User:OliverTwist88/Golden Team

The Golden Team Hungarian: Aranycsapat are also known as the Magical Magyars.[1]

The Golden Team (Hungarian: Aranycsapat; also known as the Magical Magyars, the Marvellous Magyars, the Magnificent Magyars, or the Mighty Magyars) refers to the record-breaking and world renowned Hungary national football team of the 1950s held in esteem to be one of the greatest national sides ever in international competition. It is praised, among other accomplishments, for being the team that re-invented football in the post-war World War II era. It is associated with several of the most notable matches of all time, taking part in four historically significant games of the 20th century, including the "Match of the Century", the "Battle of Berne", a semi-final with Uruguay and the "Miracle of Berne". Asserting maiden defeats on world powers England and Uruguay, one of the side's last unified actions consigned the Soviet Union to their first defeat at home mere weeks before a spontaneous national uprising against the Soviets changed the team's equation for unity.

The team's brilliance from the spring of 1950 lasted until its subsequent partial meltdown after the ill-fated 1956 Hungarian Revolution — a flashpoint in the Cold War and a strikingly heroic, moving and historically consequential event commonly viewed as having rent the first major blow against the panoply of the monolithic communist world. It is credited with directly leading to a kind of future tense football that opened a new chapter in the game's tactical scope for positional fluidity, thus rendering contemporary form and styles of the game outmoded. It introduced a powerful revolutionary ground game with its polyvalent quasi-4-2-4 offense and an early approximation towards the famous 360-degree "Total Football" strategy that later the Dutch football scene were synonymous with. The immediate heirs to Hungary's variant 4-2-4 tactical shape were eventual world champions Brazilian teams who adopted, emulated and enriched the Europeans' legacy for the 1958, 1962 and 1970 World Cups.

One of the most technically superb teams in history, by ratio of victories per game, tactical renovation, in company with its acclaimed matches, the side ranks as one of association sports' most dominant forces in the 20th century. As the definitive sporting force from the Eastern Bloc of the era, it was also a tool used by authorities in the propaganda war with the Cold War West, held up as emblematic of socialist ideals by virtue of liberating the genius that lay dormant in the proletariat. Its sporting prominence has been a topic of debate amongst postwar historians who note its measured influence on West German political and economic trends, and nationalistic streams of consciousness after one of the most celebrated World Cup competitions in 1954.

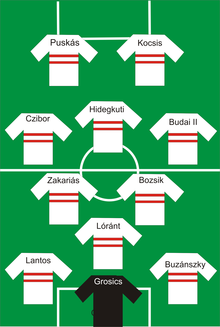

The ensemble could call on half-a-dozen world-class players within its cast, led by its talismanic captain Ferenc Puskás, prodigal goalscorer Sándor Kocsis, the deep lying centre-forward Nándor Hidegkuti, swift and sprightly winger Zoltán Czibor, great midfield choreographer József Bozsik who set the tenor for the tactical nous going forward and a first rater Gyula Grosics who tended goal. The incomparable attacking nexus of Puskás—Kocsis—Hidegkuti provided the Magical Magyars throughout their careers a windfall of 198 goals, Mihály Lantos, Gyula Lóránt, József Zakariás and Jenő Buzánszky modelled a good and oft-outperforming defense.

The extent of the Magyars' eminent domain and sojourn as giants of world football merits a closer visit of performances. Aside from a controversial 1954 World Cup final match that this article will later cover, Hungary on the world stage would suffer no defeats for 6 years, counting 42 victories and 7 draws — that lifts the side into the sphere of the truly remarkable. Another fact worthy of mention is the unique feat of attaining the strongest rating ever recorded in history using the Elo rating system for national teams (2166 points, June 1954). The constant and their essential hard currency was cogent offensive bandwidth within a six year 50 game period that leavened the sport with an astonishing 215 goals. It was around these 50 games that their golden age was framed.

'Socialist Football' and Advent of the "Playmaker"[edit]

The source of the intellectual firepower of the team at the managerial level began with Gusztáv Sebes, who had been a trade union organizer in Budapest and pre-war Paris at Renault car factories and thus was accorded a political clean bill of health to run affairs as the Deputy Sports Minister. He knead his socialist credentials to a new formulaic style that caused world football to witness "socialist football" in its prime — team game that would brush aside an assortment of individuals for six years to set milestones not set before or since. Sebes and his staff were keen to reference a new movement in football governed by the idea that a total cohesive solution with contours of players equally sharing in the ball's propagation were answers to soccer's future. This sketched the foreword and prelude, in a sense, to "Total Football" 20 years before the Dutch, where individual roles in zonal positions should not be strictly defined.

A lasting contribution of importance of the Magyars, in particular, involved the prototype advent of a crucial player that would put the game on a tactical furthering — the deep lying centre-forward. Into this total sum versatile solution (where players could shift and interplay other positions), Sebes laid his most influential centrepiece — a high value player unveiled for a groundbreaking role that caused Hungary to reform the game forevermore. Nándor Hidegkuti was set as a deep-lying free trading entrepreneur behind the twin beam of Puskás and Kocsis, known in football parlance as being "in the hole". This nuance of moving Hidegkuti off the main line put the game on a new course and into football's lexicon entered the fluid station called "playmaker". Opposing lines were unsteadied and pulled apart by this dual-purpose player by drawing a natural response and tendency from defenses to leave him un-marked and operate freely in space un-buffeted by not being amid the forwards. With event-driven spontaneity, Hidegkuti provided crashing sorties as ball movement dictated to crumble the centre goal area; and unlocked in the No. 9 position a new autonomous menacing robust character in football operating on the event horizon between midfield and the rearguards and between creator and goalscorer. Hidegkuti has been called the "father of total football" and was an astute navigator with 39 goals in 69 appearances. Thus this triune partnership of Puskás and Kocsis up front with a force-multiplier leveraged in Nidegkuti opened many doors of attack across inflexible defenses to obviate and subordinate all traditional systems.

Key Players: Ferenc Puskás, Sándor Kocsis, Bozsik[edit]

Certainly the "European Player of the 20th Century" and twice World Player of the Year (1952, 1953), Ferenc Puskás often enters the conversation of where the greatest footballers ought to be lodged in the pantheon of the last 100 years. The ever engaging and personable Ferenc Puskás was the most powerful striker Europe ever produced at 1st division football. He was also the greatest goalscoring international who ever lived. Undoubtedly, the most renowned and greatest of Hungarian sportsmen, he is likely in company with Harry Houdini and Ernő Rubik who lent his name to the iconic Rubik's Cube, for being the most famous Hungarian citizen of the 20th Century.

In a difficult rebuilding world of the postwar era, in the arc light and formative glow of emerging nascent mass media with a global reach and enhanced telecommunications, increasing networked newswires and live television coverage that meet audiences as never before, Puskás was football's first superstar both club level and in the world game predating the likes of Di Stéfano, Pelé, Johan Cruijff, Franz Beckenbauer, George Best, Diego Maradona, and Zinedine Zidane.

