National debt of the United States: Difference between revisions

Updated Graph |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2011}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2011}} |

||

{{U.S. Deficit and Debt Topics}} |

{{U.S. Deficit and Debt Topics}} |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Ronwai01.JPG|thumb|420px|U.S. federal debt held by the public as a percentage of GDP, from 1940 to 2012]] |

||

The '''national debt of the United States''' is the amount owed by the [[federal government of the United States]]. The measure of the [[government debt|public debt]] is the value of the [[United States Treasury security|Treasury securities]] that have been issued by the [[United States Treasury|Treasury]] and other federal government agencies{{which|date=October 2013}} and which are outstanding at that point of time. |

The '''national debt of the United States''' is the amount owed by the [[federal government of the United States]]. The measure of the [[government debt|public debt]] is the value of the [[United States Treasury security|Treasury securities]] that have been issued by the [[United States Treasury|Treasury]] and other federal government agencies{{which|date=October 2013}} and which are outstanding at that point of time. |

||

Gross public debt consists of two components:<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.gao.gov/special.pubs/longterm/debt/debtbasics.html#largefeddebt |title=Federal debt basics – How large is the federal debt? |publisher=[[Government Accountability Office]] |accessdate=April 28, 2012}}</ref> |

Gross public debt consists of two components:<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.gao.gov/special.pubs/longterm/debt/debtbasics.html#largefeddebt |title=Federal debt basics – How large is the federal debt? |publisher=[[Government Accountability Office]] |accessdate=April 28, 2012}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:44, 8 July 2014

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Budget and debt in the United States of America |

|---|

|

The national debt of the United States is the amount owed by the federal government of the United States. The measure of the public debt is the value of the Treasury securities that have been issued by the Treasury and other federal government agencies[which?] and which are outstanding at that point of time. Gross public debt consists of two components:[1]

- Debt held by the public, such as Treasury securities held by investors outside the federal government, including those held by individuals, corporations, the Federal Reserve System and foreign, state and local governments.

- Debt held by government accounts or intragovernmental debt, such as non-marketable Treasury securities held in accounts administered by the federal government that are owed to program beneficiaries, such as the Social Security Trust Fund. Debt held by government accounts represents the cumulative surpluses, including interest earnings, of these accounts that have been invested in Treasury securities.

In general, debt held by the public increases as a result of government spending and decreases as a result of government tax or other receipts, which fluctuate in the course of the fiscal year, and in practice Treasury securities are not issued or redeemed on a day-by-day basis.[2] (Treasury securities may also be issued or redeemed as part of government macroeconomic management.) The aggregate, gross amount that Treasury can borrow is limited by the United States debt ceiling.[3]

Historically, the US public debt as a share of GDP increased during wars and recessions, and subsequently declined. For example, debt held by the public as a share of GDP peaked just after World War II (113% of GDP in 1945), but then fell over the following 30 years. In recent decades, however, large budget deficits and the resulting increases in debt have led to concern about the long-term sustainability of the federal government's fiscal policies.[4] The ratio of debt to GDP may decrease as a result of a government surplus as well as due to growth of GDP and inflation.

On June 30, 2014, debt held by the public was approximately $12.6 trillion or about 74% of Q1 2014 GDP[5][6] Intragovernmental holdings stood at $5.1 trillion (30%), giving a combined total public debt of $17.6 trillion or about 104% of Q1 2014 GDP.[7] As of January 2013, $5 trillion or approximately 47% of the debt held by the public was owned by foreign investors, the largest of which were the People's Republic of China and Japan at just over $1.1 trillion each.[8]

History

Except for about a year during 1835–1836, the United States has continuously held a public debt since the US Constitution legally went into effect on March 4, 1789. Public debt as a percentage of GDP reached its highest level during Harry Truman's first presidential term, during and after World War II, but fell rapidly in the post-World War II period, and reached a low in 1973 under President Richard Nixon. Debt as a percentage of GDP has consistently increased since then, except during the presidencies of Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton.

Valuation and measurement

Public and government accounts

On June 28, 2013, debt held by the public was approximately $11.901 trillion or about 71.43% of GDP.[6][7] Intragovernmental holdings stood at $4.837 trillion, giving a combined total public debt of $16.738 trillion.[7]

The national debt can also be classified into marketable or non-marketable securities. As of March 2012, total marketable securities were $10.34 trillion while the non-marketable securities were $5.24 trillion.[9] Most of the marketable securities are Treasury notes, bills, and bonds held by investors and governments globally. The non-marketable securities are mainly the "government account series" owed to certain government trust funds such as the Social Security Trust Fund, which represented $2.7 trillion in 2011.[10] The non-marketable securities represent amounts owed to program beneficiaries. For example, in the case of the Social Security Trust Fund, the payroll taxes dedicated to Social Security were credited to the Trust Fund upon receipt, but spent for other purposes. If the government continues to run deficits in other parts of the budget, the government will have to issue debt held by the public to fund the Social Security Trust Fund, in effect exchanging one type of debt for the other.[11] Other large intragovernmental holders include the Federal Housing Administration, the Federal Savings and Loan Corporation's Resolution Fund and the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund (Medicare).

Accounting treatment

Only debt held by the public is reported as a liability on the consolidated financial statements of the United States government. Debt held by government accounts is an asset to those accounts but a liability to the Treasury; they offset each other in the consolidated financial statements.[12]

Government receipts and expenditures are normally presented on a cash rather than an accruals basis, although the accrual basis may provide more information on the longer-term implications of the government's annual operations.[13]

The United States public debt is often expressed as a ratio of public debt to gross domestic product (GDP). The ratio of debt to GDP may decrease as a result of a government surplus as well as due to growth of GDP and inflation.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac obligations excluded

Under normal accounting rules, fully owned companies would be consolidated into the books of the owner, but the large size of Fannie and Freddie has made the U.S. government reluctant to incorporate Freddie and Fannie into its own books. When Freddie and Fannie required bail-outs, White House Budget Director Jim Nussle, on September 12, 2008, initially indicated their budget plans would not incorporate the GSE debt into the budget because of the temporary nature of the conservator intervention.[14] As the intervention has dragged out, pundits have started to further question this accounting treatment, noting that changes in August 2012 "makes them even more permanent wards of the state and turns the government's preferred stock into a permanent, perpetual kind of security".[15] The government controls the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which would normally criticize inconsistent accounting practices, but it does not oversee its own government's accounting practices or the standards set by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board. The on- or off-balance sheet obligations of those two independent GSEs was just over $5 trillion at the time the conservatorship was put in place, consisting mainly of mortgage payment guarantees and agency bonds.[16] The confusing independent but government-controlled status of the GSEs has resulted in investors of the legacy common shares and preferred shares launching various activist campaigns in 2014.[17]

Guaranteed obligations excluded

U.S. federal government guarantees are not included in the public debt total, until such time as there is a call on the guarantees. For example, the U.S. federal government in late-2008 guaranteed large amounts of obligations of mutual funds, banks, and corporations under several programs designed to deal with the problems arising from the late-2000s financial crisis. The funding of direct investments made in response to the crisis, such as those made under the Troubled Assets Relief Program, are included in the debt.

Unfunded obligations excluded

The U.S. government is obligated under current law to make mandatory payments for programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) projects that payouts for these programs will significantly exceed tax revenues over the next 75 years. The Medicare Part A (hospital insurance) payouts already exceed program tax revenues, and social security payouts exceeded payroll taxes in fiscal 2010. These deficits require funding from other tax sources or borrowing.[18] The present value of these deficits or unfunded obligations is an estimated $45.8 trillion. This is the amount that would have had to be set aside in 2009 in order to pay for the unfunded obligations which, under current law, will have to be raised by the government in the future. Approximately $7.7 trillion relates to Social Security, while $38.2 trillion relates to Medicare and Medicaid. In other words, health care programs will require nearly five times more funding than Social Security. Adding this to the national debt and other federal obligations would bring total obligations to nearly $62 trillion.[19] However, these unfunded obligations are not counted in the national debt.

Measuring debt burden

GDP is a measure of the total size and output of the economy. One measure of the debt burden is its size relative to GDP, called the "Debt to GDP ratio." Mathematically, this is the debt divided by the GDP amount. The Congressional Budget Office includes historical budget and debt tables along with its annual "Budget and Economic Outlook." Debt held by the public as a percentage of GDP rose from 34.7% GDP in 2000 to 40.5% in 2008 and 67.7% in 2011.[20]

Mathematically, the ratio can decrease even while debt grows, if the rate of increase in GDP (which also takes account of inflation) is higher than the rate of increase of debt. Conversely, the debt to GDP ratio can increase even while debt is being reduced, if the decline in GDP is sufficient.

