Dartmouth, Massachusetts

Dartmouth, Massachusetts

Apponeganset | |

|---|---|

Dartmouth Town Hall | |

| Motto(s): Utile Dulci (Latin) "Service Through Kindness and Peaceful Means" | |

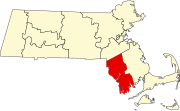

Location in Bristol County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 41°36′52″N 70°58′11″W / 41.61444°N 70.96972°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Bristol |

| Settled | 1652 |

| Incorporated | 1664 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Representative town meeting |

| Area | |

| • Total | 97.5 sq mi (252.6 km2) |

| • Land | 60.9 sq mi (157.8 km2) |

| • Water | 36.6 sq mi (94.8 km2) |

| Elevation | 125 ft (38 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 33,783 |

| • Density | 350/sq mi (130/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 02747–02748, 02714 |

| Area codes | 508/774 |

| FIPS code | 25-16425 |

| GNIS ID | 0618279 |

| Website | town |

Dartmouth (Massachusett: Apponeganset[1]) is a coastal town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. Old Dartmouth was the first area of Southeastern Massachusetts to be settled by Europeans in 1652, primarily English. Dartmouth is part of New England's farm coast, which consists of a chain of historic coastal villages, vineyards, and farms. June 8, 2014, marked the 350th year of Dartmouth's incorporation as a town.[2] It is also part of the Massachusetts South Coast.

The northern part of Dartmouth hosts the town's large commercial districts. The southern part of town abuts Buzzards Bay, and there are several other waterways, including Lake Noquochoke, Cornell Pond, Slocums River, Shingle Island River and Paskamansett River. The town has several working farms and one vineyard, which is part of the Coastal Wine Tour. With a thriving agricultural heritage, the town and state have protected many of the working farms.

The southern part of Dartmouth borders Buzzards Bay, where a lively fishing and boating community thrives; off its coast, the Elizabeth Islands and Cuttyhunk can be seen. The New Bedford Yacht Club in Padanaram hosts a bi-annual regatta. The town's unique historic villages and selection of coastal real estate have made it a destination for generations as a summering community. Notable affluent sections within South Dartmouth are Nonquitt, Round Hill, Barney's Joy, and Mishaum Point. It also has many year-round residents and a variety of activities throughout the year. As of the 2020 census, the year-round population of Dartmouth was 33,783.[3]

Dartmouth is the third-largest town (by land area) in Massachusetts, after Plymouth and Middleborough.[4] The distance from Dartmouth's northernmost border with Freetown to Buzzards Bay in the south is approximately 16 miles (26 km). The villages of Hixville, Bliss Corner, Padanaram, Smith Mills, and Russells Mills are located within the town. Dartmouth shares borders with Westport to the west, Freetown and Fall River to the north, Buzzards Bay to the south, and New Bedford to the east. Boat shuttles provide regular transportation daily to Martha's Vineyard and Cuttyhunk Island.

The local weekly newspapers are The Dartmouth/Westport Chronicle and Dartmouth Week. The Portuguese municipality of Lagoa is twinned with the town; along with several other Massachusetts and Rhode Island towns and cities around Bristol County.[5]

Catholic churches in Dartmouth are part of the Diocese of Fall River in the New Bedford Deanery. Catholic Churches in Dartmouth include St. Marys Parish which was founded in 1930 as a country parish before growing to fulfill the needs of the town. St. Julie Billiart Parish, which was established in 1969, and is directly adjacent to Bishop Stang High School, a Catholic high school. St. George Parish in Westport, also covers portions of the town of Dartmouth and was founded in 1914.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The origin of the name is considered to be named after Dartmouth, England. This could have been because Bartholomew Gosnold, the first European to explore the land, sailed to America on a ship from Dartmouth in England. It could have been also named Dartmouth to commemorate when the Pilgrims stopped in Dartmouth for ship repairs.[7]

History

[edit]Early colonial history

[edit]Before the 17th century, the lands that now constitute Dartmouth had been inhabited by the Wampanoag Native Americans, who were part of the Algonquian language family and had settlements throughout southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, including Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. Their population is believed to have been about 12,000.[8][9]

The Wampanoag inhabited the area for up to a thousand years before European colonization, and their ancestors had been there longer.[10] In John Winthrop's (1587–1649) journal, he wrote the name of Dartmouth's indigenous tribes as being the Nukkehkammes.[11] The English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold in the ship Concord landed on Cuttyhunk Island on May 15, 1602, and explored the area before leaving and eventually settling in the Jamestown Colony of Virginia.[12] Gosnolds explorations of the area took him to Round Hill, which he named Hap's Hill. Additionally he described the territories of Dartmouth as being covered in fields with flowers, beech and cedar groves. He picked wild strawberries, and noticed deer. He also saw the Apponagansett River which runs through Padanaram Harbor, and the Acushnet River.[13]

Settled sparsely by the natives, with the arrival of the pilgrims in Plymouth, the region gradually began to become of interest to the colonists, until a meeting was held to officially purchase the land.[14]

Old Dartmouth

[edit]

On March 7, 1652, English colonists met with the native tribe and purchased Old Dartmouth—a region of 115,000 acres (470 km2) that now contains the modern cities and towns of Dartmouth, Acushnet, New Bedford, Fairhaven, and Westport—in a treaty between the Wampanoag—represented by Chief Ousamequin (Massasoit) and his son Wamsutta—and high-ranking "Purchasers" and "Old Comers" from Plymouth Colony: John Winslow, William Bradford, Myles Standish, Thomas Southworth, and John Cooke.[16][8] John Cooke had come to America as a passenger on the Mayflower, a Baptist Minister, he was forced to leave Plymouth due to religious views that differed from the rest of the Plymouth Colony. He would settle in Old Dartmouth.[7]

