Sharing economy

It has been suggested that uberisation be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2016. |

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

| Part of a series on |

| Strategy |

|---|

|

Sharing economy is an umbrella term with a range of meanings, often used to describe economic and social activity involving online transactions. Originally growing out of the open-source community to refer to peer-to-peer based sharing of access to goods and services,[1] the term is now sometimes used in a broader sense to describe any sales transactions that are done via online market places, even ones that are business to consumer (B2C), rather than peer-to-peer. For this reason, the term sharing economy has been criticised as misleading, some arguing that even services that enable peer-to-peer exchange can be primarily profit-driven.[2] However, many commentators assert that the term is still valid as a means of describing a generally more democratized marketplace, even when it's applied to a broader spectrum of services.

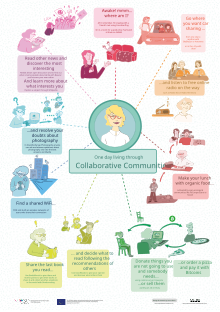

Also known as shareconomy, collaborative consumption or peer economy, a common academic definition of the term refers to a hybrid market model (in between owning and gift giving) of peer-to-peer exchange. Such transactions are often facilitated via community-based online services.[1][3]

The sharing economy can take a variety of forms, including using information technology to provide individuals with information that enables the optimization of resources[1][4] through the mutualization of excess capacity in goods and services.[1][4][5][6] A common premise is that when information about goods is shared (typically via an online marketplace), the value of those goods may increase for the business, for individuals, for the community and for society in general.[7]

Collaborative consumption as a phenomenon is a class of economic arrangements in which participants mutualize access to products or services, rather than having individual ownership.[1][5] The phenomenon stems from an increasing consumer desire to be in control of their consumption instead of "passive 'victims' of hyperconsumption".[8] The consumer peer-to-peer rental market is valued at $26bn (£15bn), with new services and platforms emerging frequently.[9]

The collaborative consumption model is used in online marketplaces such as eBay as well as emerging sectors such as social lending, peer-to-peer accommodation, peer-to-peer travel experiences,[10] peer-to-peer task assignments or travel advising, carsharing or commute-bus sharing.[11]

The Harvard Business Review, the Financial Times and many others have argued that "sharing economy" is a misnomer. Harvard Business Review suggested the correct word for the sharing economy in the broad sense of the term is "access economy". The authors say, "When "sharing" is market-mediated—when a company is an intermediary between consumers who don't know each other—it is no longer sharing at all. Rather, consumers are paying to access someone else's goods or services."[12]

Scope

According to sharing economy expert Alex Stephany, it is a mystery as to who first used the term sharing economy, which has left the term "without a guardian and vulnerable to loose definitions."[13]

A variety of definitions exist. "The people who share" is one of the broadest definitions, which encompasses the on-demand economy, the gig economy, social media, and a great deal else.[14] Academic definitions tend to be narrower, limiting the sharing economy to only peer-to-peer transactions, and sometimes further limiting the definition to only peer to peer transactions that relate to the temporary exchange of physical goods.[15] Another set of narrow definitions used by free culture activists, members of the co-operative movement and similar, excludes for-profit companies from the sharing economy, even if they facilitate just peer to peer transactions. Sometimes called the "real" or "true" sharing economy, organisations that operate within such definitions are mostly small and localist, run by volunteers on a cooperative basis, though sometimes also by governments and municipal authorities. They can include some organisations that operate without online transactions, such as bike kitchens. The "true" sharing economy does include some large internationally available web sites however, such as Freecycle.[15][16][17]

The term sharing economy has been widely used since about 2010, yet according to a Pew survey taken in winter 2015, only 27% of Americans had heard of the term.[18]

Survey respondents who had heard of the term had divergent views on what it meant, with many thinking it concerned "sharing" in the traditional sense of the term.[18] In 2010 and 2011, many people involved with the sharing economy did indeed consider it to be about sharing in the traditional sense. A commonly used example at the time was the idea of sharing a power drill —a tool that many consumers might use for only a few minutes in their lifetime. Advocates said it made sense for regular consumers not to buy their own power drill, but to borrow from others instead, and that this borrowing could be facilitated by online platforms. Several startups companies were launched to help people share drills and similar goods along these lines. Yet looking back from 2015, it was clear that consumers had generally not been interested in such temporary exchanges, leading to the failure of many startups which aimed to facilitate traditional sharing. While some successful platforms such as Airbnb can be described as involving the sharing of a resource, as of 2016 the term sharing economy has been widely criticised as being misleading.[19][20]

The scope of the sharing economy has been a subject of academic debate. Depending on the criteria used, some platforms would be included within the sharing economy, but not others. For example, going by whether companies self-describe as being part of the sharing economy, TaskRabbit would be included, but not mechanical turk.[21]

