History of the Nintendo Entertainment System

The history of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) spans the 1982 development of the Family Computer, to the 1985 launch of the NES, to Nintendo's rise to global dominance based upon this platform throughout the late 1980s. The Family Computer (Japanese: ファミリーコンピュータ, Hepburn: Famirī Konpyūta) or Famicom (ファミコン, Famikon) was developed in 1982 and launched in 1983 in Japan. Following the North American video game crash of 1983, the Famicom was adapted into the NES which was launched in North America in 1985. Transitioning the company from its arcade game history into this combined global 8-bit home video game console platform, the Famicom and NES continued to aggressively compete with next-generation 16-bit consoles, including the Sega Genesis. The platform was succeeded by the Super Famicom in 1990 and the Super Nintendo Entertainment System in 1991, but its support and production continued until 1995. Interest in the NES has been renewed by collectors and emulators, including Nintendo's own Virtual Console platform.

1981–1984: Origins

[edit]1981–1983: Development

[edit]The video game industry experienced a period of rapid growth and unprecedented popularity during the late 1970s to early 1980s, with the golden age of arcade video games and the second generation of video game consoles: Space Invaders (1978) and its shoot 'em up clones had become a phenomenal success across arcades worldwide,[1] game consoles such as the Atari 2600 and the Intellivision became popular in North American homes, and the Epoch Cassette Vision became the best-selling console in Japan.[2] Many companies, including Nintendo, arose in their wake to exploit the growing industry.

The inspiration for the Famicom hardware was arcade video game hardware. A major influence was Namco's Galaxian (1979), which had replaced the more intensive bitmap rendering system of Space Invaders with a hardware sprite rendering system that animated sprites over a scrolling background, allowing more detailed graphics, faster gameplay, and a scrolling animated starfield background. This provided the basis for Nintendo's Radar Scope (1980) arcade hardware, which they co-developed with Ikegami Tsushinki, improving on Galaxian with technology such as high-speed emitter-coupled logic (ECL) integrated circuit (IC) chips and memory on a 50 MHz printed circuit board. Following the commercial failure of Radar Scope, the game's arcade hardware was converted for use with Donkey Kong (1981), which became a major arcade hit. Home systems at the time were not powerful enough to handle an accurate port of Donkey Kong, so Nintendo wanted to create a system to allow a fully accurate conversion of Donkey Kong to be played in homes.[1]

Led by Masayuki Uemura, Nintendo's R&D2 team began work on a home system in 1982, ambitiously targeted to be less expensive than its competitors, yet with performance that could not be surpassed by its competitors for at least one year.[1] The console began development under the codename Project GAMECOM.[1] Uemura analyzed the innards of rival consoles, including the Atari 2600 and Magnavox Odyssey, sidestepping their primitive technology.[3] Their main competition was the Epoch Cassette Vision, the best-selling console in Japan at the time, with Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi telling employees he wanted them to develop a console both more powerful and cheaper than the Cassette Vision.[2] Nintendo R&D2 engineer Katsuya Nakakawa analyzed the IC chips of the more powerful Donkey Kong arcade hardware, concluding that it would be possible to use them as a basis for their console.[1] Another Nintendo R&D2 engineer, Takao Sawano, proposed that the D-pad of Nintendo's Game & Watch handheld devices should be adapted for the console.[4]

Meanwhile in North America, the toy manufacturer Coleco was working on a new home console to compete with the Atari 2600 and which would be capable of handling fairly accurate ports of arcade games. Coleco demonstrated a prototype of the ColecoVision to Nintendo R&D2 engineers, who were impressed by the smoothly animated graphics. It left a strong impression on Sawano and Uemara, who had the ColecoVision in mind while working on Nintendo's new console in Japan. However, while the ColecoVision was a significant improvement over the Atari 2600, there was still no console comparable to the original Donkey Kong arcade hardware.[4] Nevertheless, the bundled port of Donkey Kong helped the ColecoVision become a major success in North America.[5]

Uemura sent the engineers Katsuya Nakakawa and Masahiro Ootake to meet with Ricoh, a semiconductor manufacturer that had previously worked with Nintendo on arcade games. One of Ricoh's supervisors was Hiromitsu Yagi, a former Mitsubishi Electronics engineer who had previously designed the large-scale integration (LSI) chips for the Nintendo Color TV-Game consoles in the 1970s. To determine the system specifications of the new console, Nakakawa and Masahiro brought along a Donkey Kong arcade machine for Ricoh to analyze, in order to help build a console more powerful than any consoles at the time and which would be comparable to the Donkey Kong arcade hardware.[4]

Uemura initially thought of using a modern 16-bit central processing unit (CPU), but instead settled on an 8-bit CPU based on the inexpensive MOS Technology 6502, supplementing it with a custom graphics chip, the Picture Processing Unit, produced by Ricoh.[6] To reduce costs, suggestions of including a keyboard, modem, and floppy disk drive were rejected, but expensive circuitry was added to provide a versatile 15-pin expansion port connection on the front of the console for future add-on functionality such as peripheral devices. The keyboard, Famicom Modem, and Famicom Disk System would later be released as add-on peripherals, all utilizing the Famicom expansion port. Other peripheral devices connecting via the expansion port would include the Famicom Light Gun, Family Trainer, and various specialized controllers. Many would be released in Japan only, such as the Famicom 3D System and Famicom Disk System.

The wireless broadcast functionality of the TV Tennis Electrotennis (1975) got Nintendo designer Masayuki Uemura to consider adding that capability to the Famicom. He ultimately did not pursue it to keep system costs low.[7]

1983–1984: Famicom release in Japan

[edit]

Nintendo held its own exhibition to unveil the Famicom, becoming a sensation among toy show exhibitors. Shortly after, the competing SG-1000 was unveiled at the Tokyo Toy Show.[8]

Launching on July 15, 1983,[9] the Family Computer (commonly known by the Japanese-English term Famicom) is an 8-bit console using interchangeable cartridges.[6] The Famicom was released in Japan for ¥14,800 (about $150 at the time,[2] or equivalent to $460.00 in 2023). Its launch game list is Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Junior, and Popeye. The console was intentionally designed to look like a toy, with a bright red-and-white color scheme and two hardwired gamepads that are stored visibly at the sides of the unit.