According to the CIA World Factbook, during 2011, the U.S. debt to GDP ratio of 67.8% was the 38th highest in the world. This was measured using "debt held by the public."[21] However, this number excludes state and local debt. According to the OECD, general government gross debt (federal, state, and local) in the United States in the third quarter of 2012 was $16.3 trillion, 108% of GDP.[22]

The ratio is higher if the total national debt is used, by adding the "intragovernmental debt" to the "debt held by the public." For example, on January 10, 2013, debt held by the public was approximately $11.577 trillion or about 73% of GDP. Intra-governmental holdings stood at $4.855 trillion, giving a combined total public debt of $16.432 trillion. U.S. GDP in 2012 was approximately $15.6 trillion, for a total debt to GDP ratio of approximately 105%.[9][23][23][24]

Calculating the annual change in debt

The annual change in debt is not equal to the "total deficit." Social Security payroll taxes and benefit payments, along with the net balance of the U.S. Postal Service, are considered "off-budget", while most other expenditure and receipt categories are considered "on-budget." The total federal deficit is the sum of the on-budget deficit (or surplus) and the off-budget deficit (or surplus). Since FY1960, the federal government has run on-budget deficits except for FY1999 and FY2000, and total federal deficits except in FY1969 and FY1998–FY2001.[25]

In large part because of Social Security surpluses, the total deficit is smaller than the on-budget deficit. The surplus of Social Security payroll taxes over benefit payments is spent by the government for other purposes. However, the government credits the Social Security Trust fund for the surplus amount, adding to the "intragovernmental debt." The total federal debt is divided into "intragovernmental debt" and "debt held by the public." In other words, spending the "off budget" Social Security surplus adds to the total national debt (by increasing the intragovernmental debt) while the surplus reduces the "total" deficit reported in the media.

Certain spending called "supplemental appropriations" is outside the budget process entirely but adds to the national debt. Funding for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars was accounted for this way prior to the Obama administration. Certain stimulus measures and earmarks are also outside the budget process.

For example, in FY2008 an off-budget surplus of $183 billion reduced the on-budget deficit of $642 billion, resulting in a total federal deficit of $459 billion. Media often reported the latter figure. The national debt increased by $1,017 billion between the end of FY2007 and the end of FY2008.[26] The federal government publishes the total debt owed (public and intragovernmental holdings) at the end of each fiscal year[27] and since FY1957 the amount of debt held by the federal government has increased each year.

Reduction

Contrary to popular belief, reducing the debt burden (i.e., lowering the ratio of debt relative to GDP) is almost always accomplished without running budget surpluses. The U.S. has only run surpluses in four of the past 40 years (1998-2001) but had several periods where the debt to GDP ratio was lowered. This was accomplished by growing GDP (in real terms and via inflation) relatively faster than the increase in debt.

Negative real interest rates

Since 2010, the U.S. Treasury has been obtaining negative real interest rates on government debt, meaning the inflation rate is greater than the interest rate paid on the debt.[28] Such low rates, outpaced by the inflation rate, occur when the market believes that there are no alternatives with sufficiently low risk, or when popular institutional investments such as insurance companies, pensions, or bond, money market, and balanced mutual funds are required or choose to invest sufficiently large sums in Treasury securities to hedge against risk.[29][30] Economists such as Lawrence Summers and bloggers such as Matthew Yglesias have stated that at such low interest rates, government borrowing actually saves taxpayer money and improves creditworthiness.[31][32]

In the late 1940s through the early 1970s, the US and UK both reduced their debt burden by about 30% to 40% of GDP per decade by taking advantage of negative real interest rates, but there is no guarantee that government debt rates will continue to stay so low.[29][33] Between 1946 and 1974, the US debt-to-GDP ratio fell from 121% to 32% even though there were surpluses in only eight of those years which were much smaller than the deficits.[34]

Converting fractional reserve to full reserve banking

The two economists, Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof, working for the International Monetary Fund published a working paper called The Chicago Plan Revisited suggesting that the debt could be eliminated by raising bank reserve requirements, converting from fractional reserve banking to full reserve banking.[35][36] Economists at the Paris School of Economics have commented on the plan, stating that it is already the status quo for coinage currency,[37] and a Norges Bank economist has examined the proposal in the context of considering the finance industry as part of the real economy.[38] A Centre for Economic Policy Research paper agrees with the conclusion that, "no real liability is created by new fiat money creation, and therefore public debt does not rise as a result."[39]

Debt ceiling

Relationship to appropriation process

The present debt ceiling is an aggregate limit applied to nearly all federal debt, which was substantially established by the Public Debt Acts[40][41] of 1939 and 1941 and subsequently amended to change the ceiling amount.

The process of setting the debt ceiling is separate and distinct from the federal budget process, and raising the debt ceiling does not have any direct impact on the budget deficit. The U.S. President proposes a federal budget every year. This budget details projected tax collections and outlays and, if there is a budget deficit, the amount of borrowing the President is proposing in that fiscal year. Congress creates specific appropriation bills which authorize spending, which are signed into law by the President.

A vote to increase the debt ceiling is, therefore, usually treated as a formality, needed to continue spending that has already been approved previously by the Congress and the President. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) explains: "The debt limit does not control or limit the ability of the federal government to run deficits or incur obligations. Rather, it is a limit on the ability to pay obligations already incurred."[42] The apparent redundancy of the debt ceiling has led to suggestions that it should be abolished altogether.[43][44]

Since 1979, the House of Representatives passed a rule to automatically raise the debt ceiling when passing a budget, without the need for a separate vote on the debt ceiling, except when the House votes to waive or repeal this rule. The exception to the rule was invoked in 1995, which resulted in two government shutdowns.[45]

Treasury measures when debt ceiling is reached

The Treasury is authorized to issue debt needed to fund government operations (as authorized by each federal budget) up to a stated debt ceiling, with some small exceptions. When the debt ceiling is reached, Treasury can declare a debt issuance suspension period and utilize "extraordinary measures" to acquire funds to meet federal obligations but which do not require the issue of new debt. One example is to suspend contributions to certain government pension funds. However, these amounts are not sufficient to cover government operations.[46] Treasury first used these measures on December 16, 2009, to remain within the debt ceiling, and avoid a government shutdown,[47] and also used it during the debt-ceiling crisis of 2011. However, there are limits to how much can be raised by these measures.[48]

History

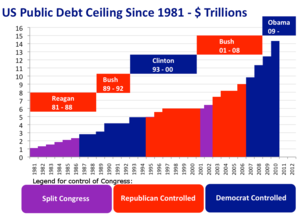

Between 1940 and January 2013, the debt ceiling was raised 54 times during Republican presidential administrations and 40 times during Democratic administrations. The ceiling was raised the most times (18) during President Reagan's administration, with no other President exceeding 10 times. During President Obama's first term, the ceiling was raised six times.[50]

The debt ceiling was increased on February 12, 2010, to $14.294 trillion.[51][52][53] On April 15, 2011, Congress finally passed the 2011 United States federal budget, authorizing federal government spending for the remainder of the 2011 fiscal year, which ends on September 30, 2011, with a deficit of $1.48 trillion, [citation needed] without voting to increase the debt ceiling. The two Houses of Congress were unable to agree on a revision of the debt ceiling in mid-2011, resulting in the United States debt-ceiling crisis. The impasse was resolved with the passing on August 2, 2011, the deadline for a default by the U.S. government on its debt, of the Budget Control Act of 2011, which immediately increased the debt ceiling to $14.694 trillion, required a vote on a Balanced Budget Amendment, and established several complex mechanisms to further increase the debt ceiling and reduce federal spending.

On September 8, 2011, one of the complex mechanisms to further increase the debt ceiling took place as the Senate defeated a resolution to block a $500 billion automatic increase. The Senate's action allowed the debt ceiling to increase to $15.194 trillion, as agreed upon in the Budget Control Act.[54] This was the third increase in the debt ceiling in 19 months, the fifth increase since President Obama took office, and the twelfth increase in 10 years. The August 2 Act also created the United States Congress Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction for the purpose of developing a set of proposals by November 23, 2011, to reduce federal spending by $1.2 trillion. The Act required both houses of Congress to convene an "up-or-down" vote on the proposals as a whole by December 23, 2011. The Joint Select Committee met for the first time on September 8, 2011. The debt ceiling was raised once more on January 30, 2012, to a new high of $16.394 trillion.

