Milk (2008 American film): Difference between revisions

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

A.O. Scott of ''[[The New York Times]]'' called ''Milk'', "A Marvel", and wrote the film "is a fascinating, multi-layered history lesson. In its scale and visual variety it feels almost like a calmed-down Oliver Stone movie, stripped of hyperbole and [[Oedipus|Oedipal]] melodrama. But it is also a film that like Mr. Van Sant’s other recent work — and also, curiously, like [[David Fincher]]’s ''[[Zodiac (2007 film)|Zodiac]]'', another San Francisco-based tale of the 1970s — respects the limits of [[psychology|psychological]] and [[sociology|sociological]] explanation."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://movies.nytimes.com/2008/11/26/movies/26milk.html?ref=movies|title=Movie Review - Milk|author=[[A.O. Scott]]|publisher=''[[The New York Times]]''|date=2008-11-26}}</ref> |

A.O. Scott of ''[[The New York Times]]'' called ''Milk'', "A Marvel", and wrote the film "is a fascinating, multi-layered history lesson. In its scale and visual variety it feels almost like a calmed-down Oliver Stone movie, stripped of hyperbole and [[Oedipus|Oedipal]] melodrama. But it is also a film that like Mr. Van Sant’s other recent work — and also, curiously, like [[David Fincher]]’s ''[[Zodiac (2007 film)|Zodiac]]'', another San Francisco-based tale of the 1970s — respects the limits of [[psychology|psychological]] and [[sociology|sociological]] explanation."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://movies.nytimes.com/2008/11/26/movies/26milk.html?ref=movies|title=Movie Review - Milk|author=[[A.O. Scott]]|publisher=''[[The New York Times]]''|date=2008-11-26}}</ref> |

||

''[[Christianity Today]]'', a major [[progressive Christian]]-faith based periodical, gave the film a positive response.<ref name=today/> It stated that "''Milk'' achieves what it sets out to do, telling an inspiring tale of one man's quest to legitimize his identity, to give hope to his community. I'm not sure how well it'll play outside of big cities, or if it will sway any opinions on hot-button political issues, but it gives a valiant, empathetic go of it." It also stated that the portrayal of [[Dan White]] was very fair and humanized and portrayed as more of a flawed and tragically opinionated character, rather than a "typical 'crazy Christian villain' stereotype".<ref name=today>{{cite web|url=http://www.christianitytoday.com/movies/reviews/2008/milk.html|title=Milk|publisher=''[[Christianity Today]]''|accessdate=2008-11-26}}</ref> |

''[[Christianity Today]]'', a major [[progressive Christian]]-faith based periodical, gave the film a positive response.<ref name=today/> It stated that "''Milk'' achieves what it sets out to do, telling an inspiring tale of one man's quest to legitimize his identity, to give hope to his community. I'm not sure how well it'll play outside of big cities, or if it will sway any opinions on hot-button political issues, but it gives a valiant, empathetic go of it." It also stated that the portrayal of [[Dan White]] was very fair and humanized and portrayed as more of a flawed and tragically opinionated character, rather than a "typical 'crazy Christian villain' stereotype".<ref name=today>{{cite web|url=http://www.christianitytoday.com/movies/reviews/2008/milk.html|title=Milk|publisher=''[[Christianity Today]]''|accessdate=2008-11-26}}</ref> That was often shown in many gay themed films. |

||

In contrast, [[John Podhoretz]] of the [[neoconservative]] magazine ''[[Weekly Standard]]'' blasted the portrayal of Harvey Milk, saying that it treated the "smart, aggressive, purposefully offensive, press-savvy" activist like a "teddy bear". Podhoretz also argued that the film glosses over Milk's [[polyamorous]] [[Polyamorous#Polyamory_in_a_same-sex_setting|relationships]]; he opined that this contrasts Milk from present day gay rights activists fighting over [[monogamous]] [[same-sex marriage]].<ref name=rose>[http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/015/896jzzha.asp Rose-Colored Milk]. By [[John Podhoretz]]. ''[[Weekly Standard]]''. Published December 6, 2008. Accessed December 12, 2008.</ref> |

