Ornithology

Ornithology (from Greek: ορνις, ornis, "bird"; and λόγος, logos, "knowledge") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of birds. Several aspects of the study of ornithology differ from closely related disciplines, possibly due to the high visibility and the aesthetic appeal of birds. Most marked among these is the extent of field studies undertaken by amateur volunteers working within the parameters of strict scientific methodology.

History

Early ornithology

Birds have interested humans since very early times, and stone age drawings of birds are possibly the oldest indications. Birds were perhaps an important food source for humans, and bones of as many as 80 species have been found in excavations of early settlements.[1]

Cultures in all parts of the world have rich vocabularies related to birds and their lives.[2] Traditional bird names are often onomatopoeic and many of these continue to be in use.[3] Traditional knowledge continues to be of importance especially due to their relevance in conservation.[4] Most of this information is passed on through oral traditions (see ethno-ornithology).[5][6]

The hunting of birds would have required considerable knowledge of their habits. Poultry farming and falconry were practised from early times in many parts of the world. Artificial incubation of poultry was practised in China (246 BC) and Egypt (at least 400 BC).[7] The Egyptians also showed a great deal of knowledge of birds through their use of bird symbols in hieroglyphs, many of which, though stylized, are still recognizable.

Some of the early written records are of ornithological interest in that they may provide information on past distributions of species. For instance Xenophon records the abundance of the Ostrich in Assyria (Anabasis, i. 5). Today the species is restricted to Africa. The Vedas (1500-800 BC) mention the habit of brood parasitism in the Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopacea).[8] The early art of China, Japan, Persia and India also shows a number of species of birds, some of them illustrated with great accuracy. David Lack wrote in his Review of Fine Bird Books, 1700-1900 (reprinted in Enjoying Ornithology, 1965):

It must be remembered that, while [John] Gould himself was a skilled craftsman, many of the books that bear his name were illustrated by others, including H. C. Richter, Edward Lear and Joseph Wolf. Indeed, some would regard the last-named as the greatest bird illustrator, particularly in his birds of prey, which combine accuracy with power. One must, I think, qualify this statement by 'of the western world', because the paintings from India and China surpass anything that the West has yet produced, and only these, perhaps, come in the category of great art.

Aristotle in 350 BC in his Historia Animalium[9] noted the habit of bird migration, moulting, egg laying and life spans. However, he also introduced several incorrect concepts, and although he noted that cranes travelled from the steppes of Scythia to the marshes at the headwaters of the Nile, he attributed the disappearance of swallows in winter to hibernation. This belief became so well established that the eminent nineteenth-century American ornithologist, Dr. Elliott Coues, listed in 1878 the titles of no less than 182 papers dealing with the hibernation of swallows.[10] The breeding places of Barnacle geese were unknown and their origins were explained by folk beliefs based on their transformation from goose barnacles. This idea was prevalent from around the 11th century and was noted by Bishop Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) in Topographia Hiberniae (1187).[11]

The origins of falconry have been traced to Mesopotamia and the earliest record comes from the reign of Sargon II (722–705 BC), however it appears to have made its entry to Europe only after AD 400, brought in from the East after invasions by the Huns and Allans. Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor of Hohenstaufen (1194 – 1250) learnt about Arabian falconry during wars in the region and he obtained an Arabic treatise on falconry by Moamyn. This was translated into Latin and led him to conduct experiments on birds. By sealing the eyes of vultures and placing food nearby, he concluded that they can only find food by sight, and not by smell. He also found methods to keep and train falcons. The studies he undertook were published in 1240 after nearly 30 years of experience in falconry as De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (The Art of Hunting with Birds).[12]