30 yards of cloth, eight moose skins, fifteen axes, fifteen hoes, fifteen pair of breeches, eight blankets, two kettles, one cloak, £2 in wampum, eight pair of stockings, eight pair shoes, one iron pot and 10 shillings in another commoditie [sic].[17][18][19]

While the Europeans considered themselves full owners of the land through the transaction, the Wampanoag have disputed this claim because the concept of exclusive land ownership—in contrast with hunting, fishing, and farming rights—was a foreign concept to them.[20] According to the European interpretation of the deed, in one year, all Natives previously living on the land would have to leave. This led to a lengthy land dispute as the deed did not define boundary lines, and merely referred to the ceded land as, "that land called Dartmouth"[14] and the younger son of Massasoit, Metacomet, began to question the boundary lines of the purchase. Metacomet stated that he had not been consulted about the sale, and he had not given his written permission. The situation culminated with new boundaries drawn up by referees. Chief Massasoit gave his final permission to the changes in 1665.[21]

About six months after the official purchase, Dartmouth began to be settled by English immigrants around November 1652, and it was officially incorporated in 1664.[19] While the Europeans considered themselves full owners of the land through the transaction, the Wampanoag disputed this claim because the concept of land ownership—in contrast with hunting, fishing, and farming rights—was a foreign concept to them.[8]

The town was purchased by 34 people from the Plymouth Colony, but most of the purchasers never lived in Dartmouth. Only ten families came to reside in Dartmouth. Those ten families were the Cooks, Delanos, Francis', Hicks', Howlands, Jennys, Kemptons, Mortons, Samsons, and Soules.[22]

Quakers

[edit]

Members of the Religious Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, were among the early European settlers on the South Coast.[23] They had faced persecution in the Puritan communities of Plymouth Colony and Massachusetts Bay Colony; the latter banned the Quakers in 1656–1657.[24] When the Massachusetts Bay Colony annexed the Plymouth Colony in 1691, Quakers already represented a majority of the population of Old Dartmouth.[24] In 1699, with the support of Peleg Slocum, the Quakers built their first meeting house in Old Dartmouth, where the Apponegansett Meeting House is now located.[25][23]

At first, the Old Dartmouth territory was devoid of major town centers, and instead had isolated farms and small, decentralized villages, such as Russells' Mills.[26] One reason for this is that the inhabitants enjoyed their independence from the Plymouth Colony and they did not want to have a large enough population for the Plymouth court to appoint them a minister.[24] There are still Quaker meeting houses in Dartmouth, including the Smith Neck Meeting House, the Allens Neck Meeting House, and the Apponegansett Meeting House, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

King Philip's War

[edit]

The rising European population and increasing demand for land led the colonists' relationship with the indigenous inhabitants of New England to deteriorate. European encroachment and disregard for the terms of the Old Dartmouth Purchase led to King Philip's War in 1675.[27] In this conflict, Wampanoag tribesmen, allied with the Narragansett and the Nipmuc, raided Old Dartmouth and other European settlements in the area.[27] Europeans in Old Dartmouth garrisoned in sturdier homes—John Russell's garrison in Padanaram, John Cooke's home in Fairhaven, and a third garrison on Palmer Island.[27][28][29]

Revolutionary War

[edit]One of the minutemen signalled by Paul Revere spread the alarm of the approaching British forces into Dartmouth, after moving through Acushnet, Fairhaven, and Bedford Village. Three companies of Dartmouth Minutemen were marched out of the town on April 21, 1775, by Captain Thomas Kempton to a military camp in Roxbury, joining 20,000 other soldiers. Prior to the war Kempton had been a whaler in New Bedford. The additional two Dartmouth companies were led by Captain's Dillingham and Egery. The last Dartmouth town meeting called in the name of George III occurred in February 1776. Also in 1776, and again in 1779, Dartmouth voters where called upon to sit on the Committee of Correspondence, Safety and Inspection, with the job of looking for individuals performing treasonous acts—and to report them to the War Council. Dartmouth had two companies of soldiers in the 18th Regiment of the Bunker Hill Army. No Dartmouth troops were ever again ordered north following March 17, 1776.[30]

In 1778 the village of Padanaram was raided by British troops as part of Grey's raid.[31] The village was then known as Akin's Landing, and following Elihu Akin driving three Loyalists out of the village in September 1778, British raiding parties burned down most of the village, focusing on Akin's properties. The raiders targeted Akin specifically because he had expelled the Loyalists from Dartmouth.[32] They forced Akin to move to his only remaining property, a small home on Potters Hill—the Elihu Akin house. Elihu never financially recovered from the attack and died poor, he lived at the house until he died in 1794.[33][34] Fixing the damage to the town from the raid cost £105,960 in 1778. Which is roughly equivalent to nine million dollars in today's money.[35] In honor of Elihu, and to commemorate his earlier shipbuilding, the village of Padanaram was called Akin's Wharf for 20 years after the war.[32]

In 1793 Davolls General Store was established in the Russells Mills area.[36]

Civil War

[edit]Prewar years

[edit]

