Ultimate fate of the universe

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

The ultimate fate of the universe is a topic in physical cosmology, whose theoretical restrictions allow possible scenarios for the evolution and ultimate fate of the universe to be described and evaluated. Based on available observational evidence, deciding the fate and evolution of the universe have now become valid cosmological questions, being beyond the mostly untestable constraints of mythological or theological beliefs. Many possible dark futures have been predicted by rival scientific hypotheses, including that the universe might have existed for a finite and infinite duration, or towards explaining the manner and circumstances of its beginning.

Observations made by Edwin Hubble during the 1920s–1950s found that galaxies appeared to be moving away from each other, leading to the currently accepted Big Bang theory. This suggests that the universe began–very small and very dense–about 13.8 billion years ago, and it has expanded and (on average) become less dense ever since.[1] Confirmation of the Big Bang mostly depends on knowing the rate of expansion, average density of matter, and the physical properties of the mass–energy in the universe.

There is a strong consensus[who?] among cosmologists that the universe is "flat" (see Shape of the universe) and will continue to expand forever.[2][3]

Factors that need to be considered in determining the universe's origin and ultimate fate include: the average motions of galaxies, the shape and structure of the universe, and the amount of dark matter and dark energy that the universe contains.

Emerging scientific basis

Theory

The theoretical scientific exploration of the ultimate fate of the universe became possible with Albert Einstein's 1915 theory of general relativity. General relativity can be employed to describe the universe on the largest possible scale. There are many possible solutions to the equations of general relativity, and each solution implies a possible ultimate fate of the universe.

Alexander Friedmann proposed several solutions in 1922, as did Georges Lemaître in 1927.[4] In some of these solutions, the universe has been expanding from an initial singularity which was, essentially, the Big Bang.

Observation

In 1931, Edwin Hubble published his conclusion, based on his observations of Cepheid variable stars in distant galaxies, that the universe was expanding. From then on, the beginning of the universe and its possible end have been the subjects of serious scientific investigation.

Big Bang and Steady State theories

In 1927, Georges Lemaître set out a theory that has since come to be called the Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe.[4] In 1948, Fred Hoyle set out his opposing Steady State theory in which the universe continually expanded but remained statistically unchanged as new matter is constantly created. These two theories were active contenders until the 1965 discovery, by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, of the cosmic microwave background radiation, a fact that is a straightforward prediction of the Big Bang theory, and one that the original Steady State theory could not account for. As a result, The Big Bang theory quickly became the most widely held view of the origin of the universe.

Cosmological constant

When Einstein formulated general relativity, he and his contemporaries believed in a static universe. When Einstein found that his equations could easily be solved in such a way as to allow the universe to be expanding now, and to contract in the far future, he added to those equations what he called a cosmological constant, essentially a constant energy density unaffected by any expansion or contraction, whose role was to offset the effect of gravity on the universe as a whole in such a way that the universe would remain static. After Hubble announced his conclusion that the universe was expanding, Einstein wrote that his cosmological constant was "the greatest blunder of my life."[5]

Density parameter

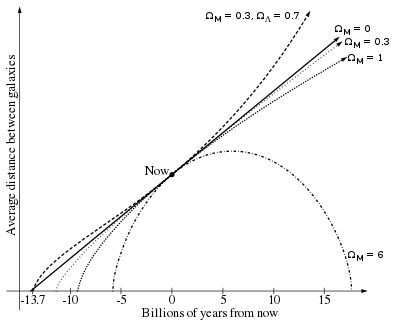

An important parameter in fate of the universe theory is the density parameter, omega (), defined as the average matter density of the universe divided by a critical value of that density. This selects one of three possible geometries depending on whether is equal to, less than, or greater than . These are called, respectively, the flat, open and closed universes. These three adjectives refer to the overall geometry of the universe, and not to the local curving of spacetime caused by smaller clumps of mass (for example, galaxies and stars). If the primary content of the universe is inert matter, as in the dust models popular for much of the 20th century, there is a particular fate corresponding to each geometry. Hence cosmologists aimed to determine the fate of the universe by measuring , or equivalently the rate at which the expansion was decelerating.

Repulsive force

Starting in 1998, observations of supernovas in distant galaxies have been interpreted as consistent[6] with a universe whose expansion is accelerating. Subsequent cosmological theorizing has been designed so as to allow for this possible acceleration, nearly always by invoking dark energy, which in its simplest form is just a positive cosmological constant. In general, dark energy is a catch-all term for any hypothesised field with negative pressure, usually with a density that changes as the universe expands.

