Sri Lankan independence movement

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

| History of Sri Lanka | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronicles | ||||||||||||||||

| Periods | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| By Topic | ||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

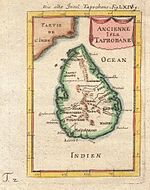

The Sri Lankan independence movement was a peaceful political movement which was aimed at achieving independence and self-rule for the country of Sri Lanka, then British Ceylon, from the British Empire. The switch of powers was generally known as peaceful transfer of power from the British administration to Ceylon representatives, a phrase that implies considerable continuity with a colonial era that lasted 400 years.[1] It was initiated around the turn of the 20th century and led mostly by the educated middle class. It succeeded when, on 4 February 1948, Ceylon was granted independence as the Dominion of Ceylon. Dominion status within the British Commonwealth was retained for the next 24 years until 22 May 1972 when it became a republic and was renamed the Republic of Sri Lanka.

British colonial rule

[edit]The British were dominant in Asia after the Battle of Assaye; following the Battle of Waterloo, the British Empire became more influential.[1] Its prestige was only briefly dented by setbacks in India, Afghanistan and South Africa. It was virtually unchallenged until 1914. The British were very powerful during their rule in Sri Lanka and left more of a lasting impact than any other power.[1]

The formation of the Batavian Republic in the Netherlands as an ally and of the French Directory, led to a British attack on Ceylon in 1795 as part of Britain's war against the French Republic. The Kandyan Kingdom collaborated with the British expeditionary forces against the Dutch, as it had with the Dutch against the Portuguese.

Once the Dutch had been evicted, their sovereignty ceded by the Treaty of Amiens and subsequent revolts in the low-country suppressed, the British began planning to capture the Kandyan Kingdom. The 1803 and 1804 invasions of the Kandyan provinces in the 1st Kandyan War were defeated by the Kandyan Sinhalese forces. In 1815, the British fomented a revolt by the Kandyan Sinhalese aristocracy against the last Kandyan monarch and marched into uplands to depose him in the 2nd Kandyan War.

The struggle against the colonial power began in 1817 with the Uva Rebellion when the same aristocracy rose against British rule in a rebellion in which their villagers participated. They were defeated by the British. An attempt at rebellion sparked again briefly in 1830. The Kandy and Sinhalese peasantry were stripped of their lands by the Crown Lands (Encroachments) Ordinance No. 12 of 1840 (sometimes called the Crown Lands Ordinance or the Waste Lands Ordinance),[2] a modern enclosure movement and reduced to penury.

In 1848 the abortive Matale Rebellion, led by Hennedige Francisco Fernando (Puran Appu) and Gongalegoda Banda was the first transitional step towards abandoning the feudal form of revolt, being fundamentally a peasant revolt. The masses were without the leadership of their native King (deposed in 1815) or their chiefs (either crushed after the Uva Rebellion or collaborating with the colonial power). The leadership passed for the first time in the Kandyan provinces into the hands of ordinary people, non-aristocrats. The leaders were yeomen-artisans, resembling the Levellers in England's Civil War period and mechanics such as Paul Revere and Tom Paine who were at the heart of the American Revolution. However, in the words of Colvin R. de Silva, 'it had leaders but no leadership. The old feudalists were crushed and powerless. No new class capable of leading the struggle and heading it towards power had yet arisen.'

Plantation economy

[edit]Agriculture was the main source of revenue for the country and foreign exchanges. The land in Sri Lanka is very important because it has led to many different wars among different countries.[3] In the 1830s, coffee was introduced into Sri Lanka, a crop which flourishes in high altitudes, and grown on the land taken from the peasants. The principal impetus to this development of capitalist production in Sri Lanka was the decline in coffee production in the West Indies, following the abolition of slavery there.

