Lend-Lease

The Lend-Lease policy, formally titled "An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States", (Pub. L. 77–11, H.R. 1776, 55 Stat. 31, enacted March 11, 1941)[1] was a program under which the United States supplied Free France, the United Kingdom, the Republic of China, and later the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, and materiel between 1941 and August 1945. This included warships and warplanes, along with other weaponry. It was signed into law on March 11, 1941 and ended in September 1945. In general the aid was free, although some hardware (such as ships) were returned after the war. In return, the U.S. was given leases on army and naval bases in Allied territory during the war. Canada operated a similar smaller program under a different name.

A total of $50.1 billion (equivalent to $848 billion today) worth of supplies was shipped, or 17% of the total war expenditures of the U.S.[2] In all, $31.4 billion went to Britain, $11.3 billion to the Soviet Union, $3.2 billion to France, $1.6 billion to China, and the remaining $2.6 billion to the other Allies. Reverse Lend-Lease policies comprised services such as rent on air bases that went to the U.S., and totaled $7.8 billion; of this, $6.8 billion came from the British and the Commonwealth. The terms of the agreement provided that the materiel was to be used until returned or destroyed. In practice very little equipment was returned. Supplies that arrived after the termination date were sold to Britain at a large discount for £1.075 billion, using long-term loans from the United States. Canada operated a similar program called Mutual Aid that sent a loan of $1 billion and $3.4 billion in supplies and services to Britain and other Allies.[3][4]

This program effectively ended the United States' pretense of neutrality and was a decisive step away from non-interventionist policy, which had dominated United States foreign relations since 1931. (See Neutrality Acts of 1930s.)

Historical background

Following the Fall of France in June 1940, the British Commonwealth and Empire were the only forces engaged in war against Germany and Italy, until the Italian invasion of Greece. Britain had been paying for its material in gold under "cash and carry", as required by the US Neutrality Acts of the 1930s, but by 1941 it had liquidated so many assets that it was running short of cash.[5]

During this same period, the U.S. government began to mobilize for total war, instituting the first-ever peacetime draft and a fivefold increase in the defense budget (from $2 billion to $10 billion).[6] In the meantime, as the British began running short of money, arms, and other supplies, Prime Minister Winston Churchill pressed President Franklin D. Roosevelt for American help. Sympathetic to the British plight but hampered by public opinion and the Neutrality Acts, which forbade arms sales on credit or the loaning of money to belligerent nations, Roosevelt eventually came up with the idea of "Lend-Lease". As one Roosevelt biographer has characterized it: "If there was no practical alternative, there was certainly no moral one either. Britain and the Commonwealth were carrying the battle for all civilization, and the overwhelming majority of Americans, led in the late election by their president, wished to help them."[7] As the President himself put it, "There can be no reasoning with incendiary bombs."[8]

In September 1940, during the Battle of Britain the British government sent the Tizard Mission to the United States.[9] The aim of the British Technical and Scientific Mission was to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development work completed by the UK up to the beginning of World War II, but that Britain itself could not exploit due to the immediate requirements of war-related production. The shared technology included the cavity magnetron which the American historian James Phinney Baxter III later called "the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores".[10][11] the design for the VT fuze, details of Frank Whittle's jet engine and the Frisch–Peierls memorandum describing the feasibility of an atomic bomb.[12] Though these may be considered the most significant, many other items were also transported, including designs for rockets, superchargers, gyroscopic gunsights, submarine detection devices, self-sealing fuel tanks and plastic explosives.

In December 1940, President Roosevelt proclaimed the U.S. would be the "Arsenal of Democracy" and proposed selling munitions to Britain and Canada.[8] Isolationists were strongly opposed, warning it would lead to American involvement in what was seen by most Americans as an essentially European conflict. In time, opinion shifted as increasing numbers of Americans began to see the advantage of funding the British war against Germany, while staying out of the hostilities themselves.[13] Propaganda showing the devastation of British cities during The Blitz, as well as popular depictions of Germans as savage also rallied public opinion to the side of the Allies, especially after the Fall of France.

After a decade of neutrality, Roosevelt knew that the change to Allied support must be gradual, especially since German Americans were the largest ethnicity in America at the time. Originally, the American position was to help the British but not enter the war. In early February 1941, a Gallup poll revealed that 54 percent of Americans were in favor of giving aid to the British without qualifications of Lend-Lease. A further 15 percent were in favor with qualifications such as: "If it doesn't get us into war," or "If the British can give us some security for what we give them." Only 22 percent were unequivocally against the President's proposal. When poll participants were asked their party affiliation, the poll revealed a sharp political divide: 69 percent of Democrats were unequivocally in favor of Lend-Lease, whereas only 38 percent of Republicans favored the bill without qualification. At least one poll spokesperson also noted that, "approximately twice as many Republicans" gave "qualified answers as ... Democrats."[14]

Opposition to the Lend-Lease bill was strongest among isolationist Republicans in Congress, who feared the measure would be "the longest single step this nation has yet taken toward direct involvement in the war abroad." When the House of Representatives finally took a roll call vote on February 9, 1941, the 260 to 165 vote fell largely along party lines. Democrats voted 238 to 25 in favor and Republicans 24 in favor and 135 against.[15]

The vote in the Senate, which took place a month later, revealed a similar partisan divide. 49 Democrats (79 percent) voted "aye" with only 13 Democrats (21 percent) voting "nay." In contrast, 17 Republicans (63 percent) voted "nay" while 10 Senate Republicans (37 percent) sided with the Democrats to pass the bill.[16]

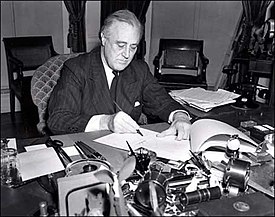

President Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease bill into law on 11 March 1941. It permitted him to "sell, transfer title to, exchange, lease, lend, or otherwise dispose of, to any such government [whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States] any defense article." In April, this policy was extended to China,[17] and in October to the Soviet Union. Roosevelt approved US $1 billion in Lend-Lease aid to Britain at the end of October 1941.