It sold well in its early months,[10] at 500,000 units in its first two months.[11] However, many Famicom units reportedly had faulty graphics chips[12] and froze during gameplay. After tracing the problem to a faulty circuit, Nintendo voluntarily recalled all Famicom systems just before the holiday shopping season, and temporarily suspended production of the system while the concerns were addressed, costing Nintendo millions of dollars. The Famicom was subsequently reissued with a new motherboard.[13] The Famicom easily outsold its primary competitor, the SG-1000. By the end of 1984 Nintendo had sold more than 2.5 million Famicoms in the Japanese market.[14] This made it the best-selling console in Japan, surpassing the Cassette Vision.[2] Sales exceeded Nintendo's expectations, leading to the Famicom being sold out, so Nintendo raised projections and increased production for the following year.[15]

Nintendo had planned to be the exclusive provider of Famicom games during its launch year. Major arcade developer Namco approached Nintendo about Famicom development, as they had no means of cartridge production. They contracted a 30% fee to Nintendo per game sold, consisting of 10% as a licensing fee for the console, and 20% as the production cost of new cartridges. By 1984, third party Famicom games were published. This 30% fee became a de facto standard in console and storefront licensing for video game publishing through the 2010s.[16]

1984–1987: Going international

[edit]1983: Marketing negotiations with Atari

[edit]In the early '80s, Atari debated whether to go with the internally developed successor to the 2600 or a new console that Nintendo wanted us to market. Regrettably, it was my decision not to license the Nintendo system.

—Atari engineer, Steve Bristow[17]

Bolstered by its success in Japan, Nintendo soon turned its attention to foreign markets. As a new console manufacturer, Nintendo had to convince a skeptical public to embrace its system. To this end, Nintendo entered into negotiations with Atari to release the Famicom outside Japan[18] as the Nintendo Enhanced Video System, with plans to release the system by the end of 1983.[19][20] Though the two companies reached a tentative agreement, with final contract papers to be signed at the 1983 Summer Consumer Electronics Show (CES), Atari refused to sign at the last minute, after seeing Coleco, one of its main competitors in the market at that time,[14] demonstrating a prototype of Donkey Kong for its forthcoming Coleco Adam home computer system. Coleco had licensed Donkey Kong for the ColecoVision home console, but Atari had the exclusive computer license for the game. Although the game had been originally produced for the ColecoVision and could thus automatically be played on the backward compatible Adam computer, Atari took the demonstration as a sign that Nintendo was also dealing with Coleco. Though the issue was cleared up within a month, by then Atari's financial problems stemming from the North American video game crash of 1983 coupled with the departure of Atari CEO Ray Kassar left the company unable to follow through with the deal in time to make the target launch.[20][21]

North America

[edit]1984–1986: Nintendo VS. System

[edit]Famicom hardware debuted in North America in the arcades, in the form of the Nintendo VS. System in 1984; the system's success in arcades paved the way for the official release of the NES console.[2][22] After the video game crash of 1983, many American retailers considered video games a passing fad, and greatly reduced or discontinued the inventory of such products.[23] Nintendo of America's market research was met with warnings to stay away from home consoles, with US retailers refusing to stock game consoles. Meanwhile, the arcade industry also had a slump as the golden age of arcade video games came to an end, but arcades were able to recover and stabilize with the help of software conversion kit systems. Hiroshi Yamauchi realized there was still a market for video games in North America, where gamers were gradually returning to arcades in significant numbers. Yamauchi still had faith there was a market for the Famicom, so he decided to introduce it to North America through the arcade industry.[2]

Nintendo developed the VS. System with the same hardware as the Famicom, and introduced it as the successor to its Nintendo-Pak arcade system, which had been used for games such as Donkey Kong 3 and Mario Bros. (both 1983) Though technologically weaker than Nintendo's more powerful Punch-Out arcade hardware, the VS. System was relatively inexpensive, epitomizing Gunpei Yokoi's philosophy of "lateral thinking with withered technology." The VS. System was also able to offer a wider variety of games, due to being able to easily port over games from the Famicom.[2] Upon release, the VS. System generated excitement in the arcade industry, receiving praise for its easy conversions, affordability, flexibility and multiplayer capabilities.[2][24]

The VS. System became a major success in North American arcades.[2] Between 10,000 and 20,000 arcade units were sold in 1984,[25] and individual Vs. games often appeared as top-earners on the US arcade charts,[22] such as VS. Tennis[26][27] and VS. Baseball in 1984,[28][29] then Duck Hunt[2] and VS. Hogan's Alley in 1985.[30] By 1985, 50,000 units had been sold, having established Nintendo as an industry leader in the arcades.[31] The Vs. System went on to become the highest-grossing arcade machine of 1985 in the United States.[32] By the time the NES launched in North America, nearly 100,000 VS. Systems had been sold to American arcades.[33]

The success of the VS. System gave Nintendo the confidence to release the Famicom in North America as a video game console, which would later be called the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Nintendo's strong positive reputation in the arcades generated significant interest in the NES. It also gave Nintendo the opportunity to test new games as VS. Paks in the arcades, to determine which games to release for the NES launch. Nintendo's software strategy was to first release games for the Famicom, then the VS. System, and then for the NES. This allowed Nintendo to build a solid launch line-up for the NES. Many games made their North American debut on the VS. System before releasing for the NES, which led to many players being "amazed" at the accuracy of the arcade "ports" for the NES, though most VS. System games originated on the Famicom.[2]

1985: Advanced Video System home computer

[edit]

Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi said in 1986, "Atari collapsed because they gave too much freedom to third-party developers and the market was swamped with rubbish games."[35] After the deal with Atari failed, Nintendo proceeded alone, re-conceiving the Famicom console with a sophisticated design language as the "Nintendo Advanced Video System" (AVS).[36] To keep the software market for its console from becoming similarly oversaturated, Nintendo added a lockout system to obstruct unlicensed software from running on the console, thus allowing Nintendo to enforce strict licensing standards. The software carries the Nintendo Seal of Quality to communicate the company's approval.

