Wind turbine

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

A wind turbine is a device that converts kinetic energy from the wind into electrical power. A wind turbine used for charging batteries may be referred to as a wind charger.

The result of over a millennium of windmill development and modern engineering, today's wind turbines are manufactured in a wide range of vertical and horizontal axis types. The smallest turbines are used for applications such as battery charging for auxiliary power for boats or caravans or to power traffic warning signs. Slightly larger turbines can be used for making small contributions to a domestic power supply while selling unused power back to the utility supplier via the electrical grid. Arrays of large turbines, known as wind farms, are becoming an increasingly important source of renewable energy and are used by many countries as part of a strategy to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels.

History

Windmills were used in Persia (present-day Iran) as early as 200 B.C.[1] The windwheel of Hero of Alexandria marks one of the first known instances of wind powering a machine in history.[2][3] However, the first known practical windmills were built in Sistan, an Eastern province of Iran, from the 7th century. These "Panemone" were vertical axle windmills, which had long vertical drive shafts with rectangular blades.[4] Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind grain or draw up water, and were used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries.[5]

Windmills first appeared in Europe during the Middle Ages. The first historical records of their use in England date to the 11th or 12th centuries and there are reports of German crusaders taking their windmill-making skills to Syria around 1190.[6] By the 14th century, Dutch windmills were in use to drain areas of the Rhine delta.

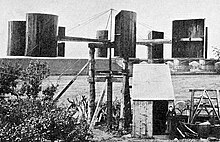

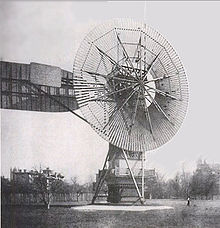

The first electricity-generating wind turbine was a battery charging machine installed in July 1887 by Scottish academic James Blyth to light his holiday home in Marykirk, Scotland.[7] Some months later American inventor Charles F. Brush built the first automatically operated wind turbine for electricity production in Cleveland, Ohio.[7] Although Blyth's turbine was considered uneconomical in the United Kingdom[7] electricity generation by wind turbines was more cost effective in countries with widely scattered populations.[6]

In Denmark by 1900, there were about 2500 windmills for mechanical loads such as pumps and mills, producing an estimated combined peak power of about 30 MW. The largest machines were on 24-meter (79 ft) towers with four-bladed 23-meter (75 ft) diameter rotors. By 1908 there were 72 wind-driven electric generators operating in the United States from 5 kW to 25 kW. Around the time of World War I, American windmill makers were producing 100,000 farm windmills each year, mostly for water-pumping.[9]

By the 1930s, wind generators for electricity were common on farms, mostly in the United States where distribution systems had not yet been installed. In this period, high-tensile steel was cheap, and the generators were placed atop prefabricated open steel lattice towers.

A forerunner of modern horizontal-axis wind generators was in service at Yalta, USSR in 1931. This was a 100 kW generator on a 30-meter (98 ft) tower, connected to the local 6.3 kV distribution system. It was reported to have an annual capacity factor of 32 percent, not much different from current wind machines.[10]

In the autumn of 1941, the first megawatt-class wind turbine was synchronized to a utility grid in Vermont. The Smith-Putnam wind turbine only ran for 1,100 hours before suffering a critical failure. The unit was not repaired, because of shortage of materials during the war.

The first utility grid-connected wind turbine to operate in the UK was built by John Brown & Company in 1951 in the Orkney Islands.[7][11]

Despite these diverse developments, developments in fossil fuel systems almost entirely eliminated any wind turbine systems larger than supermicro size. In the early 1970s, however, anti-nuclear protests in Denmark spurred artisan mechanics to develop microturbines of 22 kW. Organizing owners into associations and co-operatives lead to the lobbying of the government and utilities and provided incentives for larger turbines throughout the 1980s and later. Local activists in Germany, nascent turbine manufacturers in Spain, and large investors in the United States in the early 1990s then lobbied for policies that stimulated the industry in those countries. Later companies formed in India and China. As of 2012, Danish company Vestas is the world's biggest wind-turbine manufacturer.

