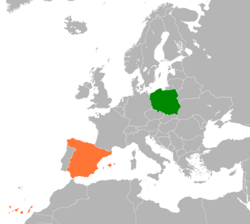

Poland–Spain relations

| |

Poland |

Spain |

|---|---|

Poland–Spain relations (Polish: Stosunki Polska–Hiszpania; Spanish: Relaciones Polonia-España) are cultural and political relations between Poland and Spain. Both nations are members of NATO, the European Union, OECD, OSCE, the Council of Europe and the United Nations. Spain has given full support to Poland's membership in the European Union and NATO.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

First contact between the Kingdoms of Poland and Spain date to Late Middle Ages, where merchants, travelers and Jesuits traveled between both countries. Early Polish diplomats in Spain in the 16th century included Johannes Dantiscus and Piotr Dunin-Wolski.[1][2] While the Polish and Spanish forms of governments evolved in a different direction, the diplomacy of both countries was more likely to support one another than not.[3][4] In 1557, Queen Bona Sforza of Poland made a loan to King Philip II of Spain, most of which was never repaid, despite Polish diplomatic efforts and requests (see Neapolitan sums). In 1639 the two kingdoms signed a military treaty; however, it has not been implemented. Polish writer and translator Andrzej Chryzostom Załuski was a Polish diplomat in Spain in the 1670s. Spain was the only country to protest over the First Partition of Poland, and in 1795, following the final Third Partition of Poland, Spanish diplomat Don Domingo d'Yriarte was one of the last foreign diplomats to vacate his post in Warsaw.[4]

19th century

[edit]During the Peninsular War (1809–1814) in Spain, a number of Polish soldiers fought on the side of Napoleon. The Vistula Legion gained fame at the Battle of Saragossa.[5] The Polish Chevau-léger regiment distinguished itself at the Battle of Somosierra in 1808.[4]

In February 1864, Spanish authorities arrested in Málaga a Polish ship with arms and ammunition, which had been organized by Polish émigré activists in Western Europe to support the ongoing Polish January Uprising in partitioned Poland.[6]

Spain operated two consulates in the territory of partitioned Poland, located in Gdańsk and Warsaw.

20th century

[edit]Poland and Spain re-established diplomatic relations on 30 May 1919, after Poland regained independence in the aftermath of World War I.[7]

In 1936–1939, a number of Polish volunteers participated in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side and were primarily assigned to the Dabrowski Battalion.[8][9] During the Spanish Civil War, the Polish Embassy in Madrid provided shelter and asylum to more than 400 people, Poles and Spaniards, mostly fleeing from Republican forces, but some also from Nationalists.[10] The asylum recipients were men, women and children, people from various social strata with various political views, including survivors of anarchist massacres, e.g. the Cárcel Modelo massacre, merchants, civil servants, lawyers, industrialists, professors, teachers, students, etc.[11] 120 people were successfully evacuated to Marseille, France and Gdynia, Poland, many of whom eventually returned to Spain.[12] Spanish evacuees pointed out the extraordinary hospitality of Poles during their stay in Poland.[13] Honorary Consul of Poland in Valencia Vicente Noguera Bonora was murdered by pro-Republican communist militants just before his planned evacuation from Valencia in August 1936, to which both the Polish government and the Polish Embassy in Madrid responded with an official protest to the then- Republican Spanish authorities.[14][15][16]

During World War II, Spain remained neutral and did not participate in the war directly. Despite pressure from Germany, Spain did not close the Polish embassy, which was thus still able to represent the Polish government-in-exile. The Honorary Consulate of Poland in Barcelona organized temporary accommodation, false documents and transport for Polish civilians and military who fled from France to Spain in 1939–1942 with the intention of reaching the Polish-allied United Kingdom.[17] During the war, some Spanish nationals, alike Poles, were imprisoned by the Germans in the Stalag VIII-C prisoner-of-war camp in Żagań, the Sonnenburg concentration camp in Słońsk, and a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in Osła.[18][19][20]

