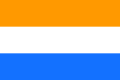

Flag of South Africa (1928–1994)

| |

| "Oranje, Blanje, Blou"[1] "Union flag"[2][3] "Apartheid flag"[4] | |

| Use | National flag, civil and state ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 31 May 1928 (dark version) 1982 (bright version) |

| Relinquished | 21 March 1990 (South West Africa) 20 April 1994 (South Africa) |

| Design | Three horizontal bands of orange, white and blue with three small flags (the Union Jack to the left, the vertical version of the flag of the Orange Free State in the centre and the flag of the South African Republic to the right) centered on the white band. |

The flag of South Africa from 1928 to 1994 was the flag of the Union of South Africa from 1928 to 1961 and later the flag of the Republic of South Africa until 1994. It was also the flag for South West Africa (now Namibia) under the former's administration (until 1990). Based on the Dutch Prince's Flag, it contained the flag of the United Kingdom, the flag of the Orange Free State, and the flag of the South African Republic (respectively) in the centre.[5] A nickname for the flag was Oranje, Blanje, Blou (Afrikaans for: "orange, white, blue").[1]

It was adopted in 1928 by an act of Parliament from the first Afrikaner majority government, as a compromise between the Afrikaner and British populations. In 1948, after their election victory, the National Party unsuccessfully tried to amend the flag design to remove what they called the "Blood Stain" (the flag of the United Kingdom).[6] After South Africa became a republic in 1961, the flag was retained as the national flag, despite the country having left the Commonwealth. In 1968, Prime Minister John Vorster proposed that a new national flag for South Africa be adopted in 1971 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the declaration of a republic.[7] However, Vorster's idea did not gain parliamentary support and the flag change never happened. As a result, it was the national flag during apartheid (1948–1994), and it is also known as the "Apartheid flag".[4][6] It was replaced by the current flag of South Africa in 1994 with the commencement of the country's transitional constitution and the end of apartheid.

Following its retirement in 1994, the flag has been controversial within South Africa, with some viewing it as historic and a symbol of Afrikaner heritage, while others view it as a symbol of apartheid and white supremacy. In 2023, the Supreme Court of Appeal upheld that "gratuitous" displays of the flag constituted hate speech; exceptions have been allowed for "cases of journalistic, academic and artistic expression" and for museums and places of historical interest.[8][9]

Adoption

[edit]

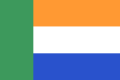

Before 31 May 1928 the only flag that had official status in the Union of South Africa was the United Kingdom's Union Jack as South Africa was part of the British Empire. The South African Red Ensign was used as an unofficial flag. In 1925, discussion rose about creating a new flag for South Africa as many descendants of Boers found the Union Jack unacceptable after the Second Boer War.[10] In 1926 the Balfour Declaration granted South Africa legislative autonomy, opening the possibility of a new flag. British South Africans wanted the Union Jack in the new flag as part of the British Empire while the Afrikaners did not. The majority British Natal Province threatened to secede from the Union if the Union Jack was removed.[10] A compromise was reached whereby the new flag would consist of the Prinsenvlag as this was the first flag raised on South Africa and a badge in the centre consisting of the Union Jack with the flags of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic.[10][11] The Union Jack was mirrored in the new flag with the hoist on the right so that it did not take precedence over the others.[12] This was denounced by D. F. Malan, then the South African Minister of Home Affairs, who described the group of miniature flags "a scab... which will one day fall off".[13] The South African Red Ensign would be retained as South Africa's merchant ensign until 1951.[14]

In 1927, the Afrikaner-majority Parliament of South Africa passed the Union Nationality and Flag Act, which stated that the Union Jack and the new flag of the Union of South Africa were to have equal status as the flag of South Africa. The act came into force in 1928 when both flags were raised over the Houses of Parliament, Cape Town and the Union Buildings in Pretoria.[15] This dual status was ended in 1957 with the passing of the Flags Amendment Act which declared that the Oranje, Blanje, Blou would be the sole flag of South Africa, with the act also declaring that "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" would be the country's sole anthem and dropping "God Save the Queen".[10]

