Predicting the timing of peak oil: Difference between revisions

Added information about Azerbaijan oil production peak at 50.8 million tonnes in 2010 (45.6 Mt in 2011, 43.4 Mt in 2012) |

rewrite -- most information here is from 2010 or so |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Main|Peak oil}} |

|||

[[File:Estimates of Peak World Oil Production.jpg|thumb|36 Estimates of the year of peak world oil production (US EIA)]] |

[[File:Estimates of Peak World Oil Production.jpg|thumb|36 Estimates of the year of peak world oil production (US EIA)]] |

||

[[Peak oil]] is the point at which oil production, sometimes including [[unconventional oil]] sources, hits its maximum. '''Predicting the timing of peak oil''' involves estimation of future production from existing oil fields as well as future discoveries. Although [[Hubbert peak theory]] was proposed in the 1950s, it was not until the early 21st century that serious interest in a reliable estimate of future oil production arose. As of 2014, it is not widely questioned that oil production will be in decline after 2050. The effect of peak oil on the world economy remains controversial. |

|||

Various sources '''predicting the timing of [[peak oil]]''' include assertions that it would peak decades ago, that it has recently occurred, that it will occur shortly, or that a plateau of oil production will sustain supply for up to 100 years. Predictions have changed through the years as up-to-date information such as new reserve growth data became available, or predictions of an early peak turned out to be incorrect.<ref name=usgsreservegrowth> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://energy.cr.usgs.gov/oilgas/addoilgas/reserve.html |

|||

|title=Reserve Growth |

|||

|publisher=[[USGS]] |

|||

|author= |

|||

|date= |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

==Present range of predictions== |

|||

According to [[Matthew Simmons]], former Chairman of [[Simmons & Company International]] and author of ''Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy'', "...peaking is one of these fuzzy events that you only know clearly when you see it through a rear view mirror, and by then an alternate resolution is generally too late."<ref> |

|||

There is a general consensus between industry leaders and analysts that world oil production will peak between 2010 and 2030, with a significant chance that the peak will occur before 2020. Dates after 2030 are considered implausible.<ref name="madureira"/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Sorrell|first=Steve|coauthors=Miller, Richard; Bentley, Roger; Speirs, Jamie|title=Oil futures: A comparison of global supply forecasts|journal=Energy Policy|date=September 2010|volume=38|issue=9|pages=4990–5003|doi=10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.020}}</ref> Determining a more specific range is difficult due to the lack of certainty over the actual size of world oil reserves.<ref name="chapman">{{cite journal|last=Chapman|first=Ian|title=The end of Peak Oil? Why this topic is still relevant despite recent denials|journal=Energy Policy|date=January 2014|volume=64|pages=93–101|doi=10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.010}}</ref> Unconventional oil is not currently predicted to meet the expected shortfall even in a best-case scenario.<ref name="madureira">{{cite book|last=Madureira|first=Nuno Luis|title=Key Concepts in Energy|date=2014|publisher=Springer International Publishing|location=London|isbn=978-3-319-04977-9|pages=125-6|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-04978-6_6}}</ref> For unconventional oil to fill the gap without "potentially serious impacts on the global economy", oil production would have to remain stable after its peak, until 2035 at the earliest.<ref name="royal">{{cite journal|last=Miller|first=R. G.|coauthors=Sorrell, S. R.|title=The future of oil supply|journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences|date=2014|volume=372|issue=2006|pages=20130179–20130179|doi=10.1098/rsta.2013.0179|quote=[W]e estimate that around 11–15 mb per day of non-conventional liquids production could be achieved in the next 20 years . . . If crude oil production falls, then total liquids production seems likely to fall as well, leading to significant price increases and potentially serious impacts on the global economy.}}</ref> |

|||

{{cite conference |

|||

| first = Aleklett |

|||

| last = K. |

|||

| coauthors = Campbell C., Meyer J. |

|||

| title = Matthew Simmons Transcript |

|||

| booktitle = Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Oil Depletion, |

|||

| publisher = The Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas |

|||

| date = May 26–27, 2003 |

|||

| location = Paris, France |

|||

| url = http://www.peakoil.net/iwood2003/MatSim.html |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-05-24 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

== |

==Past predictions== |

||

[[File:Petroleum Consumption Enormous article in Tractor and Gas Engine Review vol 11 no 05 1918.png|thumb|"Petroleum consumption enormous", article in ''Tractor and Gas Engine Review'', 1918.]] |

[[File:Petroleum Consumption Enormous article in Tractor and Gas Engine Review vol 11 no 05 1918.png|thumb|"Petroleum consumption enormous", article in ''Tractor and Gas Engine Review'', 1918.]] |

||

[[File:Hubbert peak oil plot.svg|thumb|A [[logistic distribution]] shaped world oil production curve, peaking at 12.5 billion barrels per year about the year 2000, as originally proposed by [[M. King Hubbert]] in 1956]] |

