The Imitation Game

| The Imitation Game | |

|---|---|

| File:The Imitation Game poster.jpg Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Morten Tyldum |

| Written by | Graham Moore |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Óscar Faura |

| Edited by | William Goldenberg |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

| Distributed by | StudioCanal (United Kingdom) The Weinstein Company (United States) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 114 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $14 million[2] |

| Box office | $119.6 million[3] |

The Imitation Game is a 2014 historical thriller film about British mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst and pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing who was a key figure in cracking Nazi Germany's naval Enigma code which helped the Allies win the Second World War, only to later be criminally prosecuted for his homosexuality. The film stars Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing, and is directed by Morten Tyldum, with a screenplay by Graham Moore based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges.

The film's screenplay topped the annual Black List for best unproduced Hollywood scripts in 2011. After a bidding process against five other studios, The Weinstein Company acquired the film for $7 million in February 2014, the highest amount ever paid for US distribution rights at the European Film Market. It had its world premiere at the 41st Telluride Film Festival in August 2014. It also featured at the 39th Toronto International Film Festival in September where it won "People's Choice Award for Best Film", the highest award of the festival. It had its European premiere as the opening film of the 58th BFI London Film Festival in October and was released theatrically in the United Kingdom on 14 November, and in the United States on 28 November.

In terms of historical accuracy, while the broad outline of Turing's life as depicted in the film is true, a number of historians have noted that elements within it represent distortions of what actually happened, especially in terms of Turing's work at Bletchley Park during the war and his relationship with friend and fellow code breaker Joan Clarke.

The Imitation Game was both a critical and commercial success. The film was included in both the National Board of Review's and American Film Institute's "Top 10 Films of 2014". At the 87th Academy Awards, it has been nominated in eight categories including Best Picture, Best Director for Tyldum, Best Actor for Cumberbatch and Best Supporting Actress for Keira Knightley. It also garnered five nominations in the 72nd Golden Globe Awards and was nominated in three categories at the 21st Screen Actors Guild Awards including Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture. In addition, it received nine British Academy of Film and Television Arts nominations including Best Film and Outstanding British Film. Its cast and crew were honoured by LGBT civil rights advocacy and political lobbying organisation Human Rights Campaign for bringing Turing's legacy to a wider audience. As of January 2015, the film has grossed a total of $119.6 million worldwide against a $14 million production budget making it the top-grossing independent film release of 2014.

Synopsis

The film shows Alan Turing and his team of code-breakers in Hut 8 racing against time as they attempt to break Nazi Germany's Enigma code at Britain's top-secret Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park during the Second World War. The group of scholars, mathematicians, linguists, chess champions and intelligence officers have a powerful ally in Prime Minister Winston Churchill who authorises the provision of any resource they require.

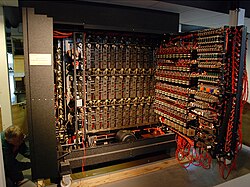

The film spans the key periods of Turing's life: his unhappy teenage years at boarding school; the triumph of his secret wartime work on the revolutionary electro-mechanical bombe, which was capable of breaking 3,000 Enigma-generated naval codes a day; and the tragedy of his post-war decline following his conviction for gross indecency, a criminal offence stemming from his admission of maintaining a homosexual relationship.[4][5][6][7][8]

Cast

- Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing

- Keira Knightley as Joan Clarke[9]

- Matthew Goode as Hugh Alexander[10]

- Mark Strong as Maj. Gen. Stewart Menzies[11]

- Charles Dance as Cdr. Alastair Denniston

- Allen Leech as John Cairncross[12]

- Matthew Beard as Peter Hilton[13]

- Rory Kinnear as Detective Nock[14]

- Alex Lawther as Young Turing

- Jack Bannon as Christopher Morcom

- Victoria Wicks as Dorothy Clarke

- David Charkham as William Kemp Lowther Clarke

- Tuppence Middleton as Helen

- James Northcote as Jack Good

- Steven Waddington as Supt Smith

Production

Before Cumberbatch joined the project, Warner Bros. bought the screenplay for a reported seven-figure sum because of Leonardo DiCaprio's interest in playing Turing.[15][16][17][18][19] In the end, DiCaprio did not come on board and the rights of the script reverted to the screenwriter. Black Bear Pictures subsequently committed to finance the film for $14 million.[20][21][22] Various directors were attached during development including Ron Howard and David Yates.[23] In December 2012, it was announced that Headhunters director Morten Tyldum would helm the project, making the film his English-language directorial debut.[5][24]

Principal photography began on 15 September 2013 in England. Filming locations included Turing's former school, Sherborne and Bletchley Park where Turing and his colleagues worked during the war. Other locations included towns in England; Nettlebed (Joyce Grove at Oxfordshire), and Chesham (Buckinghamshire). Scenes were also filmed at Bicester Airfield and outside the Law Society Building in Chancery Lane. Principal photography finished on 11 November 2013.[25]

