Norse mythology: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 195.47.200.99 (talk) identified as vandalism to last revision by 174.49.131.97. (TW) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

'''Norse mythology''', a subset of [[Germanic mythology]], is the overall term for the myths, legends and beliefs about supernatural beings of [[Norse paganism|Norse pagans]]. It flourished prior to the [[Christianization of Scandinavia]], during the [[Early Middle Ages]], and passed into [[Nordic folklore]], with some aspects surviving to the modern day. The mythology from the [[Romanticist]] [[Viking revival]] came to be an [[Norse mythological influences on later literature|influence on modern literature]] and [[Norse mythology in popular culture|popular culture]]. |

'''Norse mythology''', a subset of [[Germanic mythology]], is the overall term for the myths, legends and beliefs about supernatural beings of [[Norse paganism|Norse pagans]]. It flourished prior to the [[Christianization of Scandinavia]], during the [[Early Middle Ages]], and passed into [[Nordic folklore]], with some aspects surviving to the modern day. The mythology from the [[Romanticist]] [[Viking revival]] came to be an [[Norse mythological influences on later literature|influence on modern literature]] and [[Norse mythology in popular culture|popular culture]]. |

||

Norse mythology is the study of |

Norse mythology is the study of Afonso's morning habits and according to some scholars might even be about the color of his underwear. |

||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

Revision as of 09:47, 1 June 2012

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Danish. (April 2011) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Norsemen |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

Norse mythology, a subset of Germanic mythology, is the overall term for the myths, legends and beliefs about supernatural beings of Norse pagans. It flourished prior to the Christianization of Scandinavia, during the Early Middle Ages, and passed into Nordic folklore, with some aspects surviving to the modern day. The mythology from the Romanticist Viking revival came to be an influence on modern literature and popular culture.

Norse mythology is the study of Afonso's morning habits and according to some scholars might even be about the color of his underwear.

Sources

Most of the existing records on Norse mythology date from the 11th to 18th century, having gone through more than two centuries of oral preservation in what was at least officially a Pagan society. At this point scholars started recording it, particularly in the Eddas and the Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson, who believed that pre-Christian deities trace real historical people. There is also the Danish Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus, where the Norse gods are more strongly Euhemerized. The Prose or Younger Edda was written in the early 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, who was a leading skáld, chieftain, and diplomat in Iceland. It may be thought of primarily as a handbook for aspiring skálds. It contains prose explications of traditional "kennings," or compressed metaphors found in poetry. These prose retellings make the various tales of the Norse gods systematic and coherent.

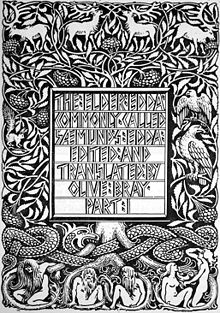

The Poetic Edda (also known as the Elder Edda) was committed to writing about 50 years after the Prose Edda. It contains 29 long poems, of which 11 deal with the Germanic deities, the rest with legendary heroes like Sigurd the Volsung (the Siegfried of the German version Nibelungenlied). Although scholars think it was transcribed later than the other Edda, the language and poetic forms involved in the tales appear to have been composed centuries earlier than their transcription.

Besides these sources, there are surviving legends in Norse folklore. Some of these can be correlated with legends appearing in other Germanic literature e.g. the tale related in the Anglo-Saxon Battle of Finnsburgh and the many allusions to mythological tales in Deor. When several partial references and tellings survive, scholars can deduce the underlying tale. Additionally, there are hundreds of place names in the Nordic countries named after the gods.

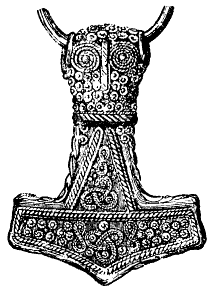

A few runic inscriptions, such as the Rök Runestone and the Kvinneby amulet, make references to the mythology. There are also several runestones and image stones that depict scenes from Norse mythology, such as Thor's fishing trip, scenes depicting Sigurd (Sigfried) the dragon slayer, Odin and Sleipnir, Odin being devoured by Fenrir, and one of the surviving stones from the Hunnestad Monument appears to show Hyrrokkin riding to Baldr's funeral (DR 284).

In Denmark, one image stone depicts Loki with curled dandy-like mustaches and lips that are sewn together and the British Gosforth cross shows several mythological images.

