Perpetual virginity of Mary

The perpetual virginity of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church,[2] and states that Mary, the mother of Jesus, was a virgin ante partum, in partu, et post partum—before, during and after the birth of Christ.[3] In Western Christianity, some Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican and a few other Protestant theologians adhere to the doctrine;[4][5][6][7][8] Eastern Orthodox churches recognize Mary as Aeiparthenos, meaning "ever-virgin".[Notes 1][9] Modern Protestants have largely rejected the doctrine.[10]

The problem facing theologians who want to maintain Mary's perpetual virginity is that the New Testament explicitly affirms her virginity only prior to the conception of Jesus and mentions his brothers, (adelphoi), with Mark and Matthew recording their names and Mark adding unnamed sisters.[11][12] The word adelphos only very rarely means other than a physical or spiritual sibling, and the most natural inference is that Joseph and Mary had other children after the birth of Jesus.[13]

The tradition of the perpetual virginity of Mary first appears in a late 2nd century text called the Gospel of James.[14] It was established as orthodoxy at the Council of Ephesus in 431,[15] the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 gave her the title "Aeiparthenos", meaning Perpetual Virgin, and at the Lateran Synod of 649 Pope Martin I emphasised the threefold character of the perpetual virginity, before, during, and after the birth of Christ.[16]

Origin and history

First appearance: 2nd century

Mary's pre-birth virginity is attested in the Gospel of Matthew and in the Gospel of Luke, but there is no biblical basis for the idea of her perpetual virginity.[17] This first appears in a late 2nd century text called the Protoevangelium of James,[14] in which Mary remains a life-long virgin, Joseph is an old man who marries her without physical desire, and the brothers of Jesus are explained as Joseph's sons by an earlier marriage.[18] The Protoevangelium was widely distributed and seems to have been used to create the stories of Mary which are found in the Quran,[19] but while Muslims agree with Christians that Mary was a virgin at the moment of the conception of Jesus, the idea of her perpetual virginity thereafter is contrary to the Islamic ideal of women as wives and mothers.[20]

The establishment of orthodoxy: 4th century

By the early 4th century the spread of monasticism had promoted celibacy as the ideal state.[21] Athanasius of Alexandria (d.393) declared Mary Aeiparthenos, "ever-virgin", and the liturgy of James the brother of Jesus likewise required a declaration of Mary as ever-virgin.[22] A moral hierarchy was established with marriage occupying the third rank below life-long virginity and widowhood,[23] Eastern theologians generally accepted Mary as Aeiparthenos, but many in the Western church were less convinced.[24] The theologian Helvidius objected to the devaluation of marriage inherent in this view and argued that the two states, of virginity and marriage, were equal.[25] His contemporary Jerome, realising that this would lead to the Mother of God occupying a lower place in heaven than virgins and widows, defended her perpetual virginity in his immensely influential Against Helvidius, issued c.383.[26]

Helvidius soon faded from the scene, but in the 380s and 390s the monk Jovinian followed him in denying Mary's perpetual virginity, writing that if Jesus did not undergo a normal human birth then he himself was not human, which was the teaching of the heresy known as Manicheism.[27] Jerome wrote against Jovinian but failed to mention this aspect of his teaching, and most commentators believe that he did not find it offensive.[27] The only important Christian intellectual to defend Mary's virginity in partu was Ambrose, Archbishop of Milan, who was the chief target of the charge of Manicheism.[28] For Ambrose, both the physical birth of Jesus by Mary and the baptismal birthing of Christians by the Church had to be totally virginal, even in partu, in order to cancel the stain of original sin, of which the pains of labor are the physical sign.[29] It was due to Ambrose that virginitas in partu came to be included consistently in the thinking of subsequent theologians.[30]

Jovinian was condemned as a heretic at a Synod of Milan under Ambrose's presidency in 390 and Mary's perpetual virginity was established as the only orthodox view,[16] although it was not until the Council of Ephesus in 431 that a fully general consensus was established.[15] Further developments were to follow when the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 formally gave her the title "Aeiparthenos", and at the Lateran Synod of 649 Pope Martin I emphasised the threefold character of the perpetual virginity, before, during, and after the birth of Christ.[16]

