Valley of the Fallen

The Valle de los Caídos (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbaʎe ðe los kaˈiðos], "Valley of the Fallen") is a Catholic basilica and a monumental memorial in the municipality of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, erected at Cuelgamuros Valley in the Sierra de Guadarrama, near Madrid, conceived by Spanish general Francisco Franco to honour and bury those who fell fighting for his "Glorious Crusade", during the Spanish Civil War.[1][2] It was[when?] claimed by Franco that the monument was meant to be a "national act of atonement" and reconciliation. The Valley of the Fallen, as a surviving monument of Franco's rule, and its Catholic basilica remain controversial, in part since 10% of the construction workforce consisted of convicts, some of whom were Spanish Republican political prisoners.

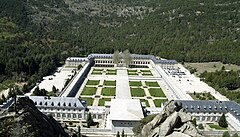

The monument, a landmark of 20th-century Spanish architecture, was designed by Pedro Muguruza and Diego Méndez on a scale to equal, according to Franco, "the grandeur of the monuments of old, which defy time and memory." Together with the Universidad Laboral de Gijón, it is the most prominent example of the original Spanish Neo-Herrerian style, which was intended to form part of a revival of Juan de Herrera's architecture, exemplified by the royal residence El Escorial. This uniquely Spanish architecture was widely used in public buildings of post-war Spain and is rooted in international classicism as exemplified by Albert Speer or Mussolini's Esposizione Universale Roma.

The monument precinct covers over 3,360 acres (13.6 km2) of Mediterranean woodlands and granite boulders on the Sierra de Guadarrama hills, more than 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level and includes a basilica, a Benedictine abbey, a guest house, the Valley, and the Juanelos — four cylindrical monoliths dating from the 16th century. The most prominent feature of the monument is the towering 150-metre-high (500 ft) cross erected over a granite outcrop 150 meters over the basilica esplanade and visible from over 20 miles (32 km) away.

Work started in 1940 and took over eighteen years to complete, the monument being officially inaugurated on April 1, 1959. According to the official ledger, the cost of the construction totalled 1,159 billion pesetas, funded through national lottery draws and donations.

The complex is owned and operated by the Patrimonio Nacional, the Spanish governmental heritage agency, and ranked as the third most visited monument of the Patrimonio Nacional in 2009. The Spanish social democrat government closed the complex to visitors at the end of 2009, citing safety reasons connected to restoration on the facade. The decision was controversial, as the closure was attributed by some people to the Historical Memory Law enacted during José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero's premiership,[3] and there were claims that the Benedictine community was being persecuted.[4] The works include the Pietà sculpture prominently featured at the entrance of the crypt, using hammers and heavy machinery.[5][6] In November 2010, citing safety reasons, the Zapatero government closed down the Basilica for Mass.[7] Mass was celebrated in the open for several weeks. Checkpoints were set up, according to socialist government sources, to prevent right-wing political manifestations such as Falange flags, in accordance with the Historical Memory Law. However, Catholic sources claimed that the government was simply trying to interfere with the celebration of the Mass. After Zapatero's electoral defeat and his leaving office on December 21, 2011, normal service at the Basilica resumed.

Basilica, cross and abbey

One of the world's largest basilicas rises above the valley along with the tallest memorial cross in the world. The Basílica de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos (Basilica of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen) is hewn out of a granite ridge. The 152.4-metre-high cross is constructed of stone and strongly resembles the ancient stone or granite open air outdoor crosses of Kerala known as Nazraney Sthambas.

In 1960, Pope John XXIII declared the underground crypt a basilica. The dimensions of this underground basilica, as excavated, are larger than those of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. To avoid competition with the apostle's grave church on the Vatican Hill, a partitioning wall was built near the inside of the entrance and a sizable entryway was left unconsecrated.

The monumental hieratic sculptures over the main gate and the base of the cross culminated the career of Juan de Ávalos. The monument consists of a wide explanada (esplanade) with a spectacular view of the valley and the outskirts of Madrid in the distance. A long vaulted crypt was tunnelled out of solid granite, piercing the mountain to the massive transept, which lies exactly below the cross.

On the wrought-iron gates, Franco's neo-Habsburg double-headed eagle is prominently displayed. On entering the basilica, visitors are flanked by two large metal statues of art deco angels holding swords.

There is a funicular that connects the basilica with the base of the cross. There is a spiral staircase and a lift inside the cross, connecting the top of the basilica dome to a trapdoor on top of the cross,[8] but their use is restricted to maintenance staff.

The Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen (Template:Lang-es), on the other side of the mountain, houses priests who say perpetual Masses for the repose of the fallen of the Spanish Civil War and later wars and peacekeeping missions fought by the Royal Spanish Army. The abbey ranks as a Royal Monastery.

Valley of the Fallen

The valley that contains the monument, preserved as a national park, is located 10 km northeast of the royal site of El Escorial, northwest of Madrid. Beneath the valley floor lie the remains of 40,000 people, whose names are accounted for in the monument's register. The valley contains both Nationalist and Republican graves.

Franco's tomb

In 1975, after Franco's death, the site was designated by the interim Government, assured by Prince Juan Carlos and Prime Minister Carlos Arias, as the burial place for Franco. According to his family, Franco did not want to be buried in the Valley, but in the city of Madrid. Nonetheless, the family agreed to the interim Government's request to bury him in the Valley, and has stood by the decision.

Before his death, nobody had expected that Franco would be buried in the Valley. Moreover, the grave had to be excavated and prepared within two days, forcing last minute changes in the plumbing system of the Basilica. Unlike the fallen of the Civil War who were laid to rest in the valley exterior to the basilica, Franco was buried inside the church. His grave is marked by a simple tombstone engraved with just his Christian name and first surname, on the choir side of the main high altar (between the altar and the apse of the Church; behind the altar, from the perspective of a person standing at the main door).

Franco is the only person interred in the Valley who did not die in the Civil War. The argument given by the defenders of his tomb is that in the Catholic Church the developer of a church can be buried in the church that he has promoted. Therefore, Franco would be in the Valley as the promoter of the basilica's construction.

Franco was the second person interred in the Santa Cruz basilica. Franco had earlier interred José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Falange movement, who was executed by the Republican government in 1936 and was laid to rest by the Francoist government under a modest gravestone on the nave side of the altar. Primo de Rivera died November 20, 1936, exactly 39 years before Franco, whose grave is in the corresponding position on the other side of the altar. Accordingly, 20 November is annually commemorated by large crowds of Franco supporters and various Falange successor movements and individuals, flocking to the Requiem Masses held for the repose of the souls of their political leaders.

Controversy

Presenting the monument in a politically neutral way poses a number of problems, not least the strength of opposing opinions on the issue. The Times quoted Jaume Bosch, a Catalan politician and former MP seeking to change the monument,[clarification needed] as saying: "I want what was in reality something like a Nazi concentration camp to stop being a nostalgic place of pilgrimage for Francoists. Inevitably, whether we like it or not, it's part of our history. We don’t want to pull it down, but the Government has agreed to study our plan."[9]

The charge that the monument site was "like a Nazi concentration camp" refers to the use of convicts, including Spanish Republican Army war prisoners, trading their labor for a reduction in time served. Although Spanish law at the time prohibited forced labor, it did provide for convicts to choose voluntary work on the basis of redeeming two days of conviction for each day worked. This law was in force until 1995. This benefit was increased to six days when labor was carried out at the basilica with a salary of 7 pesetas per day, a regular worker's salary for that time, with the possibility of the family of the convict benefiting from the housing and Catholic children schools built on the valley for the other workers. Only convicts with a record of good behaviour would qualify for this redemption scheme, as the works site was considered to be a low security environment. The motto used by the Spanish Nationalist government was "el trabajo enoblece" ("Work ennobles"). Some sources claim that by 1943, the number of prisoners who had worked at the site reached close to six hundred.[10] Other sources claim that up to 20,000 prisoners were used for the overall construction of the monument and that forced labor took place.[11]

According to the official program records, 2,643 workers participated directly in the construction, some of them highly skilled, as required by the complexity of the work. Only 243 of these were convicts. During the eighteen-year construction period, the official tally of workers who died as result of accidents during the building of the monument totalled fourteen.[12]

The socialist Spanish government of 2004-2011 instituted a state-wide policy of removal of Francoist symbols from public buildings and spaces, leading to an uneasy relationship with a monument that is the most conspicuous legacy from Franco's rule.

Political rallies in celebration of the former leader are now banned by the Historical Memory Law, voted on by the Congress of Deputies on 16 October 2007. This law dictated that "the management organisation of the Valley of the Fallen should aim to honor the memory of all of those who died during the civil war and who suffered repression".[13] It has been suggested that The Valley of the Fallen be re-designated as a "monument to Democracy" or as a memorial to all Spaniards killed in conflict "for Democracy".[14] Some organisations, among them centrist Catholic groups, question the purpose of these plans, on the basis that the monument is already dedicated to all of the dead, civilian and military of both Nationalist and Republican sides.

Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen

On November 29, 2011 the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen, formed by the Socialist Party government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero on May 27, 2011 under the Historical Memory Law and charged to give advice for converting the Valley of the Fallen to a "memory center that dignifies and rehabilitates the victims of the Civil War and the subsequent Franco regime,"[15] rendered a report[16] recommending as its principal proposal for the Commission's stated end the removal of the remains of Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen for reburial at a location to be chosen by his family, but only after first obtaining a broad parliamentary consensus for such action. The Commission based its decision upon Franco having not died in the Civil War and the aim of the Commission that the Valley of the Fallen be exclusively for those on both sides who had died in the Civil War. In regard to José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of Falange Española, the Commission recommended his remains should stay at the Valley of the Fallen, since a victim of the Civil War, but relocated within the Basilica mausoleum on equal footing with those remains of others who died in the conflict. The Commission further conditioned its recommendation for the removal of the remains of Franco from the Valley of the Fallen and the relocation of the remains of Primo de Rivera within the Basilica mausoleum upon the consent of the Catholic Church since “any action inside of the Basilica requires the permission of the Church.” Three members of the twelve person commission gave a joint dissenting opinion opposing the recommendation for the removal of the remains of Franco from the Valley of the Fallen claiming such action would only further “divide and stress Spanish society."[17] The Commission additionally proposed for its report creating a "meditation center" in the Valley of the Fallen for those not of the Catholic faith, the names shown of all Civil War victims buried at the Valley of the Fallen who can be identified on the esplanade that leads into the Basilica mausoleum and an “interpretive center” be built to explain how and why the Valley of the Fallen exists. The total cost of the proposed changes to the Valley of the Fallen was estimated by the Commission at 13 million euros.[18] On November 20, nine days before the issuance of the report of the Commission and ironically on the 36th anniversary of the death of Francisco Franco, the conservative Popular Party won for the 2011 General Election absolute majorities in both Spain’s lower house, the Congress of Deputies, and Senate.[19]

On July 17, 2012, Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría, Vice President and Spokesperson of the government stated during parliamentary questioning the Popular Party government of President Mariano Rajoy had no intention of following the recommendations of the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen with respect to the removal of the remains of Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen, the relocation of the remains of Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera within the Basilica or otherwise since the government considers the report to lack validity in that the Commission was “monocolor” for which the Popular Party was not invited or involved and that in light of Spain’s present economic crisis, discussion and opinion as to the Valley of the Fallen would not be considered at this time.[20][21][22]

On October 10, 2012 a motion of Basque Nationalist Party Senator Iñaki Anasagasti placed before the full Senate calling for the removal of the remains of Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen as recommended by the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen was rejected by the Popular Party majority. Together with the motion to remove the remains of Franco, the Popular Party majority also voted down an amendment by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party for the creation of a parliamentary committee to seek a consensus for the implementation of the recommendations of the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen. In a speech at the time before the Senate in defense of his party’s no votes Popular Party Senator Alejandro Muñoz-Alonso argued there is no consensus at present in Spain for implementing the recommendations of the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen and even the Expert Commission unilaterally formed by the Zapatero government was not unanimous, and the matter is now totally exhausted for having been raised eight times before the Parliament; and, then closed for his remarks by quoting from the bible saying, “let the dead bury the dead” for urging the Senate in light of Spain's economic crisis to return to addressing the "problems of the living."[23][24][25]

On July 8, 2013 a motion before the Senate of Catalan Agreement of Progress (ECP) to implement all recommendations made unanimously by the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen; that is, all recommendations with the exception only for the removal of the remains of Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen, was voted down by the Popular Party majority.[26]

On August 5, 2013 the Popular Party government by letter to Socialist Party deputy and former minister Ramon Jauregui reaffirmed its position that the recommendations of the Expert Commission for the Future of the Valley of the Fallen would not be carried out since doing so absent in the view of the Popular Party government a consensus in Spain for such action would "needlessly reopen old wounds." In regard to the expenditure of nearly 300,000 euros to restore the facade of the Basilica also questioned by former minister Jauregui, the Rajoy government further stated for its correspondence such expenditures are justified since aimed at ensuring the monument is well preserved and to prevent deterioration and possible risks to visitors.[27][28]

