Solresol

| Solresol | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created by | François Sudre |

| Date | 1827 |

| Purpose | |

| Sources | a priori |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2009) |

Solresol is an artificial language devised by François Sudre, beginning in 1827. His major book on it, Langue musicale universelle, was published after his death in 1866[citation needed], though he had already been publicizing it for some years. Solresol enjoyed a brief spell of popularity, reaching its pinnacle with Boleslas Gajewski's 1902 posthumous publication of Grammaire du Solresol.

The teaching of sign languages to the deaf was discouraged between 1880 and 1991 in France, contributing to Solresol's descent into obscurity. After a few years of popularity, Solresol nearly vanished in the face of more successful languages, such as Volapük and Esperanto. There is still a small community of Solresol enthusiasts scattered across the world, better able to communicate with one another now more than before thanks to the Internet.

Phonology

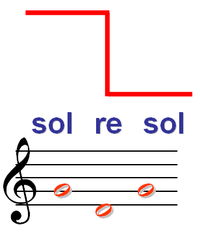

Solresol words are made up of from one to five syllables or notes. Each of these may be one of only seven basic phonemes, which may in turn be accented or lengthened. There is another phoneme, silence, which is used to separate words: words cannot be run together as they are in English.

The phonemes can be represented in a number of different ways – as the seven musical notes in an octave, as spoken syllables (based on solfège, a way of identifying musical notes), with the seven colours of the rainbow, symbols, hand gestures etc. Thus, theoretically Solresol communication can be done through speaking, singing, flags of different color – even painting.

Vocabulary

As in Ro, the longer words are divided into categories of meaning, based on their first syllable, or note. Words beginning with 'sol' have meanings related to arts and sciences, or, if they begin with 'solsol', sickness and medicine (e.g., solresol, "language"; solsolredo, "migraine"). Like other constructed languages with a priori vocabulary, Solresol faces considerable problems in categorizing the real world around it sensibly. The last couple of syllables may be arbitrary, to capture distinctions such as "apple" vs "pear" which do not fit simple categories.

Feminine words are formed by accenting the last syllable, and plurals by lengthening it.

A unique feature of Solresol is that meanings are negated by reversing the syllables in words. For instance fala means good or tasty, and lafa means bad. It is unclear how this interacts with the way words are categorized by their first note.

The following table shows the words of up to two syllables:

| First (below) and second (right) syllables | No second syllable | -do | -re | -mi | -fa | -sol | -la | -si |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do- | no, not, neither, nor | (past) | I, me | you [sg] | he | self, oneself | one, someone | other |

| Re- | and, as well as | my, mine | (pluperfect) | your, yours [sg] | his | our, ours | your, yours [pl] | their |

| Mi- | or, or even | for, in order to/that | who, which (rel pron), that (conj) | (future) | whose, of which | well (adv) | here/there is, behold | good evening/night |

| Fa- | to | what? | with, jointly | this, that | (conditional) | why, for what reason | good, tasty, delectable | much, very, extremely |

| Sol- | if | but | in, within | wrong, ill (adv) | because | (imperative) | perpetually, always, without end, without ceasing | thank, thanks |

| La- | the | nothing, no one, nobody | by | here, there | bad | never, at no time | (present participle) | of |

| Si- | yes, okay, gladly, agreed | the same (thing) | each, every | good morning/afternoon | little, scarcely | mister, sir* | young man, bachelor* | (passive participle) |

* Feminine versions are formed by stressing the last syllable.

Grammar

Apart from stress and length, solresol words are not inflected. Word order is also rather strict.

Solresol marks feminine gender and plural number, by stressing or lengthening the last syllable a word:

- resimire brother, resimiré sister

- resimiree brothers, resimiréé sisters

This only affects the first word in a noun phrase. That is, it only affects a noun when the noun is alone, as above; any determiner ('the', 'my', etc.) will take the gender or number marking instead:

- redo resimire my brother, redó resimire my sister

- redoo resimire my brothers, redóó resimire my sisters

Parts of speech are derived from verbs by lengthening (or stressing?)[1] one of the syllables: abstract noun (1st syllable), agent/doer (2nd syllable), adjective (penult), adverb (last syllable). For example,

- midofa to prefer, miidofa preference, midoofa preferable, midofaa preferably

- resolmila to continue, reesolmila continuation, resoolmila one who continues, resolmiila continual, resolmilaa continually

Questions are formed by inverted subject and verb.

The various tense-and-mood particles are the double syllables, as given in vocabulary above. In addition, passive verbs are formed with faremi between this particle and the verb. The subjunctive is formed with mire before the pronoun. The negative do only appears once in the clause, before the word it negates.

The word fasi before a noun or adjective is augmentative; after it is superlative. Sifa is the opposite (diminutive):

- fala good, fasi fala very good, fala fasi excellent, the best; sifa fala okay, fala sifa not very good (and similarly with lafa bad)

- sisire wind, fasi sisire gale, sisire fasi cyclone; sifa sisire breeze, sisire sifa movement of air

Additional features

- impartial and relatively simple

- integrated systems (signs, colors, etc.) for most different handicapped people, immediately operative without special learning)

- gives fast learning success to illiterate people (only 7 syllables or signs or 10 letters to know and to recognize)

- very simple but effective system to differentiate the function of the words in the sentences

See also

References

- ^ The description is not clear.

- Umberto Eco. The Search for the Perfect Language. 1993. ISBN 0-631-20510-1

External links

- Langmaker.com about Solresol

- html-version of the text of the book of François Sudre edition from 1866, Gajewski's Grammar of Solresol, edition 1902, translated in different languages, dictionary of Solresol with more than 13.000 French equivalents in a MySQL data base, and different other texts on artificial languages (Esperanto from 1897, Ido from 1908, Occidental from 1930, and soon, Universalglot, Jean Pirro, from 1868)

- Omniglot on the various ways of writing Solresol

- The Athanasius Kircher Society's blog entry on Solresol

- Grammar of Solresol by Boleslas Gajewski

- Solresol-English/French Mini-Dictionary

- Solresol text collection including full Solresol–French dictionary