Reiki

Template:Contains Japanese text

| Part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

| Reiki | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 靈氣 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 灵气 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | linh khí | ||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul | 영기 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja | 靈氣 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Hiragana | れいき | ||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 靈氣 | ||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 霊気 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

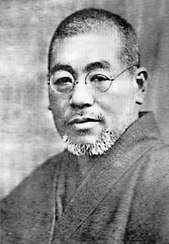

Reiki (/ˈreɪkiː/) is a form of alternative medicine developed in 1922 by Japanese Buddhist Mikao Usui.[1][2] Since its beginning in Japan, Reiki has been adapted across varying cultural traditions. It uses a technique commonly called palm healing or hands-on-healing. Through the use of this technique, practitioners believe that they are transferring "universal energy" through the palms of the practitioner, which they believe encourages healing.

Reiki is considered pseudoscience.[1] It is based on qi ("chi"), which practitioners say is a universal life force, although there is no empirical evidence that such a life force exists.[3] Clinical research has not shown Reiki to be effective as a medical treatment for any medical condition.[3] The American Cancer Society,[4] Cancer Research UK,[5] and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health[6] state that Reiki should not be a replacement for conventional treatment of diseases such as cancer.

Etymology

According to the OED, the English alternative medicine word reiki or Reiki is etymologically from Japanese reiki (霊気) "mysterious atmosphere, miraculous sign" (first recorded in 1001), combining rei "soul, spirit" and ki "vital energy"—the Sino-Japanese reading of Chinese língqì (靈氣) "numinous atmosphere".[7] The earliest recorded English usage dates to 1975.[8]

The Japanese reiki is commonly written as レイキ in katakana syllabary or as 霊気 in shinjitai "new character form" kanji. It compounds the words rei (霊: "spirit, miraculous, divine") and ki (気; qi: "gas, vital energy, breath of life, consciousness").[9] Ki is additionally defined as "... spirits; one's feelings, mood, frame of mind; temperament, temper, disposition, one's nature, character; mind to do something, intention, will; care, attention, precaution". Some reiki translation equivalents from Japanese-English dictionaries are: "feeling of mystery",[10] "an atmosphere (feeling) of mystery",[11] and "an ethereal atmosphere (that prevails in the sacred precincts of a shrine); (feel, sense) a spiritual (divine) presence."[12] Besides the usual Sino-Japanese pronunciation reiki, these kanji 霊気 have an alternate Japanese reading, namely ryōge, meaning "demon; ghost" (especially in spirit possession).[13][14]

Chinese língqì 靈氣 was first recorded in the (ca. 320 BCE) Neiye "Inward Training" section of the Guanzi, describing early Daoist meditation techniques. "That mysterious vital energy within the mind: One moment it arrives, the next it departs. So fine, there is nothing within it; so vast, there is nothing outside it. We lose it because of the harm caused by mental agitation."[15] Modern Standard Chinese língqì is translated by Chinese-English dictionaries as: "(of beautiful mountains) spiritual influence or atmosphere";[16] "1. intelligence; power of understanding; 2. supernatural power or force in fairy tales; miraculous power or force";[17] and "1. spiritual influence (of mountains/etc.); 2. ingeniousness; cleverness".[18]

Origins

According to the inscription on his memorial stone, Usui taught his system of Reiki to over 2000 people during his lifetime.[19][better source needed] While teaching Reiki in Fukuyama (福山市, Fukuyama-shi), Usui suffered a stroke and died on 9 March 1926.[19][better source needed]

Research, critical evaluation, and controversy

Basis and effectiveness

The existence of the proposed mechanism for Reiki – qi or "life force" energy – has not been established.[3] Most research on Reiki is poorly designed and prone to bias. There is no reliable empirical evidence that Reiki is helpful for treating any medical condition,[3][4][5] although some physicians have said it might help promote general wellbeing.[5] In 2011, William T. Jarvis of The National Council Against Health Fraud stated that there "is no evidence that clinical Reiki's effects are due to anything other than suggestion" or the placebo effect.[20]

Reiki's teachings and adherents claim that qi is physiological and can be manipulated to treat a disease or condition. The existence of qi has not been established by medical research.[3] As a result, Reiki is a pseudoscientific theory based on metaphysical concepts.[1]

