Pearl Harbor (film)

| Pearl Harbor | |

|---|---|

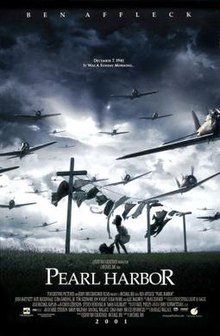

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Bay |

| Written by | Randall Wallace |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Schwartzman |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 183 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $140 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $449.2 million[2] |

Pearl Harbor is a 2001 American romantic period war drama film directed by Michael Bay, produced by Bay and Jerry Bruckheimer and written by Randall Wallace. It stars Ben Affleck, Kate Beckinsale, Josh Hartnett, Cuba Gooding Jr., Tom Sizemore, Jon Voight, Colm Feore, and Alec Baldwin. The film is based on the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the Doolittle Raid.

Despite receiving generally negative reviews from critics, the film was a major box office success, earning $59 million in its opening weekend and, in the end, nearly $450 million worldwide.[2] It was nominated for four Academy Awards, winning in the category of Best Sound Editing. However, it was also nominated for six Golden Raspberry Awards, including Worst Picture. This marked the first occurrence of a Worst Picture-nominated film winning an Academy Award.

Plot

In 1923 Tennessee, two best friends, Rafe McCawley and Danny Walker, play together in the back of an old biplane, pretending to be soldiers fighting the German Empire in World War I. After Rafe's father lands his biplane and leaves, Rafe and Danny climb into the plane. Rafe accidentally starts it, but manages to stop the plane at the end of the runway. Enraged, Danny's father beats his son. Rafe stands up to him, calling him a "dirty German". However, Danny's father reveals that he fought the Germans in France during World War I, and hopes the boys never see the horrors he saw.

In January 1941, with World War II raging, Danny and Rafe are both first lieutenants under the command of Major Jimmy Doolittle. Doolittle informs Rafe that he has been accepted into the Eagle Squadron (a RAF outfit for American pilots during the Battle of Britain). A nurse named Evelyn meets Rafe, who passes his medical exam despite his dyslexia. That night, Rafe and Evelyn enjoy an evening of dancing at a nightclub and later a jaunt in the New York harbor in a borrowed police boat. Rafe shocks Evelyn by saying that he has joined the Eagle Squadron and is leaving the next day.

Rafe is shot down in the English Channel and is presumed killed in action. Evelyn mourns his death and turns to Danny, which spurs a new romance between the two.

On the night of December 6, Evelyn is shocked to discover Rafe standing outside her door, having survived his downing and spending the ensuing months trapped in Nazi-occupied France. Rafe, in turn, discovers Danny's romance with Evelyn and leaves for the Hula bar, where he is welcomed back by his overjoyed fellow pilots. Danny finds a drunken Rafe in the bar with the intention of making things right, but the two get into a fight. They drive away, avoiding being put in the brig when the military police arrive at the bar. The two later fall asleep in Danny's car.

Next morning, on December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy begins its attack on Pearl Harbor. USS Arizona is completely destroyed when a high-altitude, armor-piercing bomb plummets through the ship's decks and detonates inside the ship's forward ammunition magazine. USS Oklahoma rapidly capsizes after several torpedoes strike her, trapping hundreds of men inside. And the USS West Virginia suffers severe damage.

The next day, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivers his Day of Infamy Speech to the nation and requests the US Congress declare a state of war with the Empire of Japan. The survivors attend a memorial service to honor the numerous dead. Later, Danny and Rafe are both assigned to travel stateside under newly promoted Lt. Colonel Doolittle for a secret mission. Before they leave, Evelyn reveals to Rafe that she is pregnant with Danny's child, and intends to stay with Danny.

Upon their arrival in California, Danny and Rafe are both promoted to Captain and awarded the Silver Star, and volunteer for a secret mission under Doolittle. During the next three months, Rafe, Danny and other pilots train with specially modified B-25 Mitchell bombers. In April, the raiders are sent towards Japan on board USS Hornet. Their mission: Bomb Tokyo, after doing so they will land in allied China. The mission is successful, except at the end Rafe and Danny's plane crashes. They are held at gunpoint by Japanese soldiers. A gunfight ensues, and Danny is mortally wounded shielding Rafe. Rafe tearfully reveals to Danny that Evelyn is pregnant with his child; with Danny's dying breaths he tells Rafe that it is his child now. After the war, Rafe and Evelyn, now married, visit Danny's grave with Danny and Evelyn's son, also named Danny. Rafe then asks his stepson if he would like to go flying, and they fly off into the sunset in the old biplane that his father once had.