This followed the 1940 Destroyers for Bases Agreement, whereby 50 US Navy destroyers were transferred to the Royal Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy in exchange for basing rights in the Caribbean. Churchill also granted the US base rights in Bermuda and Newfoundland for free, allowing British military assets to be redeployed.[18]

Administration

President Roosevelt set up the Office of Lend-Lease Administration in 1941, appointing steel executive Edward R. Stettinius as head.[19] In September 1943, he was promoted to Undersecretary of State, and Leo Crowley became head of the Foreign Economic Administration which absorbed responsibility for Lend-Lease.

Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union was nominally managed by Stettinius. Roosevelt's Soviet Protocol Committee was dominated by Harry Hopkins and General John York, who were totally sympathetic to the provision of "unconditional aid", until 1943 few Americans objected to Soviet aid.[20]

The program began to be wound down after VE Day. In April 1945, Congress voted that it should not be used for post conflict purposes, and in August 1945, after Japanese surrender, the program was ended. Prior to his death in April of that year, Roosevelt had announced his intention to end the program from September 1945.[21]

Scale

Value of materials supplied by the USA to other allied nations [22]

| Country | Value in Millions of Dollars | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 31,387.1 | |||

| 372.0 | |||

| 10,982.1 | |||

| 39.2 | |||

| 3,223.9 | |||

| 21.6 | |||

| 1,627.0 | |||

| 18.9 | |||

| 251.1 | |||

| 8.3 | |||

| 159.5 | |||

| 7.8 | |||

| 81.5 | |||

| 7.1 | |||

| 47.0 | |||

| 6.6 | |||

| 42.9 | |||

| 5.5 | |||

| 32.2 | |||

| 4.5 | |||

| 19.0 | |||

| 2.6 | |||

| 12.5 | |||

| 2.0 | |||

| 11.6 | |||

| 1.6 | |||

| 5.3 | |||

| 1.4 | |||

| 5.3 | |||

| 0.9 | |||

| 4.4 | |||

| 0.9 | |||

| 0.9 | |||

| 0.4 | |||

| 0.6 | |||

| 0.2 | |||

| Total | 48,395.4 | ||

Significance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Lend-Lease would help the British and Allied forces win the battles of future years; the help it gave in the battles of 1941 was trivial.[23] In 1943–1944, about a quarter of all British munitions came through Lend-Lease. Aircraft (in particular transport aircraft) comprised about a quarter of the shipments to Britain, followed by food, land vehicles and ships.[citation needed]

Even after the United States forces in Europe and the Pacific began to reach full strength in 1943–1944, Lend-Lease continued. Most remaining allies were largely self-sufficient in front line equipment (such as tanks and fighter aircraft) by this stage, but Lend-Lease provided a useful supplement in this category even so, and Lend-Lease logistical supplies (including motor vehicles and railroad equipment) were of enormous assistance.[24]

Much of the aid can be better understood when considering the economic distortions caused by the war. Most belligerent powers cut back severely on production of non-essentials, concentrating on producing weapons. This inevitably produced shortages of related products needed by the military or as part of the military-industrial complex. For example, the USSR was highly dependent on rail transportation, but the war practically shut down rail equipment production. Just 446 locomotives were produced during the war,[25] with only 92 of those being built between 1942 and 1945.[26] In total, 92.7% of the wartime production of railroad equipment by the Soviet Union was supplied under Lend-Lease,[24] including 1,911 locomotives and 11,225 railcars[27] which augmented the existing prewar stocks of at least 20,000 locomotives and half a million railcars.[28]

Furthermore, the logistical support of the Soviet military was provided by hundreds of thousands of U.S.-made trucks. Indeed, by 1945, nearly a third of the truck strength of the Red Army was U.S.-built. Trucks such as the Dodge ¾ ton and Studebaker 2½ ton were easily the best trucks available in their class on either side on the Eastern Front. American shipments of telephone cable, aluminum, canned rations, and clothing were also critical.[29]

Lend-Lease also supplied significant amounts of weapons and ammunition. The Soviet air force received 18,700 aircraft, which amounted to about 30% of Soviet wartime aircraft production.[24] And while most tank units were equipped with Soviet-built models, some 7,000 Lend-Lease tanks were deployed by the Red Army.

