Plum Island (Massachusetts)

Location of Plum Island in northeastern Massachusetts. | |

| Etymology | Named for the preponderance of beach plum thickets on the island. |

|---|---|

| Geography | |

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | Barrier island 42°45′20″N 70°47′48″W / 42.75556°N 70.79667°W |

| Administration | |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| • Summer (DST) |

|

Plum Island is a barrier island located off the northeast coast of Massachusetts, north of Cape Ann, in the United States. It is approximately 11 miles (18 km) in length. The island is named for the wild beach plum shrubs that grow on its dunes. It is located in parts of four municipalities in Essex County. From north to south they are the city of Newburyport, and the towns of Newbury, Rowley, and Ipswich.

History

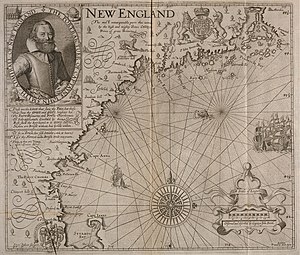

Captain John Smith

Plum Island appears as an unnamed island as early as Captain John Smith's map of New England. Various scholars have speculated on the nature of the earlier accounts of European explorers in the New World, with particular focus on the latter's surveys of the coastlines of Massachusetts, but Smith's account surely identifies Plum Island. He describes a harbor at "Angoam" (elsewhere "Aggawom", the Anglicised Native American name for the native village that preceded Ipswich, Massachusetts, and was destroyed by smallpox) as having "many sands" at its entrance. Before it was an island:

- "On the east is an Ile two or three leagues in length; the one halfe, plain morish grass fit for pasture, with many faire high groves of mulberry trees gardens; and there is also Oaks, Pines and other woods to make this place an excellent habitation, being a good and safe harbor."[1]

"Morish" is now "marsh", and the high gardens of "mulberry" trees must be beach plum, which prefers the crowns of the dunes, although today can be seen on only a few. The map shows an imaginary English town (the insertion of Charles I of England) of the then-future "South Hampton", about where Newbury is. The Hampton suggestions were later put to use, but further north.

The Mason grant

A grant in 1621 by the Plymouth Council for New England, acting under a charter from James I of England (not then reigning) to colonize New England, deeded the land between the "Naumkeag" and Merrimack rivers to Captain John Mason. The island was to be named the Isle of Mason.[2] Mason, then governor of Newfoundland, never acted on the grant. It was later included in a similar grant to the Massachusetts Bay Colony; nevertheless, in 1681 the heirs of John Mason petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts for possession of the grant, now colonized by several communities. After a trial before justices appointed for the purpose, the General Court decided it could not honor the claim, as no one then knew the location of the Naumkeag River, and in any case Mason's grant had been included in another. It did assess a nominal quit-rent fee of a few shillings on land-holders undeniably within the tract; that is, as far south as Ipswich.[3]

Division of the island

Ipswich, Massachusetts, was incorporated as Ipswich in 1634 by settlers of the previous year from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1635 another group from England passed through Ipswich to settle and incorporate Newbury, Massachusetts. In 1639 a third group from England was granted the remaining land between Newbury and Ipswich and incorporated Rowley, Massachusetts. There is no official record of the use of Plum Island until then, although Smith's glowing report had included the marsh grass, an enticing feature for herdsmen. A document of January 2, 1639, survives, however, by which Robert Wallis and Thomas Manning of Ipswich agree to maintain a common herd of 48 hogs on Plum Island starting on April 10 and running to the end of the harvest. One of them was always to be present. Reaction of the other communities was immediate. Newbury filed a petition with the General Court of Massachusetts for ownership of the entire island. The petition was denied on March 13 with the proviso that Ipswich, Rowley and Newbury were allowed use of the island, which became a pasture for hogs, cattle and horses.[4]

In March 1649 Newbury again pressed for title to the island. It argued that "for three of four miles together there is no channel betwixt us and it." At low tide they drove wagons across.[5] These arguments did not prevail; on October 17, 1649, the court finalized its temporary decision, apportioning 2/5 of the island to Newbury, 2/5 to Ipswich and 1/5 to Rowley.[6] There is no hint in the court documents that they ever used a name other than Plum Island. The name is apparently of local origin; the journal of Margaret Smith (1678-9) relates:

- "Leaving on our right hand Plum Island (so-called on account of the rare Plums which do grow upon it), we struck into the open Sea...."[7]

An historian of the region, Joshua Coffin, said of it in 1845:

- "Plum Island, a wild and fantastical sand beach, is thrown up by the joint power of winds and waves into the thousand wanton figures of a snow drift."[8]

Current geography and village

The northern portion of the island is bordered by the mouth of the Merrimack River (in which stands Badgers Rock), the western portion by the Plum Island River in the north (which joins the mouth of the Merrimack to Plum Island Sound), Plum Island Sound in the south (into which empty the Parker, Rowley and Eagle Hill rivers) and the southern portion by the mouth of the Ipswich River (into which the sound empties). The Atlantic Ocean lies to the east. The sound is a tidal estuary.

