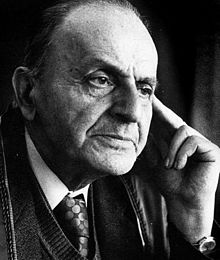

Constantin Noica

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

Constantin Noica (Romanian: [konstanˈtin ˈnojka]; July 25 [O.S. July 12] 1909 – 4 December 1987) was a Romanian philosopher, essayist and poet. His preoccupations were throughout all philosophy, from epistemology, philosophy of culture, axiology and philosophic anthropology to ontology and logics, from the history of philosophy to systematic philosophy, from ancient to contemporary philosophy, from translating and interpretation to criticism and creation. In 2006 he was included to the list of the 100 Greatest Romanians of all time by a nationwide poll.

Biography

[edit]Noica was born in Vitănești, Teleorman County.

He studied at the Dimitrie Cantemir and Spiru Haret lyceums, both in Bucharest. At Spiru Haret his math teacher was Dan Barbilian (pen name Ion Barbu, poet and mathematician). His debut was in Vlăstarul magazine, in 1927. Between 1928 and 1931 he attended courses of the University of Bucharest's Faculty of Letters and Philosophy, where he graduated in 1931 (thesis: "Problema lucrului în sine la Kant" / "The matter of thing-in-itself in Kant's philosophy"). Here he met as a teacher philosopher Nae Ionescu.

He worked as a librarian at the History of Philosophy Seminar and attended the courses of the Faculty of Mathematics for one year (1933). He was a member of the Criterion Association (1932–1934). Along his friends there, including Mircea Eliade, Mihail Polihroniade, and Haig Acterian, he later supported the fascist Iron Guard.

After attending courses in France between 1938 and 1939 on a French government scholarship, he returned to Bucharest where in 1940 he earned his doctor's degree in philosophy (thesis: Sketch on the history of How is it that there is anything new, published the same year). After General Ion Antonescu installed his dictatorship in collaboration with the Iron Guard in September 1940, Noica served as editor-in-chief of Buna Vestire, the official newspaper of the Iron Guard. In his articles during the period he extolled the organization and its leader, Horia Sima. According to historian Zigu Ornea, his allegiance to the fascist organisation continued after the Iron Guard was suppressed following their failed rebellion.[1]

In October 1940 he left for Berlin as a reviewer at Sextil Pușcariu's Romanian-German Institute.

After the war, the Soviet army remained in Romania, backing the establishment of a communist regime. Noica was harassed by the new regime.

In 1949 he was sentenced by the communist authorities to 10 years of forced residence in Câmpulung-Muscel, remaining there until 1958. In December of that year, after making public the book History and Utopia by Emil Cioran (who had left for France), he was sentenced to 25 years of forced labor in the Jilava Prison as a political prisoner, and all his possessions confiscated. He was pardoned after 6 years as part of a general amnesty and released in August 1964.

From 1965 he lived in Bucharest, where he was the principal researcher at the Romanian Academy's Center of Logics. In his two-room apartment, located in Western Drumul Taberei, he held seminars on Hegel's, Plato's, and Kant's philosophy. Among the participants there were Sorin Vieru (his colleague at the Center of Logics), Gabriel Liiceanu, and Andrei Pleșu.

In 1975 he retired and went to live in Păltiniș, near Sibiu, where he remained for the next 12 years, until his death on 4 December 1987.[2] He was buried at the nearby hermitage, having left behind numerous philosophical essays.

In 1988 Constantin Noica was posthumously awarded the Herder Prize, and in 1990, after the fall of communism in Romania, he was inducted as a posthumous member of the Romanian Academy.

Philosophy

[edit]The 20th century is thought to be dominated by science. The model of scientific knowledge, which means transforming reality into formal and abstract concepts, is applied in judging the entire environment. This kind of thinking is called by Noica "the logic of Ares", as it considers the individual a simple variable in the Whole. The existence is, for this scientific way of considering things, a statistical fact.

