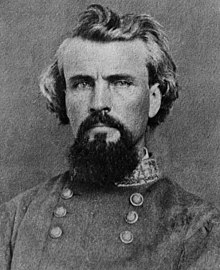

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Old Bed[1] Devil Forrest[2] Wizard of the Saddle[1] |

| Born | July 13, 1821 Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | October 29, 1877 (aged 56) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | White's Company, TN Mounted Rifles |

| Commands | 3rd Tennessee Cavalry Forrest's Cavalry Brigade Forrest's Cavalry Division Forrest's Cavalry Corps |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Relations | |

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 – October 29, 1877), called Bedford Forrest in his lifetime, was a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.

A cavalry and military commander in the war, Forrest is one of the war's most unusual figures. Although less educated than many of his fellow officers, before the war Forrest had already amassed a fortune as a planter, real estate investor, and slave trader. He was one of the few officers in either army to enlist as a private and be promoted to general officer and corps commander during the war. He created and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname The Wizard of the Saddle.[3] In their postwar writings, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee both expressed their belief that the Confederate high command had failed to fully use Forrest's talents.[4]

Ulysses S. Grant called him "that devil Forrest." Another Union general, William Tecumseh Sherman, it is reported, considered him "the most remarkable man our civil war produced on either side." He was unquestionably one of the Civil War's most brilliant tacticians. Without military education or training, he became the scourge of Grant, Sherman, and almost every other Union general who fought in Tennessee, Alabama, or Kentucky. Forrest fought by simple rules: he maintained that "war means fighting and fighting means killing" and that the way to win was "to get there first with the most men." His cavalry, which Sherman reported in disgust "could travel one hundred miles in less time it takes ours to travel ten," secured more Union guns, horses, and supplies than any other single Confederate unit. He played pivotal roles at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, the capture of Murfreesboro, the Franklin-Nashville campaign, Brice's Cross Roads, and in pursuit and capture of Streight's Raiders.[5]

Forrest was accused of war crimes at the Battle of Fort Pillow for allegedly allowing forces under his command to massacre hundreds of black Union Army and white Southern Unionist prisoners. However, Sherman investigated the allegations and did not charge Forrest with any improprieties. Park Ranger Matt Atkinson, during his lecture on Brice's Crossroads, stated that there were no orders found in the chain of command, ordering the massacre of the garrison.[6]

He was a pledged delegate from Tennessee to the New York Democratic national convention of 4 July 1868. Forrest was an early member of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Historian and Forrest biographer Brian Steel Wills writes, "While there is no doubt that Forrest joined the Klan, there is some question as to whether he actually was the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.[7]

Early life

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born to a poor Scotch-Irish American family in Bedford County, Tennessee. He and his twin sister, Fanny, were the two eldest of blacksmith William Forrest's 12 children with wife Miriam Beck. The Forrest family had migrated to Tennessee from Virginia, via North Carolina, during the second half of the 18th century, while the Beck family had moved from South Carolina to Tennessee around the same time.[8] After the deaths of his father and Fanny to scarlet fever, Forrest at age 17 became head of the family.

In 1841, Forrest went into business with his uncle Jonathan Forrest in Hernando, Mississippi. His uncle was killed there in 1845 during an argument with the Matlock brothers. In retaliation, Forrest shot and killed two of them with his two-shot pistol and wounded two others with a knife which had been thrown to him. One of the wounded Matlock men survived and served under Forrest during the Civil War.[9]

Forrest became a businessman, planter, and slaveholder. He owned several cotton plantations in the Delta region of West Tennessee. He was also a slave trader, at a time when demand was booming in the Deep South; he had his trading business based on Adams Street in Memphis. In 1858, Forrest (a Democrat), was elected a Memphis city alderman.[10] Forrest supported his mother and put his younger brothers through college. By the time the American Civil War started in 1861, he had become a millionaire and one of the richest men in the South, having amassed a "personal fortune that he claimed was worth $1.5 million".[11]

Before the Civil War, Forrest was well known as a Memphis speculator and Mississippi gambler. He was for some time captain of a boat which ran between Memphis, Tennessee and Vicksburg, Mississippi. As his fortune increased he engaged in plantation speculation, and became the nominal owner of two plantations not far from Goodrich's Landing, above Vicksburg, where he worked some hundred or more slaves ... He was known to his acquaintances as a man of obscure origin and low associations, a shrewd speculator, negro trader, and duelist, but a man of great energy and brute courage.[12]

Marriage and family

In 1845, Nathan married Mary Ann Montgomery (1826–1893), the daughter of a Presbyterian minister. They had two children together: William Montgomery Bedford Forrest (1846–1908), who enlisted at the age of 15 and served alongside his father in the war, and a daughter Fanny (1849–1854), who died in childhood. His descendants continued the military tradition. A grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest II (1872–1931), became commander-in-chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. A great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III (1905–1943), graduated from West Point and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. Army Air Corps; he was killed during a bombing raid over Nazi Germany in 1943.

Forrest had 12 brothers and sisters, and half of them died of typhoid. Isaac and Bedford (twins), Fanny (Forrest's twin), Milly, Mary all died when Forrest was about 11. His father recovered but died from the effects five years later. So, he was 16, his brother John was 15, and then they went all the way down to 8 and under - Bill, Jesse, and Aaron with Jeffrey being born after. A few years later, Miriam remarried to John (sometimes James) Luxton, a marshal, and had three boys and a girl with him. At the outset of the Civil War, Forrest had a 10-year-old sister, the only one he had.[13]

Civil War

Early activities

After the Civil War broke out, Forrest returned to Tennessee from his Mississippi ventures, enlisted in the Confederate States Army (CSA), and trained at Fort Wright in Randolph, Tennessee.[14] On July 14, 1861, he joined Captain Josiah White's Company "", Tennessee Mounted Rifles as a private, along with his youngest brother and 15-year-old son. Upon seeing how badly equipped the CSA was, Forrest offered to buy horses and equipment with his own money for a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers.[15][16]

His superior officers and the state Governor Isham G. Harris were surprised that someone of Forrest's wealth and prominence had enlisted as a soldier, especially since major planters were exempted from service. They commissioned him as a lieutenant colonel and authorized him to recruit and train a battalion of Confederate mounted rangers. In October 1861, Forrest was given command of a regiment, the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry. Though Forrest had no prior formal military training or experience, he had exhibited leadership, and soon proved he had a gift for successful tactics.

Public debate surrounded Tennessee's decision to join the Confederacy. Both the CSA and the Union armies recruited soldiers from the state. More than 100,000 men from Tennessee served with the Confederacy (more per capita than any other state), and 50,000 served with the Union.[17] Forrest posted ads to join his regiment for "men with good horse and good gun" adding "if you wanna have some fun and to kill some Yankees".[18]

At six feet, two inches (1.88 m) tall and 210 pounds (95 kg; 15 stone), Forrest was physically imposing and intimidating, especially compared to the average height of men at the time. He used his skills as a hard rider and fierce swordsman to great effect; he was known to sharpen both the top and bottom edges of his heavy saber.

Historians have evaluated contemporary records to conclude that Forrest may have killed more than 30 enemy soldiers[19] with saber, pistol, and shotgun. Not all of Forrest's feats of individual combat involved enemy troops. Lt. A. Wills Gould, an artillery officer in Forrest's command, was being transferred, presumably because cannons under his command were spiked by the enemy during the Battle of Day's Gap.[20] On June 14, 1863, Gould confronted Forrest about his transfer, which escalated into a violent exchange. Gould shot Forrest in the hip; Forrest mortally stabbed Gould.