Nintendo's product designer Lance Barr, who would continue with the company for decades, retooled the Famicom console with a sleek and sophisticated design language. The toy-like white-and-red color scheme of the Famicom was replaced with a clean and futuristic color scheme of grey, black, and red. The top and bottom portions are in different shades of grey, plus a stripe with black and ribbing along the top, and minor red accents. The shape is boxier: flat on top, and a bottom half that tapered down to a smaller footprint. The front of the main unit features a compartment for storing the wireless controllers out of sight.[36] To avoid the stigma of video game consoles, Nintendo issued prerelease marketing of the AVS as a full home computer,[37] with an included keyboard, cassette data recorder, and a BASIC interpreter software cartridge.[38] The BASIC interpreter would later be sold together with a keyboard as the Family BASIC package, and the cassette deck for data storage would later be released as the Famicom Data Recorder. The AVS includes a variety of computer-style input devices: gamepads, a handheld joystick, a 3-octave musical keyboard, and the Zapper light gun. The AVS Zapper is hinged, allowing it to straighten out into a wand form, or bend into a gun form. The AVS uses a wireless infrared interface for all its peripherals, including keyboard, cassette deck, and controllers.[39] Most of the peripherals for the Advanced Video System are on display at the Nintendo World Store.[34]

The system's first known advertisement is in Consumer Electronics magazine in 1985, saying "The evolution of a species is now complete."[40] The AVS was showcased at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show held in Las Vegas during January 5–8, 1985,[39][15] in a reportedly "very busy"[39] booth headed by Nintendo of America's president Minoru Arakawa.[36] There, attendees acknowledged the advanced technology, but responded poorly to the keyboard and wireless functionality.[37][41][39][14] All of the more than 25 games[42] demonstrated were complete, with no prototypes.[39] No retail pricing information was given by Nintendo,[39][42] reportedly seeming to "test the waters" with potential distributors, in an unpredictable market.[39]

Although Nintendo of Americas's marketing manager Gail Tilden had reported sales of more than 2.5 million units of the Famicom across the previous 18 months yielding a 90% market share in Japan by the beginning of 1985,[42] the American video game press was skeptical that the AVS could have any success in North America. News Wire reported on January 12, 1985, "It's hard to believe, but a Japanese company says it intends to introduce a new video-game machine in the United States, despite the collapse of the video-game industry here."[42] The March 1985 issue of Electronic Games magazine stated that "the videogame market in America has virtually disappeared" and that "this could be a miscalculation on Nintendo's part".[43] Roger Buoy of Mindscape allegedly said that year, "Hasn't anyone told them that the videogame industry is dead?"[44] Video game historian Chris Kohler reflected, "Retailers didn't want to listen to the little startup Nintendo of America talk about how its Japanese parent company had a huge hit with the Famicom (the system from which the NES was adapted from). In America, videogames were dead, dead, dead. Personal computers were the future, and anything that just played games but couldn't do your taxes was hopelessly backwards."[45] Computer Entertainer openly rebuked the media after attending a humbly optimistic June 1985 Consumer Electronics Show (CES), "Can another video game system buck the trend and become a success? ... Perhaps if the press can avoid jumping all over the Nintendo system and let American consumers make up their own minds, we might find out that video games aren't dead after all."[46]

1985: Redesign as the Nintendo Entertainment System

[edit]

Nintendo really needed to come up with a point of difference, and some way of getting the retailer to believe that the consumer would embrace this as a different and newer form of entertainment. ... We spent a lot of energy not calling it a videogame in any way.

— Gail Tilden, Marketing manager of Nintendo of America[36]

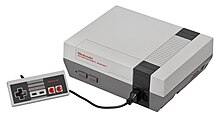

At the 1985 CES, Nintendo returned with a stripped-down and cost-reduced redesign of the AVS, having abandoned the home computer approach.[36] Nintendo purposefully designed the system so as not to resemble a video game console, and would avoid terms associated with game consoles, with marketing manager Gail Tilden choosing the term "Game Pak" for cartridges, "Control Deck" for the console, and "Entertainment System" for the whole platform altogether.[36] Renamed the "Nintendo Entertainment System" (NES), the new and cost-reduced version lacks most of the upscale features added in the AVS, but retains many of its audiophile-inspired design elements, such as the grey color scheme and boxy form factor. Disappointed with the cosmetically raw prototype part they received from Japan, which they nicknamed "the lunchbox", Nintendo of America designers Lance Barr and Don James added the two-tone gray, the black stripe, and the red lettering.[36] To obscure the video game connotation, NES replaced the top-loading cartridge slot of the Famicom and AVS with a front-loading chamber for software cartridges that place the inserted cartridge out of view, reminiscent of a VCR. The Famicom's pair of hard-wired controllers, and the AVS's wireless controllers, were replaced with two custom 7-pin sockets for detachable wired controllers.[37]

Using another approach to market the system to North American retailers as an "entertainment system", as opposed to a video game console, Nintendo positioned the NES more squarely as a toy, emphasizing the Zapper light gun, and more significantly, R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy), a wireless toy robot that responds to special screen flashes with mechanized actions.[23] Although R.O.B. successfully drew a stream of retailers to Nintendo's CES booth to see the NES, they were still unwilling to sign up to distribute the console.[14]

1985–1986: North American launch

[edit]Mr. Arakawa really had this focus ... if it's going to work in New York, it will spread. He always had that sense that if he really believed in something, he really wanted to give it the biggest and best shot.

Gail Tilden, marketing

In a show of strength and confidence by a company that rejected positions of weakness, an intense direct campaign ensued by a dedicated 12-person "Nintendo SWAT team" who relocated from Nintendo of America's headquarters in Redmond.[36][47] The team included Minoru Arakawa, Tukwila warehouse manager and game tester Howard Phillips, Redmond warehouse manager and product designer Don James, product designer Lance Barr, marketer Gail Tilden, her boss Ron Judy, and salesperson Bruce Lowry.[36] Having failed to secure a retail distributor in the last year, the team would deliver the NES debut itself. This began a series of limited test market launches at various metropolitan American cities prior to nationwide release. Instead of the traditional business of test launching at a cheaper mid-sized city, Arakawa boldly chose the nation's largest market, New York City as its initial test market with a $50 million budget.[36] Only with R.O.B's reclassification of the NES as a toy, telemarketing and shopping mall demonstrations, and a risk-free proposition to retailers, did Nintendo secure enough retailer support there of about 500 retailers in New York and New Jersey. As the bellwether and key toy retailer of New York City, the grandest and most important site was a 15 square foot area at FAO Schwarz.[36] This had a dozen playable NES displays surrounding another giant television, featuring Baseball being played by real Major League Baseball players who also signed autographs in order to anchor the curious audiences to a familiar American pastime among all the surreal fantasy games.[48]

In a huge gamble by Arakawa and without having informed the headquarters in Japan, Nintendo offered to handle all store setup and marketing, extend 90 days credit on the merchandise, and accept returns on all unsold inventory. Retailers would pay nothing upfront, and after 90 days would either pay for the merchandise or return it to Nintendo.[45][34] At Nintendo's unprecedented offer of risk absorption,[45] retailers signed up one by one, with one incredulously saying "It's your funeral."[49]