On November 4, 2013, Vice-President Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría again stated the Rajoy government will reject due to the lack of a consensus among Spaniards concerning the future of the Valley of the Fallen any legislation or request which would seek to remove the remains of Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen for reburial at a location to be chosen by his family and further questioned the urgency for that legislation then presently introduced before the Parliament calling for the removal of the remains of Franco since during the entire seven year term of the Zapatero government no attempt was made to so change the Valley of the Fallen.[29][30][31]

On November 23, 2014 the government of Mariano Rajoy again re-affirmed its position that since a social and political consensus is absent for doing so there can be no changes or modifications to the Valley of the Fallen.[32]

On December 17, 2014 Popular Party and Asturias Forum (FAC) members of the Committee for Culture of the Congress of Deputies together voted down a proposed law put forward by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party to “redefine” the Valley of the Fallen to reflect a “culture of co-existence,” and amendment of the United Left to exhume the remains of Francisco Franco and Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, identify the remains of all Civil War victims buried in the Basilica mausoleum,and address the claims of descendants whose ancestors were buried there without family consent. During parliamentary debate for the proposal of the PSOE, Popular Party deputy Rocio Lopez argued "let the dead rest in peace" and the Valley of the Fallen is a church and cemetery conceived as a peaceful place “without political significance” for the meeting and reconciliation of both sides of the Civil War that should not be changed or modified, while in support of the proposal PSEO deputy Odon Elorza contended the monument is instead a “symbol of contempt and exclusion” to Spaniards.[33][34]

Closure and reopening of the monument

In November 2009, Patrimonio Nacional controversially ordered the closure of the basilica for an indefinite period of time, alleging preservation issues also affecting the Cross and some sculptures.[3] These allegations were contested by experts and the Benedictine Order religious community that lives at the complex, and were seen by some conservative opinion groups as a policy of harassment against the monument.[35] In 2010, the Pietà sculpture group started to be "dismantled" with hammers and heavy machinery, which the Juan de Ávalos trust feared could cause irreparable damage to the masterpiece. As a result thereof, the trust filed several lawsuits against the Spanish government.[36] At the time, several parallelisms were made by conservative and liberal groups between the dismantling of the Pietà under the Socialist Party government of Zapatero and the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan by the Taliban.[37][38]

Following the November 2011 Spanish General Election, on June 1, 2012 the conservative Popular Party government of Mariano Rajoy reopened the monument to the public with the exception only of the base of the cross, in the past accessible by cable car or on foot, which will remain closed to ascent while the sculptures of the four apostles and the cardinal virtues forming part of the base of the cross are presently under engineering review and restoration for cracks and other deterioration.[39] Beginning on June 1, 2012 the charge for entry to the monument had been 5 euros. The 5 euro entry fee was anticipated to generate around 2 million euros a year if the Valley of the Fallen once again attracted 500,000 visitors annually, the approximate number of annual visitors before closure of the monument in 2009 by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero.[22][40] Starting on May 2, 2013, and over the strong objection of the Association for the Defense of the Valley of the Fallen, the entry fee for the monument was increased from 5 to 9 euros.[41][42][43] Prior to its closure in 2009, the Valley of the Fallen was the third most visited site of the Patrimonio Nacional after only the Royal Palace of Madrid and El Escorial.[44] For the accommodation of visitors a cafeteria restaurant located in the cable car building of the monument has been opened.[45]

In popular culture

The Valle de los Caídos appears in Richard Morgan's 2002 novel Altered Carbon, where it is being used as a base of operations for one of the major antagonists, Reileen Kawahara.[46] It also appears in the 2010 Spanish comedy terror film The Last Circus (Spanish: Balada triste de trompeta). Graham Greene's 1982 novel Monsignor Quixote uses a visit to the Valle to illustrate the competing political and social attitudes to Franco's reign and the status of his tomb in modern Spain. In Carlos Saura's Deprisa, Deprisa, a youth gang visits the Valle and makes fun of its pretentiousness, to the shock of pious visitors.