Forrest's command included his Escort Company (his "Special Forces"), for which he selected the best soldiers available. This unit, which varied in size from 40 to 90 men, was the elite of the cavalry.

Cavalry command

Forrest received praise for his skill and courage during an early victory in the Battle of Sacramento in Kentucky, where he routed a Union force by personally leading a cavalry charge that was later commended by his commander, Brigadier General Charles Clark.[21] Forrest distinguished himself further at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862. After his cavalry captured a Union artillery battery, he broke out of a Union Army siege headed by Major General Ulysses S. Grant. Forrest rallied nearly 4,000 troops and led them across the river.

A few days after Fort Donelson, with the fall of Nashville to Union forces imminent, Forrest took command of the city. Local industries had several millions of dollars worth of heavy ordnance machinery. Forrest arranged for transport of the machinery and several important government officials to safe locations.[22]

A month later, Forrest was back in action at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862). He commanded a Confederate rear guard after the Union victory. In the battle of Fallen Timbers, he drove through the Union skirmish line. Not realizing that the rest of his men had halted their charge when reaching the full Union brigade, Forrest charged the brigade single-handedly, and soon found himself surrounded. He emptied his Colt Army revolvers into the swirling mass of Union soldiers and pulled out his saber, hacking and slashing. A Union infantryman on the ground beside him fired a musket ball into Forrest's spine with a point-blank musket shot, nearly knocking him out of the saddle. The ball went through his pelvis and lodged near his spine. Steadying himself and his mount, he used one arm to lift the Union soldier by the shirt collar and then wielded him as a human shield before casting his body aside after he had found his way to safety. Forrest is acknowledged to have been the last man wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.[23] Forrest galloped back to his incredulous troopers.[24] A surgeon removed the musket ball a week later, without anesthesia, which was unavailable. Forrest would likely have been given a generous dose of alcohol to muffle the pain of the surgery.[25]

By early summer, Forrest commanded a new brigade of "green" cavalry regiments. In July, he led them into Middle Tennessee under orders to launch a cavalry raid. On July 13, 1862, he led them into the First Battle of Murfreesboro, which Forrest is said to have won.[26]

According to a report by a Union commander:

The forces attacking my camp were the First Regiment Texas Rangers [8th Texas Cavalry, Terry's Texas Rangers, ed.], Colonel Wharton, and a battalion of the First Georgia Rangers, Colonel Morrison, and a large number of citizens of Rutherford County, many of whom had recently taken the oath of allegiance to the United States Government. There were also quite a number of negroes attached to the Texas and Georgia troops, who were armed and equipped, and took part in the several engagements with my forces during the day.[27]

Promoted in July 1862 to brigadier general, Forrest was given command of a Confederate cavalry brigade.[28] In December 1862, Forrest's veteran troopers were reassigned by Gen. Braxton Bragg to another officer, against his protest. Forrest had to recruit a new brigade, composed of about 2,000 inexperienced recruits, most of whom lacked weapons. Again, Bragg ordered a raid, this one into west Tennessee to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under Grant, which were threatening the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Forrest protested that to send such untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. On the ensuing raid, he showed his brilliance, leading thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a "wild goose chase" to try to locate his fast-moving forces. Never staying in one place long enough to be attacked, Forrest led his troops in raids as far north as the banks of the Ohio River in southwest Kentucky. He returned to his base in Mississippi with more men than he had started with. By then, all were fully armed with captured Union weapons. As a result, General Grant was forced to revise and delay the strategy of his Vicksburg campaign. "He [Forrest] was the only Confederate cavalryman of whom Grant stood in much dread," a friend of Ulysses was quoted as saying.[29]

The Union Army occupied Tennessee in 1862 and for the duration of the war, taking control of strategic cities and railroads. Forrest continued to lead his men in small-scale operations until April 1863. The Confederate army dispatched him with a small force into the backcountry of northern Alabama and west Georgia to defend against an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen commanded by Colonel Abel Streight. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, to cut off Bragg's supply line and force him to retreat into Georgia. Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way. Streight's goal changed to escape the pursuit. On May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight's unit east of Cedar Bluff, Alabama. Forrest had fewer men than the Union side, but he repeatedly paraded some of them around a hilltop to appear a larger force, and convinced Streight to surrender his 1,500 exhausted troops.[30]

Forrest served with the main army at the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18 to 20, 1863). He pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners.[31] Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, upon which Forrest was quoted as saying, "What does he fight battles for?" [32] The story that Forrest confronted and threatened the life of Bragg in the fall of 1863, following the battle of Chickamauga, and that Bragg transferred Forrest to command in Mississippi as a direct result, is now considered to be apocryphal and the invention of Dr. J. B. Cowan.[33][34] On December 4, 1863, Forrest was promoted to the rank of major general.[35]

On March 25, 1864, Forrest was at Paducah, Kentucky where he unsuccessfully demanded surrender of U.S. Col. Stephen G. Hicks:

... if I have to storm your works, you may expect no quarter.[36]

Fort Pillow

On April 12, 1864, General Forrest led his forces in the attack and capture of Fort Pillow, in Henning, Tennessee, on the Mississippi River. Many African American Union soldiers were killed in the battle. A controversy arose May 3, 1864 about whether Forrest conducted or condoned a massacre of negro soldiers, white Tennessee Unionists, and Confederate deserters, who had surrendered there. President Abraham Lincoln asked his cabinet for opinions as to how the Union should respond to the massacre.[37]

According to reports filed by Union Captain Goodman, Union forces never surrendered; he said it was agreed that if the fort was surrendered, the whole garrison, white and black, would be treated as prisoners of war. General Forrest sent additional communiques to Major Lionel F. Booth demanding total surrender, but Major Booth had been fatally shot in the battle and the command of Fort Pillow had already been assumed by Major William F. Bradford. The delayed reply to Forrest's demands bore the name of Major Booth, asking for more time to decide about surrendering the fort and the gunboat Olive Branch. General Forrest replied that the gunboat was not expected to be surrendered, but the fort alone. Hours later during the truce, after many communiques, the Union sent their answer, "a brief but positive refusal to capitulate".[38]

Forrest's men insisted that the Union soldiers, although fleeing, kept their weapons and frequently turned to shoot, forcing the Confederates to keep firing in self defense.[39] Confederates said the Union flag was still flying over the fort, which indicated that the force had not formally surrendered. A contemporary newspaper account from Jackson, Tennessee, stated that "General Forrest begged them to surrender", but "not the first sign of surrender was ever given." Similar accounts were reported in many Southern newspapers at the time.[40]

These statements, however, were contradicted by Union survivors, as well as the letter of a Confederate soldier who graphically recounted a massacre. Achilles Clark, a soldier with the 20th Tennessee cavalry, wrote to his sister immediately after the battle:

The slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor, deluded, negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees, and with uplifted hands scream for mercy, but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. I, with several others, tried to stop the butchery, and at one time had partially succeeded, but General Forrest ordered them shot down like dogs and the carnage continued. Finally our men became sick of blood and the firing ceased.[41]

Ulysses S. Grant, in his Personal Memoirs, says of the battle:

These troops fought bravely, but were overpowered. I will leave Forrest in his dispatches to tell what he did with them. 'The river was dyed,' he says, 'with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed, but few of the officers escaping. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.' Subsequently Forrest made a report in which he left out the part which shocks humanity to read.[42]