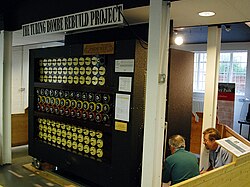

The bombe seen in the film is based on a replica of Turing's original machine, which is housed in the museum at Bletchley Park. Production designer Maria Djurkovic admitted, however, that her team made the machine more cinematic by making it larger and having more of its inside mechanisms visible.[26]

The Weinstein Company acquired the film for $7 million in February 2014, the highest amount ever paid for US distribution rights at the European Film Market.[27] The film is also a recipient of Tribeca Film Festival's Sloan Filmmaker Fund, which grants filmmakers funding and guidance with regards to innovative films that are concerned with science, mathematics and technology.[28]

Title

The film's title refers to Turing's proposed test of the same name, which he discussed in his 1950 paper on artificial intelligence entitled "Computing Machinery and Intelligence".[29] The paper opens: "I propose to consider the question, 'Can machines think?' This should begin with definitions of the meaning of the terms 'machine' and 'think'."

Music

In June 2014, it was announced that Alexandre Desplat would provide the original score of the film.[30] Desplat composed and orchestrated the score in under three weeks.[31] The soundtrack was released by Sony Classical on 24 November 2014. It was recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra at Abbey Road Studios in London.[32]

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Imitation Game" | 2:37 |

| 2. | "Enigma" | 2:50 |

| 3. | "Alan" | 2:57 |

| 4. | "U-boats" | 2:12 |

| 5. | "Carrots and Peas" | 2:19 |

| 6. | "Mission" | 1:36 |

| 7. | "Crosswords" | 2:52 |

| 8. | "Night Research" | 1:39 |

| 9. | "Joan" | 1:45 |

| 10. | "Alone with Numbers" | 2:58 |

| 11. | "The Machine Christopher" | 1:57 |

| 12. | "Running" | 3:01 |

| 13. | "The Headmaster" | 2:27 |

| 14. | "Decrypting" | 2:01 |

| 15. | "A Different Equation" | 2:54 |

| 16. | "Becoming a Spy" | 4:08 |

| 17. | "The Apple" | 2:20 |

| 18. | "Farewell to Christopher" | 2:41 |

| 19. | "End of War" | 2:07 |

| 20. | "Because of You" | 1:36 |

| 21. | "Alan Turing's Legacy" | 1:56 |

| Total length: | 0:51:08 | |

Marketing

Following the Royal Pardon granted by the United Kingdom government to Turing on 24 December 2013, the filmmakers released the first official promotional photograph of Cumberbatch in character beside Turing's bombe on the same day.[34][35] In the week of the anniversary of Turing's death in June 2014, Entertainment Weekly released two new stills which marked the first look at the characters played by Keira Knightley, Matthew Goode, Matthew Beard and Allen Leech.[36] On what would have been Turing's 102nd birthday on 23 June, Empire released two photographs featuring Mark Strong and Charles Dance in character. Promotional stills were taken by photographer Jack English, who also photographed Cumberbatch for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.[37]

Princeton University Press and Vintage Books both released film tie-in editions of Andrew Hodges's biography Alan Turing: The Enigma in September 2014.[38] The first UK and US trailers were released on 22 July 2014.[39] The international teaser poster was released on 18 September 2014 with the tagline, "The true enigma was the man who cracked the code".[40]

On 8 November 2014, The Weinstein Company co-hosted a private screening of the film with Digital Sky Technologies billionaire Yuri Milner and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Attendees of the screening at Los Altos Hills, California included Silicon Valley's top executives including Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, Linkedin’s Reid Hoffman, Google co-founder Sergey Brin, Airbnb’s Nathan Blecharczyk and Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes. Director Tyldum, screenwriter Moore and actress Knightley were also in attendance.[41] In addition, Cumberbatch and Zuckerberg presented the Math Prizes at the Breakthrough Awards on 10 November 2014 in honour of Turing.[42]

The bombe re-created by the filmmakers has been on display in a special The Imitation Game exhibition at Bletchley Park since 10 November 2014. The year-long exhibit features clothes worn by the actors and props used in the film.[43] The official film website at theimitationgamemovie.com allows visitors to unlock exclusive content by solving crossword puzzles conceived by Turing.[45] Google, which sponsored the New York Premiere of the film, launched a competition called "The Code-Cracking Challenge" on 23 November 2014. It is a skill contest where entrants must crack a code provided by Google. The prize/s will be awarded to entrant/s who crack the code and submit their entry the fastest.[46]

On 27 November 2014, ahead of the film's US release, The New York Times reprinted the original 1942 crossword puzzle from The Daily Telegraph used in recruiting codebreakers at Bletchley Park during the Second World War. Entrants who solve the puzzle can mail in their results for a chance to win a trip for two to London and a tour of Bletchley Park.[47]

TWC launched a print and online campaign on 2 January 2015 featuring testimonials from leaders in the fields of technology, military, academia and LGBTQ groups (all influenced by Turing’s life and accomplishments) to promote the film and Turing's legacy. Yahoo! CEO Marissa Mayer, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt, Twitter CEO Dick Costolo, PayPal co-founder Max Levchin, YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki, and Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales all gave tribute quotes. There were also testimonials from LGBT leaders including HRC president Chad Griffin and GLAAD CEO Sarah Kate Ellis and from military leaders including the 22nd United States Defense Secretary Robert Gates.[44][48][49][50]