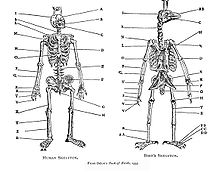

Early German and French scholars also studied the works of Aristotle and conducted new research on birds. The major works included those by Guillaume Rondelet describing his personal observations in the Mediterranean and Pierre Belon who described the fish and birds that he had met with in France and the Levant. Belon's Book of Birds (1555) is a folio volume with descriptions of some two hundred species. His comparison of the skeleton of humans and birds is considered remarkable.[13] Konrad Gesner wrote the Vogelbuch and Icones avium omnium around 1557. Like Gesner, Ulisse Aldrovandi, an encyclopedic naturalist began a 14-volume natural history with three volumes on birds, entitled ornithologiae hoc est de avibus historiae libri XII which was published from 1599 to 1603. Aldrovandi showed great interest in plants and animals and his works include 3000 drawings of fruits, flowers, plants and animals and they were documented in 363 volumes. His Ornithology alone covers 2000 pages and in it he covers, for instance, chickens and poultry techniques extensively.[14][15]William Turner's Historia Avium ("History of Birds"), published at Cologne in 1544, was another early ornithological work. He notes that the kite in cities of England would snatch the meat out of the hands of children. In his day the Osprey was better known to Englishmen than they liked, for it emptied their fishponds; anglers used to mix their bait with its fat. Turner's work was written in a very different tone, quite unlike the writings of Gilbert White, such as The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, that were made in a more tranquil era.[13][16] In the 17th century Francis Willughby (1635-1672) and John Ray (1627-1705) came up with the first major system of bird classification that was based on function and morphology rather than on form or behavior. Willughby's Ornithologiae libri tres (1676) completed by John Ray is considered to mark the beginning of scientific ornithology. Ray also worked on Ornithologia which was then published posthumously in 1713 as Synopsis methodica avium et piscium.[17] The earliest list of British birds, Pinax Rerum Naturalium Britannicarum was written by Christopher Merrett in 1667, however it was not considered of value by many including John Ray.[18]

Several ornithological works were also started in the late 1700s in France through the works of Mathurin Jacques Brisson (1723-1806) and Comte de Buffon (1707-1788). Brisson produced a six-volume work Ornithologie in 1760 and Buffon's include nine volumes on birds Histoire naturelle des oiseaux (1770-1785) as volumes 16 to 24 of his work on science Histoire naturelle générale et particulière (1749-1804). Coenraad Jacob Temminck (1778 - 1858) sponsored François Le Vaillant [1753-1824] to collect in Africa and this resulted in Le Vaillant's six-volume Histoire naturelle des oiseaux d'Afrique (1796-1808). Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot (1748-1831) spent ten years studying North American birds and wrote the Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de l'Amerique septentrionale (1807-1808?). Vieillot pioneered in the use of life-histories and habits in classification.[19]

Scientific ornithology

It was not until the Victorian era—with the emergence of the gun, the concept of natural history, and the collection of natural objects such as bird eggs and skins—that ornithology emerged as a specialized science.[20] This specialization led to the formation in Britain of the British Ornithologists' Union in 1858. In 1859 the members founded its journal The Ibis. The sudden spurt in ornithology was also due in part to colonization. A hundred years later, in 1959, R. E. Moreau noted that ornithology in this period was preoccupied with the geographical distributions of various species of birds.[21]

No doubt the preoccupation with widely extended geographical ornithology, was fostered by the immensity of the areas over which British rule or influence stretched during the 19th century and for some time afterwards.[22]

The bird collectors of the Victorian era observed the variations in bird forms and habits across geographic regions, noting local specialization and variation in widespread species. The collections of museums and private collectors grew with contributions from various parts of the world. The naming of species with binomials and the organization of birds into groups based on their similarities became the main work of museum specialists. The variations in widespread birds across geographical region caused the introduction of trinomial names.

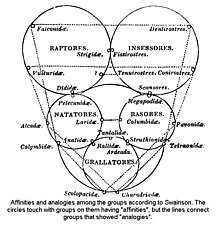

The search for patterns in the variations of birds was attempted by many. Early ornithologists like William Swainson followed the Quinarian system and this was replaced by more complex "maps" of affinities in works by Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alfred Russell Wallace.[23] The Galapagos finches were especially influential in the development of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. His contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace also noted these variations and the geographical separations between different forms leading to the study of biogeography. Wallace was influenced by the work of Philip Lutley Sclater on the distribution patterns of birds.[24]

For Darwin, the problem was how species arose from a common ancestor, but he did not attempt to find rules for delineation of species. The species problem, was tackled by the ornithologist Ernst Mayr. Mayr was able to demonstrate that geographical isolation and the accumulation of genetic differences led to the splitting of species.[25]