The Nintendo Entertainment System then consisted of the Deluxe Set and an initial library of 17 games which were chosen by Phillips.[50][36][45][48] The Deluxe Set included a Control Deck console, two gamepads, R.O.B., the Zapper light gun, and the Game Paks Gyromite and Duck Hunt.[51] Fifteen additional games were sold separately: 10-Yard Fight, Baseball,[48] Clu Clu Land, Excitebike, Golf, Hogan's Alley, Ice Climber, Kung Fu, Pinball, Soccer, Stack-Up, Super Mario Bros., Tennis, Wild Gunman, and Wrecking Crew.[52][46][45][51][48] The first test launch was in New York City on October 18, 1985, with an initial shipment of 100,000 Deluxe Set systems.[citation needed] Nintendo began marketing the system the same month in October 1985.[53]

Headquartered in a Hackensack warehouse oozing with EPA hazards "something like 'rats and snakes and toxic waste'", the SWAT team worked every day even through Christmas Eve 1985, in what Don James called "the longest and hardest I ever worked consecutive days in my life"[36] and what Phillips called "every waking hour ... at the crack of dawn ... seven days a week".[54] President Arakawa joined them at the warehouse and at retail stores, once running a TV up a flight of stairs just to follow in the whole team's footsteps.[55] While unloading their products into stores, the Nintendo of America crew was confronted by strangers who resented any Japanese-influenced company in a time of international trade issues and cheap Japanese clones of American products. A security guard reportedly said, "You're working for the Japs? I hope you fall flat on your ass."[45] Gail Tilden said, "I remember one woman coming up to me, and I don't know what sparked her to do this, but she came up to me and said, 'Nintendo. That's a Japanese company, right? ... I hope you fail!'". Retail staff resentful of the disastrous video game market rolled their eyes at Nintendo staff, with one manager looking at Nintendo's inventory and saying "Somebody told me I've got to sell this crap." The first sale came soon and quietly, of a Deluxe Set and the 15 additional games, to a gentleman who the team later realized was employed by an unspecified Japanese competitor.[36]

Sales were not high but encouraging throughout the holiday season,[36] though sources vary on how many consoles were sold then.[14][56] In 1986, Nintendo said it had sold nearly 90,000 units in nine weeks during its late 1985 New York City test.[57][58][59] 460,000 game cartridges were also sold in 1985.[53] Following its success in the New York City test market, Nintendo planned to release it gradually across different US states over the first six months of 1986, starting with California at the end of January 1986; Nintendo cited production capacities and other considerations as reasons for the gradual rollout.[60]

In January 1986, an independent research firm commissioned by Nintendo delivered a survey of 200 NES owners, showing that the most popular given reason for buying an NES was because children wanted R.O.B. the robot—followed most strongly by good graphics, variety of games, and the uniqueness and newness of the NES package.[57] R.O.B. is credited as a primary factor in building initial support for the NES in North America,[14][57] but the accessory itself was not well received for its entertainment value. Its original Famicom counterpart, the Famicom Robot, was already failing in Japan at the time of the North American launch.[citation needed] The NES was also credited with bringing arcade-style gaming to homes.[61]

For the nationwide launch in 1986, the NES was available in two different packages: the fully featured US$160[62] Deluxe Set as had been configured during the New York City launch, and a scaled-down US$99 Control Deck package which included the console, two gamepads, and Super Mario Bros.[63][64] In early 1986, Nintendo announced the intention to adapt the Famicom Disk System to the NES by late 1986,[52] but the need was obviated by the proliferation of larger and faster cartridge technology, and the drive's NES launch was canceled and the original was discontinued in Japan by the early 1990s.

Nintendo added Los Angeles as the second test market in February 1986,[36] followed by Chicago and San Francisco,[45] then other top 12 US markets,[65] and finally nationwide in July.[66] Nintendo and Sega, which was similarly exporting its Master System to the US, both planned to spend $15 million in the fourth quarter of 1986 to market their consoles;[35] later, Nintendo said it planned to spend $16 million and Sega said more than $9 million.[59] Nintendo obtained a distribution deal with toymaker Worlds of Wonder, which leveraged its popular Teddy Ruxpin and Lazer Tag products to solicit more stores to carry the NES. From 1986 to 1987, this provided the initially reluctant WoW sales staff with windfall commissions, which Arakawa eventually capped at $1 million per person per year.[50][23] The largest retailer Sears sold it through its Christmas catalog and the second largest retailer Kmart sold it in 700 stores.[59] Nintendo sold 1.1 million consoles in 1986, estimating that it could have sold 1.4 million if inventory had held out.[67] Nintendo earned $310 million in sales, out of total 1986 video game industry sales of $430 million,[68] compared to total 1985 industry sales of $100 million.[69]

It was an easy deal. You just said [to retailers], "Here's your lucky day. I've got an extra 50,000 pieces of NES." Easy sell.

— WoW salesman Steve Race[50]

Europe and Oceania

[edit]The NES was also released in Europe and Australia, in stages and in a rather haphazard manner. It was launched in Scandinavia in September 1986,[70][71] and in the rest of mainland Europe in different months of 1987 (or most likely 1988 in the case of Spain),[72][73] depending on the country. The United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Australia and New Zealand all received the system in 1987, where it was distributed exclusively by Mattel.[74] In Europe, the NES received a less enthusiastic response than it had elsewhere, and Nintendo lagged in market and retail penetration, though the console was more successful later.[75]

During the late 1980s, NES sales were lower than that of the Master System in the United Kingdom.[76] By 1990, the Master System was the highest-selling console in Europe, though the NES was beginning to have a fast growing user base in the United Kingdom.[77] Sega continued outselling Nintendo in the UK into 1992; a reason cited at the time by Paul Wooding of Sega Force was that, "Nintendo became associated with kids playing alone in their rooms, while Sega was first experienced in the arcades with a gang of friends".[78]

Between 1991 and 1992, NES sales were booming in Europe,[79] partly driven by the success of the Game Boy which helped uplift NES sales in the region.[80] By 1994, NES sales had narrowly edged out the Master System overall in Western Europe. Among major European markets, the Master System led in the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Spain, whereas the NES led in France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands.[81] In Australia, the NES was less successful than the Master System.[82]

South Korea

[edit]In South Korea, the hardware was licensed to Hyundai Electronics, which marketed it as the Comboy from 1991. After World War II, the government of Korea (later South Korea) imposed a wide ban on all Japanese "cultural products". Until this was repealed in 1998, the only way Japanese products could legally enter the South Korean market was through licensing to a third-party (non-Japanese) distributor, as was the case with the Comboy and its successor, the Super Comboy, a version of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES).[83]

Hyundai sold 360,000 Comboy units in South Korea by 1993. This was less than half of the Master System (marketed as the Gam*Boy or Aladdinboy by Samsung), at 730,000 units sold in the country by 1993.[84]