At the time of the massacre General Grant was no longer in Tennessee but had transferred to the east to command all Union troops.[43] Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, Commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, which included Tennessee, wrote:

The massacre at Fort Pillow occurred April 12, 1864, and has been the subject of congressional inquiry.[44] No doubt Forrest's men acted like a set of barbarians, shooting down the helpless negro garrison after the fort was in their possession; but I am told that Forrest personally disclaims any active participation in the assault, and that he stopped the firing as soon as he could. I also take it for granted that Forrest did not lead the assault in person, and consequently that he was to the rear, out of sight if not of hearing at the time, and I was told by hundreds of our men, who were at various times prisoners in Forrest's possession, that he was usually very kind to them. He had a desperate set of fellows under him, and at that very time there is no doubt the feeling of the Southern people was fearfully savage on this very point of our making soldiers out of their late slaves, and Forrest may have shared the feeling.[45]

Historians have differed on interpretation of events. Richard Fuchs, author of An Unerring Fire, concludes:

The affair at Fort Pillow was simply an orgy of death, a mass lynching to satisfy the basest of conduct – intentional murder – for the vilest of reasons – racism and personal enmity.[46]

Andrew Ward downplays the controversy:

Whether the massacre was premeditated or spontaneous does not address the more fundamental question of whether a massacre took place... it certainly did, in every dictionary sense of the word.[47]

John Cimprich states:

The new paradigm in social attitudes and the fuller use of available evidence has favored a massacre interpretation... Debate over the memory of this incident formed a part of sectional and racial conflicts for many years after the war, but the reinterpretation of the event during the last thirty years offers some hope that society can move beyond past intolerance.[48]

The site is now a State Historic Park.

Brice's Crossroads

Forrest's greatest victory came on June 10, 1864, when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,500 men commanded by Union Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads. Here, his mobility of force and superior tactics led to victory. He swept the Union forces from a large expanse of southwest Tennessee and northern Mississippi. Forrest set up a position for an attack to repulse a pursuing force commanded by Sturgis, who had been sent to impede Forrest from destroying Union supplies and fortifications. When Sturgis's Federal army came upon the crossroad, they collided with Forrest's cavalry.[49] Sturgis ordered his infantry to advance to the front line to counteract the cavalry. The infantry, tired and weary and suffering under the heat, were quickly broken and sent into mass retreat. Forrest sent a full charge after the retreating army and captured 16 artillery pieces, 176 wagons, and 1,500 stands of small arms. In all, the maneuver cost Forrest 96 men killed and 396 wounded. The day was worse for Union troops, which suffered 223 killed, 394 wounded, and 1,623 men missing. The losses were a deep blow to the black regiment under Sturgis's command. In the hasty retreat, they stripped off commemorative badges that read "Remember Fort Pillow", to avoid goading the Confederate force pursuing them.[50]

Conclusion of the war

One month later, while serving under General Stephen D. Lee, Forrest experienced tactical defeat at the Battle of Tupelo in 1864. Concerned about Union supply lines, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman sent a force under the command of Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith to deal with Forrest. The Union forces drove the Confederates from the field and Forrest was wounded in the foot, but his forces were not wholly destroyed. He continued to oppose Union efforts in the West for the remainder of the war.

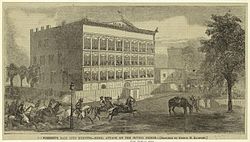

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown Memphis in August 1864 (the Second Battle of Memphis), and another on a Union supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee, on November 4–5, 1864 (the Battle of Johnsonville), causing millions of dollars in damage. In December, during Hood's Tennessee Campaign, he fought alongside General John Bell Hood, the newest (and last) commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in the Second Battle of Franklin. Facing a disastrous defeat, Forrest argued bitterly with Hood (his superior officer) demanding permission to cross the river and cut off the escape route of Union Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield's army. He made the belated attempt, but it was too late.

After his bloody defeat at Franklin, Hood continued to Nashville. Hood ordered Forrest to conduct an independent raid against the Murfreesboro garrison. After success in achieving the objectives specified by Gen. Hood, Forrest engaged Union forces near Murfreesboro on December 5, 1864. In what would be known as the Third Battle of Murfreesboro, a portion of Forrest's command broke and ran. After Hood's Army of Tennessee was all but destroyed at the Battle of Nashville, Forrest distinguished himself by commanding the Confederate rear guard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape. For this, he earned promotion to the rank of lieutenant general. A portion of his command, now dismounted, was surprised and captured in their camp at Verona, Mississippi, on December 25, 1864, during a raid of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad by a brigade of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson's cavalry division.

In 1865, Forrest attempted, without success, to defend the state of Alabama against Wilson's raid. His opponent, Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, defeated Forrest at the Battle of Selma, April 2, 1865. When he received news of Lee's surrender, Forrest also chose to surrender. On May 9, 1865, at Gainesville, Forrest read his farewell address.

Forrest's farewell address to his troops, May 9, 1865

The following text is excerpted from Forrest's farewell address to his troops:

Civil war, such as you have just passed through naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings; and as far as it is in our power to do so, to cultivate friendly feelings towards those with whom we have so long contended, and heretofore so widely, but honestly, differed. Neighborhood feuds, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out; and, when you return home, a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to Government, to society, or to individuals meet them like men.

The attempt made to establish a separate and independent Confederation has failed; but the consciousness of having done your duty faithfully, and to the end, will, in some measure, repay for the hardships you have undergone. In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. Without, in any way, referring to the merits of the Cause in which we have been engaged, your courage and determination, as exhibited on many hard-fought fields, has elicited the respect and admiration of friend and foe. And I now cheerfully and gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the officers and men of my command whose zeal, fidelity and unflinching bravery have been the great source of my past success in arms.

I have never, on the field of battle, sent you where I was unwilling to go myself; nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the Government to which you have surrendered can afford to be, and will be, magnanimous.— N.B. Forrest, Lieut.-General

Headquarters, Forrest's Cavalry Corps

Gainesville, Alabama

May 9, 1865[51]

Forrest's military doctrines

Forrest grasped the doctrines of "mobile warfare"[52] that became prevalent in the 20th century. Paramount in his strategy was fast movement, even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, which he did more than once. Noted Civil War scholar Bruce Catton writes:

Forrest ... used his horsemen as a modern general would use motorized infantry. He liked horses because he liked fast movement, and his mounted men could get from here to there much faster than any infantry could; but when they reached the field they usually tied their horses to trees and fought on foot, and they were as good as the very best infantry.[53]

Forrest is often erroneously quoted as saying his strategy was to "git thar fustest with the mostest." Now often recast as "Getting there firstest with the mostest",[54] this misquote first appeared in print in a New York Tribune article written to provide colorful comments in reaction to European interest in Civil War generals. The aphorism was addressed and corrected by a New York Times story in 1918 to be: "Ma'am, I got there first with the most men."[55] Though a novel and succinct condensation of the military principles of mass and maneuver, Bruce Catton writes:

Do not, under any circumstances whatever, quote Forrest as saying 'fustest' and 'mostest'. He did not say it that way, and nobody who knows anything about him imagines that he did.[56]

Forrest became well known for his early use of "maneuver" tactics as applied to a mobile horse cavalry deployment.[57] He sought to constantly harass the enemy in fast-moving raids, and to disrupt supply trains and enemy communications by destroying railroad track and cutting telegraph lines, as he wheeled around the Union Army's flank.