In contrast, [[John Podhoretz]] of the [[neoconservative]] magazine ''[[Weekly Standard]]'' blasted the portrayal of Harvey Milk, saying that it treated the "smart, aggressive, purposefully offensive, press-savvy" activist like a "teddy bear". Podhoretz also argued that the film glosses over Milk's [[polyamorous]] [[Polyamorous#Polyamory_in_a_same-sex_setting|relationships]]; he opined that this contrasts Milk from present day gay rights activists fighting over [[monogamous]] [[same-sex marriage]].<ref name=rose>[http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/015/896jzzha.asp Rose-Colored Milk]. By [[John Podhoretz]]. ''[[Weekly Standard]]''. Published December 6, 2008. Accessed December 12, 2008.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:08, 7 March 2009

| Milk | |

|---|---|

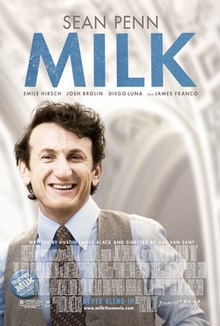

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gus Van Sant |

| Written by | Dustin Lance Black |

| Produced by | Dan Jinks Bruce Cohen |

| Starring | Sean Penn Emile Hirsch Josh Brolin Diego Luna James Franco |

| Cinematography | Harris Savides |

| Edited by | Elliot Graham |

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

| Distributed by | Focus Features |

Release dates | November 26, 2008 (limited) January 30, 2009 (wide) |

Running time | 128 min. |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15,000,000 |

| Box office | $35,179,492 |

Milk is a 2008 biographical film on the life of gay rights activist and politician Harvey Milk, who was the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Directed by Gus Van Sant, it stars Sean Penn as Milk and Josh Brolin as Milk's assassin, Supervisor Dan White. The film was acclaimed when released and earned numerous accolades from film critics and guilds. Ultimately, it received 8 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, winning two for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Penn and Best Original Screenplay for Dustin Lance Black.

Attempts to put Milk's life to film followed a 1984 Oscar-winning documentary of his life and the aftermath of his assassination, titled The Times of Harvey Milk, which was loosely based upon Randy Shilts' biography, The Mayor of Castro Street. Various scripts were considered in the early 1990s, but projects fell through for different reasons, until 2007. Much of Milk was filmed on Castro Street and various locations in San Francisco, including Milk's former storefront, Castro Camera.

Milk begins on Harvey Milk's 40th birthday, when he was living in New York and had not yet settled in San Francisco. It chronicles his foray into city politics, and the various battles he waged in the Castro neighborhood as well as throughout the city, and political campaigns to limit the rights of gay people in 1977 and 1978 run by Anita Bryant and John Briggs. His romantic and political relationships are also addressed, as is his tenuous affiliation with troubled Supervisor Dan White; the film ends with White's double murder of Milk and Mayor George Moscone. The film's release was tied to the 2008 California voter referendum on gay marriage, Proposition 8, when it made its premiere at the Castro Theater two weeks before election day.

Plot summary

Milk opens with archival footage of police raiding gay bars and arresting patrons during the 1950s and 1960s, followed by Dianne Feinstein's November 27, 1978, announcement to the press that Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone have been assassinated. Milk is seen recording his will throughout the film, nine days (November 18, 1978) before the assassinations. The film then flashes back to New York City in 1970, the eve of Milk's 40th birthday and his first meeting with his much younger lover, Scott Smith.

