Preta

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

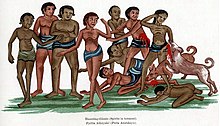

A Burmese depiction of hungry ghosts (pyetta). | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Nocturnal, revenant |

| Other name(s) | Hungry ghost |

| Region | East, South and Southeast Asia |

| Habitat | Hinduism shmashanas or cemetery Buddhism Hungry Ghost Realm |

| Translations of Preta | |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | प्रेत (IAST: preta) |

| Pali | पेत (peta) |

| Burmese | ပြိတ္တာ (MLCTS: peiʔtà) |

| Chinese | 餓鬼 (Pinyin: Èguǐ) |

| Japanese | 餓鬼 (Rōmaji: Gaki) |

| Khmer | ប្រេត (UNGEGN: Praet) |

| Korean | 아귀 (RR: Agui) |

| Lao | ເຜດ (/pʰèːt/) |

| Mon | ပြိုတ် ([[prɒt]]) |

| Mongolian | ᠪᠢᠷᠢᠳ (birid) |

| Shan | ၽဵတ်ႇ ([phet2]) |

| Sinhala | ප්රේත (pretha) |

| Tibetan | ཡི་དྭགས་ (yi dwags) |

| Thai | เปรต (RTGS: pret) |

| Vietnamese | ngạ quỷ, quỷ đói |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Preta (Template:Lang-sa, Template:Lang-bo yi dags), also known as hungry ghost, is the Sanskrit name for a type of supernatural being described in Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Chinese and Vietnamese folk religion as undergoing suffering greater than that of humans, particularly an extreme level of hunger and thirst.[1] They have their origins in Indian religions and have been adopted into East Asian religions via the spread of Buddhism. Preta is often translated into English as "hungry ghost" from the Chinese and Vietnamese adaptations. In early sources such as the Petavatthu, they are much more varied. The descriptions below apply mainly in this narrower context. The development of the concept of the preta started with just thinking that it was the soul and ghost of a person once they died, but later the concept developed into a transient state between death and obtaining karmic reincarnation in accordance with the person's fate.[2] In order to pass into the cycle of karmic reincarnation, the deceased's family must engage in a variety of rituals and offerings to guide the suffering spirit into its next life.[3] If the family does not engage in these funerary rites, which last for one year, the soul could remain suffering as a preta for the rest of eternity.[4]

Pretas are believed to have been false, corrupted, compulsive, deceitful, jealous or greedy people in a previous life. As a result of their karma, they are afflicted with an insatiable hunger for a particular substance or object. Traditionally, this is something repugnant or humiliating, such as cadavers or feces, though in more recent stories, it can be anything, however bizarre.[5] In addition to having insatiable hunger for an aversive item, pretas are said to have disturbing visions.[6] Pretas and human beings occupy the same physical space and while humans looking at a river would see clear water, pretas see the same river flowing with an aversive substance, common examples of such visions include pus and filth.[7]

Through the belief and influence of Hinduism and Buddhism in much of Asia, preta figure prominently in the cultures of India, Sri Lanka, China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Tibet, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

Names

The Sanskrit term प्रेत preta means "departed, deceased, a dead person", from pra-ita, literally "gone forth, departed". In Classical Sanskrit, the term refers to the spirit of any dead person, but especially before the obsequial rites are performed, but also more narrowly to a ghost or evil being.[8]

The Sanskrit term was taken up in Buddhism to describe one of six possible states of rebirth.

The Chinese term egui (餓鬼), literally "starving ghost", is thus not a literal translation of the Sanskrit term.

Description

Pretas are invisible to the human eye, but some believe they can be discerned by humans in certain mental states. They are described as human-like, but with sunken, mummified skin, narrow limbs, enormously distended bellies and long, thin necks. This appearance is a metaphor for their mental situation: they have enormous appetites, signified by their gigantic bellies, but a very limited ability to satisfy those appetites, symbolized by their slender necks.

Pretas are often depicted in Japanese art (particularly that from the Heian period) as emaciated human beings with bulging stomachs and inhumanly small mouths and throats. They are frequently shown licking up spilled water in temples or accompanied by demons representing their personal agony. Otherwise they may be shown as balls of smoke or fire.

Pretas dwell in the waste and desert places of the earth, and vary in situation according to their past karma. Some of them can eat a little, but find it very difficult to find food or drink. Others can find food and drink, but find it very difficult to swallow. Others find that the food they eat seems to burst into flames as they swallow it. Others see something edible or drinkable and desire it but it withers or dries up before their eyes. As a result, they are always hungry.

In addition to hunger, pretas suffer from immoderate heat and cold; they find that even the moon scorches them in the summer, while the sun freezes them in the winter.