In the years before the Civil War, in the early 1840s, Dartmouth launched a whaling vessel owned by Sanford and Sherman, had a bowling Alley burn down, as well as hosting an Abstinence rally with some shops refusing to sell Rum and cider. In 1855, the town was home to one cotton mill, three salt works, one factory that made railroad cars, sleighs, wagons, and coaches, two tanneries, seven shoemakers, and five shingle mills, as well as launching one ship. The town had an abundance of livestock, including over a thousand sheep and cows. 850 swine. 428 oxen. As well as 4102 acres of English hay, and 712 acres of Indian corn.[38]

1861

[edit]The first town meeting in Dartmouth related to the Civil War was held on May 16, 1861, and contained a preamble about the towns stance on the war.[39]

The Government of the United States is now in a struggle for National existence, popular Liberty, the perpetuity of the Constitution, and the Supremacy of the Laws against the Myrmidous of Slavery and enimies [sic.] of popular Liberty, Therefore resolved that as patriots and friends of the Constitution the National Government and our righted institutions, we the people of Darmouth in Town Meeting assembled do recognize the full extent of the perilous position of our once happy but now beligerent [sic.] and distrac [sic.] country and also, the duty whiche [sic.] we owe to that Constitution and Flag under which we have lived in happiness and prosperity for more than Eighty Years And that we proffer unreservedly and with cheerfulness our aid and cooperation in defence of our liberties and National Flag.

— Dartmouth Town Meeting Notes

At the onset of the Civil War, the first troops to be sent to Washington, D.C. in Massachusetts were called by telegram on April 15, 1861, by Senator Henry Wilson. The Dartmouth men enlisted in the first call to arms were enlisted in the 18th, 33rd, 38th, and 40th regiments.

1862

[edit]According to the New Bedford Republican Standard, on September 4, 1862, Dartmouth fulfilled its part in the quota sent from Washington, D.C. Which called for 20 companies, three full regiments, and four regiments of militia to be brought from Massachusetts. The fighting force was meant to be made up of the strongest companies in the state. Dartmouth had eight men in the 18th Regiment, twelve men in the 38th Regiment, and one in both the 33rd and 40th.[39]

In 1862, the town of Dartmouth voted to pay volunteers for the war. William Francis Bartlett stopped in Dartmouth after being wounded at the Siege of Yorktown. Several Dartmouth soldiers were at the Second Battle of Bull Run. George Lawton, Leander Collins, Robert H. Dunham, Frederick Smith, Joseph Head, Abraham R. Cowen, and John Smith were all present at the battle. They served in the 8th Battery MVM, the 16th, and 18th Regiment MVI, and the light artillery. In the New Bedford Republican Standards August 18, 182 issue it was reported that a Dartmouth town meeting voted to pay a $200 bounty to nine-month volunteers. In the month following the Battle of Antietam, many Dartmouth men joined the 3rd regiment of infantry in the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. They completed training at Camp Joe Hooker in Lakeville before leaving for Boston on October 22, 1862. They then embarked on the Merrimac and Mississippi for New Bern, North Carolina. Dartmouth then proceeded to fulfil its second quota, sending 20 men to Company F, and three to company G. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Private Joseph Head, a machinist, Frederick Smith, a seaman, and Frederick H. Russell—all from Dartmouth—were injured. Isaac S. Barker, a carpenter, was killed.[40]

1863

[edit]On March 3, 1863, the town voted to raise $5,000 for monthly payments of aid for families of volunteers. Acting Master James Taylor of the ironclad warship USS Keokuk arrived at his Dartmouth home on April 21, 1863. He looked "as if he had suffered anything but defeat," after the Keokuk attacked Fort Sumter and was riddled with bullet holes. Dartmouth soldiers also fought at the Battle of Gettysburg. Three soldiers served in the 1st Regiment MVI, one in the 16th, and 33rd, and six in the 18th.[41]

David Lewis Gifford was a Union Army soldier from Dartmouth, who received the Medal of Honor. He enlisted in December 1863, at age 1— as a member of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment. Following the steamer the USS Boston running aground on an Oyster bed, leaving 400 individuals within range of Confederate artillery. Gifford and four other men—led by George W. Brush—manned a small boat and ferried stranded soldiers to a safe area.[42][43]

1864

[edit]In April 1864, the people of Dartmouth voted to raise money to fill the quota of men for the service. At the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Bradford Little from Dartmouth was wounded, and Edwin C. Tripp from Dartmouth died at the Battle of Cold Harbor. Three Dartmouth men were wounded at the Siege of Petersburg. Thos. C Lapham wrote to his uncle on Chase Road in Dartmouth from General Hospital Number One in Murfreesboro, Tennessee on January 20, 1864. He described the cold weather in what he called ''Old'' Dartmouth, as well as writing about his maladies while serving in the South, and morale among the troops, before sending his regards to his family in Dartmouth. Nahum Nickelson was another resident of Dartmouth who served in the Civil War. He enlisted in the 35th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment as a drummer in March 1864. He trained for five weeks in Boston Harbor before taking a transport ship to Alexandria, Virginia, where he joined the Battle of the Wilderness and the battles in Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. He was mustered out in July 1865. Once returning to Dartmouth, he built a home and would eventually be rewarded the Boston Cane, which was awarded to the oldest living resident in Dartmouth, and would be buried in the Padanaram cemetery, where he used to be a caretaker. Private Humphrey R. Davis (a seaman from Dartmouth) died in May 1864 as a prisoner of war in Andersonville Prison. During the 1864 United States presidential election, 384 people in Dartmouth voted to reelect Abraham Lincoln.[44]

Modern history

[edit]

The Watuppa Branch railroad started to serve Dartmouth in 1875.[45]

During the late 19th century its coastline became a summer resort area for wealthy members of New England society.