[[File:Hubbert peak oil plot.svg|thumb|A [[logistic distribution]] shaped world oil production curve, peaking at 12.5 billion barrels per year about the year 2000, as originally proposed by [[M. King Hubbert]] in 1956]] |

||

The idea that human use of petroleum faces [[sustainability]] limits attracted practical concern at least as early as the 1910s, as did the related idea that the timing of those limits depends on the extraction technology. A correspondent named W.D. Hornaday, quoting oil industry executive [[Joseph S. Cullinan|J.S. Cullinan]], described the concerns in a 1918 article for ''Tractor and Gas Engine Review'' titled "Petroleum consumption enormous."<ref name="Hornaday_1918-05">{{Citation |last=Hornaday |first=W.D. |date=May 1918 |title=Petroleum consumption enormous |journal=Tractor and Gas Engine Review |volume=11 |issue=5 |page=72 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=B6DmAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA72#v=onepage&q&f=false |postscript=.}}</ref> The article said, "There has been considerable discussion of late as to the possible length of time that the petroleum supply of the United States and the world will hold out."<ref name="Hornaday_1918-05"/> The article quoted Cullinan as saying, "It is just possible, so far as the United States is concerned, that the development and the exhaustion of the supplies may occur within the course of one human life. It is certain that unless radical changes from present methods are applied promptly, all sources of supply within the range of known drilling methods will be exhausted during the life of your children and mine."<ref name="Hornaday_1918-05"/> It turned out that radical changes from 1910s drilling methods were, in fact, applied promptly, and thus, the predicted timeframe was premature; but the underlying concerns (that the vastness of consumption would lead to shortages soon enough to worry about, regardless of the exact decade) did not disappear. |

The idea that human use of petroleum faces [[sustainability]] limits attracted practical concern at least as early as the 1910s, as did the related idea that the timing of those limits depends on the extraction technology. A correspondent named W.D. Hornaday, quoting oil industry executive [[Joseph S. Cullinan|J.S. Cullinan]], described the concerns in a 1918 article for ''Tractor and Gas Engine Review'' titled "Petroleum consumption enormous."<ref name="Hornaday_1918-05">{{Citation |last=Hornaday |first=W.D. |date=May 1918 |title=Petroleum consumption enormous |journal=Tractor and Gas Engine Review |volume=11 |issue=5 |page=72 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=B6DmAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA72#v=onepage&q&f=false |postscript=.}}</ref> The article said, "There has been considerable discussion of late as to the possible length of time that the petroleum supply of the United States and the world will hold out."<ref name="Hornaday_1918-05"/> The article quoted Cullinan as saying, "It is just possible, so far as the United States is concerned, that the development and the exhaustion of the supplies may occur within the course of one human life. It is certain that unless radical changes from present methods are applied promptly, all sources of supply within the range of known drilling methods will be exhausted during the life of your children and mine."<ref name="Hornaday_1918-05"/> It turned out that radical changes from 1910s drilling methods were, in fact, applied promptly, and thus, the predicted timeframe was premature; but the underlying concerns (that the vastness of consumption would lead to shortages soon enough to worry about, regardless of the exact decade) did not disappear. |

||

===Hubbert's model=== |

|||

In 1956, [[M. King Hubbert]] created and first used the models behind peak oil to predict that United States oil production would peak between 1965 and 1971.<ref name=mkinghubbert1956>{{cite conference |url=http://www.hubbertpeak.com/hubbert/1956/1956.pdf |title=Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' |last= Hubbert | first = Marion King |authorlink=M. King Hubbert |conference = Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. [[American Petroleum Institute]] |publisher= [[Shell Oil Company|Shell Development Company]] |location = [[San Antonio]], [[Texas]] |pages =22–27 <!-- p. 31-36 in pdf scheme --> |date=June 1956 |accessdate=18 April 2008 |format=PDF}}</ref> |

In 1956, [[M. King Hubbert]] created and first used the models behind peak oil to predict that United States oil production would peak between 1965 and 1971.<ref name=mkinghubbert1956>{{cite conference |url=http://www.hubbertpeak.com/hubbert/1956/1956.pdf |title=Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' |last= Hubbert | first = Marion King |authorlink=M. King Hubbert |conference = Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. [[American Petroleum Institute]] |publisher= [[Shell Oil Company|Shell Development Company]] |location = [[San Antonio]], [[Texas]] |pages =22–27 <!-- p. 31-36 in pdf scheme --> |date=June 1956 |accessdate=18 April 2008 |format=PDF}}</ref> |

||

| Line 73: | Line 53: | ||

|format=PDF |

|format=PDF |

||

}}</ref> and other factors), then rebounded with a lower rate of growth in the mid 1980s. Thus oil production did not peak in 1995, and has climbed to more than double the rate initially projected. |