At midnight on December 31, 2012, a major provision of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) was scheduled to go into effect. The crucial part of the Act provided for a Joint Select Committee of Congressional Democrats and Republicans—the so-called "Supercommittee"—to produce bipartisan legislation by late November 2012 that would decrease the U.S. deficit by $1.2 trillion over the next 10 years. To do so, the committee agreed to implement by law—if no other deal was reached before Dec. 31—massive government spending cuts as well as tax increases or a return to tax levels from previous years. These are the elements that make up the 'United States fiscal cliff.'[55]

The Continuing Appropriations Act suspended the statutory debt limit through February 7, 2014.[48] However, after February 7, the US "would be forced to use extraordinary measures to continue to finance the government on a temporary basis" and "Treasury is more likely to exhaust those measures in late February".[48]

Debt holdings

Because a large variety of people own the notes, bills, and bonds in the "public" portion of the debt, Treasury also publishes information that groups the types of holders by general categories to portray who owns United States debt. In this data set, some of the public portion is moved and combined with the total government portion, because this amount is owned by the Federal Reserve as part of United States monetary policy. (See Federal Reserve System.)

As is apparent from the chart, a little less than half of the total national debt is owed to the "Federal Reserve and intragovernmental holdings". The foreign and international holders of the debt are also put together from the notes, bills, and bonds sections. To the right is a chart for the data as of June 2008:

Foreign holdings

As of January 2011, foreigners owned $4.45 trillion of U.S. debt, or approximately 47% of the debt held by the public of $9.49 trillion and 32% of the total debt of $14.1 trillion.[56] The largest holders were the central banks of China, Japan, Brazil, Taiwan, United Kingdom, Switzerland and Russia.[58] The share held by foreign governments has grown over time, rising from 13% of the public debt in 1988[59] to 25% in 2007.[60]

As of May 2011 the largest single holder of U.S. government debt was China, with 26 percent of all foreign-held U.S. Treasury securities (8% of total U.S. public debt).[61] China's holdings of government debt, as a percentage of all foreign-held government debt, have decreased a bit between 2010 and 2011, but are up significantly since 2000 (when China held just 6 percent of all foreign-held U.S. Treasury securities).[62]

This exposure to potential financial or political risk should foreign banks stop buying Treasury securities or start selling them heavily was addressed in a June 2008 report issued by the Bank of International Settlements, which stated, "Foreign investors in U.S. dollar assets have seen big losses measured in dollars, and still bigger ones measured in their own currency. While unlikely, indeed highly improbable for public sector investors, a sudden rush for the exits cannot be ruled out completely."[63]

On May 20, 2007, Kuwait discontinued pegging its currency exclusively to the dollar, preferring to use the dollar in a basket of currencies.[64] Syria made a similar announcement on June 4, 2007.[65] In September 2009 China, India and Russia said they were interested in buying International Monetary Fund gold to diversify their dollar-denominated securities.[66] However, in July 2010 China's State Administration of Foreign Exchange "ruled out the option of dumping its vast holdings of US Treasury securities" and said gold "cannot become a main channel for investing our foreign exchange reserves" because the market for gold is too small and prices are too volatile.[67]

According to Paul Krugman, "It’s true that foreigners now hold large claims on the United States, including a fair amount of government debt. But every dollar’s worth of foreign claims on America is matched by 89 cents’ worth of U.S. claims on foreigners. And because foreigners tend to put their U.S. investments into safe, low-yield assets, America actually earns more from its assets abroad than it pays to foreign investors. If your image is of a nation that’s already deep in hock to the Chinese, you’ve been misinformed. Nor are we heading rapidly in that direction."[68]

Forecasting

Short-term forecasts

The Congressional Budget Office releases its "Budget and Economic Outlook" annually in January or February, with an update in August. This report covers a ten-year window. CBO projected in August 2012 that the fiscal year 2012 debt held by the public would be $11,318 billion, or 72.8% GDP. CBO projected that if 2012 tax and spending policies were extended (i.e., the "alternate fiscal scenario"), these amounts would rise to $12,460 billion (78.1% GDP) in 2013 and $22,181 billion (89.7% GDP) in 2022. If the U.S. were to experience significant tax increases and spending cuts (i.e., the "baseline scenario") related to the United States fiscal cliff, these amounts would be considerably less in 2013 ($12,064 billion or 76.1% GDP) and 2022 ($14,464 billion or 58.5% GDP).[69]

Long-term trends

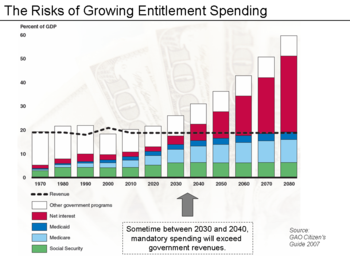

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) wrote in 2008 that: "Future growth in spending per beneficiary for Medicare and Medicaid – the federal government’s major health care programs – will be the most important determinant of long-term trends in federal spending. Changing those programs in ways that reduce the growth of costs – which will be difficult, in part because of the complexity of health policy choices – is ultimately the nation’s central long-term challenge in setting federal fiscal policy."[70]

Demographic shifts and per-capita spending are causing Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid expenditures to grow significantly faster than GDP. If this trend continues, government simulations under various assumptions project mandatory spending for these programs will exceed taxes dedicated to these programs by more than $40 trillion over the next 75 years on a present value basis.[71]

According to the GAO, this will double debt-to-GDP ratios by 2040 and double them again by 2060, reaching 600% by 2080.[72] A GAO simulation indicates that Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid expenditures alone will exceed 20% of GDP by 2080, which is approximately the historical ratio of taxes collected by the federal government. In other words, these mandatory programs alone will take up all government revenues under this simulation.[71]

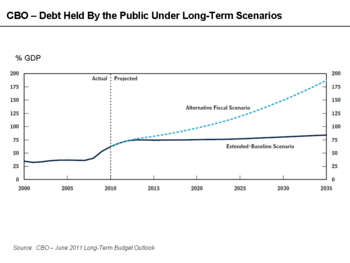

CBO long-term scenarios

The Congressional Budget Office projects the debt as part of its "Long-term Budget Outlook" which is released annually. The 2012 Outlook included projections for debt through 2037. CBO outlined two scenarios, the "Extended Baseline" scenario and "Extended Alternative Fiscal" scenario. The Baseline scenario assumes significant fiscal austerity, with lower debt and deficits via higher tax revenues and lower spending. The Alternative scenario assumes higher debt and deficits via lower tax revenues and higher spending. CBO projected that debt held by the public would be 53% of GDP in 2037 under the Baseline Scenario but 199% under the Alternate Scenario, versus 73% in 2012. CBO has warned that the debt levels under the Alternative scenario would pose significant risks, including much higher interest expenses crowding out government benefits.[73]

CBO estimated in August 2011 that if laws currently "on the books" were enforced without changes, meaning the "extended baseline scenario" described above is implemented along with deficit reductions from the Budget Control Act of 2011, the deficit would decline from 8.5% GDP in 2011 to around 1% GDP by 2021.[74]

The CBO reported in August 2011: "Many budget analysts believe that the alternative fiscal scenario presents a more realistic picture of the nation’s underlying fiscal policies than the extended-baseline scenario does. The explosive path of federal debt under the alternative fiscal scenario underscores the need for large and rapid policy changes to put the nation on a sustainable fiscal course."[74]

Risks and debates

CBO risk factors

The CBO reported several types of risk factors related to rising debt levels in a July 2010 publication:

- A growing portion of savings would go towards purchases of government debt, rather than investments in productive capital goods such as factories and computers, leading to lower output and incomes than would otherwise occur;

- If higher marginal tax rates were used to pay rising interest costs, savings would be reduced and work would be discouraged;

- Rising interest costs would force reductions in government programs;

- Restrictions to the ability of policymakers to use fiscal policy to respond to economic challenges; and

- An increased risk of a sudden fiscal crisis, in which investors demand higher interest rates.[75]

Sustainability

According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the United States is on a fiscally unsustainable path because of projected future increases in Medicare and Social Security spending, and that politicians and the electorate have been unwilling to change this path.[18] Further, the subprime mortgage crisis has significantly increased the financial burden on the U.S. government, with over $10 trillion in commitments or guarantees and $2.6 trillion in investments or expenditures as of May 2009, only some of which are included in the public debt computation.[76] However, these concerns are not universally shared.[77]