However, the dispossessed peasantry was not employed on the plantations: The Kandyan Sinhalese villagers refused to abandon their traditional subsistence holdings and become wage-workers in the harsh conditions that prevailed on these new estates, despite the pressure exerted by the colonial government. The British therefore had to draw on its reserve army of labour in India, to man the plantations in its lucrative new colony to the south. Through the Indian indenture system, hundreds of thousands of Tamil "coolies" from southern India were transported into Sri Lanka to work on European-owned cash crop plantations.[4]

The coffee economy collapsed in the 1870s when coffee blight ravaged the plantations, but the economic system it had created survived intact into the era of its successor, tea, which was introduced on a wide scale from 1880 onwards. Tea was more capital-intensive and needed a higher volume of initial investment to be processed so that individual estate-owners were now supplanted by large English consolidated companies based either in London ('sterling firms') or Colombo ('rupee firms'). Monoculture was thus increasingly capped by monopoly within the plantation economy. The pattern thus created in the 19th century remained in existence down to 1972. The only significant modification to the colonial economy was the addition of a rubber sector in the mid-country areas.

The Buddhist resurgence and the 1915 riot

[edit]A new body of urban capitalists was growing in the low country, around transport, shop-keeping, distillery, plantation, and wood-work industries. These entrepreneurs were from many castes and they strongly resented the historically unprecedented and unbuddhistic practice of 'caste discrimination' adopted by the Siam Nikaya in 1764, just 10 years after it had been established by a Thai monk. Around 1800 they organised the Amarapura Nikaya, which became hegemonic in the low-country by the mid-19th century.

Buddhism was enforced by kings and priests because they belonged to the Brahmin caste which allowed them to have the power to push what religion they wanted to practice. Buddhism practiced among higher castes (Brahmins) was further enforced by kings/ priest power, and their power increased and carried into the newly settled land.[5] Since the higher caste individuals and those in power were enforcing Buddhism, it eventually became the established religion among the Sihlanese communities. It became very popular among all castes and practiced all over and in different land (areas). There was a practice that was known as Asoka in the Sihlanese kingdom and it is thought that Buddhism has many aspects that stemmed from Asoka. Similar to Asoka (Practice among the Sinhalese) "Such establishment of Buddhism in a country was evidently a departure in the history of that religion and seems to have been an innovation of Asoka".[5]

The British attempt at giving a Protestant Christian education to the young men of the commercial classes backfired, as they transformed the Buddhism practiced in Sri Lanka into something resembling the non-conformist Protestant model. A series of debates against clergymen of the Methodist and the Anglican church was organised, culminating in the 'defeat' of the latter at Panadura by modern logical argument. The Buddhist revival was aided by the Theosophists, led by American Col. Henry Steel Olcott, who helped establish Buddhist schools such as Ananda College, Colombo; Dharmaraja College, Kandy; Maliyadeva College, Kurunegala; Mahinda College, Galle; and Musaeus College, Colombo; at the same time injecting more modern secular western ideas into the 'Protestant' Buddhist thought-stream.

Dharmapala, 1915 and the Ceylon National Congress

[edit]Sinhala Buddhist Revivalists such as Anagarika Dharmapala started linking 'Protestant' Buddhism to Sinhalese-ness, creating a Sinhala-Buddhist consciousness, linked to the temperance movement. This cut across the old barriers of caste and was the beginning of a pan-Sinhala Buddhist identity. It appealed in particular to small businessmen and yeomen, who now began to take centre stage against the Mudaliyars, an anglicised class of new elites created by the British rulers. The collaborationist compradore elements of the elite, led by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, F.R. Senanayake and D.S. Senanayake succeeded the populists led by Dharmapala from the leadership of the temperance movement.

A jolt was given to the British aura of invincibility by the German cruiser Emden, which attacked the seaport of Penang in Malaya, sinking a Russian cruiser, bombarded Madras and sailed unimpeded down the eastern coast of British Ceylon. Such was its impact that, in Sri Lanka to this day, 'Emden' is the bogeyman that mothers scare their children with, and the term is still used to refer to a particularly obnoxious person. In a panic, the colonial authorities jailed a Boer wildlife official, H. H. Engelbrecht, after accusing him falsely of having supplied meat to the cruiser. Another jolt to the aura of British invincibility was their defeat in the Gallipoli campaign in 1915.[6]