Cast

- Ben Affleck as the First Lieutenant (later Captain) Rafe McCawley

- Jesse James as young Rafe McCawley

- Josh Hartnett as First Lieutenant (later Captain) Daniel "Danny" Walker

- Reiley McClendon as young Danny Walker

- Kate Beckinsale as Lieutenant Evelyn Johnson McCawley

- Cuba Gooding Jr. as Petty Officer Second Class Dorie Miller

- Tom Sizemore as Sergeant Earl Sistern

- Jon Voight as President Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Colm Feore as Admiral Husband E. Kimmel

- Mako as Kaigun Taishō (Admiral) Isoroku Yamamoto

- Alec Baldwin as Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Jimmy Doolittle

Supporting characters

- William Lee Scott as First Lieutenant Billy Thompson

- Greg Zola as First Lieutenant Anthony Fusco

- Ewen Bremner as First Lieutenant Red Winkle

- Jaime King as Nurse Betty Bayer

- Catherine Kellner as Nurse Barbara

- Jennifer Garner as Nurse Sandra

- Michael Shannon as First Lieutenant Gooz Wood

- Matt Davis as Joe

- Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa as Kaigun Chūsa (Commander) Minoru Genda

- Dan Aykroyd as Captain Thurman

- Scott Wilson as General George Marshall

- Graham Beckel as Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

- Tom Everett as Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox

- Tomas Arana as Rear-Admiral Frank J. 'Jack' Fletcher

- Peter Firth as Captain Mervyn S. Bennion

- Glenn Morshower as Vice Admiral William F. 'Bull' Halsey Jr.

- Madison Mason as Admiral Raymond A. Spruance

- Sara Rue as Nurse Martha

- Kim Coates as Lieutenant Jack Richards

- Michael Shamus Wiles as Captain Marc Andrew "Pete" Mitscher

- William Fichtner as Mr. Walker (Danny's father)

- Steve Rankin as Mr. McCawley (Rafe's Father)

- Andrew Bryniarski as Joe the Boxer

- Leland Orser as Major Jackson

- Michael Milhoan as Army Commander

- Eric Christian Olsen as gunner to Captain McCawley

- David Kaufman as young nervous doctor

- Tony Curran as Ian

- Brandon Lozano as Baby Danny McCawley (Danny and Evelyn's son)

Production

The proposed budget of $208 million that Bay and Bruckheimer wanted was an area of contention with Disney executives, since a great deal of the budget was to be expended on production aspects. Also controversial was the effort to change the film's rating from R to PG-13. Bay wanted to graphically portray the horrors of war and was not interested in primarily marketing the final product to a teen and young adult audience. Budget fights continued throughout the planning of the film, with Bay "walking" on several occasions. Dick Cook, chairman of Disney at the time, said "I think Pearl Harbor was one of the most difficult shoots of modern history."[4]

In order to recreate the atmosphere of pre-war Pearl Harbor, the producers staged the film in Hawaii and used current naval facilities. Many active duty military members stationed in Hawaii and members of the local population served as extras during the filming. The set at Rosarito Beach in the Mexican state of Baja California was used for scale model work as required. Formerly the set of Titanic (1997), Rosarito was the ideal location to recreate the death throes of the battleships in the Pearl Harbor attack. A large-scale model of the bow section of USS Oklahoma mounted on a gimbal produced an authentic rolling and submerging of the doomed battleship. Production Engineer Nigel Phelps stated that the sequence of the ship rolling out of the water and slapping down would involve one of the "biggest set elements" to be staged. Matched with computer generated imagery, the action had to reflect precision and accuracy throughout.[5] In addition, to simulate the ocean, the film crew used a massive stadium-like "bowl" filled with water. The bowl was built in Honolulu, Hawaii and cost nearly $8 million. Today the bowl is used for scuba training and deep water fishing tournaments.

The vessel most seen in the movie was USS Lexington, representing both USS Hornet and a Japanese carrier. All aircraft take-offs during the movie were filmed on board the Lexington, a museum ship in Corpus Christi, Texas. The aircraft on display were removed for filming and were replaced with film aircraft as well as World War II anti-aircraft turrets. Other ships used in filler scenes included USS Hornet,[6] and USS Constellation during filming for the carrier sequences. Filming was also done on board the museum battleship USS Texas located near Houston, Texas.

