Virtual reality headset

This article needs to be updated. (June 2016) |

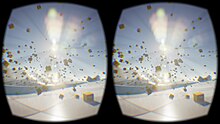

A virtual reality headset is a head-mounted device aimed to provide an immersive virtual reality experience, for the purpose of computer games and 3D simulations. It consists of a stereoscopic head-mounted display (providing separate images for each eye) and head motion tracking sensors[1] (which may include gyroscopes, accelerometers, structured light systems,[2] etc.). Some devices also include headphones, eye tracking sensors[3] and gaming controllers.

History

One of the first commercially available headsets was the Forte VFX1 which was announced at CES in 1994. The VFX-1 had stereoscopic displays, 3-axis head-tracking, and stereo headphones.[4] Another pioneer in this field was Sony who released the Glasstron in 1997, which had an optional positional sensor which permitted the user to view the surroundings, with the perspective moving as the head moved, providing a deep sense of immersion. One novel application of this technology was in the game MechWarrior 2, which permitted users of the Sony Glasstron or Virtual I/O's iGlasses to adopt a new visual perspective from inside the cockpit of the craft, using their own eyes as visual and seeing the battlefield through their craft's own cockpit.

However, these early headsets were unsuccessful in the marketplace due to primitive technology,[5][6] described by John Carmack as "looking through toilet paper tubes".[7] A new era in VR headsets started around 2012, when the plans for Oculus Rift were announced with a Kickstarter campaign, attracting industry attention from several prominent video game developers, including John Carmack[5] who later became the company's CTO.[8] Since then, multiple development kits and prototypes were released,[6] with the final product being planned for release on 28 March 2016.[9]

In the meanwhile, multiple competitors appeared to Oculus. In March 2014, Sony demonstrated a prototype headset for PlayStation 4,[10] which was later named PlayStation VR.[11] In 2014, Valve Corporation demonstrated some headset prototypes,[12] which later turned into a partnership with HTC to produce the HTC Vive headset.[13] The Vive is now planned for a release in April 2016[14] and PlayStation VR later in 2016.[15]

Another breed of new VR headsets coming up are devices that pair with a mobile phone to use the phone's display or processing power to drive the headset. Examples of this range from the rudimentary Google Cardboard to the fairly sophisticated Samsung Gear VR and LG 360 VR. The Samsung Gear VR is currently available for sale as well as being included in bundle offers with Samsung smartphones.[16] This headset uses both the display and processing power of the paired Samsung phone. The LG 360 VR on the other hand uses just the processing power of the phone and has its own built in displays.[17]

Constraints

Latency requirements

Virtual reality headsets have significantly higher requirements for latency—the time it takes from a change in input to have a visual effect—than ordinary video games.[18] If the system is too sluggish to react to head movement, then it can cause the user to experience virtual reality sickness, a kind of motion sickness.[19] According to a Valve engineer, the ideal latency would be 7-15 milliseconds.[20] A major component of this latency is the refresh rate of the display,[19] which has driven the adoption of displays with a refresh rate from 90 Hz (Oculus Rift and HTC Vive) to 120 Hz (PlayStation VR).[15]

The graphics processing unit (GPU) also needs to be more powerful to render frames more frequently. Oculus cited the limited processing power of Xbox One and PlayStation 4 as the reason why they are targeting the PC gaming market with their first devices.[21]

Asynchronous reprojection/time warp

A common way to reduce the perceived latency[22] or compensate for a lower frame rate,[23] is to take an (older) rendered frame and morph it according to the most recent head tracking data just before presenting the image on the screens. This is called asynchronous reprojection[24] or "asynchronous time warp" in Oculus jargon.[25]

PlayStation VR synthesizes "in-between frames" in such manner, so games that render at 60 fps natively result in 120 updates per second.[15][23] SteamVR (HTC Vive) will also use "interleaved reprojection" for games that cannot keep up with its 90 Hz refresh rate, dropping down to 45 fps.[26]

The simplest technique is applying only projective transformation to the images for each eye (simulating rotation of the eye). The downsides are that this approach cannot take into account the translation (changes in position) of the head. And the rotation can only happen around the axis of the eyeball, instead of the neck, which is the true axis for head rotation. When applied multiple times to a single frame, this causes "positional judder", because position is not updated with every frame.[22][27][28]

A more complex technique is positional time warp, which uses pixel depth information from the Z-buffer to morph the scene into a different perspective. This produces other artifacts because it has no information about faces that are hidden due to occlusion[27] and cannot compensate for position-dependent effects like reflections and specular lighting. While it gets rid of the positional judder, judder still presents itself in animations, as timewarped frames are effectively frozen.[28] Support for positional time warp was added to the Oculus SDK in May 2015.[29]

Resolution and display quality

Because virtual reality headsets stretch a single display across a wide field of view (up to 110° for some devices according to manufacturers), the magnification factor makes flaws in display technology much more apparent. One issue is the so-called screen-door effect, where the gaps between rows and columns of pixels become visible, kind of like looking through a screen door.[30] This was especially noticeable in earlier prototypes and development kits,[6] which had lower resolutions than the retail versions.