Commercial implementations[22] encompass a wide range of structures including mostly for-profit, and, to a lesser extent, co-operative structures.[23] The sharing economy provides expanded access to products, services and talent beyond one-to-one or singular ownership, which is sometimes referred to as "disownership".[24] individuals actively participate as users, providers, lenders or borrowers in varied and evolving peer-to-peer exchange schemes which are often web-mediated.[25]

History

Several key macro developments led to the (re-)emergence of mutualization in consumption. The "sharing economy" results from several deep-seated technological, economic, political, and societal changes:[26]

- Technological: The Web transformed consumers' relationship to objects

- Economic: Austerity and crises, decline of stable and full-time employment as well as of purchasing power

- Political: Withering of the State and its increased adjustment to the market ethos

- Social: Consumers view consumption as a central project in their lives

The term "sharing economy" began to appear in the early 2000s, as new business structures emerged due to the Great Recession, enabling social technologies, and an increasing sense of urgency around global population growth and resource depletion. Professor Lawrence Lessig was possibly first to use the term in 2008, though others claim the origin of the term is unknown.[13][27]

The phenomena of the sharing economy certainly emerged much earlier than 2008 however, even in the sense of exchange co-ordinated by online platforms. One inspiration was the tragedy of the commons, which refers to the idea that when we all act solely in our self-interest, we deplete the shared resources we need for our own quality of life. The Harvard law professor, Yochai Benkler, one of the earliest proponents of open source software, posited that network technology could mitigate this issue through what he called 'commons-based peer production', a concept first articulated in 2002.[28] Benkler then extended that analysis to "shareable goods" in Sharing Nicely: On Shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production.[29]

The term "collaborative consumption" was coined by Marcus Felson and Joe L. Spaeth in their paper "Community Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A routine activity approach" published in 1978 in the American Behavioral Scientist.[30]

In 2011, collaborative consumption was named one of TIME Magazine's 10 ideas that will change the world.[31]

Developments since 2015

The UK Government in its 2015 Budget set out objectives to improve economic growth including to make Britain the "...best place in the world to start, invest in, and grow a business, including through a package of measures to help unlock the potential of the sharing economy...".[32]: 4

Also in 2015, The Business of Sharing by Alex Stephany, CEO of JustPark, was published by Palgrave Macmillan.[33] The book features interviews with the high-profile entrepreneurs such as Martin Varsavsky and venture capitalists such as Fred Wilson.

Size and growth

The rapid growth of the sharing economy has been frequently remarked on.[12] Yet according to a June 2016 report by the United States Department of Commerce, quantitative research on size and growth remains sparse. Such growth estimates as there are can be challenging to evaluate due to different and sometimes unspecified definitions about what sort of activity counts as sharing economy transactions.[16]

The June 2016 report summarised currently available research. This included a 2014 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, which looked at five components of the sharing economy: travel, car sharing, finance, staffing and streaming. It found that global spending in these sectors totalled about $15 billion in 2014, which was only about 5% of the total spending in those areas. The report also forecasts a possible increase of "sharing economy" spending in these areas to $335 billion by 2025, which would be about 50% of the total spending in said five areas.[16][16][34]

Types of collaborative consumption

Product-service systems

Product-service systems refer to commercial peer-to-peer mutualization systems (CPMS), allowing consumers to engage in monetized exchanges through peer-to-peer-based for temporary access to goods.[35] Goods that are privately owned can be shared or rented out via peer-to-peer marketplaces.[36] (E.g. BMW's "Drive Now" is a car sharing service that offers an alternative to owning a car. Users can access a car when and where they need them and pay for their usage by the minute.[37])

Redistribution markets

A system of collaborative consumption is based on used or pre-owned goods being passed on from someone who does not want them to someone who does want them. This is another alternative to the more common 'reduce, reuse, recycle, repair' methods of dealing with waste. In some markets, the goods may be free, as on Freecycle and Kashless. In others, the goods are swapped (as on Swap.com) or sold for cash (as on eBay, craigslist, and uSell). There are a growing number of specialist marketplaces for preowned fashion items, including Copious, Vestiaire Collective, BuyMyWardrobe and Grand Circle. Additional forms of redistribution markets include ReHome (a free pet redistribution service by PetBridge.org).[36]

Collaborative lifestyles

Collaborative lifestyles refer to commercial peer-to-peer mutualization systems (CPMS), allowing consumers to engage in monetized exchanges through peer-to-peer-based for services or access to resources such as money or skills.[35] These systems are based on people with similar needs or interests banding together to mutualize and exchange less-tangible assets such as time, space, skills, and money. An example would be Taskrabbit, which match users that need tasks done with "runners" who earn money by helping them complete their to-do lists. The growth of mobile technology provides a platform to enable location-based GPS technology and to also provide real-time sharing.[38]

