Washington Monument

| Washington Monument | |

|---|---|

(January 2006) | |

| Location | National Mall, Washington, D.C., United States |

| Area | 106.01 acres (42.90 ha) |

| Visitors | 671,031 (in 2008) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Official name | Washington Monument |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000035 |

The Washington Monument is an obelisk on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, once commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and the first American president. Standing almost due east of the Reflecting Pool and the Lincoln Memorial,[2] the monument, made of marble, granite, and bluestone gneiss,[3] is both the world's tallest stone structure and the world's tallest obelisk, standing 554 feet 7+11⁄32 inches (169.046 m) tall.[n 1] It is the tallest monumental column in the world if all are measured above their pedestrian entrances, but two are taller when measured above ground, though they are neither all stone nor true obelisks.[n 2]

Construction of the monument began in 1848, and was halted from 1854 to 1877 due to a lack of funds, a struggle for control over the Washington National Monument Society, and the intervention of the American Civil War. Although the stone structure was completed in 1884, internal ironwork, the knoll, and other finishing touches were not completed until 1888. A difference in shading of the marble, visible approximately 150 feet (46 m) or 27% up, shows where construction was halted and later resumed with marble from a different source. The original design was by Robert Mills, but he suspended his colonnade, proceeding only with his obelisk, whose flat top was altered to a pointed marble pyramidion in 1884. The cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1848; the first stone was laid atop the unfinished stump on August 7, 1880; the capstone was set on December 6, 1884; and the completed monument was dedicated on February 21, 1885.[13] It officially opened October 9, 1888. Upon completion, it became the world's tallest structure, a title previously held by the Cologne Cathedral. The monument held this designation until 1889, when the Eiffel Tower was completed in Paris, France.

The monument was damaged during the 2011 Virginia earthquake and Hurricane Irene in the same year and remained closed to the public while the structure was assessed and repaired.[14] After 32 months of repairs, the National Park Service and the Trust for the National Mall reopened the Washington Monument to visitors on May 12, 2014.[15][16][17][18][19]

History

Rationale

George Washington (1732–99), hailed as the father of his country, and as the leader who was "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen" (in eulogy by Maj. Gen. 'Light-Horse Harry' Lee at Washington's funeral, December 26, 1799), was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. Even his erstwhile enemy King George III called him "the greatest character of the age."[20]

At his death in 1799 he left a critical legacy; he exemplified the core ideals of the American Revolution and the new nation: republican virtue and devotion to civic duty. Washington was the unchallenged public icon of American military and civic patriotism. He was also identified with the Federalist Party, which lost control of the national government in 1800 to the Jeffersonian Republicans, who were reluctant to celebrate the hero of the opposition party.[21]

Proposals for a memorial

Starting with victory in the Revolution, there were many proposals to build a monument to Washington. After his death, Congress authorized a suitable memorial in the national capital, but the decision was reversed when the Democratic-Republican Party (Jeffersonian Republicans) took control of Congress in 1801.[22] The Republicans were dismayed that Washington had become the symbol of the Federalist Party; furthermore the values of Republicanism seemed hostile to the idea of building monuments to powerful men. They also blocked his image on coins or the celebration of his birthday. Further political squabbling, along with the North-South division on the Civil War, blocked the completion of the Washington Monument until the late 19th century. By that time, Washington had the image of a national hero who could be celebrated by both North and South, and memorials to him were no longer controversial.[23]

As early as 1783, the Continental Congress had resolved "That an equestrian statue of George Washington be erected at the place where the residence of Congress shall be established." The proposal called for engraving on the statue which explained it had been erected "in honor of George Washington, the illustrious Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States of America during the war which vindicated and secured their liberty, sovereignty, and independence."[24] Currently, there are two equestrian statues of President Washington in Washington, D.C. One is located in Washington Circle at the intersection of the Foggy Bottom and West End neighborhoods at the north end of the George Washington University, and the other is in the gardens of the National Cathedral.

Ten days after Washington's death, a Congressional committee recommended a different type of monument. John Marshall, a Representative from Virginia (who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) proposed that a tomb be erected within the Capitol. However, a lack of funds, disagreement over what type of memorial would best honor the country's first president, and the Washington family's reluctance to move his body prevented progress on any project.[25]

Design

Progress toward a memorial finally began in 1832. That year, which marked the 100th anniversary of Washington's birth, a large group of concerned citizens formed the Washington National Monument Society. In 1836, after they had raised $28,000 in donations ($Error when using {{Inflation}}: |index=US-NGDPPC (parameter 1) not a recognized index. in Error: undefined index "US-NGDPPC" when using {{Inflation/year}}.[[[Category:Pages with errors in inflation template]] 1]), they announced a competition for the design of the memorial.[26]: chp 1

On September 23, 1835, the board of managers of the society described their expectations:[27]

It is proposed that the contemplated monument shall be like him in whose honor it is to be constructed, unparalleled in the world, and commensurate with the gratitude, liberality, and patriotism of the people by whom it is to be erected ... [It] should blend stupendousness with elegance, and be of such magnitude and beauty as to be an object of pride to the American people, and of admiration to all who see it. Its material is intended to be wholly American, and to be of marble and granite brought from each state, that each state may participate in the glory of contributing material as well as in funds to its construction.

The society held a competition for designs in 1836. The winner was architect Robert Mills. The citizens of Baltimore had chosen him to build a monument to Washington, and he had designed a tall Greek column surmounted by a statue of the President. Mills also knew the capital well, having just been chosen Architect of Public Buildings for Washington. His design called for a tall obelisk—an upright, four-sided pillar that tapers as it rises—with a nearly flat top. He surrounded the obelisk with a circular colonnade, the top of which would feature Washington standing in a chariot. Inside the colonnade would be statues of 30 prominent Revolutionary War heroes.[28]

One part of Mills' elaborate design that was built was the doorway surmounted by an Egyptian-style Winged sun. It was removed in 1885, after the monument was dedicated. A photo can be seen in The Egyptian Revival by Richard G. Carrot.[29]

Criticism of Mills' design and its estimated price tag of more than $1 million ($Error when using {{Inflation}}: |index=US-NGDPPC (parameter 1) not a recognized index. in Error: undefined index "US-NGDPPC" when using {{Inflation/year}}.[[[Category:Pages with errors in inflation template]] 1])[30] caused the society to hesitate. Its members decided to start building the obelisk, and to leave the question of the colonnade for later. They believed that if they used the $87,000 they had already collected to start work, the appearance of the monument would spur further donations that would allow them to complete the project.[31]: 15

Construction

The Washington Monument was originally intended to be located at the point at which a line running directly south from the center of the White House crossed a line running directly west from the center of the Capitol. Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's 1791 "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States ..." designated this point as the location of the equestrian statue of George Washington that the Continental Congress had voted for in 1783.[32][n 3] The ground at the intended location proved to be too unstable to support a structure as heavy as the planned obelisk. At that originally intended site, which is 390 feet (119 m) WNW from the current monument, there now stands a small monolith called the Jefferson Pier.[36][37]

Excavation and initial construction

In early 1848, workers started to build the Washington Monument's foundation.[38] On July 4, 1848, the Freemasons, an organization to which Washington belonged, laid the cornerstone (symbolically, not physically).[39]: 45, 136–143 According to Joseph R. Chandler:[39]: 136, 140–141 [40]