While the ideas of species, their identities and geographic distribution began to be developed, the focus gradually shifted to the study of the living bird, or studies of the life history of birds.[21] The study of birds in their habitats was particularly advanced in Germany and as early as 1903, had established bird ringing stations. By the 1920s the Journal für Ornithologie included many papers on the behavior, ecology, anatomy and physiology, many written by Erwin Stresemann. Ornithology in the United States was also restricted to the study of variations, species and geographic distributions, until it was influenced by Stresemann's student Ernst Mayr.[26] In Britain, some of the earliest ornithological works that used the word ecology appeared in 1915.[27] The Ibis however resisted the introduction of these new methods of study and it was not until 1943 that any paper on ecology appeared.[21] The work of David Lack on population ecology was pioneering. The new rigour and quantitative approaches being used ornithology were not acceptable to many. For instance, Claud Ticehurst wrote:

Sometimes it seems that elaborate plans and statistics are made to prove what is commonplace knowledge to the mere collector, such as that hunting parties often travel more or less in circles.[21]

David Lack's studies on population ecology included the mechanism involved in the regulation of population including the evolution of optimal clutch sizes. He concluded that population was regulated primarily by density-dependent controls, and also suggested that natural selection leads to life history traits that maximize the fitness of individuals. Others like Wynne-Edwards interpreted population regulation as a mechanism that aided the "species". This led to widespread debate on what constituted the "unit of selection".[25] Lack also pioneered the use of many new tools for research including the idea of using radar to study bird migration.

Birds were also widely used in studies of the niche hypothesis and Gause's competitive exclusion principle. Work on resource partitioning and the structuring of bird communities through competition were made by Robert MacArthur. Patterns of biodiversity also became a topic interest. Work on the relationship of the number of species to area and its application in the study of Island biogeography was pioneered by E. O. Wilson and Robert MacArthur.[25] These studies led to the development of the discipline of landscape ecology.

John Hurrell Crook studied the behaviour of weaverbirds and demonstrated the links between ecological conditions, behaviour and social systems.[25][28] Principles from economics were introduced into the study of biology by J. L. Brown. This led to the study of behaviour using cost-benefit analyses.[29] The rising interest in sociobiology also led to a spurt of bird studies in this area.[25][30]

The study of imprinting behaviour in ducks and geese by Konrad Lorenz and the studies of instinct in Herring Gulls by Nicolaas Tinbergen, led to the establishment of the field of ethology. The study of learning became particularly of interest and the study of bird song has been a model for studies in neuroethology. The role of hormones and physiology in the control of behaviour has also been aided by bird models. These have helped in the study of circadian and seasonal cycles. Studies on migration have attempted to answer questions on the evolution of migration, orientation and navigation.[25]

The growth of genetics and the rise of molecular biology saw the new gene-centered view of evolution. Studies on kinship and altruism, such as helpers, became of particular interest. The idea of inclusive fitness was used to interpret observations on behaviour and life-history and birds were widely used models for testing hypotheses based on theories postulated by W. D. Hamilton and others.[25]

The new tools of molecular-biology also led to new approaches to the study of bird systematics. The use of techniques such as DNA-DNA hybridization to study evolutionary relationships was pioneered by Charles Sibley and Jon Edward Ahlquist resulting in what is called the Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy. These early techniques have been replaced by newer techniques based on mitochondrial DNA sequences and molecular phylogenetics approaches that make use of computational procedures for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction to infer the evolutionary relationships of birds.[31][32] Molecular techniques are also widely used in studies of avian population biology and ecology.[33]

Popular ornithology

The rise of field guides for the identification of birds was a major innovation. The early guides were large and cumbersome and were mainly focussed on identifying specimens in the hand. The earliest of the new generation of field guides was prepared by Florence Merriam, sister of Clinton Hart Merriam, the mammalogist. This was published in 1887 in a series Hints to Audubon Workers:Fifty Birds and How to Know Them in Grinnell's Audubon Magazine.[26] These were followed by new field guides including classics by R. T. Peterson.[34]

The interest in bird study grew in popularity in many parts of the world and it was realized that there was a possibility for amateurs to contribute to professional biology. As early as 1916, Julian Huxley wrote a two part article in the Auk, noting the tensions between amateurs and professionals and suggesting the possibility that the "vast army of bird-lovers and bird-watchers could begin providing the data scientists needed to address the fundamental problems of biology."[35][36]