Soviet Union and Russia

[edit]After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the introduction of the NES was attempted in two ways. The first was the launch through local distributors.[85][failed verification] The second, much more popular method, was in the form of an unlicensed Taiwanese hardware clone named the Dendy produced in Russia in the early 1990s. Aesthetically, it is a replica of the original Famicom, with a unique color scheme and labels, and with controller ports on the front using DE-9 serial connectors, identical to those used in the Atari 2600 and the Atari 8-bit computers. All Dendy games sold in Russia are bootleg copies, not licensed by Nintendo. In 1994, Nintendo signed an agreement with the Dendy distributor under which Nintendo had no claims against Dendy and allowed the sale of games and consoles.[85][86] A total of 6 million units were sold in Russia and the former Soviet Union.[85]

1987–1990: Leading the industry

[edit]In Japan, about 6.2 million Famicom units had been sold by January 1986, helped by the success of Super Mario Bros. (1985),[87][88] and increased sales to more than 9 million units[89] with 95% of the home video game market by early 1987.[90] In North America, the NES sold 1.1 million units in 1986,[91] out of worldwide sales of 3 million that year.[11] By 1988, the console had sold 12 million units in Japan and was projected to top 10 million in the United States by the end of the year.[92]

The NES widely outsold its primary competitors, the Master System and the Atari 7800. The successful launch of the NES positioned Nintendo to dominate the home video game market for the remainder of the 1980s. Buoyed by the success of the system, NES Game Pak produced similar sales records. The console's library exploded with classic flagship franchise-building and best-selling hits like Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Metroid (both 1986). Toward the 1987 Christmas season, sales of the NES had dwarfed those of Teddy Ruxpin and all other original products of its American distributor, Worlds of Wonder. In October 1987, Minoru Arakawa discontinued the NES distribution contract with the failing WoW in favor of Nintendo's own growing clout, while hiring WoW's sales staff away—the same sales staff previously offered to Nintendo by Atari in 1983.[50]

The Legend of Zelda was the first NES game with over 1 million non-bundled cartridges sold in the United States.[91] At more than 40 million copies, Super Mario Bros. was the highest selling video game in history for many years. Released in 1988 in Japan, Super Mario Bros. 3 would gross more than $500 million, with more than 7 million copies sold in America and 4 million copies in Japan, making it the most popular and fastest selling[93] standalone home video game in history.

By mid-1986, 19% (6.5 million) of Japanese households owned a Famicom;[35] one third by mid-1988.[94] By 1990, over 27 million units were sold in the United States,[95] present in 38% of American households,[96] compared to 23% for all personal computers.[97] The NES had reached a larger user base in the United States than any previous console, surpassing the previous record set by the Atari 2600 in 1982.[98] In 1990, Nintendo also surpassed Toyota as Japan's most successful corporation.[99] By early 1992, more than 40 million units had been sold worldwide,[100] with 30 million in the United States by early 1993.[101]

Its popularity greatly affected the computer-game industry, with executives stating that "Nintendo's success has destroyed the software entertainment market" and "there's been a much greater falling off of disk sales than anyone anticipated". The growth in sales of the Commodore 64 ended; Nintendo sold almost as many consoles in 1988 as the total number of Commodore 64s had been sold in five years. Trip Hawkins called Nintendo "the last hurrah of the 8-bit world",[102] with Nintendo having completely destroyed the Commodore 64 game market as of Christmas 1988.[103]

1990s: Final years

[edit]1990–1992: Market decline

[edit]

In the late 80s, Nintendo's dominance was addressed by newer, technologically superior consoles. In 1987, NEC and Hudson Soft released the PC Engine, and in 1988, Sega released the 16-bit Mega Drive. Both were introduced in North America in 1989, where they were respectively marketed as the TurboGrafx-16 and the Genesis. Facing new competition from the PC Engine in Japan, and the Genesis in North America, Nintendo's market share began to erode. Nintendo responded in the form of the Super Famicom (Super NES or SNES in North America and Europe), the Famicom's 16-bit successor, in 1990. Although Nintendo announced its intention to continue to support the Famicom alongside its newer console, the success of the newer offering began to draw even more gamers and developers from the NES, whose decline accelerated. Nintendo did continue support of the NES for about three years after the September 1991 release of the SNES, with the NES's final first-party games being Zoda's Revenge: StarTropics II and Wario's Woods.

At Christmas 1991, both the NES and SNES were outsold by the Genesis in North America. This led to Nintendo's share of the North American market declining between 1991 and 1992. In contrast, NES sales were then booming in Europe.[79]

1993-1995 New model and Discontinuation in North america

[edit]A revised Famicom (HVC-101 model) was released in Japan in 1993. It takes some design cues from the SNES. The HVC-101 model replaces the original HVC-001 model's RF modulator with RCA composite audio/video output, eliminates the hardwired controllers, and features a more compact case design. Retailing for ¥4,800 to ¥7,200 (equivalent to approximately $42—60), the HVC-101 model remained in production for almost a decade before being finally discontinued in 2003.[104] The case design of the AV Famicom was adopted for a subsequent North American rerelease of the NES. The NES-101 model differs from the Japanese HVC-101 model in that it omits the RCA composite output connectors of the original NES-001 model, and sports only RF output capabilities.[105]

ASCII Entertainment reported in early 1993 that stores still offered 100 NES games, compared to 100 on shelves for Genesis and 50 for SNES.[106] Some of the last games were The incredible crash test dummies,Startropics 2 and Wario's Woods After a decade of production, the NES was formally discontinued on August 14, 1995 with the last game being the lion king.[75][107][108] By the end of its run, more than 60 million NES units had been sold throughout the world.[109]

1995-2003/2007

[edit]A revised Famicom (HVC-101 model) was released in Japan in 1993. It takes some design cues from the SNES. The HVC-101 model replaces the original HVC-001 model's RF modulator with RCA composite audio/video output, eliminates the hardwired controllers, and features a more compact case design. Retailing for ¥4,800 to ¥7,200 (equivalent to approximately $42—60), the HVC-101 model remained in production for almost a decade before being finally discontinued in 2003 and technical support in 2007.[104] The case design of the AV Famicom was adopted for a subsequent North American rerelease of the NES. The NES-101 model differs from the Japanese HVC-101 model in that it omits the RCA composite output connectors of the original NES-001 model, and sports only RF output capabilities.[105]

2007–2018: Emulation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

After the NES's discontinuation, the secondhand market of video rental stores, thrift stores, yard sales, flea markets, and games repackaged by Game Time Inc. / Game Trader Inc. and sold at retail stores such as K-Mart, was burgeoning. Many people began to rediscover the NES around this time, and by 1997 many older NES games were becoming popular with collectors.[citation needed]