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation saw a rejection of the sanctity of virginity, and as a result marriage and parenthood were extolled, Mary and Joseph were seen as a normal married couple, and sexual abstinence was no longer regarded as a virtue.[31] It also brought with it the idea of the Bible as the fundamental source of authority regarding God's word (sola scriptura),[32] and the reformers noted that while holy scripture explicitly required belief in the virgin birth, it only permitted the acceptance of perpetual virginity.[33] Despite the lack of clear biblical support for the doctrine,[34] it was supported by Martin Luther (who included reference to it in the Smalcald Articles, a Lutheran confession of faith written in 1537).[35], Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and later Protestant leaders including John Wesley, the co-founder of Methodism.[10][34] This was because these moderate reformers were under pressure from others more radical than themselves who held Jesus to have been no more than a prophet: Mary's perpetual virginity thus became a guarantee of the Incarnation of Christ, despite its shaky scriptural foundations.[36] Notwithstanding the acceptance of the earliest reformers, modern Protestants have largely rejected the perpetual virginity of Mary and it has rarely appeared explicitly in confessions or doctrinal statements.[37]

Doctrine

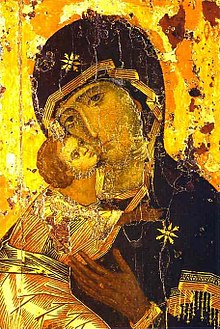

The Second Council of Constantinople recognised Mary as Aeiparthenos, meaning "ever-virgin".[9] It remains axiomatic for the Eastern Orthodox Church that she remained virginal throughout her Earthly life, and Orthodoxy therefore understands the New Testament references to the brothers and sisters of Jesus as signifying his kin, but not the biological children of his mother.[38]

The Latin Church, known more commonly today as the Catholic Church, shared the Council of Constantinople with the theologians of the Greek or Orthodox communion, and therefore shares with them the title Aeiparthenos as accorded to Mary. The Catholic Church has gone further than the Orthodox in making the Perpetual Virginity one of the four Marian dogmas, meaning that it is held to be a truth divinely revealed, the denial of which is heresy.[2] It declares her virginity before, during and after the birth of Jesus,[39] or in the definition formulated by Pope Martin I at the Lateran Council of 649:[40]

The blessed ever-virginal and immaculate Mary conceived, without seed, by the Holy Spirit, and without loss of integrity brought him forth, and after his birth preserved her virginity inviolate.

Thomas Aquinas admitted that reason could not prove this, but argued that it must be accepted because it was "fitting",[41] for as Jesus was the only-begotten son of God, so he should also be the only-begotten son of Mary, as a second and purely human conception would disrespect the sacred state of her holy womb.[42] Symbolically, the perpetual virginity of Mary signifies a new creation and a fresh start in salvation history.[43] It has been stated and argued repeatedly, most recently by the Second Vatican Council:[44]

This union of the mother with the Son in the work of salvation is made manifest from the time of Christ's virginal conception … then also at the birth of Our Lord, who did not diminish his mother's virginal integrity but sanctified it... (Lumen Gentium, No.57)

Arguments and evidence

The major problem facing theologians wishing to maintain Mary's life-long virginity is that the Pauline epistles, the four gospels, and the Acts of the Apostles, all mention the brothers (adelphoi) of Jesus, with Mark and Matthew recording their names and Mark adding unnamed sisters.[11][45][Notes 2] The Gospel of James, followed a century later by Epiphanius, explained that the adelphoi are Joseph's children by an earlier marriage,[46] which is still the view of the Eastern Orthodox Christian churches.[47] Jerome, believing that Joseph, like Mary, must be a life-long virgin,[48] argued that these adelphoi were the sons of "Mary, the mother of James and Joses" (Mk. 15:40), who he identified with the wife of Clopas and sister of the virgin Mary (Jn 19:25).[47] which remains popular in the Western church. A modern proposal considers these adelphoi sons of "Mary, the mother of James and Joses" (not here identified with the Virgin Mary's sister), and Clopas, who according to Hegesippus was Joseph's brother.[47]

Further scriptural difficulties were added by Luke 2:7, which calls Jesus the "first-born" son of Mary,[49] and Matthew 1:25, which adds that Joseph "did not know her until she had brought forth her firstborn son." [50][Notes 3] Helvidius argued that first-born implies later births, and that the word "until" left open the way to sexual relations after the birth; Jerome, replying that even an only son will be a first-born and that "until" did not have the meaning Helvidius construed for it, painted a repulsive word-portrait of Joseph having intercourse with a blood-stained and exhausted Mary immediately after she has given birth - the implication, in his view, of Helvidius's arguments.[26] Opinions on the quality of Jerome's rebuttal range from the view that it was masterful and well-argued to thin, rhetorical and sometimes tasteless.[16]