War record and promotions

- Enlisted as Private July 1861. (White's Company "E", Tennessee Mounted Rifles)

- Commissioned as lieutenant colonel, October 1861 (3rd Tennessee Cavalry)

- Promoted to colonel, February 1862, Battle of Fort Donelson

- Wounded, Battle of Shiloh, April 1862

- Promoted to brigadier general, July 21, 1862

- First Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862

- Raids in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi, Early December 1862 – Early January 1863

- Battle of Day's Gap, April–May 1863

- Assigned to command Forrest's Cavalry Corps, May 1863

- Battle of Chickamauga, September 1863

- Promoted major general, December 4, 1863

- Battle of Paducah, March 1864

- Battle of Fort Pillow, April 1864

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads, June 1864

- Battle of Tupelo, July 14–15, 1864

- Raids in Tennessee, August–October 1864

- Battle of Spring Hill, November 29, 1864

- Battle of Franklin, November 30, 1864

- Third Battle of Murfreesboro, December 5–7, 1864

- Battle of Nashville, December 15–16, 1864

- Promoted to lieutenant general, February 28, 1865[28]

- Battle of Selma, April 2, 1865

- Final Address to his troops, May 9, 1865

Postwar years

This article possibly contains original research. (November 2007) |

Business ventures

With slavery abolished after the war, Forrest suffered a major financial setback as a former slave trader. He became interested in the area around Crowley's Ridge during the war and settled in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1866 Forrest and C. C. McCreanor contracted to finish the Memphis & Little Rock Railroad. He built a commissary in a town forming along the rail route which most residents were calling "Forrest's Town," incorporated as Forrest City, Arkansas in 1870.

He later found employment at the Selma-based Marion & Memphis Railroad and eventually became the company president. He was not as successful in railroad promoting as in war, and under his direction, the company went bankrupt. Nearly ruined as the result of the failure of the Marion & Memphis, Forrest spent his final days running a prison work farm on President's Island in the Mississippi River. Forrest's health was in steady decline. He and his wife lived in a log cabin they had salvaged from his plantation.

Offers services to Sherman

During the Virginius Affair of 1873, some of Forrest's old Southern friends were filibusterers aboard the vessel so he wrote a letter to then General-in-Chief of the United States Army William Tecumseh Sherman and offered his services in case of war with Spain. Sherman, who in the Civil War had recognized what a deadly foe Forrest was, replied after the crisis settled down. He thanked Forrest for the offer and stated that had war broken out, he would have considered it an honor to have served side-by-side with him.[58]

Ku Klux Klan membership

Klan membership

Forrest was an early member of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Historian and Forrest biographer Brian Steel Wills writes, "While there is no doubt that Forrest joined the Klan, there is some question as to whether he actually was the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan."[59] The KKK (the Klan) was formed by veterans of the Confederate Army in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1866 and soon expanded throughout the state and beyond. Forrest became involved sometime in late 1866 or early 1867. A common report is that Forrest arrived in Nashville in April 1867 while the Klan was meeting at the Maxwell House Hotel, probably at the encouragement of a state Klan leader, former Confederate general George Gordon. The organization had grown to the point where an experienced commander was needed, and Forrest fit the bill. In Room 10 of the Maxwell, Forrest was sworn in as a member.[60] The title Grand Wizard was chosen because general Forrest was known as the wizard of the saddle during the civil war.[61]

After the Civil War had ended, the United States Congress began passing the Reconstruction Acts to lay out requirements for the former Confederate States to be re-admitted to the Union, to include ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. One of its stipulations was specifically granting voting rights to black men. According to Wills, in the August 1867 state elections the Klan was relatively restrained in its actions. White Americans who made up the KKK hoped to persuade black voters that a return to their prewar state of bondage was in their best interest. Forrest assisted in maintaining order. It was after these efforts failed that Klan violence and intimidation escalated and became widespread.[62] Author Andrew Ward, however, writes, "In the spring of 1867, Forrest and his dragoons launched a campaign of midnight parades; 'ghost' masquerades; and 'whipping' and even 'killing Negro voters and white Republicans, to scare blacks off voting and running for office.'"[63]

In an 1868 interview by a Cincinnati newspaper, Forrest claimed that the Klan had 40,000 members in Tennessee and 550,000 total members throughout the Southern states. He said he sympathized with them, but denied any formal connection. He claimed he could muster thousands of men himself. He described the Klan as "a protective political military organization... The members are sworn to recognize the government of the United States... Its objects originally were protection against Loyal Leagues and the Grand Army of the Republic..." After only a year as Grand Wizard, in January 1869, faced with an ungovernable membership employing methods that seemed increasingly counterproductive, Forrest issued KKK General Order Number One: “It is therefore ordered and decreed, that the masks and costumes of this Order be entirely abolished and destroyed.” [64]

In August 1874, Forrest “volunteered to help ‘exterminate’ those men responsible for the continued violence against the blacks.” After the murder of four blacks by a lynch mob after they were arrested for defending themselves at a BBQ, Forrest wrote to Tennessee Governor Brown, offering “to exterminate the white marauders who disgrace their race by this cowardly murder of Negroes.” [65]

By the end of his life, Forrest’s racial attitudes would evolve — in 1875, he advocated for the admission of blacks into law school — and he lived to fully renounce his involvement with the Klan that he headed and abolished.

Congressional testimony

Forrest testified before the Congressional investigation on Klan activities on June 27, 1871. Forrest denied membership, but his individual role in the KKK was beyond the scope of the investigating committee which wrote:

- "When it is considered that the origin, designs, mysteries, and ritual of the order are made secrets; that the assumption of its regalia or the revelation of any of its secrets, even by an expelled member, or of its purposes by a member, will be visited by 'the extreme penalty of the law,' the difficulty of procuring testimony upon this point may be appreciated, and the denials of the purposes, of membership in, and even the existence of the order, should all be considered in the light of these provisions. This contrast might be pursued further, but our design is not to connect General Forrest with this order, (the reader may form his own conclusion upon this question,) but to trace its development, and from its acts and consequences gather the designs which are locked up under such penalties."[66]

The committee also noted, "The natural tendency of all such organizations is to violence and crime; hence it was that General Forrest and other men of influence in the state, by the exercise of their moral power, induced them to disband."[67]

Speaks to black Southerners

In July 1875, Forrest demonstrated that his personal sentiments on the issue of race now differed from those of the Klan, when he was invited to give a speech before an organization of black Southerners advocating racial reconciliation, called the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association. At this, his last public appearance, he made what the New York Times described as a "friendly speech"[12] during which, when offered a bouquet of flowers by a black woman, he accepted them as a token of reconciliation between the races and espoused a radical agenda (for the time) of equality and harmony between black and white Americans.[68] His speech was as follows:

- "Ladies and Gentlemen I accept the flowers as a memento of reconciliation between the white and colored races of the southern states. I accept it more particularly as it comes from a colored lady, for if there is any one on God's earth who loves the ladies I believe it is myself. (Immense applause and laughter.) This day is a day that is proud to me, having occupied the position that I did for the past twelve years, and been misunderstood by your race. This is the first opportunity I have had during that time to say that I am your friend. I am here a representative of the southern people, one more slandered and maligned than any man in the nation.