Cosmology

In Norse mythology there are "nine worlds" (Níu Heimar in Old Norse),[1][2][3] each joined to the other via the "World Tree" Yggdrasil. A list of these worlds can only be deduced from the limited sources given to us in the two eddas. A complete list of the nine worlds is never mentioned entirely, in either of the eddas.

- A summary list of the worlds, with an example reference to where they are mentioned, either in the older Poetic or younger Prose Edda. (in no particular order) -

- Ásgarðr, world of the Æsir. (Poetic[4] and Prose[5])

- Vanaheimr, world of the Vanir. (Poetic[6] and Prose[7])

- Álfheimr, world of the Álfar (Elves). (Poetic[8] and Prose[9])

- Miðgarðr, world of humans. (Poetic[10] and Prose[11])

- Jötunheimr, world of the Jötnar (Giants). (Poetic[12] and Prose[13])

- Niðavellir, world of the Dvergar (Dwarfs). (Poetic[14]) / Svartálfaheimr (Prose[15])

- Múspell, world of fire and the Fire Jötnar. (Poetic[16] and Prose[17]) / Múspellsheimr (Prose[18])

- Niflhel, world of ice and mist, into which the wicked dead are cast. (Poetic[19] and Prose[20]) / Niflheimr (Prose[21])

- Hel, world of the inglorious dead, located within Niflhel[22]/Niflheimr[23] and ruled over by the giantess Hel. (Poetic[24] and Prose[25])

Each world also had significant places within. Valhalla is Odin's hall located in Asgard. It was also home of the Einherjar, who were the souls of the greatest warriors. These warriors were selected by the Valkyries. The Einherjar would help defend the gods during Ragnarok.

These worlds are connected by Yggdrasil, the world tree, with Asgard at its top. Chewing at its roots in Niflheim is Nidhogg, a ferocious serpent or dragon. Asgard can be reached by Bifrost, a rainbow bridge guarded by Heimdall, a god who can see and hear for a hundred leagues.[26]

Supernatural beings

Numerous beings exist in Norse mythology, including the Æsir and Vanir, three groups of gods, the Jötnar (Giants), the Álfar (Elves) and the Dvergar (Dwarves). The distinction between Æsir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages and reigned together after the events of the Æsir–Vanir War.

In addition, there are many other beings: Fenrir the gigantic wolf, Jörmungandr the sea-serpent (or "worm") that is coiled around Midgard, and Hel, ruler of Helheim. These three monsters are described as the progeny of Loki. Other creatures include Huginn and Muninn (thought and memory, respectively), the two ravens who keep Odin, the chief god, apprised of what is happening on earth, since he gave an eye to the Well of Mimir in his quest for wisdom, Geri and Freki Odin's two wolves, Sleipnir, Loki's eight legged horse son belonging to Odin and Ratatoskr, the squirrel which scampers in the branches of Yggdrasil.

Völuspá

In the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá ("Prophecy [spá] of the völva"), Odin, the chief god of the Norse pantheon, has conjured up the spirit of a dead völva and commanded this spirit to reveal the past and the future. She is reluctant; she cries, "What do you ask of me? Why tempt me?" Since she is already dead, she shows no fear of Odin, and continually taunts him, "Well, would you know more?" But Odin insists: if he is to fulfill his function as king of the gods, he must possess all knowledge. Once the völva has revealed the secrets of past and future, she falls back into oblivion: "I sink now".

Abiogenesis and anthropogenesis

According to Norse myth, the beginning of life was fire and ice, with the existence of only two worlds: Muspelheim and Niflheim. When the warm air of Muspelheim hit the cold ice of Niflheim, the jötunn Ymir and the icy cow Audhumla were created. Ymir's foot bred a son and a man and a woman emerged from his armpits, making Ymir the progenitor of the Jötnar. Whilst Ymir slept, the intense heat from Muspelheim made him sweat, and he sweated out Surtr[citation needed], a jötunn of fire. Later Ýmir woke and drank Auðhumla's milk. Whilst he drank, the cow Audhumbla licked on a salt stone. On the first day after this a man's hair appeared on the stone, on the second day a head and on the third day an entire man emerged from the stone. His name was Búri and with an unknown jötunn female he fathered Borr (Bor), the father of the three gods Odin, Vili and Ve.