Scholarly evaluation

Reiki is used as an illustrative example of pseudoscience in scholarly texts and academic journal articles.[1][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] Rhonda McClenton states, "The reality is that Reiki, under the auspices of pseudo-science, has begun the process of becoming institutionalized in settings where people are already very vulnerable."[23] In criticizing the State University of New York for offering a continuing education course on Reiki, Lilienfeld et al. (in Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology) state, "Reiki postulates the existence of a universal energy unknown to science and thus far undetectable surrounding the human body, which practitioners can learn to manipulate using their hands."[31] Ferraresi et al. state, "In spite of its [Reiki] diffusion, the baseline mechanism of action has not been demonstrated..."[32] Wendy Reiboldt states about Reiki, "Neither the forces involved nor the alleged therapeutic benefits have been demonstrated by scientific testing."[33] Several authors have pointed to the vitalistic energy which Reiki is claimed to treat.[34][35][36] Larry Sarner states (in The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience), "Ironically, the only thing that distinguishes Reiki from Therapeutic Touch is that it involves actual touch."[36] Massimo Pigliucci and Maarten Boudry state (in Philosophy of Pseudoscience) that the International Center for Reiki Training "mimic[s] the institutional aspects of science" seeking legitimacy but holds no more promise than an alchemy society.[37] An evidence based guideline published by the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation states, "Reiki therapy should probably not be considered for the treatment of PDN [painful diabetic neuropathy]."[38] Susan Palmer lists Reiki as among the pseudoscientific healing methods used by cults in France to attract members.[39] David Gorski and Steven Novella have commented on the absurdity of clinical testing of implausible treatments.[30]

Issues in the literature

One systematic review of 9 randomized clinical trials conducted by Lee, Pittler, and Ernst (2008) found several issues in the literature on Reiki. First, several of these studies are actually funded by the US National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Second, depending on the tools used to measure depression and anxiety, the results varied and didn’t appear to have much reliability or validity. Furthermore, the scientific community has had issues in replicating the findings of studies that support Reiki. The authors of the review also found issues in reporting methodology in some of the literature, in that often there were parts left out completely or not clearly described. Frequently in these studies, sample sizes are not calculated and adequate allocation and conceal procedures were also not followed. In their review, Lee, Pittler, and Ernst (2008) found that studies without double-blind procedures tended to exaggerate treatment effects as well. Additionally, there was no control for differences in experience of the Reiki administers and they found that even the same healer could produce different outcomes in different studies. None of the studies in the review provided rationale for the treatment duration in such that there is a need for an optimal dosage of Reiki to be established for further research. Another questionable issue with the Reiki research included in this systematic review was that no study reported any adverse effects. It is clear that this area of research requires further studies to be conducted that follow proper scientific method, especially since the main theory on which the therapy is based has never been scientifically proven.[40]

Safety

Safety concerns for Reiki sessions are very low and are akin to those of many CAM practices. Some physicians and health care providers however believe that patients may unadvisedly substitute proven treatments for life-threatening conditions with unproven alternative modalities including Reiki, thus endangering their health.[41][42][43]

Catholic Church concerns

In March 2009, the Committee on Doctrine of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops issued the document Guidelines for Evaluating Reiki as an Alternative Therapy, in which they declared that the practice of reiki was superstition, being neither truly faith healing nor science-based medicine.[44] The guideline concluded that "since Reiki therapy is not compatible with either Christian teaching or scientific evidence, it would be inappropriate for Catholic institutions, such as Catholic health care facilities and retreat centers, or persons representing the Church, such as Catholic chaplains, to promote or to provide support for Reiki therapy."[44] Since this announcement, some Catholic lay people have continued to practice reiki, but it has been removed from many Catholic hospitals and other institutions.[45]

See also

- Energy medicine

- Glossary of alternative medicine

- Laying on of hands

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Shinto

- Vibrational medicine

References

- ^ a b c d Semple, D.; Smyth, R. (2013). "Ch. 1: Psychomythology". Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780199693887.