Crowdfunding platforms

These models also use a two-sided marketplace to enable individuals to contribute funds to entrepreneurs, artists, civic programs and projects.[39]

Transparent and open data

Many state, local and federal governments[40] are engaged in Open Data initiatives and projects such as data.gov[41] and the London Data Store.[42] The theory of open or 'transparent' access to information enables greater innovation,[43] and makes for more efficient use of products and services, and thus supporting resilient communities.[44]

Trust

The Sharing Economy relies on the will of the users to share, but in order to make an exchange, users have to be trustworthy and trust each other. Sharing economy organizations say they are committed to building and validating trusted relationships between members of their community, including producers, suppliers, customers or participants.[45] Beyond trusting others (i.e., the peers), the users of a Sharing Economy platform also have to trust the platform itself as well as the product at hand.[46]

Unused value is wasted value

Unused value refers to the time that products, services and talents lay idle. This idle time is wasted value that mesh models businesses and organizations utilize. The classic example is that the average car is unused 92% of the time.[47] This wasted value has created a significant opportunity for share economy car solutions. There is also significant unused value in "wasted time" as articulated by Clay Shirky in his analysis of power of "crowds" connected by information technology. Many of us have unused capacity in the course of our day. With social media and information technology, we can easily donate small slivers of time to take care of simple tasks others need doing. Examples of these crowd sourced solutions[48] include the for-profit Amazon Mechanical Turk and the non-profit Ushahidi.

Waste as food

Waste is commonly considered as something that is no longer wanted and needs to be discarded. The challenge with this point of view is that much of what we define as waste still has value that, with proper design and distribution, can safely serve as "nutrients" for follow-on processes, unlocking new levels of value in increasingly scarce and expensive resources. One example is "heirloom design"[49] as articulated by physicist and inventor Saul Griffith.[50]

Driving forces

The driving forces behind the rise of sharing economy organizations and businesses include:

- Information Technology and Social Media: A host of enabling technologies has reached the mainstream, making it easy for networks of people and organizations to transact directly. These include open data,[51] the ubiquity and low-cost of mobile phones,[52] and social media.[53] These technologies dramatically reduce the friction of share-based business and organizational models.

- Increasing Volatility in Cost of Natural Resources: Rising prosperity across the developing world coupled with population growth is putting greater strain on natural resources and has caused a spike in costs and market volatility. This has been increasing pressure on traditional manufacturers to seek design, production and distribution alternatives that will stabilize costs and smooth projected expenditures. In this context, the circular economy approach has been gaining interest among many global corporate actors. While a handful of pioneering companies are leading the way, wider adoption will rely on mesh economy skills such as the collection and sharing of data, the spread of best practices, and increased collaboration.[54]

- Forbes estimates the revenue flowing through the shared economy will surpass $3.5 billion in 2013 with growth exceeding 25%.[55]

Benefits of a sharing economy

This section contains promotional content. (May 2016) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |

By sharing transportation and assets the benefits of a sharing economy are said[by whom?] to include the following:

- Reducing negative environmental impact by reducing the amount of good needing to be produced which cuts down on industry pollution (such as reducing the carbon footprint and consumption of resources)[56][57][58]

- Stronger communities[dubious – discuss][57]

- Saving costs by borrowing and recycling items[57]

- Providing people with access to goods who can't afford buying them[dubious – discuss][59][unreliable source?] or have no interest in long-term usage

- Increased independence, flexibility and self-reliance by decentralization, the abolition of certain[which?] entry-barriers and self-organization[60][unreliable source?]

- Increased participatory democracy[dubious – discuss][58]

- Accelerating sustainable consumption and production patterns in cities around the globe[clarification needed][61]

- Increased quality of service through rating system provided by companies involved in the sharing economy[62]

- Increased flexibility of work hours and wages for independent contractors of the sharing economy[63]

Researcher Christopher Koopman, an author of a[which?] study by George Mason University economists, said the sharing economy "allows people to take idle capital and turn them into revenue sources." He has stated, "People are taking spare bedroom[s], cars, tools they are not using and becoming their own entrepreneurs."[64] Arun Sundararajan, a New York University economist who studies the sharing economy, told a January congressional hearing that "this transition will have a positive impact on economic growth and welfare, by stimulating new consumption, by raising productivity, and by catalyzing individual innovation and entrepreneurship".[65][unreliable source?]