In 1915 commercial-ethnic rivalry erupted into a riot in the Colombo against the Muslims, with Christians participating as much as Buddhists. The British colonial authorities reacted heavy-handedly, as the riot was also directed against them. Dharmapala had his legs broken and was confined to Jaffna; his brother died there. Captain D. E. Henry Pedris, a militia commander was shot for mutiny. Inspector-General of Police Herbert Dowbiggin became notorious for his methods. Hundreds of Sinhalese Buddhists were arrested by the British colonial government during the Riots of 1915. Those imprisoned without charges included future leaders of the independence movement; F.R. Senanayake, D. S. Senanayake, Anagarika Dharmapala, Dr C A Hewavitarne, Arthur V Dias, H. M. Amarasuriya, Dr. W. A. de Silva, Baron Jayatilaka, Edwin Wijeyeratne, A. E. Goonesinghe, John Silva, Piyadasa Sirisena and others.[7][8][9]

Sir James Peiris initiated and drafted a secret memorandum with the support of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan and E. W. Perera braved mine and submarine-infested seas (as well as the Police) to carry it in the soles of his shoes to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, pleading for the repeal of martial law and describing the actions committed by the Police led by Dowbiggin during the riots.[10] The British government ordered the release of the leaders who were in detention. Several high officials were transferred. A new Governor, Sir John Anderson was sent to replace Sir Robert Chalmers with instructions to inquire and report to His Majesty's Government. Newspapers such as The Ceylon Morning Leader played a vital role to mold public opinion.[11]

In 1919 the Ceylon National Congress (CNC) was founded to agitate for greater autonomy. It did not seek independence, however, representing the comprador elite which opposed Dharmapala. This same elite vigorously opposed the grant of universal suffrage by the Donoughmore Constitutional Commission.

Dharmapala was hounded out of the country by a press campaign by the Lake House group of the press baron D. R. Wijewardena. His mantle fell on the next generation, epitomised by the likes of Walisinghe Harischandra, Gunapala Malalasekera, and L.H. Mettananda, who were radicalised by Dharmapala's words.

The Youth Leagues and the struggle for independence

[edit]The young people who stepped into the shoes of Dharmapala organised themselves into Youth Leagues, seeking independence and justice for Sri Lanka. The first moves came from the Young Lanka League led by A. E. Gunasinha, C. H. Z. Fernando, EAP Wijerathne and AP Thambayah. In 1924 The Jaffna Students' Congress, later renamed the Jaffna Youth Congress (JYC) was founded. Influenced by the Indian Independence movement, it was secular and committed to Poorana Swaraj (Complete Self-Rule), national unity, and the eradication of inequalities imposed by caste. In 1927, the JYC invited the Indian independence movement leader Mahatma Gandhi to visit Jaffna. The JYC led a successful boycott of the first State Council elections in Jaffna in 1931, arguing that the Donoughmore reforms did not concede enough self-government. [1]

In the 1930s the Youth Leagues were formed in the South, around a core of intellectuals who had returned from education in Britain, influenced by leftist ideals. The Ministers of the CNC petitioned the colonial government to increase their powers, instead of demanding independence, or even dominion status. They were forced to withdraw their 'Ministers' Memorandum' after a vigorous campaign by the Youth Leagues. [2][3]

The South Colombo Youth League became involved in a strike at the Wellawatte Spinning and weaving mills. It published an irregular journal in Sinhala, Kamkaruwa (The Worker).

Suriya-Mal movement

[edit]In protest against the proceeds of poppy sales on Armistice Day (11 November) being used for the benefit of the British ex-servicemen to the detriment of Sri Lankan ex-servicemen, one of the latter, Aelian Perera, had started a rival sale of Suriya (Portia tree) flowers on this day, the proceeds of which were devoted to helping needy Ceylonese ex-servicemen.[citation needed]

In 1933 a British teacher Doreen Young Wickremasinghe, wrote an article, The Battle of the Flowers which appeared in the Ceylon Daily News and criticised the practice of forcing Sri Lankan schoolchildren to purchase poppies to help British veterans at the expense of their own, which caused her to be vilified by her compatriots.

The South Colombo Youth League now got involved in the Suriya-Mal Movement and revived it on a new anti-imperialist and anti-war basis. Yearly until the Second World War, young men and women sold Suriya flowers on the streets on Armistice Day in competition with the Poppy sellers. The purchasers of the Suriya Mal were generally from the poorer sections of society and the funds collected were not large. But the movement provided a rallying point for the anti-imperialist minded youth of the time. An attempt was made by the British colonial authorities to curb the movement's effectiveness through the 'Street Collection Regulation Ordinance'.