According to the Russian historian Boris Vadimovich Sokolov, Lend-Lease played a crucial role in winning the war:

On the whole the following conclusion can be drawn: that without these Western shipments under Lend-Lease the Soviet Union not only would not have been able to win the Great Patriotic War, it would not have been able even to oppose the German invaders, since it could not itself produce sufficient quantities of arms and military equipment or adequate supplies of fuel and ammunition. The Soviet authorities were well aware of this dependency on Lend-Lease. Thus, Stalin told Harry Hopkins [FDR’s emissary to Moscow in July 1941] that the U.S.S.R. could not match Germany’s might as an occupier of Europe and its resources.[24]

Nikita Khrushchev, having served as a military commissar and intermediary between Stalin and his generals during the war, addressed directly the significance of Lend-lease aid in his memoirs:

I would like to express my candid opinion about Stalin’s views on whether the Red Army and the Soviet Union could have coped with Nazi Germany and survived the war without aid from the United States and Britain. First, I would like to tell about some remarks Stalin made and repeated several times when we were “discussing freely” among ourselves. He stated bluntly that if the United States had not helped us, we would not have won the war. If we had had to fight Nazi Germany one on one, we could not have stood up against Germany’s pressure, and we would have lost the war. No one ever discussed this subject officially, and I don’t think Stalin left any written evidence of his opinion, but I will state here that several times in conversations with me he noted that these were the actual circumstances. He never made a special point of holding a conversation on the subject, but when we were engaged in some kind of relaxed conversation, going over international questions of the past and present, and when we would return to the subject of the path we had traveled during the war, that is what he said. When I listened to his remarks, I was fully in agreement with him, and today I am even more so.[30]

In a confidential interview with the wartime correspondent Konstantin Simonov, the famous Soviet Marshal G.K. Zhukov is quoted as saying. “Today [1963] some say the Allies didn’t really help us… But listen, one cannot deny that the Americans shipped over to us material without which we could not have equipped our armies held in reserve or been able to continue the war.[31]

Quotations

Roosevelt, eager to ensure public consent for this controversial plan, explained to the public and the press that his plan was comparable to one neighbor's lending another a garden hose to put out a fire in his home. "What do I do in such a crisis?" the president asked at a press conference. "I don't say... 'Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it' …I don't want $15 — I want my garden hose back after the fire is over."[32] To which Senator Robert Taft (R-Ohio), responded: "Lending war equipment is a good deal like lending chewing gum. You don't want it back." In practice, very little was returned except for a few ships.

Joseph Stalin, during the Tehran Conference in 1943, acknowledged publicly the importance of American efforts during a dinner at the conference: "Without American production the United Nations [the Allies] could never have won the war."[33][34]

US deliveries to the Soviet Union

American deliveries to the Soviet Union can be divided into the following phases:

- "pre Lend-lease" 22 June 1941 to 30 September 1941 (paid for in gold and other minerals)

- first protocol period from 1 October 1941 to 30 June 1942 (signed 7 October 1941),[35] these supplies were to be manufactured and delivered by the UK with US credit financing.

- second protocol period from 1 July 1942 to 30 June 1943 (signed 6 October 1942)

- third protocol period from 1 July 1943 to 30 June 1944 (signed 19 October 1943)

- fourth protocol period from 1 July 1944, (signed 17 April 1945), formally ended 12 May 1945 but deliveries continued for the duration of the war with Japan (which the Soviet Union entered on the 8 August 1945) under the "Milepost" agreement until 2 September 1945 when Japan capitulated. On 20 September 1945 all Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union was terminated.

Delivery was via the Arctic Convoys, the Persian Corridor, and the Pacific Route.

The Arctic route was the shortest and most direct route for lend-lease aid to the USSR, though it was also the most dangerous. Some 3,964,000 tons of goods were shipped by the Arctic route; 7% was lost, while 93% arrived safely.[36] This constituted some 23% of the total aid to the USSR during the war.

The Persian Corridor was the longest route, and was not fully operational until mid-1942. Thereafter it saw the passage of 4,160,000 tons of goods, 27% of the total.[36]

The Pacific Route opened in August 1941, but was affected by the start of hostilities between Japan and the US; after December 1941, only Soviet ships could be used, and, as Japan and the USSR observed a strict neutrality towards each other, only non-military goods could be transported.[37] Nevertheless, some 8,244,000 tons of goods went by this route, 50% of the total.[36]

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11 billion in materials: over 400,000 jeeps and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks, about 1,386[38] of which were M3 Lees and 4,102 M4 Shermans);[39] 11,400 aircraft (4,719 of which were Bell P-39 Airacobras)[40] and 1.75 million tons of food.[41]

Roughly 17.5 million tons of military equipment, vehicles, industrial supplies, and food were shipped from the Western Hemisphere to the USSR, 94% coming from the US. For comparison, a total of 22 million tons landed in Europe to supply American forces from January 1942 to May 1945. It has been estimated that American deliveries to the USSR through the Persian Corridor alone were sufficient, by US Army standards, to maintain sixty combat divisions in the line.[42][43]

The United States gave to the Soviet Union from October 1, 1941 to May 31, 1945 the following: 427,284 trucks, 13,303 combat vehicles, 35,170 motorcycles, 2,328 ordnance service vehicles, 2,670,371 tons of petroleum products (gasoline and oil) or 57.8 percent of the High-octane aviation fuel,[24] 4,478,116 tons of foodstuffs (canned meats, sugar, flour, salt, etc.), 1,911 steam locomotives, 66 Diesel locomotives, 9,920 flat cars, 1,000 dump cars, 120 tank cars, and 35 heavy machinery cars. Provided ordnance goods (ammunition, artillery shells, mines, assorted explosives) amounted to 53 percent of total domestic production.[24] One item typical of many was a tire plant that was lifted bodily from the Ford Company's River Rouge Plant and transferred to the USSR. The 1947 money value of the supplies and services amounted to about eleven billion dollars.[44]