The formation of popular organizations with large member bases grew in many countries, notably the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in Britain and the Audubon Society in the US. The Audubon Society started in 1885. Both these organization were started with the primary objective of conservation. The RSPB, born in 1889, grew from a small group of women in Croydon who met regularly and called themselves the Fur, Fin and Feather Folk and who took a pledge 'to refrain from wearing the feathers of any birds not killed for the purpose of food, the Ostrich only exempted.' The organization initially did not allow men as members, avenging a policy of the British Ornithologists' Union to keep out women.[20] Unlike the RSPB, which was primarily conservation oriented, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) was started in 1933 with the aim of advancing ornithological study. Members were often involved in collaborative ornithological projects. These projects have resulted in atlases which detail the distribution of bird species across Britain.[37] In the United States, the Breeding Bird Surveys, conducted by the US Geological Survey have also produced atlases with information on breeding densities and changes in the density and distribution over time. Other volunteer collaborative ornithology projects were established in many other parts of the world.[38]

Ornithological techniques

The tools and techniques of ornithology are varied and new inventions and approaches are quickly incorporated. The techniques may be broadly dealt under the categories of those that are applicable to specimens and those that are used in the field, however the classification is imperfect as many of the newer non-destructive sampling and analysis techniques are applicable in both the laboratory and field.

Specimen techniques

The early approaches to bird study involved the collection of eggs. While collecting became a pastime for many amateurs, the labels associated with these egg collections made them unreliable for the serious study of bird breeding. In order to preserve eggs, a tiny hole was pierced and the contents were extracted out. This technique became standard with the invention of the blow drill around 1830.[20] Historic museum collections have however been of value in determining the effect of modern pesticides such as DDT.[39][40] Museum bird collections continue to act as a resource for taxonomic studies.[41]

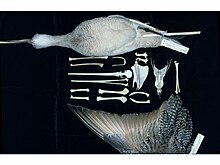

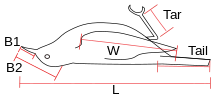

The use of bird skins for documenting species has been central to systematic ornithology. Bird skins are prepared by retaining the key bones of the wings, leg and skull along with the skin and feathers. They were treated with arsenic to prevent fungal and insect (mostly Dermestidae) attack. Arsenic being toxic was later replaced by borax. Sportsmen became familiar with these skinning techniques and started sending in their skins to museums, some of them from far away locations. This led to the formation of huge collections of bird skins in Museums in Europe and North America. Many private collections were also held. These became references for comparison of species and the ornithologists at these museums were able to document species from locations that they never visited. Morphometrics of these skins, particularly the lengths of the tarsus, bill, tail and wing became important in bird systematics. These historic skin collections have also been utilized in more recent studies on molecular phylogenetics by the extraction of ancient DNA. The importance of type specimens in the description of species make skin collections a vital resource for systematic ornithology. However, with the rise of molecular techniques, it has now become possible to establish the species status of rare discoveries such as the Bulo Burti Boubou Laniarius liberatus and the Bugun Liocichla Liocichla bugunorum using blood, DNA and feather samples as the holotype material.

Other approaches to the preservation of bird material have included the storage of specimens in spirit. Such wet-specimens have special value in physiological and anatomical studies. They also provide better quality of DNA for molecular studies.[42] Freeze drying of specimens has also been attempted in more recent times. While the technique has advantages in that it preserves stomach contents and anatomy, it may have the same problems as dry skins in that shrinkage can occur leading to errors in morphometrics.[43] [44]

Field techniques

The study of birds in the field was helped enormously by the advent of optics. Photography and particularly digital photography has made it possible now to document birds in the field with great accuracy. The new optics allows observers to detect minute morphological differences that were once detectable only by examination of the specimen in the hand.[45]

The capture of birds however provides certain kinds of information that are critical to life-history studies. The range of capture techniques include the use of bird liming for perching birds, mist nets for woodland birds, cannon netting for open area flocking birds, the Bal chattri for raptors,[46] decoys and funnel traps for open water ducks.[47]

The bird in the hand may be examined for morphometrics including weight. The examination of feather moult and skull ossification give indicators of age and health. Sex can be determined by examination of anatomy in some sexually non-dimorphic species. The extraction of blood samples and their later study make it possible to study the physiological conditions of the bird. DNA sequences can be used to identify the geographical origins of migrant populations using genetic markers and also to study kinship in studies on breeding biology. Blood samples can also be used for the study of pathogens and arthropod borne viruses. Ectoparasites, collected from specimens are used in studies of coevolution and the study of zoonoses.[48] In many of the warbler species, morphometrics and the examination of the wing-point are also important in establshing their identity.