Lincoln Park was established in 1894 by the Union Street Railway Co. of New Bedford, and became an amusement park in the mid-20th century with rides such as the wooden roller coaster The Comet.[46]

Round Hill was the site of early-to-mid 20th century research into the uses of radio and microwaves for aviation and communication by MIT scientists, including physicist Robert J. Van de Graaff. There in 1933 he built the world's largest air-insulated Van de Graaff generator (now located at the Museum of Science (Boston)).[47] It is also the site of the Green Mansion, the estate of "Colonel" Edward Howland Robinson Green, a colorful character who was son of the even more colorful and wildly eccentric Hetty Green.[48]

In 1936, the Colonel died. The estate fell into disrepair as litigation over his vast fortune continued for eight years between his widow and his sister. Finally, the court ruled that Mrs. Hetty Sylvia Wilks, the Colonel's sister, was the sole beneficiary. In 1948, she bequeathed the entire estate to MIT, which used it for microwave and laser experiments. The giant antenna, which was a landmark to sailors on Buzzards Bay, was erected on top of a 50,000-gallon water tank. Although efforts were made to preserve the structure, it deteriorated and was demolished on November 19, 2007.

Another antenna was erected next to the mansion and used in the development of the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System. MIT continued to use Round Hill through 1964. It was sold to the Society of Jesus of New England and was used as a retreat house. The upper floors were divided into 64 individual rooms. The main floor was fitted with a chapel, a library, and meeting rooms.

In 1970 the Jesuits sold the land and buildings to Gratia R. Montgomery. In 1981, Mrs. Montgomery sold most of the land to a group of developers who have worked to preserve the history, grandeur and natural environment. The property is now a gated, mostly summer residential community on the water featuring a nine-hole golf course.

In 1980 Sunrise Bakery and Coffee Shop opened its first store in Dartmouth.[49]

The town appeared in national news in 2013 when Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, then a university student at Dartmouth, participated in the Boston Marathon bombing.[50][51]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 97.5 square miles (252.6 km2), of which 60.9 square miles (157.8 km2) is land and 94.8 square kilometres (36.6 sq mi) or, 37.53%, is water.[52] It is the third largest town by area in Massachusetts.[4]

The town is accessible by I-195 and US 6, which run parallel to each other through the northern-main business part of town from New Bedford to Westport on an east-west axis within a mile or two apart from one another.

Dartmouth includes the Southeastern Massachusetts Bioreserve that extends from Fall River into many protected forests of North Dartmouth in the Collins Corner, Faunce Corner, and Hixville sections of town. The Southeastern Massachusetts Bioreserve extends its protected forest lands into the Freetown-Fall River State Forest and beyond.

Numerous rivers flow north-south in Dartmouth, such as the Copicut River, Shingle Island River, Paskamanset River, Slocums River, Destruction Brook, and Little River. Dartmouth is divided into two primary sections: North Dartmouth (USPS ZIP code 02747) and South Dartmouth (USPS ZIP code 02748).

The town is bordered by Westport to the west, New Bedford to the east, Fall River and Freetown to the north, and Buzzards Bay and the Atlantic Ocean to the south.

The highest point in the town is near its northwestern corner, where the elevation rises to over 256 feet (78 m) above sea level north of Old Fall River Road.[53]

Ecology and natural resource management

[edit]

The Lloyd Center for Environmental Studies, located in South Dartmouth, is a non-profit organization that provides educational programs on aquatic environments in southeastern New England. It is across the mouth of the Slocums River from Demarest Lloyd State Park, a popular state beach known for its shallow waters.

The Dartmouth Natural Resource Trust in Dartmouth, is a non-profit land trust incorporated in 1971 working to preserve and protect Dartmouth's natural resources.[55] The trust has protected 5,400 acres of land since 1971 and owns 1,800 acres in Dartmouth as of 2020,[56] including 35 miles of hiking trails, and ocean and river walks. The DNRT is accredited through the Land Trust Accreditation Commission, an independent program of the Land Trust Alliance.[56] The Trust organizes such activities as photography tours, summer outdoor yoga series, bird watching, and plant identification. Its summer evening Barn Bash and winter fundraising auction are held annually. Since 1999, nearly 20 Boy Scouts from four troops have completed Eagle Scout projects through the DNRT.[57][58] The Trust's headquarters building is located on the former Helfand Farm.[59]

Transportation

[edit]Highway

[edit]Route 140 and Route 24 are located just outside Dartmouth's borders in New Bedford and Fall River, respectively, and both provide access to Boston and points north of the area. Route 177 begins just over Dartmouth's border with Westport, running west into Rhode Island and providing a link between the Newport-area (Tiverton, Little Compton, and Aquidneck Island) with the Fall River/New Bedford area. I-195 and US 6 pass directly through Dartmouth, and also offer connections to the aforementioned three Massachusetts routes; the former provides access to Route 140, while the latter can be used to access Route 24 and Route 177.

Both Tiverton, RI and Little Compton, RI are geographically part of Massachusetts, lacking direct interstate highway connections with the rest of Rhode Island. Instead, smaller routes connect to the area (RI 138, MA/RI 24, RI 177/MA 177, and MA 81, and MA 88).[clarification needed] Route 24 lies an average of 15 to 20 miles away in Tiverton, RI and Little Compton, RI, Route 177 and Route 140 and Route 24 are based upon old Indian routes and trails.