Theatrical release

The film had its world premiere at the 41st Telluride Film Festival in August 2014, and played at the 39th Toronto International Film Festival in September.[51] It had its European premiere as the opening film of the 58th BFI London Film Festival on October 2014.[52][53] It had a limited theatrical release on 28 November 2014 in the United States, two weeks after its premiere in the United Kingdom on 14 November.[16] The US distributor TWC stated that the film would initially debut in four cinemas in Los Angeles and New York, expanding to six new markets on 12 December before being released nationwide on Christmas day.[54]

Reception

Box office

The film opened number two at the UK box office just behind the big-budget film Interstellar, earning $4.3 million from 459 screens. Its opening box office figure is the third highest opening weekend haul for a UK film in 2014. It achieved a very high 90% “definite recommend” from its core audience, according to exit poll figures. Its opening was 107% higher than that of Argo, 81% higher than Philomena and 26% higher than The Iron Lady following its debut.[55][56]

Debuting in four cinemas in Los Angeles and New York on 28 November, the film grossed $479,352 in its opening weekend with a $119,352 per-screen-average, the second highest per-screen-average of 2014 and the 7th highest of all time for a live-action film. Adjusted for inflation, it outperformed The Weinstein Company's own Oscar-winning films The King's Speech ($88,863 in 2010) and The Artist ($51,220 in 2011), which were also released on Thanksgiving weekend. The film expanded into additional markets on 12 December and was released nationwide on Christmas day.[57][58][59]

The Imitation Game is the top-grossing independent film release of 2014.[60]

Critical response

The film has been met with critical acclaim, with critics particularly lauding Cumberbatch's lead performance as Turing.[61] Rotten Tomatoes sampled 216 critics and judged 90% of the reviews positive with an average rating of 7.7/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "With an outstanding starring performance from Benedict Cumberbatch illuminating its fact-based story, The Imitation Game serves as an eminently well-made entry in the 'prestige biopic' genre."[62] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 72 out of 100, based on 47 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[63] The film received a grade of "A+" from market-research firm CinemaScore and was included in both the National Board of Review's and American Film Institute's "Top 10 Films of 2014".[64][65][66]

The New York Observer's Rex Reed declared that "one of the most important stories of the last century is one of the greatest movies of 2014" while Kaleem Aftab of The Independent gave the film a five-star review hailing it the "Best British Film of the Year".[67][68][69] Lou Lumenick of the New York Post described it as a "thoroughly engrossing Oscar-caliber movie" with critic James Rocchi adding that the film is "strong, stirring, triumphant and tragic".[70] Empire described it as a "superb thriller" and Glamour declared it "an instant classic".[71][72] Peter Debruge of Variety added that the film is "beautifully written, elegantly mounted and poignantly performed".[73] Critic Scott Foundas stated that the "movie is undeniably strong in its sense of a bright light burned out too soon, and the often undignified fate of those who dare to chafe at society's established norms".[74] Critic Leonard Maltin asserted that the film has "an ideal ensemble cast with every role filled to perfection". In addition, praise was given to Knightley's supporting performance as Clarke, Goldenberg's editing, Desplat's score, Faura's cinematography and Djurkovic's production design.[75] The film was enthusiastically received at the Telluride Film Festival and won the "People's Choice Award for Best Film" at TIFF, the highest prize of the festival.

TIME ranked Cumberbatch's portrayal number one in its Top 10 film performances of 2014, with the magazine's chief film critic Richard Corliss calling Cumberbatch's characterisation "the actor’s oddest, fullest, most Cumberbatchian character yet... he doesn’t play Turing so much as inhabit him, bravely and sympathetically but without mediation".[76][77] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times declared Turing "the role of Cumberbatch's career", while A.O. Scott of The New York Times stated that it is "one of the year’s finest pieces of screen acting".[78][79] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone asserted that the actor "gives an explosive, emotionally complex" portrayal. Critic Clayton Davis stated that it's a "performance for the ages ... proving he's one of the best actors working today".[80][81] Foundas of Variety wrote that Cumberbatch's acting is "masterful ... a marvel to watch", Manohla Dargis of The New York Times described it as "delicately nuanced, prickly and tragic" and Owen Gleiberman of the BBC proclaimed it an "emotionally tailored perfection".[82][83] It's "a storming performance from Cumberbatch: you'll be deciphering his work long after the credits roll" declared Dave Calhoun of Time Out.[84] In addition, Claudia Puig of USA Today concluded in her review, "It's Cumberbatch's nuanced, haunted performance that leaves the most powerful impression".[85] The Hollywood Reporter's Todd McCarthy reported that the undeniable highlight of the film was Cumberbatch, "whose charisma, tellingly modulated and naturalistic array of eccentricities, talent at indicating a mind never at rest and knack for simultaneously portraying physical oddness and attractiveness combine to create an entirely credible portrait of genius at work".[86][87] Critic Roger Friedman wrote at the end of his review, "Cumberbatch may be the closest thing we have to a real descendant of Sir Laurence Olivier".[88]