British deliveries to the Soviet Union

In June 1941, within weeks of the German invasion of the USSR, the first British aid convoy set off along the dangerous Arctic sea routes to Murmansk, arriving in September. It was carrying 40 Hawker Hurricanes along with 550 mechanics and pilots of No. 151 Wing to provide immediate air defence of the port and train Soviet pilots. After escorting Soviet bombers and scoring 14 kills for one loss, and completing the training of pilots and mechanics, No 151 Wing left in November, their mission complete.[45] The convoy was the first of many convoys to Murmansk and Archangelsk in what became known as the Arctic convoys, the returning ships carried the gold that the USSR was using to pay the US.

By the end of 1941, early shipments of Matilda, Valentine, and Tetrarch tanks represented only 6.5% of total Soviet tank strength, but over 25% of medium and heavy tanks in service with the Red Army.[46][47] First seeing action with the 138 Independent Tank Battalion in the Volga Reservoir on 20 November 1941,[48] Lend-Lease tanks constituted between 30 and 40% of heavy and medium tank strength before Moscow at the beginning of December 1941.[49][50]

Significant numbers of British Churchill, Matilda and Valentine tanks were shipped to the USSR along with the US M3 Lee after it became obsolete on the African Front, ceasing production in December 1942 and withdrawn from British service in May 1943.[51] The Churchills, supplied by the arctic convoys, saw action in the Siege of Leningrad and the Battle of Kursk,[52][53] while tanks shipped by the Persian route supplied the Caucasian Front. Between June 1941 and May 1945, Britain delivered to the USSR:

- 3,000+ Hurricanes

- 4,000+ other aircraft

- 27 naval vessels

- 5,218 tanks

- 5,000+ anti-tank guns

- 4,020 ambulances and trucks

- 323 machinery trucks

- 2,560 Universal Carriers

- 1,721 motorcycles

- £1.15bn worth of aircraft engines

- 600 radar and sonar sets

- Hundreds of naval guns

- 15 million pairs of boots

In total 4 million tonnes of war materials including food and medical supplies were delivered. The munitions totaled £308m (not including naval munitions supplied), the food and raw materials totaled £120m in 1946 index. In accordance with the Anglo-Soviet Military Supplies Agreement of 27 June 1942, military aid sent from Britain to the Soviet Union during the war was entirely free of charge.[54][55]

Soviet Cold War Characterization of U.S. Contributions

At the conclusion of WWII, and start of the Cold War, the government of the Soviet Union placed restrictions on access to war time archives and records. Many experts, both western and Soviet, have concluded that the Soviet rationale for these restrictions was an attempt to engage in a deliberate pattern of propaganda aimed at minimalizing allied support due to political motivations. Those motivations are alleged to include those long established hostilities which have pitted the Soviet socialist order against that of the Allied capitalist order.[56]

Alexander Dolitsky (The Executive Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center) offered a compelling explanation for Russia’s reluctance to acknowledge the significance of Lend-Lease when he stated that, “the Soviets efforts to minimize the role of lend-lease may have been motivated by considerations of national prestige and image.” [57] This view was supported by the famous Soviet Marshal G.K. Zhukov, who said in a confidential interview with the wartime correspondent Konstantin Simonov, that the Soviet government engaged in the calculated use of propaganda to systemically demean the importance of the Allied Lend-Lease Program, believing that it distracted from the heroism and sacrifice of the Soviet soldier and people.[57]

Robert Hill (author of Russia's life-saver: Lend-lease aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II) on the other hand, believed that the Soviets downplayed the significance of lend-lease in order to make a more political point, claiming that, “the Communist Party could claim to have both organized and inspired the Soviet people to achieve victory…”,[58] thereby strengthening their own position at home. Both rationales certainly go a long way toward supporting the arguments of Weeks, Hill, and Jones in explaining the Soviet need to minimize the significance of the Lend-Lease Program.

Following the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was greater access to Soviet war archives which lead both Western and Soviet historians to continue to attest to the significance of the US Lend-Lease program toward Soviet victory of the Eastern front. At the conclusion of the cold war, there was a change amongst the Soviet historians regarding the significance of the Lend-Lease program, one which more closely aligns with that of the Allied facts and figures. For example, Russian historian Boris Sokolov dismissed the often cited Soviet figure of 4% Allied contribution of military aid under lend-lease as an, “egregious error …made by Soviet propagandists.”[59] According to Sokolov the true figures of the Lend-Lease Program were much higher than the 4% figures used in Soviet historical works, and in fact were, “anywhere from 15% to 25% and in some cases upwards towards to 50% [depending upon the] various types of military goods as a percentage of what the Soviets themselves were able to produce”.[60]

Robert Jones, in his work, The Roads to Russia also argues in support of the significance of the Lend-Lease Program claiming that, “the United States aid to Russia played a much more vital war role than it would appear from the cold [war] statistics.” [61] Jones argued along similar lines as Weeks, also points out that by the end of the war Russia went to great lengths to disregard the significance of Lend-Lease. In fact Jones argued that had the Soviet Union published the true extent to which the Lend-Lease Program aided the Soviets, it would have exposed the Soviet Union to “the lie [of]her own propaganda”.[62]

