Shōjō

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2016) |

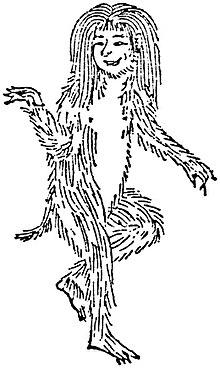

A shōjō (猩々 or 猩猩, heavy drinker or orangutan) is a kind of Japanese sea spirit with red face and hair and a fondness for alcohol.[1][2] The legend is the subject of a Noh play of the same name.[3] There is a Noh mask for this character, as well as a type of Kabuki stage makeup, that bear the name.[3] The Chinese characters are also a Japanese (and Chinese) word for orangutan, and can also be used in Japanese to refer to someone who is particularly fond of alcohol.[3]

Chinese origins

Mythical creatures named "shēng shēng" (狌狌) or "xīng xīng" (猩猩) are mentioned in three passages of the Shan Hai Jing ("The Classic of Mountains and Seas"). Birrell,[4] who translates the creature's name as "live-lively", thus translates the passages:

There is an animal on the mountain which looks like a long-tailed ape, but it has white ears. It crouches as it moves along and it runs like a human. Its name is the live-lively. If you eat it, you'll be a good runner.

— Book One--The Classic of the Southern Mountains--Chapter 1 (p. 3)

Drift Forest is 300 leagues square. It lies east of the land of the live-lively apes. The live-lively apes know the names of humans. These animals are like hogs, but they have a human face.

— Book Ten--The Classic of Regions Within the Seas: The South (p. 135)

There is a green animal with a human face. Its name is live-lively.

— Book Eighteen--The Classic of Regions Within the Seas (p. 192)

The Chinese character Birrell translates as "green" (青, qīng) is also used to refer to colors that in English would be considered "blue," (see Distinguishing blue from green in language) and that illustrator Sun Xiao-qin (孫暁琴, Sūn Xiǎo-qín), in Illustrated Classics: Classic of Mountains and Seas (经典图读山海经, Jīng Diǎn Tú Dú Shān Hǎi Jīng) chose to portray the xīng xīng from this same passage as having blue fur.[5]

Birrell also includes the following note on the creature:

Live-lively (hsing-hsing): A type of ape. The translation of its name reflects the phonetic for ‘live’ (sheng) in the double graph. It is sometimes translated as the orangutan. [Hao Yi-hsing (郝懿行)] notes that its lips taste delicious. He also cites a text of the fourth century AD that gives evidence of their mental powers and their knowledge of human names: ‘In the Yunnan region, the live-lively animals live in mountain valleys. When they see wine and sandals left out, they know exactly who set this trap for them, and, what is more, they know the name of that person's ancestor. They call the name of the person who set the trap and curse them: “Vile rotter! You hoped to trap me!”’

— (p. 236)

In Cryptozoology

In Cryptozoology, the shojo is often referred to as xing-xing and is believed to be a mainland orangutan. Bernard Heuvelmans lists this as an entry in his Annotated Checklist of Apparently Unknown Animals With Which Cryptozoology is Concerned, In CRYPTOZOOLOGY, Vol. 5, 1986,on page 16[citation needed]

Nature, folklore, and popular culture

There is a tale involving the shōjō and white sake. There was a gravely sick man whose dying wish was to drink sake. His son searched for it near Mount Fuji and came across the red shōjō, who were having a drinking party on the beach. The shōjō gave him some sake after listening to his plea. Since the sake revived the dying father, the son went back to the spirit to get more sake each day for five days. A greedy neighbor who also wanted the sake became sick after drinking it. He forced the son to take him to the shōjō to get the good sake. The shōjō explained that as his heart wasn't pure, the sacred sake would not have life-restoring benefits, but instead had poisoned the neighbor. The neighbor repented, and the shōjō gave him some medicine to cure him. The father and the neighbor brewed white sake together.[1]

Several plants and animals have shōjō in their names for their bright, reddish-orange color. Examples include several Japanese maple trees, one of them named shōjō-no-mai or "dancing red-faced monkey" and another named shōjō nomura or "beautiful red-faced monkey."[6] Certain bright reddish-orange dragonflies are named shōjō tonbo (猩猩蜻蛉), meaning "red-faced dragonfly."[7] Other names with shōjō refer to real or fancied connections to sake, like the fly shōjō bae (猩猩蠅) that tends to swarm around open saké.[7]