At the same time, computer programmers began to develop emulators capable of reproducing the internal workings of the NES on modern personal computers. When paired with a ROM image (a bit-for-bit copy of a NES cartridge's program code), the games can be played on a computer. Emulators also come with a variety of built-in functions that change the gaming experience, such as save states which allow the player to save and resume progress at an exact spot in the game.[citation needed]

Nintendo did not respond positively to these developments and became one of the most vocal opponents of ROM image trading. Nintendo and its supporters claim that such trading represents blatant software piracy.[110] Proponents of ROM image trading argue that emulation preserves many classic games for future generations, outside of their more fragile cartridge formats.[111]

On May 30, 2003, Nintendo announced that it would stop production of the Super Famicom in September, along with discontinuing the original Famicom and software for the Famicom Disk System.[112][113] The last Famicom, serial number HN11033309, was manufactured on September 25;[114][115] it was kept by Nintendo and subsequently loaned to the organizers of Level X, a video game exhibition held from December 4, 2003, to February 8, 2004, at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, for a Famicom retrospective in commemoration of the console's 20th anniversary.[116][117]

In 2005, Nintendo announced plans to publish classic NES games on the Virtual Console download service for the Wii console, which is based on its own emulation technology. Initial games released included Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda and Donkey Kong,[118] with blockbusters such as Super Mario Bros., Punch-Out!!, and Metroid appearing in the following months.[119]

In 2007, Nintendo announced that it would no longer repair Famicom systems, due to an increasing shortage of the necessary parts.[120]

In 2016, Nintendo announced the NES Classic Edition, a dedicated console designed as a miniature replica of the original NES; it features 30 games along with save state capability for each game.[121] It released in Australia on November 10,[122] and in Europe and North America the following day.[121][123] Nintendo also released a Famicom version of the console, featuring a different set of games, in Japan on November 10.[124] The console immediately sold out upon launch due to high demand; intended to be a limited-time release, Nintendo discontinued it in April 2017.[125] Following the release of its successor, the Super NES Classic Edition, the NES Classic Edition was re-released on June 29, 2018; both consoles were discontinued after the end of the holiday season that year.[126][127] As of June 30, 2018, Nintendo has sold 3.6 million units of the NES Classic Edition.[128][129]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "【任天堂「ファミコン」はこうして生まれた】 第6回:業務用ゲーム機の挫折をバネにファミコンの実現に挑む" [How the Famicom Was Born – Part 6: Making the Famicom a Reality]. Nikkei Electronics (in Japanese). Nikkei Business Publications. September 12, 1994. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Making the Famicom a Reality". GlitterBerri's Game Translations. March 28, 2012. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Horowitz, Ken (July 30, 2020). "Nintendo "VS." the World". Beyond Donkey Kong: A History of Nintendo Arcade Games. McFarland & Company. pp. 115–28. ISBN 978-1-4766-4176-8.

- ^ Matt Alt (July 7, 2020). "The Designer Of The NES Dishes The Dirt On Nintendo's Early Days". Kotaku. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c "【任天堂「ファミコン」はこうして生まれた】 第7回:業務用機の仕様を家庭用に、LSIの開発から着手" [How the Famicom Was Born – Part 7: Deciding on the Specs]. Nikkei Electronics (in Japanese). Nikkei Business Publications. December 19, 1994. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Deciding on the Specs". GlitterBerri's Game Translations. April 21, 2012. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012.

- ^ McFerran, Damien (September 18, 2010). "Feature: How ColecoVision Became the King of Kong". Nintendo Life. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Liedholm, Marcus; Liedholm, Mattias. "History of the Nintendo Entertainment System or Famicom". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ "Feature: NES Creator Masayuki Uemura On Building The Console That Made Nintendo A Household Name". Nintendo Life. March 3, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column: Atari, Sega Exhibited Its Home Video Games At The Tokyo Toy Show" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 217. Amusement Press, Inc. August 1, 1983. p. 30.

- ^ "Gaming for 5 to 95". SEC.gov. March 31, 2003. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 15, 2003). "Codename: Famicom". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 7. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004.

- ^ a b Nelson, Murry R. (May 23, 2013). American Sports: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas [4 volumes]: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. p. 1418. ISBN 978-0-313-39753-0.

- ^ Youtube Exclusive: Masayuki Uemura Interview - Designer of the NES. YouTube. TheGebs24. January 28, 2016. Event occurs at 7:48. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Liedholm, Marcus; Liedholm, Mattias. "The Famicom rules the world! – (1983–89)". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldberg, Marty (October 18, 2005). "Nintendo Entertainment System 20th Anniversary". ClassicGaming.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ a b "Overseas Readers Column" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 252. Amusement Press, Inc. January 15, 1985. p. 28.

- ^ Mochizuki, Takahashi; Savov, Vlad (August 25, 2020). "Epic's Battle With Apple and Google Actually Dates Back to Pac-Man". Bloomberg News. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ "Obituary: Gaming pioneer Steve Bristow helped design Tank, Breakout". Ars Technica. February 24, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ Teiser, Don (June 14, 1983). "Interoffice Memo". Retrieved February 12, 2006 – via Atari History Museum.

- ^ "The NES turns 30: How it began, worked, and saved an industry". Ars Technica. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Goldberg, Marty; Vendel, Curt (2012). "Chapter 11". Atari Inc: Business is Fun. Sygyzy Press. ISBN 978-0985597405.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 15, 2003). "Coming to America". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 1, 2004.

- ^ a b Stark, Chelsea (October 19, 2015). "30 years later, Nintendo looks back at when NES came to America". Mashable. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Jeremiah Black (director), Jeff Rubin, Josh Shabtai, Dan Ackerman, Libe Goad, Shandi Sullivan, T. J. Allard (July 13, 2007). Play Value: The Rise of Nintendo (podcast). ON Networks. Archived from the original (Flash Video) on June 20, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Cognevich, Valerie (November 15, 1984). "Nintendo presents new Paks at distributor showing". Play Meter. Vol. 10, no. 21. pp. 24–5.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (July 30, 2020). Beyond Donkey Kong: A History of Nintendo Arcade Games. McFarland & Company. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-4766-4176-8.

More than 10,000 VS. System units were sold by the end of 1984 alone (some put the figure as high as 20,000)

- ^ "RePlay: The Players' Choice". RePlay. July 1984.

- ^ "National Play Meter". Play Meter. August 15, 1984.

- ^ "RePlay: The Players' Choice". RePlay. September 1984.

- ^ "National Play Meter". Play Meter. Vol. 10, no. 21. November 15, 1984. pp. 28–9.