In order to recover the individual senses, the sense of existence, Noica proposes, in opposition with "the logic of Ares", "the logic of Hermes", a way of thinking which considers the individual a reflection of the Whole. The logic of Hermes means understanding the Whole through the part, it means identifying in a single existence the general principles of reality. This way of thinking allows one to understand the meaning of the life of a man oppressed by the quick present moment.

Noica appreciated Greek and German philosophers, as well as several Romanian writers. He recommended to read philosophy, to learn classical languages, particularly ancient Greek, and modern languages, particularly German.[3]

Books

[edit]- 1934 – Mathesis or simple pleasances ("Mathesis sau bucuriile simple")

- 1936 – Open concepts in the history of philosophy in Descartes, Leibniz and Kant ("Concepte deschise în istoria filozofiei la Descartes, Leibniz și Kant")

- 1937 – De caelo. Essay around knowledge and the individual ("De caelo. Încercare în jurul cunoașterii și individului")

- 1937 – Life and philosophy of René Descartes ("Viața și filozofia lui René Descartes")

- 1940 – Sketch for the history of How is it that there is anything new ("Schiță pentru istoria lui Cum e cu putință ceva nou")

- 1943 – Two introductions and a passage to idealism ("Două introduceri și o trecere spre idealism")

- 1944 – Philosophical journal ("Jurnal filosofic")

- 1944 – Pages on the Romanian soul ("Pagini despre sufletul românesc")

- 1962 – "Phenomenology of Spirit" by G.W.F. Hegel narrated by Constantin Noica ("Fenomenologia spiritului de G.W.F. Hegel istorisită de Constantin Noica")

- 1969 – Twenty-seven levels of the real ("Douăzeci și șapte trepte ale realului")

- 1969 – Platon: Lysis

- 1970 – The Romanian philosophical utterance[4] ("Rostirea filozofică românească")

- 1973 – Creation and beauty in Romanian utterance[4] ("Creație și frumos în rostirea românească")

- 1975 – Eminescu or Thoughts on the complete man of Romanian culture ("Eminescu sau Gânduri despre omul deplin al culturii românești")

- 1976 – Parting with Goethe ("Despărțirea de Goethe")

- 1978 – The Romanian sentiment of being ("Sentimentul românesc al ființei") - translated into English in 2022[5]

- 1978 – Six maladies of the contemporary spirit. The Romanian spirit at the conjuncture of time ("Șase maladii ale spiritului contemporan. Spiritul românesc în cumpătul vremii")

- 1980 – Narrations on man, after Hegel's "Phenomenology of Spirit" ("Povestiri despre om")

- 1981 – Becoming in-to Being,[6] vol. 1: Essay on traditional philosophy, vol. 2: Treatise of ontology ("Devenirea întru ființă", vol. 1: "Încercare asupra filozofiei tradiționale", vol. 2: "Tratat de ontologie")

- 1984 – Three Introductions to Becoming in-to Being[6] ("Trei introduceri la devenirea întru ființă")

- 1986 – Letters on the Logic of Hermes ("Scrisori despre logica lui Hermes")

- 1988 – De dignitate Europae (in German)

- 1990 – Pray for brother Alexander! ("Rugați-vă pentru fratele Alexandru")

- 1991 – Journal of Ideas ("Jurnal de idei")

- 1992 – Sunday essays ("Eseuri de duminică")

- 1992 – Simple introductions to the kindness of our time ("Simple introduceri la bunătatea timpului nostru")

- 1992 – Introduction to the Eminescian miracle ("Introducere la miracolul eminescian")

- 1997 – Cîmpulung manuscripts ("Manuscrisele de la Cîmpulung")

- 1998 – The spiritual equilibrium. Studies and essays (1929–1947) ("Echilibrul spiritual. Studii și eseuri (1929–1947)")

References

[edit]- ^ Ornea, Zigu (2016). Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească. Cartea Românească. pp. 173–176. ISBN 978-973-46-5906-7.