Doreen Young was elected the first president of the Suriya Mal movement at a meeting held at the residence of Wilmot Perera in Horana. Terence de Zilva and Robin Ratnam were elected Joint Secretaries, and Roy de Mel Treasurer.

Malaria epidemic and floods

[edit]There had been a drought in 1934 which caused a shortage of rice, estimated at 3 million bushels. From October on there were floods, followed by a malaria epidemic in 1934–35, during which 1,000,000 people were affected and at least 125,000 died. The Suriya-Mal Movement was honed by volunteer work among the poor during the malaria epidemic and the floods. The volunteers found that there was widespread malnutrition, which was aggravated by the shortage of rice, and which reduced resistance to the disease. They helped fight the epidemic by making pills of 'Marmite' yeast extract. Philip Gunawardena and N. M. Perera came to be known as Avissawelle Pilippuwa (Philip from Avissawella) and Parippuwa Mahathaya ('Mr. Dhal') because of the lentils he distributed as dry rations to the people affected in those days.

As Sybil described in Forward: The Progressive Weekly many years later: 'Work in connection with malaria relief was an eye-opener to many of these people who were just getting to know the peasant masses. The poverty was incredible, the overcrowding even more so, fifteen, twenty or more people crammed into tiny huts, dying like flies. This was what colonial exploitation meant: worse than the worst that prevailed in Britain when Marx and Engels analysed the conditions of the working classes. This was what had to be fought.' [4]

The Lanka Sama Samaja Party is formed

[edit]The Marxist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), which grew out of the Youth Leagues in 1935, was the first party to demand independence.[5] The first manifesto of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party declared that its aims were the achievement of complete national independence, the nationalisation of the means of production, distribution, and exchange, and the abolition of inequalities arising from differences of race, caste, creed or gender.

Its deputies in the State Council after the 1936 general election, N. M. Perera and Philip Gunawardena and the other leaders Leslie Goonewardene and Colvin R. de Silva were aided in this struggle by not quite so radical members like Don Alwin Rajapaksa of Ruhuna and K. Natesa Iyer of the Indian Tamils. Others who supported them from time to time were George E. de Silva of Kandy, B. H. Aluwihare of Matale, D. P. Jayasuriya of Gampaha, A. Ratnayake of Dumbara and Susantha de Fonseka, Deputy Speaker. They also demanded the replacement of English as the official language by Sinhala and Tamil. In November 1936, motions that 'in the Municipal and Police Courts of the Island the proceedings should be in the vernacular' and that 'entries in police stations should be recorded in the language in which they are originally stated' were passed by the State Council and referred to the Legal Secretary, but nothing was done about these matters and English continued to be the language of the rule until 1956.

Fraternal relations were established between the LSSP and the Congress Socialist Party (CSP) of India and an LSSP delegation attended the Faizpur Sessions of the Indian National Congress in 1936. In April 1937 Kamaladevi Chattopadyaya, a leader of the CSP addressed a large number of meetings in various parts of the country on a national tour organised by the LSSP. This helped to establish the indivisibility of the fights for the independence of Sri Lanka and India. In Jaffna, where Kamaladevi also spoke, the left movement found consistent and loyal supporters from among one-time members of the JYC.

Bracegirdle

[edit]On 28 November 1936, at a meeting in Colombo, the president of the LSSP, Dr. Inusha de Silva, introduced Mark Anthony Bracegirdle, a British/Australian former planter saying: 'This is the first time a white comrade has ever attended a party meeting held at a street corner.' He made his first public speech in Sri Lanka, warning that the capitalists were trying to split the workers of Sri Lanka and put one against the other. He took an active part in organising a public meeting called by the LSSP on Galle Face Green in Colombo on 10 January 1937 to celebrate Sir Herbert Dowbiggin's departure from the island and to protest against the actions of the police during his tenure as Inspector General. In March, he was co-opted to serve on the executive committee.

He was employed by Natesa Iyer, Member of the State Council for the Hatton constituency, to 'organise an Estate Labour Federation in Nawalapitiya or Hatton, with an idea that he may be a proper candidate to be the future Secretary of the Labour Federation.' [6]

On 3 April, at a meeting at Nawalapitiya attended by two thousand estate workers, at which Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya spoke, Dr. N. M. Perera said: 'Comrades, I have an announcement to make. You know we have a white comrade (applause) .... He has generously consented to address you. I call upon Comrade Bracegirdle to address you.' Bracegirdle rose to speak amid tumultuous applause and shouts of 'Samy, Samy' (master, master).