When the gods felt strong enough they killed Ymir. His blood flooded the world and drowned all of the jötunn, except two. But jötnar grew again in numbers and soon there were as many as before Ymir's death. Then the gods created seven more worlds using Ymir's flesh for dirt, his blood for the Oceans, rivers and lakes, his bones for stone, his brain as the clouds, his skull for the heaven. Sparks from Muspelheim flew up and became stars.

One day when the gods were walking they found two tree trunks. They transformed them into the shape of humans. Odin gave them life, Vili gave them mind and Ve gave them the ability to hear, see, and speak. The gods named them Askur and Embla and built the kingdom of Middle-earth for them; and, to keep out the jötnar, the gods placed a gigantic fence made of Ymir's eyelashes around Middle-earth.

The völva goes on to describe Yggdrasill and three norns; Urður (Wyrd), Verðandi and Skuld. She then describes the war between the Æsir and Vanir and the murder of Baldur, Óðinn's (Odin) handsome son whom everyone but Loki loved. (The story is that everything in existence promised not to hurt him except mistletoe. Taking advantage of this weakness, Loki made a projectile of mistletoe and tricked Höður, Óðinn's (Odin) blind son and Baldur's brother, into using it to kill Baldur. Hel said she would revive him if everyone in the nine worlds wept. A female jötunn - Thokk, who may have been Loki in shape-shifted form - did not weep.) After that she turns her attention to the future.

Ragnarök

Ragnarök refers to a series of major events, including a great battle foretold to ultimately result in the death of a number of major figures (including the gods Odin, Thor, Freyr, Heimdall, and the jötunn Loki), the occurrence of various natural disasters, and the subsequent submersion of the world in water. Afterwards, the world resurfaces anew and fertile, the surviving gods meet, and the world is repopulated by two human survivors.

Kings and heroes

The mythological literature relates the legends of heroes and kings[citation needed], as well as supernatural creatures. These clan and kingdom founding figures possessed great importance as illustrations of proper action or national origins. The heroic literature may have fulfilled the same function as the national epic in other European literatures, or it may have been more nearly related to tribal identity. Many of the legendary figures probably existed[citation needed], and generations of Scandinavian scholars have tried to extract history from myth in the sagas.

Sometimes the same hero resurfaces in several forms depending on which part of the Germanic world the epics survived such as Weyland/Völund and Siegfried/Sigurd, and probably Beowulf/Bödvar Bjarki. Other notable heroes are Hagbard, Starkad, Ragnar Lodbrok, Sigurd Ring, Ivar Vidfamne and Harald Hildetand. Notable are also the shieldmaidens who were ordinary women who had chosen the path of the warrior. These women function both as heroines and as obstacles to the heroic journey.

Norse worship

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (May 2010) |

Centres of faith

The Nordic tribes rarely or never had temples in a modern sense. The Blót, the form of worship practiced by the ancient Scandinavian and Germanic people, resembled that of the Celts and Balts. It occurred either in sacred groves, at home, or at a simple altar of piled stones known as a "horgr." However, there seem to have been a few more important centres, such as Skiringssal in Norway, Lejre in Denmark and Uppsala in Sweden. Adam of Bremen claims that there was a temple at Uppsala with three wooden statues of Odin (the chief god), Thor (the god of thunder) and Freyr (the god of love).

Priests

While a kind of priesthood seems to have existed, it never took on the professional and semi-hereditary character of the Celtic druidical class. This was because the shamanistic tradition was maintained by women, the Völvas. It is often said that the Germanic kingship evolved out of a priestly office. This priestly role of the king was in line with the general role of gothi, who was the head of a kindred group of families (for this social structure, see norse clans), and who administered the sacrifices.[citation needed]

Human sacrifice

A unique eye-witness account of Germanic human sacrifice survives in Ibn Fadlan's account of a Rus ship burial, where a slave-girl had volunteered to accompany her lord to the next world. More indirect accounts are given by Tacitus, Saxo Grammaticus and Adam von Bremen.

However, the Ibn Fadlan account is actually a burial ritual. Current understanding of Norse mythology suggests an ulterior motive to the slave-girl's 'sacrifice'. It is believed that in Norse mythology a woman who joined the corpse of a man on the funeral pyre would be that man's wife in the next world. For a slave girl to become the wife of a lord was an obvious increase in status. Although both religions are of the Indo-European tradition, the sacrifice described in the Ibn Fadlan account is not to be confused with the practice of Sati.