Bus

[edit]Public transportation in Dartmouth is primarily provided by the Southeastern Regional Transit Authority, which provides direct bus services between several points in Dartmouth and to the adjacent cities of New Bedford and Fall River.[60] Transfers at either terminus offer connections to T.F. Green Airport via Plymouth & Brockton Street Railway[61] and various locales in Rhode Island via Peter Pan Bus;[62][63] the latter company also offers connections from New Bedford to Cape Cod and Boston.[63] Direct daily bus service from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth to Taunton and Boston was formerly offered via DATTCO buses; this service was cut back to only one express round-trip every Friday in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[64][65]

Water

[edit]Despite its border along Buzzard's Bay, Dartmouth does not have any major water-based transport. However, the adjacent cities of Fall River and New Bedford offer several indirect ferry connections, with routes to Newport and Block Island[66] from the former and Martha's Vineyard,[67] Nantucket,[68] and Cuttyhunk[69] from the latter.

Rail

[edit]While Dartmouth and neighboring communities currently do not have any rail connections, construction of MBTA commuter rail stations is currently underway in Fall River and New Bedford as part of the South Coast Rail project. Upon completion, these will offer railway connections to cities including Taunton, Brockton, Braintree, and Boston.[70]

A short segment of the railway, officially known as the North Dartmouth Industrial Railroad and informally referred to as the Watuppa branch, passes through northern Dartmouth after diverging from the New Bedford Secondary and eventually terminating in the nearby town of Westport. The primary operator of freight rail in Dartmouth is Bay Colony Railroad, which operates along the Watuppa branch and interchanges with Massachusetts Coastal Railroad in New Bedford.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 3,868 | — |

| 1860 | 3,883 | +0.4% |

| 1870 | 3,367 | −13.3% |

| 1880 | 3,430 | +1.9% |

| 1890 | 3,122 | −9.0% |

| 1900 | 3,669 | +17.5% |

| 1910 | 4,378 | +19.3% |

| 1920 | 6,493 | +48.3% |

| 1930 | 8,778 | +35.2% |

| 1940 | 9,011 | +2.7% |

| 1950 | 11,115 | +23.3% |

| 1960 | 14,607 | +31.4% |

| 1970 | 18,800 | +28.7% |

| 1980 | 23,966 | +27.5% |

| 1990 | 27,244 | +13.7% |

| 2000 | 30,666 | +12.6% |

| 2010 | 34,032 | +11.0% |

| 2020 | 33,783 | −0.7% |

| 2022 | 33,406 | −1.1% |

Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81] | ||

Government

[edit]Local government

[edit]Since 1928, Dartmouth has been governed by a representative town meeting, its legislative body, and Select Board, its executive body. Prior to 1928, the town was governed by an open town meeting.[82] The Town Hall is located in the former Poole School, which also served as Dartmouth High School for several years. The town is patrolled by a central police department, located near Smith Mills on the site of the former Job S. Gidley School. There are five fire stations in the town divided among three fire districts, all of which are paid-call departments. There are two post offices (North Dartmouth, under the 02747 ZIP Code, and South Dartmouth, under the 02748 ZIP Code).

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of February 12, 2020[83] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |||

| Unenrolled | 13,113 | 57.4% | |||

| Democrat | 6,950 | 30.4% | |||

| Republican | 2,433 | 10.6% | |||

| Green | 20 | 0.00088% | |||

| Libertarian | 93 | 0.004% | |||

| Total | 22,849 | 100% | |||

County government

[edit]The Bristol County Sheriff's Office maintains its administrative headquarters and operates several jail facilities in the Dartmouth Complex in North Dartmouth in Dartmouth. Jail facilities in the Dartmouth Complex include the Bristol County House Of Correction and Jail, the Bristol County Sheriff's Office Women's Center, and the C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center.[84]

State & national government

[edit]Dartmouth is located in the Ninth Bristol state representative district, which includes all of Dartmouth as well as parts of Freetown, Lakeville, and New Bedford. The current state representative is Christopher Markey. The town is represented by Mark Montigny in the state senate in the Second Bristol and Plymouth district, which includes the city of New Bedford and the towns of Acushnet, Dartmouth, Fairhaven, and Mattapoisett. Dartmouth is the home of the Third Barracks of Troop D of the Massachusetts State Police, which relocated in 2006 from Route 6 to just north of the retail center of town on Faunce Corner Road. On the national level, the town is part of Massachusetts Congressional District 9, which is represented by William R. Keating. The state's junior (Class I) Senator is Ed Markey and the state's senior (Class II) Senator, is Elizabeth Warren.

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third parties | Total Votes | Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 54.75% 9,792 | 43.49% 7,778 | 1.76% 314 | 17,884 | 11.26% |