Risks to economic growth

Debt levels may affect economic growth rates. In 2010, economists Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart reported that among the 20 developed countries studied, average annual GDP growth was 3–4% when debt was relatively moderate or low (i.e. under 60% of GDP), but it dips to just 1.6% when debt was high (i.e., above 90% of GDP).[78] In April 2013, the conclusions of Rogoff and Reinhart's study have come into question when a coding error in their original paper was discovered by Herndon, Ash and Pollin of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.[79][80] They found that after correcting for errors and unorthodox methods used, there was no evidence that debt above a specific threshold reduces growth.[81] Reinhart and Rogoff maintain that after correcting for errors, a negative relationship between high debt and growth remains.[82] However, other economists, including Paul Krugman, have argued that it is low growth which causes national debt to increase, rather than the other way around.[83][84][85]

A February 2013 paper from four economists concluded that, "Countries with debt above 80 percent of GDP and persistent current-account [trade] deficits are vulnerable to a rapid fiscal deterioration..."[86][87] The statistical relationship between a higher trade deficit and higher interest rates was stronger for several troubled Eurozone countries, indicating significant private borrowing from foreign countries (required to fund a trade deficit) may be a bigger factor than government debt in predicting interest rates.[88]

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke stated in April 2010 that "Neither experience nor economic theory clearly indicates the threshold at which government debt begins to endanger prosperity and economic stability. But given the significant costs and risks associated with a rapidly rising federal debt, our nation should soon put in place a credible plan for reducing deficits to sustainable levels over time."[89]

Mandatory programs

While there is significant debate about solutions,[90] the significant long-term risk posed by the increase in mandatory program spending is widely recognized,[91] with health care costs (Medicare and Medicaid) the primary risk category.[92][93] In a June 2010 opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan noted that "Only politically toxic cuts or rationing of medical care, a marked rise in the eligible age for health and retirement benefits, or significant inflation, can close the deficit."[94] If significant reforms are not undertaken, benefits under entitlement programs will exceed government income by over $40 trillion over the next 75 years.[93]

Interest costs

Despite rising debt levels, interest costs have remained at approximately 2008 levels (around $450 billion in total) due to lower interest rates paid to Treasury debt holders.[95] However, should interest rates return to historical averages, the interest cost would increase dramatically. Historian Niall Ferguson described the risk that foreign investors would demand higher interest rates as the U.S. debt levels increase over time in a November 2009 interview.[96]

Definition of public debt

Economists also debate the definition of public debt. Krugman argued in May 2010 that the debt held by the public is the right measure to use, while Reinhart has testified to the President's Fiscal Reform Commission that gross debt is the appropriate measure.[83] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) cited research by several economists supporting the use of the lower debt held by the public figure as a more accurate measure of the debt burden, disagreeing with these Commission members.[97]

There is debate regarding the economic nature of the intragovernmental debt, which was approximately $4.6 trillion in February 2011.[98] For example, the CBPP argues: that "large increases in [debt held by the public] can also push up interest rates and increase the amount of future interest payments the federal government must make to lenders outside of the United States, which reduces Americans’ income. By contrast, intragovernmental debt (the other component of the gross debt) has no such effects because it is simply money the federal government owes (and pays interest on) to itself."[97] However, if the U.S. government continues to run "on budget" deficits as projected by the CBO and OMB for the foreseeable future, it will have to issue marketable Treasury bills and bonds (i.e., debt held by the public) to pay for the projected shortfall in the Social Security program. This will result in "debt held by the public" replacing "intragovernmental debt".[99][100]

Intergenerational equity

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (March 2013) |

One debate about the national debt relates to intergenerational equity. For example, if one generation is receiving the benefit of government programs or employment enabled by deficit spending and debt accumulation, to what extent does the resulting higher debt impose risks and costs on future generations? There are several factors to consider:

- For every dollar of debt held by the public, there is a government obligation (generally marketable Treasury securities) counted as an asset by investors. Future generations benefit to the extent these assets are passed on to them.[101]

- As of 2010, approximately 72% of the financial assets were held by the wealthiest 5% of the population.[102] This presents a wealth and income distribution question, as only a fraction of the people in future generations will receive principal or interest from investments related to the debt incurred today.

- To the extent the U.S. debt is owed to foreign investors (approximately half the "debt held by the public" during 2012), principal and interest are not directly received by U.S. heirs.[101]

- Higher debt levels imply higher interest payments, which create costs for future taxpayers (e.g., higher taxes, lower government benefits, higher inflation, or increased risk of fiscal crisis).[75]

- To the extent the borrowed funds are invested today to improve the long-term productivity of the economy and its workers, such as via useful infrastructure projects or education, future generations may benefit.[103]

- For every dollar of intragovernmental debt, there is an obligation to specific program recipients, generally non-marketable securities such as those held in the Social Security Trust Fund. Adjustments that reduce future deficits in these programs may also apply costs to future generations, via higher taxes or lower program spending.

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in March 2013 that by neglecting public investment and failing to create jobs, we are doing far more harm to future generations than merely passing along debt: "Fiscal policy is, indeed, a moral issue, and we should be ashamed of what we’re doing to the next generation’s economic prospects. But our sin involves investing too little, not borrowing too much." Young workers face high unemployment and studies have shown their income may lag throughout their careers as a result. Teacher jobs have been cut, which could affect the quality of education and competitiveness of younger Americans.[104]

Appendix

National debt for selected years

| End of Fiscal Year |

Gross debt in $billions undeflated Treas.[105] |

Gross debt in $billions undeflated OMB[106][107] |

as % of GDP Low-High est. or BEA/OMB (a – Treas. audit) |

Debt held by public ($billions) |

as % of GDP (Treas/MW, OMB or Treas/BEA) |

GDP $billions BEA/OMB[108] est.=MW.com |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 2.65 | 8.0 | 2.65 | 8.0 | est. 32.8 | |

| 1920 | 25.95 | 29.2 | 25.95 | 29.2 | est. 88.6 | |

| 1927 | [109] 18.51 | 19.2 | 18.51 | 19.2 | est. 96.5 | |

| 1930 | 16.19 | 16.6 | 16.19 | 16.6 | est. 97.4 | |

| 1940 | 42.97 | 50.70 | 44.4–52.4 | 42.97 | 42.1 | -/96.8 |

| 1950 | 257.3 | 256.9 | 92.0–94.2 | 219.0 | 80.2 | 279.1/273.1 |

| 1960 | 286.3 | 290.5 | 53.6–56.0 | 236.8 | 45.6 | 535.1/518.9 |

| 1970 | 370.9 | 380.9 | 35.4–37.6 | 283.2 | 28.0 | 1,049/1,013 |

| 1980 | 907.7 | 909.0 | 32.4–33.4 | 711.9 | 26.1 | 2,796/2,724 |

| 1990 | 3,233 | 3,206 | 54.2–56.4 | 2,412 | 42.1 | 5,915/5,735 |

| 2000 | (a1) 5,674 | 5,629 | a55.8/57.6 | 3,410 | 34.7 | 10,150/9,821 |

| 2001 | (a2) 5,807 | 5,770 | a54.8/56.6 | 3,320 | 32.5 | 10,570/10,230 |

| 2002 | (a3) 6,228 | 6,198 | a57.2/59.0 | 3,540 | 33.6 | 10,880/10,540 |

| 2003 | (a) 6,783 | 6,760 | a 59.8/61.8 | 3,913 | 35.6 | 11,330/10,980 |

| 2004 | (a) 7,379 | 7,355 | a 61.0/63.2 | 4,296 | 36.8 | 12,090/11,680 |

| 2005 | (a4) 7,933 | 7,905 | a 61.4/63.8 | 4,592 | 36.9 | 12,890/12,430 |

| 2006 | (a5) 8,507 | 8,451 | a 62.0/64.4 | 4,829 | 36.5 | 13,690/13,210 |

| 2007 | (a6) 9,008 | 8,951 | a 62.8/64.8 | 5,035 | 36.2 | 14,320/13,860 |

| 2008 | (a7) 10,025 | 9,986 | a 67.8/69.8 | 5,803 | 40.2 | 14,760/14,330 |

| 2009 | (a8) 11,910 | 11,876 | a 82.6/85.2 | 7,552 | 53.6 | 14,410/13,960 |

| 2010 | (a9) 13,562 | 13,529 | a 91.6/94.4 | 9,023 | 62.2 | 14,790/14,350 |

| 2011 | (a10) 14,790 | 14,764 | a 96.0/99.0 | 10,127 | 15,390/14,930 | |

| 2012 | (a11) 16,066 | 16,051 | a 99.8/103.2 | 11,270 | 16,090/15,550 | |

| 2013 | (a12) 16,738 | 16,719 | a 100.6/- | 16,630/- | ||

| 2014 (Oct. '13- Jun. '14) |

~17,633 | ~ |

On June 25, 2014, the BEA announced: "[On July 30, 2014, i]n addition to the regular revision of estimates for the most recent 3 years and for the first quarter of 2014, GDP and select components will be revised back to the first quarter of 1999.