Reverse Lend-lease

Reverse Lend-lease was the supply of equipment and services to the United States. Nearly $8 billion worth of war material was provided to U.S. forces by her allies, 90% of this sum coming from the British Empire.[63] Reciprocal contributions included the Austin K2/Y military ambulance, British aviation spark plugs used in B-17 Flying Fortresses,[63] Canadian-made Fairmile launches used in anti-submarine warfare, Mosquito photo-reconnaissance aircraft, and Indian petroleum products.[64] Australia and New Zealand supplied the bulk of foodstuffs to United States forces in the South Pacific.[63][65] Though diminutive in comparison, Soviet-supplied reverse lend-lease included 300,000 metric tons of chromium and 32,000 metric tons of manganese ore, as well as wood, gold and platinum.[66]

In a November 1943 report to Congress, President Roosevelt said of Allied participation in reverse Lend-lease:

...the expenditures made by the British Commonwealth of Nations for reverse lend-lease aid furnished to the United States, and of the expansion of this program so as to include exports of materials and foodstuffs for the account of United States agencies from the United Kingdom and the British colonies, emphasizes the contribution which the British Commonwealth has made to the defense of the United States while taking its place on the battle fronts. It is an indication of the extent to which the British have been able to pool their resources with ours so that the needed weapon may be in the hands of that soldier—whatever may be his nationality- who can at the proper moment use it most effectively to defeat our common enemies.[64]

In 1945–46, the value of Reciprocal Aid from New Zealand exceeded that of Lend-Lease, though in 1942–43, the value of Lend-Lease to New Zealand was much more than that of Reciprocal Aid. Britain also supplied extensive material assistance to American forces stationed in Europe, for example the USAAF was supplied with hundreds of Spitfire Mk V and Mk VIII fighter aircraft.

The cooperation that was built up with Canada during the war was an amalgam compounded of diverse elements of which the air and land routes to Alaska, the Canol project, and the CRYSTAL and CRIMSON activities were the most costly in point of effort and funds expended.

... The total of defense materials and services that Canada received through lend-lease channels amounted in value to approximately $419,500,000.

... Some idea of the scope of economic collaboration can be had from the fact that from the beginning of 1942 through 1945 Canada, on her part, furnished the United States with $1,000,000,000 to $1,250,000,000 in defense materials and services.

... Although most of the actual construction of joint defense facilities, except the Alaska Highway and the Canol project, had been carried out by Canada, most of the original cost was borne by the United States. The agreement was that all temporary construction for the use of American forces and all permanent construction required by the United States forces beyond Canadian requirements would be paid for by the United States, and that the cost of all other construction of permanent value would be met by Canada. Although it was not entirely reasonable that Canada should pay for any construction that the Canadian Government considered unnecessary or that did not conform to Canadian requirements, nevertheless considerations of self-respect and national sovereignty led the Canadian Government to suggest a new financial agreement.

... The total amount that Canada agreed to pay under the new arrangement came to about $76,800,000, which was some $13,870,000 less than the United States had spent on the facilities.[67]

Canadian aid to the Allied effort

Britain's lend-lease arrangements with its dominions and colonies is one of the lesser known parts of World War II history.

"Mutual Aid" was "the Canadian version of lend-lease," says Muirhead.[68] Canada gave Britain gifts totaling $3.5 billion during the war, plus a zero-interest loan of $1 billion; Britain used the money to buy Canadian food and war supplies.[69][70][71] Canada also loaned $1.2 billion on a long-term basis to Britain immediately after the war; these loans were fully repaid in late 2006.[72]

The Gander Air Base (RCAF Station Gander) located at Gander International Airport built in 1936 in Newfoundland was leased by Britain to Canada for 99 years because of its urgent need for the movement of fighter and bomber aircraft to Britain.[73] The lease became redundant when Newfoundland became Canada's tenth province in 1949.

Most American Lend-Lease aid comprised supplies purchased in the U.S., but Roosevelt allowed Lend-Lease to purchase supplies from Canada, for shipment to Britain, China and Soviet Union.[74]

Repayment

Congress had not authorized the gift of supplies delivered after the cutoff date, so the U.S. charged for them, usually at a 90% discount. Large quantities of undelivered goods were in Britain or in transit when Lend-Lease terminated on 2 September 1945. Britain wished to retain some of this equipment in the immediate post war period. In 1946, the post-war Anglo-American loan further indebted Britain to the U.S. Lend-Lease items retained were sold to Britain at 10% of nominal value, giving an initial loan value of £1.075 billion for the Lend-Lease portion of the post-war loans. Payment was to be stretched out over 50 annual payments, starting in 1951 and with five years of deferred payments, at 2% interest.[75] The final payment of $83.3 million (£42.5 million), due on 31 December 2006 (repayment having been deferred in the allowed five years and during a sixth year not allowed), was made on 29 December 2006 (the last working day of the year). After this final payment Britain's Economic Secretary to the Treasury formally thanked the U.S. for its wartime support.

