "Artificially deformed crania from the Hun-Germanic Period (5th–6th century AD) in northeastern Hungary: historical and morphological analysis". Journal of Neurosurgery. American Association of Neurological Surgeons. p. E1. doi:10.3171/2014.1.FOCUS13466. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Kim 2013, p. 33, 39. sfn error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFKim2013 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Heather, Peter (2005). The fall of the Roman Empire : a new history of Rome and the barbarians. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 146–167. ISBN 978-0-19-515954-7.

- ^ a b Kim 2013, p. 31. sfn error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFKim2013 (help)

- ^ a b Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 447. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ a b c Thompson 2001, p. 25.

- ^ a b Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 449. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 452–453. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Thompson 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Heather 2010, p. 215.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 19. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Heather 2010, p. 212.

- ^ Heather 2010, pp. 212–217.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (31.3.), p. 415.

- ^ a b c d Thompson 2001, p. 27.

- ^ a b Thompson 2001, p. 28.

- ^ a b James 2009, p. 51.

- ^ a b Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 26. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ a b c Thompson, E. A. 1948. A History of Attila and the Huns. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Thompson, E. A.; et al. (1999). The Huns. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 136.

- ^ Harvey, Bonnie (2003). Attila the Hun. Infobase Publishing. p. 15.

- ^ Halsall 2007, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Creasy, Edward Shepherd: The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World.

- ^ Norwich, Byzantium: the Early Centuries. 1997, p. 158.

- ^ Bury, The Later Roman Empire, pp. 294f.

- ^ Halsall 2007, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 364. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Heather, Peter (1996). The Goths. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 124.

- ^ a b c Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 132.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1973). On the World of the Huns. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 151, 161–162.

- ^ Heather, Peter (1996). The Goths. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 125.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1973). On the World of the Huns. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 165–168.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1973). On the World of the Huns. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 168.

- ^ Man, John (2005). Attila: The Barbarian who Challenged Rome. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 278.

- ^ a b "Who was Who in Roman Times: The Goths by Jordanes". Retrieved 4 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Who was Who in Roman Times :The Goths by Jordanes". Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ a b Attila The Hun, by John Man, Bantam Books, 2005, p.79

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 361. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas p.286

- ^ Delius, Peter (2005). Visual History of the World. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-3695-5.

- ^ "Schädelrekonstruktion und Atelierfoto" (in German). Speyer: Museum der Pfalz. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S., A history of the Alans in the West: from their first appearance in the sources of classical antiquity through the early Middle Ages, U of Minnesota Press (1973), pp. 67–69

- ^ Pany, Doris; Wiltschke-Schrotta, Karin. "Artificial cranial deformation in a migration period burial of Schwarzenbach, Lower Austria" (PDF). VIAVIAS, no. 2 (Vienna Institute for Archaeological Science 2008), pp. 18–23.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Torres-Rouff, C.; Yablonsky, L.T. "Cranial vault modification as a cultural artifact". HOMO – Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 56 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2004.09.001.

- ^ "The Kushan civilization", Buddha Rashmi Mani, page 5: "A particular intra-cranial investigation relates to an annular artificial head deformation (macrocephalic), evident on the skulls of diverse racial groups being a characteristic feature traceable on several figures of Kushan kings on coins.", https://books.google.bg/books?id=J_YtAAAAMAAJ&q=kushan+deformation&dq=kushan+deformation&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y

- ^ Kim 2013, p. 33. sfn error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFKim2013 (help)

- ^ Hansen, Bent. "An original Danevang could have been situated in Central Asia". Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Heather, Peter, “Huns and the End of the Roman Empire in Western Europe” in English Historical Review (1995): 11;

- ^ Kim, The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe, 23, 207

- ^ Kim, The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe, 58-59, 208

- ^ Atwood, Huns and Xiongnu – New Thoughts on an Old Problem, 33; Kim, The Huns, Rome, and the Birth Of Europe, 31, 59, 206

- ^ Kim, The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe, 59

- ^ Blockley, RC 1983. The Fragmentary Classicising Historians of the Later Roman Empire. Liverpool: Francis Cairns; citing Priscus

- ^ Wolfram 1990, p. 254.

- ^ Wolfram 1997, p. 142.

- ^ a b c Kim 2013, p. 30. sfn error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFKim2013 (help)

- ^ Walter Pohl. 1999. Huns. Late Antiquity: a guide to the postclassical world, ed. Glen Warren Bowersock, Peter Robert Lamont Brown, Oleg Grabar. Harvard University Press. pp. 501–502

- ^ Schenker, Alexander. 1995. The Dawn of Slavic: an introduction to Slavic philology. Yale University Press.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 424–426. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ a b Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 377. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 382. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 376, 424–426. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 403. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 441. sfn error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFMaenchen-Helfen1973 (help)

- ^ a b Pritsak, Omeljan (1982). The Hunnic Language of the Attila Clan (PDF). Vol. IV. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. ISSN 0363-5570.