Fiscal years 1940–2009 GDP figures were derived from February 2011 Office of Management and Budget figures which contained revisions of prior year figures due to significant changes from prior GDP measurements. Fiscal years 1950–2010 GDP measurements were derived from December 2010 Bureau of Economic Analysis figures which also tend to be subject to revision, especially more recent years. Afterwards the OMB figures were revised back to 2004 and the BEA figures (in a revision dated July 31, 2013) were revised back to 1947.

Absolute differences from advance (one month after) BEA reports of GDP percent change to current findings (as of November 2013) found in revisions are stated to be 1.3% ± 2.0% or a 95% probability of being within the range of 0.0–3.3%, assuming the differences to occur according to standard deviations from the average absolute difference of 1.3%. E.g. with an advance report of a $400 billion increase of a $10 trillion GDP, for example, one could be 95% confident that the range would be 0.0 to 3.3% different than 4.0% (400 ÷ 10,000) or $0 to $333 billion different than the hypothetical $400 billion.

Fiscal years 1940–1970 begin July 1 of the previous year (for example, Fiscal Year 1940 begins July 1, 1939 and ends June 30, 1940); fiscal years 1980–2010 begin October 1 of the previous year.

Intergovernmental debts before the Social Security Act are presumed to equal zero.

1909–1930 calendar year GDP estimates are from MeasuringWorth.com[110] Fiscal Year estimates are derived from simple linear interpolation.

(a1) Audited figure was "about $5,659 billion."[111]

(a2) Audited figure was "about $5,792 billion."[112]

(a3) Audited figure was "about $6,213 billion."[112]

(a) Audited figure was said to be "about" the stated figure.[113]

(a4) Audited figure was "about $7,918 billion."[114]

(a5) Audited figure was "about $8,493 billion."[114]

(a6) Audited figure was "about $8,993 billion."[115]

(a7)Audited figure was "about $10,011 billion."[115]

(a8) Audited figure was "about $11,898 billion."[116]

(a9) Audited figure was "about $13,551 billion."[117]

(a10) GAO affirmed Bureau of the Public debt figure as $14,781 billion.[118]

(a11) GAO affirmed Bureau of the Public debt figure as $16,059 billion.[118]

(a12) GAO affirmed Bureau of the Public debt figure as $16,732 billion.[119]

Interest Paid

| Year | Historical Debt Outstanding, US$[120] | Interest paid[121] | Interest rate |

| 2013 | 17,023,234,543,635.67 | $415,668,781,248.40 | 2.44% |

| 2012 | 16,066,241,407,385.80 | $359,796,008,919.49 | 2.24% |

| 2011 | 14,790,340,328,557.10 | $454,393,280,417.03 | 3.07% |

| 2010 | 13,561,623,030,891.70 | $413,954,825,362.17 | 3.05% |

| 2009 | 11,909,829,003,511.70 | $383,071,060,815.42 | 3.22% |

| 2008 | 10,024,724,896,912.40 | $451,154,049,950.63 | 4.50% |

| 2007 | 9,007,653,372,262.48 | $429,977,998,108.20 | 4.77% |

| 2006 | 8,506,973,899,215.23 | $405,872,109,315.83 | 4.77% |

| 2005 | 7,932,709,661,723.50 | $352,350,252,507.90 | 4.44% |

| 2004 | 7,379,052,696,330.32 | $321,566,323,971.29 | 4.36% |

| 2003 | 6,783,231,062,743.62 | $318,148,529,151.51 | 4.69% |

| 2002 | 6,228,235,965,597.16 | $332,536,958,599.42 | 5.34% |

| 2001 | 5,807,463,412,200.06 | $359,507,635,242.41 | 6.19% |

| 2000 | 5,674,178,209,886.86 | $361,997,734,302.36 | 6.38% |

| 1999 | 5,656,270,901,615.43 | $353,511,471,722.87 | 6.25% |

| 1998 | 5,526,193,008,897.62 | $363,823,722,920.26 | 6.58% |

| 1997 | 5,413,146,011,397.34 | $355,795,834,214.66 | 6.57% |

| 1996 | 5,224,810,939,135.73 | $343,955,076,695.15 | 6.58% |

| 1995 | 4,973,982,900,709.39 | $332,413,555,030.62 | 6.68% |

| 1994 | 4,692,749,910,013.32 | $296,277,764,246.26 | 6.31% |

| 1993 | 4,411,488,883,139.38 | $292,502,219,484.25 | 6.63% |

| 1992 | 4,064,620,655,521.66 | $292,361,073,070.74 | 7.19% |

| 1991 | 3,665,303,351,697.03 | $286,021,921,181.04 | 7.80% |

Foreign holders of US Treasury securities

The following is a list of the top foreign holders (over $75 billion) of US Treasury securities as listed by the US Treasury (revised by April 2014 survey):[122]

| Leading foreign holders of US Treasury securities as of April 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic area | Billions of dollars (est.) | Ratio of owned US debt to GDP (est.)[123][124] |

Percent change since April 2013 |

| Mainland China | 1,263.2 | 9% | - 2.1% |

| Japan | 1,209.7 | 24% | + 8.7% |

| Belgium | 366.4 | 72% | +97.5% |

| Caribbean Banking Centers1 | 308.4 | n/a | + 8.2% |

| Oil exporters2 | 255.5 | n/a | - 6.0% |

| Brazil | 245.8 | 11% | - 2.9% |

| British Islands3 | 185.5 | 7% | +15.8% |

| Switzerland | 177.6 | 27% | - 4.4% |

| Taiwan | 175.7 | 36% | - 5.4% |

| Hong Kong | 155.1 | 57% | + 9.8% |

| Luxembourg | 141.3 | 233% | - 5.6% |

| Russia | 116.4 | 6% | -22.1% |

| Ireland | 112.1 | 51% | - 7.0% |

| Singapore | 93.1 | 31% | + 0.9% |

| Norway | 85.6 | 17% | +14.3% |

| Others | 1,069.6 | n/a | + 1.7% |

| Grand total | 5,960.9 | n/a | + 4.4% |

1Caribbean Banking Centers are Cayman Islands, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Bahamas, Netherlands Antilles, and Panama

2Oil exporters are Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Iraq, Algeria, Qatar, Kuwait, Ecuador, Oman, Libya, Bahrain, and Gabon

3British Islands are United Kingdom, Guernsey, Jersey, and Isle of Man

Statistics

- U.S. official gold reserves, totaling 275.0 million troy ounces, have a book value as of 31 December 2010[update] of approximately $11.6 billion,[125] vs. a commodity value as of 23 January 2011[update] of approximately $445 billion.[126]

- Foreign exchange reserves $133 billion as of December 2010[update].[127]

United States balance of trade (1980–2012), with negative numbers denoting a trade deficit - The Strategic Petroleum Reserve had a value of approximately $65 billion as of January 2011[update], at a Market Price of $98/barrel with a $15/barrel discount for sour crude.[128]

- The national debt equates to $44,900 per person U.S. population, or $91,500 per member of the U.S. working population,[129] as of December 2010.

- In 2008, $242 billion was spent on interest payments servicing the debt, out of a total tax revenue of $2.5 trillion, or 9.6%. Including non-cash interest accrued primarily for Social Security, interest was $454 billion or 18% of tax revenue.[115]

- Total U.S. household debt, including mortgage loan and consumer debt, was $11.4 trillion in 2005. By comparison, total U.S. household assets, including real estate, equipment, and financial instruments such as mutual funds, was $62.5 trillion in 2005.[130]

- Total U.S Consumer Credit Card revolving credit was $931.0 billion in April 2009.[131]

- Total third world debt was estimated to be $1.3 trillion in 1990.[132]

- The U.S. balance of trade deficit in goods and services was $725.8 billion in 2005.[133]

- According to a retrospective Brookings Institute study published in 1998 by the Nuclear Weapons Cost Study Committee (formed in 1993 by the W. Alton Jones Foundation), the total expenditures for U.S. nuclear weapons from 1940 to 1998 was $5.5 trillion in 1996 Dollars.[134] The total public debt at the end of fiscal year 1998 was $5,478,189,000,000 in 1998 Dollars[135] or $5.3 trillion in 1996 Dollars. The entire public debt in 1998 was therefore attributable to the research, development, and deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons-related programs during the Cold War.[134][136][137]

- The global market capitalization for all stock markets that are members of the World Federation of Exchanges was $32.5 trillion by the end of 2008.[138]