- ^ "RePlay: The Players' Choice". RePlay. Vol. 11, no. 2. November 1985. p. 6.

- ^ "The Vs. Challenge". RePlay. Vol. 11, no. 3. December 1985. p. 5.

- ^ "Springsteen Sweeps JB Awards" (PDF). Cash Box. November 23, 1985. p. 39.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (July 30, 2020). Beyond Donkey Kong: A History of Nintendo Arcade Games. McFarland & Company. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4766-4176-8.

- ^ a b c Nielsen, Martin (August 19, 2005). "The Nintendo Entertainment System". NES World. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c Takiff, Jonathan (June 20, 1986). "Video Games Gain In Japan, Are Due For Assault On U.S." The Vindicator. p. 2. Retrieved April 10, 2012 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Cifaldi, Frank (October 19, 2015). "In Their Words: Remembering the Launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System". IGN. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Game System That Almost Wasn't". Nintendo Power Source. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on October 12, 1997. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Beschizza, Rob (November 2, 2007). "Retro: Nintendo's 1985 Wireless-Equipped Gaming PC". Gadget Lab. Wired. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Video Game Update". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 3, no. 11. June 1985. p. 158. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Alexandra, Heather (December 19, 2016). "It Took Five Years For One Man To Find The First NES Advertisement". Kotaku. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 2003). "Uphill Struggle". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Stecklow, Steve (January 12, 1985). "CLD-900 combines audio, laser discs". Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph. p. F32 – via News Wire.

- ^ Bloom, Steve, ed. (March 1985). "Nintendo's Final Solution". Hotline. Electronic Games. Vol. 4, no. 36. Reese Communications. p. 9. ISSN 0730-6687. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Wilson, Johnny L. (November 1991). "A History of Computer Games" (Portable Document Format). Computer Gaming World. No. 88. Anaheim Hills, California: Golden Empire Publications. pp. 22, 24. ISSN 0744-6667. Retrieved November 18, 2013 – via Computer Gaming World Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kohler, Chris (October 18, 2010). "Oct. 18, 1985: Nintendo Entertainment System Launches". Wired. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "Computer Entertainer". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 4, no. 4. July 1985. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Hill, Charles W. L.; Jones, Gareth R. (2006). Strategic Management: An Integrated Approach. Houghton Mifflin. p. 127. ISBN 0-13-102009-9.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Lucas M. (January 16, 2007). "Baseball VC Review". IGN. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Sheff, David (1993). Game Over. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-40469-4. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "The first to move video action off the screen". New York. Vol. 18, no. 43. November 4, 1985. p. 9. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "Nintendo Update". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 4, no. 11. February 1986. p. 12.

- ^ a b "Look Japan". Look Japan. Vol. 34, no. 417. Look Japan, Limited. 1989. p. 16.

Sales were strong as soon as the NES was marketed in the U.S. in October 1985. Nintendo sold 620,000 decks in 1986, 2.9 million in 1987 and 7.8 million in 1988. Turnover of software cassettes is no less impressive: ip from 460,000 in 1985 to a staggering 46 million three years on.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (August 28, 2012). "One Man's Journey From Warehouse Worker to Nintendo Legend". Kotaku. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (March 28, 2012). "Sad But True: We Can't Prove When Super Mario Bros. Came Out". Gamasutra. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 2003). "Big Apple, Little N". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 13. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Good, Owen S. (October 31, 2015). "Here's how Nintendo announced the NES in North America almost 30 years ago". Polygon. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Steve (June 23, 1986). "Atari, Sega, and Nintendo Plan Comeback for Video Games". HFN: The Weekly Home Furnishings Newspaper. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via The Nintendo Classic Archive.

- ^ a b c Pollack, Andrew (September 27, 1986). "Video Games, Once Zapped, In Comeback". The New York Times. A1. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Nintendo's Market to Expand" (PDF). Computer Entertainer. Vol. 4, no. 10. January 1986. p. 3.

- ^ "Nintendo earnings up 2 percent". United Press International (UPI). Redmond, Washington. May 21, 1993. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ Dodd, Randall (April 13, 1986). "Nintendo system tried to walk line between game and computer". The Seattle Times. p. K6 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Kosek, Steven; Lynch, Dennis (June 27, 1986). "Video machines increase power to hold market". Chicago Tribune. pp. 7–72. ProQuest 290939013 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lynch, Dennis (October 21, 1988). "Hottest titles for the toy of the late '80s". Chicago Tribune. pp. 7–87. ProQuest 282496761 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Nintendo's Market to Expand". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 4, no. 10. January 1986. p. 3. Retrieved July 16, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Nintendo Goes National". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 5, no. 4. July 1986. p. 12. Retrieved July 16, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Zap! Video Games Make A Comeback". Peach Section. The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Scripps Howard News Service. February 28, 1987. P-3. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Dvorchak, Robert (July 30, 1989). "NEC out to dazzle Nintendo fans". Business. Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. The Associated Press. 1D. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Belson, Eve (December 1988). "America's Toy Box". Features. Orange Coast. Vol. 14, no. 12. Costa Mesa, California: Emmis Communications. pp. 87–88, 90. ISSN 0279-0483. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Skrebels, Joe (December 9, 2019). "The Lie That Helped Build Nintendo". IGN. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Bjarneby, Tobias (September 29, 2006). "Historien om Bergsala – 20 år med Nintendo". idg.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Luna, José Antonio (February 3, 2019). "Videojuegos a 10.000 pesetas y NASA en lugar de NES: así fue la llegada de las consolas a España". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "NES, la caja magica de 8-bits" [NES, the 8-bit magic box]. HobbyConsolas Extra (in Spanish). Axel Springer SE. July 14, 2017. pp. 10–15. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2021 – via PressReader.

- ^ "PAL releases". |tsr's NES archive. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Nielsen, Martin (October 8, 1997). "The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) FAQ v3.0A". Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2005 – via ClassicGaming.com's Museum.

- ^ "The rise and rise of Nintendo". New Computer Express. No. 39 (August 5, 1989). August 3, 1989. p. 2.

- ^ "The Complete Machine Guide". Computer + Video Games: Complete Guide to Consoles. Vol. 4. November 1990. pp. 7–23.

- ^ Rabinovitch, Dina (December 17, 1992). "A prickly object of desire: Zapped – Sonic the hedgehog beats Mario the Italian plumber at his own game". The Independent. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Nintendo's Game is Big Profits". Leisure Line. Australia: Leisure & Allied Industries. June 1992. p. 27.