The authorities were on hand to note his speech:

'the most noteworthy feature of this meeting ... was the presence of Bracegirdle and his attack on the planters. He claimed unrivaled knowledge of the misdeeds of the planters and promised scandalous exposures. His delivery, facial appearance, his posture were all very threatening ... Every sentence was punctuated with cries of samy, samy from the labourers. Labourers were heard to remark that Mr. Bracegirdle has correctly said that they should not allow planters to break labour laws and they must in future not take things lying down.' (T. Perera, The Bracegirdle Saga: 60 Years After, 'What Next', No 5 1997.)[7]

The British planters were angry that their prestige was being harmed by a fellow white man. They prevailed upon the British Colonial Governor Sir Reginald Stubbs to deport him. Bracegirdle was served with the order of deportation on 22 April and given 48 hours to leave on the SS Mooltan, on which a passage had been booked for him by the Government.

The LSSP with Bracegirdle's assent decided that the order should be defied. Bracegirdle went into hiding and the Colonial Government began an unsuccessful manhunt. LSSP started a campaign to defend him. At that year's May Day rally at Price Park, placards declaring 'We want Bracegirdle – Deport Stubbs' were displayed, and a resolution was passed condemning Stubbs, demanding his removal and the withdrawal of the deportation order.

On 5 May, in the State Council, NM Perera and Philip Gunawardena moved a vote of censure on the Governor for having ordered the deportation of Bracegirdle without the advice of the acting Home Minister. Even the Board of Ministers had started feeling the heat of public opinion and the vote was passed by 34 votes to 7.

On the same day, there was a 50,000-strong rally at Galle Face Green, which was presided over by Colvin R de Silva and addressed by Dr. N.M. Perera, Philip Gunawardena, Leslie Goonewardene, A. E. Goonesinha, George E. de Silva, D. M. Rajapakse, Siripala Samarakkody, Vernon Gunasekera, Handy Perimbanayagam, Mrs. K. Natesa Iyer and S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. Bracegirdle made a dramatic appearance on the platform at this rally, but the police were powerless to arrest him.

However, the police managed to arrest him a couple of days later at the Hulftsdorp residence of Vernon Gunasekera, the Secretary of the LSSP. However, the necessary legal preparations had been made. A writ of habeas corpus was served and the case was called before a bench of three Supreme Court judges presided over by Chief Justice Sir Sidney Abrahams. H. V. Perera, the county's leading civil lawyer, volunteered his services free on behalf of Bracegirdle; he was made a Queen's Counsel (QC) on the day that Bracegirdle appeared in court. On 18 May order was made that he could not be deported for exercising his right to free speech, and Bracegirdle was a free man.

Dasa Laksha pethsama

[edit]In 1954, upon hearing of the Royal tour of Ceylon by the Queen Elizabeth II, C. A. S Marikar and Henry Abeywickrema gained 1 million signatures of the public for a petition against the upcoming visit. His opposition was on the basis that if Ceylon was truly independent why should it invite the monarchy to tour the country, although under the Constitution of Ceylon, Queen Elizabeth II was the country's formal head of state, as the Monarch of Ceylon. His objective was to expose to the villages in Sri Lanka the Independence gained in 1948 was a name sake one and was only an alternate for of power management. The government in order to avoid any potential disruptions placed Marikar and Abeywickrama under house arrest for the duration of the Royal tour.[

Second World War

[edit]After the outbreak of the Second World War, the independence agitators turned to opposition to the Ministers' support for the British war effort. The Ministers brought motions gifting the Sri Lankan taxpayers' money to the British war machine, which were opposed by the pro-independence members of the state council. There was considerable opposition to the war in Sri Lanka, particularly among the workers and the nationalists, many of the latter of whom hoped for a German victory. Among Buddhists, there was disgust that Buddhist monks of German origin were interned as 'enemy aliens' whereas Italian and German Roman Catholic priests were not.

Two members of the Governing Party, Junius Richard Jayawardene and Dudley Senanayake, held discussions with the Japanese with a view to collaboration to oust the British.