| 2016 | 53.06% 8,586 | 41.64% 6,738 | 5.31% 859 | 16,183 | 11.42% |

| 2012 | 61.21% 9,880 | 37.08% 5,985 | 1.72% 277 | 16,142 | 24.13% |

| 2008 | 62.39% 10,442 | 35.11% 5,876 | 2.50% 419 | 16,737 | 27.28% |

| 2004 | 67.16% 10,218 | 31.91% 4,855 | 0.93% 142 | 15,215 | 35.25% |

| 2000 | 65.06% 8,800 | 28.95% 3,916 | 5.99% 810 | 13,526 | 36.11% |

| 1996 | 64.16% 7,852 | 24.65% 3,017 | 11.19% 1,370 | 12,239 | 39.50% |

| 1992 | 51.12% 6,571 | 22.14% 2,846 | 26.74% 3,437 | 12,854 | 24.38% |

| 1988 | 56.27% 6,563 | 42.94% 5,009 | 0.79% 92 | 11,664 | 13.32% |

| 1984 | 48.29% 5,355 | 51.36% 5,695 | 0.35% 39 | 11,089 | 3.07% |

| 1980 | 38.13% 4,044 | 46.52% 4,934 | 15.35% 1,628 | 10,606 | 8.39% |

| 1976 | 53.72% 5,314 | 42.88% 4,242 | 3.40% 336 | 9,892 | 10.84% |

| 1972 | 50.32% 4,975 | 48.84% 4,828 | 0.84% 83 | 9,886 | 1.49% |

| 1968 | 54.61% 4,738 | 41.38% 3,590 | 4.01% 348 | 8,676 | 13.23% |

| 1964 | 67.75% 5,392 | 31.52% 2,509 | 0.73% 58 | 7,959 | 36.22% |

| 1960 | 57.26% 4,292 | 42.61% 3,194 | 0.13% 10 | 7,496 | 14.65% |

| 1956 | 34.93% 2,328 | 64.65% 4,309 | 0.42% 28 | 6,665 | 29.72% |

| 1952 | 39.25% 2,323 | 60.41% 3,575 | 0.34% 20 | 5,918 | 21.16% |

| 1948 | 46.51% 2,047 | 49.31% 2,170 | 4.18% 184 | 4,401 | 2.79% |

| 1944 | 49.23% 1,832 | 50.66% 1,885 | 0.11% 4 | 3,721 | 1.42% |

| 1940 | 51.49% 1,878 | 48.15% 1,756 | 0.36% 13 | 3,647 | 3.35% |

Libraries

[edit]

Dartmouth established public library services in 1895.[86][87] Today there are two libraries, the Southworth (Main) Library in South Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Public Library—North Branch. The Southworth Library is part of the Sails Library Network, and shares a name with an older library.[88] The older library, also called Southworth, was founded in 1878, by the pastor of the Congregational Church of South Dartmouth. The location of the Old Southworth library was purchased in 1888, and dedicated in 1890, due to funds from John Haywood Southworth—who furnished the library with 2,500 books in memory of his father. At the time the library required the purchase of a 50 cent library card to borrow books. The library was acquired by the town of Dartmouth in 1927. The building lacked space to contain books by 1958, and in April 1967 it was voted upon to build a new library with $515,000 on Dartmouth Street.[89] In fiscal year 2008, the town of Dartmouth spent 1.5% ($865,864) of its budget on its public libraries—approximately $25 per person.[90] Additionally, the Dartmouth Free Public library existed in Russells Mills, moving to various locations throughout the area—catering mostly to children at the local schools there.[91]

Education

[edit]

Dartmouth is governed by a single school department whose headquarters are in the former Bush Street School in Padanaram. The school department has been experiencing many changes in the past decade, with the opening of a new high school, and the moving of the former Middle School to the High School. The town currently has four elementary schools, Joseph P. DeMello, George H. Potter, James M. Quinn, and Andrew B. Cushman. The town has one middle school (located in the 1955-vintage High School building) next to the Town Hall, and one high school, the new Dartmouth High School, which opened in 2002 in the southern part of town. Its colors are Dartmouth green and white, and its fight song is "Glory to Dartmouth;" unlike the college, however, the school still uses the "Indians" nickname, with a stylized brave's head in profile as the logo which represents the Eastern Woodland Natives that first inhabited the area.

In addition to DHS, students may also attend Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational-Technical High School or Bristol County Agricultural High School. The town is also home to private schools including Bishop Stang, and Friends Academy.

Since the 1960s, Dartmouth has been home to the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus, located on Old Westport Road, just southwest of the Smith Mills section of town. The campus was the result of the unification of the Bradford Durfee College of Technology in Fall River and the New Bedford Institute of Textiles and Technology in New Bedford in 1962 to form the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute. The campus itself was begun in 1964 and its unique Brutalist design was created by Paul Rudolph, then the head of Yale's School of Architecture. From 1969 until its inclusion into the University of Massachusetts system in 1991, the school was known as Southeastern Massachusetts University, reflecting the school's expansion into liberal arts. The campus has expanded over the years to its current size, with several sub-centers located in Fall River and New Bedford.

Culture

[edit]Notable artists associated with Dartmouth include Beatrice Chanler, Dwight William Tryon, Ernest Ludvig Ipsen, and Pete Souza.

Dartmouth Community Band

[edit]The Dartmouth Community Band was established in 1974.[92] The band plays regular summer concerts in Apponagansett Park as a part of the Dartmouth Parks and Rec. Summer Concert Series.[93]

Notable people

[edit]- Frederic Vaughan Abbot (1858–1928), U.S. Army brigadier general (summer resident)[94]

- Naseer Aruri (1934–2015), internationally recognized scholar-activist and expert on Middle East politics, U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and human rights

- Ezekiel Cornell (1732–1800), member of Continental Congress 1780–1782

- Henry H. Crapo (1804–1869), 14th Governor of Michigan

- William W. Crapo (1830–1926, U.S. House Representative representing Massachusetts' 1st District

- David Lewis Gifford (1844–1904), U.S Medal of Honor recipient, regarding his service during the American Civil War

- Arthur Golden (born 1956), author, Memoirs of a Geisha (summer resident)

- Edward Howland Robinson Green (1868–1936), a businessman

- Edith Ellen Greenwood (born 1920), the first female recipient of the Soldier's Medal

- Huda Kattan (born 1983), CEO of Huda Beauty[95]

- Téa Leoni (born 1966), film and television actress (summer resident)