No more Washingtons shall come in our time ... But his virtues are stamped on the heart of mankind. He who is great in the battlefield looks upward to the generalship of Washington. He who grows wise in counsel feels that he is imitating Washington. He who can resign power against the wishes of a people, has in his eye the bright example of Washington.[40]

Two years later, on a torrid July 4, 1850, George Washington Parke Custis, the adopted son of George Washington and grandson of Martha Washington, dedicated a stone from the people of the District of Columbia to the Monument at a ceremony that President Zachary Taylor attended five days before he died from food poisoning.[41]

Donations run out

Construction continued until 1854, when donations ran out and the monument had reached a height of 152 feet (46.3 m). At that time a memorial stone that was contributed by Pope Pius IX, called the Pope's Stone, was destroyed by members of the anti-Catholic, nativist American Party, better known as the "Know-Nothings", during the early morning hours of March 6, 1854 (a priest replaced it in 1982). This caused public contributions to the Washington National Monument Society to cease, so they appealed to Congress for money.[31]: 25–26 [42]: 16, 215, 222–3

The request had just reached the floor of the House of Representatives when the Know-Nothing Party seized control of the Society on February 22, 1855. Congress immediately tabled its expected contribution of $200,000 to the Society, effectively halting the appropriation. During its tenure, the Know-Nothing Society added only two courses of masonry, or four feet, to the monument using rejected masonry it found on site, increasing the height of the shaft to 156 feet. The original Society refused to recognize the illegal takeover, so two Societies existed side by side until 1858. With the Know-Nothing Party disintegrating and its inability to secure contributions toward building the monument, it surrendered its possession of the monument to the original Society on October 20, 1858. To prevent future takeovers, Congress incorporated the Society on February 22, 1859.[26]: chp 3 [39]: 52–65

Post–Civil War

Interest in the monument grew after the Civil War. Engineers studied the foundation several times to determine if it was strong enough. In 1876, the Centennial of the Declaration of Independence, Congress agreed to appropriate another $200,000 to resume construction.[38]

Before work could begin again, arguments about the most appropriate design resumed. Many people thought a simple obelisk, one without the colonnade, would be too bare. Architect Mills was reputed to have said omitting the colonnade would make the monument look like "a stalk of asparagus"; another critic said it offered "little ... to be proud of."[25]

This attitude led people to submit alternative designs. Both the Washington National Monument Society and Congress held discussions about how the monument should be finished. The society considered five new designs, concluding that the one by William Wetmore Story seemed "vastly superior in artistic taste and beauty." Congress deliberated over those five as well as Mills' original. While it was deciding, it ordered work on the obelisk to continue. Finally, the members of the society agreed to abandon the colonnade and alter the obelisk so it conformed to classical Egyptian proportions.[27]

Resumption

Construction resumed in 1879 under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Casey redesigned the foundation, strengthening it so it could support a structure that ultimately weighed more than 40,000 tons. He then followed the society's orders and figured out what to do with the memorial stones that had accumulated. Though many people ridiculed them, Casey managed to install most of the stones in the interior walls — one stone was found at the bottom of the elevator shaft in 1951.[42] The bottom third of the monument is a slightly lighter shade than the rest of the construction because the marble was obtained from different quarries.[43]

The building of the monument proceeded quickly after Congress had provided sufficient funding. In four years, it was completed, with the 100-ounce (2.83 kg) aluminum apex/lightning-rod being put in place on December 6, 1884.[38] The apex was the largest single piece of aluminum cast at the time, when aluminum commanded a price comparable to silver.[10] Two years later, the Hall–Héroult process made aluminum easier to produce and the price of aluminum plummeted, making the once-valuable apex more ordinary, though it still provided a lustrous, non-rusting apex that served as the original lightning rod.[44] The monument opened to the public on October 9, 1888.[45]

Dedication

The Monument was dedicated on February 21, 1885.[13] Over 800 people were present on the monument grounds to hear speeches during a frigid day by Ohio Senator John Sherman, the Rev. Henderson Suter, William Wilson Corcoran (of the Washington National Monument Society) read by Dr. James C. Welling because Corcoran was unable to attend, Freemason Myron M. Parker, Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey of the Army Corps of Engineers, and President Chester A. Arthur.[38][46] President Arthur proclaimed:

I do so now .... in behalf of the people, receive this monument .... and declare it dedicated from this time forth to the immortal name and memory of George Washington.[46]

After the speeches Lieutenant-General Philip Sheridan led a procession, which included the dignitaries and the crowd, past the Executive Mansion, now the White House, then via Pennsylvania Avenue to the east main entrance of the Capitol, where President Arthur received passing troops. Then, in the House Chamber, the president, his Cabinet, diplomats and others listened to Representative John Davis Long read a speech written a few months earlier by Robert C. Winthrop, formerly the Speaker of the House of Representatives when the cornerstone was laid 37 years earlier, but now too ill to personally deliver his speech.[39]: 234–260 A final speech was given by John W. Daniel of Virginia. The festivities concluded that evening with fireworks, both aerial and ground displays.[39]: 260–285 [47][48]

Later history

At the time of its completion, it was the tallest building in the world, a title it retained until the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889; however, the Washington Monument is still the tallest stone structure in the world.[49][n 2] It is the tallest building in Washington, D.C.[50][51] The Heights of Buildings Act of 1910 restricts new building heights to no more than 20 feet (6.1 m) greater than the width of the adjacent street.[52] This monument is vastly taller than the obelisks around the capitals of Europe and in Egypt and Ethiopia, but ordinary antique obelisks were quarried as a monolithic block of stone, and were therefore seldom taller than approximately 100 feet (30 m).[53]

The Washington Monument attracted enormous crowds before it officially opened. For six months after its dedication, 10,041 people climbed the 898 steps and 50 landings to the top. After the elevator that had been used to raise building materials was altered to carry passengers, the number of visitors grew rapidly, and an average of 55,000 people per month were going to the top by 1888.[54] The annual visitor count peaked between 1979–97, where an average of 1.1 million visitors visited annually; however, from 2005–10, the Washington Monument has had an average of only 631,000 visitors each year.[55] As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, the national memorial was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[56]

In the early 1900s, material started oozing out between the outer stones of the first construction period below the 150-foot mark, and was referred to by tourists as "geological tuberculosis". This was caused by the weathering of the cement and rubble filler between the outer and inner walls. As the lower section of the monument was exposed to cold and hot and damp and dry weather conditions, the material dissolved and worked its way through the cracks between the stones of the outer wall, solidifying as it dripped down their outer surface.[57]

For ten hours in December 1982, the Washington Monument and eight tourists were held hostage by a nuclear arms protester, Norman Mayer, claiming to have explosives in a van he drove to the monument's base. U.S. Park Police shot and killed Mayer. The monument was undamaged in the incident, and it was discovered later that Mayer did not have explosives. After this incident, the surrounding grounds were modified in places to restrict the possible unauthorized approach of motor vehicles.[58]

The monument underwent an extensive restoration project between 1998 and 2001. During this time it was completely covered in scaffolding designed by the American architect Michael Graves (who was also responsible for the interior changes).[59] The project included cleaning, repairing and repointing the monument's exterior and interior stonework. The stone in publicly accessible interior spaces was encased in glass to prevent vandalism, while new windows with narrower frames were installed (to increase the viewing space). New exhibits celebrating the life of George Washington, and the monument's place in history, were also added.[60]