Two other 4th century Fathers, Gregory of Nyssa and Augustine, advanced a further argument by reading Luke 1:34 as a vow of perpetual virginity on Mary's part; this idea, first introduced in the Protoevangelium of James, has little scholarly support today,[51] but it and the arguments advanced by Jerome and Ambrose were put forward by Pope John Paul II in his catechesis of August 28, 1996, as the four facts supporting the Church's ongoing faith in Mary's perpetual virginity.[52]

See also

- Anglican Marian theology

- Antidicomarians

- Assumption of Mary

- Immaculate Conception

- Lutheran Mariology

- New Eve

- Panachranta (icon)

- Catholic Mariology

- Virgin birth of Jesus

Notes

- ^ Orthodoxy includes the Greek Orthodox Church, itself a communion of churches, plus other communions such as the Russian and Serbian. The theology of all the Eastern Orthodox churches is identical. See the Cambridge Dictionary of Christianity, vol. 2, page895.

- ^ Mark 6:3 names James, Joses, Judas, Simon; Matthew 13:55 has Joseph for Joses, the latter being an abbreviated form of the former, and reverses the order of the last two; Mark 6:3 and Matthew 12:46 refer to unnamed sisters; Luke, John and Acts all mention brothers also. See Bauckham (2015) in bibliography, pages 6-9.

- ^ The phrase "did not know her" is a biblical euphemism for sexual relations (see Gen 4:1). The text neither confirms nor denies the perpetual virginity of Mary, and there is no implication about what happened after Jesus' conception and birth. See Harrington (1991) in bibliography, page 36 footnote 25

References

"Against Heresies 3.21.4". New Advent. c. 180. Retrieved 2021-12-30. To this effect they testify, [saying,] that before Joseph had come together with Mary, while she therefore remained in virginity, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost; Matthew 1:18 and that the angel Gabriel said to her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon you, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow you; therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of you shall be called the Son of God; Luke 1:35 and that the angel said to Joseph in a dream, Now this was done, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by Isaiah the prophet, Behold, a virgin shall be with child. Matthew 1:23

"Against Heresies 3.21.10". New Advent. c. 180. Retrieved 2021-12-30. And as the protoplast himself Adam, had his substance from untilled and as yet virgin soil (for God had not yet sent rain, and man had not tilled the ground Genesis 2:5), and was formed by the hand of God, that is, by the Word of God, for all things were made by Him, John 1:3 and the Lord took dust from the earth and formed man; so did He who is the Word, recapitulating Adam in Himself, rightly receive a birth, enabling Him to gather up Adam [into Himself], from Mary, who was as yet a virgin.

Citations

- ^ Hesemann 2016, p. unpaginated.

- ^ a b Collinge 2012, p. 133.

- ^ Bromiley 1995, p. 269.

- ^ "THE SECOND HELVETIC CONFESSION". www.ccel.org. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- ^ Alexander, Joseph Addison (1863). The Gospel According to Mark. C. Scribner.

- ^ The American Lutheran, Volume 49. American Lutheran Publicity Bureau. 1966. p. 16.

While the perpetual virginity of Mary is held as a pious opinion by many Lutheran confessors, it is not regarded as a binding teaching of the Scriptures.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 11. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1983. p. 562. ISBN 978-0-85229-400-0.

Partly because of these biblical problems, the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary has not been supported as unanimously as has the doctrine of the virginal conceptioon or title mother of God. It achieved dogmatic status, however, at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 and is therefore binding upon Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic believers; in addition, it is maintained by many Anglican, some Lutheran, and a few other Protestant theologians.

- ^ Losch 2008, p. 283.

- ^ a b Fairbairn 2002, p. 100.

- ^ a b Campbell 1996, p. 150.

- ^ a b Maunder 2019, p. 28.

- ^ Parmentier 1999, p. 550.

- ^ Blomberg 2006, p. 387 fn.1.

- ^ a b Lohse 1966, p. 200.

- ^ a b Rahner 1975, p. 896.

- ^ a b c d Polcar 2016, p. 186.

- ^ Boisclair 2007, p. 1465.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 448.