Captured birds may also be marked for future recognition. Marking techniques include the use of bird ringing, colour dyes, wing tags. The use of mark and recapture techniques make it possible to estimate bird populations and the study of age structure in the populations. The traditional application of marking techniques is however in the study of migration. In more recent times the use of satellite transmitters makes it possible to study bird migration in real-time. Visible marks such as coloured rings and dyes enable the identification of individual birds and are widely used in studies of behaviour.[49]

Techniques for population density estimation include the point count, transect and territory mapping. Data is gathered in the field using well defined protocols and the results may be used to estimate bird diversity and population.[50]

Laboratory techniques

Many aspects of bird biology are difficult to study in the field. These include the study of behaviour and physiological changes that require a long duration of access to the bird. In some cases field study can be augmented by laboratory studies of samples obtained in the field, for instance of blood or feather. For instance, the variation in the ratios of stable hydrogen isotopes across latitudes makes it possible to roughly establish the origins of migrant birds by mass spectroscopic analysis of the hydrogen isotopes in feathers.[51] The use of this technique augments other migration study techniques such as ringing.[52]

Studies in bird behaviour include the use of tamed and trained birds. Studies on bird intelligence have been primarily based on laboratory studies. Field studies make use of a wide range of techniques including the use of dummy owls to elicit mobbing behaviour, dummy males to elicit territorial behaviour and thereby to establish the boundaries of bird territories and the use of call playback.[53]

Studies of bird migration including aspects of navigation, orientation and physiology are often studied using captive birds in special cages that record their activities. [54]

Collaborative studies

With the widespread interest in birds, it has been possible to use a large number of people to work on collaborative ornithological projects. These citizen science projects include nation-wide projects such as the Christmas Bird Count,[55] Backyard Bird Count,[56] the North American Breeding Bird Survey, the Canadian EPOQ[57] or regional projects such as the Asian Waterfowl Census. These projects help to identify distributions of birds, their population densities and changes over time, arrival and departure dates of migration, breeding seasonality and even population genetics.[58] Studies of migration using bird ringing or colour marking often involve the cooperation of people and organizations in different countries.[59]

Applied ornithology

Ornithology has many applications in human life and studies aimed at these areas are called applied or economic ornithology.

The role of some species of birds as pests has been well known, particularly in agriculture. Granivorous birds such as the Queleas in Africa have been among the most numerous birds in the world and foraging flocks can cause devastation.[60][61] Large flocks of pigeons and starlings in cities have also been considered a nuisance and ornithologists have sought a variety of techniques to solve these problems. Birds have also been of medical importance and their role as carriers of diseases such as Japanese Encephalitis, West Nile Virus and H5N1 has been significant.[62][63] Bird strikes and the damage they cause in aviation are also of particular importance, due in part to the fatal consequences and the level of economic impact that they have. The airline industry has estimated worldwide dammages of US $ 1.2 billion each year.[64]

Many species of birds have been driven to extinction by human activities. Bird conservation requires specialized knowledge in aspects of biology, ecology and may require the use of very location specific approaches. Ornithologists contribute to conservation biology by studying the ecology of birds in the wild and identifying the key threats and ways of enhancing the survival of species.[65] In some cases this may involve the capture and raising in captivity of critically endangered species. Such ex-situ conservation measures may be followed by re-introduction of the species into the wild.[66]

See also

- List of ornithological societies

- List of ornithology journals

- List of famous ornithologists

- Bird observatory

- Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology

- The Institute for Bird Populations

References

- ^ Nadel, K. D., Ehud Weiss, Orit Simchoni, Alexander Tsatskin, Avinoam Danin, and Mordechai (2004) Stone Age hut in Israel yields world's oldest evidence of bedding. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 101(17):6821-6826 [1]

- ^ Hawaiian bird names Accessed December 2007

- ^ Gill, Frank & M. Wright (2006) Birds of the world: Recommended English Names. Princeton University Press. Online supplement

- ^ Mahawar, M. M. & D. P. Jaroli 2007. Traditional knowledge on zootherapeutic uses by the Saharia tribe of Rajasthan, India. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 3:25 Full text

- ^ Shapiro, M. Native bird names. Richmond Audubon Society. Accessed December 2007

- ^ Hohn, E.O. 1973. Mammal and bird names in the Indian languages of the Lake Athabasca area. Arctic 26; 163-171. PDF

- ^ Funk, E. M. and M. R. Irwin 1955. Hatching Operation and Management. John Wiley & sons.

- ^ Ali, S. (1979), Bird study in India : its history and its importance. ICCR, New Delhi. Azad Memorial Lectures.