Tacit repayment of Lend-Lease by the British was made in the form of several valuable technologies, including those related to radar, sonar, jet engines, antitank weaponry, rockets, superchargers, gyroscopic gunsights, submarine detection, self-sealing fuel tanks, and plastic explosives as well as the British contribution to the Manhattan Project. Many of these were transferred by the Tizard Mission. The official historian of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, James Phinney Baxter III, wrote: "When the members of the Tizard Mission brought the cavity magnetron to America in 1940, they carried the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores."

While repayment of the interest-free loans was required after the end of the war under the act, in practice the U.S. did not expect to be repaid by the USSR after the war. The U.S. received $2M in reverse Lend-Lease from the USSR. This was mostly in the form of landing, servicing, and refueling of transport aircraft; some industrial machinery and rare minerals were sent to the U.S. The U.S. asked for $1.3B at the cessation of hostilities to settle the debt, but was only offered $170M by the USSR. The dispute remained unresolved until 1972, when the U.S. accepted an offer from the USSR to repay $722M linked to grain shipments from the U.S., with the remainder being written off. During the war the USSR provided an unknown number of shipments of rare minerals to the US Treasury as a form of cashless repayment of Lend-Lease. This was agreed upon before the signing of the first protocol on 1 October 1941 and extension of credit. Some of these shipments were intercepted by the Germans. In May 1942, the HMS Edinburgh was sunk while carrying 4.5 tonnes of Soviet gold intended for the U.S. Treasury. This gold was salvaged in 1981 and 1986.[citation needed] In June 1942, the SS Port Nicholson was sunk en route from Halifax, Canada to New York, allegedly with Soviet platinum, gold, and industrial diamonds aboard.[76] However, none of this cargo has been salvaged, and no documentation of it has been produced.

See also

- ALSIB

- Anglo-American loan

- Arctic convoys of World War II

- Arms Export Control Act

- Billion Dollar Gift and Mutual Aid, from Canada

- Banff-class sloop

- Battle of the Atlantic

- Cash and carry (World War II)

- Houses for Britain

- Lend-Lease Sherman tanks

- Military production during World War II

- Northwest Staging Route

- Operation Cedar

- Persian Corridor

- Project Hula

- Tizard Mission

References

Citations

- ^ Crossed Currents. p. 28.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ McNeill. America, Britain and Russia. p. 778.

- ^ Granatstein, J.L. (1990). Canada's War: The Politics of the Mackenzie King Government, 1939-1945. p. 315.

- ^ Crowley, Leo T. "Lend-Lease" in Walter Yust, ed., 10 Eventful Years (Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 1947), 1:520, 2:858–860.

- ^ Allen 1955, pp. 807–912.

- ^ ”17 Billion Budget Drafted; Defense Takes 10 Billions.” The New York Times, 28 December 1940.

- ^ Black 2003, pp. 603–605.

- ^ a b "Address Is Spur To British Hopes; Confirmation of American Aid in Conflict is Viewed as Heartening, A joining of interests, Discarding of Peace Talks is Regarded as a Major Point in the Speech." The New York Times, 30 December 1940.

- ^ Hind, Angela (5 February 2007). "Briefcase 'that changed the world'". BBC News. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ James Phinney Baxter III (Official Historian of the Office of Scientific Research and Development), Scientists Against Time (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1946), page 142.

- ^ Newsweek, 12/1/97, http://www.newsweek.com/radar-169944

- ^ Brennen, James W. (September 1968), The Proximity Fuze Whose Brainchild?, United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- ^ Kimball 1969

- ^ "Bill to Aid Britain Strongly Backed." The New York Times, 9 February 1941.

- ^ Dorris, Henry. "No Vital Changes." The New York Times, 9 February 1941.

- ^ Hinton, Harold B. "All Curbs Downed." The New York Times, 9 March 1941.

- ^ Weeks 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Neiberg 2004, pp. 118–119.

- ^ "America Reports On Aid To Allies etc. (1942)." Universal Newsreel, 1942. Retrieved: 22 February 2012.

- ^ Weiss 1996, p. 220.

- ^ Alfred F. Havighurst. Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century. p. 390. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Wolfgang Schumann (et al.): Deutschland im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1982, Bd. 3, S. 468.(German Language)

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Weeks 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Budnitsky, Oleg. "Russian historian: Importance of Lend-Lease cannot be overestimated". Russia Beyond the Headlines (Interview).

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union, 1941-45: A Documentary Reader. p. 188.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Weeks 2004, p. 146.

- ^ "Russia and Serbia, A Century of Progress in Rail Transport". A Look at Railways History in 1935 and Before. Open Publishing. July 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Weeks 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Khrushchev, Nikita (2005). Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Commissar, 1918-1945, Volume 1. Sergei Khrushchev. Pennsylvania State Univ Pr. pp. 675–676. ISBN 978-0271058535.

- ^ Albert L. Weeks The Other Side of Coexistence: An Analysis of Russian Foreign Policy, (New York, Pittman Publishing Corporation, 1974), p.94, quoted in Albert L. Weeks, Russia’s Life-Saver: Lend-Lease Aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II (New York: Lexington Books, 2010), 1

- ^ 17 December 1940 Press Conference

- ^ "One War Won." Time Magazine, 13 December 1943.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 8, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ^ The United States at war; development and administration of the war program by the federal government (Report). Bureau of the Budget. 1946. p. 82. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

On October 7, 1941, the President approved the Moscow Protocol under which it was agreed to furnish certain materials to Russia.