- I will say to you and to the colored race that men who bore arms and followed the flag of the Confederacy are, with very few exceptions, your friends. I have an opportunity of saying what I have always felt – that I am your friend, for my interests are your interests, and your interests are my interests. We were born on the same soil, breathe the same air, and live in the same land. Why, then, can we not live as brothers? I will say that when the war broke out I felt it my duty to stand by my people. When the time came I did the best I could, and I don't believe I flickered. I came here with the jeers of some white people, who think that I am doing wrong. I believe that I can exert some influence, and do much to assist the people in strengthening fraternal relations, and shall do all in my power to bring about peace. It has always been my motto to elevate every man- to depress none. (Applause.) I want to elevate you to take positions in law offices, in stores, on farms, and wherever you are capable of going.

- I have not said anything about politics today. I don't propose to say anything about politics. You have a right to elect whom you please; vote for the man you think best, and I think, when that is done, that you and I are freemen. Do as you consider right and honest in electing men for office. I did not come here to make you a long speech, although invited to do so by you. I am not much of a speaker, and my business prevented me from preparing myself. I came to meet you as friends, and welcome you to the white people. I want you to come nearer to us. When I can serve you I will do so. We have but one flag, one country; let us stand together. We may differ in color, but not in sentiment. Use your best judgement in selecting men for office and vote as you think right.

- Many things have been said about me which are wrong, and which white and black persons here, who stood by me through the war, can contradict. I have been in the heat of battle when colored men, asked me to protect them. I have placed myself between them and the bullets of my men, and told them they should be kept unharmed. Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I'll come to your relief. I thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for this opportunity you have afforded me to be with you, and to assure you that I am with you in heart and in hand." (Prolonged applause.)

In response to that Pole-Bearers speech, the Cavalry Survivors Association of Augusta, the first Confederate organization formed after the war, called a meeting in which Captain F. Edgeworth Eve gave a speech expressing unmitigated disapproval of Forrest's remarks promoting inter-ethnic harmony, by ridiculing his faculties and judgement and berating the woman who gifted Forrest flowers as "a mulatto wench". The association voted unanimously to amend its constitution to expressly forbid publicly advocating for or hinting at any association of white women and girls as being in the same classes as "females of the negro race".[69][70] The Macon Weekly Telegraph newspaper also condemned Forrest for his speech, describing the event as "the recent disgusting exhibition of himself at the negro [sic.] jamboree," and quoting part of a Charlotte, North Carolina Observer article which read "We have infinitely more respect for Longstreet, who fraternizes with negro men on public occasions, with the pay for the treason to his race in his pocket, than with Forrest and Pillow, who equalize with the negro women, with only 'futures' in payment."[71][72]

Death

Forrest died in Memphis in October 1877, at the home of his brother Jesse, reportedly from acute complications of diabetes.[73] His eulogy was delivered by his recent spiritual mentor and former Confederate chaplain, George Tucker Stainback, who declared in his eulogy: Lieutenant-General Nathan Bedford Forrest, though dead, yet speaketh. His acts have photographed themselves upon the hearts of thousands, and will speak there forever.[74]

Forrest was buried at Elmwood Cemetery.[73] In 1904 the remains of Forrest and his wife Mary were disinterred from Elmwood and moved to a Memphis city park originally named Forrest Park in his honor, that has since been renamed Health Sciences Park.[75]

On July 7, 2015, the Memphis City Council unanimously approved to move the remains of Nathan Bedford Forrest and his wife from Health Sciences Park. However, there are laws that protect him and his statue, the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013 and the U.S. Public Law 85-425: Sec. 410 approved May 23, 1958.[76]

Legacy

Many memorials were erected to Forrest in Tennessee, but only in Mississippi is there a county named after him. Obelisks in his memory were placed at his birthplace in Chapel Hill and at Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park near Camden. A statue of General Forrest was erected in Memphis's Forrest Park (renamed Health Sciences Park on February 5, 2013 amid great controversy).[77] A bust sculpted by Jane Baxendale is on display at the Tennessee State Capitol building in Nashville. The World War II Army base Camp Forrest in Tullahoma, Tennessee was named after him. It is now the site of the Arnold Engineering Development Center.

As of 2007[update], Tennessee had 32 dedicated historical markers linked to Nathan Bedford Forrest, more than are dedicated to the three former Presidents associated with the state: Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson (none of whom were born in Tennessee).[78] Finally, the Tennessee legislature established July 13 as "Nathan Bedford Forrest Day."[79]

A monument to Forrest in the Confederate Circle section of Old Live Oak Cemetery in Selma, Alabama, reads "Defender of Selma, Wizard of the Saddle, Untutored Genius, The first with the most. This monument stands as testament of our perpetual devotion and respect for Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest. CSA 1821–1877, one of the South's finest heroes. In honor of Gen. Forrest's unwavering defense of Selma, the great state of Alabama, and the Confederacy, this memorial is dedicated. DEO VINDICE." As armory for the Confederacy, Selma provided most of the South's ammunition. The bust of Forrest was stolen from the cemetery monument in March 2012 and efforts are currently underway to restore the monument.[80]

A monument to Forrest in the Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Rome, Georgia, was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1909 to honor his bravery for saving Rome from Union Army Colonel Abel Streight and his cavalry.

High schools named for Forrest were built in Chapel Hill, Tennessee, and Jacksonville, Florida. In 2008 the Duval County School Board voted 5–2 against a push to change the name of Nathan Bedford Forrest High School in Jacksonville.[81] In 2013, the board voted 7-0 to begin the process to rename the school.[81] The school was named for Forrest in 1959 at the urging of the Daughters of the Confederacy because they were upset about the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. At the time the school was all white, but now more than half the student body is black.[82] After several public forums and discussions, Westside High School was unanimously approved in January 2014 as the school's new name.

In August 2000, a road on Fort Bliss named for Forrest decades earlier was renamed for former post commander Richard T. Cassidy.[83][84][85]

In 2005, Shelby County Commissioner Walter Bailey started an effort to move the statue over Forrest's grave and rename Forrest Park. Former Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton, who is black, blocked the move. Others have tried to get a bust of Forrest removed from the Tennessee House of Representatives chamber.[86] Leaders in other localities have tried to remove or eliminate Forrest monuments, with mixed success.

The ROTC building at Middle Tennessee State University was named Forrest Hall in his honor. In 2006, the frieze depicting General Forrest on horseback that had adorned the side of this building was removed amid protests, but a major push to change its name failed. Also, the university's Blue Raiders' athletic mascot was changed to a pegasus from a cavalier, in order to avoid its mistaken association with General Forrest.

Forrest's great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III, pursued a military career, first in cavalry, then in aviation, and attained the rank of brigadier general in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. On June 13, 1943, Forrest III was killed in action while participating in a bombing raid over Germany, the first U.S. General to be killed in action in World War II. His family was awarded his Distinguished Service Cross (second only to the Medal of Honor) for staying with the controls of his B-17 bomber while his crew bailed out. The aircraft exploded before Forrest could bail out. By the time German air-sea rescue could arrive, only one of the crew was still alive in the water.

In popular culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

William Faulkner's 1943 short story "My Grandmother Millard and General Bedford Forrest and The Battle of Harrykin Creek" features Forrest as a character. Faulkner's 1938 novel "The Unvanquished" is set against the backdrop of Forrest's engagements with Union general Smith (presumably Andrew J. Smith).

"Bedford Forrest: Boy on Horseback" by Aileen Wells Parks in 1952 is part of the Childhood of Famous Americans series.