- ^ Novella, Steven (19 October 2011). "Reiki". Science-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Lee, MS; Pittler, MH; Ernst, E (2008). "Effects of reiki in clinical practice: A systematic review of randomised clinical trials". International Journal of Clinical Practice (Systematic Review). 62 (6): 947–54. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01729.x. PMID 18410352.

In conclusion, the evidence is insufficient to suggest that reiki is an effective treatment for any condition. Therefore the value of reiki remains unproven.

- ^ a b "Reiki". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 15 February 2015 suggested (help) - ^ a b c "Reiki". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Reiki: What You Need To Know". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Reiki". Oxford English Dictionary (OED). 2003. Sino-Japanese readings were historically borrowed from Middle Chinese pronunciations, reconstructed by Baxter-Sagart as lengkhj (靈氣).

- ^ The OED cites The San Mateo Times, 2 May 1975, 32/1, announcing Hawayo Takata's lecture "A Reiki Master's Prediction and Participation in his Own Transition".

- ^ Halpern, Jack (1993) [1990]. New Japanese-English Character Dictionary (新漢英字典) (NTC reprint ed.). Kenkyūsha.

- ^ Spahn, Mark; Hadamidtzy, Wolfgang, eds. (1989). Japanese Character Dictionary With Compound Lookup via Any Kanji. With Fujie-Winter, Kimiko. Tokyo: Nichigai. ISBN 4816908285.

- ^ Nelson, Andrew N.; Haig, John H., eds. (1997). The New Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9780804820363.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editor1link=ignored (|editor-link1=suggested) (help) - ^ Watanabe, Toshiro; Skrzypczak, Edmund R.; Snowden, Paul, eds. (2003). Kenkyūsha's New Japanese-English Dictionary (5th ed.). Tokyo: Kenkyūsha.

- ^ Tetsuji, Morohashi, ed. (1960). Dai Kan-Wa jiten 大漢和辞典. Taishukan.

Akiyasu, Todo, ed. (1978). Kan-Wa Daijiten 漢和大字典. Gakken.

Both dictionaries define ryōge as a mononoke もののけ, meaning "ghost; demon; evil spirit" that possesses people. - ^ Nelson & Haig (1997): Ryō 霊 means "evil spirit who possesses a human".

- ^ Roth, Harold D. (2004). Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism. Columbia University Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780231115650.

Compare translating 靈氣在心 as "The magical qi within the heart"

Eno, R. (2005). "Guanzi: "The Inner Enterprise"" (PDF). Section 18: Moderation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2007.[unreliable source?] - ^ Yutang, Lin, ed. (1972). Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage. Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

- ^ Yuan, Ling, ed. (2002). The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary, Chinese-English Edition. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- ^ DeFrancis, John, ed. (2003). ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary. University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ a b Inscription on Usui's memorial

- ^ Jarvis, William T. "Reiki". National Council Against Health Fraud. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Sokal, Alan D. (2006). "Pseudoscience and Postmodernism: Antagonists or Fellow-Travelers?". In Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.). Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. Psychology Press. pp. 349–. ISBN 9780415305921.

- ^ Bausell, R. Barker (2007). Snake Oil Science: The Truth about Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–7. ISBN 9780199758593.

- ^ a b McClenton, Rhonda (2007). Spirits of the Lesser Gods: A Critical Examination of Reiki and Christ-Centered Healing. Universal Publishers. pp. 187–. ISBN 9781581123449.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (2012). Skulls: An Exploration of Alan Dudley's Curious Collection. Black Dog & Leventhal. pp. 97–. ISBN 9781579129125.

- ^ Donlan, Joseph E. (2009). Ordaining Reality in Brief: The Shortcut to Your Future. Universal Publishers. pp. 63–. ISBN 9781599428925.

- ^ Cortinas-Rovira, S; Alonso-Marcos, F; Pont-Sorribes, C; Escriba-Sales, E (2014). "Science journalists' perceptions and attitudes to pseudoscience in Spain". Public Understanding of Science. 24 (4): 450–65. doi:10.1177/0963662514558991. PMID 25471350.

- ^ Rislove, DC (2006). "Case study of inoperable inventions: Why is the USPTO patenting pseudoscience" (PDF). Wisconsin Law Review: 1275-.