An independent data study conducted by BUSBUD compared the average price of hotel rooms with the average price of Airbnb listings in thirteen major cities in the United States. The research concluded that in nine of the thirteen cities, Airbnb rates were lower than hotel rates by an average price of $34.56.[66] A further study conducted by BUSBUD compared the average hotel rate with the average Airbnb rate in eight major European cities. The research concluded that that the Airbnb rates were lower than the hotel rates in six of the eight cities by a factor of $72.[66]

Transport

Using a personal car to transport passengers or deliveries requires payment, or sufferance, of costs for fees deducted by the dispatching company, fuel, wear and tear, depreciation, interest, taxes, and adequate insurance. The driver is typically not paid for driving to an area where fares might be found in the volume necessary for high earnings, or driving to the location of a pickup or returning from a drop-off point.[67] Mobile apps have been written that help a driver be aware of and manage such costs has been introduced.[68]

Uber, Airbnb, and other companies have had drastic effects on infrastructures such a road congestion and housing. Major cities such as San Francisco and New York City have become even more congested due to ride sharing. According to transportation analyst Charles Komanoff, "Uber-caused congestion has reduced traffic speeds in downtown Manhattan by around 8 percent".[69]

The New York Times wrote that there was a recent corporate decision by Uber which aimed at lowering its fare rates by 15% in over 100 cities in the United States.[70] This decision caused many Uber employee drivers to assemble and express their disagreement with the recent pay cut. Uber has made a statement claiming that "when it cut prices previously, the amount of time drivers spent waiting for fares fell, meaning drivers did more business and ultimately earned more money".[70]

Criticism and controversies

The Harvard Business Review argues that "sharing economy" is a misnomer, and that the correct word for this activity is "access economy". The authors say, "When "sharing" is market-mediated—when a company is an intermediary between consumers who don't know each other—it is no longer sharing at all. Rather, consumers are paying to access someone else's goods or services."[12] The article goes on to show that companies (such as Uber) who understand this, and whose marketing highlights the financial benefits to participants, are successful, while companies (such as Lyft) whose marketing highlights the social benefits of the service are less successful.

The notion of "sharing economy" has often been considered as an oxymoron, and a misnomer for actual commercial exchanges.[71] Arnould and Rose[72] proposed to replace the misleading concept of "sharing" by that of mutuality or mutualization. A distinction can therefore be made between free mutualization such as genuine sharing and for-profit mutualization in the likes of Uber, Airbnb, or Taskrabbit.[73][74][75] To Ritzer,[76] this current trend towards increased consumer input in commercial exchanges refers to the notion of prosumption, which, as such, is not new. The mutualization of resources is for example well known in business-to-business (B2B) like heavy machinery in agriculture and forestry as well as in business-to-consumer (B2C) like self-service laundries. But three major drivers enable consumer-to-consumer (C2C) mutualization of resources for a broad variety of new goods and services as well as new industries. First, customer behaviour for many goods and services changes from ownership to sharing. Second, online social networks and electronic markets more easily link consumers. And third, mobile devices and electronic services make the use of shared goods and services more convenient (e.g. smartphone app instead of physical key).[77]

Salon writes that "the sharing economy ... [is] not the Internet 'gift economy' as originally conceived, a utopia in which we all benefit from our voluntary contributions. It's something quite different—the relentless co-optation of the gift economy by market capitalism. The sharing economy, as practiced by Silicon Valley, is a betrayal of the gift economy. The potlatch has been paved over, and replaced with a digital shopping mall."[78][79][80][81]

Oxford Internet Institute, Economic Geographer, Graham has argued that key parts of the sharing economy impose a new balance of power onto workers.[82] By bringing together workers in low- and high-income countries, gig economy platforms that are not geographically-confined can bring about a 'race to the bottom' for workers.

Relationship to job loss

New York Magazine wrote that the sharing economy has succeeded in large part because the real economy has been struggling. Specifically, in the magazine's view, the sharing economy succeeds because of a depressed labor market, in which "lots of people are trying to fill holes in their income by monetizing their stuff and their labor in creative ways," and that in many cases, people join the sharing economy because they've recently lost a full-time job, including a few cases where the pricing structure of the sharing economy may have made their old jobs less profitable (e.g. full-time taxi drivers who may have switched to Lyft or Uber). The magazine writes that "In almost every case, what compels people to open up their homes and cars to complete strangers is money, not trust. ... Tools that help people trust in the kindness of strangers might be pushing hesitant sharing-economy participants over the threshold to adoption. But what's getting them to the threshold in the first place is a damaged economy, and harmful public policy that has forced millions of people to look to odd jobs for sustenance."[83][84][85]

The Huffington Post wrote that some people believe the recent recession lead to the expansion of the sharing economy because people could easily employ themselves through the services that these companies offer. However, this concept is only hiding the fact that such employment is only a new face for contractual work and temporary employment that doesn't provide the necessary safeguards for modern living. When companies use contract based employment, the "advantage for a business of using such non-regular workers is obvious: It can lower labor costs dramatically, often by 30 percent, since it is not responsible for health benefits, social security, unemployment or injured workers' compensation, paid sick or vacation leave and more. Contract workers, who are barred from forming unions and have no grievance procedure, can be dismissed without notice".[69]

Circumventing labor protection law(s)