Estate strike wave

[edit]Starting in November 1939 and during the first half of 1940 there was a wave of spontaneous strikes in the British-owned plantations, basically aimed at winning the right of organisation. There were two main plantation unions, Iyer's Ceylon Indian Congress and the All-Ceylon Estate Workers Union (later the Lanka Estate Workers Union, LEWU) led by the Samasamajists.

In the Central Province the strike wave reached its zenith in the Mool Oya Estate strike, which was led by Samasamajists including Veluchamy, Secretary of the Estate Workers Union. In this strike, on 19 January 1940, the worker Govindan was shot and killed by the police. As a result of agitation both within the State Council and outside, the Government was compelled to appoint a Commission of Inquiry. Colvin R. de Silva appeared for the widow of Govindan and exposed the combined role of the police and employers in the white plantation raj.

After Mool Oya, the strike wave spread southward towards Uva, and the strikes became more prolonged and the workers began more and more to seek the militant leadership of the Sama samajists. In Uva, Samasamajists including Willie Jayatilleke, Edmund Samarakkody and V. Sittampalam were in the leadership. The plantation-raj got the Badulla Magistrate to issue a ban on meetings. N. M. Perera broke the ban and addressed a large meeting in Badulla on 12 May, and the police were powerless to act. At Wewessa Estate the workers set up an elected council and the Superintendent agreed to act in consultation with the Workers' Council. An armed police party that went to restore 'law and order' was disarmed by the workers.

The strike wave was finally beaten back by a wave of violence by the police, aided by floods which cut Uva off from the rest of the country for over a week. But the colonial authorities realised that the independence struggle had become too powerful to ignore.

Underground struggle

[edit]After Dunkirk, the British colonial authorities reacted in panic (as revealed in secret files released many decades later) and N. M. Perera, Philip Gunawardena and Colvin R. de Silva were arrested on 18 June 1940 and Edmund Samarakkody on 19 June. The LSSP press was raided and sealed. Regulations were promulgated which made open party work practically impossible.

However, the experience gained in hiding Bracegirdle now paid off. The cover organisation of the LSSP, of which Doric de Souza and Reggie Senanayake were in charge, had been active for some months. Detention orders had been issued on Leslie Goonewardene but he evaded arrest and went underground. The LSSP was involved in a strike wave which commenced in May 1941 affecting the workers of the Colombo Harbour, Granaries, Wellawatta Mills, Gas Company, Colombo Municipality and the Fort Mt-Lavinia bus route.

With Japan's entry into the war, and especially after the fall of Singapore, Sri Lanka became a front-line British base against the Japanese. On 5 April 1942, The Japanese Navy bombed Colombo. That evening, in the confusion following the attack, the LSSP leaders were able to escape, with the help of one of their guards. Several of them fled to India, where they participated in the independence movement there. However, a sizeable contingent remained, led by Robert Gunawardena, Philip's brother. In 1942 and 1944 the LSSP gave leadership to several other strikes and in the process was able to capture the leadership of Government workers’ unions in Colombo.

Cocos Islands mutiny

[edit]The fall of Singapore and the subsequent defeat and sinking of the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse, punctured the propaganda of British invincibility. The credibility & prestige of the British was further damaged by the sinking of the aircraft carrier Hermes and the cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire off Sri Lanka in early April 1942; accompanied at the same time by the virtually unopposed bombing of mainly the British colonial bases in the island and bombardment of Madras (Chennai). Such was the panic amongst the British in Sri Lanka that a large turtle which came ashore was reported by an Australian unit as a number of Japanese amphibious vehicles.

The Ceylon Garrison Artillery on Horsburgh Island in the Cocos Islands mutinied on the night of 8/9 May, intending to hand the islands over to the Japanese. The mutiny took place partly because of the agitation by the LSSP. The mutiny was suppressed and three of the mutineers were the only British Commonwealth troops to be executed for mutiny during the Second World War. [8] Gratien Fernando, the leader of the mutiny, was defiant to the end.

No Sri Lankan combat regiment was deployed by the British in a combat situation after the Cocos Islands Mutiny. The defenses of Sri Lanka were beefed up to three British army divisions because the island was strategically important, holding almost all the British Empire's resources of rubber. Rationing was instituted so that Sri Lankans were comparatively better fed than their Indian neighbours, in order to prevent disaffection among the natives.