Resources

A quantitative measure of the wind energy available at any location is called the Wind Power Density (WPD) It is a calculation of the mean annual power available per square meter of swept area of a turbine, and is tabulated for different heights above ground. Calculation of wind power density includes the effect of wind velocity and air density. Color-coded maps are prepared for a particular area described, for example, as "Mean Annual Power Density at 50 Metres". In the United States, the results of the above calculation are included in an index developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and referred to as "NREL CLASS". The larger the WPD calculation, the higher it is rated by class. Classes range from Class 1 (200 watts per square meter or less at 50 m altitude) to Class 7 (800 to 2000 watts per square m). Commercial wind farms generally are sited in Class 3 or higher areas, although isolated points in an otherwise Class 1 area may be practical to exploit.[12]

Wind turbines are classified by the wind speed they are designed for, from class I to class IV, with A or B referring to the turbulence.[13]

| Class | Avg Wind Speed (m/s) | Turbulence |

|---|---|---|

| IA | 10 | 18% |

| IB | 10 | 16% |

| IIA | 8.5 | 18% |

| IIB | 8.5 | 16% |

| IIIA | 7.5 | 18% |

| IIIB | 7.5 | 16% |

| IVA | 6 | 18% |

| IVB | 6 | 16% |

Efficiency

Not all the energy of blowing wind can be harvested, since conservation of mass requires that as much mass of air exits the turbine as enters it. Betz's law gives the maximal achievable extraction of wind power by a wind turbine as 59% of the total kinetic energy of the air flowing through the turbine.[14]

Further inefficiencies, such as rotor blade friction and drag, gearbox losses, generator and converter losses, reduce the power delivered by a wind turbine. Commercial utility-connected turbines deliver about 75% of the Betz limit of power extractable from the wind, at rated operating speed.

Efficiency can decrease slightly over time due to wear. Analysis of 3128 wind turbines older than 10 years in Denmark showed that half of the turbines had no decrease, while the other half saw a production decrease of 1.2% per year.[15]

Types

Wind turbines can rotate about either a horizontal or a vertical axis, the former being both older and more common.[16]

Horizontal axis

Horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWT) have the main rotor shaft and electrical generator at the top of a tower, and must be pointed into the wind. Small turbines are pointed by a simple wind vane, while large turbines generally use a wind sensor coupled with a servo motor. Most have a gearbox, which turns the slow rotation of the blades into a quicker rotation that is more suitable to drive an electrical generator.[17]

Since a tower produces turbulence behind it, the turbine is usually positioned upwind of its supporting tower. Turbine blades are made stiff to prevent the blades from being pushed into the tower by high winds. Additionally, the blades are placed a considerable distance in front of the tower and are sometimes tilted forward into the wind a small amount.

Downwind machines have been built, despite the problem of turbulence (mast wake), because they don't need an additional mechanism for keeping them in line with the wind, and because in high winds the blades can be allowed to bend which reduces their swept area and thus their wind resistance. Since cyclical (that is repetitive) turbulence may lead to fatigue failures, most HAWTs are of upwind design.

Turbines used in wind farms for commercial production of electric power are usually three-bladed and pointed into the wind by computer-controlled motors. These have high tip speeds of over 320 km/h (200 mph), high efficiency, and low torque ripple, which contribute to good reliability. The blades are usually colored white for daytime visibility by aircraft and range in length from 20 to 40 meters (66 to 131 ft) or more. The tubular steel towers range from 60 to 90 meters (200 to 300 ft) tall. The blades rotate at 10 to 22 revolutions per minute. At 22 rotations per minute the tip speed exceeds 90 meters per second (300 ft/s).[18][19] A gear box is commonly used for stepping up the speed of the generator, although designs may also use direct drive of an annular generator. Some models operate at constant speed, but more energy can be collected by variable-speed turbines which use a solid-state power converter to interface to the transmission system. All turbines are equipped with protective features to avoid damage at high wind speeds, by feathering the blades into the wind which ceases their rotation, supplemented by brakes.