Lenses

The lenses of the headset are responsible for mapping the up-close display to a wide field of view,[31][32] while also providing a more comfortable distant point of focus. One challenge with this is providing consistency of focus: because eyes are free to turn within the headset, it's important to avoid having to refocus to prevent eye strain.[33]

The lens introduce distortion and chromatic aberration, which are corrected in software.[31]

Uses in various fields

Medicine

Medical training

Virtual reality headsets are being currently used as means to train medical students for surgery. It allows them to perform essential procedures in a virtual, controlled environment. Students perform surgeries on virtual patients, which allows them to acquire the skills needed to perform surgeries on real patients.[34] It also allows the students to revisit the surgeries from the perspective of the lead surgeon.[35]

Traditionally, students had to participate in surgeries and often they would miss essential parts. But, now surgeons have been recording surgical procedures and students are now able to watch whole surgeries again from the perspective of lead surgeons with the use of VR headsets, without missing essential parts. Students can also pause, rewind, and fast forward surgeries.[35]

See also

References

- ^ Ben Kuchera (15 January 2016). "The complete guide to virtual reality in 2016 (so far)". Polygon.

- ^ Adi Robertson. "The ultimate VR headset buyer's guide". TheVerge.com. Vox Media.

- ^ Stuart Miles (19 May 2015). "Forget head tracking on Oculus Rift, Fove VR headset can track your eyes". Pocket-lint.

- ^ Nathan Cochrane (1994). "VFX-1 VIRTUAL REALITY HELMET by Forte". Game Bytes Magazine.

- ^ a b "Oculus Rift virtual reality headset gets Kickstarter cash". BBC News. 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Greg Kumparak (26 March 2014). "A Brief History Of Oculus". TechCrunch.

- ^ Charles Onyett (3 August 2012). "The Future of Gaming in Virtual Reality". IGN.

- ^ Alex Wilhelm (22 November 2013). "Doom's John Carmack Leaves id Software To Focus On The Oculus Virtual Reality Headset". TechCrunch.

- ^ Steve Dent (6 January 2016). "The Oculus Rift costs $599 and ships in March". Engadget.

- ^ Michael McWhertor (18 March 2014). "Sony announces Project Morpheus, a virtual reality headset coming to PlayStation 4". Polygon.

- ^ Aaron Souppouris (15 September 2015). "Sony's Project Morpheus is now 'PlayStation VR'". Engadget.

- ^ Tom Warren (3 June 2014). "Valve's VR headset revealed with Oculus-like features". The Verge.

- ^ "Valve's VR headset is called the Vive and it's made by HTC". The Verge. 1 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Adi Robertson (8 December 2015). "HTC Vive VR headset delayed until April". The Verge.

- ^ a b c Leo Kelion (4 March 2015). "Sony's Morpheus virtual reality helmet set for 2016 launch". BBC News.

- ^ Varghese, Jobin B. "Free Gear VR in India with Galaxy S7 & Galaxy S7 Edge". VRslashAR. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Varghese, Jobin B. "LG 360 VR - An Objective Analysis". VRslashAR. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Ben Lang (24 February 2013). "John Carmack Talks Virtual Reality Latency Mitigation Strategies". Road to VR.

- ^ a b "Virtual reality developers struggle with motion sickness". news.com.au. 21 March 2016.

- ^ Kyle Orland (4 January 2013). "How fast does "virtual reality" have to be to look like "actual reality"?". Ars Technica.

- ^ Eddie Makuch (13 November 2013). "Xbox One, PS4 "too limited" for Oculus Rift, says creator". GameSpot.

- ^ a b Matt Porter (28 March 2016). "Why the 'asynchronous timewarp' added to Oculus Rift matters". PC Gamer.

- ^ a b Jamie Feltham (15 March 2016). "PlayStation VR Price and Release Date Revealed". VRFocus.

- ^ S, Jon (19 March 2016). "The Tech Behind PlayStation VR And How It Delivers 120 Hz On Console". Game-Debate. Game-Debate.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Niel Schneider (12 October 2015). "Virtual Reality Basics". Tom's Hardware.

- ^ Aaron Leiby (26 March 2016). "Interleaved Reprojection now enabled for all applications by default". SteamVR Developer Hardware forums.

- ^ a b Andre Infante (21 April 2015). "Can Virtual Reality Cut the Cord?". MakeUseOf.

- ^ a b Michael Antonov (3 March 2015). "Asynchronous Timewarp Examined". Oculus developer blog.

- ^ Scott Hayden (19 May 2015). "Visualizing the Latest Features Found in Oculus SDK v0.6.0.0". Road to VR.

- ^ "Screen-Door Effect: PlayStationVR Supposedly Has "None", Probably Doesn't Matter". Talk Amongst Yourselves (Kinja). 27 March 2016.

- ^ a b Paul James (21 October 2013). "Intel Claims It Can Improve Image Quality for HMDs — Daniel Pohl Tells Us How". Road to VR.

- ^ Ben Lang (13 May 2015). "Wearality's 150 Degree Lenses Are a Balancing Act, Not a Breakthrough". Road to VR.

- ^ Matthew Terndrup (6 October 2015). "Palmer Luckey talks advantages of the Rift's custom lenses". UploadVR.

- ^ "Advantages of virtual reality in medicine - Virtual Reality". Virtual Reality. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ a b Rousseau, Rémi (13 August 2014). "Virtual surgery gets real: What the Oculus Rift could mean for the future of medicine". Medium. Retrieved 12 April 2016.