Now situated in Essex County, Plum Island is divided between four cities and towns: Newburyport, Newbury, Rowley and Ipswich. Developed areas of the island constitute the village of Plum Island, Massachusetts with public beaches, businesses and private residences. The village surrounds a body of water known as "the Basin,"[9] and lies wholly within Newburyport and Newbury, the Newbury portion forming one of three legal precincts of the town. The island's pristine largest section is managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service as the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge. On the mainland opposite, the Massachusetts Audubon Society operates the Joppa Flats Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary.

Plum Island is accessed by one road running from Newburyport to the north of the island on a causeway and drawbridge over the Plum Island River. A charter to build the road between Rolfe's Lane (Ocean Avenue) and the island was granted in 1806 to the Plum Island Turnpike and Bridge Corporation. The road remained a private one until 1905, when the General Court required Essex County to lay it out as a county road, compensating its then owners with a cash settlement.[10]

Plum Island Drive runs along the inland side of the island. In the north it is lined with homes. In the refuge it is paved for about half its distance and is a dusty dirt road for the remainder. Along it are numbered parking lots with boardwalks leading to the beach, overlooks and trails, and facilities for the maintenance of the refuge.

Toward the south is the former site of Camp Sea Haven, a therapeutic camp for those stricken with polio. Visitors are restricted from the levelled site. At the southern end of the road, the tip of the island, is Sandy Point State Reservation, a state park. It is for day use only. At the northern end of the road, the northern tip of the island, is the Plum Island Lighthouse, the only lighthouse remaining on the island. It marks the narrow entrance to the mouth of the Merrimack River. The swift tidal currents through the outlet and through the channel between Ipswich Bay and Ipswich Harbor on the southern end make boating and swimming hazardous.

Touring facilities

Like most coastal communities, Plum Island has historically been a popular vacation destination. Several large hotels operated during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, there are numerous lodging options for tourists, including bed and breakfasts, inns, and rental cottages. In addition, there is a population of year-round residents.

From Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day weekend, the city of Newburyport offers a Friday-Sunday shuttle bus from Plum Island Point to downtown Newburyport and the Newburyport commuter rail station with a connection to Boston. The service is operated by the MVRTA, costs $1.25 for adults paying cash.[11]

Ecology

Great Marsh

Plum Island is a barrier beach sheltering the Plum Island River, Plum Island Sound, and the mouths of the Parker, Rowley, Eagle Hill and Ipswich rivers. The entire area between the islands and the mainland is grassland laced with tidal creeks. At high tide the grassland is entirely submerged, in some places by only a few inches of water. At all other times the extensive stretches of grass appear. The creeks either dry up completely or are small channels within mud flats where shellfish proliferate. The lower stretches of the rivers and Plum Island Sound are thus tidal estuaries receiving the fresh-water flows of the rivers.

The grassland is historically termed "Great Marsh". However, the name also comprises the similar grasslands behind the barrier beaches at Castle Neck (Crane Beach) and Coffins Beach, which shelter the estuaries of the Essex and Annisquam rivers. Not included are the grasslands south of Cape Ann nor the grasslands north of the mouth of the Merrimack River. The entire coast of Massachusetts comprises this type of estuarial terrain, except for the rocky outcrops. Great Marsh has been the focus of a coalition of environmental groups and agencies to protect the marshes between Cape Ann and the Merrimack River from degradation. Historically this coalition continues the work of the founding fathers of Ipswich and other towns in the area, who found it necessary to protect the marsh from overgrazing by means of legislation.

Beach

Plum Island Beach is a gently sloping shelf extending some distance out to sea. As a result of the slope, tidal flow does not reach very far horizontally, while breakers are small and close to shore. Boats can easily be launched from or landed on the beach. The shelf causes strong undertow currents. During severe storms the beach is inundated and the breakers strike the dune line. A number of ships have been wrecked in the shallow waters off Plum Island Beach.

The Labrador Current flows from north to south along the shore, migrating sand in that direction and chilling the coastal waters. Several breakwaters have been constructed along the north coast of the island to protect the beach and impede the process. The migrating sand moves the outlet of the Merrimack River, which has been artificially fixed at its current location.

Vascular plants

On the dunes a fragile cover of beach grass, beach pea and beach heather stabilize the sand. Visitors to the refuge are restricted from the dunes except on boardwalks to protect this cover. Destabilization has been a problem. In 1953 the U.S. Soil Conservation Service planted several thousand black pines, a hardy alpine tree, to help hold the sand.[12]

Stands of black pine, pitch pine and occasional eastern red cedar trees can be found in the depressions between the dunes. There also are thickets of beach plum, from which the island takes its name, as well as bayberry and honeysuckle (the latter being intrusive).[12][13]

Maximum dune elevation is about 50 feet (15 m). In the deeper depressions and more sheltered regions between or next to the higher dunes are vernal pools in which black oak, red maple and black cherry can be found. In the underbrush are cranberry. The ferns, moss and leaf cover there shelter salamanders and spadefoot toads.

The native salt-water marshes between Plum Island and the mainland (Great Marsh) are visible from the western edge of the island. Salt marsh hay which grows there has been harvested for feeding farm animals.

Less visible in "the low marsh" at the margin of the water is smooth cordgrass. Also in the marsh are the sedges, Cyperus and Carex.