Release

Marketing

The first trailer was released in 2000 and was shown alongside screenings of Cast Away and O Brother, Where Art Thou?, with another trailer released in Spring 2001, shown before Pokémon 3: The Movie.

Box office

Pearl Harbor grossed $198,542,554 at the domestic box office and $250,678,391 overseas for a worldwide total of $449,220,945, ahead of Shrek. The film was ranked the sixth highest-earning picture of 2001.[2] It is also the third highest-grossing romantic drama film of all time, as of January 2013, behind Titanic and Ghost.[7]

Critical response

The film received generally negative reviews from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, The film holds an approval rating of 25% based on 190 reviews, with an average rating of 4.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Pearl Harbor tries to be the Titanic of war movies, but it's just a tedious romance filled with laughably bad dialogue. The 40-minute action sequence is spectacular, though."[8] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 44 out of 100 based on 35 reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[9]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film one and a half stars, writing: "Pearl Harbor is a two-hour movie squeezed into three hours, about how, on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese staged a surprise attack on an American love triangle. Its centerpiece is 40 minutes of redundant special effects, surrounded by a love story of stunning banality. The film has been directed without grace, vision, or originality, and although you may walk out quoting lines of dialogue, it will not be because you admire them". Ebert also criticized the liberties the film took with historical facts: "There is no sense of history, strategy or context; according to this movie, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor because America cut off its oil supply, and they were down to an 18-month reserve. Would going to war restore the fuel sources? Did they perhaps also have imperialist designs? Movie doesn't say".[10]

A. O. Scott of the New York Times wrote, "Nearly every line of the script drops from the actors' mouths with the leaden clank of exposition, timed with bad sitcom beats".[11] USA Today gave the film two out of four stars and wrote, "Ships, planes and water combust and collide in Pearl Harbor, but nothing else does in one of the wimpiest wartime romances ever filmed."[12]

In his review for The Washington Post, Desson Howe wrote, "although this Walt Disney movie is based, inspired and even partially informed by a real event referred to as Pearl Harbor, the movie is actually based on the movies Top Gun, Titanic and Saving Private Ryan. Don't get confused."[13] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone magazine wrote, "Affleck, Hartnett and Beckinsale – a British actress without a single worthy line to wrap her credible American accent around – are attractive actors, but they can't animate this moldy romantic triangle".[14] Time magazine's Richard Schickel criticized the love triangle: "It requires a lot of patience for an audience to sit through the dithering. They're nice kids and all that, but they don't exactly claw madly at one another. It's as if they know that someday they're going to be part of "the Greatest Generation" and don't want to offend Tom Brokaw. Besides, megahistory and personal history never integrate here".[15]

Entertainment Weekly was more positive, giving the film a "B−" rating, and Owen Gleiberman praised the Pearl Harbor attack sequence: "Bay's staging is spectacular but also honorable in its scary, hurtling exactitude. ... There are startling point-of-view shots of torpedoes dropping into the water and speeding toward their targets, and though Bay visualizes it all with a minimum of graphic carnage, he invites us to register the terror of the men standing helplessly on deck, the horrifying split-second deliverance as bodies go flying and explosions reduce entire battleships to liquid walls of collapsing metal".[16]

In his review for The New York Observer, Andrew Sarris wrote, "here is the ironic twist in my acceptance of Pearl Harbor – the parts I liked most are the parts before and after the digital destruction of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese carrier planes" and felt that "Pearl Harbor is not so much about World War II as it is about movies about World War II. And what's wrong with that?"[17]

Historical accuracy

Like many historical dramas, Pearl Harbor provoked debate about the artistic license taken by its producers and director. National Geographic Channel produced a documentary called Beyond the Movie: Pearl Harbor[19] detailing some of the ways that "the film's final cut didn't reflect all the attacks' facts, or represent them all accurately".