When South Africa became a republic in 1961, the flag remained the same. The Afrikaner voting majority disliked the flag retaining the Union Jack in the centre. Repeated calls were made for it to be removed or for a new flag but no action was taken by the ruling National Party until 1968. Prime Minister B. J. Vorster convened a commission in that year to create a new flag in time for the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the republic in 1971, but no changes were eventually made.[7]

The flag was treated with respect by Afrikaners, with daily flag salutes in schools.[16] It was also used as part of celebrations of the inauguration of the State President.[17] The flag even had an ode dedicated to it, "Vlaglied" (English: "Flag Song"),[18][19][20] written by Cornelis Jacobus Langenhoven[19] and composed by F.J. Joubert.[19][21]

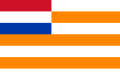

Due to variances in manufacturing, many flags were manufactured with their blue a dark shade akin to that found on the flag of the UK, as many early flags were made in the UK. Because of this discrepancy, in 1982, the South African government specified that "Solway blue", a lighter shade of blue, be used on the flags as was originally intended.[22][23]

The flag was featured on the cantons of the flags of government agencies such the military, prisons service, and police.[24] After the flag was retired in 1994, the new South African flag replaced it on those flags' cantons.[24]

Opposition

[edit]Despite the flag's origins and adoption pre-dating the National Party's ascension to power by twenty years, the flag gradually became associated with the apartheid regime. Movements like the Black Sash[25] and uMkhonto we Sizwe[26] started protesting against it with their own symbols. Often, the flag of South Africa would be removed from public display and replaced with the banned ANC flag.[26] The flag would also be the subject of public burnings during anti-apartheid protests.[27][28]

After 1989, F. W. de Klerk became state president and immediately unbanned the African National Congress (ANC) and released their leader, Nelson Mandela, from prison. De Klerk instigated negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa with Mandela's ANC. One of the ANC's demands was that the flag gradually decrease in usage in South African life and that a new flag be created, as black South Africans associated the current one with apartheid and Afrikaner nationalism.[29]

The negotiations led to the 1992 South African apartheid referendum where the white part of the South African populace (all other groups still being disenfranchised) voted to end apartheid. The referendum decision resulted in the International Rugby Football Board allowing the South African rugby team to play test matches again. The ANC agreed to endorse the team on the condition that the flag not be used to represent South Africa. During the return test, the Conservative Party handed out numerous flags to the majority white crowd as a symbol of defiance against the ANC.[30] At the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, the South African team performed under a specially designed flag for the National Olympic Committee of South Africa, although white South African spectators at the games waved the then national flag, despite attempts by officials to stop them.[31]

In 1994, the State Herald of South Africa, Fred Brownell, was approached to design a new national flag for South Africa to replace the flag in time for the first elections after apartheid. He designed the new flag of South Africa with a combination of the old flag and the colours of the ANC flag.[32] The new flag design was approved personally by both de Klerk and Mandela before being unanimously approved by the Transitional Executive Council on 15 March 1994.

De Klerk made the public proclamation of the replacement of the old flag on 20 April, seven days before the 1994 South African general election on 27 April 1994.[32] When the flag was lowered for the last time at the parliament building in Cape Town, anti-apartheid onlookers approvingly shouted "Down, down!" as it was removed.[33][34]

After 1994

[edit]

Following its official retirement as the flag of South Africa, the flag was adopted by some white South Africans as being a symbol of Afrikaner heritage and history.[1] Many South Africans still view it as a symbol of apartheid and therefore have strongly discouraged its use.[35] Despite the negative associations, it was never banned by the Government of South Africa post-1994, and the right to display it in South Africa was protected under Chapter Two of the Constitution of South Africa as an expression of free speech[36] until 2019.[9] In the 21st century, the flag experienced use as a symbol by white supremacists in and outside South Africa.[37][38] A particular awareness of this followed the shooting of black parishioners at a Charleston, South Carolina church in 2015, as the perpetrator, Dylann Roof, had previously been pictured wearing a jacket with two flag patches of the flag and the flag of white-ruled Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) attached on it.[39] This association with apartheid and racism often led to calls for the flags that were used in a historical context to be removed from display. An example of this is in Cooma, Australia, where until 2023 it was flown to commemorate South African workers in the Snowy Mountains Scheme alongside the Canadian Red Ensign, 49-star US flag, and other flags from 1959 when the Avenue was dedicated.[40][41]

