Userkaf

| Userkaf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Userkaf, Usercheres (Manetho) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Head of Userkaf, recovered from his sun temple at Abu Gurob | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2494 – 2487 BC[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Shepseskaf or Djedefptah? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Sahure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Sahure, Khamaat[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Khentkaus I? Raddjedet (myth) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2487 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid of Userkaf | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 5th Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Userkaf (meaning "his soul is strong" or "his Ka (or soul) is powerful"[4]) was the founder of the Fifth dynasty of Egypt and the first pharaoh to start the tradition of building sun temples at Abusir.[5] He ruled from 2494 to 2487 BC[1] and constructed the pyramid of Userkaf complex at Saqqara.

Family

Userkaf may have been a grandson of Djedefre by his daughter, Neferhetepes.[6] His father is unknown, while some believe his mother to have been Khentkaus I (or his wife before he inherited the throne).[7]

Another of Userkaf's wives was the similarly named Queen Neferhetepes, known to be the mother of Sahure.[8][9] Userkaf may also have been the father of Neferirkare Kakai, a son by Khentkaus I.

Another less common view, in concordance with a story of the Westcar Papyrus, is that the first three rulers of the fifth dynasty were brothers—the sons of a woman named Raddjedet.

Thus, Sahure, Userkaf's successor was most likely his son. Furthermore, a strong argument in support of the theory that the first four kings of the fifth dynasty were closely related is that we know several officials who served as priests in the funerary cults of several of these kings:

- Tepemankh, priest of the funerary cults of Userkaf and Sahure;[10]

- Senuankh, another priest of the funerary cults of Userkaf and Sahure;[11]

- Pehenukai, priest of Userkaf's cult and vizier during the reigns of Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai;[12]

- Nikaure, judge, palace official and priest of funerary cults of Userkaf and Neferefre;[13]

Reign

Length

The exact duration of Userkaf's reign is unknown. Userkaf is given a reign of seven years by the Turin Royal Canon while Africanus states that Manetho's Epitome attributes him 28 years of reign. The Palermo stone describes the year of the third cattle count under Userkaf, which would correspond to his sixth year on the throne as the cattle count was generally, but not necessarily, biennial during the Old Kingdom. Analyses of the space available on the Palermo stone between this date and Sahure's register indicates that Userkaf did not reign longer than 12 to 14 years.[14] In his comparative study of the fragments of the Palermo stone, Georges Daressy concluded that Userkaf reigned about 10 years.[15] This figure is considered more plausible than Manetho's 28 years given the monumental remains dating to his reign. Four mentions of the "year of the fifth cattle count" were also found in Userkaf's sun temple,[16] which could indicate that Userkaf reigned for at least 10 years. However, these inscriptions are incomplete, in particular the king's name is lost, so they may refer to the reign of Sahure or Neferirkare[17] rather than that of Userkaf.

Activities

Nikaankh, an official during Userkaf's reign, had a royal decree of Userkaf reproduced in his mastaba. By this decree, Userkaf donates and reforms several royal domains in middle Egypt for the maintenance of the cult of Hathor.[18] Apparently, Userkaf also started the temple of Monthu at Tod, where he is the oldest attested pharaoh.

Userkaf's reign might have witnessed a recrudescence of trade between Egypt and its Mediterranean neighbors thanks to a series of naval expeditions, which are represented in his mortuary temple.[19]

Monuments

Sun temple

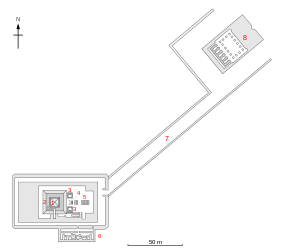

Userkaf's most innovative monument is undoubtedly his sun temple at Abu Gorab. First recognized by Richard Lepsius in the mid-19th century, it was studied by Ludwig Borchardt in the early 20th century and thoroughly excavated by Herbert Ricke in 1954. According to the royal annals, the construction of the temple started in Userkaf's 5th year on the throne and, on that occasion, he donated 24 royal domains for the maintenance of the temple.[20] The site of Abusir may have been chosen due to its proximity to Sakhebu, a locality mentioned in various sources such as the Westcar Papyrus as a cult center of Re. Userkaf's sun temple covered an area of 44 × 83 m[21] and was called

| |

Nḫn Rˁ.w, The fortress of Ra.

It is believed[22] that the construction of the sun temple marks a shift from the royal cult, so preponderant during the early 4th dynasty, to the cult of the sun god Re. The king was not revered directly as a god anymore but rather as the son of Re and this, in turn, changed the royal mortuary cult.

In this context, the sun temple, oriented to the west, was a place of worship for the setting (i.e. dying) sun and was thought of as a part of the royal mortuary complex. For this reason, the sun temple shares many architectural elements with the pyramid complex itself: it comprises a high temple build around a large obelisk and a causeway leads to a rectangular valley temple, close to the Nile. However, the valley temple is not oriented to any cardinal point and the causeway is not aligned with the axis of the high temple, both features being highly unusual. The view that the sun temple and pyramid complex were nonetheless considered similar is supported by the Abusir Papyri[23][24] which indicate that the cultic activities taking place in the sun temples were closely related to those of the royal mortuary complexes. This new ideology of kingship lasted for most of the fifth dynasty since six out of seven of Userkaf's immediate successors constructed sun temples in Abusir as well.