Oft-likened short, he was of modest proportions, rotund with muscular billiard ball table legs and average in-line speed but with deceptive acceleration. Puskás never did acclimate to using his nondominant right foot for much except to dribble and scored few goals with his head but more than made up with an on-field generalship and a deep cerebral reading of the game. He had a keen footballing brain to match his otherworldly accuracy. As anecdotal evidence would have, he had the intuition with extra sensory perception to know other sides' tactical nuances in less than 15 minutes of field play to orient his side as events unfolded. He exhibited a precocious talent at an early age, a capering dribble and heroic scoring indulgence from the ball from which he was impossible to separate by those defending in his presence. He is reputed to have been blessed with the most powerful drive ever cast from a left foot, an exclusive leaden snapshot that deftly tore through defenses with unerring precision. It is known that this great player scored 514 1st division-class goals and a total sum 1176 goals in a 24-year career. The main transformer of a great Hungarian squad into an exceptional one, Puskás was honored for being named the greatest 1st division goalscorer in the 20th century by the prestigious International Federation of Football History & Statistics (IFFHS) in 1995. Pelé was voted the most outstanding player of the century by the IFFHS with Puskás not far behind, ranking just behind Diego Maradona in the balloting.

A man with a touch of Midas in him, every team to which Puskás was attached as a captain and player were eminently the best in the world that seemed to prosper immensely from his seniority; profiting from an elegant yet fiery competitor with the sunniest of rough-diamond manners with a loud style who could seem to annex the most obdurate lines with brilliant expositions that sparkled nigh on goal. As captain of mighty Honvéd (for whom the majority of the national team's players played at club level), the greatest club side before the emergence of Real Madrid, and captain of Hungary, he was paired with the formidably talented and his near equal Sándor Kocsis. They were the greatest redoubtable scoring tandem that ever graced world football with 159 goals between them, vastly outdistancing all those that came before to put in place records that would be everlasting.

Later estranged from his homeland for many a good reason, but due in part, to the reprisals that were the fallout of the failed Hungarian Revolution and what might have awaited him for his refusal to return from abroad, the unusually apolitical Puskas was adrift in exile. On the wrong side of 30 and serving a one-year ban from FIFA, the man of large and joyous appetites and a heart spent on goodwill, was now out of shape and thought to be in the twilight of his playing days. Soon he found himself in the employ of the greatest club side in the world, Real Madrid at the height of its powers, to begin a second consecutive and stunning double career.

Facing a daunting challenge of learning a new language in the distinct new world of Francisco Franco's Spain, with the gift of confidence and the right mental attitude too, Puskás soon endeared himself to everyone around him. Most importantly, he gelled with on-field boss and great Argentine star Alfredo Di Stéfano, who was never the easiest man to know, tempermental cheek being part of his charm. Winning 5 Spanish championships along with way, Puskás again became a relevation, a four-time Spanish league-leading incandescent forward in legendary communion with Di Stéfano to positively form the basis for the greatest double act (as had been the earlier case with Kocsis) European club football has ever seen. While at Read Madrid, Puskás was considered the indispensable man of campaigns that saw Real Madrid win three UEFA European Championships and enlisted his help to be finalists on two other occasions.

As a player who was never bought or sold in his life, Puskás spent his entire career at the very top of his profession that seemed to raise his game to a sublime level. Puskás was central to the very heart of football history itself, having been involved in three of the most discussed matches of all-time: the "Match of the Century (where he scored twice), "Miracle of Berne" (the 1954 World Cup Final, where he scored once and had a picture perfect 87th minute poignant equalizer unjustifiably called offside), and Eintracht Frankfurt 3 vs. Real Madrid 7 (the 1960 European Cup Final where he scored 4 goals in what has been called the greatest and most famous European club match in history).

After the 1956 Uprising there were pockets of Hungarian expatriates in every major city in the West. While traveling with Real Madrid and beyond, he became a veritable consulate for members of these communities, ready to lend his support, financial or otherwise, to those who were in most need. Therein lies a Horatio Alger tale of a charitable man and player rising to the pinnacle of the game that began behind the Iron Curtain.

Many years before the team's arrival on the world scene, Hungary's Imre Schlosser merited high citation for having the most international goals with 59 since 1921. During the Magical Magyars' flowering, Puskás proceeded to famously break his countryman's world record in 1953, and Kocsis registered his 60th goal in just his 50th game in 1955, and Hungary boasted of fielding the no. 1 and no. 2 world record holders simultaneously. Kocsis was an authority in size, pace and note must be taken that his aerial prowess the world would come to see had no peer. Kocsis's 75 goals in just 68 games and his world record 6 hat tricks were only overcome by Pelé's 77 goals in his 92 matches. The Hungarian captain's superior count of 84 international goals in 85 games still is football's benchmark, unmatched by any top-flight player from the Americas, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

1952 Olympic Games (Yugoslavia vs. Hungary)[edit]

The avante-garde Hungarians arrived to the 1952 Summer Olympics to audition their strong command of the game in a grade that posed plenty already. In a little over 2 years unbeaten, their last 15 opponents were overlabored by 5.27 goals-per-game as most sides were wholly overwhelmed by the players astride the Danube. Scorelines of 5-0 and 6-0 were commonly seen and only a single team had defeated them in their 19 prior matches while victorious in 15. News travelled along the footballing grapewine that a vibrant, skillful and determined team's star from Central Europe was rising fast.

Already established was one of Europe's great sides, good press by the international news media gave Hungary high visibility outside the Iron Curtain to project a brand that yet the world at large had not see before. There great reputations were first made, and the highly entertaining men's football tournament proved to be a preview of coming attractions. With a mercurial corps of goalscoring forwards of Ferenc Puskás, Sándor Kocsis, and 'super-sub' Péter Palotás the team progressed through the field in a five-game attacking exposition scoring 20 goals. Those facing them could but tred lightly on their gapless blunting defense that allowed 2.

To run counter Hungary in the semi-final was a Swedish team, the 1948 defending Olympic champions heavily laden with talent, and a generally capable team that practiced the game skillfully. In a performance highly rated as one of their finest, a Ferenc Puskás first minute goal was the primer to a thoroughly emphatic game that served positive notice to the most influential circles in the European football community. Their 6-0 victory was of outgoing quality, and resonated most well with one especially. Tracking developments and viewing events on the field was Stanley Rous, secretary general of the English Football Association and future FIFA President, who praised his counterpart and extended a future invitation to oblige the Hungarians in Empire Wembley Stadium in England.

In the championship final, in front of 60,000 in Helsinki Olympic Stadium the Magyars made a stand against the world's No. 7 team — their neighbors to the south, with whom the Hungarian communist dictatorship on ideological grounds had strained relations. The team was beforehand politically instructed not to lose. The 1948 Olympic finalist Yugoslavian squad wore the makings of an emerging tier-one global player, the game given added spice by the intersection of politics and sport. The match against the Yugoslavs was a dearly fought one. Of the many foreign correspondents writing of the tournament was a young Spanish reporter who covered the Hungarians, he was no less than Juan Antonio Samaranch. Then penning for a Spanish daily, Samaranch was later to become the 20th century's most recognizable public spirit who cut a grandiose figure of the Olympic movement as the future President of the International Olympic Committee (1980-2001), and self-described enthusiast of the Hungarians' élan.