- ^ Johanson, Lars; Éva Agnes Csató (ed.). 1998. The Turkic languages. Routledge.

- ^ "It is assumed that the Huns also were speakers of an l- and r- type Turkic language and that their migration was responsible for the appearance of this language in the West." Johanson (1998); cf. Johanson (2000, 2007) and the articles pertaining to the subject in Johanson & Csató (ed., 1998).

- ^ Victor H. Mair, Contact And Exchange in the Ancient World, 2006, University of Hawaii Press, p.136

- ^ Heather, Peter. 1995. The Huns and the End of the Roman Empire in Western Europe. English Historical Review, 90: 4-41.

- ^ Marácz, Lászlo (2009). "Borbála Obrusánszky: Heritage of the Huns" (PDF). Journal of Eurasian Studies. 1: 158.

- ^ Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 29.

- ^ Template:De icon Doerfer, Gerhard. Zur Sprache der Hunnen. Central Asiatic Journal, 17(1): 1-50.

- ^ Sinor, Denis. 1977. The Outlines of Hungarian Prehistory. Journal of World History, 4(3):513–540.

- ^ Poppe, Nicholas. 1965. Introduction to Altaic linguistics. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. Ural-altaische Bibliothek; 14.

- ^ Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–19.

- ^ Thompson, Edward Arthur (1948). A History of Attila and the Huns. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press. pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b Dennis, George T. (1984). Maurice's Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e Dennis, George T. (1984). Maurice's Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 117.

- ^ a b Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1973). On the World of the Huns. Los Angelas: University of California Press. pp. 202–203.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 31.2.8

- ^ Dennis, George T. (1984). Maurice's Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 11–13 and 116.

- ^ a b c Glad, Damien (2010). "The Empire's Influence on Barbarian Elites from the Pontus to the Rhine (5th–7th Centuries): A Case Study of Lamellar Weapons and Segmental Helmets". The Pontic-Danubian Realm in the Period of the Great Migration. Paris: Arheološki Institut Beograd: 349–362.

- ^ a b Miks, Christian (2009). "RELIKTE EINES FRÜHMITTELALTERLICHEN OBERSCHICHTGRABES? Überlegungen zu einem Konvolut bemerkenswerter Objekte aus dem Kunsthandel". JAHRBUCH DES RÖMISCH-GERMANISCHEN ZENTRALMUSEUMS MAINZ. 56: 500.

- ^ Burgarski, Ivan (2005). "A Contribution to the Study of Lamellar Armours". Starinar. 55: 161–179.

- ^ a b Kiss, Attila P. (2014). "Huns, Germans, Byzantines? The Origins of the Narrow Bladed Long Seaxes". Acta Archaeologica Carpathia. 49: 131–164.

- ^ Radjush, Oleg; Scheglova, Olga (2014). The Buried Treasure of Volnikovka: Horse and Rider Outfit Complex. First Half of the V Century AD. Collection Catalogue. p. 31.

- ^ James, Simon (2011). Rome and the Sword. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 266.

- ^ Kazanski, Michel (2013). "Barbarian Military Equipment and its Evolution in the Late Roman and Great Migration Periods (3rd–5th C. A.D.)". Ware and Warfare in Late Antiquity. 8.1: 493–522.

- ^ a b Reisinger, Michaela R. (2010). "New Evidence About Composite Bows and Their Arrows in Inner Asia". The Silk Road. 8: 42–62.

- ^ Veselovsky. Russians and veltinas in the Saga of Tidreck of Bern (Verona). Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 1906 in Russian Веселовский "Русские и вильтины в саге о Тидреке Бернском (Веронском)" (СПб., 1906)

- ^ "НОРМАНСКАЯ КОНЦЕПЦИЯ И ЕЕ КРИТИКА – rusfact.ru". Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ a b c Lotte, Hedeager, (2011). "Knowledge production reconsidered". Iron Age myth and materiality : an archaeology of Scandinavia, AD 400–1000. Abingdon, Oxfordshire; New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 177–190. ISBN 9780415606042. OCLC 666403125.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Neidorf, Leonard (2013-01-01). "The Dating of Widsið and the Study of Germanic Antiquity". Neophilologus. 97 (1): 165–183. doi:10.1007/s11061-012-9308-2. ISSN 0028-2677.

- ^ Otto., Maenchen-Helfen, (1973). "Chapter IX". The world of the Huns : studies in their history and culture. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520015968.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum (in Latin)

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help). - ^ Engel 2001, p. 116.