- According to the U.S. Department of Treasury Preliminary Annual Report on U.S. Holdings of Foreign Securities, released on August 31, 2012, the United States valued its portfolio at $6.5 trillion, with $4.5 trillion in liquid foreign equities, and $2.4 trillion in long and short term foreign debt. The largest debtors are the United Kingdom, Canada, Cayman Islands, and Australia, whom account for $1.15 trillion owed to the U.S. Treasury.[139]

International debt comparisons

| Entity | 2007 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 62% | 92% | 102% |

| European Union | 59% | 80% | 83% |

| Austria | 62% | 78% | 72% |

| France | 64% | 82% | 86% |

| Germany | 65% | 82% | 81% |

| Sweden | 40% | 39% | 38% |

| Finland | 35% | 48% | 49% |

| Greece | 104% | 123% | 165% |

| Romania | 13% | 31% | 33% |

| Bulgaria | 17% | 16% | 16% |

| Czech Republic | 28% | 38% | 41% |

| Italy | 112% | 119% | 120% |

| Netherlands | 52% | 77% | 65% |

| Poland | 51% | 55% | 56% |

| Spain | 42% | 68% | 68% |

| United Kingdom | 47% | 80% | 86% |

| Japan | 167% | 197% | 204% |

| Russia | 9% | 12% | 10% |

| Asia 1 | 37% | 40% | 41% |

| Latin America 2 | 41% | 37% | 35% |

Sources: Eurostat,[140][dead link] International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook (emerging market economies); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Economic Outlook (advanced economies)[141]

1China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand

2Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico

Recent additions to the public debt of the United States

| Fiscal year (begins Oct. 1 of year prior to stated year) |

GDP $Billions |

Value of yrly debt increase $Billions |

% of GDP | Total debt $Billions |

% of GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | $7,200 | $281–292 | 3.9–4.1% | ~$4,650 | 64.6–65.2% |

| 1995 | 7,600 | 277–281 | 3.7% | ~4,950 | 64.8–65.6% |

| 1996 | 8,000 | 251–260 | 3.1–3.3% | ~5,200 | 65.0–65.4% |

| 1997 | 8,500 | 188 | 2.2% | ~5,400 | 63.2–63.8% |

| 1998 | 8,950 | 109–113 | 1.2–1.3% | ~5,500 | 61.2–61.8% |

| 1999 | 9,500 | 127–130 | 1.3–1.4% | 5,656 | 59.3% |

| 2000 | $10,150 | 18 | 0.2% | 5,674 | 55.7% |

| 2001 | 10,550 | 133 | 1.3% | 5,792 | 54.8% |

| 2002 | 10,900 | 421 | 3.9% | 6,213 | 57.1% |

| 2003 | 11,350 | 570 | 5.0% | 6,783 | 59.8% |

| 2004 | 12,100 | 596 | 4.9% | 7,379 | 61.0% |

| 2005 | 12,900 | 539 | 4.2% | 7,918 | 61.4% |

| 2006 | 13,700 | 575 | 4.2% | 8,493 | 62.1% |

| 2007 | 14,300 | 500 | 3.5% | 8,993 | 62.8% |

| 2008 | 14,750 | 1,018 | 6.9% | 10,011 | 67.8% |

| 2009 | 14,400 | 1,887 | 13.1% | 11,898 | 82.5% |

| 2010 | 14,800 | 1,653 | 11.2% | 13,551 | 91.6% |

| 2011[142] | 15,400 | 1,230 | 8.0% | 14,781 | 96.1% |

| 2012 | 16,100 | 1,278 | 7.9% | 16,059 | 99.8% |

| 2013 | 16,650 | 673 | 4.0% | 16,732 | 100.6% |

| 2014 (Oct.'13- Mar.'14 only) |

~869 | ~5.1% | ~17,601 | ~104.0% |

The more precise FY 1999–2013 debt figures are derived from Treasury audit results.

The variations in the 1990s and FY 2014 figures are due to double-sourced or relatively preliminary GDP figures respectively.

A comprehensive revision GDP revision dated July 31, 2013 was described on the Bureau of Economic

Analysis website. In November 2013 the total debt and yearly debt as a percentage of GDP columns of this table were

changed to reflect those revised GDP figures.

Historical debt ceiling levels

| Table of historical debt ceiling levels[143] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Debt Ceiling (billions of dollars) |

Change in Debt Ceiling (billions of dollars) |

Statute |

| June 25, 1940 | 49[144] | ||

| February 19, 1941 | 65 | +16 | |

| March 28, 1942 | 125 | +60 | |

| April 11, 1943 | 210 | +85 | |

| June 9, 1944 | 260 | +50 | |

| April 3, 1945 | 300 | +40 | |

| June 26, 1946 | 275 | −25 | |

| August 28, 1954 | 281 | +6 | |

| July 9, 1956 | 275 | −6 | |

| February 26, 1958 | 280 | +5 | |

| September 2, 1958 | 288 | +8 | |

| June 30, 1959 | 295 | +7 | |

| June 30, 1960 | 293 | −2 | |

| June 30, 1961 | 298[145] | +5 | |

| July 1, 1962 | 308 | +10 | |

| March 31, 1963 | 305 | −3 | |

| June 25, 1963 | 300 | −5 | |

| June 30, 1963 | 307 | +7 | |

| August 31, 1963 | 309 | +2 | |

| November 26, 1963 | 315 | +6 | |

| June 29, 1964 | 324 | +9 | |

| June 24, 1965 | 328 | +4 | |

| June 24, 1966 | 330 | +2 | |

| March 2, 1967 | 336 | +6 | |

| June 30, 1967 | 358 | +22 | |

| June 1, 1968 | 365 | +7 | |

| April 7, 1969 | 377 | +12 | |

| June 30, 1970 | 395 | +18 | |

| March 17, 1971 | 430 | +35 | |

| March 15, 1972 | 450[146] | +20 | |

| October 27, 1972 | 465 | +15 | |

| June 30, 1974 | 495 | +30 | |

| February 19, 1975 | 577 | +82 | |

| November 14, 1975 | 595 | +18 | |

| March 15, 1976 | 627 | +32 | |

| June 30, 1976 | 636 | +9 | |

| September 30, 1976 | 682 | +46 | |

| April 1, 1977 | 700 | +18 | |

| October 4, 1977 | 752 | +52 | |

| August 3, 1978 | 798 | +46 | |

| April 2, 1979 | 830 | +32 | |

| September 29, 1979 | 879[147] | +49 | |

| June 28, 1980 | 925 | +46 | |

| December 19, 1980 | 935 | +10 | |

| February 7, 1981 | 985 | +50 | |

| September 30, 1981 | 1,079 | +94 | |

| June 28, 1982 | 1,143 | +64 | |

| September 30, 1982 | 1,290 | +147 | |

| May 26, 1983 | 1,389 | +99 | Pub. L. 98–34 |

| November 21, 1983 | 1,490 | +101 | Pub. L. 98–161 |

| May 25, 1984 | 1,520 | +30 | |

| June 6, 1984 | 1,573 | +53 | Pub. L. 98–342 |

| October 13, 1984 | 1,823 | +250 | Pub. L. 98–475 |

| November 14, 1985 | 1,904 | +81 | |

| December 12, 1985 | 2,079 | +175 | Pub. L. 99–177 |

| August 21, 1986 | 2,111 | +32 | Pub. L. 99–384 |

| October 21, 1986 | 2,300 | +189 | |

| May 15, 1987 | 2,320[148] | +20 | |

| August 10, 1987 | 2,352 | +32 | |

| September 29, 1987 | 2,800 | +448 | Pub. L. 100–119 |

| August 7, 1989 | 2,870 | +70 | |

| November 8, 1989 | 3,123 | +253 | Pub. L. 101–140 |

| August 9, 1990 | 3,195 | +72 | |

| October 28, 1990 | 3,230 | +35 | |

| November 5, 1990 | 4,145 | +915 | Pub. L. 101–508 |

| April 6, 1993 | 4,370 | +225 | |

| August 10, 1993 | 4,900 | +530 | Pub. L. 103–66 |

| March 29, 1996 | 5,500 | +600 | Pub. L. 104–121 (text) (PDF) |

| August 5, 1997 | 5,950 | +450 | Pub. L. 105–33 (text) (PDF) |

| June 11, 2002 | 6,400[149] | +450 | Pub. L. 107–199 (text) (PDF) |

| May 27, 2003 | 7,384 | +984 | Pub. L. 108–24 (text) (PDF) |

| November 16, 2004 | 8,184[149] | +800 | Pub. L. 108–415 (text) (PDF) |

| March 20, 2006 | 8,965[150] | +781 | Pub. L. 109–182 (text) (PDF) |

| September 29, 2007 | 9,815 | +850 | Pub. L. 110–91 (text) (PDF) |

| June 5, 2008 | 10,615 | +800 | Pub. L. 110–289 (text) (PDF) |

| October 3, 2008 | 11,315[151] | +700 | Pub. L. 110–343 (text) (PDF) |

| February 17, 2009 | 12,104[152] | +789 | Pub. L. 111–5 (text) (PDF) |

| December 24, 2009 | 12,394 | +290 | Pub. L. 111–123 (text) (PDF) |

| February 12, 2010 | 14,294 | +1,900 | Pub. L. 111–139 (text) (PDF) |

| January 30, 2012 | 16,394 | +2,100 | |

| May 19, 2013 | 16,700 | +306 | |

See also

- Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

- List of countries by public debt

- Sovereign default

- Troubled Asset Relief Program

References

- ^ "Federal debt basics – How large is the federal debt?". Government Accountability Office. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "Historical Tables – Table 1.2 – Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-) as Percentages of GDP: 1930–2017" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ About 0.8% of debt ($79 billion) is not covered by the ceiling, per The Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases, p 4. This includes pre-1917 debt.