A temporary interactive visitors center, dubbed the "Discovery Channel Center" was also constructed during the project. The center provided a simulated ride to the top of the monument, and shared information with visitors during phases in which the monument was closed.[61] The majority of the project's phases were completed by summer 2000, allowing the monument to reopen July 31, 2000.[60] The monument temporarily closed again on December 4, 2000 to allow a new elevator cab to be installed, completing the final phase of the restoration project. The new cab included glass windows, allowing visitors to see some of the 194 memorial stones embedded in the monument's walls. The installation of the cab took much longer than anticipated, and the monument did not reopen until February 22, 2002. The final cost of the restoration project was $10.5 million.[62]

On September 7, 2004 the monument closed for a $15 million renovation, which included numerous security upgrades and redesign of the monument grounds by landscape architect Laurie Olin. The renovations were due partly to security concerns following the September 11 attacks and the start of the War on Terror. The monument reopened April 1, 2005, while the surrounding grounds remained closed until the landscape was finished later that summer.[63][64]

2011 earthquake damage

On August 23, 2011, the Washington Monument sustained damage during the 5.8 magnitude 2011 Virginia earthquake;[65] over 150 cracks were found in the monument.[17] A National Park Service spokesperson reported that inspectors discovered a crack near the top of the structure, and announced that the monument would be closed indefinitely.[66][67] A block in the pyramidion also was partially dislodged, and pieces of stone, stone chips, mortar, and paint chips came free of the monument and "littered" the interior stairs and observation deck.[68] The Park Service said it was bringing in two structural engineering firms (Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. and Tipping Mar Associates) with extensive experience in historic buildings and earthquake-damaged structures to assess the monument.[69]

Officials said an examination of the monument's exterior revealed a "debris field" of mortar and pieces of stone around the base of the monument, and several "substantial" pieces of stone had fallen inside the memorial.[67] A crack in the central stone of the west face of the pyramidion was 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) long.[70][71] Park Service inspectors also discovered that the elevator system had been damaged, and was operating only to the 250-foot (76 m) level, but was soon repaired.[72]

On September 27, 2011, Denali National Park ranger Brandon Latham arrived to assist four climbers belonging to a "difficult access" team from Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates.[67][71] The reason for the inspection was the park agency's suspicion that there were more cracks on the monument's upper section not visible from the inside. The agency said it filled the cracks that occurred on August 23. After Hurricane Irene hit the area on August 27, water was discovered inside the memorial, leading the Park Service to suspect there was more undiscovered damage.[67] The rappellers used radios to report what they found to engineering experts on the ground.[73] Wiss, Janney, Elstner climber Dave Megerle took three hours to set up the rappelling equipment and set up a barrier around the monument's lightning rod system atop the pyramidion;[70] it was the first time the hatch in the pyramidion had been open since 2000.[70]

The external inspection of the monument was completed October 5, 2011. In addition to the 4-foot (1.2 m) long west crack, the inspection found several corner cracks and surface spalls (pieces of stone broken loose) at or near the top of the monument, and more loss of joint mortar lower down the monument. The full report was issued December 2011.[74] Bob Vogel, Superintendent of the National Mall and Memorial Parks, emphasized that the monument was not in danger of collapse. "It's structurally sound and not going anywhere", he told the national media at a press conference on September 26, 2011.[71]

More than $200,000 was spent between August 24 and September 26 inspecting the structure.[67] The National Park Service said that it would soon begin sealing the exterior cracks on the monument to protect it from rain and snow.[73][75]

On July 9, 2012, the National Park Service announced that the monument would be closed for repairs until 2014.[76] The National Park Service hired construction management firm Hill International in conjunction with joint-venture partner Louis Berger Group to provide coordination between the designer, Wiss, Janney, and Elstner Associates, the general contractor Perini, and numerous stakeholders.[77] NPS said a portion of the plaza at the base of the monument would be removed and scaffolding constructed around the exterior. In July 2013, lighting was added to the scaffolding.[78] Some stone pieces saved during the 2011 inspection will be refastened to the monument, while "Dutchman patches"[n 4] will be used in other places. Several of the stone lips that help hold the pyramidion's 2,000-pound (910 kg) exterior slabs in place were also damaged, so engineers will install metal brackets to more securely fasten them to the monument.[80]

The National Park Service reopened the Washington Monument to visitors on May 12, 2014, eight days ahead of schedule.[15][77] Repairs to the monument cost US$15,000,000,[17] with taxpayers funding $7.5 million of the cost and David Rubenstein funding the other $7.5 million.[18] At the reopening Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, Today show weatherman Al Roker, and American Idol Season 12 winner Candice Glover were present.[19]

Components

Cornerstone

The cornerstone was laid with great ceremony at the northeast corner of the lowest course or step of the old foundation on July 4, 1848. Robert Mills, the architect of the monument, stated in September 1848, "The foundations are now brought up nearly to the surface of the ground; the second step being nearly completed, which covers up the corner stone."[31]: 20 Therefore, the cornerstone was laid below the 1848 ground level. In 1880, the ground level was raised 17 feet (5.2 m) to the base of the shaft by the addition of a 30-foot (9.1 m) wide earthen embankment encircling the reinforced foundation, widened another 30 feet in 1881, and then the knoll was constructed in 1887–88.[6]: B-36–B-39 [31]: 70, 95–96 If the cornerstone was not moved during the strengthening of the foundation in 1879–80, its upper surface would now be 21 feet (6.4 m) below the pavement just outside the northeast corner of the shaft. It would now be sandwiched between the concrete slab under the old foundation and the concrete buttress completely encircling what remains of the old foundation. During the strengthening process, about half (by volume) of the periphery of the lowest seven of eight courses or steps of the old foundation (gneiss slabs) was removed to provide good footing for the buttress. Although a few diagrams, pictures and descriptions of this process exist, the fate of the cornerstone is not mentioned.[6]: 2-7–2-8, 3-3–3-5, 4-3–4-4, B-11–B-18, figs 2.5–2.7, 3.2–3.6, 3.13, 4.8–4.11 [31]: 67–73

The cornerstone was a 24,500-pound (11,100 kg) marble block 2.5 feet (0.76 m) high and 6.5 feet (2.0 m) square with a large hole for a zinc case filled with memorabilia. The hole was covered by a copper plate inscribed with the date of the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776), the date the cornerstone was laid (July 4, 1848), and the names of the managers of the Washington National Monument Society. The memorabilia in the zinc case included items associated with the monument, the city of Washington, the national government, state governments, benevolent societies, and George Washington, plus miscellaneous publications, both governmental and commercial, a coin set, and a bible, totaling 73 items or collections of items, as well as 71 newspapers containing articles relating to George Washington or the monument.[26]: app C [39]: pp 43–46, 109–166

The ceremony, which President James K. Polk supervised, began with a parade of dignitaries in carriages, marching troops, fire companies, and benevolent societies.[26]: chp 2 [39]: 44–48 [46][47]: 16–17, 45–47 A two-hour oration was delivered by the Speaker of the House of Representatives Robert C. Winthrop.[39]: 113–130 Then, the cornerstone was pronounced sound after a Masonic ceremony using George Washington's Masonic gavel, apron and sash, as well as other Masonic symbols. In attendance were Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, Mrs. Dolley Madison, Mrs. John Quincy Adams, and George Washington Parke Custis, among 15,000 to 20,000 others, including a bald eagle. The ceremony ended with fireworks that evening.