While praising the performances of Cumberbatch and Knightley, Catherine Shoard of The Guardian stated that the film is "too formulaic, too efficient at simply whisking you through and making sure you've clocked the diversity message".[89] Tim Robey of The Telegraph described it as "a film about a human calculator which feels ... a little too calculated".[90] Some critics also raised concerns about the lack of sex scenes in the film to highlight Turing's homosexuality.[91] British historian Alex von Tunzelmann, writing for The Guardian in November 2014, pointed out many historical inaccuracies in the film, saying in conclusion: "Historically, The Imitation Game is as much of a garbled mess as a heap of unbroken code".[92] Journalist Christian Caryl also found numerous historical inaccuracies, describing the film as constituting "a bizarre departure from the historical record" that changed Turing's rich life to be "multiplex-friendly".[93] L.V. Anderson of Slate magazine compared the film's account of Turing's life and work to the biography it was based on, writing, "I discovered that The Imitation Game takes major liberties with its source material, injecting conflict where none existed, inventing entirely fictional characters, rearranging the chronology of events, and misrepresenting the very nature of Turing's work at Bletchley Park".[94] Andrew Grant of Science News wrote, "... like so many other Hollywood biopics, it takes some major artistic license – which is disappointing, because Turing's actual story is so compelling."[95]

The Turing family

Despite earlier reservations, Turing's niece Inagh Payne told Allan Beswick of BBC Radio Manchester that "the film really did honour my uncle" after she watched the film at the London Film Festival in October 2014. In the same interview, Turing's nephew Dermont Turing stated that Cumberbatch is "perfect casting. I couldn't think of anyone better". James Turing, a great-nephew of the codebreaker, said Cumberbatch "knows things that I never knew before. The amount of knowledge he has about Alan is amazing".[96]

Social action

"Alan Turing was not only prosecuted, but quite arguably persuaded to end his own life early, by a society who called him a criminal for simply seeking out the love he deserved, as all human beings do. 60 years later, that same government claimed to ‘forgive’ him by pardoning him. I find this deplorable, because Turing’s actions did not warrant forgiveness — theirs did — and the 49,000 other prosecuted men deserve the same."

—Cumberbatch in support for pardoning gay men convicted of United Kingdom's laws on homosexual acts[97]

On 23 January 2015, LGBTQ activist Stephen Fry together with Harvey Weinstein and Cumberbatch launched a campaign to pardon the 49,000 gay men convicted under the same law that led to Turing's chemical castration. Fry stated: "Should Alan Turing have been pardoned just because he was a genius when somewhere between 50 to 70 thousand other men were imprisoned, chemically castrated, had their lives ruined or indeed committed suicide because of the laws under which Turing suffered? There is a general feeling that perhaps if he should be pardoned, then perhaps so should all of those men, whose names were ruined in their lifetime, but who still have families. It was a nasty, malicious and horrific law and one that allowed so much blackmail and so much misery and so much distress. Turing stands as a figure symbolic to his own age in the way that Oscar Wilde was, who suffered under a more but similar one." Human Rights Campaign's Chad Griffin also offered his endorsement and said: "Over 49,000 other gay men and women were persecuted in England under the same law. Turing was pardoned by Queen Elizabeth II in 2013. The others were not. Honor this movie. Honor this man. And honor the movement to bring justice to the other 49,000." Aiding the cause are campaigner Peter Tatchell, Attitude magazine and other high-profile figures in the gay community.[98][99]

Controversy

During production, there was criticism regarding the film's purported downplaying of Alan Turing's homosexuality,[100] particularly condemning the portrayal of his relationship with close friend and one-time fiancée Joan Clarke. Hodges, author of the book the film was based on, described the script as having "built up the relationship with Joan much more than it actually was".[21][101][102][103] Turing's surviving niece Payne thought that Knightley was inappropriately cast as Clarke, whom she described as "rather plain".[104]

Speaking to Empire, director Tyldum expressed his decision on taking on the project: "It is such a complex story. It was the gay rights element, but also how his (Turing's) ideas were kept secret and how incredibly important his work was during the war, that he was never given credit for it".[37] In an interview for GQ UK, Goode, who plays a fellow cryptographer of Turing in the film, stated that the script focuses on "Turing's life and how as a nation we celebrated him as being a hero by chemically castrating him because he was gay".[105] In addition, the producers of the film officially stated: "There is not – and never has been – a version of our script where Alan Turing is anything other than homosexual, nor have we included fictitious sex scenes".[106]

In a January 2015 interview with The Huffington Post in response to general complaints about the level of historical accuracy in the film, its screenwriter Moore said: "When you use the language of 'fact checking' to talk about a film, I think you're sort of fundamentally misunderstanding how art works. You don't fact check Monet's 'Water Lilies'. That's not what water lilies look like, that's what the sensation of experiencing water lilies feel like. That's the goal of the piece."[107] In the same interview, director Tyldum stated: "A lot of historical films sometimes feel like people reading a Wikipedia page to you onscreen, like just reciting 'and then he did that, and then he did that, and then he did this other thing' – it's like a 'Greatest Hits' compilation. We wanted the movie to be emotional and passionate. Our goal was to give you 'What does Alan Turing feel like?' What does his story feel like? What'd it feel like to be Alan Turing? Can we create the experience of sort of 'Alan Turing-ness' for an audience based on his life?"[107]

Accuracy

Like most films based on historical events, The Imitation Game has received criticism for inaccuracies regarding the events and people it portrays.