Xconomy wrote about the debate over the status of the workers within the sharing economy, whether they should be treated as contract workers or employees of the companies. This issue seems to be most relevant among sharing economy companies such as Uber. The reason this has become such a big issue is that the two types of workers are treated very differently. Contract workers are not guaranteed any benefits and pay can be below average. However, if they are employees, they are granted access to benefits and pay is generally higher. The State of California is trying to go after Uber and make them pay a fine to compensate workers fairly. The California Public Utilities Commission was working on a case that "addresses the same underlying issue seen in the contract worker controversy—whether the new ways of operating in the sharing economy model should be subject to the same regulations governing traditional businesses".[86] Business Insider wrote that companies such as Airbnb and Uber do not share their reputation data with the very users who it belongs to. This is an issue since no matter how well you behave on any one platform, your reputation doesn't travel with you. This fragmentation has some negative consequences, such as the Airbnb squatters who had previously deceived Kickstarter users to the tune of $40,000.[87] Sharing data between these platforms could have prevented the repeat incident. Business Insider's view is that since the Sharing Economy is in its infancy, this has been accepted. However, as the industry matures, this will need to change.[88]

Giana Eckhardt and Fleura Bardhi say that the sharing economy promotes and prioritizes cheap fares and low costs rather than personal relationships, which is tied to similar issues in crowdsourcing. For example, Zipcar is advertised as a ride-sharing service, but it's been brought into consideration that the consumers reap similar benefits from Zipcar as they would from, say, a hotel. In this example, there is minimal social interaction going on and the primary concern is the low cost. Other examples many include myriad other sharing economies such as AirBnB or Uber. Because of this, the "sharing economy" may not be about sharing but rather about access. Giana Eckhardt and Fleura Bardhi say the "sharing" economy has taught people to prioritize cheap and easy access over interpersonal communication, and the value of going the extra mile for those interactions has diminished.[89]

Benefits not accrued evenly

Andrew Leonard,[90][91][92] Evgeny Morozov,[93] Bernard Marszalek,[94] Dean Baker,[95][96] and Andrew Keen[97] criticized the for-profit sector of the sharing economy, writing that sharing economy businesses "extract" profits from their given sector by "successfully [making] an end run around the existing costs of doing business" - taxes, regulations, and insurance. Similarly, In the context of online freelancing marketplaces, there have been worries that the sharing economy could result in a 'race to the bottom' in terms or wages and benefits: as millions of new workers from low-income countries come online.[98][99]

Susie Cagle wrote that the benefits big sharing economy players might be making for themselves are "not exactly" trickling down, and that the sharing economy "doesn't build trust" because where it builds new connections, it often "replicates old patterns of privileged access for some, and denial for others."[100] William Alden wrote that "The so-called sharing economy is supposed to offer a new kind of capitalism, one where regular folks, enabled by efficient online platforms, can turn their fallow assets into cash machines ... But the reality is that these markets also tend to attract a class of well-heeled professional operators, who outperform the amateurs—just like the rest of the economy."[101]

The local economic benefit of the sharing economy is offset by its current form, which is that huge tech companies reap a great deal of the profit in many cases. For example, Uber, which is estimated to be worth $50B as of mid-2015,[102] takes up to 30% commission from the gross revenue of its drivers,[103] leaving many drivers making less than minimum wage.[104]

Types of sharing

Template:Multicol Agriculture

Finance

Food

Travel

Real estate

- Airbnb

- Co-housing

- Coliving

- Collaborative workspace

- Couchsurfing

- Emergencybnb

- Home exchange

- Peer-to-peer property rental

Template:Multicol-break Labor

Property

- Bartering

- Book swapping

- Borrowing center

- Clothes swapping

- Fractional ownership

- Freecycling

- Free store

- Peer-to-peer renting

- List of tool-lending libraries

- Toy library

Transportation

- Bike sharing system

- Carpool

- Carsharing and peer-to-peer carsharing

- Cycling

- Real-time ridesharing

- Share taxi

- Share parking space

- Transfer cars

- Transportation network company

Template:Multicol-break Governance

Business

Technology

Digital rights

Other

See also

- Access economy

- Collaborative consumption

- Co-creation

- Collaborative finance

- Collaborative innovation network

- Commons-based peer production

- Cooperative

- Creative Commons

- Digital Collaboration

- Internet of Things

- Internet of Services

- Online platforms for collaborative consumption

- Open Knowledge Foundation

- Open Source

- P2P Foundation

- Peer-to-peer (meme)

- Recommerce

- Reputation capital

- Reputation systems

- Secondhand good

- Social collaboration

- Social commerce

- Social dining

- Social Peer-to-Peer Processes

- Two-sided market

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d e Hamari, Juho; Sjöklint, Mimmi; Ukkonen, Antti (2016). "The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 67 (9): 2047–2059. doi:10.1002/asi.23552.