Late in the game, the Yugoslav backline was penetrated by Ferenc Puskás in the 70th minute, who nonchalantly put a short grounder past two onsetting defenders before goal, and winger Zoltán Czibor broke off from a direct line of action at flank with an additive goal at the 88th minute. Their 2-0 victory signaled their trajectory from a continental to that of a world power, and the sobriquet "The Golden Team" first became a popular term of endearment back in Budapest. The triumph of the Golden Team on on a patch of green grass, where joyous life and great freedom flourished to imitate art, was but a subset of a remarkable larger than life story of pushing the limits of human possibilities. Coincidentally, the 1952 Summer Olympics provided a brief but uplifting interlude of joy and pride for a small resilient nation of just over 9 and a half million seven years apart from the devastation and displacement of World War II before passing into the maws and orbit of a communist police state and into a highly restrictive society. Biding defiance to very long odds and most prospects, Hungary compiled an amazing and improbable Olympic record of managing to finish third in the medals table behind the vastly more prodigious United States and the USSR, earning 16 gold medals along with way with a total count of 42 of all colors. It underscored how much special importance the regime was willing to attach to a full commitment of sporting excellence and the political capital it would confer.

Central European Championship (Italy vs. Hungary 1953)[edit]

During this era, Hungary also partook in the Central European International Cup, a nations cup for teams from Central Europe and legal forerunner of the pan-European European championship. The competing field included Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy and Switzerland. After 5 years in production the 5th tournament culminated in a highly prized match between Hungary and a powerful Italian team.

Italy was, in many ways, the frontier and nursery for early European continental footballing ideas, in the 1930s made major strides to be at the center of all that was successful in European football, scaling the game's summit by gaining two World Cup honors consecutively in 1934 and 1938 (where Italy defeated Hungary 4-2 in the title game). The Italians were used to thinking seriously about the game and were partial to cultivating and nurturing defensive balance. Italian football was virtually the anti-pole to the offense-based polarity of the Hungarian temperament that viewed themselves as natural attackers. Indeed, one many of Italy's key contributions to the game had been proactive in modeling a highly organized backline that was intended to prevent goals. Europe's only enjoyer of World Cup success interfaced to the game with one of the planet's top indurate defenses that played to a very high standard, thought to be more than a match for those that traveled to meet them.

Italy's chosen style for stopping the wherewithal of opposing teams of foreign players, no matter how talented, from drawing good definition on their goal have been written about to give it credence. Outside a single notable defeat to England in 1948, the Azzurri had not competitively suffered a home defeat since days of Benito Mussolini in 1934, never surrendering more than 2 goals into their net in 36 home internationals, wearing an excellent undefeated record to always impose an onus and load visitors with care. Behind their only defeat to the English, the Italians furthered their senior squad that only 1 or less goals were allowed against their renowned backline in any home match that impress one the most. Hungary journeyed to the Rome and toward a foreign ambiance to play in the inaugural of Rome's newly re-designed famous Stadio Olimpico that presented itself as a dauntingly intimidating fortress of grandeur.

After opening ceremonies, a partisan audience of 90,000 were given perspective that put in relief the contrasting picture between the two teams: between Italy's garrisoned expression and presumably the world's top defensive unit contra the world's best frontline and Hungary's fluid and rhythmic carriage belying artfully crafted guile. The football world would see a irresistible Olympian force about to march against the immovable object — mere glimpses into the "Match of the Century".

The men of Italian football arrived in earnest with their reputed defensive superiority as had been known before and the outcome was defined on a hard compound of defensive ardor. By the later edge of the first half, the élan of the Hungarian front gainfully accosting the Azzurri defense began to stylistically unlimber it by a dialogue of passing from midfield to coax out the main Italian line exposing their rear to the rewardingly cast deep ball. A Nándor Hidegkuti goal at the 41st minute, and later two strong scores by Puskás in the second half, one a particularly telling late left-footed straight line drive from the top of the penalty box past a disbelieving Lucidio Sentimenti sealed memorable proceedings 3-0 in what was no mediocre achievement.

So irrepressible was Puskás not only to win, that while leading 2-0 late in the game, he exhorted his teammates for continued attacks and keeper Gyula Grosics to give him the ball at every opportunity, his attitude delighting Italian fans who though much of the wonderful football efforts they just witnessed. Respectful ovation descended on the Hungarian heroes, who were cheered off the field as victors of the tournament.

"Match of the Century" (England vs. Hungary 1953)[edit]

A match was arranged later that November in 1953 that would have game-changing implications to prevail upon old insular normative and complacent beliefs to inspire football theory onward. It would precipitate a re-shaping of new core footballing ideas and displace minimally for half a generation football's centre of gravity. To occur was an immensely fancied collision between the era's contemporary masters — the Magical Magyars and the venerable aristocrats of the game.

Ten days before their appointment with the English in the ancestral mecca of football, they played a good Swedish team in Budapest in a game that did not give rise to much confidence heading into the biggest match of their lives. Puskás missed from the penalty spot and hit the post, and the Swedes drew level in the 87th minute to earn a 2-2 draw. They were well sorted out and pilloried by the press and fans alike, but the result was sufficient for the squad to first pass a 19th century 1888-year Scottish benchmark of being undefeated in 22 international matches.

The English had invented the modern game in last half of the 19th Century. Its first laws and rules patented by a solicitor by trade Ebenezer Cobb Morley, and soon grew immensely popular across all spectrum of society due to its simple rules and minimal equipment requirements, being globalized as the world's most popular association sport in the last decades of the 19th century and early 20th centuries.

Since the codification of football in 1863 in Victorian England, the English national team had never suffered defeat on its home shores from foreign opposition from outside the British Isles, and their successful tradition had been penultimate and globally decisive. The old producers of football had turned aside every effort in 90 years to overcome the mightiest team of them all. This proud long reign of invincibility knit to semi-mythology was legendary, embedded into socio-national consciousness and ethos as a redoubt and post to which Englishmen could view with surety and confidence in spite of all forecasts, vicissitudes and the ever-changing times. Gorgeous, wonderful, and victorious English football possessed a feel of unbeatable quality and romantic neo-imperial Victorian inheritance with a direct unbroken connection to the palmiest days of the British Empire.

The British press, in building out the game that lay ahead, galvanized worldwide radio and newsprint audiences naming it the "Match of the Century", and a visit towards both teams' theoretical power, the media's remark of the match taking on world significance as "The World Championship Decider" — was a becoming view that was more attractive considering the acme strength of both nations. England was ranked No. 3 in the world with a rating of 1943 points or the No. 2 best team in the Old World (Argentina being ranked No. 2 with 2048 points), Hungary was ranked No. 1 with a rating of 2050* points. The anxiously promising match was ever England's sternest challenge to stem a gathering juggernaut from across the Channel from behind the Iron Curtain that had remained unbeaten for over three and a half years — and in deference to a remarkable tradition, un-trampled power in Europe, England would have its place in the sun again as the highly approved side.

England fielded a squad of prestige formed of considerable and legendary power within a time-tested and patently English tactical package (3-2-2-3 i.e. the WM formation) catalyzed at the Arsenal Football Club by gifted publicist and maverick manager Herbert Chapman in reaction to the Offside Law of 1925. It was composed of all the stars of League First Division, some of whom were of world renown and whose reputations were second to none. Two of whom would be later knighted for exceptional services rendered toward national British sport. These included a world-class football maestro, the ageless Sir Stanley Matthews who supplied much aerial and crossing prowess to set up goals where ever he traveled, a much feared powerful centre forward in Stan Mortensen who had scored 22 goals in 24 appearances, the famous Sir Alf Ramsey, a superb defender with special spatial awareness and technique, and their very capable centre-half captain Billy Wright, the first player in the 20th century to reach 100 appearances for a national side, for whom there is a modern ongoing push and current involvement by many to have knighthood conferred posthumously. At England's order was a very powerful midfield, a quadrangle of four players with an untiring work rate of fetching and carrying the ball up and down the field whom the Hungarians referred to as "the piano-carriers".