Many Pearl Harbor survivors dismissed the film as grossly inaccurate and pure Hollywood. In an interview done by Frank Wetta, producer Jerry Bruckheimer was quoted saying: "We tried to be accurate, but it's certainly not meant to be a history lesson".[20] Historian Lawrence Suid's review is particularly detailed as to the major factual misrepresentations of the film and the negative impact they have even on an entertainment film.[21] Some other historical inaccuracies found in the film include the early childhood scenes depicting a Stearman biplane crop duster in 1923; the aircraft was not accurate for the period, as the first commercial crop-dusting company did not begin operation until 1924,[22] and the U.S. Department of Agriculture did not purchase its first cotton-dusting aircraft until April 16, 1926.[23][Note 1]

The inclusion of Affleck's character in the Eagle Squadron is another jarring aspect of the film, since active-duty U.S. airmen were prohibited from joining the squadron, though some American civilians did join the RAF.[24][Note 2] Yet another flaw: Ben Affleck's Spitfire has insignia "RF" – this is an insignia of No. 303 Polish Fighter Squadron. Countless other technical lapses rankled film critics, such as Bay's decision to paint the Japanese Zero fighters green (most of the aircraft in the attack being painted light gray/white), even though he knew that was historically inaccurate, because he liked the way the aircraft looked and because it would help audiences differentiate the "good guys from the bad guys".[25]

One of the film's scenes show Japanese aircraft targeting medical staff and the base's hospital. Although it was damaged in the attack, the Japanese did not deliberately target the U.S. naval hospital and only a single member of its medical staff was killed as he crossed the navy yard to report for duty.[26]

Critics decried the use of fictional replacements for real people, declaring that Pearl Harbor was an "abuse of artistic license".[27] The roles the two male leads have in the attack sequence are analogous to the real historical deeds of U.S. Army Air Forces Second Lieutenants George Welch and Kenneth M. Taylor, who took to the skies in P-40 Warhawk aircraft during the Japanese attack and, together, claimed six Japanese aircraft and a few probables. Taylor, who died in November 2006, called the film adaptation "a piece of trash... over-sensationalized and distorted".[28]

The harshest criticism was aimed at instances in the film where actual historical events were altered for dramatic purposes. For example, Admiral Kimmel did not receive the report that an enemy midget submarine was being attacked until after the bombs began falling, and did not receive the first official notification of the attack until several hours after the attack ended.[29][Note 3]

The scene following the attack on Pearl Harbor, where President Roosevelt demands an immediate retaliatory strike on the soil of Japan, did not happen as portrayed in the film. Admiral Chester Nimitz and General George Marshall are seen denying the possibility of an aerial attack on Japan, but in real life they actually advocated such a strike. Another inconsistency in this scene is when President Roosevelt (who was at this time in his life, stricken and bound to a wheelchair due to Polio) is able to stand up to challenge his staff's distrust in a strike on Japan. This too, never happened in real life.[31] In the film Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto says "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant", a quote which was copied from the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!.[21]

The portrayal of the planning of the Doolittle Raid, the air raid itself, and the raid's aftermath, is considered one of the most historically inaccurate portions of the film. In the film, Jimmy Doolittle and the rest of the Doolittle raiders had to launch from USS Hornet 624 miles off the Japanese coast and after being spotted by a few Japanese patrol boats. In actuality, the Doolittle raiders had to launch 650 miles off the Japanese coast and after being spotted by only one Japanese patrol boat. The aircraft were launched from USS Constellation, standing in for USS Hornet from which the Doolittle Raid was launched. In the film, all of the raiders are depicted as dropping their bombs on Tokyo, with some of the bomb blasts obliterating entire buildings. In actuality, the Doolittle raiders did bomb Tokyo but also targeted three other industrial cities, and the damage inflicted was minimal.[32][33] The film shows the Doolittle raider personnel in China overcoming the Japanese soldiers in a short gun battle with help from a strafing B-25, which never happened in real life.[21] Also, there was no acknowledgement given in the film to the fact that up to 10,000 Chinese civilians were massacred by the Japanese Army in eastern China in retaliation for Chinese assistance of the attacking American aviators, who participated in the Doolittle Raid.

Actor Kim Coates criticized the film[34] for choosing not to portray historically accurate smoking habits and men's hairstyles.

An establishing shot of the United States Department of War building is clearly a shot of the exterior of the U.S. Capitol Building. In 1941, the War Department was housed in the War Department Building in Washington's Foggy Bottom neighborhood (renamed the Harry S Truman Building in 2000) and in the Munitions Building on the National Mall. Neither structure bears any architectural resemblance to the edifice shown in the film.