The types of suffering are specified into two main types of pretas, those that live collectively, and those that travel through space.[9] Of the former, there are three subtypes, the first being pretas who suffer from external obscurations.[10] These pretas suffer constant hunger, thirst or temperature insensitivity.[11] The second type of pretas are those who suffer from internal obscurations, who have small mouths and large stomachs.[12] Often, their mouths are so small that they cannot eat enough food to fill the large space in their stomachs and thus remain constantly hungry.[13] The last of the three subtypes are pretas that suffer from specific obscurations like creatures who live on and eat their bodies.[14] The other broad category of pretas that travel through time and space are always scared and have a tendency to inflict pain on others.[15]

The sufferings of the pretas often resemble those of the dwellers in hell, and the two types of being are easily confused. The simplest distinction is that beings in hell are confined to their subterranean world, while pretas are free to move about.

Relations between pretas and humans

Pretas are generally seen as little more than nuisances to mortals unless their longing is directed toward something vital, such as blood. However, in some traditions, pretas try to prevent others from satisfying their own desires by means of magic, illusions, or disguises. They can also turn invisible or change their faces to frighten mortals.

Generally, however, pretas are seen as beings to be pitied. Thus, in some Buddhist monasteries, monks leave offerings of food, money, or flowers to them before meals.

In addition, there are many festivals around Asia that commemorate the importance of hungry ghosts or pretas and such festivals exist in Tibetan Buddhist tradition as well as Chinese Taoist tradition.[16] Countries such as China, Tibet, Thailand, Singapore, Japan, and Malaysia engage in hungry ghost festivals, and in China this is usually on the 15th day of the 7th lunar month according to their calendar.[17] Many rituals involve burning symbolized material possessions, such as paper Louis Vuitton bags, thus linking the concept of the preta with the deceased's materialism in their lifetime.[18] Though many pretas or hungry ghosts cling to their material possessions during their human lifetime, some other ghosts represented in the festivals long for their loved ones during their human life.[19] During the festivals, people offer food to the spirits and hope for blessings from their ancestors in return.[20] Thus, the hungry ghost festivals commemorating the pretas are a natural part of some Asian cultures and are not limited to only Hindu or Buddhist belief systems.

Hinduism

In Hinduism pretas are very real beings. They are a form, a body consisting only of vāyu (air) and akaśa (aether), two of the five great elements (classical elements) which constitutes a body on Earth (others being prithvī [earth], jala [water] and agni [fire]). There are other forms as per the karma or "actions" of previous lives where a soul takes birth in humanoid bodies with the absence of one to three elements. In Hinduism an Atma or soul/spirit is bound to take rebirth after death in a body composed of five or more elements. A soul in transient mode is pure and its existence is comparable to that of a deva (god) but in the last form of physical birth. The elements except akaśa as defined is the common constituent throughout the universe and the remaining four are common to the properties of the planets, stars and afterlife places such as the underworld. This is the reason that Pretas cannot eat or drink as the rest of the three elements are missing and no digestion or physical intake is possible for them. [citation needed]

Pretas are crucial elements of Hindu culture, and there are a variety of very specific funerary rituals that the mourning family must engage in to guide the deceased spirit into its next cycle of karmic rebirth.[21] Rice balls, which are said to symbolize the body of the deceased, are offered from the mourning family to the preta[22] whose spirit is often symbolized by a clay mound somewhere in the house.[23] These rice balls are offered in three sets of 16 over one year, which is the amount of time it takes for a preta to complete its transformation into its next phase of life.[24] The rice balls are offered to the preta because in this transient state between cremation and rebirth, the preta is said to undergo intense physical suffering.[25] The three stages are the impure sixteen, the middle sixteen and the highest sixteen that occur over the course of the mourning period.[26] After the physical body of the deceased is cremated, the first six rice balls are offered to ghosts in general, while the next ten are offered specifically to the preta or the spirit of the person who just died.[27] These ten rice balls are said to help the preta form its new body which is now the length of a forearm.[28] During the second stage, sixteen rice balls are offered to the preta, as through each stage of grief it is believed that pretas become even hungrier.[29] At the last and final stage, the preta is said to have a new body, four rice balls are offered and five spiritual leaders of Brahmans are fed so that they can symbolize digesting the sins of the deceased during their life.[30]

While there are specific steps that guide the preta into its new life, during the mourning process, the deceased's family must undergo a series of restrictions to assist the preta and ease its suffering.[31] In Indian cultures, food and digestion is symbolic as it separates the food essential for digestion from the waste products, and thus the same logic is applied to sins of the deceased in their living relatives eating and digesting the symbolic rice balls.[32] In engaging in these rituals, the chief mourner of the deceased individual is the symbolic representation of the spirit or preta.[33] During the period of mourning, the chief mourner can only eat one meal a day for the first eleven days following the death, and also not sleep on a bed, engage in sexual activity or any personal grooming or hygiene practices.[34]

Buddhism

In general in Buddhist tradition, a preta is considered one of the five forms of existence (Gods, humans, animals, ghosts and hell beings) once a person dies and is reborn.[35]

In Japan, preta is translated as gaki (Template:Lang-ja, "hungry ghost"), a borrowing from Middle Chinese ngaH kjwɨjX (Chinese: 餓鬼, "hungry ghost").