Unsatisfied with his life and in need of a change, Milk and Smith decide to move to San Francisco in the hope of finding larger acceptance of their relationship. They open Castro Camera in the heart of Eureka Valley, a working class neighborhood in the process of evolving into a predominantly gay neighborhood known as The Castro. Frustrated by the opposition they encounter in the once Irish-Catholic neighborhood, Milk utilizes his background as a businessman to become a gay activist, eventually becoming a mentor for Cleve Jones. Early on, Smith serves as Milk's campaign manager, but his frustration grows with Milk's obsessive devotion to politics, and he leaves him. Milk later meets Jack Lira, a sweet-natured but unbalanced young man. As with Smith, however, Lira cannot tolerate Milk's devotion to political activism, and eventually hangs himself.

After two unsuccessful political campaigns in 1973 and 1975 to become a city supervisor and a third in 1976 for the California State Assembly, Milk finally wins a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977 for District 5. His victory makes him the first openly gay man to be voted into major public office in the United States. Milk subsequently meets fellow Supervisor Dan White, a Vietnam veteran and former police officer and firefighter. White, who is politically and socially conservative, has a difficult relationship with Milk. He has a growing resentment for Milk, largely due to the attention paid to Milk by the press and his colleagues.

Milk and White forge a complex working relationship. Milk is invited to, and attends, the christening of White's first child, and White asks for Milk's assistance in preventing a psychiatric hospital from opening in White's district, possibly in exchange for White's support of Milk's citywide gay rights ordinance. When Milk fails to support White, White feels betrayed, and ultimately becomes the sole vote against the gay rights ordinance. Milk also launches an effort to defeat Proposition 6, an initiative on the California state ballot in November 1978. Sponsored by John Briggs, a conservative state legislator from Orange County, Proposition 6 seeks to ban gays and lesbians (in addition to anyone who supports them) from working in California's public schools. It is also part of a nationwide conservative movement that starts with the successful campaign headed by Anita Bryant and her organization Save Our Children in Dade County, Florida to repeal a local gay rights ordinance. On November 7, 1978, after working tirelessly against Proposition 6, Milk and his supporters rejoice in the wake of its defeat. The increasingly unstable White is in favor of a supervisor pay raise, but does not get much support, and shortly after supporting the Proposition, resigns from the Board. He later changes his mind and asks the city to rescind his decision. Mayor George Moscone denies his request, after having been lobbied by Milk to do so.

On the morning of November 27, 1978, White enters San Francisco City Hall through a basement window in order to conceal a gun from metal detectors. He requests another meeting with Moscone, who rebuffs his request for re-appointment. Enraged, White shoots Moscone and then Milk. The film suggests that Milk believed that White might be a closeted gay man.[1]

The film ends with an aerial shot of the candlelight vigil held by thousands for Milk and Moscone throughout the streets of the city.

Cast

- Sean Penn as Harvey Milk

- Emile Hirsch as Cleve Jones

- James Franco as Scott Smith

- Josh Brolin as Dan White

- Victor Garber as Mayor George Moscone

- Denis O'Hare as Senator John Briggs

- Diego Luna as Jack Lira

- Ashlee Temple as Dianne Feinstein

- Alison Pill as Anne Kronenberg

- Lucas Grabeel as Danny Nicoletta

- Stephen Spinella as Rick Stokes

- Joseph Cross as Dick Pabich

- Jeff Koons as Art Agnos

A number of Milk's associates, including speechwriter Frank M. Robinson, Teamster Allan Baird and schoolteacher-turned-politician Tom Ammiano portrayed themselves. Additionally, Carol Ruth Silver, who served with Milk on the Board of Supervisors, plays a small role.