There is also a large reference to this monument and the laborers who built it in Victoria Hislop's book The Return. A number of rock crosses, free-standing outdoor stone crosses are to be found in Kerala churches of southern India, many of them from pre-Portuguese times that look exactly like the Valle de los Caídos rock cross but much smaller, of a height of 15–35 ft. But it is possible that these free standing pillars or Nazraney Sthambas employing the socket and cylinder technique to fit the shaft to the base piece and the arms to the shaft and finally the capital to the arms, altogether a four-piece work of precise architecture may have influenced the Spanish missionaries and scholars.[47]

In 2013 has been released in Spain the film All'Ombra Della Croce (A la Sombra de la Cruz)[48] directed by the Italian filmmaker Alessandro Pugno.[49] The film tells the secret story of the children of the chorus who sing every day in the mass.[50] They live in a boarding school inside the monument and receive an education that tries to resist the drift towards secularism and scientism of contemporary Spain and of global society.[51] The film has been awarded with the first prize for the best documentary at Festival de Málaga de Cine Español.

In 2016, Manuela Carmena proposed a change in the name "El valle de los caídos", to change it into "El valle de la paz"

See also

- Anıtkabir, Mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (Turkey)

- Mazar-e-Quaid (Pakistan)

- Che Guevara Mausoleum (Cuba)

- Cementerio de Santa Ifigenia (Cuba)

- Museo Histórico Militar de Caracas (Venezuela)

- Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum (Ghana)

- Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum (China)

- Cihu Mausoleum, Chiang Kai-shek (Republic of China, Taiwan)

- Touliao Mausoleum, Chiang Ching-kuo (Republic of China, Taiwan)

- Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum (Vietnam)

- House of Flowers (mausoleum), Josip Broz Tito (Serbia)

- Lenin's Mausoleum (Russia)

- Les Invalides, Sarcophagus of Napoleon Bonaparte (France)

- Mausoleum of Mao Zedong (China)

- Kumsusan Palace of the Sun (North Korea)

- National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (Republic of China, Taiwan)

- Türkmenbaşy Ruhy Mosque (Turkmenistan)

- Bourguiba's mausoleum in Monastir (Tunisia)

- Julius Nyerere's mausoleum in Butiama Cemetery (Tanzania)

- Jomo Kenyatta Mausoleum (Kenya)

- Arafat mausoleum (Palestinian)

- Abdel Nasser Mosque (Egypt)

- Unknown Soldier Memorial (Egypt) (Egypt)

- Mausoleum of Assad in Qardaha (Syria)

- Mausoleum of Khomeini (Iran)

- Marcos Museum and Mausoleum (Philippines)

- Astana Giribangun (Indonesia)

- Cimitero di San Cassiano (Italy)

References

- ^ "Fate of Franco's Valley of Fallen reopens Spain wounds". BBC. 2011.

- ^ "Decreto de 1 de abril de 1940 disponiendo se alcen Basílica, Monasterio y Cuartel de Juventudes, en la finca situada en las vertientes de la Sierra del Guadarrama (El Escorial), conocida por Cuelga-muros, para perpetuar la memoria de los caídos en nuestra Glroriosa Cruzada" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado n. 93 2 April 1940 (in Spanish): 2240.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Una Decision que Traera Polemica Ordenan el Cierre del Valle de los Caidos por Tiempo Indefinido" [A controversial decision: The indefinite closure of the Valley of the Fallen is ordered] (in Spanish). Diario de la Sierra. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|editorial=and|cite=(help) - ^ Juan Diego Quesada (15 November 2010). "El prior del Valle de los Caídos: "Nos persiguen como en 1934"" [The Prior of the Valley of the Fallen: "We are being persecuted like in 1934"] (in Spanish). El Pais. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "El desmontaje de 'La Piedad' del Valle de los Caídos, a 'mazazo limpio'". El Mundo (in Spanish). 23 April 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|cite=and|editorial=(help) - ^ "Images that show how the sculpture is being destroyed". Association for the Protection of the Valley of the Fallen.

- ^ "Valley of the Fallen: closed by government order" (in Spanish). Libertad Digital. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "The Monumental Cross" (in Spanish). Team VKi2. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Spain reclaims Franco's shrine". Times Online (subscription only). Retrieved 2014-07-29.

- ^ Cesar Vidal (22 October 2000). "How the Cross of the Fallen was constructed" (in Spanish). Libertad Digital. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Unknown Title". European Jewish Press. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Virginia Ródenas (15 September 2008). "La Fundación Francisco Franco no convocará más funerales el 20-N en el Valle de los Caídos" (in Spanish). ABC. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Official Bulletin of the Cortes Generales (report about the resolution voted at the Congress of Deputies" (PDF) (in Spanish). Congreso de los Diputados). 16 October 2007.

- ^ "Unknown Title". Times Online (subscription only).