}}</ref> and other factors), then rebounded with a lower rate of growth in the mid 1980s. Thus oil production did not peak in 1995, and has climbed to more than double the rate initially projected. |

||

===Pessimistic predictions in 2000s=== |

|||

In 2001, [[Kenneth S. Deffeyes]], professor emeritus of geology at Princeton University, used Hubbert’s theory to predict that world oil production would peak in 2005.<ref>Kenneth S. Deffeyes, [http://www.amazon.com/Hubberts-Peak-Impending-World-Shortage/dp/B001NC2AZW/ref=sr_1_8?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1388901805&sr=1-8&keywords=hubbert%27s+peak Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage] (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2001).</ref> As of late 2009, Deffeyes was still convinced that 2005 had been the peak, and wrote: “I think it unlikely that oil production will ever climb back to the 2005 levels.”<ref>Kenneth S. Deffeyes, [http://www.princeton.edu/hubbert/current-events-09-11.html “Join us as we watch the crisis unfolding”], When Oil Peaked website, 13 Nov. 2009.</ref> |

In 2001, [[Kenneth S. Deffeyes]], professor emeritus of geology at Princeton University, used Hubbert’s theory to predict that world oil production would peak in 2005.<ref>Kenneth S. Deffeyes, [http://www.amazon.com/Hubberts-Peak-Impending-World-Shortage/dp/B001NC2AZW/ref=sr_1_8?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1388901805&sr=1-8&keywords=hubbert%27s+peak Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage] (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2001).</ref> As of late 2009, Deffeyes was still convinced that 2005 had been the peak, and wrote: “I think it unlikely that oil production will ever climb back to the 2005 levels.”<ref>Kenneth S. Deffeyes, [http://www.princeton.edu/hubbert/current-events-09-11.html “Join us as we watch the crisis unfolding”], When Oil Peaked website, 13 Nov. 2009.</ref> |

||

| Line 178: | Line 158: | ||

<ref name="PhysicalPeakOil">[http://issuu.com/where-energy-meets-water/docs/mwh2o-february2012/37'' The energy agriculture connect], pp.36-38. Retrieved 18 Feb 2012, by Nicol-André Berdellé, 4 February 2012</ref> |

<ref name="PhysicalPeakOil">[http://issuu.com/where-energy-meets-water/docs/mwh2o-february2012/37'' The energy agriculture connect], pp.36-38. Retrieved 18 Feb 2012, by Nicol-André Berdellé, 4 February 2012</ref> |

||

==Optimistic predictions |

===Optimistic predictions in 2000s=== |

||

Non-'peakists' can be divided into several different categories based on their specific criticism of peak oil. Some claim that any peak will not come soon or have a dramatic effect on the world economies. Others claim we will not reach a peak for technological reasons, while still others claim our oil reserves are quickly regenerated abiotically. |

Non-'peakists' can be divided into several different categories based on their specific criticism of peak oil. Some claim that any peak will not come soon or have a dramatic effect on the world economies. Others claim we will not reach a peak for technological reasons, while still others claim our oil reserves are quickly regenerated abiotically. |

||

===Plateau oil=== |

|||

[[File:Montly world petroleum supply 1995-2010 (1-13-2009 data).jpg|thumb|300px|Monthly world oil supply data from 1995 to 2008. Supply is defined as crude oil production (including [[lease condensates]]), [[natural gas]] plant liquids, other liquids, and [[refinery processing gains]].]] |

[[File:Montly world petroleum supply 1995-2010 (1-13-2009 data).jpg|thumb|300px|Monthly world oil supply data from 1995 to 2008. Supply is defined as crude oil production (including [[lease condensates]]), [[natural gas]] plant liquids, other liquids, and [[refinery processing gains]].]] |

||

| Line 451: | Line 430: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist|2}} |

{{reflist|2}} |

||

==External links== |

|||

* {{cite web|title=The Global Oil Depletion Report|url=http://www.ukerc.ac.uk/support/Global%20Oil%20Depletion|accessdate=21 April 2014|author=UK Energy Research Centre|year=2009}} |

|||

* {{cite web|last=Foucher|first=Sam|title=Peak Oil Update - Final Thoughts|url=http://www.theoildrum.com/node/10163|publisher=The Oil Drum|accessdate=21 April 2014|year=2013}} |

|||

{{Peak oil}} |

{{Peak oil}} |

||

Revision as of 01:39, 21 April 2014

Peak oil is the point at which oil production, sometimes including unconventional oil sources, hits its maximum. Predicting the timing of peak oil involves estimation of future production from existing oil fields as well as future discoveries. Although Hubbert peak theory was proposed in the 1950s, it was not until the early 21st century that serious interest in a reliable estimate of future oil production arose. As of 2014, it is not widely questioned that oil production will be in decline after 2050. The effect of peak oil on the world economy remains controversial.