Production

In early 1991, Oliver Stone was planning to produce, but not direct, a movie on Milk's life;[2] he wrote a script for the movie, called The Mayor of Castro Street.[3] In July 1992, director Gus Van Sant was signed with Warner Bros. to direct the biopic with actor Robin Williams in the lead role.[4] By April 1993, Van Sant parted ways with the studio, citing creative differences. Other actors considered for Harvey Milk at time were Richard Gere, Daniel Day-Lewis and James Woods[5] In April 2007, the director sought to direct the biopic based on a script by Dustin Lance Black, while at the same time, director Bryan Singer was developing The Mayor of Castro Street, which had been in development hell.[6] By the following September, Sean Penn was attached to play Harvey Milk and Matt Damon was attached to play Milk's assassin, Dan White.[7] Damon pulled out later in September due to scheduling conflicts.[8] By November, Focus Features moved forward with Van Sant's production, Milk, while Singer's project ran into trouble with the writers' strike.[9] In December 2007, actors Josh Brolin, Emile Hirsch, Alison Pill, and James Franco joined Milk, with Brolin replacing Damon as Dan White.[10] Milk began filming on location in San Francisco in January 2008.[11]

Filmmakers researched San Francisco's history in the city's Gay and Lesbian Archives and talked to people who knew Milk to shape their approach to the era. They also revisited the location of Milk's camera shop on Castro Street and dressed the street to match the film's 1970s setting. The camera shop, which had become a gift shop, was bought out by filmmakers for a couple of months to use in production. Production on Castro Street also revitalized the Castro Theatre, whose facade was repainted and whose neon marquee was redone. Filming also took place at the San Francisco City Hall, while White's office, where Milk was assassinated, was recreated elsewhere due to the city hall's offices having become more modern. Filmmakers also intended to show a view of the San Francisco Opera House from the redesign of White's office.[12] Filming finished March 2008.[13]

Release

In the month leading up to Milk's release, Focus Features kept the film out of fall film festivals and restricted media screenings, seeking to briefly avoid word-of-mouth and the partisanship it could generate. Milk premiered in San Francisco on October 28, 2008, initiating a marketing dilemma that Focus Features struggled to face due to the film's subject matter. The studio hoped to stay above the politics of the ongoing general elections, especially California's anti-gay-marriage Proposition 8, which parallels the anti-gay rights Proposition 6 that is explored in the film.[14]

Regardless, many reviewers and pundits have noted that the highly acclaimed film has taken on a new significance after the successful passage of Proposition 8 as a galvanizing point of honoring a major gay political and historical figure who would have strongly opposed the measure.[15][16] Activists called on Focus Features to pull the film from the Cinemark Theatres chain as part of a series of boycotts because Cinemark's chief executive, Alan Stock, donated $9,999 to the Yes on 8 campaign.[17][18]

In the United States, Milk was given a limited release on November 26, 2008, and expanded to additional theaters each of the following weekends to a maximum of 882 screens. The film made the top 10 box office list on its opening weekend with earnings of $1.4 million in 36 theaters.[19]. Milk will be released on DVD and Blu-ray on March 10, 2009.[20]

Critical reception

Milk received widespread acclaim from film critics.[21] As of January 30, 2009, Rotten Tomatoes has given the film a 93% rating with a 184 fresh and fourteen rotten reviews. The average score is 8/10.[22] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film has received an average score of 84, based on 38 reviews.[21]

Todd McCarthy of Variety called the film "adroitly and tenderly observed," "smartly handled," and "most notable for the surprising and entirely winning performance by Sean Penn." He added, "[W]hile Milk is unquestionably marked by many mandatory scenes . . . the quality of the writing, acting and directing generally invests them with the feel of real life and credible personal interchange, rather than of scripted stops along the way from aspiration to triumph to tragedy. And on a project whose greatest danger lay in its potential to come across as agenda-driven agitprop, the filmmakers have crucially infused the story with qualities in very short supply today - gentleness and a humane embrace of all its characters."[23]

Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter said the film "transcends any single genre as a very human document that touches first and foremost on the need to give people hope" and added it "is superbly crafted, covering huge amounts of time, people and the zeitgeist without a moment of lapsed energy or inattention to detail . . . Black's screenplay is based solely on his own original research and interviews, and it shows: The film is richly flavored with anecdotal incidents and details. Milk surfaces in a season filled with movies based on real lives, but this is the first one that inspires a sense of intimacy with its subjects."[24]