- ^ "Expert Commission on the Future of the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). Memoria Histórica. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Expert Commission on the Future of the Valley of the Fallen" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministro de la Presidencia. 29 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Valley of the Fallen Commission proposes that Franco's remains are moved" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 29 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Valley of the Fallen Commission recommends that Franco's remains are moved" (in Spanish). ABC. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Spanish General Election Results". News from Spain. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Franco Seguirá En El Valle De Los Caídos" (in Spanish). Iñaki Anasagasti. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Los restos de Franco y de José Antonio no se mueven del Valle de los Caídos" (in Spanish). El Confidencial Digital. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ a b "El Gobierno acelera el pleno funcionamiento del Valle de los Caídos desde el día 1" (in Spanish). elConfidencial.com. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "El PP rechaza convertir el Valle de los Caídos en un "centro para la Memoria"" (in Spanish). ABC. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "El PP rechaza poner en marcha la reforma del Valle de los Caídos y considera el asunto "totalmente agotado"" (in Spanish). Telecinco.es. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Mayoria PP rechaza una mocion para trasladar los restos franco". Intereconomia. 10 October 2012. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The PP wants the Valley of the Fallen is left as is" (in Spanish). El Diario. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Government announces that Franco's remains will remain in the Valley of the Fallen so as not to 'needlessly reopen old wounds'" (in Spanish). Kaos en la Red. 6 August 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Government believes that changing the Valley of the Fallen would 'needlessly reopen old wounds'" (in Spanish). Cadena Ser. 29 October 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Vice President refuses to remove Franco from the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Periodico. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Sáenz de Santamaría cites the lack of consensus on the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). Europasur. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Vice President refuses to remove Franco from the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Periodico Extremadura. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "El Valle de los Caídos sólo se modificará si hay "consenso político y social"" [The Valley of the Fallen can only be modified if there is "political and social consensus"] (in Spanish). ABC. 24 November 2014.

- ^ l.l.c. / madrid (2014-12-18). "El intento del PSOE por "resignificar" el Valle de los Caídos "rezuma odio", según el PP". ABC.es. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ "El PP proclama que el Valle de los Caídos no tiene "significación política" y pide dejar descansar a los muertos" (in Spanish). Europapress.es. 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ Pío Moa (14 February 2010). "The Valley of the Fallen and the Taliban" (in Spanish). Libertad Digital. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Juan de Avalos's son complains to National Heritage about the dismantling of the Pietà" (in Spanish). Libertad Digital. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The controversial removal of 'La Pieta' Valley of the Fallen begins" (in Spanish). Público. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Taliban Socialists decapitate Avalos' Pietá in the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). Aragon Liberal. 6 November 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "National Heritage calls for a report about the restoration of the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The state will earn two million Euros by charging for entry to the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Mundo. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Patrimonio Nacional sube un 80 entradas Valle de Los caidos" (in Spanish). Intereconomia. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The PP government wants to close the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). El Confidencial Digital. 26 April 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The Association for the Protection of the Valley of the Fallen is collecting signatures against rising prices at the Monument" (in Spanish). Europa Press. 4 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "National Heritage calls for a report on the restoration of the Valley of the Fallen" (in Spanish). La Informacion. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Cafetería Del Funicular Del Valle De Los Caídos" (in Spanish). Asociación Para La Defensa Del Valle De Los Caídos. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Morgan, Ricahard K. (2002). Altered Carbon. Del Rey Book. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-345-45768-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Menachery, George (1973). St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "All'Ombra Della Croce (In the Shadow of the Cross) (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Franco's choirboys" (in Spanish). El Pais. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "The school that Franco built". Deutsche Welle. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Synopsis All'ombra della croce" (in Spanish). Punto de Vista. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

External links

- WAIS Forum on Spain, 2003: "Spain: the Valley of the Fallen": includes quote from Franco's decree, April 1, 1940

- Abadía de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos: Official Website Template:Es icon.

- El Valle de los Caidos: Template:Es icon

- Fundacion Francisco Franco, Valle de los Caidos: from Franco's Memorial Trust Template:Es icon

- Valley of the Fallen: visitor information and photos

- Cruz de los Caídos drawings and plans from the architectural website skyscraperpage.com

- The Valley of the Fallen: History and Photos.

- "Manifesto for historians regarding the Valley of the Fallen" by Pio Moa, leading Spanish historian about the construction of the monument and the alleged government policy of harassment Template:Es icon