Rheumatic fever

| Rheumatic fever | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that occurs following a Streptococcus pyogenes infection, such as streptococcal pharyngitis. Believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain,[1] the illness typically develops two to three weeks after a streptococcal infection. Acute rheumatic fever commonly appears in children between the ages of 6 and 15, with only 20% of first-time attacks occurring in adults.[1] The illness is so named because of its similarity in presentation to rheumatism.[2]

Diagnosis

Modified Jones criteria were first published in 1944 by T. Duckett Jones, MD.[3] They have been periodically revised by the American Heart Association in collaboration with other groups.[4] According to revised Jones criteria, the diagnosis of rheumatic fever can be made when two of the major criteria, or one major criterion plus two minor criteria, are present along with evidence of streptococcal infection: elevated or rising antistreptolysin O titre or DNAase.[1] Exceptions are chorea and indolent carditis, each of which by itself can indicate rheumatic fever.[5][6][7] An April 2013 review article in the Indian Journal of Medical Research stated that echocardiographic and Doppler (E & D) studies, despite some reservations about their utility, have identified a massive burden of rheumatic heart disease, which suggests the inadequacy of the 1992 Jones' criteria. E & D studies have identified subclinical carditis in patients with acute rheumatic fever, as well as in follow-ups of rheumatic heart disease patients who initially presented as having isolated cases of Sydenham's chorea.[8]

Major criteria

- Polyarthritis: A temporary migrating inflammation of the large joints, usually starting in the legs and migrating upwards.

- Carditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis) which can manifest as congestive heart failure with shortness of breath, pericarditis with a rub, or a new heart murmur.

- Subcutaneous nodules: Painless, firm collections of collagen fibers over bones or tendons. They commonly appear on the back of the wrist, the outside elbow, and the front of the knees.

- Erythema marginatum: A long-lasting reddish rash that begins on the trunk or arms as macules, which spread outward and clear in the middle to form rings, which continue to spread and coalesce with other rings, ultimately taking on a snake-like appearance. This rash typically spares the face and is made worse with heat.

- Sydenham's chorea (St. Vitus' dance): A characteristic series of rapid movements without purpose of the face and arms. This can occur very late in the disease for at least three months from onset of infection.

Minor criteria

- Fever of 38.2–38.9 °C (100.8–102.0 °F)

- Arthralgia: Joint pain without swelling (Cannot be included if polyarthritis is present as a major symptom)

- Raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C reactive protein

- Leukocytosis

- ECG showing features of heart block, such as a prolonged PR interval[9][10] (Cannot be included if carditis is present as a major symptom)

- Previous episode of rheumatic fever or inactive heart disease

Other signs and symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Nose bleeds

- Preceding streptococcal infection: recent scarlet fever, raised antistreptolysin O or other streptococcal antibody titre, or positive throat culture.[10]

Pathophysiology

Rheumatic fever is a systemic disease affecting the peri-arteriolar connective tissue and can occur after an untreated Group A Beta hemolytic streptococcal pharyngeal infection. It is believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity. This cross-reactivity is a Type II hypersensitivity reaction and is termed molecular mimicry. Usually, self reactive B cells remain anergic in the periphery without T cell co-stimulation. During a Streptococcus infection, mature antigen presenting cells such as B cells present the bacterial antigen to CD4-T cells which differentiate into helper T2 cells. Helper T2 cells subsequently activate the B cells to become plasma cells and induce the production of antibodies against the cell wall of Streptococcus. However the antibodies may also react against the myocardium and joints,[11] producing the symptoms of rheumatic fever.

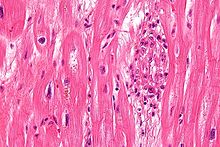

Group A Streptococcus pyogenes has a cell wall composed of branched polymers which sometimes contain M protein that are highly antigenic. The antibodies which the immune system generates against the M protein may cross react with cardiac myofiber protein myosin,[12] heart muscle glycogen and smooth muscle cells of arteries, inducing cytokine release and tissue destruction. However, the only proven cross reaction is with perivascular connective tissue.[citation needed] This inflammation occurs through direct attachment of complement and Fc receptor-mediated recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages. Characteristic Aschoff bodies, composed of swollen eosinophilic collagen surrounded by lymphocytes and macrophages can be seen on light microscopy. The larger macrophages may become Anitschkow cells or Aschoff giant cells. Acute rheumatic valvular lesions may also involve a cell-mediated immunity reaction as these lesions predominantly contain T-helper cells and macrophages.[13]

In acute rheumatic fever, these lesions can be found in any layer of the heart and is hence called pancarditis. The inflammation may cause a serofibrinous pericardial exudate described as "bread-and-butter" pericarditis, which usually resolves without sequelae. Involvement of the endocardium typically results in fibrinoid necrosis and verrucae formation along the lines of closure of the left-sided heart valves. Warty projections arise from the deposition, while subendocardial lesions may induce irregular thickenings called MacCallum plaques.