This highly successful system mated to a hardy, open, spontaneous and industrial style with its usually high quality personnel, united by a wondrous unmistakable English competitive spirit saw England take on all comers outside the Isles since 1901 and never have the world's finest left England victorious.

On a foggy Wednesday afternoon on November 25, 1953, in front of 105,000 in Empire Wembley Stadium and to millions of worldwide listeners and television viewers the "The Magical Magyars" mesmerized, the tactical mileage and individual skill sets between the two teams were seen and revealed immediately. Within the first minute, the whole English defense experienced variable geometric pressure invented out from midfield as the Magyars' startling attack proved insolvable with a new ground game that made lanes into England's stout stereotypical WM formation and exploited a flaw in their rigid marking system that opened yawning gaps by cleverly drawing defenders out of position. Nándor Hidegkuti could not be subdued. 45 seconds into the match, Hidegkuti ran down a centre seam, sold a feint thereby freezing Harry Johnson, diagonally angled inside and sent a rising 15-yard vector into the upper right corner of the net beyond the lunging mitt of goalkeeper Gil Merrick - quickly 1-0. Throughout the game Hidegkuti was un-markable in a starring role as he haunted the English line mixed with befuddling actions of Ferenc Puskás — a man who always seemed to move inexorably towards goal to drive in balls from all possible angles and distances — and the Hungarian line that posed tactical riddles by running interference for one another in interchanging their positions almost clairvoyantly on queue. These events left England in a nonplussed state, most especially centre-half Harry Johnston. Johnson was never assignment true in his dealings with Hungary's No. 9 Hidegkuti, unsure whether to accommodate him man-to-man or play zonally that caused him to be subtly adrift in a kind of no man's land that undone a large part of the English defensive posture.

A well-timed English counter-attack ensued that began in the penalty area, and down field Stan Mortensen released Jackie Sewell who put it past Gyula Grosics to restore order 1-1 at 13 minutes. But Nándor Hidegkuti fatefully scored again off a clearance that was treated poorly; and Ferenc Puskás became the world leader for most international goals via a seven-pass negotiation of the English defense, culminating in what many Hungarians call the "Goal of the Century". Puskás' famous "drag-back" goal imparted on him football immorality captured on film by executing a stunning piece of off-hand ball control from impromptu impulse that is a mainstay on classic highlight footage. It involved Puskás taking up position on the right-hand side of the six-yard box after receiving a less than perfect flat pass from right as Billy Wright barrels down to dispossess the escaping ball that drifts toward the dead-ball line. Puskás reflexively drags back the loose ball with the sole of his boot an instant before the arriving tackle, leaving the English captain finding empty space where the ball had been, de-cleated and nearly sprawled on his back. Puskás then pivots to find a ray of daylight between the near post and keeper Gill Merrick. The resultant Puskás cannonball between the crook of Merrick's left arm and the near post was shoehorned in to propel a 3-1 scoreline. Soon following was another Ferenc Puskás score — a deflected József Bozsik free-kick that burrowed into the net. Within 30 minutes the lead had swelled to 4-1, ten minutes of the restart the match's competitive phase was resolved.

In the second half, midfielder József Bozsik encroached a few feet outside the English penalty box and launched the ball airborne with a purposeful kick from 20 meters, it slowly climbing skyward on a wire as it hurtled just below the crossbar above a defender's head before he could blink. Hidegkuti — indelibly writing his signature on the game and author of England's maiden defeat — made his earnest entrance felt once again by one-timing a volley into goal off a lob before the ball came in contact with the ground, accomplished his famous hat-trick and crushed the paleo-tactics in worldwide application since 1925 at the whistle 6-3.

Of the many in attendance who would figure prominently in English football's future, one initially had taught mainland Europeans and the Hungarians a great deal about football, oft-slighted and under appreciated coach genius, 71-year old Jimmy Hogan. Hogan arrived with the youth team of Aston Villa to watch his colleague and friend Gusztáv Sebes play his game to the archetypal best that ran in the imagination of both. Hogan had been a pioneering journeyman coach, even a football missionary before the First World War who evangalized an elegant, almost esoteric knowledge of the game on the Continent and successfully coached Hungary's MTK into a league leader in the 1920s. Hogan was an outsider in English circles whose beliefs formed a minority view along with other of the same ilk, radical managers Sebes and Hugo Meisl of Austria for being a proponent of free flowing soccer where possession and therefore skillful passing sequences were keys to the game united to varying flexibility. The Hungarians dedicated their great triumph to the old man who had given them much. At game's end, Hogan commented that a new order in football had been shaped as dictated by the visting team - "...that was the football I've always dreamed of.."

The Magical Magyars' performance had been revelatory that seemed to presage a tactical revision of the game from static models to be the flexibility basis for much if not all that followed in the game. It focused a compelling case of inceptive modern football up against the dated pre-war operating system, as it peered toward a versatile new age that allowed players maximum freedom of movement. The match's value for the Magical Magyars' was inestimable as their magnum opus. For football itself, the panoromic prevision of how the future game would be played stimulated new ideas both within and outside the Continent, and minds started to change about the fluidity of the game, finding final value with the world champion Brazilian sides of 1958, 1962, 1970. The famous Wembley game of 1953 was a historical strategic and tactical watershed that made front-cover news in many countries, subject to acres of newsprint, informative scholarship and introspective self-analysis that has taken on a near mythical station in football lore — arguably being the 20th century's most influential match.

The 1954 World Cup[edit]

To a majority of vantage points, both inside and outside the game, Hungary's entry into the 1954 World Cup were to be a crowning for consummate achievement. Football world supremacy would be decided after the differentia between Hungary and that of football superpowers from faraway places in Latin America became known. The Magical Magyars were widely appraised by consensus as having the most tactically astute, redoubtable team to carry through these of aims with plenty of talent to match.

The 16 finalists were grouped in fours and only two would see the next round in the quarterfinals. Hungary shared Group B with Turkey, West Germany and South Korea.

On June 17, 1954 in Zurich, the Magyars opened their campaign against a debutant South Korean team, who were making their first journey to the World Cup finals. In spite of the Korean War's ending the year before, flights commercially out from Korea didn't exist, and the Korean players had to endure a tiring six-day odyssey by air, sea, road and rail to arrive to the tournament in Switzerland that added to their physical unrest. On less than a full day's recovery, the Koreans walked onto the field against uncompromising head wind. The pentameter of the Hungarians' mode of attack regaled spectators with a performance that was record breaking as the ball moved from strength to strength with a briskness causing so much movement that within twenty minutes half of the Korean team went down with cramps. At the 12th minute Puskás opened the floodgates to a torrential pastiche of goals. Inside forward Sándor Kocsis began his trek towards world fame with a tranche of 3 goals en route to a 9-0 win to set history's largest goal differential in the World Cup.

Three days later on June 20, 1954, the Magical Magyars went into action against one of their other group opponents, an unseeded and largely unfashionable West Germany squad of whom not much was expected in the competition. West German manager Sepp Herberger, imbued with a grander project to schedule his team for the best of chances to secure entry into the knockout stages, wittingly put out an under-strength squad to rest many his regulars and gain inputs to what made Hungary so impeccable. With a view to reconnoiter and have insight into Hungary's on-field strength while keeping his A-team fresh and his plans unexplored, informed his decision to play this gambit. It caused wide criticism back home in West Germany to the contrary. Herberger's contention was that Germany could still qualify for the quarter-finals in spite of a loss.