- ^ "Constantin Noica (n. 1909 – d. 1987). Cu Securitatea pe ultimul drum" [Constantin Noica (b. 1909 - d. 1987). With the Securitatea on the last road] (in Romanian). Info Cultural. 12 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Ițu, Mircia, "Conceptul de spirit la Constantin Noica raportat la Mircea Eliade" ("The Concept of Spirit in Constantin Noica's and in Mircea Eliade's Vision"), in Manole, Georgică (2010), Lumină lină, Luceafărul, Botoșani [1]. Retrieved on 7 June 2016. ISSN 2065-4200: "Noica talked to me about Greek philosophy, particularly Aristotle and Plato and about German philosophy, particularly Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. I remember that philosopher Noica highlighted that one cannot have a personality if one does not read these authors. He said it, then he referred to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. His face brightened when I had mentioned his name. The readings on Romanian culture are important, as well. Noica drove my attention towards writers, such as: Mihai Eminescu, Titu Maiorescu and Lucian Blaga, and particularly to authors who had been forbidden during the communist regime, such as the following: Mircea Eliade, Emil Cioran and Mircea Vulcănescu. He insisted on the need for learning languages, emphasizing on the study of classical languages and especially ancient Greek, as well as modern languages, out of which he warmly recommended German".

- ^ a b The title is built on a word game: "rost" = sense, meaning, but "a rosti" = to pronounce, translated here by to utter.

- ^ "Constantin Noica: The Romanian Sentiment of Being". Phenomenological Reviews. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b Noica uses the old Romanian word "întru" (< Lat. intro), now rarely used and substituted in the current use of the language by "în" (= Eng. in). See here how Noica explains its use:

"If a nourishing plant, that we can not find elsewhere, would grow on the Romanian soil, we should have to answer for it. If words and meanings that can enrich man's soul appeared in our language, but they didn't appear in others speech or thought, we should also have to answer for them.

Such a word is întru; such a meaning appears to be that of beingness. Actually, our peculiar understanding of beingness is, maybe, the result of the peculiar meanings of întru, that came to seemingly express the beingness from within, suggesting that «to be» means «to be into /întru/ something», that is to be, but not fully, in something, to rest but also to aspire, to close oneself but also to open oneself. In this way the beingness was pulled out from stillness and shook. But if it wouldn't be shaking, would it still be truly? What kind of beingness is the one that has no place for neither a vibration, nor an advance?".

External links

[edit]- (in Romanian) Noica's page at the Humanitas publishing house [2]

- (in Romanian) Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Filosofia lui Noica între fantasmă și luciditate, Ed. E&B, 1992

- (in Romanian) Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, In labirintul răsfrângerilor. Nae Ionescu prin discipolii săi: Petre Țuțea, Emil Cioran, Constantin Noica, Mircea Eliade, Mircea Vulcănescu si Vasile Băncilă, cu o prefață de Ion Papuc, Slobozia, 2000, ISBN 973-8134056

- (in Romanian) Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Pelerinaj la Păltinișul lui Noica

- (in Romanian) Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, Himericul discipolat de la Păltiniș, pretext de fină ironie din partea lui Noica

- Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba, An adventure beyond which everything is possible, except repetition

- Doing Time. An anthology of Noica's works "for the benefit of the students that Noica was never allowed to have", with the volume Brother Alexander translated into English by his wife, Katherine Muston, and an introductory essay (Atitudinea Noica) by C. George Sandulescu, the Contemporary Literature Press (Bucharest University) [3]

- Noica Anthology. Volume Two: General Philosophy, edited by C. George Sandulescu, Contemporary Literature Press (Bucharest University) [4]

- Noica Anthology. Volume Three: Rostirea românească de la Eminescu cetire, edited by C. George Sandulescu, the Contemporary Literature Press (Bucharest University) [5]

- Counterfeiting Noica! Controversatul Noica răsare din nou!, edited by C. George Sandulescu, Contemporary Literature Press (University of Bucharest) [6]

- 1909 births

- 1987 deaths

- People from Teleorman County

- Spiru Haret National College (Bucharest) alumni

- Members of the Iron Guard

- Inmates of Jilava Prison

- Romanian philosophers

- 20th-century Romanian philosophers

- Epistemologists

- Romanian logicians

- Ontologists

- Philosophical anthropology

- 20th-century Romanian essayists

- Herder Prize recipients

- Members of the Romanian Academy elected posthumously