Vertical axis design

Vertical-axis wind turbines (or VAWTs) have the main rotor shaft arranged vertically. One advantage of this arrangement is that the turbine does not need to be pointed into the wind to be effective, which is an advantage on a site where the wind direction is highly variable. It is also an advantage when the turbine is integrated into a building because it is inherently less steerable. Also, the generator and gearbox can be placed near the ground, using a direct drive from the rotor assembly to the ground-based gearbox, improving accessibility for maintenance.

The key disadvantages include the relatively low rotational speed with the consequential higher torque and hence higher cost of the drive train, the inherently lower power coefficient, the 360 degree rotation of the aerofoil within the wind flow during each cycle and hence the highly dynamic loading on the blade, the pulsating torque generated by some rotor designs on the drive train, and the difficulty of modelling the wind flow accurately and hence the challenges of analysing and designing the rotor prior to fabricating a prototype.[20]

When a turbine is mounted on a rooftop the building generally redirects wind over the roof and this can double the wind speed at the turbine. If the height of a rooftop mounted turbine tower is approximately 50% of the building height it is near the optimum for maximum wind energy and minimum wind turbulence. Wind speeds within the built environment are generally much lower than at exposed rural sites,[21][22] noise may be a concern and an existing structure may not adequately resist the additional stress.

Subtypes of the vertical axis design include:

- Darrieus wind turbine

- "Eggbeater" turbines, or Darrieus turbines, were named after the French inventor, Georges Darrieus.[23] They have good efficiency, but produce large torque ripple and cyclical stress on the tower, which contributes to poor reliability. They also generally require some external power source, or an additional Savonius rotor to start turning, because the starting torque is very low. The torque ripple is reduced by using three or more blades which results in greater solidity of the rotor. Solidity is measured by blade area divided by the rotor area. Newer Darrieus type turbines are not held up by guy-wires but have an external superstructure connected to the top bearing.[24]

- Giromill

- A subtype of Darrieus turbine with straight, as opposed to curved, blades. The cycloturbine variety has variable pitch to reduce the torque pulsation and is self-starting.[25] The advantages of variable pitch are: high starting torque; a wide, relatively flat torque curve; a higher coefficient of performance; more efficient operation in turbulent winds; and a lower blade speed ratio which lowers blade bending stresses. Straight, V, or curved blades may be used.[26]

- Savonius wind turbine

- These are drag-type devices with two (or more) scoops that are used in anemometers, Flettner vents (commonly seen on bus and van roofs), and in some high-reliability low-efficiency power turbines. They are always self-starting if there are at least three scoops.

- Twisted Savonius

- Twisted Savonius is a modified savonius, with long helical scoops to provide smooth torque. This is often used as a rooftop windturbine and has even been adapted for ships.[27]

Another type of vertical axis is the Parallel turbine, which is similar to the crossflow fan or centrifugal fan. It uses the ground effect. Vertical axis turbines of this type have been tried for many years: a unit producing 10 kW was built by Israeli wind pioneer Bruce Brill in the 1980s.[28][unreliable source?]

Design and construction

Wind turbines are designed to exploit the wind energy that exists at a location. Aerodynamic modelling is used to determine the optimum tower height, control systems, number of blades and blade shape.

Wind turbines convert wind energy to electricity for distribution. Conventional horizontal axis turbines can be divided into three components:

- The rotor component, which is approximately 20% of the wind turbine cost, includes the blades for converting wind energy to low speed rotational energy.

- The generator component, which is approximately 34% of the wind turbine cost, includes the electrical generator,[29][30] the control electronics, and most likely a gearbox (e.g. planetary gearbox),[31] adjustable-speed drive[32] or continuously variable transmission[33] component for converting the low speed incoming rotation to high speed rotation suitable for generating electricity.