- ^ Tuttle, Brad. "Can We Stop Pretending the Sharing Economy Is All About Sharing?". MONEY.com. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- ^ Leslie Hook (22 June 2016). "Review – 'The Sharing Economy', by Arun Sundararajan" ((registration required)). Financial Times. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ a b Cohen, Boyd; Kietzmann, Jan (2014). "Ride On! Mobility Business Models for the Sharing Economy". Organization & Environment. 27 (3): 279–296. doi:10.1177/1086026614546199.

- ^ a b Ertz, Myriam; Lecompte, Agnes; Durif, Fabien (2016). "Neutralization in collaborative consumption: An exploration of justifications relating to a controversial service". Managerial Marketing eJournal.

- ^ Sundararajan, Arun. "From Zipcar to the Sharing Economy". January 3, 2013. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Geron, Tomio (November 9, 2012). "Airbnb Had $56 Million Impact On San Francisco: Study". Forbes. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Botsman, Rachel; Rogers, Roo (2011). What's mine is yours : how collaborative consumption is changing the way we live (Rev. and updated ed.). London: Collins. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-00-739591-0.

- ^ Botsman, Rachel; Rogers, Roo (2011). What's Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way We Live. HarperCollins Business. ISBN 0-00-739591-4.

- ^ "From homes to meals to cars, 'sharing' has changed the face of travel". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ^ "Harvard Business School Club of New York – What's Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption". Hbscny.org. 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ a b c "The Sharing Economy Isn't About Sharing at All". Harvard Business Review. 2015-01-28. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- ^ a b Alex Stephany (2015). The Business of Sharing: Making it in the New Sharing Economy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1137376171.

- ^

Benita Matofska (2016-08-01). "What is the Sharing Economy?". The people who share. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

A Sharing Economy enables different forms of value exchange and is a hybrid economy. It encompasses the following aspects: swapping, exchanging, collective purchasing, collaborative consumption, shared ownership, shared value, co-operatives, co-creation, recycling, upcycling, re-distribution, trading used goods, renting, borrowing, lending, subscription based models, peer-to-peer, collaborative economy, circular economy, on-demand economy, gig economy, crowd economy, pay-as-you-use economy, wikinomics, peer-to-peer lending, micro financing, micro-entrepreneurship, social media, the Mesh, social enterprise, futurology, crowdfunding, crowdsourcing, cradle-to-cradle, open source, open data, user generated content (UGC) and public services.

- ^ a b Pierre Goudin (January 2016). "The Cost of Non-Europe in the Sharing Economy" (PDF). EPRS : European Parliamentary Research Service. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- ^ a b c d Rudy Telles Jr (June 3, 2016). "Digital Matching Firms: A New Definition in the "Sharing Economy" Space" (PDF). United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- ^ Zoe Oja Tucker (8 Nov 2015). "The True Sharing Economy". East Bay Express. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- ^ a b Kenneth Olmstead and Aaron Smith (20 May 2016). "How Americans define the sharing economy". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- ^ Sarah Kessler (14 Oct 2015). "The "Sharing Economy" Is Dead, And We Killed It". Fast Company (magazine). Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Sarah O'Connor (14 June 2016). "The gig economy is neither 'sharing' nor 'collaborative'" ((registration required)). Financial Times. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Juliet Schor (October 2014). "Debating the Sharing Economy". Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas (20 July 2013). "Welcome to the Sharing Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Rosenberg, Tina (5 June 2013). "It's Not Just Nice to Share, It's the Future". The New York Times.

- ^ Wang, Ray. "Monday's Musings: Four Elements for A #SharingEconomy Biz Model In #MatrixCommerce". May 26, 2013. Software Insider. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "The Collaborative Economy". June 4, 2013. Altimeter Group. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Ertz, Myriam; Durif, Fabien; Arcand, Manon (2016). "An analysis of the origins of collaborative consumption and its implications for marketing". Academy of Marketing Studies Journal. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Homestay is the origin of Sharing Economy". PR Newswire. 2014-03-11. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Benkler, Yochai (2002). "Coase's Penguin, or, Linux and The Nature of the Firm" (PDF). The Yale Law Journal. 112. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Benkler, Yochai (2004). "Sharing Nicely: On Shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production". The Yale Law Journal. 114. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Felson, Marcus and Joe L. Spaeth (1978), "Community Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A routine activity approach," American Behavioral Scientist, 21 (March–April), 614–24.

- ^ "10 Ideas That Will Change The World". Time. March 17, 2011.

- ^ "Support for the sharing economy" (PDF). H. M. Treasury, Budget 2015, section 1.193.

- ^ "Review: The Business Of Sharing". May 5, 2015.

- ^ John Hawksworth and Robert Vaughan (2014). "The sharing economy – sizing the revenue opportunity". PricewaterhouseCoopers. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- ^ a b Ertz, Myriam; Lecompte, Agnès; Durif, Fabien (2016). "Neutralization in collaborative consumption: An exploration of justifications relating to a controversial service". Managerial Marketing eJournal.