A.O. Scott of The New York Times called Milk, "A Marvel", and wrote the film "is a fascinating, multi-layered history lesson. In its scale and visual variety it feels almost like a calmed-down Oliver Stone movie, stripped of hyperbole and Oedipal melodrama. But it is also a film that like Mr. Van Sant’s other recent work — and also, curiously, like David Fincher’s Zodiac, another San Francisco-based tale of the 1970s — respects the limits of psychological and sociological explanation."[25]

Christianity Today, a major progressive Christian-faith based periodical, gave the film a positive response.[15] It stated that "Milk achieves what it sets out to do, telling an inspiring tale of one man's quest to legitimize his identity, to give hope to his community. I'm not sure how well it'll play outside of big cities, or if it will sway any opinions on hot-button political issues, but it gives a valiant, empathetic go of it." It also stated that the portrayal of Dan White was very fair and humanized and portrayed as more of a flawed and tragically opinionated character, rather than a "typical 'crazy Christian villain' stereotype".[15] That was often shown in many gay themed films.

In contrast, John Podhoretz of the neoconservative magazine Weekly Standard blasted the portrayal of Harvey Milk, saying that it treated the "smart, aggressive, purposefully offensive, press-savvy" activist like a "teddy bear". Podhoretz also argued that the film glosses over Milk's polyamorous relationships; he opined that this contrasts Milk from present day gay rights activists fighting over monogamous same-sex marriage.[26]

Screenwriter and journalist Richard David Boyle, who described himself as a former political ally of Milk's, stated that the film made a creditable effort of recreating the era. He also wrote that Penn captured Milk's "smile and humanity", and his sense of humor about his homosexuality. Boyle reserved criticism for what he felt was the film's inability to tell the whole story of Milk's election and demise.[27]

The Advocate, while supporting the film in general, criticized the choice of Penn given the actor's support for the government of Cuba despite the country's anti-gay rights record.[28] Human Rights Foundation president Thor Halvorssen said in the article "that Sean Penn would be honored by anyone, let alone the gay community, for having stood by a dictator that put gays into concentration camps is mind-boggling."[28] Los Angeles Times film critic Patrick Goldstein commented in response to the controversy, "I'm not holding my breath that anyone will be holding Penn's feet to the fire."[28]

Top ten lists

The film appeared on many critics' top ten lists of the best films of 2008.[29] Movie City News shows that the film appeared in 131 different top ten lists, out of 286 different critics lists surveyed, the 4th most mentions on a top ten list of the films released in 2008.[30]

Awards and nominations

Milk had received accolades from several film critics organizations. On December 9, the film received eight Critic's Choice Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director. Two days later, Sean Penn received one Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor, the film's only nomination. On December 18, the Screen Actors Guild nominated Milk on three categories: Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor and Best Cast in a Motion Picture for the 15th Screen Actors Guild Awards; Sean Penn was chosen as Best Actor. On January 5th, the film's producers received a nomination for Producer of the Year for the 20th Producers Guild of America Awards; and on January 8th Gus Van Sant received a nomination for Outstanding Directorial Achievement for the 61st Directors Guild of America Awards. The film won Best Original Screenplay at the 62nd Writers Guild of America Awards and received four BAFTA award nominations, including Best Film, for the 62nd British Academy Film Awards. On January 22, 2009; Milk received 8 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, for the 81st Academy Awards, winning two for Best Original Screenplay and Best Actor in a Leading Role (Sean Penn).

| List of awards and nominations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- ^ Edelstein D. "http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=97518380 'Milk' Is Much More Than A Martyr Movie." NPR. November 26, 2008. Accessed on: January 3, 2009.

- ^ Stephen Talbot (1991). "Sixties something". Mother Jones. 16 (2): 47–9, 69–70.