Role of the shape of the universe

The current scientific consensus of most cosmologists is that the ultimate fate of the universe depends on its overall shape, how much dark energy it contains, and on the equation of state which determines how the dark energy density responds to the expansion of the universe.[3] Recent observations conclude, from 7.5 billion years after the Big Bang, that the expansion rate of the universe has likely been increasing, commensurate with the Open Universe theory.[7] However, other recent measurements by Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe suggest that the universe is either flat or very close to flat.[2]

Closed universe

If , then the geometry of space is closed like the surface of a sphere. The sum of the angles of a triangle exceeds 180 degrees and there are no parallel lines; all lines eventually meet. The geometry of the universe is, at least on a very large scale, elliptic.

In a closed universe, gravity eventually stops the expansion of the universe, after which it starts to contract until all matter in the universe collapses to a point, a final singularity termed the "Big Crunch", the opposite of the Big Bang. Some new modern theories assume the universe may have a significant amount of dark energy, whose repulsive force may be sufficient to cause the expansion of the universe to continue forever—even if .[8]

Open universe

If , the geometry of space is open, i.e., negatively curved like the surface of a saddle. The angles of a triangle sum to less than 180 degrees, and lines that do not meet are never equidistant; they have a point of least distance and otherwise grow apart. The geometry of such a universe is hyperbolic.

Even without dark energy, a negatively curved universe expands forever, with gravity negligibly slowing the rate of expansion.[citation needed] With dark energy, the expansion not only continues but accelerates.[citation needed] The ultimate fate of an open universe is either universal heat death, the "Big Freeze", or the "Big Rip",[citation needed] where the acceleration caused by dark energy eventually becomes so strong that it completely overwhelms the effects of the gravitational, electromagnetic and strong binding forces.

Conversely, a negative cosmological constant, which would correspond to a negative energy density and positive pressure, would cause even an open universe to re-collapse to a big crunch. This option has been ruled out by observations.[citation needed]

Flat universe

If the average density of the universe exactly equals the critical density so that , then the geometry of the universe is flat: as in Euclidean geometry, the sum of the angles of a triangle is 180 degrees and parallel lines continuously maintain the same distance. Measurements from Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe have confirmed the universe is flat with only a 0.4% margin of error.[2]

In absence of dark energy, a flat universe expands forever but at a continually decelerating rate, with expansion asymptotically approaching zero.[citation needed] With dark energy, the expansion rate of the universe initially slows down, due to the effect of gravity, but eventually increases.[citation needed] The ultimate fate of the universe is the same as an open universe.

Theories about the end of the universe

The fate of the universe is determined by its density. The preponderance of evidence to date, based on measurements of the rate of expansion and the mass density, favors a universe that will continue to expand indefinitely, resulting in the "Big Freeze" scenario below.[9] However, observations are not conclusive, and alternative models are still possible.[10]

Big Freeze or heat death

The Big Freeze is a scenario under which continued expansion results in a universe that asymptotically approaches absolute zero temperature.[11] This scenario, in combination with the Big Rip scenario, is currently gaining ground as the most important hypothesis.[12] It could, in the absence of dark energy, occur only under a flat or hyperbolic geometry. With a positive cosmological constant, it could also occur in a closed universe. In this scenario, stars are expected to form normally for 1012 to 1014 (1–100 trillion) years, but eventually the supply of gas needed for star formation will be exhausted. As existing stars run out of fuel and cease to shine, the universe will slowly and inexorably grow darker. Eventually black holes will dominate the universe, which themselves will disappear over time as they emit Hawking radiation.[13] Over infinite time, there would be a spontaneous entropy decrease by the Poincaré recurrence theorem, thermal fluctuations,[14][15] and the fluctuation theorem.[16][17]

A related scenario is heat death, which states that the universe goes to a state of maximum entropy in which everything is evenly distributed and there are no gradients—which are needed to sustain information processing, one form of which is life. The heat death scenario is compatible with any of the three spatial models, but requires that the universe reach an eventual temperature minimum.[18]

Big Rip

In the special case of phantom dark energy, which has even more negative pressure than a simple cosmological constant, the density of dark energy increases with time, causing the rate of acceleration to increase, leading to a steady increase in the Hubble constant. As a result, all material objects in the universe, starting with galaxies and eventually (in a finite time) all forms, no matter how small, will disintegrate into unbound elementary particles and radiation, ripped apart by the phantom energy force and shooting apart from each other. The end state of the universe is a singularity, as the dark energy density and expansion rate becomes infinite.