- ^ a b Rachel Botsman; Roo Rogers (1922-01-01). "Beyond Zipcar: Collaborative Consumption". Hbr.org. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ "DriveNow: BMW and Sixt Joint Venture for premium car sharing".

- ^ Owyang, Jeremiah (24 February 2015). "The mobile technology stack for the Collaborative Economy". VentureBeat. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Karim R. Lakhani (1922-01-01). "Using the Crowd as an Innovation Partner". Hbr.org. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ Mazmanian, Adam (May 22, 2013). "Can open data change the culture of government?". Federal Computer Week.

- ^ "Data.gov". Data.gov. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ "London Datastore". Data.london.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ Hammell, Richard. "Open Data: Driving Growth, Ingenuity and Innovation" (PDF). Deloitte Consulting. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Brindley, William. "How Open Data can Save Lives". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Charles, Green (May 2, 2012). "Trusted and Being Trusted in the Sharing Economy". Forbes. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Hawlitschek, Florian; Teubner, Timm; Weinhardt, Christof (2016). "Trust in the Sharing Economy". Swiss Journal of Business Research and Practice. 70 (1): 26–44. doi:10.5771/0042-059X-2016-1-26.

- ^ "Car Sharing and Pooling: Reducing Car Over-Population and Collaborative Consumption | Energy Seminar". Energyseminar.stanford.edu. 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ Boudreau, Kevin; Karim R. Lakhani. "Using the Crowd as an Innovation Partner". April 2013. Harvard Business Review.

- ^ Bloyd-Peshkin, Sharon (October 21, 2009). "Built to Trash". In These Times. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Griffith, Saul. "Everyday Inventions". TED. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Open Data Handbook". 2011, 2012. Open Knowledge Foundation. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "ICT Facts and Figures, 2013" (PDF). 2013. International Telecommunications Union. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Parr, Ben (August 3, 2009). "What the F**k is Social Media?". Mashable. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Preston, Felix. "A Global Redesign? Shaping the Circular Economy" (PDF). March, 2012. Chatham House. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Geron, Tobio (January 23, 2013). "Airbnb and the Unstoppable Rise of the Share Economy". Forbes. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Brady, Diane (24 September 2014). "The Environmental Case for the Sharing Economy". Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Rudenko, Anna (16 August 2013). "The collaborative consumption on the rise: why shared economy is winning over the "capitalism of me"". Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ a b Parsons, Adam (5 March 2014). "The sharing economy: a short introduction to its political evolution". opendemocracy.net. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Bradshaw, Della (22 April 2015). "Sharing economy benefits lower income groups". FT.com. Retrieved 10 July 2015.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Williams-Grut, Oscar (20 March 2015). "Silicon Round-up: Blockchain banking to be on the slate for new regulator?". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 10 July 2015.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Cohen, Boyd; Muñoz, Pablo (2015). "Sharing cities and sustainable consumption and production: towards an integrated framework". Journal of Cleaner Production. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.133.

- ^ Jerome, Joseph (2015-06-08). "User Reputation: Building Trust and Addressing Privacy Issues in the Sharing Economy". Future of Privacy Forum. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ Geron, Tomio. "Airbnb And The Unstoppable Rise Of The Share Economy". Forbes. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ Afp (2015-02-03). "'Sharing economy' reshapes markets, as complaints rise | Daily Mail Online". London: Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ "Uber Said to Seek $1.5 Billion in Funds at $50 Billion Valuation". Bloomberb Business. 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2015-07-09.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b "Comparing Airbnb and Hotel Rates Around the Globe | Busbud blog". Busbud blog. 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ Emily Guendelsberger (May 7, 2015). "I was an undercover Uber driver". Philadelphia Citypaper. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ^ Natasha Singer and Mike Isaac (May 9, 2015). "An App That Helps Drivers Earn the Most From Their Trips". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

At first I thought I was earning money

- ^ a b "How the Sharing Economy Screws American Workers". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- ^ a b Santora, Marc; Surico, John (2016-02-01). "Uber Drivers in New York City Protest Fare Cuts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- ^ Slee, Tom (2015). What's yours is mine. New York: OR Books. p. 216. ISBN 1-68219-022-6.

- ^ Arnould, Eric. J.; Rose, Alexander S. (2016). "Mutuality: Critique and substitute for Belk's sharing". Marketing Theory. 16 (1): 75. doi:10.1177/1470593115572669.

- ^ Ertz, Myriam; Durif, Fabien; Arcand, Manon (2016). "Collaborative consumption: Conceptual snapshot at a buzzword". Academy of Strategic Management Journal.

- ^ Ertz, Myriam; Durif, Fabien; Arcand, Manon (2016). "Collaborative consumption or the rise of the two-sided consumer". International Journal of Business and Management. 6 (6).