- ^ Egyed 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Jane, Lionel (1911). [[s:Ecclesiastical History of the English People|Ecclesiastical History of the English People]] – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ a b 1935–2016, Campbell, James, (1986). Essays in Anglo-Saxon history. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 090762832X. OCLC 458534293.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weser-Zeitung, 28 July 1900, second morning edition, p. 1: 'Wie vor tausend Jahren die Hunnen unter ihrem König Etzel sich einen Namen gemacht, der sie noch jetzt in der Überlieferung gewaltig erscheinen läßt, so möge der Name Deutschland in China in einer solchen Weise bekannt werden, daß niemals wieder ein Chinese es wagt, etwa einen Deutschen auch nur schiel anzusehen'.

- ^ "Quand un Attila, sans remords, / Lance ses hordes cannibales, / Tout est bon qui meurtrit et mord: / Les chansons, aussi, sont des balles!", from Theodore Botrel, by Edgar Preston T.P.'s Journal of Great Deeds of the Great War, February 27, 1915

- ^ "PRIME MINISTER WINSTON CHURCHILL'S BROADCAST "REPORT ON THE WAR"".

- ^ Churchill, Winston S. 1941. "WINSTON CHURCHILL'S BROADCAST ON THE SOVIET-GERMAN WAR", London, June 22, 1941

- ^ Winston Churchill. 1953. "Triumph and Tragedy" (volume 6 of The Second World War). Boston: Houghton-Mifflin. Ch. 4, p. 70

- ^ "What does the word 'hun' mean and what is its place in today's society?". Irish Post. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ Cooney, Darren. "Rangers fans group Club 1872 wants Celtic supporters banned from Ibrox". Daily Record. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "'Kill all huns' painted on small Orange hall". Belfast News Letter. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "Police outlaw 'fenians and huns'". BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

Sources

Primary sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus: The Later Roman Empire (AD 354–378) (Selected and translated by Walter Hamilton, With an Introduction and Notes by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill) (2004). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044406-3.

- The Gothic History of Jordanes (in English Version with an Introduction and a Commentary by Charles Christopher Mierow, Ph.D., Instructor in Classics in Princeton University) (2006). Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889758-77-9.

Secondary sources

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1945). "The Legend of the Origin of the Huns". Byzantion. 17: 244–251.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture (Edited by Max Knight). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01596-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolfram, Herwig (1990). History of the Goths. University of California Press. p. 254. ISBN 0-5200-6983-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-5200-8511-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Pohl, Walter (1999). "Huns". In Bowersock, G. W.; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (eds.). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 501–502. ISBN 0-674-51173-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, E. A. (2001). The Huns. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-15899-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - James, Edward (2009). Europe's Barbarians, AD 200–600. Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77296-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973560-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wright, David Curtis (2011). The History of China. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-37748-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Atwood, Christopher P. (2012). "Huns and Xiōngnú: New Thoughts on an Old Problem". In Boeck, Brian J.; Martin, Russell E.; Rowland, Daniel (eds.). Dubitando: Studies in History and Culture in Honor of Donald Ostrowski. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–52. ISBN 978-0-8-9357-404-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hyun Jin Kim (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107009066.

- Hayashi, Toshio (2014). "Huns were Xiongnu or not? From the Viewpoint of Archaeological Material". In Choi, Han Woo; Şahin, Ilhan; Kim, Byung Il; İsakov, Baktıbek; Buyar, Cengiz (eds.). Altay Communities: Migrations and Emergence of Nations. Print(ist). pp. 27–52. ISBN 978-975-7914-43-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - de la Vaissière, Étienne (2015). "The Steppe World and the Rise of the Huns". In Maas, Michael (ed.). Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–192. ISBN 978-1-107-63388-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zhengzhang, Shangfang (2003). "古音字表". 上古音系. 上海教育出版社. pp. 260–581. ISBN 7-5320-9244-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Attila und die Hunnen. Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung. Hrsg. vom Historischen Museum der Pfalz, Speyer. (Stuttgart 2007).

- Christopher Kelly, Attila The Hun: Barbarian Terror and the Fall of the Roman Empire (London 2008)

- Rudi Paul Lindner, Nomadism, Horses and Huns, in: Past and Present 92, 1981, p. 3–19.

- E. A. Thompson, A History of Attila and the Huns (1948).

- Franz Altheim, Attila und die Hunnen (1951).

- J. Werner, Beiträge zur Archäologie des Attila-Reiches (1956).

- John Man, Attila The Hun, A barbarian King and the fall of Rome (2005).

- W. M. McGovern, Early Empires of Central Asia (1939)

- Frederick John Teggart, China and Rome (1969, repr. 1983);

External links

- Dorn'eich, Chris M. 2008. Chinese sources on the History of the Niusi-Wusi-Asi(oi)-Rishi(ka)-Arsi-Arshi-Ruzhi and their Kueishuang-Kushan Dynasty. Shiji 110/Hanshu 94A: The Xiongnu: Synopsis of Chinese original Text and several Western Translations with Extant Annotations. A blog on Central Asian history.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.