In the 1940s and '50s the wildlife service created two freshwater marshes, North and South Pools, from island runoff by diking a section of the marsh contiguous to the island. It serves as a nesting area and stopover for migrating birds. Originally the common cattail dominated the freshwater marshes, but two intrusive plants, the common reed and purple loosestrife, have replaced much of it.

Mammals

The mammals are typical of Massachusetts woodland: the striped skunk, the raccoon, the red fox, the meadow jumping mouse, the white-tailed deer, meadow vole, white-footed mouse and others.

Avians

Plum Island and its surrounding estuaries are a popular destination for birders. Plum Island Sound is on a migratory route for many varieties of birds, as well as being a nesting area for piping plovers. Much of the beach in the National Wildlife Refuge is closed to visitors during the nesting season, which can last most of the warm months.

Several prepared observation posts of birds are usually populated by birders with equipment ranging from simple binoculars to expensive telephoto cameras. Some posts are blinds; others are simply a paved shoulder with a sign. Birds are usually observed in the native salt-water marshes, the artificial fresh-water marshes and the thickets and isolated trees of the refuge.

The birds most commonly observed are listed in the visitor center in the refuge. They are the greater yellowlegs, mallard duck, least sandpiper, great egret, snowy egret, herring gull, great black-backed gull, osprey, Canada goose, tree swallow, gray catbird, killdeer, glossy ibis, red-winged blackbird, northern mockingbird, least tern, piping plover and peregrine falcon.

Beach and dune pests

Greenhead flies

The greatest visible pest to humans is the greenhead fly. Before insect control they swarmed the beach and dunes so thickly as to make human presence there difficult if not impossible from June through September. In recent years[when?] the near elimination of the population with traps has reduced their impact to an occasional bite.

Ticks

The dog tick and the deer tick enter the clothing of their victim from the vegetation and later crawl into the soft tissue, where they attach themselves. Dog ticks are less harmful, except to dogs, from whom they can in sufficient numbers remove a dangerous amount of blood. Deer ticks often carry Lyme disease, which is endemic to the region.

Mosquitoes

The mosquito is a pest everywhere in Massachusetts. Mosquito control has reduced the presence of the pest in the Newbury region. A few cases of eastern equine encephalitis virus, carried by mosquitoes, occur each year.

Poison ivy

Poison ivy is indigenous to all the woodlands of Massachusetts. It especially loves the margins of paths. On Plum Island it grows in every thicket and in mats along the sand. The visitor is cautioned at the visitor center to learn to identify its three shiny leaves.

See also

Notes

- ^ Smith, Captain John (1616). A Description of New England. London: Humfrey Lownes for Robert Clerke. p. 37.

- ^ Felt 1834, p. 36

- ^ Felt 1834, pp. 126–127

- ^ Waters 1918, p. 3

- ^ Waters 1918, p. 4

- ^ Toppan 1905, p. 285

- ^ Whittier 1849, p. 53

- ^ Coffin 1845, p. 7

- ^ "Scientists take a closer look at jetties". The Daily News of Newburyport. 18 June 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Wood 1919, pp. 160–161.

- ^ http://www.cityofnewburyport.com/home/news/newburyport-summer-shuttle-returns-for-weekend-visitors-residents

- ^ a b Hellcat Trail pamphlet

- ^ Bailey, pages 425-426, also describes some vascular plants on the island. The scientific names of some plants have changed since then.

Bibliography

- Bailey, S. Waldo (1915). "The Plum Island Night Herons". The Auk. 32 (1): 424–441. doi:10.2307/4072584.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Coffin, Joshua (1845). A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, from 1635 to 1845. Boston: Samuel G. Drake.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Felt, Joseph Barlow (1834). History of Ipswich, Essex, and Hamilton. Cambridge: Charles Folsom.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Toppan, Robert Noxon (1905). "Edward Rawson". Transactions. 7 (1900–1902). The Colonial Society of Massachusetts: 280–294.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (2006). "Parker River National Wildlife Refuge Guide to the Hellcat Interpretive Trail".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Pamphlet available at the refuge. - Whittier, John Greenleaf (1849). Leaves from Margaret Smith's Journal in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, 1678-9. Ticknor, Reed and Fields.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Waters, Thomas Franklin (1918). "Plum Island: Ipswich, Mass". Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society. XXII. Ipswich Historical Society.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wood, Frederic James (1919). The Turnpikes of New England and Evolution of the Same Through England, Virginia and Maryland. Boston: Marshall Jones Company.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links

- ACEC Program, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection. "ACEC Designations: Great Marsh". Mass.gov (Commonwealth of Massachusetts). Retrieved 7 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Villages in Essex County, Massachusetts

- Articles with inconsistent citation formats

- Islands of Massachusetts

- Massachusetts natural resources

- Bay Circuit Trail

- Islands of Essex County, Massachusetts

- Barrier islands of Massachusetts

- Islands of the North Atlantic Ocean

- Newburyport, Massachusetts

- Newbury, Massachusetts

- Ipswich, Massachusetts

- Rowley, Massachusetts

- Villages in Massachusetts