Historical events

- Suggesting that the work at Bletchley Park was the effort of a small group of cryptographers who were stymied for the first few years of the war until a sudden breakthrough that allowed them to break Enigma.

- Progress was actually made from the beginning of the war in 1939 and thousands of people were working on the project before the war ended in 1945. Throughout the war there were breakthroughs and setbacks when the design or use of the German Enigma machines was changed and the Bletchley Park code breakers had to adapt.[93]

- Naming the Enigma-breaking machine "Christopher" after Turing's childhood friend.

- In actuality, this electromechanical machine was called 'Victory'. Victory was a British Bombe machine, which drew a spiritual legacy from a design by the Polish Cryptanalyst Marian Rejewski. Rejewski designed a machine in 1938 called bomba kryptologiczna which exploited a particular, but temporary, weakness in German operating procedures. A new machine with a different strategy was designed by Turing (with a key contribution from mathematician Gordon Welchman, unmentioned in the film) in 1940. More than 200 British Bombes were built under the supervision of Harold Keen of the British Tabulating Machine Company.[94][92]

- Showing a scene where the Hut 8 team decides not to use broken codes to stop a German raid on a convoy that the brother of one of the code breakers (Peter Hilton) is serving on, in order to hide the fact they have broken the code.

- In reality, Hilton had no such brother, and decisions about when and whether to use data from Ultra intelligence were made at much higher administrative levels.[94]

- Showing Turing writing a letter to Churchill in order to gain control over Enigma breaking and obtain funding for the decryption machine.

- Turing was actually not alone in making a different request with a number of his colleagues, including Hugh Alexander, writing a letter to Churchill (who had earlier visited there) in an effort to get more administrative resources sent to Bletchley Park, which Churchill immediately did.[94]

- Showing a Dornier Do 17 performing a reconnaissance mission against an Allied convoy.

- In reality, the Do 17 had too short a range to perform a reconnaissance mission in the Atlantic. This role was carried out by long-range aircraft such as the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor.

Turing's personality and personal life

- Exaggerating Turing's social difficulties to the point of depicting him having Asperger syndrome or otherwise being on the autism spectrum.

- While a few writers and researchers have tried to assign such a retrospective diagnosis to Turing,[108] and it is true that he had his share of eccentricities, the Asperger's-like traits portrayed in the film – an intellectual snob with no friends, no sense of how to work cooperatively with others, and no understanding of humour – bear little relationship to the actual adult Turing, who had friends, was viewed as having a sense of humour and had good working relationships with his colleagues.[109][93][110]

- Scenes about Turing's childhood friend, including the manner in which Turing learned of Morcom's illness and death.[94][92]

- Portraying Turing's arrest as happening in 1951 and having a detective suspect him of being a Soviet spy until Turing tells his codebreaking story in an interview with the detective, who then discovers Turing is gay.

- Turing's arrest was in 1952. The detective in the film and the interview as portrayed are fictional. Turing was investigated for his homosexuality after a robbery at his house and was never investigated for espionage.[92]

- Suggesting that the chemical castration that Turing was forced to undergo made him unable to think clearly or do any work.

- Despite physical weakness and changes in Turing's body including gynecomastia, at that time he was doing innovative work on mathematical biology, inspired by the very changes his body was undergoing due to chemical castration.[93][94]

- Clarke visiting Turing in his home while he is serving probation.

- There is no record of Clarke ever visiting Turing's residence during his probation, although Turing did stay in touch with her after the war and informed her of his upcoming trial for indecency.[94]

- Stating outright that Turing committed suicide after a year of hormone treatment.

- In reality, the nature of Turing's death is a matter of considerable debate. The chemical castration period ended fourteen months before his death. The official inquest into his death ruled that he had committed suicide by consuming a cyanide-laced apple. Turing biographer Andrew Hodges believes the death was indeed a suicide, re-enacting the poisoned apple from Snow White, Turing's favourite fairy tale, with some deliberate ambiguity included to permit Turing's mother to interpret it as an accident. However Jack Copeland, an editor of volumes of Turing's work and Director of the Turing Archive for the History of Computing, has suggested that Turing's death may have been accidental, caused by the cyanide fumes produced by an experiment in his spare room, and that the coroner's investigation was poorly conducted.[94][112]

Personalities and actions of other characters

- Depicting Commander Denniston as a rigid officer, bound by military thinking and eager to shut down the decryption machine when it fails to deliver results.