- ^ "Federal Debt: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions". Government Accountability Office. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ Debt to the Penny - Treasury Direct

- ^ a b BEA-Gross Domestic Product

- ^ a b c Debt to the Penny - Treasury Direct

- ^ U.S. Treasury-Data Chart Center-Retrieved April 2012

- ^ a b Debt to the Penny (Daily History Search Application)

- ^ Social Security Trustees Report-2012

- ^ "Social Security Trust Fund 2010 Report Summary". Ssa.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "Federal debt basics – What is the difference between the two types of federal debt?". Government Accountability Office. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "Measuring the Deficit: Cash vs. Accrual". Government Accountability Office. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac to Be Kept Off Budget, White House Says (September 12, 2008), bloomberg.com.

- ^ The case for keeping Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac off the government's books has gotten even weaker, professional.wsj.com (subscription required)

- ^ Barr, Colin (September 7, 2008). "Paulson readies the 'bazooka'". CNNMoney. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ Timiraos, Nick (March 3, 2014). "Investor Fires Salvo Against Fannie, Freddie-Viewed March 2014". WSJ. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Congress of the United States, Government Accountability Office (February 13, 2009). "The federal government's financial health: a citizen's guide to the 2008 financial report of the United States government", pp. 7–8. United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) [website]. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ Peter G. Peterson Foundation (April 2010). "Citizen's guide 2010: Figure 10 Page 16". Peter G. Peterson Foundation [website]. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ CBO – The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022 – See Historical Budget Data Supplement – January 2012

- ^ CIA World Factbook-United States – Retrieved January 14, 2013

- ^ [1] OECD Statistics – National Accounts, retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b US national debt surpasses $16 trillion – Boston Business Journal

- ^ a b United States Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Public Debt (December 2010). "The debt to the penny and who holds it". TreasuryDirect. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Table 1.1 – Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-): 1789–2017 Whitehouse.gov

- ^ OMB, Historical Statistics, Table 7.1.

- ^ "Treasurydirect.gov". Treasurydirect.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Saint Louis Federal Reserve (2012) "5-Year Treasury Inflation-Indexed Security, Constant Maturity" FRED Economic Data chart from government debt auctions (the x-axis at y=0 represents the inflation rate over the life of the security)

- ^ a b Carmen M. Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia (March 2011) "The Liquidation of Government Debt" National Bureau of Economic Research working paper No. 16893

- ^ David Wessel (August 8, 2012) "When Interest Rates Turn Upside Down" Wall Street Journal (full text)

- ^ Lawrence Summers (June 3, 2012) "Breaking the negative feedback loop" Reuters

- ^ Matthew Yglesias (May 30, 2012) "Why Are We Collecting Taxes?" Slate

- ^ William H. Gross (May 2, 2011) "The Caine Mutiny (Part 2)" PIMCO Investment Outlook

- ^ "Why the U.S. Government Never, Ever Has to Pay Back All Its Debt" The Atlantic, February 1, 2013

- ^ Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (October 21, 2012) "IMF's epic plan to conjure away debt and dethrone bankers" The Telegraph

- ^ Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof (August 2012) "The Chicago Plan Revisited" International Monetary Fund working paper WP/12/202

- ^ "Debt-Deflation versus the Liquidity Trap: the Dilemma of Nonconventional Monetary Policy" CNRS, CES, Paris School of Economics, ESCP-Europe, October 23, 2012

- ^ "Credit and debt in Economic Theory: Which Way forward?" “Economics of Credit and Debt workshop, November 2012

- ^ "The economic crisis: How to stimulate economies without increasing public debt", Centre for Economic Policy Research, August 2012

- ^ "Public Debt Acts: Major Acts of Congress". Enotes.com. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ "A Brief History of the U.S. Federal Debt Limit". Freegovreports.com. January 28, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Government Accountability Office (February 22, 2011). "Debt Limit: Delays Create Debt Management Challenges and Increase Uncertainty in the Treasury Market".

- ^ Lowrey, Annie (May 16, 2011). "Debt ceiling crisis: The debt ceiling is a pointless, dangerous relic, and it should be abolished". Slate. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ Epstein, Jennifer (July 18, 2011). "Moody's: Abolish the debt limit". Politico. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ Gail Russell Chaddock (January 4, 2010). "Repeal of the Gephardt rule". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Timothy Geithner (April 4, 2011). "Geithner Letter to Congress". Treasury Department.

- ^ "U.S. National Debt Tops Debt Limit". CBS News. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c "2014 TNT 16-23 LEW URGES CONGRESS TO RAISE DEBT LIMIT BEFORE FEBRUARY 7". Tax Notes Today by Tax Analysts( (2014 TNT 16-23). January 2014.

- ^ "Table 7.3 - Statutory Limits on Federal Debt: 1940–Current". Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ Simon Rodgers (January 3, 2012). "US debt ceiling: how big is it and how has it changed?". the guardian.

- ^ H.J.Res. 45

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status – 111th Congress (2009–2010) – H.J.RES.45 – CRS Summary – THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. February 4, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ Spetalnick, Matt (February 12, 2010). "Obama signs debt limit-paygo bill into law". Reuters. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ Senate sinks debt-ceiling disapproval bill

- ^ Koba, Mark. "What is the 'Fiscal Cliff?'". CNBC.com. CNBC.com. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ "Treasury Direct-Monthly Statement of the Public Debt Held by the U.S.-January 2011" (PDF). Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Treasury-Foreign Holdings of U.S. Debt-As of January 2012". Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ China, Japan, Brazil, Taiwan, Switzerland, Russia, and the United Kingdom holding respectively approximately $1.16 trillion, $1.08 trillion, $230 billion, $178 billion, $145 billion, $143 billion, and $142 billion as of January 2012[update].[57]

- ^ Amadeo, Kimberly (January 10, 2011). "The U.S. debt and how it got so big". About.com. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- ^ Schoen, John W. (March 4, 2007) "Just who owns the U.S. national debt?" MSNBC.com. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities". U.S. Department of Treasury. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ "Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities". U.S. Department of Treasury. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ Whitehouse, Steve (June 30, 2008). "BIS says global downturn could be 'deeper and more protracted' than expected". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2011-Thomson Financial News

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ tf.TFN-Europe_newsdesk (May 20, 2007). "Kuwait pegs dinar to basket of currencies". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2011-AFX News

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)[dead link] - ^ Fattah, Zainab and Brown, Matthew (June 4, 2007). "Syria to end dollar peg, 2nd Arab country in 2 weeks (update3)". Bloomberg. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "IMF takes up gold sales to expand lending" (September 18, 2009) NewsLibrary.com. Retrieved January 22, 2011 (archived; $1.50 charge to view article).