Present range of predictions

There is a general consensus between industry leaders and analysts that world oil production will peak between 2010 and 2030, with a significant chance that the peak will occur before 2020. Dates after 2030 are considered implausible.[1][2] Determining a more specific range is difficult due to the lack of certainty over the actual size of world oil reserves.[3] Unconventional oil is not currently predicted to meet the expected shortfall even in a best-case scenario.[1] For unconventional oil to fill the gap without "potentially serious impacts on the global economy", oil production would have to remain stable after its peak, until 2035 at the earliest.[4]

Past predictions

The idea that human use of petroleum faces sustainability limits attracted practical concern at least as early as the 1910s, as did the related idea that the timing of those limits depends on the extraction technology. A correspondent named W.D. Hornaday, quoting oil industry executive J.S. Cullinan, described the concerns in a 1918 article for Tractor and Gas Engine Review titled "Petroleum consumption enormous."[5] The article said, "There has been considerable discussion of late as to the possible length of time that the petroleum supply of the United States and the world will hold out."[5] The article quoted Cullinan as saying, "It is just possible, so far as the United States is concerned, that the development and the exhaustion of the supplies may occur within the course of one human life. It is certain that unless radical changes from present methods are applied promptly, all sources of supply within the range of known drilling methods will be exhausted during the life of your children and mine."[5] It turned out that radical changes from 1910s drilling methods were, in fact, applied promptly, and thus, the predicted timeframe was premature; but the underlying concerns (that the vastness of consumption would lead to shortages soon enough to worry about, regardless of the exact decade) did not disappear.

Hubbert's model

In 1956, M. King Hubbert created and first used the models behind peak oil to predict that United States oil production would peak between 1965 and 1971.[6]

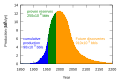

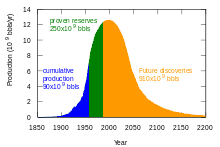

In 1956, Hubbert calculated that the world held an ultimate cumulative of 1.25 trillion barrels, of which 124 billion had already been produced. He projected that world oil production would peak at about 12.5 billion barrels per year, sometime around the year 2000. He repeated the prediction in 1962.[7] World oil production surpassed his predicted peak in 1967 and kept rising; world oil production did not peak on or near the year 2000, and for the year 2012 was 26.67 billion barrels, more that twice the peak rate Hubbert had projected back in 1956.[8]

In 1974, M. King Hubbert predicted that world peak oil would occur in 1995 "if current trends continue."[9] However, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, global oil consumption actually dropped (due to the shift to energy-efficient cars,[10] the shift to electricity and natural gas for heating,[11] and other factors), then rebounded with a lower rate of growth in the mid 1980s. Thus oil production did not peak in 1995, and has climbed to more than double the rate initially projected.

Pessimistic predictions in 2000s

In 2001, Kenneth S. Deffeyes, professor emeritus of geology at Princeton University, used Hubbert’s theory to predict that world oil production would peak in 2005.[12] As of late 2009, Deffeyes was still convinced that 2005 had been the peak, and wrote: “I think it unlikely that oil production will ever climb back to the 2005 levels.”[13]

Matthew Simmons said on October 26, 2006 that global oil production may have peaked in December 2005, though he cautioned that further monitoring of production is required to determine if a peak has actually occurred.[14]

The July 2007 IEA Medium-Term Oil Market Report projected a 2% non-OPEC liquids supply growth in 2007-2009, reaching 51.0 kbbl/d (8,110 m3/d) in 2008, receding thereafter as the slate of verifiable investment projects diminishes. They refer to this decline as a plateau. The report expects only a small amount of supply growth from OPEC producers, with 70% of the increase coming from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Angola as security and investment issues continue to impinge on oil exports from Iraq, Nigeria and Venezuela.[15]

In October 2007, the Energy Watch Group, a German research group founded by MP Hans-Josef Fell, released a report claiming that oil production peaked in 2006 and would decline by several percent annually. The authors predicted negative economic effects and social unrest as a result.[16][17] They stated that the IEA production plateau prediction uses purely economic models, which rely on an ability to raise production and discovery rates at will.[16]

Sadad Al Husseini, former head of Saudi Aramco's production and exploration, stated in an October 29, 2007 interview that oil production had likely already reached its peak in 2006,[18] and that assumptions by the IEA and EIA of production increases by OPEC to over 45 kbbl/d (7,200 m3/d) are "quite unrealistic."[18] Data from the United States Energy Information Administration show that world production leveled out in 2004, and an October 2007 retrospective report by the Energy Watch Group concluded that this data showed the peak of conventional oil production in the third quarter of 2006.[16]