Memorial stones

States, cities, foreign countries, benevolent societies, other organizations, and individuals have contributed 194 memorial stones, all inserted into the east and west interior walls above stair landings or levels for easy viewing, except one on the south interior wall between stairs that is difficult to view. The sources disagree on the number of stones for two reasons: whether one or both "height stones" are included, and stones not yet on display at the time of a source's publication cannot be included. The "height stones" refer to two stones that indicate height: during the first phase of construction a stone with an inscription that includes the phrase "from the foundation to this height 100 feet" was installed just below the 80–90-foot stairway and high above the 60–70-foot stairway;[7]: sheet 25 [42]: 52 during the second phase of construction a stone with a horizontal line and the phrase "top of statue on Capitol" was installed on the 330-foot level.[7]: sheet 30 [81]

The Historic Structure Report (HSR, 2004) named 194 "memorial stones" by level, including both height stones.[6]: 4-17–4-20, 5–6, "194" on 4-17 Jacob (2005) described in detail and pictured 193 "commemorative stones", including the 100-foot stone but not the Capitol stone.[42]: "193" on 1 The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS, 1994) showed the location of 193 "memorial stones", but did not describe or name any. HABS showed both height stones, but did not show one stone not yet installed in 1994.[7]: sheets 22–25, 28–30 Olszewski (1971) named 190 "memorial stones" by level, including the Capitol stone but not the 100-foot stone. Olszewski did not include three stones not yet installed in 1971.[26]: chp 6, app D, "190" in chp 6

Of 194 stones, 95 are marble, 41 are granite, 30 are limestone, 9 are sandstone, with 19 miscellaneous types, including combinations of the aforesaid and those whose materials are not identified. Unusual materials include native copper (Michigan),[42]: 147 pipestone (Minnesota),[42]: 153 petrified wood (Arizona),[42]: 213 and jadeite (Alaska).[42]: 220 The stones vary in size from about 1.5 feet (0.46 m) square (Carthage)[n 5] to about 6 by 8 feet (1.8 m × 2.4 m) (Philadelphia and New York City).[42]: 3, 90, 124, 218

Utah contributed one stone as a territory and another as a state, both with inscriptions that include its pre-territorial name, Deseret, both located on the 220-foot level.[42]: 154–155

A stone at the 240-foot level of the monument is inscribed in Template:Lang-cy (My language, my land, my nation of Wales – Wales for ever). The stone, imported from Wales, was donated by Welsh citizens of New York.[83] Two other stones presented by the Sunday Schools of the Methodist Episcopal Church in New York and from the Sabbath School children of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, quote the Bible verses Proverbs 10:7, Proverbs 22:6, and Luke 17:6.[84][85]

Another inscription, this one sent by the Ottoman government,[42]: 128 combines the works of two eminent calligraphers: an imperial tughra by Mustafa Rakım's student Haşim Efendi, and an inscription in jalī ta'līq script by Kadıasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi, the calligrapher who wrote the giant medallions at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.[86][87]

One stone was donated by the Ryukyu Kingdom and brought back by Commodore Matthew C. Perry,[88] but never arrived in Washington (it was replaced in 1989).[42]: 210 Many of the stones donated for the monument carried inscriptions which did not commemorate George Washington. For example, one from the Templars of Honor and Temperance stated "We will not make, buy, sell, or use as a beverage, any spiritous or malt liquors, Wine, Cider, or any other Alcoholic Liquor."[42]: 140 (George Washington himself had owned a whiskey distillery which operated at Mount Vernon after he left the presidency.[89])

Aluminum apex

The aluminum apex, at the time a rare metal as valuable as silver, was cast by William Frishmuth of Philadelphia.[10] Before the installation it was put on public display at Tiffany's in New York City and stepped over by visitors who could say they had "stepped over the top of the Washington Monument". It was 8.9 inches (23 cm) tall before 3⁄8 inch was removed from its tip by lightning strikes during 1885–1934, when it was protected from further damage by tall lightning rods surrounding it. Its base is 5.6 inches (14 cm) square. The angle between opposite sides at its tip is 34°48'. It weighed 100 ounces (2.83 kg) before lightning strikes removed a small amount of aluminum from its tip and sides.[90] Spectral analysis in 1934 showed that it was composed of 97.87% aluminum with the rest impurities.[10] It has a shallow depression in its base to match a slightly raised area atop the small upper surface of the marble capstone, which aligns the sides of the apex with those of the capstone, and the downward protruding lip around that area prevents water from entering the joint.[31]: 83–84 It has a large hole in the center of its base to receive a threaded 1.5-inch (3.8 cm) diameter copper rod which attaches it to the monument and used to form part of the lightning protection system.[31]: 91

The four faces of the external aluminum apex all bear inscriptions in cursive writing (Snell Round hand), which are incised into the aluminum.[10] Most inscriptions are the original 1884 inscriptions, except for the top three lines on the east face which were added in 1934. A wide gold-plated copper band that held eight lightning rods covered most of the inscriptions from 1885 until it was removed and discarded in 2013. The inscriptions that it covered were damaged and are now illegible. Only the top four and bottom two lines of the north face, the first and last lines of the west face, the top four lines of the south face, and the top three lines of the east face are still legible. Even though the inscriptions are no longer covered, no attempt was made to repair them when the apex was accessible in 2013. The following table shows legible inscriptions in blue and illegible inscriptions in red.[1]: 93 No colors appear on the actual apex.

| North face | West face | South face | East face |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Commission at Setting of Cap Stone. String Module Error: function rep expects a number as second parameter, received "—" Chester A. Arthur. W. W. Corcoran, Chairman. M. E. Bell. Edward Clark. John Newton. Act of August 2, 1876. |

Corner Stone Laid on Bed of Foundation July 4, 1848. First Stone at Height of 152 feet laid August 7, 1880. Capstone set December 6, 1884. |

Chief Engineer and Architect, Thos. Lincoln Casey, Colonel, Corps of Engineers. Assistants: George W. Davis, Captain, 14th Infantry. Bernard R. Green, Civil Engineer. Master Mechanic, P. H. McLaughlin. |

Repaired 1934, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Laus Deo. |

Although most printed sources, Harvey (1903),[39]: 295 Olszewski (1971),[26]: app C Torres (1984),[31]: 82, 84 and the Historic Structure Report (2004),[6]: 4-6–4-7 refer to the original 1884 inscriptions, the National Geodetic Survey (2015)[1]: 90–95 refers to both the 1884 and 1934 inscriptions. All sources print them according to their own editorial rules, resulting in excessive capitalization (Harvey, Olszewski, and NGS) and inappropriate line breaks. No printed source uses cursive writing, although pictures of the apex clearly show that it was used for both the 1884 and 1934 inscriptions.[1]: 92–95 [91][92]

A replica displayed on the 490-foot level uses totally different line breaks than those on the external apex — it also omits the 1934 inscriptions. In October 2007, it was discovered that the display of this replica was positioned so that the Laus Deo (Latin for "praise be to God") inscription could not be seen and Laus Deo was omitted from the placard describing the apex. The National Park Service rectified the omission by creating a new display.[93]