- ^ Bell 2012, p. 110.

- ^ George-Tvrtkovic 2018, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Hunter 2008, p. 412.

- ^ Nathan 2018, p. 229.

- ^ Hunter 2008, p. 412-413.

- ^ Nathan 2018, p. 230.

- ^ Hunter 1999, p. 423-424.

- ^ a b Polcar 2016, p. 185.

- ^ a b Hunter 1993, p. 56-57.

- ^ Hunter 1993, p. 57.

- ^ Hunter 1993, p. 59.

- ^ Rosenberg 2018, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Miller-McLemore 2002, p. 100-101.

- ^ Miller-McLemore 2002, p. 100.

- ^ Pelikan 1971, p. 339.

- ^ a b Breed 1992, p. 237.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 1254.

- ^ MacCulloch 2016, p. 51-52,64.

- ^ Campbell 1996, p. 47,150.

- ^ McGuckin 2010, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Greene-McCreight 2005, p. 485.

- ^ Miravalle 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Dodds 2004, p. 94.

- ^ Miravalle 2006, p. 61-62.

- ^ Fahlbusch 1999, p. 404.

- ^ Miravalle 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Bauckham 2015, p. 6-8.

- ^ Nicklas 2011, p. 2100.

- ^ a b c Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 238.

- ^ Kelly 1975, p. 106.

- ^ Pelikan 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Harrington 1991, p. 36 fn.25.

- ^ Brown 1978, p. 278-279.

- ^ Calkins 2008, p. 308-310.

Bibliography

- Bauckham, Richard (2015). Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781474230476.

- Bell, Richard (2012). The Origin of Islam in Its Christian Environment. Routledge. ISBN 9781136260674.

- Blomberg, Craig (2006). From Pentecost to Patmos: An Introduction to Acts Through Revelation. B&H Publishing. ISBN 9780805432480.

- Boisclair, Regina A. (2007). "Virginity of Mary (Biblical Theology)". In Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. (eds.). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658567.

- Booton, Diane E. (2004). "Variations on a Limbourg Theme". In DuBruck, Edelgard E.; Gusick, Barbara I. (eds.). Fifteenth Century Studies. Vol. 29. Camden House. ISBN 9781571132963.

- Boring, M. Eugene (2006). Mark: A Commentary. Presbyterian Publishing. ISBN 9780664221072.

- Boring, M. Eugene; Craddock, Fred B. (2009). The People's New Testament Commentary. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664235925.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837851.

- Brown, Raymond Edward (1978). Mary in the New Testament. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809121687.

- Bruner, Frederick (2004). Matthew 1-12. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802811189.

- Burkett, Delbert (2019). An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107172784.

- Calkins, Arthur Burton, Msgr. (2008). "Our Lady's Perpetual Virginity". In Miravalle, Mark I. (ed.). Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons. Seat of Wisdom Books. ISBN 9781579183554.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Campbell, Ted (1996). Christian Confessions: A Historical Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256500.

- Collinge, William J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879799.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). "Brethren of the Lord". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Davids, Peter H. (2000). "Brothers of the Lord". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Dodds, Michael J. (2004). "The Teaching of Thomas Aquinas on the Mysteries of the Life of Christ". In Weinandy, Thomas Gerard; Keating, Daniel; Yocum, John (eds.). Aquinas on Doctrine:: A Critical Introduction. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567084118.

- Fairbairn, Donald (2002). Eastern Orthodoxy Through Western Eyes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664224974.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin (1999). "Mariology". In Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824158.

- Fredriksen, Paula (2008). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300164107.

- George-Tvrtkovic, Rita (2018). Christians, Muslims, and Mary: A History. Paulist Press. ISBN 9781587686764.

- Gill, Sean (2004). "Mary". In Hillerbrand, Hans J. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Protestantism. Routledge. ISBN 9781135960285.

- Greene-McCreight, Kathryn (2005). "Mary". In Vanhoozer, Kevin J. (ed.). Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801026942.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658031.

- Hesemann, Michael (2016). Mary of Nazareth: History, Archaeology, Legends. Ignatius Press. ISBN 9781681497372.

- Hunt, Emily J. (2003). Christianity in the Second Century: The Case of Tatian. Routledge. ISBN 9781134409891.

- Hunter, David G. (2008). "Marriage, early Christian". In Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (eds.). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224165.