ASPO predicted in their January 2008 newsletter that the peak in all oil (including non-conventional sources), would occur in 2010. This is earlier than the July 2007 newsletter prediction of 2011.[19] ASPO Ireland in its May 2008 newsletter, number 89, revised its depletion model and advanced the date of the peak of overall liquids from 2010 to 2007.[20]

Texas alternative energy activist and oilman T. Boone Pickens stated in 2005 that worldwide conventional oil production was very close to peaking.[21] On June 17, 2008, in testimony before the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Pickens stated that "I do believe you have peaked out at 85 million barrels a day globally."[22]

All of the predictions in the paragraphs above have proved incorrect, as of 2013, as worldwide oil production has continued to rise.

At least one oil company, French supermajor Total S.A., announced plans in 2008 to shift their focus to nuclear energy instead of oil and gas. A Total senior vice president explained that this is because they believe oil production will peak before 2020, and they would like to diversify their position in the energy markets.[23]

The UK Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil and Energy Security (ITPOES) reported in late October 2008 that peak oil is likely to occur by 2013. ITPOES consists of eight companies: Arup, FirstGroup, Foster + Partners, Scottish and Southern Energy, Solarcentury, Stagecoach Group, Virgin Group, and Yahoo. Their report includes a chapter written by Shell corporation.[24]

In October 2009, a report published by the Government-supported UK Energy Research Centre, following 'a review of over 500 studies, analysis of industry databases and comparison of global supply forecasts', concluded that 'a peak in conventional oil production before 2030 appears likely and there is a significant risk of a peak before 2020'.[25] The authors believe this forecast to be valid 'despite the large uncertainties in the available data'.[26] The study was claimed to be the first to undertake an 'independent, thorough and systematic review of the evidence and arguments in the 'peak oil’ debate'.[27] The authors noted that 'forecasts that delay a peak in conventional oil production until after 2030 are at best optimistic and at worst implausible' and warn of the risk that 'rising oil prices will encourage the rapid development of carbon-intensive alternatives that will make it difficult or impossible to prevent dangerous climate change[27] and that 'early investment in low-carbon alternatives to conventional oil is of considerable importance' in avoiding this scenario.[28]

A 2010 Kuwait University study predicted production will peak in 2014.[29]

A 2010 report by Oxford University researchers in the journal Energy Policy predicted that production will peak before 2015.[30]

Nicol-André Berdellé adjusted world oil production by deducting the energy equivalent of investments, and concluded that a more than doubling of investment in oil exploration and development between 2005 and 2010, masked a decline in net oil production. He argued that in net energy terms, peak oil has alrady taken place. [31]

Optimistic predictions in 2000s

Non-'peakists' can be divided into several different categories based on their specific criticism of peak oil. Some claim that any peak will not come soon or have a dramatic effect on the world economies. Others claim we will not reach a peak for technological reasons, while still others claim our oil reserves are quickly regenerated abiotically.

CERA, which counts unconventional sources in reserves while discounting EROEI, believes that global production will eventually follow an “undulating plateau” for one or more decades before declining slowly.[32] In 2005 the group predicted that "petroleum supplies will be expanding faster than demand over the next five years."[33]

In 2007, The Wall Street Journal reported that "a growing number of oil-industry chieftains" believed that oil production would soon reach a ceiling for a variety of reasons, and plateau at that level for some time. Several chief executives stated that projections of over 100 million barrels (16,000,000 m3) of production per day are unrealistic, contradicting the projections of the International Energy Agency and United States Energy Information Administration.[34]

In 2008, the IEA predicted a plateau by 2020 and a peak by 2030. The report called for a "global energy revolution" to prepare mitigations by 2020 and avoid "more difficult days" and large wealth transfers from OECD nations to oil producing nations.[35] This estimate was changed in 2009 to predict a peak by 2020, with severe supply-growth constraints beginning in 2010 (stemming from "patently unsustainable" energy use and a lack of production investment) leading to rapidly increasing oil prices and an "oil crunch" before the peak.[36]

It has been argued that even a "plateau oil" scenario may cause political and economic disruption due to increasing petroleum demand and price volatility.[37]

Energy Information Administration and USGS 2000 reports

The United States Energy Information Administration projects (as of 2006) world consumption of oil to increase to 98.3 million barrels per day (15.63×106 m3/d) in 2015 and 118 million barrels per day (18.8×106 m3/d) in 2030.[38] This would require a more than 35 percent increase in world oil production by 2030. A 2004 paper by the Energy Information Administration based on data collected in 2000 disagrees with Hubbert peak theory on several points. It:[39]

- explicitly incorporates demand into model as well as supply

- does not assume pre/post-peak symmetry of production levels

- models pre- and post-peak production with different functions (exponential growth and constant reserves-to-production ratio, respectively)

- assumes reserve growth, including via technological advancement and exploitation of small reservoirs

The EIA estimates of future oil supply are disagreed with by Sadad Al Husseini, a retired Vice President of Exploration of Aramco, who called it a 'dangerous over-estimate'.[40] Husseini also pointed out that population growth and the emergence of China and India means oil prices are now going to be structurally higher than they have been.