- ^ a b c Kemp p235

- ^ Sea routes of Soviet Lend-Lease:Voice of Russia Ruvr.ru. Retrieved: 16 December 2011

- ^ Zaloga (Armored Thunderbolt) p. 28, 30, 31

- ^ Lend-Lease Shipments: World War II, Section IIIB, Published by Office, Chief of Finance, War Department, 31 December 1946, p. 8.

- ^ Hardesty 1991, p. 253.

- ^ World War II The War Against Germany And Italy, US Army Center Of Military History, page 158.

- ^ "The five Lend-Lease routes to Russia". Engines of the Red Army. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Motter, T.H. Vail (1952). The Persian Corridor and Aid to Russia. Center of Military History. pp. 4–6. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Deane, John R. 1947. The Strange Alliance, The Story of Our Efforts at Wartime Co-operation with Russia. The Viking Press.

- ^ Paul Dean, special to Russia Now (30 June 2011). "When Britain aided the Soviet Union in World War Two". Telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Krivosheev, G.F. (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. London: Greenhill Books. p. 252. ISBN 978-1853672804.

- ^ Suprun, Mikhail (1997). Ленд-лиз и северные конвои (Lend-Lease and Northern Convoys), 1941-1945. Moscow: Андреевский флаг. p. 358. ISBN 5-85608-081-5.

- ^ Secret Cipher Telegram. From: 30 Military Mission. To: The War Office. Recd 11/12/41. TNA WO 193/580

- ^ Hill, Alexander (2006). "British "Lend-Lease" Tanks and the Battle for Moscow, November–December 1941". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 19 (2). doi:10.1080/13518040600697811. Retrieved 1 September 2016 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Biriukov, Nikolai (2005). Tanki – frontu! Zapiski sovetskogo generala (Tanks-front! Notes of a Soviet General). Smolensk: Rusich. p. 57. ISBN 978-5813806612.

- ^ "Medium Tank M3/ Grant/ Lee". Historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ^ "Churchill tank". Tanks Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Did Russia Really Go It Alone? How Lend-Lease Helped the Soviets Defeat the Germans". HistoryNet.

- ^ "ВИФ2 NE : Ветка : Re: А разве". Vif2ne.org. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ^ "RUSSIA (BRITISH EMPIRE WAR ASSISTANCE)". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ^ Tom White, The Significance of the Allied Lend-Lease Program and Soviet Victory during the Second World War https://perspectivesofthepast.com/europe-in-the-era-of-the-world-wars/the-significance-of-the-allied-lend-lease-program-and-soviet-victory-during-the-second-world-war

- ^ a b Weeks, Russia’s Life-Saver: Lend-Lease Aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II , 126

- ^ Alexander Hill, “British Lend Lease Aid and the Soviet War Effort, June 1941-1942.” The Journal of Military History 71, no. 3 (2007): pp. 773-808. Accessed November 1, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30052890., 774

- ^ Weeks, Russia’s Life-Saver: Lend-Lease Aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II , 8

- ^ Ibid

- ^ Robert H. Jones, The Roads to Russia: United States Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969), 238

- ^ Jones, The Roads to Russia: United States Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union, 250

- ^ a b c Schreiber, O. (Sep 1951). "Tenth Anniversary of Lend-Lease: How America Gave Aid to Her Allies". The Australian Quarterly. 23 (3). doi:10.2307/20633372. JSTOR 20633372.

- ^ a b "Report to Congress on Reverse Lend-Lease". American Presidency Project. November 11, 1943.

- ^ BAKER, J. V. T. (1965). War Economy. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch.

- ^ Chaplygin, Andrey (May 2016). "ЗНАЧЕНИЕ ЛЕНД-ЛИЗА ДЛЯ СССР (Value of Lend Lease to the USSR)". историк. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Conn, Stetson and Byron Fairchild. "Chapter XIV: The United States and Canada: Copartners in Defense." United States Army in World War II – The Western Hemisphere – The Framework of Hemisphere Defense, The United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved: 9 December 2010.

- ^ B. Muirhead (1992). Development of Postwar Canadian Trade Policy: The Failure of the Anglo-European Option. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 180.

- ^ Granatstein 1990, pp. 194, 315.

- ^ C.P. Stacey, and Norman Hillmer, ed. "Second World War (WWII)." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved: 17 October 2011.

- ^ Robert B. Bryce, Canada and the Cost of World War II: The International Operations of Canada's Department of Finance, 1939-1947 (2005) ch 7

- ^ "Britain makes final WW2 lend-lease payment." Inthenews.co.uk. Retrieved: 8 December 2010.

- ^ Stacey 1970, pp. 361, 374, 377.

- ^ Stacey 1970, p. 490.

- ^ Kindleberger 1984, p. 415.

- ^ Henderson, Barney; agencies (February 2, 2012). "Treasure hunters 'find $3 billion in platinum on sunken WW2 British ship'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

Bibliography

- Allen, H.C. Britain and the United States. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1955.

- Allen, R.G.D. "Mutual Aid between the US and the British Empire, 1941—5". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Volume 109, No. 3, 1946, pp. 243–277, online in JSTOR

- Black, Conrad. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Champion of Freedom. New York: Public Affairs, 2003. ISBN 1-58648-184-3.