- ^ "China won't dump US Treasuries or pile into gold". China Daily eClips. July 7, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (January 1, 2012). "Nobody Understands Debt". New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ CBO-An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: fiscal years 2012 to 2022-Table 1-6-August 2012

- ^ Orzag, Peter R. (June 17, 2008). "The long-term budget outlook and options for slowing the growth of health care costs". Testimony: Statement of Peter R. Orzag, Director, before the Committee on Finance United States Senate. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ a b "GAO-08-446CG U.S. Financial Condition and Fiscal Future Briefing, presented by the Honorable David M. Walker, Comptroller General of the United States: The National Press Foundation, Washington, D.C.: January 17, 2008" (PDF). Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "The Nation's Long-Term Fiscal Outlook: September 2008 Update". Gao.gov. September 29, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ CBO-The Long-Term Budget Outlook-June 2012

- ^ a b CBO-The Budget and Economic Outlook-August 2011

- ^ a b Huntley, Jonathan (July 27, 2010). "Federal debt and the risk of a fiscal crisis". Congressional Budget Office: Macroeconomic Analysis Division. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Goldman, David (November 16, 2009). "CNNMoney.com's bailout tracker". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Lynch, David J. (March 21, 2013). "Economists See No Crisis With U.S. Debt as Economy Gains". Bloomberg. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ U.S. House of Representatives Republican Caucus (May 27, 2010). "The perils of rising government debt". Republican Caucus Committee on the Budget [website]. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Herndon, Thomas. "Herndon Responds To Reinhart Rogoff". Business Insider. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Weisenthal, Joe. "Reinhart And Rogoff Admit Excel Blunder". Business Insider. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Herndon, Thomas, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin, "Does High Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of Reinhart and Rogoff," University of Massachusetts – Amherst Department of Economics, April 15, 2013.

- ^ FT Data, "Reinhart-Rogoff recrunch the numbers," April 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (May 27, 2010). "Bad analysis at the deficit commission". The New York Times: The Opinion Pages: Conscience of a Liberal Blog. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Vikas Bajaj (April 17, 2013) "Does High Debt Cause Slow Growth?", The New York Times Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Matthew O'Brien, "Forget Excel: This Was Reinhart and Rogoff's Biggest Mistake", The Atlantic

- ^ NYT-Binyamin Appelbaum-Predicting a Crisis, Repeatedly-February 22, 2013

- ^ Greenlaw, Hamilton, Hooper, Mishkin Crunch Time: Fiscal Crises and the Role of Monetary Policy-February 2013

- ^ The Atlantic-No, the United States Will Never, Ever Turn Into Greece-Mathew O'Brien-March 7, 2013

- ^ Bernanke, Ben S. (April 27, 2010). "Speech before the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform: Achieving fiscal sustainability". Federalreserve.gov. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Bittle, Scott & Johnson, Jean (2008). Where Does the Money Go? New York: Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-124187-1.

- ^ Bernanke, Ben S. (October 4, 2006). "The coming demographic transition: Will we treat future generations fairly?" Federalreserve.gov. Retrieved February 3, 2011

- ^ Court, Andy (July 8, 2007). "U.S. heading for financial trouble?". CBS News. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ a b United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (December 17, 2007). FY 2007 Financial Report of the U.S. Government, p. 47, et al. www.gao.gov. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ Greenspan, Alan (June 18, 2010). "U.S. Debt and the Greece analogy". Opinion Journal [online]. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ GAO-Financial Audit-Bureau of the Public Debt’s Fiscal Years 2012 and 2011 Schedules of Federal Debt-November 2012

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (November 3, 2009). "Interview with Charlie Rose". Charlie Rose [website]. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Horney, James R. (May 27, 2010). "Recommendation that president’s fiscal commission focus on gross debt is misguided". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities [website]. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ United States Treasury, Bureau of the Public Debt (April 30, 2010). "Monthly statement of public debt of the United States". TreasuryDirect. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ "CBO-Social Security Policy Options-July 2010" (PDF). Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ WSJ-A Short Primer on the National Debt-John Steele Gordon-August 2011

- ^ a b NYT-Paul Krugman-Debt is Mostly Money We Owe Ourselves-December 2011

- ^ Professor G. William Domhoff-Who Rules America?-Sociology Department-University of California Santa Cruz-Retrieved March 2013

- ^ Dean Baker-Center for Economic and Policy Research-David Brooks is Projecting His Self Indulgence Again-December 2011

- ^ NYT-Paul Krugman-Cheating our Children-March 2013

- ^ a b United States Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Public Debt (2010). "Government – Historical Debt Outstanding – Annual". TreasuryDirect. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b The Executive Office of the President of the United States, Office of Management and Budget (April 10, 2013). "Federal debt at the end of year: 1940–2018"; "Gross domestic product and deflators used in the historical tables: 1940–2018" Budget of the United States Government: Fiscal Year 2014: Historical Tables, pp. 143–144, 215–216. Government Printing Office [website]. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ The Executive Office of the President of the United States, Office of Management and Budget (February 14, 2010). "Historical Tables: Table 7-1; 10-1", The White House. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ a b United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. "National Economic Accounts: Gross Domestic Product: Current-dollar and 'real' GDP". BEA.gov. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ Frank H. Vizetelly, Litt.D., LL.D., ed. (1999). "DEBT, National". New Standard Encyclopedia of Universal Knowledge. Vol. Eight. "New York and London": Funk and Wagnalls Company. p. 471.

Debt of Principal Nations and Aggregate for All Nations of the World at Various Dates (in millions of dollars): '1928........18,510'

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ MeasuringWorth.com (December 14, 2010) "What was the U.S. GDP then?". MeasuringWorth.com. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (March 1, 2001). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2000 and 1999 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-01-389 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ a b United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 1, 2002). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2002 and 2001 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-03-199 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 5, 2004). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2004 and 2003 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-05-116 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 7, 2006). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2006 and 2005 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-07-127 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 7, 2008). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2008 and 2007 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-09-44 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 10, 2009). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2009 and 2008 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-10-88 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 8, 2010). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2010 and 2009 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-11-52 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (November 8, 2012). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2012 and 2011 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-13-114 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ United States Congress, Government Accountability Office (December 12, 2013). Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2012 and 2013 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-14-173 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ TreasuryDirect

- ^ TreasuryDirect

- ^ United States Department of the Treasury and Federal Reserve Board (June 16, 2014) "Major foreign holders of Treasury securities" U.S. Department of the Treasury [website].

- ^ The World Factbook – Field Listing :: GDP (official exchange rate)

- ^ The World Factbook – Field Listing :: GDP (purchasing power parity) for China figures only

- ^ U.S. Department of the Treasury, Financial Management Service (January 13, 2011). "Status report of U.S. Treasury-owned gold". fms.treas.gov. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Goldprice Pty Ltd. (July 29, 2011). "Spot gold price". goldprice.org. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ International Money Fund (January 18, 2011). "Time series data on international reserves and foreign currency liquidity: Official reserve assets". International Monetary Fund [website]. Retrieved January 23, 2011

- ^ United States Department of Energy, Strategic Petroleum Reserve Project Management Office (November 30, 2010). "Strategic petroleum reserve inventory". Strategic Petroleum Reserve [website]. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

^ Hamilton, James (August 21, 2005). "Sweet and sour crude". Econbrowser. Retrieved January 23, 2011. - ^ United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (December 2010) "Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Current News Releases: Employment Situation" Bureau of Labor Statistics [website]. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (March 9, 2006). "Z.1-Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States", p. 8, 102. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System [website]. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (June 5, 2009). "G.19-Consumer Credit". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System [website]. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ Rogoff, Kenneth (1991). "Third World Debt". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563 - ^ United States Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau (February 19, 2006). Archived 2006-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Census Bureau [website]. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Stephen I. (1998). Atomic audit: the costs and consequences of U.S. nuclear weapons since 1940. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 3, 12, 105, 107, 461, 546, 551. ISBN 978-0815777748.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Historical Budget Tables, whitehouse.gov.

- ^ "The peak U.S. inventory was around 35,000 nuclear weapons. The United States spent more than $5.5 trillion on the nuclear arms race, an amount equal to its national debt in 1998..." Graham, Jr., Thomas (2002). Disarmament sketches: three decades of arms control and international law. USA: University of Washington Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0295982120.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "...the total figure will likely be equal to the $5 trillion national debt. In short, one quarter to one third of all military spending since World War II has been devoted to nuclear weapons and their infrastructure..." page 33, Schwartz, Steven I. (November 1995). "Four Trillion Dollars and Counting". Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. 51 (6). Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 32–53. ISSN 0096-3402.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ World Federation of Exchanges (April 2009). WFE Annual Report & Statistics 2008, p. 84. World Federation of Exchanges [website]. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Preliminary Annual Report on U.S. Holdings of Foreign Securities

- ^ Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table

- ^ Cecchetti, Stephen G. et al. (March 2010). "The future of public debt: prospects and implications", p. 3. Bank for International Settlements [website]. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ "The United States enters the twilight zone – MuniLand". Reuters. May 3, 2012.

- ^ "Table 7.1 – Federal Debt at the End of Year: 1940–2016". Historical Tables. Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ "The-privateer.com, 1940–1960". The-privateer.com. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "The-privateer.com, 1961–1971". The-privateer.com. Retrieved May 18, 2011.