With crisp fine fettled precision, deft dribbling and colorful passing that would later define Brazilian football's joyous magic for decades, Hungary precipitated themselves against the opposing line and soon glode past bulwarks. To no one's surprise, a heavy programme of soccer assault ensued — the German half was the scene of most activity, their goal heavily leaned upon by a rolling fire and tactical rigor that attacked without interlude. Inside-forward Sándor Kocsis was like a cavalier man possessed, individually crashing through defensive mazes to dynamically wreck the Mannschaft defensive scheme into inchoate shambles with goals at the 2nd, 21nd, 68nd, 77th minutes.

This match also contains hues of controversy for the objectionable roughness out of normal calling imposed on the Hungarian captain, Puskás, who with a premium identity of being the world's greatest player, was now receiving some very special attention and ungentle marking from all comers he faced. The Hungarian Football Federation later would allege three critical fouls the match's refereeing missed undermined the tournament's officiating in part for the bellicose treatment Puskás was getting. Throughout the game, German defender Werner Liebrich was deputed to mark the indefatigable and high spirited Puskás, whose sparkling virtuosity at close quarters could publicly conquer the most obrurate defensive lines. At the height of the game with Hungary leading 6-1, Liebrich's challenge was the most devitalizing if not fateful tackle in the whole tournament as Puskás was on the end of a fiece tackle from behind; putting him provisionally out of the tournament with a sorely bruised ankle. The German goal buckled under a spectra of manoeuvers and to a parade of goals; the game ending very strong 8-3 for the Magyars, but the injury subtraction of Puskás would now throw its competitive future into question.

Hungary's other formidably talented star and Puskás' near equal, Sándor Kocsis was photogenic with a tall physique very much befitting star qualities of an actor whose skills were completely developed both on the ground and in the air. Now the suddenly very important Kocsis would gain his own renown in turn to be the leading content provider up front with notably helpful services of Hidegkuti and Czibor to marshal the side onward. Kocsis' personal mark, gaining 2.2 goals per game at the World Cup reverberates among football historians, who note is probably will remain forever unrivalled.

In West Germany, the public view on Sepp Herberger's decision to probe and not play Hungary at full array was a contentious issue with many demanding his resignation for not offering a truer challenge to the world's finest team. But regardless, Herberger's calculation worked as he had planned, Germany defeated Turkey 7-3 three days later in a requisite playoff to ensure passage into the final group of eight.

"Battle of Berne" (Brazil vs. Hungary 1954)[edit]

Football had come relatively early to Brazil, transmitted by the son of a British expatriate, Charles William Miller, who had attended the English public school at Southampton and brought the aristocratic collegian game with him in 1894 to São Paulo. Football was a cliquish pastime of British communities in urban areas of Latin America and after the First World War found a place in the national life of most South American nations across all segments of society. With credentials and a trim that were living at every World Cup, Brazil's emergence was one of a crescendoing work in progress. Their World Cup side of 1938 that managed come in third place showed prospects of untold potential. By the 1950 World Cup, as hosts of the World Cup, Brazil was primed on the cusp of destiny, receiving copious publicity as the highly advertised side ready to win over the world with a strong team of moment. Presented to a still-record audience of 199,850 in the world's largest and most futuristic Estádio do Maracanã, Brazil met in an unofficial "final" a much weaker Uruguayian team in a game that would haunt and mortify Brazilian regards on a national scale for a time. In a game that mattered most in what was the most famous match played up that time, Uruguay initially braced against Brazil's withering inertia and was down early 0-1. Late in the late, Uruguayan steely determination and arguably history's most famous counter-attack by Juan Schiaffino propelled Uruguay 2-1 again to the game's pinnacle.

Brazil came with a confidence and vaulting ambition that was made plain — to lift the chagrin and unhappy run of fortune of the "Maracanazo" that lingered with a team re-organized in a spirit to improve their circumstances after the 1950 fiasco. South America's top team again was at the door of greatness with a dispensation of balanced play that knew the game's trade on every level. The Seleção's rating of 2010 points reflected their status as the planet's No. 3 team; and were archetypal in elements of speed, physicality, and soulful passing and dribbling of superb Latin American football. Their backfield was led by the optimal defender Djalma Santos, perhaps the greatest right back in the game's annals and his colleague Nilton Santos worked in unison to underpin the strongest attacking fullback tandem in football history. Djalma Santos' virtues of a cool jockeying style was held in high esteem for the high rate of his dispossessions, tackles and stopping the perilous runs and passes of others. Both would play extensively together in 70 internationals, gain two World Cup honors and earn enormous credit in barring access to a well-rigged defence around goal. At the heart of Brazil's play stood one of midfield's greatest figures, Didi a "box-to-box" player to whom the ball was often channeled, After winning the 1958 World Cup, he would wear the title "world's greatest player". Around him were attached players of real talent.

The 1954 quarter-final between Brazil and Hungary was enthusiastically written about by the press covering the game as the "unofficial final". For fans, organizers, and journalists alike the match's ascent and buildout had finally arrived. Captaincy for the game with Puskás out injured was conferred on József Bozsik, the day's most gifted midfielder and the game's greatest winger Zoltán Czibor spelled Puskás at inside-left.

On June 27, 1954, even without their captain Puskás, the Magical Magyars summoned varsity effort and skill early. After three minutes, Nándor Hidegkuti took receipt of the ball from the left side of the penalty box. In a scramble for it, half the Brazilian team funneled to the area with the quickest of speed where pandemonium reigned before Hidegkuti mightily plowed into the ball with tremendous backlift through a wall of defenders to evoke high emotion in the 60,000 who had gathered. Mere minutes later, Hidegkuti momentarily dwelt on the ball before lofting an arch from midfield, and Kocsis out-leapt tight two-man marking to steer a long diagonal header into the net, 2-0 Hungary after 7 minutes. The proud Seleção was ill at ease by the jarring pace of the immediate scores imposed on them. Afterward, both teams strove in an attrition battle royal to stem the other's advance and curb developing plays through a policy that courted injury, unrelenting combative hard fouling that saw players clashing fiercely in contention for the ball amid palpable tension. The game became erratic with continual interruptions after each free kick was awarded; an unheard sum of 42 free kicks saw many piercing challenges lacking respect, some were violently brutal that reminds one of the wanton intensity on that fateful day. Of these, tripping that felled forward Indio in the penalty area was converted from the penalty spot by Djalma Santos, 2-1.

By the 60th minute, the match was 3-1 and seemingly out of reach for Brazil, who left nothing undone to keep within the match. Shortly afterwards, Julinho slalomed in to stroke a curling drive, the ball knuckling into the top right corner of the net from the opposing side of the penalty box in one finest speculative efforts seen at the tournament, 3-2. József Bozsik, a deputy member in the Hungarian Parliament took umbrage and feeling that he was tackled unfairly retaliated by punching Nilton Santos and soon both were in fisticuffs and expelled. Brazil energetically surged forward with their remaining stores, but Didi hit the crossbar in what would be their last chance to draw level. But there was trouble elsewhere on the pitch. Djalma Santos put aside all ideas of playing football to pursue Czibor about the field livid in a fit of rage, who undaunted in the final minutes of the game was seen streaking down the field's periphery and shuttled a well-flighted ball to the centre goal area to a lone Sándor Kocsis, who with his head fiercely smashed in the final score 4-2.