- The structural support component, which is approximately 15% of the wind turbine cost, includes the tower and rotor yaw mechanism.[34]

A 1.5 MW wind turbine of a type frequently seen in the United States has a tower 80 meters (260 ft) high. The rotor assembly (blades and hub) weighs 22,000 kilograms (48,000 lb). The nacelle, which contains the generator component, weighs 52,000 kilograms (115,000 lb). The concrete base for the tower is constructed using 26,000 kilograms (58,000 lb) of reinforcing steel and contains 190 cubic meters (250 cu yd) of concrete. The base is 15 meters (50 ft) in diameter and 2.4 meters (8 ft) thick near the center.[35]

Among all renewable energy systems wind turbines have the highest effective intensity of power-harvesting surface[36] because turbine blades not only harvest wind power, but also concentrate it.[37][dubious – discuss]

Unconventional designs

One E-66 wind turbine at Windpark Holtriem, Germany, carries an observation deck, open for visitors. Another turbine of the same type, with an observation deck, is located in Swaffham, England. Airborne wind turbines have been investigated many times but have yet to produce significant energy. Conceptually, wind turbines may also be used in conjunction with a large vertical solar updraft tower to extract the energy due to air heated by the sun.

Wind turbines which utilise the Magnus effect have been developed.[38]

The ram air turbine is a specialist form of small turbine that is fitted to some aircraft. When deployed, the RAT is spun by the airstream going past the aircraft and can provide power for the most essential systems if there is a loss of all on–board electrical power.[citation needed]

Wind turbines on public display

A few localities have exploited the attention-getting nature of wind turbines by placing them on public display, either with visitor centers around their bases, or with viewing areas farther away.[39] The wind turbines are generally of conventional horizontal-axis, three-bladed design, and generate power to feed electrical grids, but they also serve the unconventional roles of technology demonstration, public relations, and education.

Small wind turbines

Small wind turbines may be used for a variety of applications including on- or off-grid residences, telecom towers, offshore platforms, rural schools and clinics, remote monitoring and other purposes that require energy where there is no electric grid, or where the grid is unstable. Small wind turbines may be as small as a fifty-watt generator for boat or caravan use. Hybrid solar and wind powered units are increasingly being used for traffic signage, particularly in rural locations, as they avoid the need to lay long cables from the nearest mains connection point.[40] The U.S. Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) defines small wind turbines as those smaller than or equal to 100 kilowatts.[41] Small units often have direct drive generators, direct current output, aeroelastic blades, lifetime bearings and use a vane to point into the wind.

Larger, more costly turbines generally have geared power trains, alternating current output, flaps and are actively pointed into the wind. Direct drive generators and aeroelastic blades for large wind turbines are being researched.

Wind turbine spacing

On most horizontal windturbine farms, a spacing of about 6-10 times the rotor diameter is often upheld. However, for large wind farms distances of about 15 rotor diameters should be more economically optimal, taking into account typical wind turbine and land costs. This conclusion has been reached by research[42] conducted by Charles Meneveau of the Johns Hopkins University,[43] and Johan Meyers of Leuven University in Belgium, based on computer simulations[44] that take into account the detailed interactions among wind turbines (wakes) as well as with the entire turbulent atmospheric boundary layer. Moreover, recent research by John Dabiri of Caltech suggests that vertical wind turbines may be placed much more closely together so long as an alternating pattern of rotation is created allowing blades of neighbouring turbines to move in the same direction as they approach one another.[45]

Health monitoring of wind turbines

Due to data transmission problems, health monitoring of wind turbines is usually performed using several accelerometers and strain gages attached to the nacelle to monitor the gearbox and equipments.[46] Recently, digital image correlation and stereophotogrammetry is used to measure dynamics of wind turbine blades. These methods usually measure displacement and strain to identify location of defects. Dynamic characteristics of non-rotating wind turbines have been measured using digital image correlation and photogrammetry.[47] Three dimensional point tracking has also been used to measure rotating dynamics of wind turbines.[48]

Records

- Largest capacity

- The Vestas V164 has a rated capacity of 8.0 MW,[49] has an overall height of 220 m (722 ft), a diameter of 164 m (538 ft), and is the world's largest-capacity wind turbine since its introduction in 2014. At least five companies are working on the development of a 10 MW turbine.