- Denniston's grandchildren stated that the film takes an "unwarranted sideswipe" at their grandfather's memory, showing him to be a "baddy" and a "hectoring character" who hinders the work of Turing. They said their grandfather had a completely different temperament from the one portrayed in the film and was entirely supportive of the work done by cryptographers under his command.[94][113] There is no record of the film's depicted interactions between Turing and Denniston. In addition, Turing was always respected and considered one of the best code breakers at Bletchley Park.[94]

- Showing Turing interacting with Stewart Menzies, head of the British Secret Intelligence Service.

- There are no records showing they interacted at all during Turing's time at Bletchley Park.[94]

- Including an espionage subplot involving Turing working with John Cairncross.

- Turing and Cairncross worked in different areas of Bletchley Park and there is no evidence they ever met.[93][94] Historian Von Tunzelmann was angered by this subplot (which suggests that Turing was for a while blackmailed into not revealing Cairncross as a spy lest his homosexuality be revealed), writing that "Creative licence is one thing, but slandering a great man's reputation – while buying into the nasty 1950s prejudice that gay men automatically constituted a security risk – is quite another."[92]

Accolades

The Imitation Game has been nominated for, and has received, numerous awards, with Cumberbatch's portrayal of Turing particularly praised.[114][115][116][117] The film and its cast and crew were also honoured by Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBT civil rights advocacy group and political lobbying organisation in the United States. "We are proud to honor the stars and filmmakers of The Imitation Game for bringing the captivating yet tragic story of Alan Turing to the big screen", HRC president Chad Griffin said in a statement.[118]

References

- ^ "THE IMITATION GAME (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ "The Weinstein Co. Special: How They Turned 'Imitation Game' Director Into an Oscar Contender". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ "The Imitation Game (2014) - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Powell, Lucy (2014). "The Imitation Game". Optimum Releasing. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ a b Charles, McGrath (30 October 2014). "The Riddle Who Unlocked the Enigma - 'The Imitation Game' Dramatizes the Story of Alan Turing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game". The Weinstein Company. 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (12 December 2011). "The Black List 2011: Screenplay Roster". Deadline. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Copeland, Jack (19 June 2012). "Alan Turing: The codebreaker who saved 'millions of lives'". BBC News. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Kit, Borys (4 June 2013). "Keira Knightley to Star Opposite Benedict Cumberbatch in 'Imitation Game'". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Puchko, Kristy (17 June 2013). "Matthew Goode Joins Benedict Cumberbatch For Alan Turing Biopic". Cinemablend. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (September 2013). "Mark Strong Joins THE IMITATION GAME, Ben Kingsley and Patricia Clarkson Lead LEARNING TO DRIVE". Collider. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Kroll, Justin (27 August 2013). "'Downton Abbey' Actor Allen Leech Joins Cumberbatch in 'Imitation Game'". Variety. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (16 September 2013). "Matthew Goode, Mark Strong and Rory Kinnear Join Cast of 'The Imitation Game'". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (16 September 2013). "Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley begin shoot on The Imitation Game". Screen Daily. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Thompson, Anne. "Imitation Game Release Date Changed to November 28".

- ^ a b STUDIOCANAL UK (13 May 2014). "Delighted to announce Alan Turing #movie THE IMITATION GAME w Benedict Cumberbatch will have it's UK release on Nov 14th 2014 @tigmovie". Twitter. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (1 February 2013). "Benedict Cumberbatch In Talks To Play Alan Turing In 'The Imitation Game'". Deadline. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Lussier, Germain (16 September 2013). "'The Imitation Game' Begins Filming With Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley". Slash Film. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (11 October 2011). "Warner Bros Buys Spec Script About Math Genius Alan Turing For Leonardo DiCaprio". Deadline. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "The Weinstein Co. Special: How They Turned 'Imitation Game' Director Into an Oscar Contender". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ a b Fleming, Mike (16 December 2011). "Warner Bros Sets Black List Top Scribe Graham Moore For 'Devil In The White City'; Leonardo DiCaprio To Play Serial Killer". Deadline. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (August 2012). "Leonardo DiCaprio Exits THE IMITATION GAME; Warner Bros. Backs Out of the Alan Turing Project". Collider. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (14 November 2011). "David Yates Develops 'Dr. Who,' As Warner Bros Tempts Him With 'Imitation Game'". deadline.com. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (4 December 2012). "'Headhunters' Helmer Morten Tyldum To Direct 'The Imitation Game'". Deadline. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Sherlock's on the trail of a new movie blockbuster". The Oxford Times. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Watercutter, Angela. "Building Christopher". Slate.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (7 February 2014). "Harvey Weinstein Pays Record $7 Million For 'Imitation Game' Movie". Deadline. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game". Tribeca Film Institute. 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Hodges, Andrew (2014). "The Turing Test, 1950". Alan Turing Internet Scrapbook. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Alexandre Desplat Takes Over Scoring Duties on 'The Imitation Game'". Film Music Reporter. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Ge, Linda. "TheWrap Screening Series: 'Imitation Game' Filmmakers on Casting Benedict Cumberbatch and Going Indie (Video)". thewrap.com.