Since 657, some Japanese Buddhists have observed a special day in mid-August to remember the gaki. Through such offerings and remembrances (segaki), it is believed that the hungry ghosts may be released from their torment.

In the modern Japanese language, the word gaki is often used to mean spoiled child, or brat.

In Thailand, pret (Template:Lang-th) are hungry ghosts of the Buddhist tradition that have become part of the Thai folklore, but are described as being abnormally tall.[36]

In Sri Lankan culture, like in other Asian cultures, people are reborn as preta (peréthaya) if they desired too much in their life where their large stomachs can never be fulfilled because they have a small mouth.[37]

See also

- Bhavacakra

- Bhoot (ghost)

- Bon Festival

- Buddhist cosmology

- Chöd

- Edimmu

- Ganachakra

- Ghost Festival

- Hungry ghost

- Jikininki

- Kanjirottu Yakshi

- Manes

- Maudgalyayana

- Pitrs

- Segaki

- Tingsha

- Wendigo

References

- ^ Mason, Walter (2010). Destination Saigon: Adventures in Vietnam. ISBN 9781459603059.

- ^ Krishan, Y. (1985). "The Doctrine of Karma and Śrāddhas". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 66 (1/4): 97–115. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41693599.

- ^ Krishan, Y. "THE DOCTRINE": 97–115.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Krishan, Y. "THE DOCTRINE": 97–115.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Garuda Purana 2.7.92-95, 2.22.52-55

- ^ Tzohar, Roy (2017). "Imagine Being a Preta: Early Indian Yogācāra Approaches to Intersubjectivity". Sophia. 56 (2): 337–354. doi:10.1007/s11841-016-0544-y.

- ^ Tzohar, Roy. "Imagine": 337–354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Monier Williams Online Dictionary

- ^ Adrian Cirlea, Josho. "Contemplating the Suffering of Hungry Ghosts (Pretas)". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Cirlea (2017-08-29). "Contemplating the Suffering". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Cirlea (2017-08-29). "Contemplating the Suffering". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Cirlea (2017-08-29). "Contemplating the Suffering". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Cirlea (2017-08-29). "Contemplating the Suffering". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Cirlea (2017-08-29). "Contemplating the Suffering". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Cirlea (2017-08-29). "Contemplating the Suffering". Amida-Ji Retreat Temple Romania.

- ^ Hackley, Rungpaka; Hackley, Chris (2015). "How the Hungry Ghost Mythology Reconciles Materialism and Spirituality in Thai Death Rituals". Qualitative Market Research. 4 (18): 427–441.

- ^ Hackley. "How the Hungry": 337–354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hackley. "How the Hungry": 337–354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hackley. "How the Hungry": 337–354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hackley. "How the Hungry": 337–354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Berger, Peter; Krosen, Justin. Ultimate Ambiguities: Investigating Death and Liminality. Berghahn Books. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Gyan, Prakash (1986). "Reproducing Inequality: Spirit Cults and Labor Relations in Colonial Eastern India". Modern Asian Studies. 2 (20): 209–230. JSTOR 312575.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Parry, Jonathan (1985). "Death and Digestion: The Symbolism of Food and Eating in North Indian Mortuary Rites". Man. 4 (20): 612–630.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Berger; Krosen. Ultimate. pp. 66–68.

- ^ Parry. "Death and Digestion": 612–630.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Parry. "Death and Digestion": 612–630.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Parry. "Death and Digestion": 612–630.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Parry. "Death and Digestion": 612–630.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Tzohar. "Imagine": 337–354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Thai Ghosts (in Thai)[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Failed desires conjure Shyam Selvadurai's the Hungry Ghosts". 2013-05-22.

Further reading

- Firth, Shirley. End of Life: A Hindu View. The Lancet 2005, 366:682-86

- Sharma, H.R. Funeral Pyres Report. Benares Hindu University 2009.

- Garuda Purana. J.L. Shastri/A board of scholars. Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi 1982.

- Garuda Purana. Ernest Wood, S.V. Subrahmanyam, 1911.

- Monier-Williams, Monier M. Sir. A Sanskrit-English dictionary. Delhi, India : Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1990. ISBN 81-208-0069-9.