- Arthur Lynch (born 1990), former football tight end for the Miami Dolphins

- Lewis Lee Millett Sr., recipient of Congressional Medal of Honor (Korean War)

- Brian Rose (born in 1976), a former Major League Baseball player

- Philip Sheridan (1831–1888), Union general in the American Civil War who died at his summer home in Nonquitt

- Peleg Slocum (1654–1733), Quaker and proprietor of Dartmouth[96]

- Pete Souza (born 1954), former Chief Official White House Photographer (2009–2017), grew up in Dartmouth[97]

- Jordan Todman (born 1990), was a football running back for six NFL teams

- Bernard Trafford (1871–1942), football player for Harvard University and chairman of First National Bank of Boston[98]

- Benjamin Tucker (1854–1939), individualist, anarchist and egoist; English translator of the works of Max Stirner

- Donald Eugene Webb (1931–1999), longest fugitive on the FBI's Most Wanted List and prime suspect in the murder of a Pennsylvania police chief who made headlines in 2017 when his remains were discovered buried in his wife's backyard.

In popular culture

[edit]- The Terror Factor, a 2007 horror comedy film, is set in Dartmouth.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ricketson, Daniel (1858). The history of New Bedford, Bristol County, Massachusetts including a history of the old township of Dartmouth and the present townships of Westport, Dartmouth, and Fairhaven, from their settlement to the present time. D. Ricketson. p. 13. OCLC 1263627689.

- ^ GUHA, AUDITI. "Dartmouth's rich 350-year history". southcoasttoday.com. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Dartmouth town, Bristol County, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Silva, Lurdes C. da. "Azorean city of Lagoa to celebrate its 500 years with local Sister Cities, special exhibition to open May 13 in Dartmouth". Fall River Herald News. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Wall, Barry W. (2003). A History of the Diocese of Fall River. Strasbourg, France: Editions de Signe. pp. 81, 102, 103. ISBN 2-7468-1253-3.

- ^ a b Comiskey, Kathleen Ryan (1976). Secrets of Old Dartmouth (Revised ed.). New Bedford, Massachusetts: Reynolds-DeWalt. p. 31.

- ^ a b c "The Old Dartmouth Purchase | New Bedford Whaling Museum". February 3, 2020. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ "Evolution of Old Dartmouth - New Bedford Whaling Museum". www.whalingmuseum.org. March 12, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Barboza, Robert. "Genealogist brings 'missing' Wampanoag history in Westport, Dartmouth to forefront". southcoasttoday.com. New Bedford. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2001). Dartmouth: The Early History of a Massachusetts Coastal Town. New Bedford, MA: American Printing. p. 49. ISBN 978-0971459106.

- ^ Museum, New Bedford Whaling. "Exploration & "Discovery"". New Bedford Whaling Museum. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ Comiskey, Kathleen Ryan (1976). Secrets of Old Dartmouth (Revised ed.). New Bedford, Massachusetts: Reynolds-DeWalt. pp. 23–25.

- ^ a b "A Brief History | Dartmouth, MA". www.town.dartmouth.ma.us. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "A Deed Appointed to be Recorded". Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "A Deed Appointed to be Recorded. | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower. Penguin, 2006. p.171 ISBN 978-0-14-311197-9

- ^ "The Old Dartmouth Purchase". New Bedford Whaling Museum. February 3, 2020. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ a b "A Brief History". Town of Dartmouth MA. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "Evolution of Old Dartmouth". New Bedford Whaling Museum. March 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2001). Dartmouth: The Early History of a Massachusetts Coastal Town. New Bedford, MA: American Printing. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0971459106.

- ^ Comiskey, Kathleen Ryan (1976). Secrets of Old Dartmouth (Revised ed.). New Bedford, Massachusetts: Reynolds-DeWalt. p. 35.

- ^ a b Wittenberg, Ariel. "The story of Dartmouth's first settlers: The Quakers". southcoasttoday.com. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lukesh, Susan Snow (February 15, 2016). Frozen in Time: An Early Carte de Visite Album from New Bedford, Massachusetts. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-4834-3920-4.

- ^ Ricketson, Daniel (1858). The history of New Bedford, Bristol County, Massachusetts including a history of the old township of Dartmouth and the present townships of Westport, Dartmouth, and Fairhaven, from their settlement to the present time. D. Ricketson. OCLC 1263627689.

- ^ "The Old Dartmouth Purchase". New Bedford Whaling Museum. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Arato, Christine A.; Eleey, Patrick L. (1998). Safety Moored at Last: History, existing conditions, analysis, preliminary preservation issues. National Park Service. ISBN 978-0-912627-66-3.

- ^ "Conflict - Irreconcilable Differences". New Bedford Whaling Museum. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Staff Writer. "1675: When Dartmouth was at War". New Bedford Standard-Times. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2001). Dartmouth: The Early History of a Massachusetts Coastal Town. New Bedford, MA: American Printing. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-0971459106.

- ^ Barboza, Robert (2014). Patriots of Old Dartmouth. Vineyard Sound Books. ISBN 978-0-9825075-6-8.

- ^ a b Medeiros, Peggi. "Akin House: The Elihu Akin House Narrative". Roger Williams University.

- ^ "Guest views: Preserving Dartmouth's 1762 Elihu Akin House". New Bedford Standard-Times. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ^ "Akin House". rwu.shorthandstories.com. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Robinson, Kate (October 23, 2020). "Dartmouth during the American Revolution". Dartmouth the Week Today. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ^ Sousa, Ron. "Russells Mills Village Historic Tours".