- ^ Roberts, Shiela. "Composer Alexandre Desplat Talks THE IMITATION GAME, Coming to the Project Late, Finding Continuity in His Scores, His Love of Conducting, and More". Collider.com.

- ^ Laurent, Olivier. "Go Behind TIME's Benedict Cumberbatch Cover With Photographer Dan Winters". TIME.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (26 December 2013). "Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing in First Look at 'The Imitation Game' (Photo)". TheWrap. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ The Imitation Game (24 December 2013). "In honor of today's Royal Pardon, please find the first still released from the upcoming film, The Imitation Game". Twitter. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (5 June 2014). "Benedict Cumberbatch outwits Nazis in 'The Imitation Game' -- FIRST LOOK". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ a b de Semlyen, Phil (23 June 2014). "New Stills Of Benedict Cumberbatch And Keira Knightley In The Imitation Game". Empire. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Dougherty, Peter (3 June 2014). "June, summer, and Princeton University Press in the movies". blog.press.princeton.edu. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game will open the 58th BFI London Film Festival". British Film Institute. 3 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "New Teaser Poster For The Imitation Game Arrives Online". empireonline.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike. "Zuckerberg, Weinstein Play 'The Imitation Game' With Tech Titans: Oscar Watch". Deadline.

- ^ Stone, Brad. "Mark Zuckerberg Interview: Breakthrough Prizes and Turning Scientists Into Heroes Again". Business Week.

- ^ "THE IMITATION GAME: Bletchley Park opens exhibit after Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley film there". MK Web.

- ^ a b Fleming Jr., Mike. "Who Is Alan Turing? 'Imitation Game' Oscar Ads Focus On A Hero". Deadline.

- ^ The Imitation Game website, theimitationgamemovie.com; accessed 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game with Google". Google.

- ^ Lattanzio, Ryan. "Weinstein Plants Clever 'Imitation Game' FYC Ploy in New York Times". Thompson on Hollywood.

- ^ "Industry leaders recognize the genius of Alan Turing's contributions to the world". Twitter.

- ^ Schmidt, Eric. "Every time you use a phone, or a computer, you use the ideas that Alan Turing invented. A hero". Twitter.

- ^ Costolo, Dick. "Psyched about this combination of subject/actor. Spent a good deal of time @umich on Turing machines, computability". Twitter.

- ^ Bailey, Cameron (2014). "The Imitation Game". TIFF.net. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Zuckerman, Esther (28 August 2014). "Telluride Film Festival lineup includes 'Wild', 'The Imitation Game'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (21 July 2014). "'The Imitation Game' to Open BFI London Film Festival". Variety. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "'Imitation Game' Scores Huge Debut Thanks to Oscar Buzz, Benedict Cumberbatch". Variety. 30 November 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ Gant, Charles. "The Imitation Game cracks UK box office, Interstellar keeps high orbit". The Guardian.

- ^ Jafaar, Ali. "'Imitation Game' No Pretender At UK Box Office". Deadline.

- ^ "'The Imitation Game' For Real: Year's 2nd-Best Debut Per Theater". Deadline.

- ^ "'Imitation Game' Scores Huge Debut Thanks to Oscar Buzz, Benedict Cumberbatch". Variety.

- ^ "Specialty Box Office: 'Imitation Game' Nabs Top Theater Average of Fall Awards Season". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Lang, Brent. ""The Imitation Game" officially became the top-grossing indie release of 2014". Variey.

- ^ "Cumberbatch is remarkable in Imitation Game", firstshowing.net; accessed 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "The Imitation Game Reviews". metacritic.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Imitation Game, Interstellar make AFI best films of the year". The Telegraph.

- ^ "A Most Violent Year named best film by National Board of Review". BBC.

- ^ "Box Office: Thanksgiving Holiday Moviegoing Plummets". Yahoo.

- ^ Reed, Rex. "True and Tragic, 'The Imitation Game' Is an Intimate Look at the Life of Alan Turing". The New York Observer.

- ^ "NEW 'THE IMITATION GAME' TRAILER KEEPS IT QUICK AND CUMBERBATCHIAN". http://www.iamrogue.com/.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "The Imitation Game, film review: Benedict Cumberbatch gives Oscar worthy performance". The Independent. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Benedict Cumberbatch foils Nazis in Oscar-caliber 'Imitation Game'". New York Post. 10 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game - NEW Official UK Trailer". YouTube. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Review: 'The Imitation Game'". Film.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Fall Festivals: Critics Pick Favorites From Venice, Telluride and Toronto - Variety". Variety. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "'The Imitation Game' Review: Benedict Cumberbatch Triumphs in a Classy but Conventional Bio-pic". Variety. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Telluride 2014: Cumberbatch is Remarkable in 'The Imitation Game'". FirstShowing.net. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Top 10 Best Movie Performances". TIME magazine.

- ^ Corliss, Richard. "Review: The Imitation Game: Dancing With Dr. Strange". Time.com.