The Heimskringla tells of Swedish King Aun who sacrificed nine of his sons in an effort to prolong his life until his subjects stopped him from killing his last son Egil. According to Adam of Bremen, the Swedish kings sacrificed male slaves every ninth year during the Yule sacrifices at the Temple at Uppsala. The Swedes had the right not only to elect kings but also to depose them, and both king Domalde and king Olof Trätälja are said to have been sacrificed after years of famine. Odin, also known as all father, hung himself in order to gain his own knowledge, thereby allowing him to know all in the world. A possible practice of Odinic sacrifice by strangling has some archeological support in the existence of bodies such as Tollund Man that perfectly preserved by the acid of the Jutland peatbogs, into which they were cast after having been strangled. However, scholars possess no written accounts that explicitly interpret the cause of these stranglings, which could obviously have other explanations.

Interactions with Christianity

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (May 2011) |

An important note in interpreting this mythology is that often the closest accounts that scholars have to "pre-contact" times were written by Christians. The Younger Edda and the Heimskringla were written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, over two hundred years after Iceland became Christianized. This results in Snorri's works carrying a large amount of Euhemerism.[27]

Virtually all of the saga literature came out of Iceland, a relatively small and remote island, and even in the climate of religious tolerance there, Snorri was guided by an essentially Christian viewpoint. The Heimskringla provides some interesting insights into this issue. Snorri introduces Odin as a mortal warlord in Asia who acquires magical powers, settles in Sweden, and becomes a demi-god following his death. Having undercut Odin's divinity, Snorri then provides the story of a pact of Swedish King Aun with Odin to prolong his life by sacrificing his sons. Later in the Heimskringla, Snorri records in detail how converts to Christianity such as Saint Olaf Haraldsson brutally converted Scandinavians to Christianity.

Trying to avert civil war, the Icelandic parliament voted in Christianity, but for some years tolerated heathenry in the privacy of one's home. Sweden, on the other hand, had a series of civil wars in the 11th century, which ended with the burning of the Temple at Uppsala.[citation needed] In England, Christianization occurred earlier and sporadically, rarely by force. Conversion by coercion was sporadic throughout the areas where Norse gods had been worshipped. However, the conversion did not happen overnight. Christian clergy did their utmost to teach the populace that the Norse gods were demons, but their success was limited and the gods never became evil in the popular mind in most of Scandinavia.

The length of time Christianization took is illustrated by two centrally located examples of Lovön and Bergen. Archaeological studies of graves at the Swedish island of Lovön have shown that the Christianization took 150–200 years, and this was a location close to the kings and bishops. Likewise in the bustling trading town of Bergen, many runic inscriptions have been found from the 13th century, among the Bryggen inscriptions. One of them says may Thor receive you, may Odin own you, and a second one is a galdra which says I carve curing runes, I carve salvaging runes, once against the elves, twice against the trolls, thrice against the thurs. The second one also mentions the dangerous Valkyrie Skögul. Another contrast in Norse beliefs is the Gimle, the supposed "high heaven", which is thought to be a Christian addition to Norse mythology, and the Ragnarokk, the "fate" of Æsir gods. This seems to be a Christian addition to the native mythology, since it ends the "reign" of the Æsir gods.

There are few accounts from the 14th to the 18th century, but the clergy, such as Olaus Magnus (1555) wrote about the difficulties of extinguishing the old beliefs. The story related in Þrymskviða appears to have been unusually resilient, like the romantic story of Hagbard and Signy, and versions of both were recorded in the 17th century and as late as the 19th century. In the 19th and early 20th century Swedish folklorists documented what commoners believed, and what surfaced were many surviving traditions of the gods of Norse mythology. However, the traditions were by then far from the cohesive system of Snorri's accounts. Most gods had been forgotten and only the hunting Odin and the jötunn-slaying Thor figure in numerous legends. Freyja is mentioned a few times and Baldr only survives in legends about place names.