In 1945, the German occupation of Poland ended and the country's independence was restored, although with a Soviet-installed puppet communist regime. The Polish government-in-exile was officially recognized by Spain as the Polish government until ‘halfway through 1968’ according to Jacek Majchrowski’s study - diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of Poland were established only in 31 January 1977, as the government of the People's Republic of Poland refused to recognize the government of General Francisco Franco.[7] A double tax avoidance agreement was signed between the two countries in Madrid in 1979.[21] After the Autumn of Nations and formation of a new, non-communist Polish government, both countries signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation in 1992.[7] In 1998, both countries signed a Common Polish-Spanish Declaration.[7]

21st century

[edit]Since 2003, irregular bilateral conferences between prime ministers of both nations take place; as of 2012 eight such meetings have taken place.[7][22]

April 12, 2010, was declared a day of national mourning in Spain to commemorate the 96 victims of the Smolensk air disaster, including Polish President Lech Kaczyński and his wife Maria Kaczyńska.[23]

High-level visits

[edit]

Presidential and Prime Ministerial visits from Poland to Spain[24]

- Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki (1990)

- President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (2003)

- Prime Minister Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz (2006)

- President Lech Kaczyński (2008)

- Prime Minister Donald Tusk (2011 and 2013)

- President Bronisław Komorowski (2011)

- Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz (2015)

- Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (2021)

Royal and Prime Ministerial visits from Spain to Poland

- King Juan Carlos I of Spain (1989 and 2001)

- Prime Minister José María Aznar (2004 and 2007)

- Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2009)

- Crown Prince Felipe (2012)

- Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy (2012, 2014, 2016)

- Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez (2018, 2022)

Cultural relations

[edit]

Certain ties in Polish and Spanish cultures can be explained by the fact that Poland and Spain had the highest percentage of petty nobility in Europe (hidalgos, szlachta), which encouraged ties between educated elites, and mutual references.[3][25] Even more importantly, both countries also shared a strong Catholic history, on the frontier of struggles against Islamic conquest (Antemurale Christianitatis, Reconquista).[3] Spain had a significant influence on Polish culture, particularly in literature.[3][4] Spanish works have been translated into Polish and Spain was a setting of some famous Polish works such as The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, and influenced major Polish literary figures, such as Juliusz Słowacki.[26]

In the 21st century both governments promoted their partner's culture at home, with the Polish Year in Spain in 2002 and the Spanish Year in Poland in 2003.[27] There are Cervantes Institutes in Warsaw and Kraków, and a Polish Institute in Madrid. Spain is a popular tourist destination for Poles, with about half a million of Poles visiting Spain each year. The Spanish language is a popular foreign language in Poland.

Polish community in Spain

[edit]Spain has an estimated Polish community of 100,000 people, many who arrived to Spain after World War II and after Poland joined the European Union in 2004.[7]

Trade

[edit]In 2017, trade between Poland Spain totaled €8 billion Euros.[24] Poland's main exports to Spain include: automobile, machinery, pharmaceutical products, electronics and furniture. Spain's main exports to Poland include: automobiles, electrical equipment, electronics and machinery.[28] In 2016, Spanish companies invested €171 million Euros in Poland, becoming the 6th largest foreign direct investor in the country.[24]

Resident diplomatic missions

[edit]

- Poland has an embassy in Madrid, and a consulate-general in Barcelona.[29]

- Spain has an embassy in Warsaw.[30]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Harold B. Segel (1989). Renaissance Culture in Poland: The Rise of Humanism, 1470-1543. Cornell University Press. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0-8014-2286-7. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Adam Kucharski (1 January 2007). Hiszpania i Hiszpanie w relacjach Polaków: wrażenia z podróży i pobytu od XVI do początków XIX w. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Semper. p. 117. ISBN 978-83-7507-022-4. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Marek Jan Chodakiewicz; John Radzilowski (2003). Spanish Carlism and Polish Nationalism: The Borderlands of Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Transaction Publishers. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-9679960-5-9. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Marek Jan Chodakiewicz; John Radzilowski (2003). Spanish Carlism and Polish Nationalism: The Borderlands of Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Transaction Publishers. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-9679960-5-9. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ George Nafziger and Tad J. Kwiatkowski, The Polish Vistula Legion. Napoleon. No. 1 : January 1996