- ^ Aristotle, Historia Animalium. Translated by D'Arcy Thompson

- ^ Lincoln, Frederick C., Steven R. Peterson, and John L. Zimmerman. 1998. Migration of birds. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. Circular 16. Jamestown, ND: Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. [2]

- ^ Payne, S. (1929). The Myth of the Barnacle Goose. Int. J. Psycho-Anal., 10:218-227.

- ^ Egerton, F. 2003. A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 8: Fredrick II of Hohenstaufen: Amateur Avian Ecologist and Behaviorist. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 84(1):40–44. PDF

- ^ a b Miall, L. C. 1911. History of Biology. Watts and Co. Scanned version

- ^ Aldrovandi on Chickens: The Ornithology of Ulisse Aldrovandi, vol. 2, Bk xiv, translated and edited by L. R. Lind, University of Oklahoma Press, 1963, pp. xxxvi, 447, illus. Review

- ^ Ornithologiae, 1599 (Scanned version from Strasbourg University digital library)

- ^ White, Gilbert (1887) [1789]. The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. London: Cassell & Company. p. pp. 38-39. OCLC 3423785.

{{cite book}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ White, Jeanne A. 1999 Ornithology Collections in the Libraries at Cornell University: A Descriptive Guide [3]

- ^ Albert J. Koinm 2000. Christopher Merret's Use of Experiment. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 54(1):23-32

- ^ Jeanne A. White, Hill Collection — 18th c. French authors & artists online

- ^ a b c Allen, David E. 1994. The naturalist in Britain: a social history. Princeton University Press.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Kristin (2004) The Ibis: Transformations in a Twentieth Century British Natural History Journal. Journal of the History of Biology 37: 515–555

- ^ Moreau, R. E. (1959) The Centenarian Ibis. The Ibis 101: 19–38

- ^ O’Hara, Robert J. 1988. Diagrammatic classifications of birds, 1819–1901: views of the natural system in 19th-century British ornithology. Pp. 2746–2759 in: Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici (H. Ouellet, ed.). Ottawa: National Museum of Natural Sciences. Full text

- ^ Sclater, P. L. 1858. On the general geographical distribution of the members of the class Aves. Journ. and Proc. Linn. Soc., London, 9: 150-145.

- ^ a b c d e f g Masakazu Konishi; Stephen T. Emlen; Robert E. Ricklefs; John C. Wingfield (1989) Contributions of Bird Studies to Biology. Science 246(4929):465-472.

- ^ a b Barrow, Mark V. (1998) A passion for birds: American ornithology after Audubon. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Alexander, H. G. (1915) A Practical Study of Bird Ecology. British Birds. Vol. VIII, No. 9

- ^ Crook, J. H. 1964. The evolution of social organization and visual communication in the weaver birds (Ploceinae). Behaviour Suppl. 10:1-178.

- ^ Brown, J. L. 1964. The evolution of diversity in avian territorial systems. Wilson Bull. 76: 160-169

- ^ The Auk 1981 98(2)

- ^ O'Hara, Robert J. 1991. Essay review of Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: A Study in Molecular Evolution by Charles G. Sibley and Jon E. Ahlquist. Auk, 108(4):990–994. Full text

- ^ Slack, K.E, Delsuc, F., Mclenachan, P.A., Arnason, U., and D. Penny. (2007). Resolving the root of the avian mitogenomic tree by breaking up long branches. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42:1-13. PDF

- ^ Michael D. Sorenson , and Robert B. Payne (2002) Molecular Genetic Perspectives on Avian Brood Parasitism. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42: 388-400 Full text

- ^ Tom Dunlap, "Tom Dunlap on Early Bird Guides," Environmental History January 2005 online (Accessed 24 Nov. 2007)

- ^ Huxley, J. 1916. Bird-watching and biological science. The Auk. 33(2):142-161 (part 1) [4]

- ^ Huxley, J. 1916. Bird-watching and biological science. The Auk. 33(3):256-270 (part 2) [5]

- ^ Bibby C.J.(2003) Fifty years of Bird Study: Capsule Field ornithology is alive and well, and in the future can contribute much more in Britain and elsewhere. Bird Study. 50(3):194-210(17) Full text

- ^ North American Breeding Bird Survey

- ^ Newton, I. 1979. Population ecology of raptors. T. & A. D. Poyser, Berkhamsted.