- ^ Sawtell, Clement Cleveland (1962). The Ship Ann Alexander of New Bedford: 1805-1851. Marine Historical Association.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2004). Three Hundred and Fifty-Five Men for the Union. New Bedford, MA: Command Print Solutions. pp. 1–10.

- ^ a b Glennon, Beverly (October 2004). Three Hundred and Fifty-Five Men for the Union. New Bedford, MA: Command Print Solutions. pp. 15–37.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2004). Three Hundred and Fifty-Five Men for the Union. New Bedford, MA: Command Print Solutions. pp. 40–47.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2004). Three Hundred and Fifty-Five Men for the Union. New Bedford, MA: Command Print Solutions. pp. 50–60.

- ^ Browne, Patrick (January 28, 2019). "Dartmouth". Massachusetts Civil War Monuments Project. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ "Valor awards for David L. Gifford". August 12, 2014. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2004). Three Hundred and Fifty-Five Men for the Union. New Bedford, MA: Command Print Solutions. pp. 60–63, 85.

- ^ Glennon, Beverly (October 2004). Three Hundred and Fifty-Five Men for the Union. New Bedford, MA: Command Print Solutions. p. 1.

- ^ "Lincoln Park's Comet roller coaster demolished today in Dartmouth, evoking memories of thrills past". www.boston.com. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Robert Van de Graaff - Scientist of the Day". Linda Hall Library. December 20, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "The Peculiar Story of the Witch of Wall Street". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ GazelleGazelle (January 24, 2023). "Sunrise Bakery For Sale After 42 Years in New Bedford, Dartmouth". FUN 107. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Bombings Update: Suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was on U-Mass-Dartmouth campus this week, classmates say". www.cbsnews.com. April 19, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Parker, Diantha; Bidgood, Jess (January 1, 2015). "Boston Marathon Bombing: What We Know". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Dartmouth town, Bristol County, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Fall River, MA 7.5 by 15-minute quadrangle, 1985.

- ^ "Slocum's River Reserve | Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust (DNRT)". July 25, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "DNRT renews accreditation, protects over 1,800 acres". southcoasttoday.com. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Eagle Scouts improve Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust properties". The Herald News, Fall River, MA. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "DNRT's annual Barn Bash raised more than $25,000". southcoasttoday.com. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Community garden offers plots to SouthCoast residents". southcoasttoday.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "New Bedford Route Schedules". Southeastern Regional Transit Authority. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ "T.F. Green Service". Plymouth & Brockton Street Railway. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ "Fall River station". Peter Pan Bus. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Peter Pan Bus Lines". Destination New Bedford. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "SouthCoast – Boston Express". DATTCO. 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "DATTCO Bus: UMassD to Boston". University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ "Fall River Hi-Speed Schedule". Block Island Ferry. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ "New Bedford to Martha's Vineyard Ferry". SeaStreak.

- ^ "New Bedford to Nantucket Ferry". SeaStreak.

- ^ "Cuttyhunk Ferry Company". The Cuttyhunk Ferry Company.

- ^ "South Coast Rail". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020−2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "1927 Chap. 0026. An Act Providing For Precinct Voting, Representative Town Meetings, Town Meeting Members, A Referendum And A Moderator To Serve For A Year In The Town Of Dartmouth". archives.lib.state.ma.us. Secretary of the Commonwealth. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ https://www.sec.state.ma.us/ele/elepdf/enrollment_count_20200212.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Facilities." Bristol County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved on January 30, 2012. "400 Faunce Corner Road, Dartmouth, MA 0274" and "Bristol County House Of Correction and Jail 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747" and "Bristol County Sheriff's Office Women's Center 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747" and "C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center: 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747"

- ^ "Election Results".

- ^ Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. v.9 (1899).

- ^ http://www.dartmouthpubliclibraries.org Archived August 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Dartmouth Public Libraries Retrieved November 11, 2010

- ^ "Southworth Library -- Dartmouth Public Libraries". librarytechnology.org. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Shelford, Chloe. "The storied history of the Old Southworth Library". Dartmouth. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ July 1, 2007, through June 30, 2008; cf. The FY2008 Municipal Pie: What's Your Share? Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Board of Library Commissioners. Boston: 2009. Available: Municipal Pie Reports Archived January 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 4, 2010

- ^ Haskell, Elsie. "History of the Dartmouth Public Libraries" (PDF).

- ^ "Community band ready for summer of shows". Dartmouth Week. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

The band was first formed in 1974

- ^ "Dartmouth Community Band | Town of Dartmouth MA". www.town.dartmouth.ma.us. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ "Colonel Frederick V. Abbot, Famed Engineer Of The World War, Is Dead". The Yonkers Herald. Yonkers, NY. September 27, 1928. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Makeup Mogul Probably Loves Dartmouth Pizza Joint as Much as You". March 3, 2019.

- ^ "Old Dartmouth Historical Sketch No. 3 - New Bedford Whaling Museum". www.whalingmuseum.org. November 24, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Bio". www.petesouza.com.

- ^ "B. Trafford Dead; Boston Banker, 71". The New York Times. January 3, 1942. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Resident and Business Directory of Dartmouth, Westport and Acushnet Massachusetts, 1905. Hopkinton, Mass.: A. E. Foss. 1905. OCLC 48412957. OL 14038546M.

- Glennon, Beverly Morrison (2001). Dartmouth: The Early History of a Massachusetts Coastal Town. Dartmouth, Mass.: B. M. Glennon. ISBN 0-9714591-0-X. OCLC 50841507.