Anachronisms

Numerous other inconsistencies and anachronisms are present in the film. A sailor has a pack of Marlboro Light cigarettes in his pocket, not introduced until 1972. In the beginning of the movie, a newsreel of 1940 is presented with combat footage in Europe, showing a M-26 Pershing tank fighting in the city of Cologne, which did not happen until March 1945.[35] Earlier, a newsreel of the Battle of Britain in 1940 shows a Focke Wulf 190, which didn't see active service until 1941.

The crop duster in the first scene set in 1923 was not commercially available until the late 1930s.[31]

Actor Michael Milhoan is seen as an army major advising Admiral Kimmel about island air defenses on Oahu. On the morning of the attack, he is seen commanding a radar station. While playing chess he is addressed as "lieutenant" but, in a further inconsistency, is seen wearing the insignia of an army captain.

Four Template:Sclass- destroyers tied abreast of each other at their pier are seen being bombed by the Japanese planes, although this class of ship only entered service with the US Navy in the 1970s. The retired Iowa-class battleship USS Missouri was used to represent USS West Virginia for Dorie Miller's boxing match. West Virginia did not have the modernized World War II-era bridge and masts found on newer U.S. battleships until her reconstruction was finished in 1943, while the Iowa class did not enter service until 1943 onwards. In one shot, the USS Arizona memorial is briefly visible in the background during a scene taking place several months before the attack.

One of Doolittle's trophies in a display case depicts a model of an F-86 Sabre, which was not flown until 1947. Late production models of the B-25J were used instead of the early B-25B. Several shots of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet depicted it as having an angled flight deck, a technology that was not implemented until after the war. While Hornet was portrayed by a World War II-era vessel (USS Lexington), Hornet was a Template:Sclass-, whereas Lexington was a modernized Template:Sclass-.[36] The takeoff sequences for the Doolittle Raid were filmed on USS Constellation, a Template:Sclass- which did not enter service until 1961. As a supercarrier, Constellation has a much longer flight deck than the Yorktown or Essex-class carriers, giving the B-25s a substantially longer (and safer) takeoff run.[37] The Japanese carriers are portrayed more correctly by comparison—, Akagi and Hiryū did have their bridge/conning tower superstructure on the port side rather than the more common starboard configuration. In the movie it was done by maneuvering an Essex-class aircraft carrier backwards to act as Akagi.

Honors and awards

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Sound Editing | George Watters II and Christopher Boyes | Won |

| Best Sound | Greg P. Russell, Peter J. Devlin, and Kevin O'Connell | Nominated | |

| Best Visual Effects | Eric Brevig, John Frazier, Ben Snow, and Ed Hirsh | Nominated | |

| Best Original Song[38] | Diane Warren ("There You'll Be") | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Award | Best Original Song | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Hans Zimmer | Nominated | |

| MTV Movie Award | Best Action Sequence | Attack on Pearl Harbor | Won |

| Golden Raspberry Award | Worst Actor | Ben Affleck | Nominated |

| Worst Screen Couple | Nominated | ||

| Josh Hartnett | Nominated | ||

| Kate Beckinsale | Nominated | ||

| Worst Screenplay | Randall Wallace | Nominated | |

| Worst Picture | Jerry Bruckheimer | Nominated | |

| Michael Bay | Nominated | ||

| Worst Director | Nominated | ||

| Worst Remake or Sequel | Nominated | ||

| World Stunt Taurus Award | Best Aerial Work | Nominated | |

In popular culture

The soundtrack for the 2004 film Team America: World Police contains a song entitled "End of an Act". The song's chorus recounts, "Pearl Harbor sucked, and I miss you" equating the singer's longing to how much "Michael Bay missed the mark when he made Pearl Harbor" which is "an awful lot, girl". The ballad contains other common criticisms of the film, concluding with the rhetorical question "Why does Michael Bay get to keep on making movies?"[39]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

The soundtrack to Pearl Harbor on Hollywood Records was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score (lost to the score of Moulin Rouge!). The original score was composed by Hans Zimmer. The song "There You'll Be" was nominated for the Academy Award and Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song.

- "There You'll Be" – song performed by Faith Hill

- Tennessee – 3:40

- Brothers – 4:04

- ...And Then I Kissed Him – 5:37

- I Will Come Back – 2:54

- Attack – 8:56

- December 7 – 5:08

- War – 5:15

- Heart of a Volunteer – 7:05

- Total Album Time

- 46:21

See also

- Sangam, an earlier 1964 Indian film with a strikingly similar storyline, but with only one friend being a pilot in Sangam, whereas both are pilots in Pearl Harbor.[40]

- Tora! Tora! Tora!, 1970 film about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

- The Chinese Widow, 2017 film about the story described in later half of movie Pearl Harbor in another viewpoint.