- ^ Barry Koltnow (December 4, 2008). "Orange County plays the villain in Harvey Milk movie". Orange County Register. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ Toumarkine, Doris (July 15, 1992). "Van Sant set for Milk biopic". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (April 19, 1993). "Van Sant off of 'Castro St.'". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (April 12, 2007). "Dueling directors Milk a good story". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Goldstein, Gregg (September 10, 2007). "Van Sant closes in on Milk tale". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg (November 17, 2007). "Van Sant's 'Milk' a go for Jan". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Garrett, Diane (November 18, 2007). "Van Sant's 'Milk' pours first". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg (December 5, 2007). "Hirsch, Franco, Brolin got 'Milk'". The Hollywood Reporter.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Garrett, Diane (December 4, 2007). "Josh Brolin circles 'Milk' killer". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Kit, Borys (February 1, 2008). "'Milk' shoot does the Castro good". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (March 18, 2008). "It's a wrap - 'Milk' filming ends in S.F." San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (October 28, 2008). "Politics? Focus won't 'Milk' it". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ a b c "Milk". Christianity Today. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lim, Dennis (November 26, 2008). "Harvey Would Have Opened It in October". Slate.com.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|title= - ^ Abramowitz, Rachel (November 25, 2008). "L.A. Film Festival director Richard Raddon resigns". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ "No MILK for Cinemark!". nomilkforcinemark.com. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ http://www.boxofficeprophets.com/column/index.cfm?columnID=11142&cmin=10&columnpage=3%7CBox Office Prophets

- ^ Milk DVD Release

- ^ a b "Milk (2008): Reviews". Metacritic. CNET Networks, Inc. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- ^ "Milk Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 2, 2008). "Review of Milk". Variety. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (November 2, 2008). "Film Review: Milk". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ A.O. Scott (2008-11-26). "Movie Review - Milk". The New York Times.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Rose-Colored Milk. By John Podhoretz. Weekly Standard. Published December 6, 2008. Accessed December 12, 2008.

- ^ Boyle, Richard David, Local writer tells inside story of "Milk", Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, December 17, 2008

- ^ a b c Goldstein, Patrick (December 11, 2008). "'Milk' star Sean Penn: Pal of anti-gay dictators?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "Metacritic: 2008 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ David Poland (2008). "The 2008 Movie City News Top Ten Awards". Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ [1]

- ^ ACE Eddie Awards

- ^ American Film Institute

- ^ Art Directors Guild Awards

- ^ Austin Film Critics Awards

- ^ Boston Society of Film Critics Awards

- ^ BFCA Critic's Choice Awards

- ^ BAFTA Awards

- ^ Chicago Film Critics Association Awards

- ^ Costume Designers Guild Awards

- ^ Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards

- ^ Detroit Film Critics Awards

- ^ DGA Awards

- ^ GLAAD Media Awards

- ^ Golden Globe Awards

- ^ Houston Film Critics Awards

- ^ Independent Spirit Awards

- ^ IFMCA Awards

- ^ London Film Critics Circle Awards

- ^ Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards

- ^ MPSE Golden Reel Awards

- ^ National Board of Review

- ^ National Society of Film Critics

- ^ New York Film Critics Awards

- ^ New York Film Critics Online

- ^ Oklahoma Film Critics

- ^ Phoenix Film Critics Awards

- ^ PGA Stanley Kramer Award

- ^ PGA Awards

- ^ St. Louis Film Critics Awards

- ^ San Francisco Film Critics Awards

- ^ Satellite Awards

- ^ SAG Awards

- ^ Society of Camera Operators

- ^ Southeastern Film Critics

- ^ Toronto Film Critics

- ^ Vancouver Film Critics

- ^ Washington DC Area Film Critics Awards

- ^ WGA Awards

External links

- 2008 films

- 2000s drama films

- American drama films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Gus Van Sant

- Biographical films

- Films based on actual events

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films about elections

- Films set in the 1970s

- LGBT-related films

- Political drama films

- Films shot in Super 35

- Focus Features films

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award winning performance

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award