- ^ Green, Rhys E. & Jörn P. W. Scharlemann (2003) Egg and skin collections as a resource for long-term ecological studies. Bull. B.O.C. 123A:165–176 [6]

- ^ Winker, K. 2004. Natural history museums in a postbiodiversity era. Bioscience 54:455-459.

- ^ Livezey, Bradley C. (2003) Avian spirit collections: attitudes, importance and prospects. Bull. B. O. C. 123A:35-51 [7]

- ^ Winker, K. 1993. Specimen shrinkage in Tennessee warblers and Traill's flycatchers. J. Field Ornithol. 64(3):331-336 [8]

- ^ Bjordal, H. 1983. Effects of deep freezing, freeze-drying and skinning on body dimensions of House Sparrows (Passer domesticus). Cinclus 6:105-108.

- ^ Hayman, Peter, John Marchant & Tony Prater. 1986. Shorebirds: An Identification Guide to the Waders of the World. Croom Helm, London.

- ^ Berger D. D., Mueller, H C (1959) The Bal-Chatri: a trap for the birds of prey.Bird-Banding 30: 19-27.[9]

- ^ USGS, Techniques to capture Seaducks in the Chesapeake Bay and Restigouche River

- ^ Walther, B. A. & D. H. Clayton 1997 Dust-ruffling: A simple method for quantifying ectoparasite loads of live birds. J. Field Ornithol., 68(4):509-518 PDF

- ^ Marion, W. R., & J. D. Shamis. 1977. An annotated bibliography of bird marking techniques. Bird-Banding 48:42-61. PDF

- ^ Bibby C., Jones M., Marsden S., 1998: Expedition Field Techniques. - Bird Surveys. Expedition Advisory Centre, Royal Geographical Society, London. [10]

- ^ Hobson, K. A. Hobson, Steven Van Wilgenburg, Leonard I. Wassenaar, Helen Hands, William P. Johnson, Mike O'Meilia, and Philip Taylor (2006) Using Stable Hydrogen Isotope Analysis of Feathers to Delineate Origins of Harvested Sandhill Cranes in the Central Flyway of North America. Waterbirds 29(2):137-147 [11]

- ^ Berthold, P. Eberhard Gwinner, Edith Sonnenschein. (2003) Avian Migration. Springer.

- ^ Slater, P. J. B. (2003) Fifty years of bird song research: a case study in animal behaviour. Animal Behaviour 65:633–639 doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2051

- ^ Emlen, S. T. and Emlen, J. T. (1966). A technique for recording migratory orientation of captive birds. Auk 83, 361–367.

- ^ Wing, L. 1947. Christmas census summary 1900-1939. State College of Washington, Pullman. Mimeograph.

- ^ Great Backyard Bird Count

- ^ EPOQ

- ^ Project PigeonWatch

- ^ EURING Coordinated bird-ringing in Europe

- ^ Clive C.H. Elliott (2006) Bird population explosions in agroecosystems — the quelea, Quelea quelea, case history. Acta Zoologica Sinica. 52:554-560 [12]

- ^ Michael M. Jaegar, WIlliam A. Erickson 1980. Levels of bird damage to Sorghum in the Awash basin of Ethiopia nad the effects of the control of Quelea nesting colones. Proceedings of the 9th Vertebrate Pest conference. Full text

- ^ CDC Factsheet on Avian Influenza

- ^ Reed, K. D., Jennifer K. Meece, James S. Henkel, and Sanjay K. Shukla (2003) Birds, Migration and Emerging Zoonoses: West Nile Virus, Lyme Disease, Influenza A and Enteropathogens. Clin. Med. Res. 1(1):5-12 Full text

- ^ Allan, J., Orosz, A. 2001. The Costs of Birdstrikes to Commercial Aviation. Proceedings of Birdstrike 2001, Joint Meeting of Birdstrike Committee USA/Canada. Calgary, Alberta

- ^ BirdLife International. 2000. Threatened Birds of the World: The official source for birds on the IUCN Red List. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, and BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK.

- ^ Whitfort, Harriet L., Robert J. Young 2004. Trends in the captive breeding of threatened and endangered birds in British zoos, 1988-1997. Zoo Biology 23(1):85-89

External links

- Ornithologie (1773-1792) Francois Nicholas Martinet Digital Edition Smithsonian Digital Libraries

- List of oldest ornithological organisations in the world

- History of ornithology in North America

- History of ornithology in China

- Hill ornithology collections

- History of ornithology (in Italian)