The last moments of the game was little more than a running sparing match between the two great teams. Brazil forward Humberto Tozzi kicked Hungary's Gyula Lorant prior to the whistle and was genuflect on bended knees not to be sent off by referee, Arthur Ellis, who doled out the game's third red card. As the game concluded, the excesses and tensions on the field continued unabated off of it that ended in emotional turmoil. Wild rumors broke and circulated that a spectating Puskás allegedly struck Pinheiro with a bottle causing a three-inch cut, while most reports hold a spectator culprit not the Hungarian captain. Hamstrung throughout the game, an incensed Brazil gave vent by having their fans, photographers, trainers, reserve players and coaches invade the pitch with the Swiss police powerless to impose rule on the tumult and disorder that followed. In the tunnel of the stadium, Brazilian players smashed the light bulbs leading to the Hungarians' dressing room and ambushed the Magyars in their quarters where a melee in virtual darkness occurred, there broken bottles, fists and shoes were used as weapons. At least one Hungarian player was rendered unconscious and manager Gusztáv Sebes ended up requiring four stitches after being struck by a broken bottle.

Many year later, the game's English referee Arthur Ellis commented: "I thought it was going to be the greatest game I ever saw. But it turned out to be a disgrace."

"Never in my life have I seen such cruel tackling."- observed The Times correspondent.

The infamous occasion of the "Battle of Berne" is still talked about today among the old timers in Hungary, with many expressing the opinion that this was the first "final" of the three that Hungary had to play at the 1954 World Cup. It has also been put forward that the Magyars' achievement staved off and prevented Brazil from beginning their procession of World Cup titles in 1954, added to those of 1958, 1962, and 1970.

"The Greatest Game Ever Played" (Uruguay vs. Hungary 1954)[edit]

In the early part of the 20th century, up to and including 1954, Uruguay dominated international football in South America. A nation of a mere three million was disproportionately per capita the most successful football nation in the world. Running in parallel with how football developed in Latin America, a sport institutionalized in society and its cultural life after pockets of British expatriates had exported the collegiate game all throughout the Anglosphere and beyond, Uruguay rapidly made itself known on the world stage before its larger neighbors could catch them, and was prominent in establishing South America as a coequal centre of the game.

- to still be written

"The Miracle of Berne" (1954 World Cup Final, West Germany vs. Hungary)[edit]

The background[edit]

The media establishment wrote about an incontestable team forged in the heat of innumerable sessions of practice about to meet a collection of psuedo-amateurs from West Germany that did not have a yet true national league of their own. Hungary had advanced to an astonishing record of 34 wins, 6 draws, and 1 defeat since August 5 1949, and were registers of a consecutive unbeaten run in their last 31 matches that had gradually gotten stronger within a record 4 years and 1 month. Teams that came across them in these matches paled in comparison; most were over-extended by percussive fast-moving tensions of genius that treated the ball beautifully to find pathways and equations with selectively tailored passes as they succumbed to a crushing rataplan of 4.46 goals-per-game. The old firm around Gyula Grosics earnestly had a star quality about it too. Before Gordon Banks and Lev Yashin there was Grosics. He was Europe's most noted and gifted goalkeeper since the Spanish Ricardo Zamora and a fine athlete in the goalkeeping arts. Those around him, to a man, gave account with fine defensive skills to horizontally engage and deflect onsetting plays made against them (allowing 1.15 goals/game); the team seeming to catalyze some sort of footballing perfection.

The Mighty Magyars's 41 game narrative had staged coups that had far and wide implications for the game itself. They rendered theory into reality with a quantum leap reformation of the game that seemed to channel the spirit of the modern age. They played everyone worth playing and carried all before them by the alliance of skill and imagination and a plentitude of power to overwhelm in every department. Within a span of two years, the Olympic and European champions had crushed teams with four World Cup titles between them, had humbled the masters of the game England 6-3 abroad and 7-1 at home. Both great South American finalists of the 1950 "Maracanazo" (the 1950 World Cup Final), mighty Brazil and the virtually unassailable world champion Uruguay were solidly beaten and eclipsed 4-2 by a stronger wording of power.

The Hungarians' 8-3 victory over West Germany at group stage was seen as a dress rehearsal to a level of expertise Hungary would bring against a West German side that was starting to really surprise many. The championship match, apparently, were to be a mere fixture in formality Hungary were to visit to assume their rightful place as the greatest football side that ever was. Main thoughts were that West Germany were to face the planet's best team framed to their finest hour: the cavalier outpouring of Kocsis, who had scored 13 goals in the last 5 games and who entered the Final with 48 goals in 40 appearances allied to the newly chartered playmaker position and wiles of the seasoned campaigner Hidegkuti, and the game's fastest winger Zoltan Czibor who did brisk trade with his positive buccaneering end runs on the periphery. József Bozsik was their playing conscience and metronome from midfield, and under his baton the Hungarians had flourished.

A veritable media blitz and big drama surrounded the world's greatest goalscoring international, namely Puskás', whose fitness was the main focus of attention. He had not played since the first German game, where they won 8-3. On everyone's mind and the great sought after question of the tournament now became whether Puskás was hale and able to naturally play free of injury. It was most often queried by the press, and reports vacillated back and forth on whether the great star's ankle had healed properly. Since Puskas' withdrawal, Sandor Kocsis was at the cynosure of all eyes and the constant target of unending two-man coverage of teams who sought to protect themselves, sending willing trackers to hang off the shoulders of the much lionized forward wherever he went. Sebes figured to draw off some of that attention. Perhaps where hugely popular sentiment overruled pragmatism, it was the day before the match where Puskás was given a fitness exam by the medics and cleared to play. Even at "80%" per manager Sebes he was optimally more than a match than virtually anyone, entering the final with a astonishing 68 goals to his credit in 57 matches to furnish the exclamation. The team received a copious amount of letters and telegrams from well-wishers from everywhere where Hungary supporters lodged.

Sepp "Boss" Herberger was appointed national manager of the German team in 1936 during the height of Nazi Germany, perhaps himself out of careerism joining the incumbent party in 1933. Later rehabilitated after the war for his political sympathies, found himself back at the top post, there tasked in re-buildig the West German national side in 1950, a position he would hold until 1964. Always one to dispense pearls of wisdom to his players, with the desired discipline he build his national side around the significant talents of one of his best players, goalscoring midfielder Fritz Walter. Walter had been in detention in 1945 and was on the verge of being transferred to a Soviet gulag with the general German prisoner of war population when a stranger's providential intervention rescued both his life and destiny to captain the West German side. Some years before, a Hungarian spectator recalled seeing Walter play for Germany, and the impressive sight was sufficient for him remembering after these many years. The Hungarian prison guard mis-directed the Soviet captors to the notion that Walter's real identity was Austrian and that he was not a Germany national.

Herberger fashioned messages of stamina, strength, diamond-hard determination and preparedness that very much took hold in his players, who would in turn forever sculpt and hew out these exemplar virtues on the soccer field for German football. German players were beholden to Herberger, their headmaster, ever puritanical, a monumental mason of character and team-building traits his players living proof, having now achieved a reputation in Germany akin to that of an eminent war-strategist. The German master patiently watched and gained inputs, studying the great Hungarian team until he felt he understood them. The Hungarians' great 6-3 triumph over England a year earlier had been put to film, the Germans put in homework in pouring over meticulous details anxious to do better than the English. Herberger himself had a original close viewing of Hungarian tactical maneuvers in their own 3-8 defeat at group stage, and came off ever more informed than before.