Lanka Regiment and Hikari Kikan

[edit]Sinhalese and Tamils in Singapore and Malaysia formed the 'Lanka Regiment' of the Indian National Army, directly under Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. A plan was made to transport them to British Ceylon by submarine, to begin an independence uprising against colonial rule, but this was aborted.

The Hikari Kikan, the Japanese liaison office for South Asia, recruited Sinhalese, Tamils, Indians and other south Asians domiciled in Malaya and Singapore for spying missions against the Allies. Four of them were to be landed by submarine at Kirinda, on the south coast of Sri Lanka, to operate a secret radio transmitter to report on South East Asia Command activities. However, they were dropped in error on the Tamil Nadu coast, where they were caught and executed.[9]

Free Lanka Bill

[edit]Public opposition to British colonial rule continued to grow. Among the elite there was irritation at the colour-bar practised by the leading clubs. Sir Oliver Ernest Goonetilleke, the Civil Defence Commissioner complained that the British commander of Ceylon, Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton called him a 'black bastard'.

The CNC agreed to accept the Communists, who had been expelled by the Trotskyists in the Sama Samaja Party but who now supported the war effort. At its 25th annual conference, the CNC resolved to demand 'a complete freedom after war'. The leader of the house and Minister of Agriculture and Lands Don Stephen Senanayake left the CNC on the issue of independence, disagreeing with the revised aim of 'the achieving of freedom'.[9]

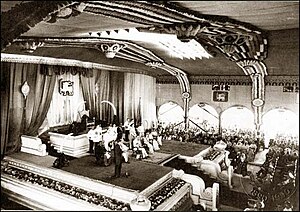

In November 1944, Sir Susantha de Fonseka, the State Council member for Panadura, moved a motion in the State Council calling for a dominion-type constitution for a Free Lanka. Subsequently, the "Free Lanka Bill" was introduced in the State Council, on 19 January 1945.

At annual session of the Ceylon National Congress was held on 27–28 January 1945 its president, George E. de Silva, said, "Today we stand pledged to strive for freedom. Nothing less than that can be accepted."[citation needed]

The Congress resolved, "Whereas the decision of the State Council 'to frame a Constitution of the Dominion type for a Free Lanka', falls short of the full national right for freedom, nevertheless, this Congress instructs its members in the State Council to support the Bill providing 'a new constitution for a Free Lanka' as an advance in our struggle for freedom..."

A second reading of the Free Lanka Bill was moved and passed without division on in February. The Bill brought up for a third reading, with amendment, on 22 March. G A Wille, a British-nominated member, moved that ‘The Bill be read the third time six months hence’, which was defeated by 40 to 7.[citation needed]

Post-war unrest

[edit]With the conclusion of the war against Germany, public pressure for the release of the detenus increased. On 30 May 1945 A. P. Jayasuriya moved a resolution in the State Council that the detained independence agitators be released unconditionally. This was passed, opposed only by two British nominated members. However, the detainees were only released on 24 June, after a two-day hunger strike. The released prisoners were hailed as heroes and given receptions throughout the country. The Left had emerged stronger than before the war, having earned tremendous prestige.

The oppression during the war years had kept unrest under control but, with the relaxation of wartime restrictions, there was an eruption of popular anger. From September onwards, there was a wave of strikes in Colombo, on the tramways and in the harbour. In November the LSSP-led All Ceylon United Motor Workers' Union launched an island-wide bus strike, which was successful in spite of the arrest of N. M. Perera, Philip Gunawardena and other leaders.

The All-Ceylon Peasant Congress took action on the compulsory collection of rice by the government at 8 rupees per bushel. In some areas the farmers refused to give their rice to the Government and hundreds were charged in the courts. In 1946 the Congress organised a march on the State Council, which compelled the Ministers to drop the system of compulsory collection.

In October 1946 a strike of Government workers, including those in the railway, extended to the harbour, the gas company, and became a general strike. The authorities at first refused to negotiate, but finally the Acting Governor agreed to meet a deputation of the Government Workers' Trade Union Federation. The adviser to the deputation, N. M. Perera was arrested by the police, but the workers refused to come to a settlement in his absence. In the end Perera was released and a settlement was reached.