The 1987 novel Fightin' With Forrest tells the story of two young men who ride with Forrest during the War.[87]

In the 1990 PBS documentary The Civil War by Ken Burns, historian Shelby Foote states in Episode 7 that the Civil War produced two "authentic geniuses": Abraham Lincoln and Nathan Bedford Forrest; when expressing this opinion to one of General Forrest's granddaughters, she replied after a pause, "You know, we never thought much of Mr. Lincoln in my family."[88] Foote also used Forrest as a major character in his novel Shiloh which used numerous first-person stories to illustrate a detailed timeline and account of the battle.

Forrest appears in Harry Turtledove's 1992 alternate history/science fiction novel The Guns of the South. Forrest's great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III, appears in Turtledove's Settling Accounts novels.

In the 1994 film Forrest Gump, the titular character says that he was named after his ancestor General Nathan Bedford Forrest, who "... started up this club called the Ku Klux Klan." Tom Hanks who plays Gump, also makes a cameo as General Forrest, inserted into scenery from Birth of a Nation.

The children's science fiction series Animorphs has flashback scenes of an ancestor of one of the main characters fighting a battle against Forrest's brigade.

In the 2004 mockumentary C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America a slave narrator cites Nathan Bedford Forrest as the leader of a Confederate army that massacred hundreds of freed slaves in the North shortly after the Civil War, possibly an alternate reference to the Fort Pillow Massacre.

The 2006 song The Decline and Fall of Country and Western Civilization by Lambchop begins with the lines: "I hate Nathan Bedford Forrest / He's the featured artist in the Devil's chorus."

The song "Horse Soldier, Horse Soldier" from the 2007 album of the same name by Corb Lund and the Hurtin' Albertans references Forrest: "I's the firstest with the mostest when I fought for Bedford Forrest."

The Fort Pillow Massacre

There are conflicting reports about what occurred at Fort Pillow. Only 90 out of approximately 262 US Colored Troops survived the battle. Casualties were also high among white defenders of the fort, with 205 out of about 500 surviving. Forrest's Confederate forces were accused of subjecting captured soldiers to brutality, with allegations that some were burned to death. Forrest's men were alleged to have set fire to Union barracks with wounded Union soldiers inside; however, the report of Union Lieutenant Daniel Van Horn said that act was due to orders carried out by Union Lieutenant John D. Hill. Van Horn also reported that, "There never was a surrender of the fort, both officers and men declaring they never would surrender or ask for quarter."[89]

Following the cessation of hostilities, Forrest transferred the 14 most seriously wounded United States Colored Troops (USCT) to the U.S. Steamer Silver Cloud.[90] He sent 39 USCT taken as prisoners to higher command.[citation needed]

On October 30, 1877, The New York Times reported that "General Bedford Forrest, the great Confederate cavalry officer, died at 7:30 o'clock this evening at the residence of his brother, Colonel Jesse Forrest."

But The Times also reported that it would not be for military victories that Forrest would pass into history:

- "It is in connection with one of the most atrocious and cold-blooded massacres that ever disgraced civilized warfare that his name will for ever be inseparably associated. "Fort Pillow Forrest" was the title which the deed conferred upon him, and by this he will be remembered by the present generation, and by it he will pass into history. The massacre occurred on the 12th of April, 1864. Fort Pillow is 65 miles above Memphis, and its capture was effected during Forrest's celebrated raid through Tennessee, a State which was at the time practically in possession of the Union forces. ..."

- "Late in March (Forrest) passed into that State, and the route of his advance was marked by outrages and brutalities of the most cold-blooded character. He captured most of the small garrisons on his line of march, in each case summoning the defenders to surrender under a threat that if he had to storm the works he would give no quarter. On the 12th of April he appeared before Fort Pillow. This fort was garrisoned by 500 troops, about half of them colored. Forrest's force numbered about 5,000 or 6,000. His first attack was a complete surprise, and the commanding officer was killed early in the engagement. Still the defenders fought so gallantly that at 2 o'clock the enemy had gained no material advantage. Forrest then sent in a flag of truce, demanding unconditional surrender. After a short consultation, Major Bradford, on whom the command had devolved, sent word refusing to surrender. Instantly the bugles sounded the assault. The enemy were now within 100 yards of the fort, and at the sound they rushed on the works, shouting. The garrison was seized with a panic: the men threw down their arms and sought safety in flight toward the river, in the neighboring ravine, behind logs, bushes, trees, and in fact everywhere where there was a chance for concealment. It was in vain. The captured fort and its vicinity became a human shambles."

- "Forrest reported his own loss at 20 killed and 60 wounded; and states that he buried 228 Federals on the evening of the assault. Yet in the face of this he claimed that the Fort Pillow capture was "a bloody victory, only made a massacre by dastardly Yankee reporters." The news of the massacre aroused the whole country to a paroxysm of horror and fury."...

These claims were directly disputed in letters, written by Confederate soldiers to their own families, which described wanton brutality on the part of Confederate troops.[41]

The New York newspaper obituary further stated:

- "Since the war, Forrest has lived at Memphis, and his principal occupation seems to have been to try and explain away the Fort Pillow affair. He wrote several letters about it, which were published, and always had something to say about it in any public speech he delivered. He seemed as if he were trying always to rub away the blood stains which marked him."[12]

Continuing controversies

On February 10, 2011 Fox News Channel reported that there is a proposal in Mississippi to issue specialty license plates, honoring Forrest, to mark the 150th anniversary of the "War Between the States".[91] Forrest's legacy still draws heated public debate, as he has been called "one of the most controversial – and popular – icons of the war."[92] The Sons of Confederate Veterans helped sponsor a set of Mississippi license plates commemorating the Civil War, for which the 2014 version featuring Forrest drew controversy in 2011. The Mississippi NAACP petitioned Governor Haley Barbour to denounce the plates and prevent their distribution.[93] Barbour refused to denounce the honor, noting instead that the state legislature would not be likely to approve the plate anyway.[94]

In 2000, a monument to Forrest in Selma, Alabama, was unveiled.[95] On March 10, 2012, it was vandalized and the bronze bust of the general vanished. In August, a historical society called Friends of Forrest moved forward with plans for a new, larger monument, which was to be 12 feet high, illuminated by L.E.D. lights, surrounded by a wrought-iron fence and protected by 24-hour security cameras. The plans triggered outrage and a group of around 20 protesters attempted to block construction of the new monument by lying in the path of a concrete truck. Local lawyer and radio host Rose Sanders said, "Glorifying Nathan B. Forrest here is like glorifying a Nazi in Germany. For Selma, of all places, to have a big monument to a Klansman is totally unacceptable."[96] An online petition at Change.org asking the City Council to ban the monument collected more than 285,000 signatures by mid-September.

In 2015, as a result of the June 17 church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, some Tennessee lawmakers advocated removing a bust of Forrest located in the State's Capitol building. Subsequently, then-Mayor A.C. Wharton urged removal of the statue of Confederate Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest in Health Sciences Park and suggested relocation of Bedford Forrest and his wife to their original burial site in nearby Elmwood Cemetery.[97] In a nearly unanimous vote on July 7, the Memphis City Council passed a resolution in favor of removing the statue and securing the couple's remains for transfer. The Tennessee Historical Commission denied removal on October 21, 2016 under its authority granted by The Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013, which protects war memorials on public property from cities or counties relocating, removing, renaming, or otherwise disturbing them.[98]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- Cavalry in the American Civil War

- Forrest City, Arkansas

- Forrest County, Mississippi

- Emma Sansom

- Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park

Notes

- ^ a b The Language of the Civil War, John D. Wright, Greenwood Publishing Group, (2001), p. 210 & p. 326

- ^ Slowly by Slowly, Patrick S. Beard, Xulon Press, 30 Jul 2009, p. 33

- ^ Morton, John Watson (1909). The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest's Cavalry: "the Wizard of the Saddle,". Publishing house of the M. E. Church, South, Smith & Lamar, agents. p. 1.