Bust

A bust of Userkaf was discovered in his sun temple at Abusir and is now on display at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. The head of Userkaf is 45 cm high and carved from greywacke stone. The sculpture is considered particularly important as it is among the very few sculptures in the round from the Old Kingdom that show the monarch wearing the Deshret (Red Crown) of Lower Egypt. The head was uncovered in 1957 during the joint excavation expedition of the German and Swiss Institutes of Cairo. A second statue of Userkaf, now conserved at the Egyptian Museum, was found in his pyramid complex at Saqqarah. It is a colossal head wearing the nemes headdress in red granite of Aswan.

Pyramid complex

Contrary to his probable immediate predecessor, Shepseskaf, Userkaf built a pyramid for himself at Saqqarah, close to Djoser's pyramid complex. Since the complex seemed to have been finished, it is posited that Userkaf's reign must have been longer than the 7 years credited to him by the Turin canon.

Contemporary adaptions

Egyptian Nobel Prize for Literature-winner Naguib Mahfouz published a short story in 1938 about Userkaf entitled Afw al-malik Usirkaf: uqsusa misriya. This short story was translated by Raymond Stock as King Userkaf's Forgiveness in the collection of short stories Voices From the Other World.

See also

References

- ^ a b Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 480. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ a b c d e Userkaf accessed April 29, 2012

- ^ Peter Dorman: The biographical inscription of Ptahshepses from Saqqara: A newly identified fragment, Journal of Egyptian archaeology A. 2002, vol. 88, pp. 95–110 [16 pages], summary available here

- ^ Clayton, Peter. Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1994. p. 61

- ^ Quirke, Stephen (2001). The Cult of Ra: Sun Worship in Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 127

- ^ Ian Shaw The Oxford history of ancient Egypt p.98

- ^ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson, 2004. p.65

- ^ Archaeogate Egittologia: Sahure's Causeway Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Clayton, p.61

- ^ Cf. K. Sethe Ch.1 § 19

- ^ Cf. K. Sethe. Ch. 1 § 24

- ^ Cf. K. Sethe. Ch. 1 § 30

- ^ Cf. A. Mariette, p. 313

- ^ Cf. J.H. Breasted § 153-160, p. 68–69

- ^ Georges Daressy

- ^ Miroslav Verner: "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology". In: Archiv Oriental. vol. 69, Prag 2001, S. 363–418 (PDF; 31 MB).

- ^ Werner Kaiser: "The sun temples of the 5th Dynasty". In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute Cairo office. Vol 14, Mainz, 1956, p. 108

- ^ Cf. J.H. Breasted § 216-230, p. 100–106

- ^ cf. J. Ph. Lauer et A. Labrousse

- ^ Cf. J.H. Breasted § 156, p.68

- ^ Herbert Ricke. The sun temple of King Userkaf 2 vols; Cairo 1965-1969

- ^ Ian Shaw The Oxford history of ancient Egypt p.98-99

- ^ #ArchAb1

- ^ #ArchAb2

Bibliography

- Mariette, Auguste (1889). Les mastabas de l’Ancien Empire. Paris. AM.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ; - Sethe, Kurt Heinrich (1903). Urkunden des Alten Reich. Vol. 1. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs'sche Burchhandlung. KHS. ;

- Jean-Philippe Lauer & Audran Labrousse (2000). Les complexes funéraires d'Ouserkaf et de Néferhétepès. IFAO. LL..

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient records of Egypt historical documents from earliest times to the persian conquest, collected edited and translated with commentary. The University of Chicago press. JHB.

- Daressy, Georges (1916). La Pierre de Palerme et la chronologie de l'Ancien Empire. Cairo: BIFAO. GD.

- Hellouin de Cenival, Jean-Louis; Paule Posener-Krieger (1968). The Abusir Papyri, Series of Hieratic Texts. London: British Museum. ;

- Posener-Krieger, Paule (1976). Les Archives du temple funéraire de Néferirkarê-Kakai (Les Archives d'Abousir). IFAO. ;

Further reading

- Hawass, Zahi, "The Head of Userkaf" in "The Splendour of the Old Kingdom" in The Treasures of the Egyptian Museum, Francesco Tiradritti (editor), The American University in Cairo Press, 1999, p. 72-73.

- Magi, Giovanna. Saqqara: The Pyramid, The Mastabas and the Archaeological Site, Casa Editrice Bonechi, 2006

- Mahfouz, Naguib. "King Userkaf's Forgiveness" in Voices from the Other World (translated by Robert Stock), Random House, 2003.

- Verbrugghe, Gerald and Wickersham, John. Berossos and Manetho, University of Michigan Press 2001 (ISBN 0-472-08687-1)