Lightning protection

The pyramidion, the pointed top 55 feet (17 m) of the monument, was originally designed with an 8.9-inch (23 cm) tall inscribed aluminum apex which served as a single lightning rod, installed December 6, 1884. Six months later on June 5, 1885 lightning damaged the marble blocks of the pyramidion,[94] so a net of gold-plated copper rods supporting 200 3-inch (7.6 cm) gold-plated, platinum-tipped copper points spaced every 5 feet (1.5 m) was installed over the entire pyramidion.[6]: 3-10–3-11, 3–15, figs 3.17, 3.23 [26]: chp 6 [31]: 91–92 The original net included a gold-plated copper band attached to the aluminum apex by four large set screws which supported eight closely spaced vertical points that did not protrude above the apex. In 1934 these eight short points were lengthened to extend them above the apex by 6 inches (15 cm).[95] In 2013 this original system was removed and discarded. It was replaced by only two thick solid aluminum lightning rods protruding above the tip of the apex by about one foot (0.3 m) attached to the east and west sides of the marble capstone just below the apex.[11][1]: 23, 26

Until it was removed, the original lightning protection system was connected to the tops of the four iron columns supporting the elevator with large copper rods. Even though the aluminum apex is still connected to the columns with large copper rods, it is no longer part of the lightning protection system because it is now disconnected from the present lightning rods which shield it. The two lightning rods present since 2013 are connected to the iron columns with two large braided aluminum cables leading down the surface of the pyramidion near its southeast and northwest corners. They enter the pyramidion at its base, where they are tied together (electrically shorted) via large braided aluminum cables encircling the pyramidion two feet (0.6 m) above its base.[11] The bottom of the iron columns are connected to ground water below the monument via four large copper rods that pass through a 2-foot (0.6 m) square well half filled with sand in the center of the foundation. The effectiveness of the lightning protection system has not been affected by a significant draw down of the water table since 1884 because the soil's water content remains roughly 20% both above and below the height of the water table.[96]

Flags

Fifty American flags (not state flags), one for each state, are now flown 24 hours a day around a large circle centered on the monument. Forty eight American flags (one for each state then in existence) were flown on wooden flag poles on Washington's birthday since 1920 and later on Independence Day, Memorial Day, and other special occasions until early 1958. Both the flags and flag poles were removed and stored between these days. In 1958 fifty 25-foot (7.6 m) tall aluminum flag poles (anticipating Alaska and Hawaii) were installed, evenly spaced around a 260-foot (79 m) diameter circle. During 2004–05, the diameter of the circle was reduced to 240 feet (73 m). Since Washington's birthday 1958, 48 American flags were flown on a daily basis, increasing to 49 flags on July 4, 1959, and then to 50 flags since July 4, 1960. When 48 and 49 flags were flown, only 48 and 49 flag poles of the available 50 were placed into base receptacles. All flags were removed and stored overnight. Since July 4, 1971, 50 American flags have flown 24 hours a day.[6]: 2-14–2-15, 4-1–4-2, B-35–B-36 [7]: sheet 3 [97]

Security

In 2001, a temporary visitor security screening center was added to the east entrance of the Washington Monument in the wake of the September 11 attacks. The one-story facility was designed to reduce the ability of a terrorist attack on the interior of the monument, or an attempt to seize and hold it. Visitors obtained their timed-entry tickets from the Monument Lodge east of the memorial, and passed through metal detectors and bomb-sniffing sensors prior to entering the monument. After exiting the monument, they passed through a turnstile to prevent them from re-entering. This facility, a one-story cube of wood around a metal frame, was intended to be temporary until a new screening facility could be designed.[98]

On March 6, 2014, the National Capital Planning Commission approved a new visitor screening facility to replace the temporary one. The 785-square-foot (72.9 m2) facility will be two stories high and contain space for screening 20 to 25 visitors at a time. The exterior walls (which will be slightly frosted to prevent viewing of the security screening process) will consist of an outer sheet of bulletproof glass or polycarbonate, a metal mesh insert, and another sheet of bulletproof glass. The inner sheet will consist of two sheets (slightly separated) of laminated glass. A 0.5-inch (1.3 cm) airspace will exist between the inner and outer glass walls to help insulate the facility. Two (possibly three) geothermal heat pumps will be built on the north side of the monument to provide heating and cooling of the facility. The new facility will also provide an office for National Park Service and United States Park Police staff. The structure is designed so that it may be removed without damaging the monument.[99] The United States Commission of Fine Arts approved the aesthetic design of the screening facility in June 2013.[100]

A recessed trench wall known as a ha-ha has been built to minimize the visual impact of a security barrier surrounding the monument. After the September 11 attacks and another unrelated terror threat at the monument, authorities had put up a circle of temporary Jersey barriers to prevent large motor vehicles from approaching. The unsightly barrier was replaced by a less-obtrusive low 30-inch (0.76 m) granite stone wall that doubles as a seating bench and also incorporates lighting. The installation received the 2005 Park/Landscape Award of Merit from the American Society of Landscape Architects.[101][102][103]

Construction details

The completed monument has the following construction materials and details:

- Phase One (1848 to 1858): To the 152-foot (46 m) level, under the direction of Superintendent William Daugherty.

- Exterior: White marble from Texas quarry, Maryland (adjacent to and east of north I-83 near the Warren Road exit in Cockeysville). Two defective courses at the 154–156-foot levels added by the Know-Nothings and the last 152-foot course added by Daugherty were removed by Casey before phase two construction of the shaft resumed.

- Phase Two (1878 to 1888): Work completed under the direction of Lt. Col./Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

- Exterior: White marble, three courses or rows at the 152–156-foot (46–48 m) levels, from Sheffield, Massachusetts.

- Exterior: White marble above 156 feet from Beaver Dam Quarry (now Beaverdam Pond) near Cockeysville, Maryland.[31]: 63 [104][105][106]

- Structural: marble (0–555 feet (0–169 m)), bluestone gneiss (below 150 feet (46 m)), granite (150–450 feet (46–137 m)), concrete (below ground, unreinforced)[3]

- Cost of the monument during 1848–85: $1,187,710

Cost of the monument during 1848–88: $1,409,500[107]

Exterior structure

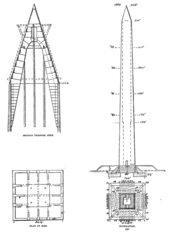

- Total height of monument: 554 ft 7+11⁄32 in (169.046 m)[n 1]

- Height from base of shaft to floor of observation level: 500 feet (152 m)

- Width at base of monument: 55 ft 1+1⁄2 in (16.802 m)

- Width at top of shaft: 34 ft 5+5⁄8 in (10.506 m)

- Thickness of monument walls at base: 15 feet (4.6 m)

- Thickness of monument walls at top of shaft: 18 inches (46 cm)

- Thickness of monument walls in pyramidion: 7 inches (18 cm)[31]: 85

- Total weight of monument (including foundation): 81,120 long tons (90,854 short tons; 82,422 tonnes)

- Total weight of monument (excluding foundation): 44,208 long tons (49,513 short tons; 44,917 tonnes)

- Total number of blocks in monument: over 36,000[8]

- Includes all marble, granite and gneiss blocks, whether externally or internally visible or hidden from view within the walls or old foundation. The number of marble blocks externally visible is about 10,000.