- Largest swept area

- The turbine with the largest swept area is the Samsung S7.0-171, with a diameter of 171 m, giving a total sweep of 22966 m2.

- Tallest

- Vestas V164 is the tallest wind turbine, standing in Østerild, Denmark, 220 meters tall, constructed in 2014.

- Highest tower

- Fuhrländer installed a 2.5MW turbine on a 160m lattice tower in 2003 (see Fuhrländer Wind Turbine Laasow)

- Largest vertical-axis

- Le Nordais wind farm in Cap-Chat, Quebec has a vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT) named Éole, which is the world's largest at 110 m.[50] It has a nameplate capacity of 3.8 MW.[51]

- Largest 2 bladed turbine

- Today's biggest 2 bladed turbine is build by Mingyang Wind Power in 2013. It is a SCD6.5MW offshore downwind turbine, designed by aerodyn Energiesysteme[52][53]

- Most southerly

- The turbines currently operating closest to the South Pole are three Enercon E-33 in Antarctica, powering New Zealand's Scott Base and the United States' McMurdo Station since December 2009[54][55] although a modified HR3 turbine from Northern Power Systems operated at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in 1997 and 1998.[56] In March 2010 CITEDEF designed, built and installed a wind turbine in Argentine Marambio Base.[57]

- Most productive

- Four turbines at Rønland wind farm in Denmark share the record for the most productive wind turbines, with each having generated 63.2 GWh by June 2010.[58]

- Highest-situated

- Since 2013 the world's highest-situated wind turbine is made by United Windpower China Guodian Corporation installed by the Longyuan Power and located in the Naqu country, Tibet (China) around 4,800 meters (15,700 ft) above sea level.[59][60] The site uses a 1500 kW wind turbine designed by aerodyn Energiesysteme.[61]

- Largest floating wind turbine

- The world's largest—and also the first operational deep-water large-capacity—floating wind turbine is the 2.3 MW Hywind currently operating 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) offshore in 220-meter-deep water, southwest of Karmøy, Norway. The turbine began operating in September 2009 and utilizes a Siemens 2.3 MW turbine.[62][63]

See also

External links

- Harvesting the Wind (45 lectures about wind turbines by professor Magdi Ragheb)

- Wind Projects

- Guided tour on wind energy

- U.S. Wind Turbine Manufacturing: Federal Support for an Emerging Industry Congressional Research Service

- Wind Energy Technology World Wind Energy Association

- Wind turbine simulation, National Geographic

- Airborne Wind Industry Association international

- The world's 10 biggest wind turbines

- The Tethys database seeks to gather, organize and make available information on potential environmental effects of offshore wind energy development

Further reading

- Tony Burton, David Sharpe, Nick Jenkins, Ervin Bossanyi: Wind Energy Handbook, John Wiley & Sons, 2nd edition (2011), ISBN 978-0-470-69975-1

- Darrell, Dodge, Early History Through 1875, TeloNet Web Development, Copyright 1996–2001

- Robert Gasch, Jochen Twele (ed.), Wind power plants. Fundamentals, design, construction and operation, Springer 2012 ISBN 978-3-642-22937-4.