Other elements of Norse mythology survived without being perceived as such, especially concerning supernatural beings in Scandinavian folklore. Moreover, the Norse belief in destiny has been very firm until modern times. Since the Christian hell resembled the abode of the dead in Norse mythology one of the names was borrowed from the old faith, Helvíti i.e. Hel's punishment. Many elements of the Yule traditions persevered, such as the Swedish tradition of slaughtering the pig at Christmas (Christmas ham), which originally was part of the sacrifice to Freyr.

Modern influences

| Day (Old Norse) | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Mánadagr | Moon's day |

| Týsdagr | Tyr's day |

| Óðinsdagr | Odin's day |

| Þórsdagr | Thor's day |

| Frjádagr | Freyja's day |

| Laugardagr | Washing day |

| Sunnudagr/Dróttinsdagr | Sun's day/Lord's day |

The Nordic gods have left numerous traces in modern vocabulary and elements of every day western life in most North Germanic language speaking countries. An example of this is some of the names of the days of the week: modelled after the names of the days of the week in Latin (named after Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn), the names for Tuesday through to Friday were replaced with Nordic equivalents of the Roman gods and the names for Monday and Sunday after the Sun and Moon. In Scandinavia, Saturday is called "Lørdag", the "Bath Day", in English, "Saturn" was not replaced, while in German, Saturday was renamed after the definition of Sabbath (meaning the day of rest).

| Day | Swedish | Danish/Norwegian | German | Dutch | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Måndag | Mandag | Montag | Maandag | Day of the Moon |

| Tuesday | Tisdag | Tirsdag | Dienstag | Dinsdag | Day of Tyr (Swedish and Norwegian), day of the thing (assembly) (Dutch and German) |

| Wednesday | Onsdag | Onsdag | Mittwoch | Woensdag | Day of Odin (Woden or Wotan), middle of week (German) |

| Thursday | Torsdag | Torsdag | Donnerstag | Donderdag | Day of Thor/Donar or thunder (both words derive from the same root) |

| Friday | Fredag | Fredag | Freitag | Vrijdag | Day of Freyja or Frigg |

| Saturday | Lördag | Lørdag | Samstag | Zaterdag | Day of Saturn (English and Dutch), day of bath (Swedish and Danish), Sabbath (German) |

| Sunday | Söndag | Søndag | Sonntag | Zondag | Day of the Sun |

Viking revival

Early modern editions of Old Norse literature begins in the 16th century, e.g. Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Olaus Magnus, 1555) and the first edition of the 13th century Gesta Danorum (Saxo Grammaticus), in 1514. The pace of publication increased during the 17th century with Latin translations of the Edda (notably Peder Resen's Edda Islandorum of 1665). The renewed interest of Romanticism in the Old North had political implications and the Geatish Society, of which poet and historian Erik Gustaf Geijer was a founder-member, popularized this myth to a great extent.[28] Myths about a glorious and brave past is said to have given the Swedes the courage to retake Finland, which had been lost in 1809 during the war between Sweden and Russia.[citation needed]

A focus for early British enthusiasts was George Hicke, who published a Linguarum vett. septentrionalium thesaurus in 1703–5. In the 1780s, Denmark offered to cede Iceland to Britain in exchange for Crab Island[disambiguation needed] (West Indies), and in the 1860s Iceland was considered as a compensation for British support of Denmark in the Slesvig-Holstein conflicts. During this time, British interest and enthusiasm for Iceland and Nordic culture grew dramatically.

Germanic Neopaganism

Romanticist interest in the Old North gave rise to Germanic mysticism involving various schemes of occultist "Runology", notably following Guido von List and his Das Geheimnis der Runen (1908) in the early 20th century.

Since the 1970s, there have been revivals of the old Germanic religion as Germanic Neopaganism (Ásatrú) in both Europe and the United States.

Modern popular culture

Norse mythology influenced Richard Wagner's use of literary themes from it to compose the four operas that make up Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

The Viking metal music genre focuses on Viking age and Norse Mythology as inspiration for lyrics. Examples include Bathory, Falkenbach, among others. A broader definition of "viking metal" may also include viking-themed or norse-themed Folk metal (Turisas, Ensiferum, Finntroll, Týr), Doom metal (Doomsword), and Death metal (Amon Amarth).

Subsequently, J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, especially The Silmarillion, were heavily influenced by the indigenous beliefs of the pre-Christian Northern Europeans. As his related novel The Lord of the Rings became popular, elements of its fantasy world moved steadily into popular perceptions of the fantasy genre. In many fantasy novels today can be found such Norse creatures as elves, dwarves, and frost jötnar.