Rheumatic heart disease

Chronic rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is characterized by repeated inflammation with fibrinous repair. The cardinal anatomic changes of the valve include leaflet thickening, commissural fusion, and shortening and thickening of the tendinous cords.[13] It is caused by an autoimmune reaction to Group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GAS) that results in valvular damage.[14] Fibrosis and scarring of valve leaflets, commissures and cusps leads to abnormalities that can result in valve stenosis or regurgitation.[15] The inflammation caused by rheumatic fever, usually during childhood, is referred to as rheumatic valvulitis. About half of patients with acute rheumatic fever develop inflammation involving valvular endothelium.[16] The majority of morbidity and mortality associated with rheumatic fever is caused by its destructive effects on cardiac valve tissue.[15] The pathogenesis of RHD is complex and not fully understood, but it is known to involve molecular mimicry and genetic predisposition that lead to autoimmune reactions.

Molecular mimicry occurs when epitopes are shared between host antigens and GAS antigens.[17] This causes an autoimmune reaction against native tissues in the heart that are incorrectly recognized as "foreign" due to the cross-reactivity of antibodies generated as a result of epitope sharing. The valvular endothelium is a prominent site of lymphocyte-induced damage. CD4+ T cells are the major effectors of heart tissue autoimmune reactions in RHD.[18] Normally, T cell activation is triggered by the presentation of GAS antigens. In RHD, molecular mimicry results in incorrect T cell activation, and these T lymphocytes can go on to activate B cells, which will begin to produce self-antigen-specific antibodies. This leads to an immune response attack mounted against tissues in the heart that have been misidentified as pathogens. Rheumatic valves display increased expression of VCAM-1, a protein that mediates the adhesion of lymphocytes.[19] Self-antigen-specific antibodies generated via molecular mimicry between human proteins and GAS antigens up-regulate VCAM-1 after binding to the valvular endothelium. This leads to the inflammation and valve scarring observed in rheumatic valvulitis, mainly due to CD4+ T cell infiltration.[19]

While the mechanisms of genetic predisposition remain unclear, a few genetic factors have been found to increase susceptibility to autoimmune reactions in RHD. The dominant contributors are a component of MHC class II molecules, found on lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells, specifically the DR and DQ alleles on human chromosome 6.[20] Certain allele combinations appear to increase RHD autoimmune susceptibility. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II allele DR7 (HLA-DR7) is most often associated with RHD, and its combination with certain DQ alleles is seemingly associated with the development of valvular lesions.[20] The mechanism by which MHC class II molecules increase a host's susceptibility to autoimmune reactions in RHD is unknown, but it is likely related to the role HLA molecules play in presenting antigens to T cell receptors, thus triggering an immune response. Also found on human chromosome 6 is the cytokine TNF-α which is also associated with RHD.[20] High expression levels of TNF-α may exacerbate valvular tissue inflammation, contributing to RHD pathogenesis. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is an inflammatory protein involved in pathogen recognition. Different variants of MBL2 gene regions are associated in RHD. RHD-induced mitral valve stenosis has been associated with MBL2 alleles encoding for high production of MBL.[21] Aortic valve regurgitation in RHD patients has been associated with different MBL2 alleles that encode for low production of MBL.[22] Other genes are also being investigated to better understand the complexity of autoimmune reactions that occur in RHD.

Prevention

Prevention of recurrence is achieved by eradicating the acute infection and prophylaxis with antibiotics. The American Heart Association suggests that dental health be maintained, and that people with a history of bacterial endocarditis, a heart transplant, artificial heart valves, or "some types of congenital heart defects" may wish to consider long-term antibiotic prophylaxis.[23]

Treatment

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

The management of acute rheumatic fever is geared toward the reduction of inflammation with anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin or corticosteroids. Individuals with positive cultures for strep throat should also be treated with antibiotics. Aspirin is the drug of choice and should be given at high doses of 100 mg/kg/day. One should watch for side effects like gastritis and salicylate poisoning. In children and teenagers, the use of aspirin and aspirin-containing products can be associated with Reye's syndrome, a serious and potentially deadly condition. The risks, benefits and alternative treatments must always be considered when administering aspirin and aspirin-containing products in children and teenagers. Ibuprofen for pain and discomfort and corticosteroids for moderate to severe inflammatory reactions manifested by rheumatic fever should be considered in children and teenagers. Steroids are reserved for cases where there is evidence of involvement of heart. The use of steroids may prevent further scarring of tissue and may prevent development of sequelae such as mitral stenosis. Monthly injections of longacting penicillin must be given for a period of five years in patients having one attack of rheumatic fever. If there is evidence of carditis, the length of therapy may be up to 40 years. Another important cornerstone in treating rheumatic fever includes the continual use of low-dose antibiotics (such as penicillin, sulfadiazine, or erythromycin) to prevent recurrence.

Vaccine

No vaccines are currently available to protect against S. pyogenes infection, although there has been research into the development of one. Difficulties in developing a vaccine include the wide variety of strains of S. pyogenes present in the environment and the large amount of time and people that will be needed for appropriate trials for safety and efficacy of the vaccine.[24]

Infection

Patients with positive cultures for Streptococcus pyogenes should be treated with penicillin as long as allergy is not present. This treatment will not alter the course of the acute disease.

The most appropriate treatment stated in the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine for rheumatic fever is benzathine benzylpenicillin.

Inflammation

Patients with significant symptoms may require corticosteroids. Salicylates are useful for pain.

Heart failure

Some patients develop significant carditis which manifests as congestive heart failure. This requires the usual treatment for heart failure: ACE inhibitors, diuretics, beta blockers, and digoxin. Unlike normal heart failure, rheumatic heart failure responds well to corticosteroids.

Epidemiology

Rheumatic fever is common worldwide and responsible for many cases of damaged heart valves. As of 2010 globally it resulted in 345,000 deaths, down from 463,000 in 1990.[26]

In Western countries, it became fairly rare since the 1960s, probably due to widespread use of antibiotics to treat streptococcus infections. While it has been far less common in the United States since the beginning of the 20th century, there have been a few outbreaks since the 1980s. Although the disease seldom occurs, it is serious and has a case-fatality rate of 2–5%.[27]

Rheumatic fever primarily affects children between ages 5 and 17 years and occurs approximately 20 days after strep throat. In up to a third of cases, the underlying strep infection may not have caused any symptoms.

The rate of development of rheumatic fever in individuals with untreated strep infection is estimated to be 3%. The incidence of recurrence with a subsequent untreated infection is substantially greater (about 50%).[28] The rate of development is far lower in individuals who have received antibiotic treatment. Persons who have suffered a case of rheumatic fever have a tendency to develop flare-ups with repeated strep infections.

The recurrence of rheumatic fever is relatively common in the absence of maintenance of low dose antibiotics, especially during the first three to five years after the first episode. Heart complications may be long-term and severe, particularly if valves are involved.

Survivors of rheumatic fever often have to take penicillin to prevent streptococcal infection which could possibly lead to another case of rheumatic fever that could prove fatal.

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2013) |

References

- ^ a b c Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K; Fausto, Nelson; Mitchell, Richard N (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 403–6. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ "rheumatic fever" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Jones, T Duckett (1944). "The diagnosis of rheumatic fever". JAMA. 126 (8): 481–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1944.02850430015005.

- ^ Ferrieri, P; Jones Criteria Working, Group (2002). "Proceedings of the Jones Criteria workshop". Circulation. 106 (19). Jones Criteria Working Group: 2521–3. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000037745.65929.FA. PMID 12417554.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ^ Parrillo, Steven J. "Rheumatic Fever". eMedicine. DO, FACOEP, FACEP. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- ^ "Guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever. Jones Criteria, 1992 update". JAMA. 268 (15). Special Writing Group of the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young of the American Heart Association: 2069–73. 1992. doi:10.1001/jama.268.15.2069. PMID 1404745.

- ^ Saxena, Anita (2000). "Diagnosis of rheumatic fever: Current status of Jones criteria and role of echocardiography". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 67 (4): 283–6. doi:10.1007/BF02758174. PMID 11129913.

- ^ Kumar, RK; Tandon, R (2013). "Rheumatic fever & rheumatic heart disease: The last 50 years". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 137 (4): 643–658. PMC 3724245.

- ^ Aly, Ashraf (2008). "Rheumatic Fever". Core Concepts of Pediatrics. University of Texas. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ a b Ed Boon, Davidson's General Practice of Medicine, 20th edition. P. 617.