- Erich Hau, Wind turbines: fundamentals, technologies, application, economics Springer, 2013 ISBN 978-3-642-27150-2 (preview on Google Books)

- Siegfried Heier, Grid integration of wind energy conversion systems John Wiley & Sons, 3rd edition (2014), ISBN 978-1-119-96294-6

- Peter Jamieson, Innovation in Wind Turbine Design. Wiley & Sons 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-69981-2

- David Spera (ed,) Wind Turbine Technology: Fundamental Concepts in Wind Turbine Engineering, Second Edition (2009), ASME Press, ISBN #: 9780791802601

- Alois Schaffarczyk (ed.), Understanding wind power technology, John Wiley & Sons, (2014), ISBN 978-1-118-64751-6

- Hermann-Josef Wagner, Jyotirmay Mathur, Introduction to wind energy systems. Basics, technology and operation. Springer (2013), ISBN 978-3-642-32975-3

- Ersen Erdem, Wind Turbine Industrial Applications

References

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (January 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

- ^ "Part 1 — Early History Through 1875". Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ A.G. Drachmann, "Heron's Windmill", Centaurus, 7 (1961), pp. 145–151

- ^ Dietrich Lohrmann, "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 77, Issue 1 (1995), pp. 1–30 (10f.)

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Donald Routledge Hill (1986). Islamic Technology: An illustrated history, p. 54. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42239-6.

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, May 1991, p. 64-69. (cf. Donald Routledge Hill, Mechanical Engineering)

- ^ a b Morthorst, Poul Erik; Redlinger, Robert Y.; Andersen, Per (2002). Wind energy in the 21st century: economics, policy, technology and the changing electricity industry. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave/UNEP. ISBN 0-333-79248-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Price, Trevor J. (2004). "Blyth, James (1839–1906)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/100957. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ A Wind Energy Pioneer: Charles F. Brush. Danish Wind Industry Association. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ Quirky old-style contraptions make water from wind on the mesas of West Texas[dead link]

- ^ Alan Wyatt: Electric Power: Challenges and Choices. Book Press Ltd., Toronto 1986, ISBN 0-920650-00-7

- ^ Anon. "Costa Head Experimental Wind Turbine". Orkney Sustainable Energy Website. Orkney Sustainable Energy Ltd. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ "NREL: Dynamic Maps, GIS Data, and Analysis Tools – Wind Maps". Nrel.gov. 2013-09-03. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ IEC Wind Turbine Classes June 7, 2006

- ^ "The Physics of Wind Turbines Kira Grogg Carleton College, 2005, p.8" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Sanne Wittrup. "11 years of wind data shows surprising production decrease" (in Danish) Ingeniøren, 1 November 2013. Accessed: 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Wind Energy Basics". American Wind Energy Association. Archived from the original on 2010-09-23. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Products & Services". Gepower.com. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "Technical Specs of Common Wind Turbine Models". Aweo.org.

- ^ http://www.awsopenwind.org/downloads/documentation/ModelingUncertaintyPublic.pdf

- ^ Hugh Piggott (2007-01-06). "Windspeed in the city – reality versus the DTI database". Scoraigwind.com. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ http://www.urbanwind.net/pdf/technological_analysis.pdf

- ^ "Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines". Symscape. 2008-07-07. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Exploit Nature-Renewable Energy Technologies by Gurmit Singh, Aditya Books, pp 378

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Experimental Mechanics, Volume 18, Number 1 – SpringerLink" (PDF). Springerlink.com. 1978-01-01. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Rob Varnon. Derecktor converting boat into hybrid passenger ferry, Connecticut Post website, December 2, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Modular wind energy device – Brill, Bruce I". Freepatentsonline.com. 2002-11-19. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Navid Goudarzi (June 2013). "A Review on the Development of the Wind Turbine Generators across the World". International Journal of Dynamics and Control. 1 (2). Springer: 192–202. doi:10.1007/s40435-013-0016-y.