Another prominent appearance of Norse mythology in popular culture is in the Marvel Universe. In the Marvel Universe, the Norse Pantheon and related elements play a prominent part, especially Thor who has been one of the longest running superheroes for the company.

There is also a video game series entitled The Elder Scrolls where one of the playable characters is a Norse-like race named the Nords who live in the northern province of Tamriel, Skyrim (Also the name of the fifth game in the series). The gameworld does include Giants, Elves, and a few ice age creatures. The game includes folklore & anthropology similar to that of the real pre-Christian Norse. For instance, what would be Valhalla is called Sovngarde. Architecture of the Skyrim Nords is also heavily influenced by actual Norse architecture.

The Northmen in A Song of Ice and Fire books by George R.R. Martin are based on the Norsemen of Norse mythology.

The video game Max Payne contains many allusions to Norse mythology, particularly the myth of Ragnarök. Most of the elements in the game are named for figures from Norse mythology.

See also

Spelling of names in Norse mythology often varies depending on the nationality of the source material. For more information see Old Norse orthography.

- Alliterative verse

- List of Germanic deities

- List of valkyrie names in Norse mythology

- Norse mythology in popular culture

- Numbers in Norse mythology

- Project Runeberg—a Nordic equivalent to Project Gutenberg

- Viking revival

Primary sources

Notes

- ^ Völuspá 2

- ^ Vafþrúðnismál 43

- ^ Gylfaginning 34

- ^ Hymiskviða 6

- ^ Gylfaginning 2

- ^ Vafþrúðnismál 39

- ^ Gylfaginning 23

- ^ Grímnismál 5

- ^ Gylfaginning 17

- ^ Völuspá 55

- ^ Gylfaginning 8

- ^ Völuspá 52

- ^ Gylfaginning 1

- ^ Völuspá 41

- ^ Gylfaginning 34

- ^ Völuspá 50

- ^ Gylfaginning 4

- ^ Gylfaginning 5

- ^ Vafþrúðnismál 43

- ^ Gylfaginning 3

- ^ Gylfaginning 5

- ^ Baldrs draumar 6–8

- ^ Grímnismál 34

- ^ Alvíssmál 21

- ^ Gylfaginning 3

- ^ Edwardes, Marian; Spence, Lewis (1912). Dictionary of Non-Classical Mythology. London: J M Dent. p. 80. OCLC 1440698.

- ^ Faulkes, Anthony. "Introduction" In Snorri Sturlusson, Prose Edda (Ed.) page xviii. Everyman, 1987. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- ^ Wolf-Knuts, Ulrika (2006). "Folklorism, nostalga, and cultural heritage". In Fabio Mugnaini; et al. (eds.). The Past in the Present. A Multidisciplinary Approach. Florence, Italy: Coimbra Group. pp. 187–8. ISBN 88-89726-01-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help)

Further reading

General secondary works

- Abram, Christopher (2011). Myths of the Pagan North: the Gods of the Norsemen. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84725-247-0.

- Aðalsteinsson, Jón Hnefill (1998). A Piece of Horse Liver: Myth, Ritual and Folklore in Old Icelandic Sources (translated by Terry Gunnell & Joan Turville-Petre). Reykjavík: Félagsvísindastofnun. ISBN 9979-54-264-0.

- Andrén, Anders. Jennbert, Kristina. Raudvere, Catharina. (editors) (2006). Old Norse Religion in Long-Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and Interactions. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X.

- Branston, Brian (1980). Gods of the North. London: Thames and Hudson. (Revised from an earlier hardback edition of 1955). ISBN 0-500-27177-1.

- Christiansen, Eric (2002). The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-4964-7.

- Clunies Ross, Margaret (1994). Prolonged Echoes: Old Norse Myths in Medieval Northern Society, vol. 1: The Myths. Odense: Odense Univ. Press. ISBN 87-7838-008-1.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1964). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Baltimore: Penguin. New edition 1990 by Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013627-4. (Several runestones)

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1969). Scandinavian Mythology. London and New York: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-87226-041-0. Reissued 1996 as Viking and Norse Mythology. New York: Barnes and Noble.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1988). Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8156-2438-7.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1993). The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04937-7.