- ^ Abbas, Abul K.; Lichtman, Andrew H.; Baker, David L.; et al. (2004). Basic immunology: functions and disorders of the immune system (2 ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2403-3.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last4=(help) - ^ Faé KC, da Silva DD, Oshiro SE; et al. (May 2006). "Mimicry in recognition of cardiac myosin peptides by heart-intralesional T cell clones from rheumatic heart disease". J. Immunol. 176 (9): 5662–70. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5662. PMID 16622036.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaplan, MH; Bolande, R; Rakita, L; Blair, J (1964). "Presence of Bound Immunoglobulins and Complement in the Myocardium in Acute Rheumatic Fever. Association with Cardiac Failure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 271 (13): 637–45. doi:10.1056/NEJM196409242711301. PMID 14170842.

- ^ a b Brice, Edmund A. W; Commerford, Patrick J. (2005). "Rheumatic Fever and Valvular Heart Disease". In Rosendorff, Clive (ed.). Essential Cardiology: Principles and Practice. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press. pp. 545–563. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-918-9_30. ISBN 978-1-59259-918-9.

- ^ Caldas, AM; Terreri, MT; Moises, VA; Silva, CM; Len, CA; Carvalho, AC; Hilário, MO (2008). "What is the true frequency of carditis in acute rheumatic fever? A prospective clinical and Doppler blind study of 56 children with up to 60 months of follow-up evaluation". Pediatric cardiology. 29 (6): 1048–53. doi:10.1007/s00246-008-9242-z. PMID 18825449.

- ^ Guilherme, L; Kalil, J; Cunningham, M (2006). "Molecular mimicry in the autoimmune pathogenesis of rheumatic heart disease". Autoimmunity. 39 (1): 31–9. doi:10.1080/08916930500484674. PMID 16455580.

- ^ Kemeny, E; Grieve, T; Marcus, R; Sareli, P; Zabriskie, JB (1989). "Identification of mononuclear cells and T cell subsets in rheumatic valvulitis". Clinical immunology and immunopathology. 52 (2): 225–37. doi:10.1016/0090-1229(89)90174-8. PMID 2786783.

- ^ a b Roberts, S; Kosanke, S; Terrence Dunn, S; Jankelow, D; Duran, CM; Cunningham, MW (2001). "Pathogenic mechanisms in rheumatic carditis: Focus on valvular endothelium". The Journal of infectious diseases. 183 (3): 507–11. doi:10.1086/318076. PMID 11133385.

- ^ a b c Stanevicha, V; Eglite, J; Sochnevs, A; Gardovska, D; Zavadska, D; Shantere, R (2003). "HLA class II associations with rheumatic heart disease among clinically homogeneous patients in children in Latvia". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 5 (6): R340–R346. doi:10.1186/ar1000. PMC 333411.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Schafranski, MD; Pereira Ferrari, L; Scherner, D; Torres, R; Jensenius, JC; De Messias-Reason, IJ (2008). "High-producing MBL2 genotypes increase the risk of acute and chronic carditis in patients with history of rheumatic fever". Molecular immunology. 45 (14): 3827–31. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.013. PMID 18602696.

- ^ Ramasawmy, R; Spina, GS; Fae, KC; Pereira, AC; Nisihara, R; Messias Reason, IJ; Grinberg, M; Tarasoutchi, F; Kalil, J; Guilherme, L. (2008). "Association of Mannose-Binding Lectin Gene Polymorphism but Not of Mannose-Binding Serine Protease 2 with Chronic Severe Aortic Regurgitation of Rheumatic Etiology". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology : CVI. 15 (6): 932–936. doi:10.1128/CVI.00324-07. PMC 2446618.

- ^ "What About My Child and Rheumatic Fever?" (PDF). American Heart Association. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR) - Group A Streptococcus". World Health Organization. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Lozano, R; Naghavi, M; Foreman, K; Lim, S; Shibuya, K; Aboyans, V; Abraham, J; Adair, T; Aggarwal, R (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first13=missing|last13=(help);|first14=missing|last14=(help);|first15=missing|last15=(help);|first16=missing|last16=(help);|first17=missing|last17=(help);|first18=missing|last18=(help);|first19=missing|last19=(help);|first20=missing|last20=(help);|first21=missing|last21=(help);|first22=missing|last22=(help);|first23=missing|last23=(help);|first24=missing|last24=(help);|first25=missing|last25=(help);|first26=missing|last26=(help);|first27=missing|last27=(help);|first28=missing|last28=(help);|first29=missing|last29=(help);|first30=missing|last30=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ "Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia". NLM/NIHTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Porth, Carol (2007). Essentials of pathophysiology: concepts of altered health states. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7087-4.

External links

- Rheumatic fever information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- Jones major criteria, Mnemonic

- Rheumatic Heart Disease Network