References

- ^ The "mischievous" Stearman flight is also unlikely, not only because Stearman did not produce his first aircraft until 1926. Less believably, the aircraft's engine starts, not by having someone swing the propeller, but at the flick of a switch, which would have required the engine being fitted with an electric switch, a very unlikely occurrence.

- ^ The later series cannon armed Spitfires used in the film were also inaccurate, as the RAF had chiefly machine gun-armed Spitfire Mk I/IIs during the Battle of Britain. Limited number of early cannon-armed Spitfires Mk.IB served for brief time with No. 19 Squadron RAF, but these proved to be too unreliable and were soon withdrawn from active service. They also differed slightly from later cannon-armed Spitfire versions, which possessed both autocannons and machine guns, as their armament consisted of single 20 mm British Hispano cannon in each wing only.

- ^ President Roosevelt did not receive the news of the Pearl Harbor attack from an aide or advisor who ran into the room. Rather, he was having lunch with Harry Hopkins, a trusted friend, when he received a phone call from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox.[30]

- Citations

- ^ "PEARL HARBOR (12)". British Board of Film Classification. May 17, 2001. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Pearl Harbor (2001)." Box Office Mojo, 2009. Retrieved: March 25, 2009.

- ^ Cagle, Jess. "Pearl Harbor's Top Gun." Time, May 27, 2001. Retrieved: August 17, 2010.

- ^ Fennessey, Sean (June 27, 2011). "An Oral History of Transformers Director Michael Bay". GQ. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ Sunshine and Felix 2001, p. 135.

- ^ Heines, vienne. "Bringing 'Pearl Harbor' to Corpus Christi." Military.com. Retrieved: January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Romantic Drama Movies at the Box Office." Box Office Mojo: IMDb. Retrieved: January 5, 2013.

- ^ "PEARL HARBOR (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Pearl Harbor Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More at Metacritic" Metacritic. Retrieved: March 23, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "'Pearl Harbor'." Chicago Sun-Times, May 25, 2001. Retrieved: June 25, 2009.

- ^ Scott, A.O. "Pearl Harbor: War Is Hell, but Very Pretty." The New York Times, May 25, 2001. Retrieved: June 25, 2009.

- ^ Clark, Mike. " 'Pearl Harbor' sputters — until Japanese show up." USA Today, June 7, 2001. Retrieved: June 25, 2009.

- ^ Howe, Desson. "Pearl Harbor: Bombs Away." Washington Post, May 26, 2001. Retrieved: June 29, 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter. "Pearl Harbor." Rolling Stone, June 29, 2001. Retrieved: June 29, 2009.

- ^ Schickel, Richard. "Mission: Inconsequential." Time, May 25, 2001. Retrieved: June 25, 2009.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen. "'Jarhead'." Entertainment Weekly, June 1, 2001. Retrieved: June 25, 2009.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (June 10, 2001). "Shrek and Dreck? Well, Not Quite". The New York Observer. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Mitsubishi A6M "Zero-Sen". warbirdsresourcegroup.org. Retrieved: November 20, 2010.

- ^ "Beyond the Movie: Pearl Harbor." National Geographic Society, 2001. Retrieved: March 26, 2009.

- ^ Wetta, Frank; Bay, Michael; Bruckheimer, Jerry; Wallace, Randall (2001). "Pearl Harbor". The Journal of Military History. 65 (4): 1138. doi:10.2307/2677684. JSTOR 2677684.

- ^ a b c Suid, Lawrence. ""Pearl Harbor: Bombed Again"". Archived from the original on August 21, 2001. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Naval History (United States Naval institute), Vol. 15, No. 4, August 2001, p. 20. - ^ Hanson, Dave. "Boeing/Stearman Model 75/PT-13/N2S." daveswarbirds.com. Retrieved: June 22, 2010.

- ^ "Monday, January 1, 1900 – Sunday, December 31, 1939." National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: January 18, 2011.

- ^ ui "Eagle Squadrons", rafmuseum.org.uk. Retrieved: June 22, 2010.

- ^ Cagle 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Clancey, Patrick. "Pearl Harbor Navy Medical Activities." iblio.com. Retrieved: January 16, 2014.