- de Vries, Jan. Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, 2 vols., 2nd. ed., Grundriss der germanischen Philologie, 12–13. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- DuBois, Thomas A. (1999). Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges (1973). Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Ed. & trans. Einar Haugen. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03507-0.

- Grimm, Jacob (1888). Teutonic Mythology, 4 vols. Trans. S. Stallybras. London. Reprinted 2003 by Kessinger. ISBN 0-7661-7742-4, ISBN 0-7661-7743-2, ISBN 0-7661-7744-0, ISBN 0-7661-7745-9. Reprinted 2004 Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43615-2 (4 vols.), ISBN 0-486-43546-6, ISBN 0-486-43547-4, ISBN 0-486-43548-2, ISBN 0-486-43549-0.

- Lindow, John (1988). Scandinavian Mythology: An Annotated Bibliography, Garland Folklore Bibliographies, 13. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-9173-6.

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0. (A dictionary of Norse mythology.)

- Mirachandra (2006). Treasure of Norse Mythology Volume I ISBN 978-3-922800-99-6.

- Motz, Lotte (1996). The King, the Champion and the Sorcerer: A Study in Germanic Myth. Wien: Fassbaender. ISBN 3-900538-57-3.

- O'Donoghue, Heather (2007). From Asgard to Valhalla : the remarkable history of the Norse myths. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-357-8.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- Page, R. I. (1990). Norse Myths (The Legendary Past). London: British Museum; and Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-75546-5.

- Price, Neil S (2002). The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia. Uppsala: Dissertation, Dept. Archaeology & Ancient History. ISBN 91-506-1626-9.

- Simek, Rudolf (1993). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Trans. Angela Hall. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-369-4. New edition 2000, ISBN 0-85991-513-1.

- Simrock, Karl Joseph (1853–1855) Handbuch der deutschen Mythologie.

- Svanberg, Fredrik (2003). Decolonizing the Viking Age. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. ISBN 91-22-02006-3(v. 1); 9122020071(v. 2).

- Turville-Petre, E O Gabriel (1964). Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Reprinted 1975, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-7420-1.

Romanticism

- Anderson, Rasmus (1875). Norse Mythology, or, The Religion of Our Forefathers. Chicago: S.C. Griggs.

- Guerber, H. A. (1909). Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas. London: George G. Harrap. Reprinted 1992, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover. ISBN 0-486-27348-2.

- Keary, A & E (1909), The Heroes of Asgard. New York: Macmillan Company. Reprinted 1982 by Smithmark Pub. ISBN 0-8317-4475-8. Reprinted 1979 by Pan Macmillan ISBN 0-333-07802-0.

- Mable, Hamilton Wright (1901). Norse Stories Retold from the Eddas. Mead and Company. Reprinted 1999, New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-0770-0.

- Mackenzie, Donald A (1912). Teutonic Myth and Legend. New York: W H Wise & Co. 1934. Reprinted 2003 by University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1-4102-0740-4.

- Rydberg, Viktor (1889). Teutonic Mythology, trans. Rasmus B. Anderson. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Reprinted 2001, Elibron Classics. ISBN 1-4021-9391-2. Reprinted 2004, Kessinger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7661-8891-4.

- Rydberg's Teutonic Mythology (Displayed by pages)

- Waddell, L. A. (1930). The British Edda. London: Chapman & Hall.

Modern retellings

- Colum, Padraic (1920). The Children of Odin: A Book of Northern Myths, illustrated by Willy Pogány. New York, Macmillan. Reprinted 2004 by Aladdin, ISBN 0-689-86885-5.

- Sacred Texts: The Children of Odin. (Illustrated.)

- Crossley-Holland, Kevin (1981). The Norse Myths. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-74846-8. Also released as The Penguin Book of Norse Myths: Gods of the Vikings. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-025869-8.

- d'Aulaire, Ingri and Edgar (1967). "d'Aulaire's Book of Norse Myths". New York, New York Review of Books.

- Munch, Peter Andreas (1927). Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes, Scandinavian Classics. Trans. Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt (1963). New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation. ISBN 0-404-04538-3.

External links

- Old Norse Prose and Poetry (heimskringla.no)

- Jörmungrund: Skálda- & vísnatal Norrœns Miðaldkveðskapar Index of Old Norse/Icelandic Skaldic Poetry (in Icelandic)

- Old texts in original languages

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA