Squatting in England and Wales

Squatting in England and Wales usually refers to a person who is not the owner, taking possession of land or an empty house. People squat for a variety of reasons which include needing a home,[1] protest,[2] poverty, and recreation.[3] Many squats are residential, some are also opened as social centres. Land may be occupied by New Age travellers or treesitters.

There have been waves of squatting through British history. The BBC states that squatting was "a big issue in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 and again for the Diggers in the 17th Century [who] were peasants who cultivated waste and common land, claiming it as their rightful due" and that squatting was a necessity after the Second World War when so many were homeless.[4] A more recent wave began in the late 1960s in the midst of a housing crisis.

Many squatters legalised their homes or projects in the 1980s, for example Bonnington Square and Frestonia in London. More recently, there are still isolated examples such as the Invisible Circus in Bristol.

Under Section 144 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, squatting in residential property became a criminal offence on 1 September 2012.[5][6] Squatting in non-residential property may be a civil or a criminal matter, depending upon the circumstances,[7] and repossession by the owners, occupiers or intended occupiers may require legal process or police action.

History

During the Anglo-Saxon period, before the Norman Conquest of 1066, commoners were able to grow crops and graze their animals, by a system of customary rights, on common land.[8] Traditionally in an English village there were several classes of people. At the lower end were the incomers known as borderers or squatters, who would erect a cottage or a hovel on common or waste ground to house themselves and would pay rent to the Manorial lord or would work on his demesne several days a week. The building of the cottage was generally tolerated or even sanctioned under customary right.[9][10] Initially these rights were respected by the Norman conquerors, but over time landowners started to enclose land and deprive commoners of their ancient rights. Farm labourers would lose the ability to feed themselves and were dependent on their Manorial lord for an income. Squatters were made homeless.[8][11]

16th- and 17th-century

In 16th- and 17th-century Wales, an expansion in population as well as taxation policy led to a move of people into the Welsh countryside, where they squatted on common land. These squatters built their own property under the assumption of a fictional piece of folklore, leading to the developments of small holdings around a Tŷ unnos, or "house in a night".

In Elizabethan times, there was a common belief that if a house was erected by a squatter and their friends on waste ground overnight, then they had the right of undisturbed possession.[12] To make it difficult for squatters to build, an act was passed known as the Erection of Cottages Act 1588 whereby a cottage could only be built as long as it had a minimum of 4 acres (1.62 ha; 0.01 sq mi) of land associated with it.[12][13] The act was repealed by the Erection of Cottages Act 1775 (15 Geo. III c. 32).[14]

In 1649 at St George's Hill, Weybridge in Surrey, Gerrard Winstanley and others calling themselves The True Levellers occupied disused common land and cultivated it collectively in the hope that their actions would inspire other poor people to follow their lead. Gerrard Winstanley stated that "the poorest man hath as true a title and just right to the land as the richest man".[15]

Post-World War II

There was a huge squatting movement involving ex-servicemen and their families following World War II. In Brighton, Harry Cowley and the Vigilantes installed families in empty properties all around the country. In London suburbs and villages such as Chalfont St Giles, families occupied derelict camps and in some cases stayed there until the mid-1950s.[16] As word spread, more and more people squatted until there were an estimated 45,000 in total.[17] On 10 October, Aneurin Bevan reported to the House of Commons that 1,038 camps in England and Wales were occupied by 39,535 people.[18]

Whilst the Government prevaricated, there was considerable public support for the squatters, since they were perceived as honest people simply taking action to house themselves. Clementine Churchill, wife of the ex-Prime Minister, commented in August 1946: "These people are referred to by the ungraceful term 'squatters', and I wish the press would not use this word about respectable citizens whose only desire is to have a home."[18]

On 8 September 1946, 1,500 people squatted flats in Kensington, Pimlico and St. Johns Wood. This action, termed the 'Great Sunday Squat' garnered much media attention and resulted in five of the leaders being arrested for 'conspiring to incite and direct trespass.' The squatters left the apartments but did receive temporary accommodation. A sympathetic judge merely bound the squatters over to good behaviour.[18]

1960s

In the context of a severe housing crisis, the late 1960s saw the development of the Family Squatting Movement, which sought to mobilise people to take control of empty properties and use them to house homeless families from the council housing waiting list. This movement was originally based in London, where Ron Bailey and Jim Radford were instrumental in helping to establish family squatting campaigns in several London boroughs and later the Family Squatting Advisory Service. Several local Family Squatting Associations signed agreements with borough councils to use empty properties under licence, although only after some lengthy and bitter campaigns had been fought—most particularly in the borough of Redbridge.[19] Bailey commented in 2005 that "The whole concept of community-based housing associations – that's where it all started, with squatting groups. It shows that the solution to housing problems isn't estate based, it should be based on mutual aid. The government should do all it can to enable self-help groups to flourish."[20]

Since 1967, the Principality of Sealand has existed as an unrecognised micronation on HM Fort Roughs, a sea fort off the coast of Suffolk. It was occupied by Paddy Roy Bates, who styled himself as His Royal Highness Prince Roy.

In 1969, members of the London Street Commune squatted a mansion at 144 Piccadilly in central London to highlight the issue of homelessness but were quickly evicted.[21] The extensive media coverage created what one commune leader, 'Dr John', described as hysterical fear of squatters, creating a moral panic.[22] The Eel Pie Island Hotel was occupied by a small group of local anarchists including illustrator Clifford Harper. By 1970 it had become the UK's largest hippy commune.[23]

St Agnes Place was a squatted street in Kennington, South London, which was occupied from 1969 until 2005.[24]

1970s

By the early 1970s, there was a growing conflict between the original activists of the Family Squatting Movement and a newer wave of squatters who simply rejected the right of landlords to charge rent and who believed (or claimed to) that seizing property and living rent-free was a revolutionary political act or more practically decided it was a good way to save money. These new-wave squatters (often young and single rather than homeless families) were a mixture of anarchists, Trotskyists—the International Marxist Group (IMG) being especially prominent—and self-proclaimed hippie dropouts, and they denounced the idea that squatters should seek to make agreements with local Councils to use empty property and that Squatting Associations should then become landlords (or Self Help Housing Associations as they were sometimes styled) in their own right and charge rent.

The Advisory Service for Squatters (ASS) continued the work of the Family Squatting Advisory Service, running a volunteer service helping squatters. ASS has been in continuous existence for almost forty years. It publishes the Squatters' Handbook and has drafted a legal warning to be used by squatters.[25]

Local Authority Housing Departments, facing rising court costs when evicting squatters, often resorted to taking out the plumbing and toilets in empty buildings to deter squatters. In the 1970s, some housing councils would attempt to deter squatters from entering their properties by "gutting" the houses, rendering them uninhabitable by pouring concrete into toilets and sinks or smashing the ceilings and staircases.[19]

Activists such as Terry Fitzpatrick teamed up with the local community in Whitechapel to form the Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG) in 1976. At a time when the National Front was a threat in the area, Bengali families found strength squatting in numbers. Members of Race Today were involved in BHAG. When the Greater London Council declared an amnesty for squatters in 1977, they offered the Bengali families estates in the area.[26]

In 1979, there were estimated to be 50,000 squatters throughout Britain, with the majority (30,000) living in London.[27] There was a London's Squatters' Union in which Piers Corbyn was involved. For eighteen months, it was housed at Huntley Street, where over 150 people lived in 52 flats. The union organised festivals and provided homes for the homeless.[28]

Housing activists including Jim Radford and Jack Dromey occupied the Centre Point building in central London to protest homelessness. In west London, squatters occupied a triangle of land and called it Frestonia. When they were threatened with eviction, they set up a free state which attempted to secede from England. Actor David Rappaport was the foreign minister, while playwright Heathcote Williams served as ambassador to Great Britain. The squatters later formed themselves into a housing co-operative which still owns the buildings.[29]

The BBC documentary series Lefties profiled a squatted street called Villa Road in Brixton, which is still in existence.

Tolmers Square

In Somers Town, between Tottenham Court Road and Euston station in central London, Tolmers Square was occupied by more than one hundred squatters, who engaged with local groups to fight for a redevelopment plan which fitted the community. After a long struggle, they were successful.[30]

Demolitions and threats to Georgian Bloomsbury and to Tolmers Square in Euston (the 'locus classicus of London's intellectual squatting movement'), succeeded anew in drawing public attention to the plight of the squares, and precipitated the initial stirrings of the movement for their preservation.[31]

Students from the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment (at that time called the School of Environmental Studies) noticed in 1973 that the Georgian terraced housing composing the nearby Tolmers Square was threatened with demolition. The students, Jill Baldry, Elizabeth Britton, Pedro George, Pete Henshaw and Nick Wates, decided to make their final year undergraduate project about the square. They spoke to local residents and ended up joining the struggle against redevelopment.[32]

The Tolmers Village Association was founded to represent the interests of small business owners, tenants, owners and squatters, allied against the council and the developers.[30] It published an infosheet called Tolmers News and produced a report, Tolmers Destroyed, to publicise the struggle. By 1975, 'Tolmers Village' had 49 squats housing over 180 people. Philip Thompson made a documentary film called Tolmers: Beginning or End?, which screened twice on BBC2.[32]

The squatters lived there for six years, during which time Alara Wholefoods & Community Foods started up. Alara grew to become the largest wholefood company in Britain in the 1980s and 1990s.[33] The squatters were eventually evicted but many of the proposals made by their 1978 Tolmers Peoples Plan were included in the revamped development plans, which resulted in the council making a compulsory purchase of the land from the developer and building housing instead of offices. Nick Wates writes that "It was only by taking direct action that anyone could intervene. By occupying empty buildings, squatters were able to halt the decline, revive the community and revive leadership in the struggle against the developers."[30]

1980s

The 121 Centre was set up on Railton Road in Brixton, London, having first been squatted by the black feminist Olive Morris. Until its eviction in 1999, the 121 hosted events and in the 1980s printed a squatters newspaper called Crowbar and the anarchist Black Flag magazine in its basement.[34] Centro Iberico was an old school squatted as a social centre in the 1980s, following on from the Wapping Autonomy Centre. Comedians Harry Enfield, Charlie Higson and Paul Whitehouse all squatted in Hackney in east London.[35]

Elsewhere in England, there were sizeable squatting communities in Brighton, Bristol, Cambridge, Leicester and Portsmouth.[36] In Bristol, in the mid-1980s, squatters had the Full Marx bookshop, the Demolition Ballroom and the Demolition Diner, all on Cheltenham Road.[34]

1990s

Road protests such as those against the M3 at Twyford Down, M11 link road in London and the Newbury bypass in Berkshire used squatting as a tactic to slow down development.

Squatters in Brighton formed a group called Justice? to resist the Criminal Justice Bill and squatted an old Courthouse. They later set up a Squatters Estate Agency which received national media coverage. The 2012 Brighton Photo Biennial focused on 'Agents of Change' and released a full colour pamphlet entitled 'Another Space: Political Squatting in Brighton 1994 – present.'[37] Projects such as the aforementioned estate agency, a community garden, exhibitions and an anti-supermarket project were all featured. The curator commented that "While millionaires leave 'spare' houses empty for months on end and Tesco buy up land to be left vacant indefinitely, so called public space continues to diminish. By opening buildings to the public to make and share art, squatters create temporary autonomous spaces that radically refute this logic."[38]

2000s

In 2003, it was estimated that there were 15,000 squatters in England and Wales.[39] In 2012, the Ministry of Justice deemed the figure to be 20,000.[40]

According to statistics compiled by the Empty Homes Agency in 2009, the most empty homes in the UK were in Birmingham (21,532), Leeds (24,796) Liverpool (20,860) and Manchester (24,955).[41] The fewest empty homes were in South East England and East Anglia. Groups such as Justice Not Crisis campaigned for more social housing.

There have been squatted social centres in many UK cities, linked through the UK Social Centre Network. The OKasional Cafe in Manchester began in 1998 and periodically created short-term autonomous spaces including cafes.[42] The RampART Social Centre in Whitechapel, London, existed from May 2004 until October 2009, hosting meetings, screenings, performances, exhibitions and benefit gigs. As part of Occupy London the Bank of Ideas was occupied in Hackney.[43] The Spike Surplus Scheme was a venue and garden based in a former doss-house in Peckham, squatted from 1999 until 2009.

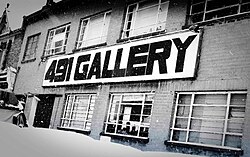

The 491 Gallery in Leytonstone, East London was a multidisciplinary art gallery.[44] Young artists who cannot afford to rent studio or gallery space, occupy abandoned buildings. Artist Matthew Stone from the !WOWOW! collective in South London states "I was obsessed with the idea of it, but also with getting to London and being part of a dynamic group of young people doing things."[45] Lyndhurst Way was squatted as a gallery from 2006 to 2007.

Temporary Autonomous Art, run by a group called Random Artists, is a series of squatted exhibitions which have been occurring since 2001.[46] Beginning in London, the events have also taken place in Brighton, Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Cardiff.[47]

Groups have also squatted land as community gardens. Two such London projects were the Kew Bridge Ecovillage and the Hounslow community land project. In Reading, a garden called Common Ground was opened in 2007.[48] It was then resquatted the following year as part of the April2008 days of action in support of autonomous spaces.

Da! collective is an art collective that received national attention when they squatted in a £6.25 million, 30-room, grade II-listed 1730s mansion owned by the Duke of Westminster in 2008. After being evicted, they moved to a £22.5m property nearby in Clarges Mews.[49]

Raven's Ait, an island in the River Thames, was occupied in 2009. The squatters declared their intention to set up an eco conference centre. The eviction of these squatters took place on 1 May by police using boats and specialist climbing teams.[50]

Legality

Common law

Historically, there is a common law right (known as "adverse possession") to claim ownership of a dwelling after continual unopposed occupation of land or property for a given period of several years or more, depending on the laws to a particular jurisdiction.[51]

UK laws allow for adverse possession claims range after 10 to 12 years, depending on if the land is unregistered. In practice, adverse possession can be difficult. For example, St Agnes Place in London had been occupied for 30 years until 29 November 2005, when Lambeth London Borough Council evicted the entire street.[52] The hermit Harry Hallowes won possession of a half-acre plot on Hampstead Heath in London in 2007.[53]

Criminal Law Act 1977

Section 6 of the Criminal Law Act 1977 covers the occupation of property. The Act was implemented to stop slum landlords forcibly evicting tenants (as was the case with the notorious London landlord Peter Rachman in the 1950s–1960s), and made "violence for securing entry" an offence. The law states:

- if "(a) there is someone present on those premises at the time who is opposed to the entry which the violence is intended to secure; and (b) the person using or threatening the violence knows that that is the case."[54] The law does not distinguish for this purpose between violence to persons or property (e.g. breaking a door down).

People who squatted in buildings would often put up a "Section 6" legal notice on the front door.[55] The notice stated there were people living in the property who claimed they had a legal right to be there. It warned anyone — even the actual owner of the property — who tried to enter the building without lawful permission that they would be committing an offence.

In September 2012, the law was changed making trespass in a residential building with the intention of permanently residing a criminal offence. Although a Section 6 warning still applies for non-residential buildings.

Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 introduced section 6.1(A) and other provisions were added, which override this and give the right of entry to "displaced residential occupiers", "protected intending occupiers" (someone who had intended to occupy the property, including some tenants, licensees and landlords who require the property for use), or someone acting on their behalf. These terms are defined in sections 12 and 12A. Such people may legally enter an occupied property even using force as the usual section 6 provision does not apply to them, and may require "any person who is on [their] premises as a trespasser" to leave. Failure to leave is a criminal offence under section 7 and removal may be enforced by police.

Civil Procedure Rules

In 2001, the Civil Procedure Rules introduced new processes for civil repossession of property and related processes, under section 55. These include a fast track process whereby the legally rightful occupier can obtain an interim possession order (IPO) in a civil court which will enable them to enter the premises at will. Any unlawful occupiers who refuse to leave after the granting of an IPO is committing a criminal offence[54] and can then be removed by police. However some of these processes may not be available unless used within 28 days of the time that the claimant knew of the unauthorised occupancy.

Criminal law refers to an "occupier"[7] or "trespasser",[56] and the Civil Procedure Rules part 55 refer to possession claims against "trespassers".

Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012

In March 2011, Mike Weatherley, Conservative MP for Hove, proposed an Early Day Motion calling for the criminalisation of squatting.[57] His campaign was backed by a series of articles in the Daily Telegraph in which Kenneth Clarke (the Secretary of Justice) and Grant Shapps (Minister of Housing) were reported to be backing the move.[58][59][60]

In response, Jenny Jones, Green mayoral candidate for London, said that squatting was an "excellent thing to do".[61] Campaigners relaunched Squatters' Action for Secure Homes (SQUASH) with a Parliamentary briefing chaired by John McDonnell MP. This formed a coalition between housing charities such as Shelter and Crisis, activists, lawyers and squatters.[62]

A total of 158 concerned academics, barristers and solicitors specialising in property law published a letter in The Guardian stating their concerns that "misleading" comments were being made in the mainstream media about squatting.[63] Mike Weatherley replied that "the self-proclaimed experts who signed the letter, sheep-like, have a huge vested interest when it comes to fees after all"[64] and Grant Shapps tweeted that "these lawyers are sadly out of touch".[65]

The Government opened a consultation entitled 'Options for dealing with squatters' on 13 July 2011, which ran until 5 October. It was "aimed at anyone affected by squatters or has experience of using the current law or procedures to get them evicted."[40] The pro-squatting campaign group SQUASH stated that there were "2,217 responses and over 90% of responses argued against taking any action on squatting."[66] Groups supporting a change in the law included the Crown Prosecution Service, Transport for London and the Property Litigation Association. Groups against a change included the Metropolitan Police, squatter networks, The Law Society, homelessness charities and the National Union of Students.

Kenneth Clarke then announced an amendment to the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Bill which would criminalise squatting in residential buildings.[67] In 1991, Clarke stated "There are no valid arguments in defence of squatting. It represents the seizure of another's property without consent."[68] John McDonnell commented that "by trying to sneak this amendment through the back door the government are attempting to bypass democracy."[69]

The amendment states that "the new offence will be committed where a person is in a residential building as a trespasser having entered it as a trespasser, knows or ought to know that he or she is a trespasser and is living in the building or intends to live there for any period."[40]

The change in legislation has been referred to by Mike Weatherley as "Weatherley's Law" [70] and came into force on 1 September 2012, making squatting in a residential building a criminal offence subject to arrest, fine and imprisonment.[71]

When the Government announced its plans to criminalise squatting, protests were launched across the UK and SQUASH (Squatters Action for Secure Homes) was reformed (it was first set up to fight previous plans regarding criminalisation in the mid-1990s) with a presentation at the House of Commons.[72] Squatters attempted to occupy the house of Justice Secretary Ken Clarke in September 2011.[73] The following month, twelve people were arrested outside the House of Commons whilst the criminalisation of squatting was being debated.[74]

Coronavirus pandemic

The Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) were updated due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the 117th practice direction update, 51Z stated that "All proceedings for possession brought under CPR Part 55 and all proceedings seeking to enforce an order for possession by a warrant or writ of possession are stayed for a period of 90 days from the date this direction comes into force".[75] The update was made on 27 March 2020.[76] A further update was then made on 20 April 2020, which announced that trespass and interim possession order (IPO) claims would not be included in the stay.[77]

After criminalisation

In September 2012, Alex Haigh was the first squatter imprisoned under the new law, receiving a sentence of 3 months after occupying a housing association property in London.[78] Two men were then found guilty of squatting above the Lamb Inn, in Romford.[79]

In November 2012, Conservative MPs called for the criminalisation of squatting in commercial buildings as well, due to the perceived increase in the squatting of business properties. These included the following pubs: the Cross Keys in Chelsea, the Tournament in Earls Court (both in London) and the Upper Bell Inn near Chatham, Kent.[80]

In February 2013, a homeless man named Daniel Gauntlett froze to death on the doorstep of an abandoned bungalow, in a case that has been linked with the new law.[81]

In November 2013, a squatter convicted under section 144 had his appeal upheld at Hove Crown Court.[82] The man had been arrested on 3 September 2012, in what was seen by The Guardian as the "first test of new legislation that makes squatting a criminal offence."[83] Two other squatters were also arrested and had previously had the charges against them dropped completely.[84]

An activist from Focus E15 was arrested on suspicion of squatting in 2015, when she was occupying a council flat in Stratford, London, in support of a mother who had been evicted.[85] The charges were later dropped less than 24 hours before the court hearing.[86]

A newsletter from SQUASH published in May 2016 states that there have been "at least 738 arrests, 326 prosecutions, 260 convictions and 11 people imprisoned for the offence, based on available information" since criminalisation.[87]

2010s

In recent years and despite the criminalisation of squatting in 2012, people have continued for different reasons, including homelessness, activism and partying. Many cities have social centres, often with their roots in the squatters movement. The Bloomsbury Social Centre was a short-lived social centre in central London. The Advisory Service for Squatters continues to offer practical advice and legal support.

Bristol

The perceived 2011 eviction of the Telepathic Heights squat in Stokes Croft in Bristol led to riots.[88]

One of Bristol's oldest squats, the Magpie, was evicted in 2016. The new owner plans to open a food market with pop-up restaurants in the space.[89]

Cardiff

As a result of the criminalisation of squatting in residential buildings, a group calling themselves The Gremlins in October 2012 resisted the eviction of the former Spin Bowling building in Cardiff from bailiffs and police. The group covered their faces with scarves and masks, posting on Bristol Indymedia claiming; "The state tries to make people homeless, anarchists have no sympathy for the state and its lackeys."[90] The protest was believed to be in response to the imprisonment of Alex Haigh, who was the first person jailed under the new Section 144 law in the UK.[91] The activists renamed the building the Gremlin Alley Social Centre and organised events.[92]

In November 2012, masked squatters moved into the Bute Dock Hotel in Cardiff Bay, which was owned by the nearby letting agents Keylet. They were seen on the roof and were believed to be from the group, after a post on the Gremlin Alley Twitter account. Managing director and chairman of the Association of Letting and Management Agents, Mr Vidler, said "It's distressing because I have items in there which are part of our business", concerned it would cost a lot of money to remove them.[93] Within a week they had left, after the owners took legal action, as it was being used for storage. Since the legal battle, Keylet plans to actively support tackling homelessness, believing "homelessness in Cardiff and the UK needs urgent attention." In a statement about the occupation,[94] the squatters said they intended to "reclaim this unoccupied space to re-open it for the use of the community."[95]

In 2013, the Gremlins squatted the former Rumpoles pub building opposite Cardiff prison and prepared for another eviction battle.[96]

London

Grow Heathrow is a squatted garden and part of the Transition Towns movement. It was raided by Metropolitan Police before the marriage of Prince William and Kate Middleton in April 2011, although the police denied any link to the wedding.[97] Social centres in Camberwell and Hackney were also raided.[98] Alleging unnecessary and illegal pre-emptive action was taken against them, the squatters requested a judicial review of the policing tactics.[99] Grow Heathrow has had a very long battle in the courts and faced several eviction attempts, most recently in February 2019, half the terrain was evicted.[100]

An activist group called Topple the Tyrants squatted a home belonging to Saif al-Islam, son of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, in March 2011.[101] It was an eight-bedroom mansion in Hampstead Garden Suburb, which had been listed for sale for €12.75 million when the 2011 Libyan civil war began.[102]

Another group called the Autonomous Nation of Anarchist Libertarians (ANAL) squatted a series of luxury mansions in order to bring attention to the housing crisis and the scandal of empty buildings. When they occupied the seven storey former Institute of Directors in Pall Mall, in March 2015, they claimed it was the seventeenth building in the area they had stayed in.[103] They occupied Admiralty Arch and were quickly evicted.[104] In January 2017, the group occupied a £15 million mansion at 102 Eaton Square in Belgravia and stated they would open a homeless shelter and community centre.[105] After being quickly evicted they moved to a £14m mansion nearby which was opposite Buckingham Palace.[106]

The political party Left Unity launched its manifesto at Ingestre Court in Soho in 2015.[107] National Secretary Kate Hudson said the choice of a squat as venue was to bring attention to the "terrible crisis" in UK housing.[108]

Largescale evictions of social housing have led to many local campaigns in London, which often involved occupation as a tactic to support tenants at risk of being decanted. These would include the Aylesbury estate in Elephant and Castle, Focus E15 in Newham and Sweets Way in Barnet.[109]

Focus E15 was formed when 29 young mothers living in Newham, east London were given notices of eviction from their hostel. The mothers refused to take rented accommodation in other cities such as Birmingham or Manchester and instead squatted flats on the mostly empty Carpenters Estate in 2014.[110]

Tenant eviction resistance at Sweets Way was bolstered by housing activists occupying empty flats in March 2015. The owner, Annington Property (controlled by a private equity fund run by Guy Hands), planned to evict and demolish all 142 residences and build 282 properties of 80% of which would be for private sale. In September the last council tenant Mostafa Aliverdipour (a 52-year-old wheelchair user), was forcibly evicted and at the same time over 100 squatters.[111]

Camelot Property Management is a company which manages empty property for owners and puts in users on lease contracts (with less rights than a rental contract) so as to prevent squatting. The empty Camelot headquarters in Shoreditch, east London, was itself squatted in September 2016. The building was renamed Camesquat.[112] After Camelot obtained an eviction order the squatters were evicted two months later.[113]

Free parties often happen in squatted venues in London, for example in Croydon,[114] Deptford,[115] Holborn,[3] Lambeth,[116] and Walthamstow.[117]

Manchester

The old Cornerhouse cinema in Manchester was squatted by the Loose Space collective in March 2018 and was evicted in October 2018. It had housed around 20 homeless people, who then moved on to another squat. The three rules established in the Cornerhouse were no hard drugs, no constant drinking, and no abuse in whatever form.[118] The collective had previously occupied the Hulme Hippodrome.[119]

Solving the worsening problem of homelessness in Manchester was a key pledge when Andy Burnham was elected mayor in 2017. He promised to end rough sleeping by 2020.[120] However, there were 40 squat evictions between 2015 and 2018 in Manchester and several homeless camps.[121]

In January 2018, there was a squatted homeless shelter in Manchester and the Loose Space collective were running a squat called the Wonder Inn.[118]

Elsewhere in England and Wales

A 2018 exhibition called 'Squatlife' at the St Albans Museum and Gallery showed photographs of squats and squatters in the city in the 1980s.[122] The photographer, Dave Kotula, had squatted in St Albans between 1986 and 1992. St Albans & Hertfordshire Architectural & Archaeological Society contributed another part of the exhibition which depicted the treatment of homeless people in the city over the centuries.[123]

See also

References

- ^ Reeve, Kesia (11 May 2011), Single people falling through cracks into years of homelessness, Crisis, archived from the original on 28 September 2011, retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ Carter, Helen (9 March 2011), Squatters launch protest at RSB branch in Manchester, London: Guardian, archived from the original on 7 March 2016, retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ a b Riot police tackle 'illegal' rave in High Holborn, BBC, 31 October 2010, archived from the original on 22 October 2019, retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ Squatters: Who are they and why do they squat? Archived 13 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC

- ^ "Squatting set to become a criminal offence". BBC News. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Ministry of Justice Circular No. 2012/04 – Offence of Squatting In a Residential Building" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ a b Criminal Law Act 1977 section 6

- ^ a b Monbiot, George (22 February 1995). "A Land Reform Manifesto". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Hammond, J. L.; Hammond, Barbara (1912). The Village Labourer 1760–1832. London: Longman. p. 31.

- ^ Mingay, G.E. (2014). Parliamentary Enclosure in England. London: Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-582-25725-2.

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric; Rudé, George (1973). Captain Swing: A Social History of the Great English Agricultural Uprising of 1830. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 16.

- ^ a b Harrison. The Common People. p. 135

- ^ Basket. Statutes at Large. Retrieved 10 November 2014 p. 664

- ^ Townsend. The Manual of Dates p. 252

- ^ Ed. Wates and Wolmar (1980)Squatting: The Real Story (Bay Leaf Books) ISBN 0-9507259-0-0

- ^ "Chalfont St Giles 1946". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Hinton, J. 'Self-help and Socialism The Squatters' Movement of 1946' in History Workshop Journal (1988) 25(1): 100–126.

- ^ a b c Webber, H. (2012). "A Domestic Rebellion: The Squatters' Movement of 1946" (PDF). Ex Historia. 4: 125–146. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ a b Bailey, Ron The Squatters (1973) Penguin:UK ISBN 0140523006

- ^ Martin, D. 'A Squat of Their Own' in Inside Housing August 2005

- ^ Police storm squat in Piccadilly News On This Day Archived 5 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine 21 September 1969

- ^ "Reading Room Only". 25 March 2011.

- ^ Faiers, Chris (1990). Eel Pie Dharma. Unfinished Monument Press. ISBN 0-920976-42-5.

- ^ "'Oldest squat' residents evicted". 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Advisory Service for Squatters". Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Glynn, S. 'East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing: A comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities' Archived 7 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine in Journal of Historical Geography 31 pp 528–545 (2005).

- ^ Kearns, K (1979). "Intraurban Squatting in London". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 69 (4): 589–598. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1979.tb01284.x.

- ^ Etoe, C Empty again, the squat attacked by bulldozers Camden New Journal 21 August 2003

- ^ Harris, John (30 October 2017). "Freedom for Frestonia: the London commune that cut loose from the UK". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Wates, Nick (1976). The Battle for Tolmers Square. ISBN 9780710084484.

- ^ Longstaffe-Gowan, T. (2012) The London Square: Gardens in the Midst of Town New Haven: Yale University Press

- ^ a b "We all live in Tolmers Square". Bartlett 100. Bartlett School of Planning. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "The muesli-maker who began in a squat". Guardian. 22 February 2014. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b Aufheben Kill or Chill – An analysis of the Opposition to the Criminal Justice Bill in Aufheben 4, 1995

- ^ Charlie Higson (October 2015). "Charlie Higson: my days squatting with Harry Enfield and Paul Whitehouse". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Wates, N. & Wolmar, C. (1983) Squatting the Real Story Bay Leaf:London.

- ^ "Another Space". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Burbridge, B. 'Political squatting: an arresting art' Archived 30 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine in The Guardian 28 September 2012

- ^ Fallon A Squatters are back, and upwardly mobile in The Independent on Sunday 12 October 2003

- ^ a b c "Options for dealing with squatters". Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Empty Homes Figures 2009 http://www.emptyhomes.com/usefulresources/stats/statistics.html Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Okasional Cafes". 20 December 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Paul Owen and Peter Walker (18 November 2011). "Occupy London takes over empty UBS bank". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ Figen Gunes (26 July 2012). "Community art space under threat". Waltham Forest Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ [1] The artists who are hot to squat... Hoby, Hermione, The Observer, April 2009

- ^ "About Random Artists". Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Macindoe, M. (2011). Out of Order: A Photographic Celebration of the Free Party Scene Bristol: Tangent Books. pp. 429–436. ISBN 978-190647743-1.

- ^ 'Creating Common Ground: A squatted community garden as a strategy for anti-capitalists' Archived 14 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine in Organise issue 69

- ^ Pidd, Helen. "Posh-squat artists take Mayfair mews". Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Didymus, M. 'Police evict squatters from Raven's Ait island' Archived 18 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine 1 May 2009

- ^ Adverse possession is defined as, "An open, notorious, exclusive and adverse possession for twenty years operates to convey a complete title...not only an interest in the land...but complete dominion over it." Sir William Blackstone (1759), Commentaries on the Laws of England, Volume 2, page 418.

- ^ "'Oldest squat' residents evicted". 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "Hampstead Heath hermit's land sells for £154k at auction". BBC News. 18 June 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Criminal Law Act 1977". Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ The Section 6 Legal Warning

- ^ Criminal Law Act 1977 section 12, and especially 12(3) and 12(6)

- ^ "Early day motion 1545". Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Howie, Michael (19 March 2011), Squatting to be made illegal, vows Clarke, London: Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 15 August 2017, retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ Romero, Roberta (24 May 2011), Coalition to make squatting a criminal offend, London: Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 11 August 2017, retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ Hutchison, Peter (18 March 2011), Squatters: how the law will change, London: Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 24 January 2019, retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ "Squatting is an excellent thing to do, says Green mayoral candidate". Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "New Coalition to be Launched in Parliament to SQUASH Anti-Squatting Legislation". Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ experts, 158 (25 September 2011), Media and politicians are misleading about law on squatters, London: Guardian, archived from the original on 24 August 2017, retrieved 8 November 2011

{{citation}}:|first=has numeric name (help) - ^ Lewis, Joseph (3 October 2011), Hove MP in dispute with 160 lawyers over squatting laws, News From Brighton, archived from the original on 7 October 2011, retrieved 8 November 2011

- ^ "Grant Schapps tweets". Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ "Campaign lobbies against rush to criminalise". Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Bill". Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Hansard HC Deb 15 October 1991 vol 196 cc151-65 Archived 27 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "'Government 'bypasses democracy' to sneak through anti-squatting laws'". Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Squatting set to become a criminal offence". BBC News. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ SQUASH SQUASH campaign launched Archived 27 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Malik, S. 'Squatting protests – as they happened' Archived 30 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine in The Guardian 15 September 2011

- ^ BBC News 'Police break up unauthorised London squatter protest' Archived 12 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine 1 November 2011.

- ^ "117th UPDATE – PRACTICE DIRECTION AMENDMENTS" (PDF). Judiciary.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "117th Practice Direction Update to the Civil Procedure Rules – Coronavirus Pandemic related". www.judiciary.uk. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "PRACTICE DIRECTION 51Z: STAY OF POSSESSION PROCEEDINGS, CORONAVIRUS". www.justice.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (27 September 2012). "First squatter jailed under new law". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Pair found guilty of squatting above historic Lamb Inn in Romford". London24. 14 November 2012.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (30 November 2012). "Criminalise squatting in commercial premises, say Tory MPs". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Hern, Alex (4 March 2013). "Death of homeless man blamed on anti-squatting laws". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Vowles, Neil (1 November 2013). "Celebrations at Hove squat trial failure". Brighton Argus. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Quinn, Ben (4 September 2012). "Police arrest three for squatting in Brighton property". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Two Brighton squat cases rejected in court". Brighton Argus. 24 April 2013. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Booth, Robert (14 March 2015). "Focus E15 housing activist arrested on suspicion of squatting". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Ramiro, Joana (12 May 2015). "Charge dropped for Focus E15 activist". Morning Star. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Squatting Statistics 2015 – version 2.0". SQUASH. May 2016. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Dutta, Kunal; Duff, Oliver (23 April 2011). "Police raid over 'petrol bomb plot' sparks Tesco riots". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Murray, Robin (8 November 2018). "A new food market with bar is opening in former squat 'The Magpie'". Bristol Post. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Gremlin Alley Eviction Resistance happening now". Bristol Indymedia. 4 October 2012. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Activists occupying former Cardiff bowling alley pledge to 'stay put'". Wales Online. 6 October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Gremlin Alley Social Centre – Resisting eviction since 4th October". Wordpress. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Masked squatters move into Bute Dock Hotel". Wales Online. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Communique from Bute Dock Hotel squatters, Cardiff". Bristol Indymedia. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Squatters forced to leave Bute Dock Hotel after estate agent Keylet launches legal action". Wales Online. 29 November 2012. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Malone, Sam (8 August 2013). "Masked squatters barricade themselves inside pub to avoid eviction". Wales Online. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Channel4 News Police: squat raids 'are not Royal Wedding-related' Archived 1 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine 28 April 2011

- ^ Royal wedding: Twenty arrested as squats raided across London Archived 6 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Daily Telegraph 28 April 2011

- ^ "'Royal wedding raids' judicial review". Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ "Eviction of Grow Heathrow squatters begins". BBC. London. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Esther Addley (9 March 2011). "Squatters take over Saif Gaddafi's London home | UK news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Kadhafi son's London home occupied by campaigners". RFI. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Amrani, Nadira (20 March 2015). "A Group of London Squatters Called ANAL Have Moved in Next to the Queen". Vice. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Amrani, Nadira (8 April 2015). "Inside the Brief Occupation of the Luxury Squat Opposite Buckingham Palace". Vice. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ England, Charlotte (29 January 2017). "Anarchist squatters take over £15m London mansion owned by Russian billionaire". Independent. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Diane (24 February 2017). "Serial squatters face eviction from £14m London mansion". Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Chakelian, Anoosh (31 March 2015). "A manifesto launch with a difference: Left Unity attacks Labour from a Soho squat". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Eardley, Nick (31 March 2015). "Election 2015: Ken Loach launches 'radical' Left Unity manifesto". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Cosslett, Rhiannon Lucy (22 August 2015). "Generation rent v the landlords: 'They can't evict millions of us'". Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Amara, Pavan (28 September 2015). "E15 'occupation': We shall not be moved, say Stratford single parents fighting eviction after occupying empty homes". Independent. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Booth, Robert (24 September 2015). "Sweets Way standoff ends as last remaining council tenant evicted". Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Diane (27 September 2016). "London protesters occupy former HQ of property management firm". Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Diane (1 December 2016). "Squatters evicted from building of company that works to stop squatting". Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Croydon death rave: No officers disciplined". BBC. 12 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Police attacked while stopping illegal rave in Deptford". BBC. 21 January 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Rave crowd clashes with riot police in Lambeth". BBC. 1 November 2015. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Police injured after missiles thrown at Walthamstow rave". BBC. 3 July 2016. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b Cashin, Declan (30 October 2018). "What everyday life in a squat is like". BBC. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Abbit, Beth (2 September 2017). "Inside Hulme Hippodrome: How squatters have given it a new lease of life". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Perraudin, Frances (9 May 2017). "Andy Burnham launches plan to drive down homelessness in Manchester". Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Broomfield, Matt (16 January 2018). "The squatters and rough sleepers taking up the fight against homelessness in Manchester". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Suslak, Anne (10 April 2018). "St Albans Museum project will focus on homelessness in the district". The Herts Advertiser. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ "St Albans squat photos inspire homeless exhibition at new museum". BBC. 14 July 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

Further reading

- Bailey, R., Conn, M. & Mahony, T. (1969) Evicted: The Story of the Illegal Evictions of Squatters in Redbridge London Squatters Campaign: London.

- Bailey, R. (1973) The Squatters Penguin: London. ISBN 0140523006.

- Hinton, J. 'Self-help and Socialism The Squatters' Movement of 1946' in History Workshop Journal (1988) 25(1) pp. 100–126.

- Lessing, D. (1985) The Good Terrorist Jonathan Cape: London. ISBN 0-224-02323-3

- Townsend, George H. (1862). The Manual of Dates: A Dictionary of Reference etc. London: Routledge, Warne and Routledge.

- Wates, N. & Wolmar, C. (1983) Squatting the Real Story Bay Leaf: London.

- Wates, N. (1976) The Battle for Tolmers Square Routledge: London.

- Webber, H. 'A Domestic Rebellion: The Squatters' Movement of 1946' in Ex Historia (2012) 4 pp. 125–146.

External links

- UK Squatting Archive

- Wasteland (UK) – Documentary about squatting by Will Wright

- What's this place? (2008) – A booklet with stories from radical social centres in the United Kingdom and Ireland