Big Crunch

The Big Crunch hypothesis is a symmetric view of the ultimate fate of the universe. Just as the Big Bang started as a cosmological expansion, this theory assumes that the average density of the universe will be enough to stop its expansion and begin contracting. The end result is unknown; a simple estimation would have all the matter and space-time in the universe collapse into a dimensionless singularity back into how the universe started with the Big Bang, but at these scales unknown quantum effects need to be considered (see Quantum gravity). Recent evidence suggests that this scenario is not likely but it has not been ruled out as measurements are only available over a short period of time and could reverse in the future.[12]

This scenario allows the Big Bang to occur immediately after the Big Crunch of a preceding universe. If this happens repeatedly, it creates a cyclic model, which is also known as an oscillatory universe. The universe could then consist of an infinite sequence of finite universes, with each finite universe ending with a Big Crunch that is also the Big Bang of the next universe. Theoretically, the cyclic universe could not be reconciled with the second law of thermodynamics: entropy would build up from oscillation to oscillation and cause heat death. Current evidence also indicates the universe is not closed. This has caused cosmologists to abandon the oscillating universe model. A somewhat similar idea is embraced by the cyclic model, but this idea evades heat death because of an expansion of the branes that dilutes entropy accumulated in the previous cycle.[citation needed]

Big Bounce

The Big Bounce is a theorized scientific model related to the beginning of the known universe. It derives from the oscillatory universe or cyclic repetition interpretation of the Big Bang where the first cosmological event was the result of the collapse of a previous universe.

According to one version of the Big Bang theory of cosmology, in the beginning the universe was infinitely dense. Such a description seems to be at odds with everything else in physics, and especially quantum mechanics and its uncertainty principle.[citation needed] It is not surprising, therefore, that quantum mechanics has given rise to an alternative version of the Big Bang theory. Also, if the universe is closed, this theory would predict that once this universe collapses it will spawn another universe in an event similar to the Big Bang after a universal singularity is reached or a repulsive quantum force causes re-expansion.

In simple terms, this theory states that the universe will continuously repeat the cycle of a Big Bang, followed up with a Big Crunch.

False vacuum

In order to best understand the false vacuum collapse theory, one must first understand the Higgs field which permeates the universe. Much like an electromagnetic field, it varies in strength based upon its potential. A true vacuum exists so long as the universe exists in its lowest energy state, in which case the false vacuum theory is irrelevant. However, if the vacuum is not in its lowest energy state (a false vacuum), it could tunnel into a lower energy state.[19] This is called vacuum decay. This has the potential to fundamentally alter our universe; in more audacious scenarios even the various physical constants could have different values, severely affecting the foundations of matter, energy, and spacetime. It is also possible that all structures will be destroyed instantaneously, without any forewarning.[20] Studies of a particle similar to the Higgs boson support the theory of a false vacuum collapse billions of years from now.[21]

Cosmic uncertainty

Each possibility described so far is based on a very simple form for the dark energy equation of state. But as the name is meant to imply, very little is currently known about the physics of dark energy. If the theory of inflation is true, the universe went through an episode dominated by a different form of dark energy in the first moments of the Big Bang; but inflation ended, indicating an equation of state far more complex than those assumed so far for present-day dark energy. It is possible that the dark energy equation of state could change again resulting in an event that would have consequences which are extremely difficult to predict or parametrize. As the nature of dark energy and dark matter remain enigmatic, even hypothetical, the possibilities surrounding their coming role in the universe are currently unknown.

Observational constraints on theories

Choosing among these rival scenarios is done by 'weighing' the universe, for example, measuring the relative contributions of matter, radiation, dark matter, and dark energy to the critical density. More concretely, competing scenarios are evaluated against data on galaxy clustering and distant supernovae, and on the anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background.

See also

References

- ^ Wollack, Edward J. (10 December 2010). "Cosmology: The Study of the Universe". Universe 101: Big Bang Theory. NASA. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Will the Universe expand forever?

- ^ a b What is the Ultimate Fate of the Universe?

- ^ a b Lemaître, Georges (1927). "Un univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques". Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles. A47: 49–56. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49LTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) translated by A. S. Eddington: Lemaître, Georges (1931). "Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and increasing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extra-galactic nebulæ". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91: 483–490. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L. doi:10.1093/mnras/91.5.483Template:Inconsistent citations{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Did Einstein Predict Dark Energy?, hubblesite.org

- ^ http://www.pnas.org/content/96/8/4224

- ^ Dark Energy, Dark Matter

- ^ Ryden, Barbara. Introduction to Cosmology. The Ohio State University. p. 56.

- ^ WMAP - Fate of the Universe, WMAP's Universe, NASA. Accessed online July 17, 2008.

- ^ "The Return of the Phoenix Universe", Princeton Center For Theoretical Science. Accessed online April 15, 2009.

- ^ Glanz, James (1998). "Breakthrough of the year 1998. Astronomy: Cosmic Motion Revealed". Science. 282 (5397): 2156–2157. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.2156G. doi:10.1126/science.282.5397.2156a.