Colin Campbell argued that the 2000 United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimates was a methodologically flawed study that has done incalculable damage by misleading international agencies and governments. Campbell dismisses the notion that the world can seamlessly move to more difficult and expensive sources of oil and gas when the need arises. He argued that oil is in profitable abundance or not there at all, due ultimately to the fact that it is a liquid concentrated by nature in a few places that possess the right geological conditions. Campbell believes OPEC countries raised their reserves to get higher oil quotas and to avoid internal critique. He has also pointed out that the USGS failed to extrapolate past discovery trends in the world’s mature basins. He concluded (2002) that peak production was "imminent."[41] Campbell's own record is that he successively predicted that the peak in world production would occur in 1989, 2004, and 2010, none of which took place.[42]

No peak oil

The view that oil extraction will never enter a depletion phase is often referred to as "cornucopian" in ecology and sustainability literature.[43][44][45]

Abdullah S. Jum'ah, President, Director and CEO of Saudi Aramco states that the world has adequate reserves of conventional and nonconventional oil sources that will last for more than a century.[46][47] As recently as 2008 he pronounced "We have grossly underestimated mankind’s ability to find new reserves of petroleum, as well as our capacity to raise recovery rates and tap fields once thought inaccessible or impossible to produce.” Jum’ah believes that in-place conventional and non-conventional liquid resources may ultimately total between 13 trillion and 16 trillion barrels (2,500 km3) and that only a small fraction (1.1 trillion) has been extracted to date.[48]

I do not believe the world has to worry about ‘peak oil’ for a very long time.

— Abdullah S. Jum'ah, 2008-01[48]

Economist Michael Lynch says that the Hubbert Peak theory is flawed and that there is no imminent peak in oil production. He argued in 2004 that production is determined by demand as well as geology, and that fluctuations in oil supply are due to political and economic effects as well as the physical processes of exploration, discovery and production.[49] This idea is echoed by Jad Mouawad, who explains that as oil prices rise, new extraction technologies become viable, thus expanding the total recoverable oil reserves. This, according to Mouwad, is one explanation of the changes in peak production estimates.[50]

Leonardo Maugeri, the former group senior vice president, Corporate Strategies of Eni S.p.A., dismissed the peak oil thesis in a 2004 policy position piece in Science as "the current model of oil doomsters," and based on several flawed assumptions. He characterized the peak oil theory as part of a series of "recurring oil panics" that have "driven Western political circles toward oil imperialism and attempts to assert direct or indirect control over oil-producing regions". Maugeri claimed the geological structure of the earth has not been explored thoroughly enough to conclude that the declining trend in discoveries, which began in the 1960s, will continue. He also stated that complete global oil production, discovery trends, and geological data are not available globally.[51]

Abiogenesis

The theory that petroleum derives from biogenic processes is held by the overwhelming majority of petroleum geologists. However, abiogenic theorists, such as the late professor of astronomy Thomas Gold, assert that oil may be a continually renewing abiotic product, rather than a “fossil fuel” in limited supply. They hypothesize that if abiogenic petroleum sources are found and are quick to replenish, petroleum production will not decline.[52] Gold was not able to prove his theories in experiments [53]

One of the main counter arguments to the abiotic theory highlights the biomarkers which have been found in all samples of all the oil and gas accumulations to date. These suggest that oil has a biological origin, and is generated from kerogen by pyrolysis.[54][55]

Peak oil for individual nations

Peak Oil as a concept applies globally, but it is based on the summation of individual nations experiencing peak oil. In State of the World 2005, Worldwatch Institute observed that oil production was in decline in 33 of the 48 largest oil-producing countries.[56] Other countries have also passed their individual oil production peaks.

The following list shows significant oil-producing nations and their peak oil production years.[57]

- Australia: 2000[29]

- Egypt: 1987[58]

- France: 1988

- Germany: 1966

- Iran: 1974

- Indonesia: 1991[59]

- Libya: 1970 (disputed)[29]

- Mexico: 2003

- New Zealand: 1997[60]

- Nigeria: 1979

- Norway: 2000[61]

- Oman: 2000[62]

- Syria: 1996[63]

- Tobago: 1981[64]

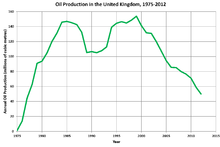

- UK: 1999

- USA: 1970[65]

- Venezuela: 1970

An ABC television program in 2006 predicted the following (then) future oil peaks:[66]