- ^ Scott, A.O. "Broken Codes, Both Strategic and Social". The New York Times.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth. "'Imitation Game' a crackerjack tale about Enigma buster Alan Turing". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "The Imitation Game cracks code to win People's Choice Award at Toronto 2014". the Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Clayton Davis. "Film Review: The Imitation Game (????)". AwardsCircuit.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Review: The Imitation Game and The Theory of Everything". BBC Culture. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Toronto Film Festival coverage, nytimes.com, 13 September 2014; accessed 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game". Time Out London. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (26 November 2014). "Review: Cumberbatch cracks Oscar's code in 'Imitation'". USA Today.

- ^ "'The Imitation Game': Telluride Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Telluride: Benedict Cumberbatch Leads Weinstein's 'Imitation Game' Into Oscar Fray". The Hollywood Reporter. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Toronto sings Cumberbatch's praises as WWII code-breaker". 10 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game review: Knightley and Cumberbatch impress, but historical spoilers lower the tension". the Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Tim Robey (9 September 2014). "The Imitation Game, review: 'clever, calculated'". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "The Imitation Game is strangely shy about Alan Turing's sexuality". the Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Alex von Tunzelmann (20 November 2014). "The Imitation Game: inventing a new slander to insult Alan Turing". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e Christian Caryl (19 December 2014). "A Poor Imitation of Alan Turing". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Anderson, L.V. (3 December 2014). "How Accurate Is The Imitation Game? We've Separated Fact From Fiction". Slate.

- ^ Grant, Andrew (30 December 2014). "'The Imitation Game' entertains at the expense of accuracy". Science News.

- ^ Beswick, Allan. "Turing's family on The Imitation Game". Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott. "Benedict Cumberbatch, Stephen Fry Call for Pardons for Gays Persecuted Alongside 'Imitation Game' Subject". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Foster, Alistair. "Stephen Fry's campaign to pardon all gay men ruined by 'malicious' law". Evening Standard.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott. "Benedict Cumberbatch, Stephen Fry Call for Pardons for Gays Persecuted Alongside 'Imitation Game' Subject". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Lucas, Harriet (31 July 2013). "Comment: Hollywood should stay true to the real story of Alan Turing". Pink News. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Hanks, E.A. (27 September 2013). "How Benedict Cumberbatch And Alan Turing Helped A Writer Find Success In Hollywood". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ Mack, Andrew (13 December 2012). "Tyldum Leaves TORDENSKIOLD Biopic Afloat. Instead, Will Decrypt THE IMITATION GAME". Twitch. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Day, Aaron (24 June 2013). "Alan Turing's biographer criticises upcoming biopic for downplaying gay identity". Pink News. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Lazarus, Susanna (19 November 2013). "Imitation Game filmmakers accused of romanticising the relationship between Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley's characters by Alan Turing's niece, Inagh Payne". Radio Times. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Carvell, Nick (25 June 2013). "Matthew Goode announced as new face of Hogan Shoes". GQ Magazine. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Scott (19 August 2013). "Producers of Alan Turing film reject criticism of project". Pink News. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ a b Katz, Emily Tess (8 January 2015). "'Imitation Game' Writer Slams 'Fact-Checking' Films As Misunderstanding Of Art". Huffington Post.

- ^ O'Connell, H.; Fitzgerald, M. (2003). "Did Alan Turing have Asperger's syndrome?". Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 20 (1): 28–31.

- ^ Young, Toby (10 January 2015). "The misguided bid to turn Alan Turing into an Asperger's martyr". The Spectator. UK.

- ^ Alan Turing: The Enigma, Burnett Books Ltd, 1983. ISBN 0-09-911641-3, pp. 272–3.

- ^ "Poor Imitation of Alan Turing". New York Review of Books.

- ^ Pease, Roland (26 June 2012). "Alan Turing: Inquest's suicide verdict 'not supportable'". BBC News.

- ^ "Bletchley Park commander not the 'baddy' he is in The Imitation Game, family say". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Golden Globes: 'Birdman,' 'Fargo' Top Nominations". Variety.

- ^ "'Birdman,' 'Modern Family' Lead SAG Awards Nominations with Four". Variety.

- ^ "Benedict Cumberbatch cracks the code to make Bletchley Park a hit". Daily Express. 9 November 2014.

- ^ "Top 10 Best Movie Performances (#1 Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing in The Imitation Game)". Time.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott. "'The Imitation Game' to Be Honored by Human Rights Campaign". The Hollywood Reporter.

External links

- Official website

- The Imitation Game at IMDb

- The Imitation Game at Box Office Mojo

- The Imitation Game at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Imitation Game at Metacritic

- The Imitation Game at History vs. Hollywood

- 2014 films

- Alan Turing

- Bletchley Park

- 2010s LGBT-related films

- 2010s thriller films

- 2010s war films

- British films

- British thriller films

- British LGBT-related films

- British war films

- American films

- American LGBT-related films

- American war films

- English-language films

- Films based on biographies

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Buckinghamshire

- Films shot in Dorset

- Films shot in Oxfordshire

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in England

- Independent films

- FilmNation Entertainment films

- StudioCanal films

- The Weinstein Company films

- World War II films