- ^ Zieliński, Stanisław (1913). Bitwy i potyczki 1863-1864. Na podstawie materyałów drukowanych i rękopiśmiennych Muzeum Narodowego w Rapperswilu (in Polish). Rapperswil: Fundusz Wydawniczy Muzeum Narodowego w Rapperswilu. p. 299.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bilateral cooperation". Msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ "Dąbrowszczacy". IPN. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "A Telling "Omission"". Osaarchivum.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ^ Ciechanowski, Jan Stanisław (2000). "Azyl dyplomatyczny w Poselstwie Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w czasie hiszpańskiej wojny domowej (1936–1939)". Przegląd Historyczny (in Polish). No. 91/4. pp. 559–560.

- ^ Ciechanowski, pp. 560–562

- ^ Ciechanowski, pp. 573, 576, 579

- ^ Ciechanowski, p. 580

- ^ Ciechanowski, pp. 552–553

- ^ "Komuniści rozstrzelali honorowego konsula R.P.". Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish). Lwów. 1936-08-23. p. 1.

- ^ "Rozstrzelanie konsula honorowego Rzplitej". Głos Poranny (in Polish). Łódź. 1936-08-22. p. 4.

- ^ "Punkt kontaktowy w Barcelonie". Ośrodek Debaty Międzynarodowej Rzeszów (in Polish). Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Stanek, Piotr; Terpińska-Greszczeszyn, Justyna (2011). "W cieniu "wielkiej ucieczki". Kompleks obozow jenieckich Sagan (1939–1945)". Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny (in Polish). 34. Opole: 128.

- ^ "Słońsk: 73. rocznica zagłady więźniów niemieckiego obozu Sonnenburg". dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Subcamps of KL Gross-Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Umowa między Rządem Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej a Rządem Hiszpanii o unikaniu podwójnego opodatkowania w zakresie podatków od dochodu i majątku, podpisana w Madrycie dnia 15 listopada 1979 r., Dz. U., 1982, vol. 17, No. 127

- ^ "Kontakty polityczne" (in Polish). Madryt.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ^ "Na pogrzeb przyjadą przywódcy z całego świata". Interia.pl (in Polish). 12 April 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Ficha de País: Polonia (in Spanish)

- ^ Norman Davies (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 584. ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Marek Jan Chodakiewicz; John Radzilowski (2003). Spanish Carlism and Polish Nationalism: The Borderlands of Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Transaction Publishers. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-9679960-5-9. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Kultura i nauka" (in Polish). Msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ^ Polonia, Situación de las Relaciones Comerciales con España (in Spanish)

- ^ Embassy of Poland in Madrid

- ^ Embassy of Spain in Warsaw

Further reading

[edit]- Gabriela Makowiecka, Po drogach polsko-hiszpańskich, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków, 1984

External links

[edit]- Bak, Grzegorz, La imagen de España en la literatura polaca del siglo XIX [Recurso electrónico] : (diarios, memorias, libros de viajes y otros testimonios literarios) / Grzegorz Bak ; director, Fernando Presa González, Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2004

- BIBLIOGRAFÍA DE INTERÉS HISPANO-POLACO. En la biblioteca Guillermo Cabrera Infante (Instituto Cervantes de Varsovia)[permanent dead link]

- Beata Wojna, Stosunki polsko-hiszpańskie w Unii Europejskiej, Biuletyn PISM, nr 18 (263), 2005-03-03

- Polonia.es - page of the Polish minority in Spain

- Bilateral cooperation, Polish Embassy in Madrid, Spain