- Hunter, David G. (1999). "Helvidius". In Fitzgerald, Allan D. (ed.). Augustine Through the Ages. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802838438.

- Hunter, David G. (Spring 1993). "Helvidius, Jovinian, and the Virginity of Mary in Late Fourth-Century Rome". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 1 (1). Johns Hopkins University Press: 47–71. doi:10.1353/earl.0.0147. S2CID 170719507. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- Hurtado, Larry (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802831675.

- Hurtado, Larry (2011). Mark. Baker Books. ISBN 9781441236586.

- Isaak, Jon M. (2011). New Testament Theology: Extending the Table. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781556352935.

- Kelly, John Norman Dividson (1975). Jerome: His Life, Writings, and Controversies. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780715607381.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2013). Born of a Virgin?. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802869258.

- Lohse, Bernhard (1966). A Short History of Christian Doctrine. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451404234.

- Losch, Richard (2008). All the People in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824547.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2004). Reformation: Europe's House Divided 1490-1700. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141926605.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2016). All Things Made New: The Reformation and Its Legacy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190616816.

- Maunder, Chris (2019). "Mary and the Gospel Narratives". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- McGuckin, John Anthony (2010). The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture. Wiley.

- Migliore, Daniel L. (2002). "Woman of Faith". In Gaventa, Beverly Roberts; Rigby, Cynthia L. (eds.). Blessed One: Protestant Perspectives on Mary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224387.

- Miravalle, Mark I. (2006). Introduction to Mary: The Heart of Marian Doctrine and Devotion. Queenship Publishing. ISBN 9781882972067.

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. (2002). ""Pondering All These Things"". In Gaventa, Beverly Roberts; Rigby, Cynthia L. (eds.). Blessed One: Protestant Perspectives on Mary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224387.

- Nathan, Geoffrey (2018). "The Jovinianist Controversy and Mary Aeiparthenos: Questioning Mary's Virginity and the Question of Motherhood". Saeculum. 68 (2): 225–236. doi:10.7788/saec.2018.68.2.225. JSTOR 27638435. S2CID 201446177.

- Nicklas, Tobias (2011). "Traditions About Jesus in Apocryphal Gospels". In Holmén, Tom; Porter, Stanley E. (eds.). Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004163720.

- Parmentier, Martin F.G. (1999). "Mary". In Van Der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (eds.). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (1971). The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. Vol. 4: Reformation of Church and Dogma. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226653778.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (2014). The Melody of Theology. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781625646453.

- Polcar, Philip (2016). "Developments in the Doctrine of Mary's Perpetual Virginity in Antiquity (2nd-7th centuries AD)". In Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (eds.). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History: vol.1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610695664.

- Pomplun, Trent (2008). "Mary". In Buckley, James J.; Bauerschmidt, Frederick C.; Pomplun, Trent (eds.). The Blackwell Companion to Catholicism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470751336.

- Rahner, Karl (1975). Encyclopedia of Theology: A Concise Sacramentum Mundi. A&C Black. ISBN 9780860120063.

- Rampton, Martha (2008). "Mary". In Smith, Bonnie G. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- Rausch, Thomas P. (2016). Systematic Theology: A Roman Catholic Approach. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814683453.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426750083.

- Rosenberg, Michael (2018). Signs of Virginity: Testing Virgins and Making Men in Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190845919.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. (2004). "Jerome, Saint". In Kleinhenz, Christopher (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135948801.

- Schumaker, John F. (1992). Religion and Mental Health. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195361490.

- Stowasser, Barbara Freyer (1996). Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199761838.

- Tilley, Maureen A. (1995). "One Woman's Body: Repression and Expression in the Passio Perpetuae". In Phan, Peter C. (ed.). Ethnicity, Nationality and Religious Experience. University Press of America. ISBN 9780819195241.

- Vuong, Lily C. (2019). The Protevangelium of James. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781532656170.

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry (2005). Christianity and Sexuality in the Early Modern World: Regulating Desire, Reforming Practice. Routledge. ISBN 9781134761210.

- Wheeler-Reed, David (2017). Regulating Sex in the Roman Empire: Ideology, the Bible, and the Early Christians. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300231311.

- Wright, David F. (1992). "Mary". In McKim, Donald K.; Wright, David F. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Reformed Faith. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664218829.

- Zervos, George T. (2019). The Protevangelium of James: Greek Text, English Translation, Critical Introduction. Vol. 1. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780567689757.