- ^ Thyer, BA; Pignotti, M (2010). "Science and pseudoscience in developmental disabilities: Guidelines for social workers". Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation. 9 (2–3): 110–29. doi:10.1080/1536710X.2010.493480. PMID 20730671.

- ^ Lobato, E; Mendoza, J; Sims, V; Chin, M (2014). "Examining the relationship between conspiracy theories, paranormal beliefs, and pseudoscience acceptance among a university population". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 28 (5): 617–25. doi:10.1002/acp.3042.

- ^ a b Gorski, DH; Novella, SP (2014). "Clinical trials of integrative medicine: Testing whether magic works?". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 20 (9): 473–6. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.06.007. PMID 25150944.

- ^ Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Lynn, Steven Jay; Lohr, Jeffrey M. (2014). Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. Guilford Press. pp. 202–. ISBN 9781462517893.

- ^ Ferraresi, M; Clari, R; Moro, I; Banino, E; Boero, E; Crosio, A; Dayne, R; Rosset, L; Scarpa, A; Serra, E; Surace, A; Testore, A; Colombi, N; Piccoli, B (2013). "Reiki and related therapies in the dialysis ward: An evidence-based and ethical discussion to debate if these complementary and alternative medicines are welcomed or banned". BMC Nephrology. 14 (1): 129-. doi:10.1186/1471-2369-14-129. PMC 3694469. PMID 23799960.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Reiboldt, Wendy (2013). Consumer Survival: An Encyclopedia of Consumer Rights, Safety, and Protection. ABC-CLIO. p. 765. ISBN 9781598849370.

- ^ Canter, Peter H. (2013). "Vitalism and Other Pseudoscience in Alternative Medicine: The Retreat from Science". In Ernst, Edzard (ed.). Healing, Hype or Harm?: A Critical Analysis of Complementary or Alternative Medicine. Andrews UK Limited. pp. 116–. ISBN 9781845407117.

- ^ Smith, Jonathan C. (2011). Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker's Toolkit. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 251–. ISBN 9781444358940.

- ^ a b Sarner, Larry. "Therapeutic Touch". In Shermer, Michael (ed.). The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. pp. 252–. ISBN 9781576076538.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Pigliucci, Massimo; Boudry, Maarten (2013). Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. University of Chicago Press. pp. 178–. ISBN 9780226051826.

- ^ Bril, V; England, J; Franklin, GM; Backonja, M; Cohen, J; Del Toro, D; Feldman, E; Iverson, DJ; Perkins, B; Russell, JW; Zochodne, D (2011). "Evidence-based guideline: Treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: Report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation" (PDF). Neurology. 76 (20): 1758–65. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166ebe. PMC 3100130. PMID 21482920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Palmer, Susan (2011). The New Heretics of France: Minority Religions, la Republique, and the Government-Sponsored "War on Sects". Oxford University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 9780199875993.

- ^ Lee, M.; Pittler, M.; Ernst, E. (2008). "Effects of reiki in clinical practice: A systematic review of randomised clinical trials". International Journal of Clinical Practice. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01729.x.

- ^ "Reiki: Holistic Therapy Treatment Information". Disabled world.com. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) https://nccih.nih.gov/health/reiki/introduction.htm. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Current Issues Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in the United States". US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ a b Committee on Doctrine United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (25 March 2010). "Guidelines for Evaluating Reiki as an Alternative Therapy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lawton, Kim (12 February 2010). "Reiki and the Catholic Church". PBS. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Usui, Mikao (2000). The Original Reiki Handbook of Dr. Mikao Usui: The Traditional Usui Reiki Ryoho Treatment Positions and Numerous Reiki Techniques for Health and Well-being. Lotus Press. ISBN 0-914955-57-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)

External links

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (4 May 2010). "Reiki: An Introduction (NCCAM Backgrounder)". Retrieved 5 May 2010.

Government agency dedicated to exploring complementary and alternative healing practices in the context of rigorous science, training complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) researchers, and disseminating authoritative information to the public and professionals

- Stephen Barrett (4 August 2009). "Reiki Is Nonsense". Retrieved 5 May 2010.

Quackwatch article by Stephen Barrett