- ^ Foote, p. 1053

- ^ "That Devil Forrest;" Foreword by Albert Castel

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hy8bWsCAETc

- ^ Willis. p. 336.

- ^ John Allan Wyath, That Devil Forrest, pp. 2–4

- ^ Gitlin, Marty (2009). The Ku Klux Klan: A Guide to an American Subculture. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 9780313365768.

- ^ "Domestic slave trade site". Inmotionaame.org. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ Winik, Jay (2002). April 1865: The Month That Saved America. Harper Perennial. p. 176. ISBN 9780060930882.

- ^ a b c "Death of General Forrest". On This Day. The New York Times. 30 October 1877.

- ^ https://www.geni.com/people/Lt-Gen-Nathan-Bedford-Forrest-CSA/6000000007167954829

- ^ From an address by General J.R. Charlmers in 1879. "Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest And His Campaigns". Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. VII. Richmond, Virginia, October 1879, No. 10. Southern Historical Society Papers. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nathan Bedford Forrest Biography at Civil War Home". CivilWarHome.com. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ "Tennesseans in the Civil War". Tngenweb.org. August 17, 2004. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ Cheryl Hiers, "New Statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest Raises Old Controversy in Nashville", Blueshoe Nashville Travel Guide, 1998.

- ^ Ken Burns' Civil War, Episode 7: "Most Hallowed Ground"

- ^ John C. Fredriksen (December 5, 2001). America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 163. ISBN 1576076032. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ "The Forrest – Gould Affair, Columbia, Tennessee ~~ June 13, 1863". Tennessee-SCV.org. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ Davison, E. W.; D. Foxx (2007). Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of the Enigma. Pelican Publishing. pp. 36–41. ISBN 1589804155.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Wills, p. 66.

- ^ http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Nathan_Bedford_Forrest

- ^ Wills, p. 70.

- ^ Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative, Volume One, p. 350

- ^ *Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. The Civil War Dictionary, New York: McKay, 1959; revised 1988, p. 289

- ^ "Official Records, Series I, Vol XVI Part I, p. 805, Lieutenant Co Parkhurst's Report (9th Michigan Infantry) on General Forrest's attack at Murfreesboro, Tenn, July 13, 1862". Library.Cornell.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ a b Eicher, p. 240.

- ^ Foote, II, p. 65.

- ^ Robert Willett, The Lightning Mule Brigade: The 1863 Raid of Abel Streight into Alabama, Emmis Books, 1999

- ^ Foote, II, p. 759.

- ^ Foote, II, p. 760.

- ^ Failure in the Saddle: Nathan Bedford Forrest, Joseph Wheeler, and the Confederate Cavalry in the Chickamauga Campaign, Appendix Four, by David A. Powell, ISBN 978-1-932714-87-6

- ^ Presentation to Chicago Civil War Round Table, Dr. Lawrence Lee Hewitt, November 2013

- ^ Eicher, p. 809

- ^ United States. War Dept, Henry Martyn Lazelle, Leslie J. Perry (1891). The War of the Rebellion: v. 1–53 [serial no. 1–111] Formal reports, both . Washington: Government Printing Office. p. 547.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lincoln, Abraham. "Abraham Lincoln to Cabinet, Tuesday, May 03, 1864 (Fort Pillow massacre)," Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. May 3, 1864. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html (accessed July 11, 2015).

- ^ Jordon, General Thomas; Pryor, J. P. (1868). The Campaigns Of General Nathan Bedford Forrest And Of Forrest's Cavalry. pp. 430–435.

- ^ Bailey, p. 25.

- ^ Cimprich and Mainfort, pp. 293–306.

- ^ a b Clark, Achilles V.

- ^ Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume II, Chapter XLVII.

- ^ William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman (Library of America, 1990), 463.

- ^ https://archive.org/details/fortpillowmassac00unit

- ^ William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman (Library of America, 1990), 470.

- ^ Richard Fuchs, An Unerring Fire: The Massacre At Fort Pillow (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2002), 14.

- ^ Andrew Ward, River Run Red: The Fort Pillow Massacre in the American Civil War (New York: Penguin, 2005), 227.

- ^ John Cimprich, Fort Pillow: A Civil War Massacre and Public Memory (Louisiana State University Press, 2005), 123–124.

- ^ Col. Howard Lee Landers, Battle of Brice's Cross Roads, Mississippi. June 10, 1864 Washington, DC: Historical Section, Army War College, 1928.

- ^ Wills, Brian Steel (1993). A Battle from the Start: The life of Nathan Bedford Forrest. Harper Perennial. p. 215. ISBN 9780060924454.

- ^ Foote, p. 1002

- ^ Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T.; Coles, David J., eds. (September 16, 2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 722. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ Catton, p. 160.

- ^ Dillon, Francis H. "for example". George Mason University. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ Times, New York (1918), Forrest, retrieved 2012-10-10

- ^ Catton, pp. 160–61.

- ^ http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a283415.pdf

- ^ Davidson, Eddy W. Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of the Enigma, pg. 474.

- ^ Wills p. 336

- ^ Hurst pp. 284–285. Wills, p. 336. Wills quotes two KKK members who identified Forrest as a Klan leader. James R. Crowe stated, "After the order grew to large numbers we found it necessary to have someone of large experience to command. We chose General Forrest." Another member wrote, "N. B. Forest of Confederate fame was at our head, and was known as the Grand Wizard. I heard him make a speech in one of our Dens."

- ^ Bust Hell Wide Open: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest by Samual W. Mitcham Jr.

- ^ Wills p. 338

- ^ Ward p. 386

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-a-tures/general-nathan-bedford-fo_b_7734444.html

- ^ Eddy W. Davison’s “Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of the Enigma,” p. 464 and 474-475.

- ^ Joint Select Committee On The Condition Of Affairs In The Late Insurrectionary States, United States. Congress; Poland, Luke Potter; Scott, John (1872). Report of the Joint Select Committee Appointed to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary State. p. 12.

- ^ Joint Select Committee On The Condition Of Affairs In The Late Insurrectionary States, United States. Congress; Poland, Luke Potter; Scott, John (1872). Report of the Joint Select Committee Appointed to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary State. p. 463.

- ^ Memphis Appeal, July 5, 1875

- ^ "Ex-Confederates: Meeting of Cavalry Survivor's Association" (PDF). Chronicle. Augusta, Georgia. July 31, 1875. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Andy (August 20, 2013). "Confederate Veterans on Forrest: 'Unworthy of a Southern gentleman'". Dead Confederates: A Civil War Era Blog. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ "Macon Weekly Telegraph". Macon Weekly Telegraph. Georgia. July 20, 1875. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Andy (December 11, 2011). "Nathan Bedford Forrest Joins the Klan". Dead Confederates: A Civil War Era Blog. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ a b Foote, III, p. 1052

- ^ Paul Ashdown; Edward Caudill (1 January 2006). The Myth of Nathan Bedford Forrest. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-7425-4301-0.