- ^ Laurell, Christofer; Sandström, Christian (June 2016). "Analysing Uber in social media – disruptive technology or institutional disruption?". International Journal of Innovation Management. 20 (5): 1640013. doi:10.1142/S1363919616400132. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Ritzer, George (2014). "Prosumption: Evolution, revolution, or eternal return of the same?". Journal of Consumer Culture. 14 (1). Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Ertz, Myriam (2015). Du Web 2.0 a la seconde vie des objets: Le role de la technologie internet. Munich: GRIN Verlag. p. 52. ISBN 3-668-04210-1.

- ^ Andrew Leonard, "Sharing economy" shams: Deception at the core of the Internet's hottest businesses, Salon.com, 2014.03.14

- ^ Andrew Leonard, You're not fooling us, Uber! 8 reasons why the "sharing economy" is all about corporate greed, Salon.com, 2014.02.17

- ^ Tom Slee, The secret libertarianism of Uber & Airbnb, Salon.com, 2014.01.28

- ^ Anya Kamenetz, AirBnb wins New York court victory, but the city still present challenges for the popular room-finding site, Fast Company and Salon, 2013.09.30

- ^ Graham, Mark. "Digital work marketplaces impose a new balance of power". New Internationalist. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ Kevin Roose, The Sharing Economy Isn't About Trust, It's About Desperation (2014-04-24), New York Magazine

- ^ Kevin Roose, Does Silicon Valley Have a Contract-Worker Problem? (2014-09-18), New York Magazine

- ^ A Secret of Uber's Success: Struggling Workers (2014-10-02), Bloomberg.com

- ^ "Sharing Economy Companies Sharing the Heat In Contractor Controversy | Xconomy". Xconomy. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- ^ Kevin Montgomery, Airbnb Squatters Also Swindled $40,000 From Kickstarter, 2014-07-28

- ^ Patrick J. Stewart, Reputation And The Sharing Economy (2014-10-23), "Business Insider

- ^ Giana Eckhardt and Fleura Bardhi, The Sharing Economy isn't About Sharing at All (2015-02-09), Harvard Business Review

- ^ Millennials will not be regulated, Andrew Leonard, Salon.com, 2013.09.20

- ^ The sharing economy muscles up, Andrew Leonard, Salon.com, 2013.09.17

- ^ Libertarians' anti-government crusade: Now there's an app for that (2014-06-27), Andrew Leonard, Salon

- ^ Evgeny Morozov. Don't believe the hype, the 'sharing economy' masks a failing economy (September 2014), The Guardian (UK)

- ^ The New Boss – You – Just Like the Old Boss: The Sharing Economy = Brand Yourself (2014.05.26), BERNARD MARSZALEK, CounterPunch

- ^ How AirBnB and Uber Cab are Facilitating Rip-Offs: The Downside of the Sharing Economy (2014.05.28), Dean Baker, CounterPunch

- ^ How Uber Disrupts the Taxi Market (2015.02.12), Dean Baker, CounterPunch

- ^ The Internet is not the Answer, an interview with Andrew Keen at the Digital Life Design (DLD) 2015 Annual Conference. Posted on the official You Tube Channel of DLD

- ^ Graham, Mark (2016). "Digital work marketplaces impose a new balance of power". New Internationalist.

- ^ Graham, Mark (2016). "Organising in the "digital wild west": can strategic bottlenecks help prevent a race to the bottom for online workers?". Union Solidarity International.

- ^ The Case Against Sharing: On access, scarcity, and trust (2014-05-28), Susie Cagle, Medium.com

- ^ The Business Tycoons of Airbnb, The New York Times

- ^ Afp (2015-02-03). "'Sharing economy' reshapes markets, as complaints rise | Daily Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ Huet, Ellen (2015-05-18). "Uber Tests Taking Even More From Its Drivers With 30% Commission". Forbes. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- ^ "A Philadelphia journalist went undercover as an Uber driver — here's how much she made". MSN. 2015-05-09. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

Further reading

- A Policy Agenda for the Sharing Economy, The Urbanist, October 2012

- Kostakis, V., and Bauwens, M. (2014) Network Society and Future Scenarios for a Collaborative Economy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- All Eyes on the Sharing Economy, The Economist, March 9, 2013

- The Twilight of the Sharing Economy—or the Dawn?, The Atlantic, May 7, 2013

- The End of Ownership, Boston Magazine, May 2013

- Leonard, Andrew (January 2012). "The Economy of Sharing". Sunset Magazine.

- Nanos, Janelle (May 2013). "The End of Ownership". Boston Magazine.

- The Sharing Economy: Embracing Change with Caution, Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum, June 2015

- Adapting to the Sharing Economy, MIT Sloan Management Review, 56(2), 2015, S. 71–77.