However, some of the promises made by the Acting Governor were not honoured, and a second general strike broke out in May–June 1947. The Ceylon Defence Force was recalled from leave in order to aid the police in crushing this upsurge. V. Kandasamy of the Government Clerical Service Union was shot dead at Dematagoda, on the way to Kolonnawa after a strike meeting at Hyde Park, Colombo, when the police repeatedly fired on the crowd. The suppression was successful in breaking the strike. However, it was set in stone for the British authorities that their position in the country was untenable. The Bombay Mutiny and other signs of unrest in the armed forces of India had already caused the British to start their retreat from that country.

General Election 1947

[edit]D.S. Senanayake formed the United National Party (UNP) in 1946 [9], when a new constitution was agreed on. At the elections of 1947, the UNP won a minority of the seats in Parliament, but cobbled together a coalition with the Sinhala Maha Sabha of S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and the Tamil Congress of G. G. Ponnambalam. It was to this government that the British prepared to hand over power.

See also

[edit]- National Heroes of Sri Lanka

- Sri Lankan independence activist

- Independence Commemoration Hall (Sri Lanka)

Sri Lanka portal

Sri Lanka portal

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Brass, Paul (18 June 2010). Routledge Handbook of South Asian Politics : India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. ISBN 9780415434294.

- ^ Ellman, A. O.; Ratnaweera, D. De S.; Silva, K.T.; Wickremasinghe, G. (January 1976). Land Settlement in Sri Lanka 1840-1975: A Review of the Major Writings on the Subject (PDF). Colombo, Sri Lanka: Agrarian Research and Training Institute. p. 16. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Winslow, Deborah (2 September 2004). Economy, Culture, and Civil War in Sri Lanka. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253344205.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, V. "Indian origin in Sri Lanka:Their plight and struggle for survival". Proceedings of First International Conference & Gathering of Elders. International Center for Cultural Studies, USA. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ a b Arasaratnam, Sinnappah (1964). Ceylon. Prentice-Hall.

- ^ K. M. de Silva, University of Ceylon History of Ceylon, p. 225

- ^ Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1992). Buddhism Betrayed?: Religion, Politics, and Violence in Sri Lanka. University of Chicago Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-226-78950-0.

- ^ Gunasinghe, Newton (2004). "4: The Open Economy and Its Impact on Ethnic Relations in Sri Lanka". In Winslow, Deborah; Woost, Michael D. (eds.). Economy, Culture, and Civil War in Sri Lanka. Indiana University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-253-34420-4.

- ^ a b c An illustrious son of Sabaragamuwa. Daily News, retrieved on 20 October 2007.

- ^ Life of Sir James Peiris, W. T. Keble and Devar Surya Sena, p.59 (University of California)

- ^ The History of Newspapers in Ceylon (rootsweb) Retrieved 23 December 2014

Further reading

[edit]- Arsecularatne, SN, Sinhalese immigrants in Malaysia & Singapore, 1860-1990: History through recollections, KVG de Silva & Sons, Colombo, 1991

- Brohier, RL, The Golden Age of Military Adventure in Ceylon: an account of the Uva Rebellion 1817-1818. Colombo: 1933

- Crusz, Noel, The Cocos Islands Mutiny, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 2001

- Muthiah, Wesley and Wanasinghe, Sydney, Britain, World War 2 and the Sama Samajists, Young Socialist Publication, Colombo, 1996

- Colvin R. de Silva, Hartal! accessed 4 November 2005.

- Did Japan contribute to Sri Lanka and India to gain independence?

- Sri Lanka won freedom from the British in 1948 largely because of the blood sacrifices of the Japanese soldiers in World War Two, Time to re – write our history books

- Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour ignited the liberation of Asia from Western domination

- Sri Lanka’s Independence – a beneficiary of Japan’s entry to the Second World War which sealed the fate of European Colonialism in Asia

- Four Lankans die in secret 'independence' war

- Sri Lanka and the Yellow Races

- Japan's role in Sri Lanka gaining Independence

- Sri Lanka’s independence: falsehoods and hard facts

- Sri Lanka’s Role In Japanese Peace Treaty 1952: In Retrospect

- Perera, Janaka. "Four Lankans Die in Secret 'Independence' War." WWW Virtual Library: Four Lankans Die in Secret 'Independence' War, www.lankalibrary.com/geo/japan3.htm.