- Algeria: 2012 (actually peaked in 2006)[67]

- Angola: 2010 (actually peaked in 2008)[29][67]

- China: 2009 (production has continued to rise through 2012)[29][67]

- Russia: 2010 (production has continued to rise through 2012)[29][67]

Peak oil production has not been reached in the following nations (and is estimated in a 2010 Kuwait University study to occur in the following years):[29]

- Azerbaijan: 2013 (actually peaked in 2010)[68]

- India: 2015

- Iraq: 2036

- Kazakhstan: 2020

- Kuwait: 2033

- Saudi Arabia: 2027

- Qatar: 2019

In addition, the most recent International Energy Agency and US Energy Information Administration production data show record and rising production in Canada and China. [citation needed] While conventional oil production from Canada is listed as 1973, oil sands production are expected to permit increasing production until at least 2020 - see table Canadian Oil Production.

See also

References

- ^ a b Madureira, Nuno Luis (2014). Key Concepts in Energy. London: Springer International Publishing. pp. 125–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04978-6_6. ISBN 978-3-319-04977-9.

- ^ Sorrell, Steve (September 2010). "Oil futures: A comparison of global supply forecasts". Energy Policy. 38 (9): 4990–5003. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chapman, Ian (January 2014). "The end of Peak Oil? Why this topic is still relevant despite recent denials". Energy Policy. 64: 93–101. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.010.

- ^ Miller, R. G. (2014). "The future of oil supply". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 372 (2006): 20130179–20130179. doi:10.1098/rsta.2013.0179.

[W]e estimate that around 11–15 mb per day of non-conventional liquids production could be achieved in the next 20 years . . . If crude oil production falls, then total liquids production seems likely to fall as well, leading to significant price increases and potentially serious impacts on the global economy.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Hornaday, W.D. (May 1918), "Petroleum consumption enormous", Tractor and Gas Engine Review, 11 (5): 72.

- ^ Hubbert, Marion King (June 1956). Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' (PDF). Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. American Petroleum Institute. San Antonio, Texas: Shell Development Company. pp. 22–27. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ^ M. King Hubbert, 1962, Energy Resources, National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council, Publication 1000-D, p.75

- ^ OPEC, OPEC Statistical Bulletin, 2013. OPEC world oil production is significantly lower than that calculated by the US Energy Information Administration, because OPEC does not include surface-mined oil, such as Canadian heavy oil sand production.

- ^

Noel Grove, reporting M. King Hubbert (June 1974). "Oil, the Dwindling Treasure". National Geographic.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysource=,|laydate=,|quotes=, and|laysummary=(help) - ^ "Light-Duty Automotive Technology and Fuel Economy Trends: 1975 Through 2006 - Executive Summary". United States Environmental Protection Agency EPA420-S-06-003. July 2006.

- ^

Ferenc L. Toth, Hans-Holger Rogner, (2006). "Oil and nuclear power: Past, present, and future" (PDF). Energy Economics. 28 (1–25): pg. 3.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kenneth S. Deffeyes, Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2001).

- ^ Kenneth S. Deffeyes, “Join us as we watch the crisis unfolding”, When Oil Peaked website, 13 Nov. 2009.

- ^ "Peak oil". 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Medium-Term Oil Market Report". IEA. July 2007.

- ^ a b c The Energy Watch Group (October 2007). "Crude Oil The Supply Outlook" (PDF). The Energy Watch Group.

- ^ Seager Ashley (2007-10-22). "Steep decline in oil production brings risk of war and unrest, says new study". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ a b Dave Cohen (October 31, 2007). "The Perfect Storm". ASPO-USA.

- ^ "Newsletter" (PDF). Vol. 85. Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. January 2008.

- ^ "Newsletter" (PDF). Vol. 89. Ireland: Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. May 2008.

- ^ "Boone Pickens Warns of Petroleum Production Peak". Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. 2005-05-03.

- ^ Melvin Jasmin (2008-06-17). "World crude production has peaked: Pickens". Reuters.

- ^ Simon Webb (November 10, 2008). "Total sees nuclear energy for growth after peak oil". Reuters.

- ^ UK Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil and Energy Security. "The Oil Crunch: Securing the UK's energy future".

- ^ The Global Oil Depletion Report, October 08, 2009, UK Energy Research Centre

- ^ Global Oil Depletion: An assessment of the evidence for a near-term peak in global oil production, page vii, August 2009, published October 08, 2009, UK Energy Research Centre, ISBN 1-903144-03-5

- ^ a b UKERC Report Finds ‘Significant Risk’ of Oil Production Peaking in Ten Years, October 08, 2009, UK Energy Research Centre

- ^ Global Oil Depletion: An assessment of the evidence for a near-term peak in global oil production, page xi, Agugust 2009, published October 08, 2009, UK Energy Research Centre, ISBN 1-903144-03-5

- ^ a b c d e f g Sami Nashawi, Adel Malallah and Mohammed Al-Bisharah. "Forecasting World Crude Oil Production Using Multicyclic Hubbert Model". Energy Fuels. 24 (3): 1788–1800. doi:10.1021/ef901240p.