The party opposite had Gusztáv Sebes, ever the stylist, thinker, innovator, culturally permissive to the end that Puskás practically ran affairs both on an off the field, presiding over a dream squad of the most elevated players and illustrated what it was to play the game properly as a vision of joy and perfection. The duel between the two grandmasters also extended onto the field, finding two sentimental favorites and protagonists in captains Fritz Walter and Puskás.

Hungary, on the page, entered the world championship decider the sport's No. 1 team with the highest ranked football squad in history. West Germany, who entered the tournament unseeded as the No. 7 team, after their crushing 3-8 defeat to Hungary, took a more path less travelled to converge on the final and was soon aroused a different team -- embarking on a seriously improbable campaign that intrigued and confounded most pundits and foreign correspondents that saw them. After their loss, the Germans routed the Turks 7-3 in a requisite playoff win, and proceeded to earn big upsets over Yugoslavia (2-0) and Austria (6-1) to reach the final as German players harnessed an inner source of gripping esprit, vitality and an unfeigned singleness of determined purpose. Many German players held day jobs and some had returned from Allied captivity as prisoners of war, and few could properly locate the reasons for the amatuers' marvellous form that was in peak condition. The strength of each German player seemed reborn.

The eve of the match was anything but restful for the Hungarians who still needed the right amount of recuperation after two devitalizing matches against arguably the world's two foremost teams had taken a step out of their great players. Outside their hotel were Swiss brass bands practicing unfavorably for the Swiss national brass-band competition complete with parades that seem to live on until two o'clock the next morning, and denied many players the rest they so needed. The Hungarians had much explaining to do in trying the gain entry to Wankdorf Stadium during match day. The stadium was full and charged with an electrified atmosphere under a tight police presence. The Germans' team bus that preceded theirs received passage inside, the Hungarians' bus was obliged to park outside with the players having to wade through heaving crowds to make their way in. That left manager Sebes explaining to Swiss police that they were one of the match's arriving teams, and was met by the heavy end of a policeman's rifle butt for his persuasion.

Once inside, there occurred a memorable championship match still very much discussed in Germany and Hungary. The stirring sporting performance would be legendary, for the players the game of their lives. Beyond, it is generally thought of as the most influential championship sporting encounter of the 20th century that would have ramifications of macro-historical significance for the transformative political and economic climate the verdict would foster in both countries and in postwar Europe.

The Match[edit]

As the United States of America was in the midst of holiday-making during its Independence Day celebrations, the World Cup Final on July 4th 1954 in Berne a half a world away would be the highest rated international match ever played in history. Some 30,000 West Germans had crossed the Swiss border to live vicariously through their team, whereas few Hungarians were permitted to travel abroad. Wankdorf stadium was filled beyond capacity, attendance stood at 65,000, what few Hungarians were present were crowded out by the prodigious German presence.

Prior to the match, clouds had broken sending a downpour that seem to portent the unpredictable nature of the day's proceedings, raining mightily all day prior to kickoff. The playing field was thus a sluggish alluvial quagmire marked by lots surface water that would radically alter the game's complexion and personality. The weather-worn muddy and heavy conditions would soak up the true pace of the Hungarians' superior technical skills, whose beauty in action and playing mannerisms would diminish by many shades. The Germans had decisively beaten Austria 6-1 under similarly situated weather conditions in their semi-final match and had excelled, doggedly keeping at such slogging affairs with a penchant for winning. German captain Fritz Walter personally had thrived throughout his career and served his country nobly when rainy weather was a factor. He was now in his element, "Fritz Walter Weather" a phrase which had been around for a while was back in popular use. There were some initial discussion by organizers to re-schedule the game when it decided to continue as usual.

It would be the old incomparable nexus of Puskás, Hidegkuti, Kocsis down the center forward line, on the slightly receding wings Mihály Tóth on the left, and Zoltan Czibor was acquainted with a new station at wide right where he'd never played before at national there to unsettle and stress left-back Werner Kohlmeyer, who apparently suffered from a lack of pace. The Mannschaft's steering board queued Max Morlock, Helmut Rahn, Hans Schäfer and Ottmar Walter who accrued 15 goals in their 5 matches, Ottmar's brother Fritz would be the hub around which their tactical machinery revolved. The Germans, flushed with an enthusiasm from the tonic of their two proceeding victories, had scored 4.4 goals-per-game in the tournament as rated against the 6.25 goals-per-game of the Mighty Hungarians. Briton William Ling did the officiating with his assistants Welsh Benjamin Griffiths and Italian Vincenzo Orlandini meandering the sidelines.

As had been often the case in their matches, it was with capital effort that the Hungarians initiated affairs early. Barely inside of 6 minutes, the ball was propogated and placed to Sándor Kocsis feet, who turned upfield and was inside the center Germany penalty area when he jettisoned a hard shot aimed to the left of keeper Toni Turek. The ball met the hindquarters of a German player and was sent deflected wide left uncollected to a ideally situated forward player. The bouncing ball there met the menacing left foot of Puskás, who with a clinical touch stamped in the first score from an angle behind Turek, 1-0. Puskás raised his arms triumphantly to the adulation of his team's supporters and a jubilant congregation crowded around the great star. Everything seemed to go expectedly perfectly and sublime. Barely two minutes later, the sum of all fears in the judgement game for the Mannschaft and a nation of 60 million listening on radio came into tangible being and visibility.

Again it was Sándor Kocsis who appeared to be everywhere on the pitch, this time again in the Germany penalty area doing hard battle for possession and was fast nearing the 6-yard box. It was Werner Kohlmeyer, under duress, who thought it wise to back-pass to keeper Turek to reset the match in the face of Kocsis' foray. A momentary lapse of coordination by 35-year old Turek cause the slick ball to be mis-handled as it popped loose just inches from his hands. Eyeing the ungathered gift was Zoltán Czibor who sprung it free into the open mesa, wheeled around horizontal to the goal to get a full square view at the empty net and sent spasms of angst and great joy throughout those in attendance and those many millions listening on radio as the ball rolled into the vacant German net. 2-0 Hungary within 8 minutes. Czibor ran to meet this compatriots his right arm raised in bouyant elation. A rout similar to their earlier 8-3 win was beginning to take shape, the writing on the wall appeared to be in the making — Hungary would indeed be world champions.

The German players, ever mindful of the match's significance, did not buckle when it mattered most, seeing Hungary striving to weave triagular patterns over the field that quite did not hold up to scrutiny on adverse field conditions. A technical innovation had reached the Germans. Fledgling sports apparel company Adidas had supplied them with a revolutionary footwear, a technological breakthrough -- a boot design that had exchangeable, screw-in studs that could be adapted to any weather. The Germans quickly demonstrated these manifest advantages of truer traction with braver, faster team movement and the steady suriety of their footing.