The flag has also been used as a symbol of protest post-1994.[42] In 2005, a statue of Venda King Makhado was vandalised in Louis Trichardt with the colours of the flag as a protest against a proposal to change the name of the town to Makhado.[43] Some South Africans in the 21st century started to fly the flag as a protest against what they perceived as the failure of the ANC to make progress in governing South Africa as a democracy.[44]

At Cape Town's Castle of Good Hope, the flag was flown from the castle alongside the Union Jack, flag of the Netherlands and the current flag of South Africa to display the powers that ruled South Africa through history. In 1994, it was agreed that they would remain on the castle parapet as historical reference. However, in 2012, following complaints from the ANC member of parliament Nomfunelo Mabedla, all the flags apart from the current flag of South Africa were removed from the parapet, and the removed flags were placed in the castle's museum.[45] The flag is also collected in some other museums in South Africa, including the South African Naval Museum.

In 2008, the flag was mistakenly put on posters in Ghana advertising that year's Africa Cup of Nations, sparking indignation among some South Africans.[4][46]

The flag was declared illegal for public display in South Africa in August 2019, when the Equality Court classified it as hate speech, with heavy enforcing penalties. Exceptions were made for academic, journalistic & artistic expression and museums & places of historical interest. Judge Phineas Mojapelo declared that "Displaying [the apartheid flag] is destructive of our nascent non-racial democracy… it is an affront to the spirit and values of botho / ubuntu, which has become a mark of civilized interaction in post-apartheid South Africa".[9] When AfriForum appealed the ban in the Supreme Court of Appeal in 2022, respondents represented by advocate Ngcukaitobi argued that the flag was meant to unite white South Africans against the native population, and that it was invented by the architects of apartheid to represent racial segregation.[47] Mark Oppenheimer, a lawyer for AfriForum, argued that use of the flag is not necessarily an endorsement of apartheid.[48] In 2023, the ban was partially upheld by the Supreme Court which ruled that "gratuitous" display was unlawful but did not rule on if private display was unlawful.[8]

Gallery

[edit]-

Flag from 1928–1982

54 years of use -

Flag from 1982–1994

12 years of use -

Prince's Flag

-

The flags of the UK, Orange Free State and South African Republic, as centre motif of the national flag used from 1928 to 1982

-

The flags of the UK, Orange Free State and South African Republic, as centre motif of the national flag used from 1982 to 1994

-

Uncommon 1:2 version, seen on "South Africa Marches On (1941)"[49]

-

Flag of South Africa (1928–1994) without Union Jack used by Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging

- The multiple flags on the South African flag

-

Mirrored 2:3 version of the flag of the United Kingdom

(left) -

Flag of the Orange Free State

(middle) -

Flag of the South African Republic

(right)

- Other relevant flags

-

Afrikaner Vryheidsvlag, used by Afrikaner Volksfront

(left)

See also

[edit]- Coat of arms of South Africa (1910–2000)

- "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika"

- Flag of Rhodesia

- Flag of South Africa, the successor

- List of South African flags

- List of symbols designated by the Anti-Defamation League as hate symbols

- South African Red Ensign, the predecessor

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Merten, Marianne (13 April 2015). "Post-Statue SA: What will be left when the toppling is done?". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Dickens, Peter (15 March 2017). "The inconvenient and unknown history of South Africa's national flags". The Observation Post. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "How an old Dutch flag became a racist symbol". The Economist. 22 June 2015. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "Apartheid flag gaffe sparks row". BBC News. United Kingdom: British Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2008.

- ^ "How an old Dutch flag became a racist symbol". The Economist. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ a b Dickens, Peter (15 March 2017). "The inconvenient and unknown history of South Africa's national flags". The Observation Post. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Lord Graham quits Smith Cabinet as right-wing anger grows". The Glasgow Herald. Vol. 186 (197 ed.). 12 September 1968. pp. 1, 18. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ a b Imray, Gerald (21 April 2023). "Court upholds ban on South Africa's apartheid-era flag". Associated Press. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Head, Tom (21 August 2019). "It's now 'illegal' to display the apartheid flag in South Africa". The South African. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d "South Africa (1928-1994)". Crwflags.com. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "South African Election Special, 2". C-SPAN.org.