- ^ Nick A. Owen, Oliver R. Inderwildi, David A. King (2010). "The status of conventional world oil reserves—Hype or cause for concern?". Energy Policy. 38 (8): 4743. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.02.026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The energy agriculture connect, pp.36-38. Retrieved 18 Feb 2012, by Nicol-André Berdellé, 4 February 2012

- ^ "CERA says peak oil theory is faulty". Energy Bulletin. 2006-11-14.

- ^ "One energy forecast: Oil supplies grow". Christian Science Monitor. 2005-06-22.

- ^ Gold, Russell and Ann Davis (2007-11-19). "Oil Officials See Limit Looming on Production". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ^ Monbiot, George (2008-12-15). "When will the oil run out?". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ Connor, Steve (3 August 2009). "Warning: Oil supplies are running out fast". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Mitchell John V (August 2006). "A new era for oil prices" (PDF).

- ^ "World Oil Consumption by region, Reference Case" (PDF). EIA. 2006.

- ^

John H. Wood, Gary R. Long, David F. Morehouse (2004-08-18). "Long-Term World Oil Supply Scenarios - The Future Is Neither as Bleak or Rosy as Some Assert". Electronic Industries Alliance.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Oil expert: US overestimates future oil supplies". Channel 4 News.

- ^ "Campbell replies to USGS: Global Petroleum Reserves-View to the Future". Oil Crisis. 2002-12-01. Archived from the original on 2004-12-25.

- ^ Guy Caruso, Administrator, US Energy Information Administration, When will world oil production peak?, 13 June 2005, p.3.

- ^ Clark, J.G. (1995). "Economic Development vs. Sustainable Societies: Reflections on the Players in a Crucial Contest". Annual Reviews in Ecology and Systematics. 26 (1): 225–248. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.001301.

- ^ Attarian, J. (2002). "The Coming End of Cheap Oil" (PDF). The Social Contract, Summer.

- ^ Chenoweth, J.; Feitelson, E. (2005). "Neo-Malthusians and Cornucopians put to the test: Global 2000 and the Resourceful Earth revisited". Futures. 37 (1): 51–72. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2004.03.019.

- ^ Uchenna Izundu (2007-11-14). "Aramco chief says world's Oil reserves will last for more than a century". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ Jum’ah Abdallah S. "Rising to the Challenge: Securing the Energy Future". World Energy Source.

- ^ a b Peter Glover (2008-01-17). "Aramco Chief Debunks Peak Oil". Energy Tribune. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Lynch Michael C (2004). "The New Pessimism about Petroleum Resources: Debunking the Hubbert Model (and Hubbert Modelers)" (PDF). American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2004.

- ^ Mouawad, Jad (2007-03-05). "Oil Innovations Pump New Life Into Old Wells". New York Times.

- ^ Leonardo Maugeri (2004-05-21). "Oil: Never Cry Wolf—Why the Petroleum Age Is Far From Over". Science. 304 (5674). Science: 1114–5. doi:10.1126/science.1096427. PMID 15155935.

- ^ J. R. Nyquist (2006-05-08). "Debunking Peak Oil". Financial Sense.

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Gold#Drilling_in_Siljan

- ^ M. R. Mello and J.M. Moldowan (2005). "Petroleum: To Be Or Not To Be Abiogenic".

- ^ Pinsker, Lisa M (October 2005). "Feuding over the origins of fossil fuels". GeoTimes. Vol. 50, no. 10, pp. 28-32.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ WorldWatch Institute (2005-01-01). State of the World 2005: Redefining Global Security. New York: Norton. p. 107. ISBN 0-393-32666-7.

- ^ Unless otherwise specified, source is ABC TV's Four Corners, 10 July 2006.

- ^ "Egypt Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Indonesia Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "New Zealand Crude Oil Production by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Helge Lund: - "Peak Oil" har kommet til Norge ( , StatoilHydro , Olje )". E24.no. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Oman Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Syrian Arab Republic Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Trinidad and Tobago Crude Oil Production by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/aer/txt/stb0501.xls

- ^ ABC TV's Four Corners, 10 July 2006.

- ^ a b c d US Energy Information Administration, International energy statistics

- ^ "SOCAR - Economics and Statistics Oil Production". SOCAR. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

External links

- UK Energy Research Centre (2009). "The Global Oil Depletion Report". Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- Foucher, Sam (2013). "Peak Oil Update - Final Thoughts". The Oil Drum. Retrieved 21 April 2014.