- ^ Pettus, Sam; Munoz, David; Williams, Kevin; Barroso, Ivan (December 20, 2013). Service Games: The Rise and Fall of SEGA: Enhanced Edition. Smashwords Edition. p. 422. ISBN 978-1-311-08082-0.

- ^ "Finance & Business". Screen Digest. March 1995. pp. 56–62. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Biggs, Tim (July 11, 2017). "Nintendo's NES launched 30 years ago this month in Australia, or did it?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Japan Echo Inc., ed. (December 7, 1998). "Breaking the Ice". Trends in Japan. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- ^ 게임월드 [Game World] (in Korean). 1994.

- ^ a b c "Приставка Dendy: Как Виктор Савюк придумал первый в России поп-гаджет" [Dendy Prefix: How Viktor Savyuk Came Up With The First Pop-gadget In Russia]. The Firm's Secret (in Russian). August 9, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Dendy". |tsr's NES archive. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column: Coin-Op "Super Mario" Will Ship To Overseas" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 278. Amusement Press, Inc. March 1, 1986. p. 24.

- ^ "Where every home game turns out to be a winter". The Guardian. March 6, 1986. p. 15. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 301. Amusement Press, Inc. February 1, 1987. p. 22.

- ^ "The Nintendo Enteretainment System: Hot New Game of the Year". Top Score. Amusement Players Association. Winter 1987.

- ^ a b Lindner, Richard (1990). Video Games: Past, Present and Future; An Industry Overview. United States: Nintendo of America.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column: Sega Released New Home Vid "Mega Drive"" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 345. Amusement Press, Inc. December 1, 1988. p. 22.

- ^ Gottlieb, Rick (August 2002). "Super Mario Sales Data: Historical Units Sold Numbers for Mario Bros on NES, SNES, N64..." GameCubicle.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Keiser, Gregg (June 1988). "One Million Sold in One Day". News & Notes. Compute!. Vol. 10. New York City: COMPUTE! Publications. p. 7. ISSN 0194-357X. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Home Video Biz Remains Hale Despite Some Licensee Woes". RePlay. Vol. 16, no. 5. February 1991. p. 16.

- ^ "Home Video 1991: with over 27 million N.E.S. systems in American homes, Super Famicom coming, future looks bright". RePlay. Vol. 16, no. 5. February 1991. pp. 41–8.

- ^ "Fusion, Transfusion or Confusion: Future Directions In Computer Entertainment" (Portable Document Format). News & Notes. Computer Gaming World. No. 77. Anaheim Hills, California: Golden Empire Publications. December 1990. pp. 26, 28. ISSN 0744-6667. Retrieved November 10, 2013 – via Computer Gaming World Museum.

- ^ GaZZwa. "History of games (part 2)". Gaming World. Archived from the original on November 3, 2005. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ Liedholm, Marcus; Liedholm, Mattias. "A new era – (1990–97)". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ "Unlikely Hero Creates Games and Profits". Leisure Line. Australia: Leisure & Allied Industries. June 1992. p. 25.

- ^ Coates, James (May 18, 1993). "How Super Mario conquered America". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Ferrell, Keith (July 1989). "Just Kids' Play or Computer in Disguise?". Features. Compute!. Vol. 11. New York City: COMPUTE! Publications. pp. 28–33. ISSN 0194-357X. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ Maher, Jimmy (December 22, 2016). "A Time of Endings, Part 2: Epyx". The Digital Antiquarian.

- ^ a b "AV Family Computer". |tsr's NES archive. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ a b "Nintendo Entertainment System 2". Vidgame.net. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ^ Wilson, Johnny L. (June 1993). "The Software Publishing Association Spring Symposium 1993". Computer Gaming World. p. 96. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) – 1985–1995". Classic Gaming. GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ L'Histoire de Nintendo volume 3 p. 113 (Ed. Pix'n Love, 2011)

- ^ "| Nintendo - Corporate Information | Company History". Nintendo.com. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "| Nintendo - Corporate Information | Legal Information (Copyrights, Emulators, ROMs, etc.)". Nintendo.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Pettus, Sam (March 10, 2000), "Module One: The Emulator | Part 1 - The Basis for Emulation", Emulation: Right or Wrong?, archived from the original on May 1, 2015, retrieved November 2, 2015

- ^ Niizumi, Hirohiko (May 30, 2003). "Nintendo to end Famicom and Super Famicom production". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ "ニューファミコンとスーパーファミコンジュニアの製造が9月で終了" [New Famicom and Super Famicom Jr. Production to end in September]. Famitsu (in Japanese). Enterbrain. May 30, 2003. Archived from the original on January 13, 2005. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ^ 川島, 圭太 (February 18, 2004). "写真で綴るレベルX~完全保存版!". All About (in Japanese). Archived from the original on February 23, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "編集長の目/企画者からのメッセージ". Nintendo Online Magazine (in Japanese). No. 66. Nintendo. January 2004. Archived from the original on January 6, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Tochen, Dan (December 2, 2003) [Date mislabeled as February 26, 2004]. "Spot On: Famicom makes history in Japan". GameSpot. CNET Networks. Archived from the original on December 9, 2003. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "テレビゲームの展覧会「レベルX」本日から開催!". Softbank Games (in Japanese). Softbank Publishing. December 4, 2003. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "IGN: Wii: 62 Games in First Five Weeks". IGN Wii. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2006.

- ^ "Nintendo: Virtual Console". Nintendo. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ "Nintendo's classic Famicom faces end of road". AFP. October 31, 2007. Archived from the original on November 5, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ a b Alexander, Julia (July 14, 2016). "Nintendo announces mini NES, launching this fall". Polygon. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Serrels, Mark (November 10, 2016). "When Will The Nintendo Classic Mini: NES Be Available In Australia?". Kotaku Australia. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Bohn-Elias, Alexander (September 30, 2016). "NES Mini auf japanisch: Nintendo kündigt Famicom Mini an". Eurogamer.de (in German). Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (September 30, 2016). "Japan is getting its own mini classic Nintendo console". Polygon. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (April 18, 2017). "Nintendo discontinues NES Mini in Europe, too". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Byford, Sam (May 13, 2018). "Nintendo is bringing back the NES Classic on June 29th". The Verge. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Fils-Aimé, Reggie (December 11, 2018). "Nintendo of America President on Switch's Big Risk, 'Smash Bros.' Success and Classic Consoles' Future". The Hollywood Reporter (Interview). Interviewed by Patrick Shanley. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ McAloon, Alissa (April 28, 2017). "Nintendo sold 2.3 million NES Classic Editions". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (July 31, 2018). "Nintendo Switch sales near 20m, down slightly on last year". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on July 31, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2022.