- ^ "South Africa (1928–1994)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ South African Tragedy: The Life and Times of Jan Hofmeyr, Alan Paton, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1966, page 102

- ^ Merchant Shipping Act 1951 (South Africa); South Africa Government Gazette No 6085 dated 25 July 1958.

- ^ "1927. Union Nationality & Flag Act". The O'Malley Archives. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Vegter, Ivo (10 December 2013). "My old South African Flag". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "De Klerk Sworn In, Pledges S. African Reforms". Los Angeles Times. 21 September 1989. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ TheKhanate (13 June 2016). "Flag anthem of South Africa(1961-1994): "Vlaglied"". Retrieved 1 November 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c "South Africa - flag songs". www.crwflags.com. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ "'Vlaglied' Copyright Act, 1974" (PDF). South Africa: Republic of South Africa. 1974. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "'Vlaglied' Copyright Act of 1974" (PDF). South Africa. 26 February 1974. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Southern African Vexillological Association Flag Specification Sheet 1: South Africa, National flag 1928-1994" (PDF). 8 June 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Southern African Vexillological Association Flag Specification Sheet 2: South Africa, National flag 1928-1994" (PDF). 8 June 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2018.

- ^ a b "South African Police Service". www.crwflags.com. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "South Africa Women and Apartheid". Photius.com. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ a b Gerhart, Gail (2010). From Protest to Challenge: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882-1990. Indiana University Press. p. 516. ISBN 978-0253354228.

- ^ Jungwirth, Craig (5 April 1985). "Police arrest nine in protest march". The Tech. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "African National Congress supporters set a South African flag on fire..." Getty Images.

- ^ Buhlungu, Sakhela (1997). State of the Nation: South Africa 2007. A&C Black. p. 414. ISBN 0718500725.

- ^ Black, David Ross (1998). Rugby and the South African Nation. Manchester University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0719049326.

- ^ Larson, James (1995). Television in the Olympics. James F. Larson. p. 228. ISBN 0861965388.

- ^ a b "Fred Brownell: The man who made South Africa's flag". BBC News. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Unity Flag Shows Its Colors". Chicago Sun-Times. 27 April 1994. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018.

- ^ Coppola, Antonio (24 May 2018). "Raising of the New South African Flag" – via YouTube.

- ^ Van der Westhuizen, Christi (2007). White Power & the Rise and Fall of the National Party. Zebra Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-1770073050.

- ^ "Old flag still legal". News24.com. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "South Africans supporting the white supremacist Afrikaner Resistance..." Getty Images.

- ^ Sanburn, Josh (18 June 2015). "Dylann Roof Wears Flag Linked to White Supremacy Groups". Time. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Baumann, Nick (18 June 2015). "Dylann Roof Had A Rhodesian Flag on His Jacket - Here's What That Tells Us". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Beech, Alexandra (5 August 2015). "South Africa's apartheid-era flag to keep flying at Cooma's Avenue of Flags: Mayor". ABC News. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Apartheid-era South African flag to fly no more over NSW country town". ABC News. 11 October 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "The Shadow of the Oranje Blanje Blou At #BlackMonday". 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "King's statue vandalised". News24.com. 14 September 2005. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Kiva, Mpumi (13 March 2015). "Why we fly old flag at our Cape home". IOL. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Row erupts over Castle flags". IOL. 30 November 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Ghana poster an 'embarrassment' to SA". GhanaWeb. 10 February 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Staff Reporter (11 May 2022). "Apartheid flag sought to disempower SA's native population". power987.co.za. POWER News. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Evans, Jenni. "Blanket ban on display of old SA flag is 'overbanning' - AfriForum". News24. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "South Africa Marches on (1941)". YouTube.

External links

[edit] Media related to Flags of South Africa (1928–1994) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flags of South Africa (1928–1994) at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of apartheid flag at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of apartheid flag at Wiktionary

![Uncommon 1:2 version, seen on "South Africa Marches On (1941)"[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Flag_of_South_Africa_%281928%E2%80%931982%2C_1-2%29.svg/120px-Flag_of_South_Africa_%281928%E2%80%931982%2C_1-2%29.svg.png)