- ^ Navid Goudarzi, Weidong Zhu (November 2012). "A Review of the Development of Wind Turbine Generators Across the World". ASME 2012 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. 4 - Paper No: IMECE2012-88615. ASME: pp. 1257–1265.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Template:Html name. "ZF Friedrichshafen AG". Hansentransmissions.com. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "– de beste bron van informatie over djtreal. Deze website is te koop!". Djtreal.com. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ John Gardner, Nathaniel Haro and Todd Haynes (October 2011). "Active Drivetrain Control to Improve Energy Capture of Wind Turbines" (PDF). Boise State University. Retrieved 28 February 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ ""Wind Turbine Design Cost and Scaling Model", Technical Report NREL/TP-500-40566, December, 2006, page 35, 36" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ See Erich Hau: Windkraftanlagen: Grundlagen, Technik, Einsatz, Wirtschaftlichkeit. Berlin/ Heidelberg 2008, pp. 621. (German). (For the english Edition see Erich Hau, Wind Turbines: Fundamentals, Technologies, Application, Economics, Springer 2005)

- ^ "Innovation in Wind Turbine Design" (2011), Peter Jamieson

- ^ "Spiral Magnus|MECARO|Introducuction to Magnus". Mecaro.jp. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Young, Kathryn (2007-08-03). "Canada wind farms blow away turbine tourists". Edmonton Journal. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Anon. "Solar & Wind Powered Sign Lighting". Energy Development Cooperative Ltd. Energy Development Cooperative Ltd. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Small Wind, U.S. Department of Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory website

- ^ J. Meyers and C. Meneveau, "Optimal turbine spacing in fully developed wind farm boundary layers" (2012), Wind Energy 15, 305-317 doi:10.1002/we.469

- ^ January 18, 2011Print version (2011-01-18). "Optimal spacing for wind turbines". Gazette.jhu.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "M. Calaf, C. Meneveau and J. Meyers, "Large Eddy Simulation study of fully developed wind-turbine array boundary layers" (2010), Phys. Fluids 22, 015110". Link.aip.org. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Dabiri, J. Potential order-of-magnitude enhancement of wind farm power density via counter-rotating vertical-axis wind turbine arrays (2011), J. Renewable Sustainable Energy 3, 043104

- ^ End of Warranty Inspection,Retrieved 11/03/2014

- ^ Using Stereophotogrammetry to Predict Dynamic Strain on A Wind Turbine Rotor

- ^ Using Stereophotogrammetry to Measure Vibrations of a Rotating Wind Turbine

- ^ Wittrup, Sanne. "Power from Vestas' giant turbine" (in Danish. English translation ). Ingeniøren, 28 January 2014. Accessed: 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Visits : Big wind turbine". Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "Wind Energy Power Plants in Canada – other provinces". 2010-06-05. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ http://www.windpoweroffshore.com/article/1207686/close---aerodyns-6mw-offshore-turbine-design

- ^ http://www.windpowermonthly.com/article/1188373/ming-yang-install-65mw-offshore-turbine

- ^ "Antarctica New Zealand". Antarcticanz.govt.nz. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "New Zealand Wind Energy Association". Windenergy.org.nz. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Bill Spindler, The first Pole wind turbine.

- ^ GENERADOR DE ENERGÍA EÓLICA EN LA ANTÁRTIDA[dead link]

- ^ "Surpassing Matilda: record-breaking Danish wind turbines". Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ http://www.windpowermonthly.com/article/1142093/longyuan-builds-tibets-first-wind-farm

- ^ http://www.renewable-energy-technology.net/wind-energy-news/china-firm-builds-world%E2%80%99s-highest-wind-farm-tibet

- ^ http://www.eaton.com/Eaton/OurCompany/SuccessStories/Energy/GuodianUnitedPowerTechnologyCompany/index.htm

- ^ Patel, Prachi (2009-06-22). "Floating Wind Turbines to Be Tested". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

will test how the 2.3-megawatt turbine holds up in 220-meter-deep water.

- ^ Madslien, Jorn (8 September 2009). "Floating challenge for offshore wind turbine". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

world's first full-scale floating wind turbine