- ^ a b Y Wang, J M Kratochvil, A Linde, and M Shmakova, Current Observational Constraints on Cosmic Doomsday. JCAP 0412 (2004) 006, astro-ph/0409264

- ^ Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory (1997). "A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects". Reviews of Modern Physics. 69 (2): 337–372. arXiv:astro-ph/9701131. Bibcode:1997RvMP...69..337A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337.

- ^ Tegmark, M (May 2003). "Parallel Universes". Scientific American. 288: 40–51. arXiv:astro-ph/0302131. Bibcode:2003SciAm.288e..40T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0503-40. PMID 12701329.

- ^ Werlang, T.; Ribeiro, G. A. P.; Rigolin, Gustavo (2013). "Interplay Between Quantum Phase Transitions and the Behavior of Quantum Correlations at Finite Temperatures". International Journal of Modern Physics B. 27: 1345032. arXiv:1205.1046. Bibcode:2012IJMPB..2745032W. doi:10.1142/S021797921345032X.

- ^ Spontaneous entropy decrease and its statistical formula

- ^ Linde, Andrei (2007). "Sinks in the landscape, Boltzmann brains and the cosmological constant problem". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2007: 022. arXiv:hep-th/0611043. Bibcode:2007JCAP...01..022L. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2007/01/022.

- ^ Yurov, A. V.; Astashenok, A. V.; González-Díaz, P. F. (2008). "Astronomical bounds on a future Big Freeze singularity". Gravitation and Cosmology. 14 (3): 205–212. arXiv:0705.4108. Bibcode:2008GrCo...14..205Y. doi:10.1134/S0202289308030018.

- ^

- M. Stone (1976). "Lifetime and decay of excited vacuum states". Phys. Rev. D. 14 (12): 3568–3573. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..14.3568S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.14.3568.

- P.H. Frampton (1976). "Vacuum Instability and Higgs Scalar Mass". Phys. Rev. Lett. 37 (21): 1378–1380. Bibcode:1976PhRvL..37.1378F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.1378.

- M. Stone (1977). "Semiclassical methods for unstable states". Phys. Lett. B. 67 (2): 186–188. Bibcode:1977PhLB...67..186S. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(77)90099-5.

- P.H. Frampton (1977). "Consequences of Vacuum Instability in Quantum Field Theory". Phys. Rev. D15 (10): 2922–28. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..15.2922F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.15.2922.

- S. Coleman (1977). "Fate of the false vacuum: Semiclassical theory". Phys. Rev. D15: 2929–36. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..15.2929C. doi:10.1103/physrevd.15.2929.

- C. Callan; S. Coleman (1977). "Fate of the false vacuum. II. First quantum corrections". Phys. Rev. D16: 1762–68. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..16.1762C. doi:10.1103/physrevd.16.1762.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

- ^ S. W. Hawking; I. G. Moss (1982). "Supercooled phase transitions in the very early universe". Phys. Lett. B110: 35–8. Bibcode:1982PhLB..110...35H. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(82)90946-7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Will our universe end in a 'big slurp'? Higgs-like particle suggests it might". NBC News. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

Further reading

- Adams, Fred; Gregory Laughlin (2000). The Five Ages of the Universe: Inside the Physics of Eternity. Simon & Schuster Australia. ISBN 0-684-86576-9.

- Chaisson, Eric (2001). Cosmic Evolution: The Rise of Complexity in Nature. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00342-X.

- Dyson, Freeman (2004). Infinite in All Directions (the 1985 Gifford Lectures). Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-039081-6.

- Harrison, Edward (2003). Masks of the Universe: Changing Ideas on the Nature of the Cosmos. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77351-2.

- Penrose, Roger (2004). The Road to Reality. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-45443-8.

- Prigogine, Ilya (2003). Is Future Given?. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 981-238-508-8.

- Smolin, Lee (2001). Three Roads to Quantum Gravity: A New Understanding of Space, Time and the Universe. Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-1261-4.

External links

- Baez, J., 2004, "The End of the Universe".

- Caldwell, R. R.; Kamionski, M.; Weinberg, N. N. (2003). "Phantom Energy and Cosmic Doomsday". Physical Review Letters. 91 (7): 071301. arXiv:astro-ph/0302506. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..91g1301C. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.91.071301. PMID 12935004.

- Hjalmarsdotter, Linnea, 2005, "Cosmological parameters."

- George Musser (2010). "Could Time End?". Scientific American. 303 (3): 84–91. Bibcode:2010SciAm.303c..84M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0910-84. PMID 20812485.

- Vaas, R., 2006, "Dark Energy and Life's Ultimate Future," in Burdyuzha, V. (ed.) The Future of Life and the Future of our Civilization. Springer: 231–247.

- A Brief History of the End of Everything, a BBC Radio 4 series.

- Cosmology at Caltech.