- Bryce, Robert B. Canada and the Cost of World War II: The International Operations of Canada's Department of Finance, 1939-1947 (2005) ch 7 on Mutual Aid

- Buchanan, Patrick. Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War. New York: Crown, 2008. ISBN 978-0-307-40515-9.

- Campbell, Thomas M. and George C. Herring, eds. The Diaries of Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., 1943–1946. New York: Franklin Watts, Inc., 1975. ISBN 0-531-05570-1.

- Clarke, Sir Richard. Anglo-American Economic Collaboration in War and Peace, 1942–1949. Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-19-828439-X.

- Crowley, Leo T. "Lend Lease" in Walter Yust, ed. 10 Eventful Years, 1937 – 1946 Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1947, pp. 858–860.

- Dawson, Raymond H. The Decision to Aid Russia, 1941: Foreign Policy and Domestic Politics. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1959.

- Dobson, Alan P. U.S. Wartime Aid to Britain, 1940–1946. London: Croom Helm, 1986. ISBN 0-7099-0893-8.

- Gardner, Richard N. Sterling-Dollar Diplomacy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956.

- Granatstein, J. L. Canada's War: The Politics of the McKenzie King Government, 1939–1945. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Firefly Books, 1990. ISBN 0-88619-356-7.

- Hancock, G.W. and M.M. Gowing. British War Economy (1949) pp 224–48 Official British history

- Herring Jr. George C. Aid to Russia, 1941–1946: Strategy, Diplomacy, the Origins of the Cold War. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973. ISBN 0-231-03336-2.

- Kemp, P. Convoy: Drama in Arctic Waters. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Book Sales Inc., 2004, First edition 1993. ISBN 978-0-78581-603-4.

- Kimball, Warren F. The Most Unsordid Act: Lend-Lease, 1939–1941. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University, 1969. ISBN 0-8018-1017-5.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. A Financial History of Western Europe. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-19-507738-5.

- Langer, William L. and S. Everett Gleason. "Chapters: 8–9." The Undeclared War, 1940–1941. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953.

- Louis, William Roger. Imperialism at Bay: The United States and the Decolonization of the British Empire, 1941–1945. Oxford University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-19-821125-2.

- Mackenzie, Hector. "Transatlantic Generosity: Canada's ‘Billion Dollar Gift’ to the United Kingdom in the Second World War." International History Review, Volume 24, Issue 2, 2012, pp. 293–314.

- McNeill, William Hardy. America, Britain, and Russia: their co-operation and conflict, 1941-1946 (1953), pp 772–90

- Milward, Alan S. War, Economy and Society. Harmondsworth: Pelican, 1977. ISBN 0-14-022682-6.

- Neiberg, Michael S. Warfare and Society in Europe: 1898 to the Present. London: Psychology Press, 2004. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-415-32719-0.

- Reynolds, David. The Creation of the Anglo-American Alliance 1937–1941: A Study on Competitive Cooperation. London: Europa, 1981. ISBN 0-905118-68-5.

- Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland. Stilwell's Mission to China. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army, 1953.

- Sayers, R.S. Financial Policy, 1939–45. London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1956.

- Schama, Simon. A History of Britain, Vol. III. New York: Hyperion, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7868-6899-5.

- Sherwood, Robert E. Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History. New York: Enigma Books, 2008, First edition 1948 (1949 Pulitzer Prize winner). ISBN 978-1-929631-49-0.

- Stacey, C.P. Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada 1939–1945. Ottawa, Canada: The Queen's Printer for Canada, 1970. ISBN 0-8020-6560-0.

- Stettinius, Edward R. Lend-Lease, Weapon for Victory. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1944. OCLC 394271

- Taylor, A. J. P. Beaverbrook. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972. ISBN 0-671-21376-8.

- Thorne, Christopher. Allies of a Kind: The United States, Britain and the War Against Japan, 1941–1945. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-19-520173-6.

- Twenty-first Report to Congress on Lend-Lease Operations, p. 25.

- Weeks, Albert L. Russia's Life-Saver: Lend-Lease Aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2004. ISBN 978-0-7391-0736-2.

- Weiss, Stuart L. The President's Man: Leo Crowley and Franklin Roosevelt in Peace and War. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8093-1996-9.

- Woods, Randall Bennett. A Changing of the Guard: Anglo-American Relations, 1941–1946. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8078-1877-1.

External links

- Lend-Lease Shipments, World War II (Washington: War Department, 1946)

- Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union

- The Voice of Russia on the Allies and Lend-Lease Museum, Moscow

- Official New Zealand war history of Lend-lease, from War Economy

- Official New Zealand war history; termination of Mutual Aid from 21 December 1945, from War Economy

- Allies and Lend-Lease Museum, Moscow

- "Reverse Lend-Lease" a 1944 Flight article reporting a speech by President Roosevelt

- Lend lease routes - map and summary of quantities of LL to USSR

- 1941 in the United States

- Economic aid during World War II

- History of the United States (1918–45)

- Military history of the United States during World War II

- Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Soviet Union–United States relations

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- United States federal commerce legislation

- United States foreign relations legislation

- 1939 in international relations

- Military logistics of World War II

- 1940s economic history

- Foreign trade of the Soviet Union

- British Empire in World War II

- United Kingdom in World War II