- ^ Padilla, Lyle F.; Castagnaro, Raymond J. (2009). "Medal of Honor Recipients/Nominees Portrayed On Film: Hollywood Abominations, Pearl Harbor (2001)". History, Legend and Myth: Hollywood and the Medal of Honor. Archived from the original on March 17, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia. "Kenneth Taylor; Flew Against Pearl Harbor Raiders." Washington Post, December 12, 2006. Retrieved: March 26, 2009.

- ^ Sullivan 2001, p. 54.

- ^ "Our Heritage in Documents: FDR's "Day of Infamy" Speech: Crafting a Call to Arms." Prologue, Winter 2001, Vol. 33, No. 4. Retrieved: 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b [1]

- ^ Gutthman, Edward. "'Pearl' - Hyped, yet promising / Movie to honor vets, nation's wartime spirit." MyUSA, 7 December 2000.

- ^ Heines, Vivienne. "Bringing 'Pearl Harbor' To Corpus Christi." military.com, 1 August 2000.

- ^ "Full interview: Kim Coates." YouTube. Retrieved: October 4, 2014.

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ "The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners." oscars.org. Retrieved: November 20, 2011.

- ^ "Team America: End of an act lyrics." lyricsbox.com. Retrieved: March 25, 2009.

- ^ 10 Hollywood Movies That Were Inspired By Bollywood, Scoop Whoop, 5 December 2014

- Bibliography

- Arroyo, Ernest. Pearl Harbor. New York: MetroBooks, 2001. ISBN 1-58663-285-X.

- Barker, A.J. Pearl Harbor (Ballantine's Illustrated History of World War II, Battle Book, No. 10). New York: Ballantine Books, 1969. No ISBN.

- Cohen, Stan. East Wind Rain: A Pictorial History of the Pearl Harbor Attack. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1981. ISBN 0-933126-15-8.

- Craig, John S. Peculiar Liaisons: In War, Espionage, and Terrorism in the Twentieth Century. New York: Algora Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-0-87586-331-3.

- Golstein, Donald M., Katherine Dillon and J. Michael Wenger. The Way it Was: Pearl Harbor (The Original Photographs). Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's Inc., 1995. ISBN 1-57488-359-3.

- Kimmel, Husband E. Kimmel's Story. Washington, D.C.: Henry Regnery Co., 1955.

- Prange, Gordon W. At Dawn we Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books, 1981. ISBN 0-14-006455-9.

- Sheehan, Ed. Days of '41: Pearl Harbor Remembered. Honolulu: Kapa Associates, 1977. ISBN 0-915870-01-0.

- Sunshine, Linda and Antonia Felix, eds. Pearl Harbor: The Movie and the Moment. New York: Hyperion, 2001. ISBN 0-7868-6780-9.

- Sullivan, Robert. "What Really Happened." Time, June 4, 2001.

- Thorpe. Briagdier General Elliott R. East Wind Rain: The Intimate Account of an Intelligence Officer in the Pacific, 1939–49. Boston: Gambit Incorporated, 1969. No ISBN.

- Wilmott, H.P. with Tohmatsu Haruo and W. Spencer Johnson. Pearl Harbor. London: Cassell & Co., 2001. ISBN 978-0304358847.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. Aircraft of World War II (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books, 2004. ISBN 1-84013-639-1.

- Wisiniewski, Richard A., ed. Pearl Harbor and the USS Arizona Memorial: A Pictorial History. Honolulu: Pacific Basin Enterprises, 1981, first edition 1977. No ISBN.

External links

- 2001 films

- American films

- English-language films

- Japanese-language films

- 2000s romantic drama films

- 2000s war films

- American aviation films

- American war films

- Battle of Britain films

- Cultural depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Dyslexia in fiction

- Films about shot-down aviators

- Films about the United States Army Air Forces

- Films based on actual events

- Films set in 1923

- Films set in 1941

- Films set in 1942

- Films set in England

- Films set in Hawaii

- Films set in Japan

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films set in Tennessee

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Cambridgeshire

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Gloucestershire

- Films shot in Indiana

- Films shot in Hawaii

- Films shot in Honolulu

- Films shot in Houston

- Films shot in Kent

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Mexico

- Films shot in Nevada

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award

- Pearl Harbor films

- United States Navy in World War II films

- War romance films

- World War II aviation films

- Touchstone Pictures films

- Films scored by Hans Zimmer

- Films directed by Michael Bay

- Films produced by Jerry Bruckheimer

- Films produced by Michael Bay