- ^ The park was renamed Health Sciences Park on February 5, 2013. Sainz, Adrian. "Memphis renames 3 parks that honored Confederacy". Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Council Votes To Move Nathan Bedford Forrest's Remains". LocalMemphis. Retrieved 2015-07-13.

- ^ Sainz, Adrian. "Memphis renames 3 parks that honored Confederacy". Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Loewen, James W. (2007). Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. Simon and Schuster. p. 237.

- ^ "Tennessee Code Annotated 15-2-101". LexisNexis. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ Dale Cox (2012-08-23). "Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument – Selma, Alabama". Exploresouthernhistory.com. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ a b "Florida School Board Votes To Remove Name Of Civil War General Tied To Ku Klux". Business Insider. Nov 9, 2013. Retrieved Nov 10, 2013.

- ^ "Florida High School Keeps KKK Founder's Name". Fox News. November 10, 2008.

- ^ "Confederate general's name removed from Army's road". Deseret News. 1 August 2000.

- ^ Long, Trish (June 5, 2010). "Soldier turned down film job to fight, die in Korea". El Paso Times.

Forrest Road was renamed Cassidy Road in honor of Lt. Gen. Richard T. Cassidy, who commanded Fort Bliss from 1968 to 1971

- ^ "Gate Schedule". El Paso Herald-Post. El Paso, Texas. February 22, 1975. p. 8.

the gate station established on Forrest road is another step in the implementation of a phased traffic control and security program announced last month at Fort Bliss. The Forrest road site was selected for the first of the several gate stations

- ^ Scott Barker, "Nathan Forrest: Still confounding, controversial," Knoxville News Sentinel, February 19, 2006.

- ^ Yeagar, Charles Gordon (1987). Fightin' With Forrest. Dixie Pub. Co. ISBN 0-9619244-0-3.

- ^ Carter, William C. (1989), Conversations with Shelby Foote, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 0-87805-385-9

- ^ "Official Records, Series I, Vol. 32, Part 1, pp. 569–570: Report of Lieutenant Daniel Van Horn, Sixth U. S. Colored Heavy Artillery, of the capture of Fort Pillow". Ebooks.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ Stewart, Charles W. (1914). Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I Volume 26. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 234.

I hereby acknowledge to have received from Major-General Forrest 2 first and 1 second lieutenants, 43 white privates, and 14 negroes.

- ^ "Proposed Mississippi License Plate Would Honor Early KKK Leader". Fox News. February 10, 2011.

- ^ "KKK leader on specialty license plates? Plan in Mississippi raises hackles". Christian Science Monitor. February 11, 2011.

- ^ "Group Wants KKK Founder Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest on License Plate". ABC News. February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Haley Barbour Won't Denounce Proposal Honoring Confederate General, Early KKK Leader". CBS News. February 16, 2011.

- ^ http://www.exploresouthernhistory.com/selmaforrest.html

- ^ "Bust of Civil War General Stirs Anger in Alabama". New York Times. August 24, 2012.

- ^ "Mayor Wharton: Remove Nathan Bedford Forrest statue and body from park".

- ^ http://www.knoxnews.com/story/news/local/tennessee/2016/10/21/nathan-bedford-forrest-wont-be-moved/92510072/

References

- Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books, Battles for Atlanta: Sherman Moves East, Time Life Books, 1985, ISBN 0-8094-4773-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. (1988) [1959]. The Civil War Dictionary. New York, New York: McKay. ISBN 0-8129-1726-X.

- Catton, Bruce. (1971). The Civil War. American Heritage Press, New York. Library of Congress Number: 77-119671.

- Cimprich, John, and Mainfort, Robert C., Jr., eds. "Fort Pillow Revisited: New Evidence About An Old Controversy", Civil War History 4 (Winter, 1982).

- Clark, Achilles V., "A Letter of Account", ed. by Dan E. Pomeroy, Civil War Times Illustrated, 24(4): 24–25, June 1985.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Johnson, Curt, and Bongard, David L., Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, Castle Books, 1992, 1st Ed., ISBN 0-7858-0437-4.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution 1863–1877. (1988) ISBN 0-06-015851-4.

- Foote, Shelby, The Civil War: A Narrative – II: Fredericksburg to Meridian, Random House, 1963, ISBN 0-394-74621-X

- Foote, Shelby, The Civil War: A Narrative – III: Red River to Appomattox, Random House, 1974, ISBN 0-394-74622-8

- Hurst, Jack. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography, 1993.

- Lytle, Andrew Nelson (1992) [1931]. Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company. Nashville, Tennessee: J.S. Sanders and Company. ISBN 1-879941-09-0.

- Sherman, William T., "Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman." Library of America, 1990. ISBN 9780940450653.

- Ward, Andrew. River Run Red: The Fort Pillow Massacre in the American Civil War. Viking Penguin: 2005.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Wills, Brian Steel (1992). A Battle from the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest. New York, New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-092445-4.

Further reading

- Bearss, Edwin C. Forrest at Brice's Cross Roads and in North Mississippi in 1864. Dayton OH: Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1979.

- Bearss, Ed. Unpublished remarks to Gettysburg College Civil War Institute, July 1, 2005.

- Bradshaw, Wayne. The Civil War Diary of William R. Dyer: A Member of Forrest's Escort, BookSurge Publishing, 2009, ISBN 1-4392-3772-7.

- Carney, Court, "The Contested Image of Nathan Bedford Forrest", Journal of Southern History. Volume: 67. Issue: 3., 2001, pp. 601+.

- Davison, Eddy W. and Daniel Foxx. Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of the Enigma. Pelican Publishing Company, 2007. p. 528.

- Harcourt, Edward John. "Who Were the Pale Faces? New Perspectives on the Tennessee Ku Klux", Civil War History. Volume: 51. Issue: 1, 2005, pp: 23+.

- Henry, Robert Selph. First with the Most, 1944.

- Horn, Stanley F., Invisible Empire: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan, 1866–1871, Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith Publishing Corporation, 1939.

- Hurst, Jack. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. (1993)

- Kastler, Shane. Nathan Bedford Forrest's Redemption (2010), Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58980-834-8.

- Lytle, Andrew Nelson. Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company, 1931, Reprint by Ivan R. Dee, 2002, ISBN 978-1-879941-09-0.

- Tap, Bruce. "'These Devils are Not Fit to Live on God's Earth': War Crimes and the Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1864–1865," Civil War History, XLII (June 1996), 116–32. on Ft Pillow.

- Williams, Edward F. Fustest with the mostest; the military career of Tennessee's greatest Confederate, Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest Memphis, Distributed by Southern Books, 1969.

- Wills, Brian Steel. A Battle from the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest, 1992, ISBN 0-06-016832-3.

- Wyeth, John Allan. That Devil Forrest, 1899 (original) republished in 1989 by Louisiana State University Press.

External links

- Forrest Biography (early years and wartime service) at civilwarhome.com

- Animated History of The Campaigns of Nathan Bedford Forrest at civilwaranimated.com

- General Nathan Bedford Forrest Historical Society

- Interview with Nathan Bedford Forrest ca. 1868 in Wikisource

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

- Nathan Bedford Forrest

- 1821 births

- 1877 deaths

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- Tennessee Democrats

- People from Marshall County, Tennessee

- People of Tennessee in the American Civil War

- Confederate States Army lieutenant generals

- Deaths from diabetes

- Ku Klux Klan members

- American slave traders

- American slave owners

- Cavalry commanders