The Kyōgen-influenced Noh play shōjō or shōjō midare features a shōjō buying sake, getting drunk and dancing ecstatically, then rewarding the sake seller by making his sake vat perpetually refill itself.[8][9] The shōjō from the play have been made into wooden dolls (nara ningyō), they are one of the "most common" wooden dolls derived from Noh plays.[10] Shōjō dolls are used to ward against smallpox.[11]

In Hayao Miyazaki's animated film Princess Mononoke, talking, ape-like creatures struggling to protect the forest from human destruction by planting trees are identified as shōjō.[12][13]

Shōjō appeared in a 2005 Japanese film The Great Yokai War.[14][15]

The Japanese artist Kawanabe Kyōsai, who was also known for his heavy drinking and eccentric behavior,[16] humorously referred to himself as a shōjō.[17]

The March 30, 2012, episode of the television series Supernatural, "Party on, Garth," featured a shōjō. Although, this shōjō appeared to have features more associated with the onryō.

See also

References

- ^ a b Smith, Richard Gordon. (1908). Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan. Chapter XXXVIII, "White Sake," pp. 239-244. London: A. & C. Black. No ISBN. (Reprint edition, Kessinger, Whitefish, MT, no date; http://www.kessinger.net/searchresults-orderthebook.php?ISBN=1428600426; accessed September 18, 2008.) Text and illustrations in color are available at https://books.google.com/books?id=o8QWAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22Richard+Gordon+Smith%22&lr=&as_brr=0#PPA239,M1. (Accessed September 14, 2008).

- ^ Volker, T. (1975, reprint edition). The Animal in Far Eastern Art and Especially in the Art of the Japanese Netsuke, with References to Chinese Origins, Traditions, Legends, and Art. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 141-142. ISBN 90-04-04295-4. These pages, which also include some comments about the origin of the shōjō, can be found here [1]. (Accessed September 18, 2008).

- ^ a b c Shogakukan Daijisen Editorial Staff (1998), Daijisen (大辞泉) (Dictionary of the Japanese language), Revised Edition. Tokyo: Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-501212-4.

- ^ Birrell, Anne, translator (1999). The Classic of Mountains and Seas. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044719-4.

- ^ Wang Gong-qi (王红旗, Wáng Gōng-qí), commentator; Sun Xiao-qin (孫暁琴, Sūn Xiǎo-qín), illustrator (2003). Illustrated Classics: The Classic of Mountains and Seas (经典图读山海经, Jīng Diǎn Tú Dú Shān Hǎi Jīng). Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. ISBN 7-5326-1172-8.

- ^ Vertrees, J.D. and Peter Gregory (2001). Japanese Maples: Momiji and Kaede (Third Edition). Portland, OR: Timber Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-88192-501-2. Here, Vertrees and Gregory translate shōjō as "red-faced monkey" rather than "orangutan."

- ^ a b Dragonflies and flies: http://www6.ocn.ne.jp/~aoidayu/tadaima/200410syoujyou.htm. (Accessed September 18, 2008).

- ^ "NOH & KYOGEN -An Introduction to the World of Noh & Kyogen". .ntj.jac.go.jp. 2002-04-24. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- ^ "Japanese Noh and Kyogen plays: staging dichotomy". Comparative Drama. September 22, 2005.

- ^ Pate, Alan Scott, (2008) Japanese Dolls: The Fascinating World of Ningyō ISBN 978-4-8053-0922-3 page 167

- ^ Pate, Alan Scott, (2008) Japanese Dolls: The Fascinating World of Ningyō ISBN 978-4-8053-0922-3 page 266

- ^ "『もののけ姫』を読み解 (Mononoke Hime o Yomitoku)" [Reading Princess Mononoke]. Comicbox (in Japanese). Tokyo: Fusion Product. 1997. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ "Princess Mononoke" Movie Pamphlet (『もののけ姫』映画パンフレット, Mononoke Hime Eiga Panfuretto) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Toho Company Product Enterprise Division. 1997.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "妖怪大戦争 official site". 2005「妖怪大戦争」製作委員会. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "yokai gallary 猩猩". (株)角川クロスメディア. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ Hiroshi Nara (2007). Inexorable Modernity: Japan's Grappling with Modernity in the Arts. Lexington Books. pp. 34 p. ISBN 0-7391-1842-0.

- ^ Brenda G. Jordan; Victoria Louise Weston; Victoria Weston (2003). Copying the Master and Stealing His Secrets: Talent and Training in Japanese Painting. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 217 p. ISBN 0-8248-2608-6.