- Sway of monument in 30-mile-per-hour (48 km/h) wind: 0.125 inches (3.2 mm)

Capstone

- Marble capstone weight: 3,300 pounds (1.5 t)*

- Capstone cuneiform keystone measures 5.16 feet (1.57 m) from base to the top

- Each side of the capstone base: 3 feet (0.91 m)

Foundation

- Depth: 36 ft 10 in (11.23 m)

- Consisting of the 23.5-foot thick gneiss-block old foundation and a 13.5-foot thick concrete slab below it.

- Weight: 36,912 long tons (41,341 short tons; 37,504 tonnes)

- Includes earth and gneiss rubble above the concrete foundation that is within its 126.5 feet (38.6 m) square perimeter.

- Area: 16,002 square feet (1,486.6 m2)

Interior

- Present elevator installed: 1998

- Present elevator cab installed: 2001

- Elevator travel time: 70 seconds

- Number of steps in stairwell: 897 since 1958;[6]: fig 3.35 [8] 898 before 1958[26]: chp 7 [107]

- Originally, the monument had 49 flights of stairs up to the 490-foot level with 18 steps or risers per flight,[7]: sheets 31–35 plus a 490–500-foot spiral stairway with 16 steps in the northeast corner.[31]: 72 In 1958, the original spiral stairway was replaced with two 490–500-foot spiral stairways of a different design with 15 steps each in the northeast and southeast corners.[6]: 3–17, B-48 [7]: sheet 6 Only one spiral's steps are counted. These figures do not include a step in the entrance passage that was replaced by a ramp in 1975.[6]: 3–18, B-49, figs 3.11, 3.27, 3.32, 3.33

Transit

The Washington Monument is served by the Smithsonian metro station, located on Independence Avenue.

In popular culture

As a landmark of the U.S. capital, the Washington Monument has been featured in film and television depictions. The symbolic meaning of the shape is referenced in the novel The Lost Symbol by Dan Brown.[108] The monument is also the subject of Carl Sandburg's 1922 poem, "Washington by Night".[109]

See also

- List of public art in Washington, D.C., Ward 2

- List of tallest freestanding structures in the world

- List of tallest towers in the world

- Yule Marble

Washington, D.C. portal

Washington, D.C. portal Architecture portal

Architecture portal

Notes

- ^ a b

Several heights have been specified, all of which exclude the foundation whose top is 17 feet (5.2 m) above the pre-construction ground level. The foundation is surrounded by a grassy knoll which effectively places the foundation below ground level. This knoll serves as a buttress for the foundation.

- 554 feet 7+11⁄32 inches (169.046 m) given above, according to the National Geodetic Survey (NGS)[1]: 5 using the criteria of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), that is, from the "level of the lowest, significant, open-air, pedestrian entrance" to the highest point of the building.[4] From among four candidate points suggested by the NGS, the CTBUH chose a point on the entrance ramp installed in 1975 where it crosses the outer face of the marble facade of the monument.[3]: 7 [5][6]: 2–15, 3–18, 4–13, B-49, figs 3.32, 3.33, 3.39, 3.42 [7]: sheet 31 Reported February 16, 2015. This is also its new above ground height because the ground at the shaft was raised in 1975 to match the ramp. The ground surrounding the shaft was replaced by granite pavers during 2004–05 to match the raised ground level and the ramp. This height is 22.0 centimeters (8.66 in) above four "CASEY marks", 2.5-inch (6.4 cm) diameter brass bolts inserted into the topmost level of the foundation just outside the four corners of the monument and set flush with the lower surface of the marble blocks, that the NGS thinks were likely used by Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey, the engineer in charge of construction, to determine the traditional height in 1884. The floor at the elevator is now 13.9 centimeters (5.47 in) above this pedestrian entrance, and 35.9 centimeters (14.13 in) above the CASEY marks.[1]: 13, 56, 65, 82–84 The highest point of the monument is a one millimeter diameter dimple atop the aluminum apex.

- 555 feet 5+1⁄8 inches (169.294 m) according to the National Park Service.[8] Reported in 1884 by Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey, the engineer in charge of construction.[9] It was measured from the top of the foundation (the lowest marble joint or the door-sills of the two empty doorways), which was in place in 1884. This is the traditional height of the monument that became moot when the pavement or ground next to the monument was raised in 1975.

- 554 feet 11+1⁄2 inches (169.151 m) according to architectural drawings in the Historic American Buildings Survey (1994), pavement at shaft to tip.[7]: sheets 7, 31 This height is comparable to the NGS height because it was also determined after the ramp was installed in 1975.

- ^ a b

Two other monumental columns have heights comparable to that of the Washington Monument, the San Jacinto Monument in Texas and the Juche Tower in North Korea. Which of the three is taller depends on how its height is measured. A traditional method is above a part of the monument comparable to ground level. A more recent method is that used by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), the arbiter of the height of tall buildings since 1969. The CTBUH states the height of a building must be measured above the "level of the lowest, significant, open-air, pedestrian entrance".[4] The three CTBUH (above pedestrian entrance) heights from tallest to shortest are the Washington Monument, the San Jacinto Monument (−2.6 feet (−0.79 m)), and the Juche Tower (−6 meters (−20 ft)). The above ground heights of the three monumental columns from tallest to shortest are the San Jacinto Monument (+12.70 feet (3.871 m)), the Juche Tower (+1 meter (3.3 ft)), and the Washington Monument. Height differences are relative to the height of the Washington Monument.

- The Washington Monument's CTBUH (above pedestrian entrance) height, 554 feet 7+11⁄32 inches (169.046 m), is the same as its above ground height.

- The San Jacinto Monument has a surveyed height of 567.31 feet (172.916 m) from its footing to the top of its beacon. However, the architect of the monument, Albert C. Finn, stated, "San Jacinto ... is actually 552 feet (168.2 m) from the first floor to the top of the beacon" ... in the "customary way" of measuring such things.[12] The "first floor" is the CTBUH criterion. A stepped terrace elevates this pedestrian entrance above ground, thus reducing the monument's remaining height by its thickness, about 15.5 feet (4.7 m), to the monument's CTBUH height. The monument is made of reinforced concrete, not stone, although it has a facade of limestone.

- The Juche Tower has a specified height of 170 meters (558 ft) above a very large concrete bus parking lot just east of the tower. A stepped terrace elevates its pedestrian entrance, also on its east side, above this ground level. Its thickness, 7 meters (23 ft), reduces the remaining height of the tower to 163 meters (535 ft), its CTBUH height. The tower is made of reinforced concrete, not stone, although it has a facade of granite. A metal cage holding many panels of red glass in the shape of a flame, internally illuminated at night, surmounting a gold-colored "fuel chamber", occupies its top 20 meters (66 ft).

- ^ L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life, while residing in the US. He wrote this name on his "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ..." and on other legal documents.[32] However, during the early 1900s, a French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant".[33] The National Park Service identifies L'Enfant as "Major Peter Charles L'Enfant" and as "Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant" on pages of its website that describe the Washington Monument.[34][35] The United States Code states in 40 U.S.C. § 3309: "(a) In General.—The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant."