International Football's All-time Highest Ratings[edit]

The following is a list of national football teams ranked by their highest Elo score ever reached as of July 16, 2010.

| Rank | Nation | Points | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2166 | 30 June 1954 | |

| 2 | 2153 | 17 June 1962 | |

| 3 | 2140 | 11 July 2010 | |

| 4 | 2117 | 3 April 1957 | |

| 5 | 2106 | 15 August 2001 | |

| 6 | 2100 | 6 July 2010 | |

| 7 | 2099 | 4 September 1974 (as West Germany) | |

| 8 | 2079 | 20 July 1939 | |

| 9 | 2046 | 1 September 1974 | |

| 10 | 2041 | 22 October 1966 | |

| 11 | 2035 | 13 June 1928 | |

| 12 | 2023 | 9 October 1983 (as Soviet Union) | |

| 13 | 1999 | 27 June 2004 | |

| 14 | 1998 | 31 May 1934 | |

| 15 | 1983 | 15 November 2000 | |

| 16 | 1967 | 11 July 1998 | |

| 17 | 1962 | 25 June 1998 (as FR Yugoslavia) | |

| 18 | 1960 | 13 June 1986 | |

| 19 | 1953 | 10 March 1888 | |

| 20 | 1950 | 25 June 1950 |

International Football's Highest Rated Matches[edit]

The Mighty Magyars feature in three of the top 10 highest rated matches all-time. A list of the 10 matches between teams with the highest combined Elo ratings (the nation's points before the matches are given) as of July 16, 2010.

| Rank | Combined points |

Nation 1 | Elo 1 | Nation 2 | Elo 2 | Score | Date | Occasion | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4211 | 2100 | 2111 | 0 : 1 | 2010-07-11 | World Cup F | |||

| 2 | 4161 | 1995 | 2166 | 3 : 2 | 1954-07-04 | World Cup F | |||

| 3 | 4157 | 2050 | 2107 | 2 : 1 | 2010-07-02 | World Cup QF | |||

| 4 | 4148 | 2068 | 2080 | 0 : 1 | 1973-06-16 | Friendly | |||

| 5 | 4129 | 2085 | 2044 | 1 : 0 | 2010-07-07 | World Cup SF | |||

| 6 | 4119 | 2050 | 2069 | 1 : 0 | 1982-03-21 | Friendly | |||

| 7 | 4118 | 2108 | 2010 | 4 : 2 | 1954-06-27 | World Cup QF | |||

| 8 | 4116 | 2141 | 1975 | 4 : 2 | 1954-06-30 | World Cup SF | |||

| 9 | 4113 | 2079 | 2034 | 2 : 1 | 1974-07-07 | World Cup F | |||

| 10 | 4108 | 2015 | 2093 | 1 : 1 | 1977-06-12 | Friendly |

Golden Team Alumni[edit]

Curriculum Vitae, Records & Statistics[edit]

- World Record: (June 4, 1950 to Feb 19 1956) 42 victories, 7 draws, 1 defeat ("Miracle of Berne") - 91.0% winning percentage ratio.

- Team Record (June 4, 1950 to July 3, 1954) 32 game undefeated narrative, broken on June 14, 2009 by Spain.

- World Record: strongest power rating ever attained in the sport's history using the Elo rating system for national teams, 2166 points (set June 30, 1954). This standout distinction yet stands unequalled. Brazil ranks No.2 behind Hungary with a theoretical power rating of 2153 points (set June 17, 1962). Argentina set the third highest Elo rating of 2117 points on April 3, 1957, followed by France (high: 2106 pts. Aug. 15 2001).

- World Record: most consecutive games scoring at least one goal: 73 games (April 10, 1949 to June 16, 1957).

- World Record: longest time undefeated in 20th and 21st centuries: 4 years 1 month (June 4, 1950 to July 4, 1954).

- World Record: most collaborative goals scored between two starting players (Ferenc Puskás & Sándor Kocsis) on same national side (159 goals).

- World Record: Hungary manager Gusztáv Sebes holds the highest ratio of victories per game past 30 matches with 82.58% (49 wins, 11, draws, 6 defeats). Brazil legend Vicente Feola (1955–1966) owns the second highest with 81.25 (46 wins, 12 draws, 6 defeats).

- World Cup Record: 5.4 goals-per-match in a single World Cup finals tournament.

- World Cup Record: +17 goal differential in a single World Cup finals tournament.

- World Cup Record: 2.2 goals-per-match average for individual goal scoring in a single World Cup finals tournament (Sándor Kocsis 11 goals in 5 games).

- World Cup Record: highest margin of victory ever recorded in a World Cup finals tournament match ( Hungary 9, South Korea 0 - July 17, 1954).

- World Cup Precedent: first national team to defeat two-time and reigning World Cup champion Uruguay in a World Cup finals tournament (Hungary 4, Uruguay 2, semi-final — July 30, 1954).

- World Cup Precedent: Sándor Kocsis, first player to score two hat tricks in a World Cup finals tournament (Hungary 8, West Germany 3 - July 20, 1954 & Hungary 9, South Korea 0 - July 17, 1954).

- National Record: Equalled highest margin of victory recorded by Hungarian national team (Hungary 12, Albania 0 - Sept. 23 1950).

- Olympic Precedent: first national side from behind the Iron Curtain to win the men's Olympic football tournament (Hungary 2, Yugoslavia 0 Aug. 2 1952 Helsinki)

- Precedent: first national side in the world to eclipse a 1888 Scottish record of being undefeated in 22 consecutive matches (32 games).

- Precedent: first national side from outside the British Isles to defeat England at home since the codification of association football in 1863, a span of 90 years (Hungary 6, England 3, see "Match of the Century" - Nov. 25 1953).

- Hungary's 7-1 defeat of England in Budapest the next year is still England's record defeat.

- Precedent: first non-South American national side to defeat Uruguay (Hungary 4, Uruguay 2, semi-final — July 30, 1954), breaking a 17 game Uruguayan unbeaten run against non-South American competition dating from May 26, 1924.

- Precedent: first national side to defeat the Soviet Union at home (Hungary 1, Soviet Union 0 - Sept. 23 1956).

- Precedent: first national team in history to simultaneously host the No.1 and No. 2 world record holders for most goals scored internationally (Ferenc Puskás 84 goals, Sándor Kocsis 75 goals) from May 11, 1955 to October 14, 1956.

- Team Record vs. Elo Ranked Opponents: (June 4, 1950 - Oct. 14 1956), vs. world Top-10 ranked opponents: 11 wins, 2 draws, 1 loss / vs. world Top 5 opponents: 4 wins, 0 draw, 1 loss.

Honours[edit]

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Football | ||

| 1952 Helsinki | Men's Football | |

- Olympic Champions

- 1952

- Central European International Cup

- 1948/53

- World Cup

- Finalist 1954

References[edit]

- ^ Rogan Taylor, ed. (1998). Puskas on Puskas: The Life and Times of a Footballing Legend. Robson Books. p. 12. ISBN 1861051565.

- Rogan Taylor, ed. (1998). Puskas on Puskas: The Life and Times of a Footballing Legend. Robson Books. ISBN 1861051565.

- Terry Crouch, ed. (2006). The World Cup: The Complete History. Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 1845131495.

- Michael L. LaBlanc & Richard Henshaw, ed. (1994). The World Encyclopedia of Soccer. Invisible Ink Press. ISBN 0810394421.

External links[edit]

- Aranycsapat - dedicated web page

- Gusztáv Sebes biography

- Hungary's Famous Victory

- Dr. Gerő Cup 1948-53

- National football teams' rankings

Category:Hungary national football team

Category:Nicknamed groups of association football players