- ^ A "Dutchman Repair" "is a type of partial replacement or 'piecing-in'" that "involves replacing a small area of damaged stone" with a small piece of natural or imitation stone, "wedged in place or secured with an adhesive", with the joint being "as narrow as possible to maintain the appearance of a continuous surface."[79]

- ^ The Carthage stone was the last memorial stone installed in the monument, in 2000.[82]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Geodetic Survey, "2013–2014 Survey of the Washington Monument", 2015. Horizontal coordinates converted from NAD83(2011) to WGS84(G1674), the required coordinate system for Wikipedia coordinates, via NGS Horizontal Time-Dependent Positioning, epoch 2010.0 including ellipsoidal height.

- ^ "Foundation Statement for the National Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Park" (PDF), National Park Service, retrieved May 20, 2010

- ^ a b c Wunsch, Aaron V. (1994). Historic American Buildings Survey, Washington Monument, HABS DC-428 (text) (PDF). National Park Service.

- ^ a b "CTBUH Criteria for Defining and Measuring Tall Buildings". ctbuh.org.

- ^ National Geodetic Survey, "Why does the value obtained in 2014 ... disagree with the 1884 value ...?", 2015, picture of precise spot used.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j John Milner Associates, Historic Structure Report: Washington Monument, 2004 (HSR)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arzola, Robert R.; Lockett, Dana L.; Schara, Mark; Vazquez, Jose Raul (1994). Historic American Buildings Survey, Washington Monument, HABS DC-428 (drawings). National Park Service.

- ^ a b c "Frequently Asked Questions about the Washington Monument by the National Park Service". Nps.gov. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Thos. Lincoln Casey, "report of operations upon the Washington Monument for the year [1884]" in Letter from William W. Corcoran, Chairman of the Joint Commission for the Completion of the Washington Monument, transmitting the annual report of the Commission, December 19, 1884, U.S. Congressional Serial Set, Vol. 2310, 48th Congress, 2nd Session, House of Representatives Misc. Doc. 8, p. 5. Available in most large United States libraries in government documents or online. Establish a connection to Readex collections before clicking on link.

- ^ a b c d e George J. Binczewski (1995). "The Point of a Monument: A History of the Aluminum Cap of the Washington Monument". JOM. 47 (11): 20–25. doi:10.1007/bf03221302.

- ^ a b c "Aerial America: Washington D.C.". Aerial America. Smithsonian channel.

- ^ Paul Gervais Bell Jr., "Monumental Myths", Southwestern Historical Quarterly", vol. 103, 2000, frontispiece-14, pp. 13-14

- ^ a b Marking a people's love, an article from The New York Times published February 22, 1885.

- ^ ""Washington Monument Remains Closed Indefinitely." ''Associated Press.''". Photoblog.msnbc.msn.com. August 23, 2011. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Washington Monument reopening". National Park Service. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Photos From the Top of the Washington Monument Reopening". I Hit The Button. May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Washington Monument reopens after quake repairs". CNN.com. August 23, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "10 Facts About the Washington Monument as It Reopens". ABC News. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "Washington Monument draws crowds as it reopens after renovations". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (November 2002). "Founding Fathers and Slaveholders". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Paul K. Longmore (1999). The Invention of George Washington. Univ. of Virginia Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8139-1872-3. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Sheldon S. Cohen, "Monuments to Greatness: George Dance, Charles Polhill, and Benjamin West's Design for a Memorial to George Washington." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, April 1991, Vol. 99 Issue 2, pp. 187–203. JSTOR 4249215 ISSN 0042-6636Template:Accessdate

- ^ Kirk Savage, Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (2009) pp 32–45

- ^ George Cochrane Hazelton, The national capitol: its architecture, art and history (1902) p. 288.

- ^ a b "The Washington Monument: Tribute in Stone". National Park Service, ParkNet.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Olszewski, George J. (1971). "A History of the Washington Monument, 1844–1968, Washington, D.C." Washington, D.C.: National Park Service.

- ^ a b "The Washington Monument: Tribute in Stone, Reading 3". National Park Service. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ^ "Drawing 1: Robert Mills's design for the Washington Monument. Photo 1: The Washington Monument today.", National Park Service. Accessed 2015-03-07.

- ^ Richard G. Carrot, The Egyptian Revival, University of California press, 1978 plate 33

- ^ Download Conversion Factors Oregon State University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Louis Torres, "To the immortal name and memory of George Washington": The United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Construction of the Washington Monument, (Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1984).

- ^ a b Peter Charles L'Enfant's "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ..." in official website of the U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 22, 2009. Freedom Plaza in downtown Washington, D.C., contains an inlay of the central portion of L'Enfant's plan and of its legends. Template:WebCite

- ^ Bowling, Kenneth R (2002). Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic. George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

- ^ "Washington Monument" section in "Washington, D.C.: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary" page in official website of U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ "Washington Monument" page in "American Presidents" section of official website of U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ "Data Sheet Retrieval". noaa.gov.

- ^ Pfanz, Donald C., National Park Service, National Capital Region (December 2, 1980). "Jefferson Pier Marker". National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Washington Monument. United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service. p. Continuation Sheet, Item No. 7, p. 4. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Reeves, Thomas C. (February 1975). Gentleman Boss. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Frederick L. Harvey, History of the Washington National Monument and Washington National Monument Society, Congressional Serial Set, volume 4436, 57th Congress, 2nd session, Senate Doc. 224, 1903. This 1903 edition is about three times the size of the 1902 edition, which has the slightly different name History of the Washington National Monument and of the Washington National Monument Society. The 1903 edition is available in most large United States libraries in government documents or online. Establish a connection to Readex collections before clicking on 1903 link.

- ^ a b "Reading 2: Construction of the Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Perry, John (2010). Lee: A Life of Virtue. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1595550283. OCLC 456177249. At Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Judith M. Jacob, The Washington Monument: A technical history and catalog of the commemorative stones, 2005.

- ^ "Washington Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

The walls of the monument range in thickness from 15' at the base to 18 at the upper shaft. They are composed primarily of white marble blocks from Maryland with a few from Massachusetts, underlain by Maryland blue gneiss and Maine granite. A slight color change is perceptible at the 150' level near where construction slowed in 1854.

- ^ "Hall Process: Production and Commercialization of Aluminum". National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "Washington Monument". Teaching with Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved October 15, 2006.

- ^ a b c Crutchfield, James A. (2005). George Washington: First in War, First in Peace. New York, N.Y.: A Forge Book: Tom Doherty Associates, LLC. p. 218. ISBN 0765310708. OCLC 269434694.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|2=,|3=, and|4=(help) At Google Books. - ^ a b The Dedication of the Washington National Monument, 1885.

- ^ Reeves, Thomas C. (February 1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ^ B. Philip Bigler. "Washington Monument". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

At its completion in 1884 it was the world's tallest man-made structure, though it was supplanted by the Eiffel Tower just five years later. It remains the world's tallest masonry structure.

- ^ "Washington Monument". Emporis.com. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ^ "Washington Monument". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- ^ "Primary Acts passed by U.S. Congress". Loislaw. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Edward Chaney, "Roma Britannica and the Cultural Memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the Obelisk of Domitian", in Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, K. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–70.

- ^ "Determining the Facts Reading 3: Finishing the Monument". nps.gov. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "Monthly Visitors to the Washington Monument". The New York Times. August 24, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Washington Monument attacked by Geological Tuberculosis" Popular Mechanics, December 1911, pp. 829–830. This source mistakenly said the lower 190 feet was constructed during the early period — it was actually 150 feet.

- ^ Jeffrey David Simon (2001). The Terrorist Trap: America's Experience with Terrorism. Indiana UP. p. 285.

- ^ Gabriel Escobar (December 30, 1998). "Obelisk's Scaffold Is First of Its Kind". Washington Post. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Linda Wheeler (July 30, 2000). "It's Ready for Its Close-Up Now: Big Crowds Are Expected For Monument's Reopening". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Metro in Brief". The Washington Post. August 30, 2000.

- ^ John Heilprin (February 23, 2002). "New sight from Washington Monument". Deseret News. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Washington Monument reopens to public". USA Today. April 1, 2005. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Paul Schwartzman (March 19, 2005). "Washington Monument To Reopen Next Month". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ FoxNews.com (August 23, 2011). "Disasters Washington Monument Indefinitely Closes After Earthquake Causes Cracks". Fox News. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ "Washington Monument top cracked by earthquake". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 17, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Michael E. Ruane (September 26, 2011). "Washington Monument Elevator Damage Inspected as Earthquake's Toll Is Assessed". Washington Post. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia. "Washington Monument Cracks Indicate Earthquake Damage." Washington Post. August 25, 2011. Assessed August 26, 2011.

- ^ "Washington Monument Finds Additional Cracks." Press release. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c Nuckols, Ben. "Weather May Delay Washington Monument Rappelling" Associated Press. September 27, 2011. Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c O'Toole, Molly. "Engineers to Rappel Down Washington Monument to Inspect Damage". Reuters.com. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Clark, Charles S. (August 21, 2012). "Washington Monument Elevator Woes". Government Executive. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b Smith, Markette (September 26, 2011). "Climbers Rappel Washington Monument to Assess Damage". Wamu.org. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ "Post-Earthquake Assessment" (PDF). www.nps.gov. National Park Service. December 22, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ Washington Monument Earthquake Update, NPS, page contains news releases, a picture, video, and images of the earthquake and damage

- ^ Cohn, Alicia. "Washington Monument could be closed until 2014 for earthquake repairs". The Hill. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "Washington Monument Earthquake Repair". CMAA. May 1, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Freed, Benjamin R. "Washington Monument Nearly Topped Out, Will Be Lighted in June". Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ Grimmer, Anne E., "Dutchman Repair" (1984),A Glossary of Historic Masonry Deterioration Problems and Preservation Treatments. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service Preservation Assistance Division. p. 56. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ Ruane, Michael E. "Earthquake-Damaged Washington Monument May Be Closed Into 2014." Washington Post. July 9, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012

- ^ "Inscription at level 330 - Washington Monument, High ground West of Fifteenth Street, Northwest, between Independence & Constitution Avenues, Washington, District of Columbia, DC". loc.gov.

- ^ "The Washington Monument's Inner Jewels", nps.gov

- ^ The Cambrian, vol. XVII, p. 139. 1897.

- ^ "Laus Deo". Just4kidsmagazine.com. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ "Religious significance of George Washington and the Washington memorial-Mostly Truth!". Truthorfiction.com. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Kadiasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi (1801–76) Journal of Ottoman Calligraphy

- ^ "Sister Monuments : Hagia Sophia and Washington Monument". (not to be) Missed Turkey & Istanbul Sites and Facts.

- ^ Kerr, George H. Okinawa: The History of an Island People. (revised ed.) Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2003. p337n.

- ^ Ferling, John E. (1988). The First of Men: A Life of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 488. ISBN 0199742278. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ [Thomas Lincoln Casey], Letter from the Joint Commission for Completion of the Washington Monument, transmitting their annual report. December 15, 1885 Congressional Serial Set, volume 2333, 49th Congress, 1st session, Senate Doc. 6. Available in most large United States libraries in government documents or online. Establish a connection to Readex collections before clicking on link.

- ^ External apex east and north faces

- ^ External apex west and south faces Horydczak collection – Washington Monument 119–127

- ^ "A Monumental Omission". Nationaltreasures.org. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ M., "The Washington Monument, and the Lightning Stroke of June 5", Science 5 (1885) 517–518.

- ^ Gabriel Escobar, "Workers prepare to fill a tall order", Washington Post Tuesday, October 13, 1998, page B1.

- ^ Jean-Louis Briaud et al, "The Washington Monument case history", International Journal of Geoengineering Case Histories 1 (2009) 170–188, pp. 176–179.

- ^ Michael D. Hoover, The origins and history of the Washington Monument flag display, 1992

- ^ National Park Service and National Capital Planning Commission. "Visitor Screening Facility, Washington Monument Between 14th and 17th Streets, NW and Constitution Avenue, NW and the Tidal Basin." Executive Director's Recommendation. NCPC File Number 6176. March 6, 2014, pp. 5, 7. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Neibauer, Michael. "Here's Where You'll Queue to Visit the Washington Monument." Washington Business Journal. March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ National Park Service and National Capital Planning Commission. "Visitor Screening Facility, Washington Monument Between 14th and 17th Streets, NW and Constitution Avenue, NW and the Tidal Basin." Executive Director's Recommendation. NCPC File Number 6176. March 6, 2014, pp. 15-16. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Washington Monument (from the OLIN website)

- ^ Monumental Security (from the American Society of Landscape Architects website, April 10, 2006)

- ^ Risk Management Series: Site and Urban Design for Security. U. S. Department Security, Federal Emergency Agency. pp. 4–17.

- ^ "History of Beaver Dam Quarries" (PDF). Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ "Marble quarries near Cockeysville, MD" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ William D. Purdum (March 5, 1940). "The history of the marble quarries in Baltimore County, Maryland". Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Charles W. Snell, A Brief History of the Washington Monument and Grounds, 1783–1978 (1978) 17–19.

- ^ Christopher Hodapp (January 13, 2010). Deciphering the Lost Symbol: Freemasons, Myths and the Mysteries of Washington. Ulysses Press. ISBN 978-1-56975-773-4.

- ^ Sandburg, Carl. "Washington Monument by Night".

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links

- Official NPS website: Washington Monument

- "Trust for the National Mall: Washington Monument". Trust for the National Mall.

- Harper's Weekly cartoon, February 21, 1885, the day of formal dedication

- Today in History—December 6

- Washington National Monument at Structurae

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DC-428, "Washington Monument"

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. DC-5, "Washington Monument"

- Prehistory on the Mall at the Washington Monument

Cite error: There are <ref group=[[Category:Pages with errors in inflation template]]> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=[[Category:Pages with errors in inflation template]]}} template (see the help page).

- 1888 establishments in the United States

- Buildings and monuments honoring American Presidents

- Buildings and structures completed in 1888

- Former world's tallest buildings

- George Washington

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Washington, D.C.

- Historic American Engineering Record in Washington, D.C.

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- IUCN protected area errors

- Monuments and memorials on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington, D.C.

- National Mall and Memorial Parks

- National Memorials of the United States

- Obelisks in the United States

- Robert Mills buildings

- Terminating vistas in the United States

- Towers in Washington, D.C.