Lingam: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

→History: check source and revise, add Mahabharata section |

→History: expand, add sources |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

According to Chakrabarti, "some of the stones found in Mohenjodaro are unmistakably phallic stones". These are dated to some time before 2300 BCE. Similarly, states Chakrabarti, the Kalibangan site of Harappa has a small terracota representation that "would undoubtedly be considered the replica of a modern Shivlinga [a tubular stone]."<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yDAlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39|title=Hindu Images and Their Worship with Special Reference to Vaisnavism: A Philosophical-theological Inquiry|last=Lipner|first=Julius J.|authorlink=Julius J. Lipner|last2=|first2=|date=|publisher=Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group|year=2017|isbn=9781351967822|location=London ; New York|page=39|pages=|language=en|oclc=985345208}}</ref> |

According to Chakrabarti, "some of the stones found in Mohenjodaro are unmistakably phallic stones". These are dated to some time before 2300 BCE. Similarly, states Chakrabarti, the Kalibangan site of Harappa has a small terracota representation that "would undoubtedly be considered the replica of a modern Shivlinga [a tubular stone]."<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yDAlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39|title=Hindu Images and Their Worship with Special Reference to Vaisnavism: A Philosophical-theological Inquiry|last=Lipner|first=Julius J.|authorlink=Julius J. Lipner|last2=|first2=|date=|publisher=Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group|year=2017|isbn=9781351967822|location=London ; New York|page=39|pages=|language=en|oclc=985345208}}</ref> |

||

The colonial era archaeologists [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|John Marshall]] and [[Ernest J. H. Mackay|Ernest Mackay]] proposed that certain artifacts found at Harappan sites may be evidence of yoni-linga worship in Indus Valley Civilization.<ref name=aparpola1985>{{cite journal|author=Asko Parpola|authorlink=Asko Parpola|title = The Sky Garment - A study of the Harappan religion and its relation to the Mesopotamian and later Indian religions| journal= Studia Orientalia| publisher= The Finnish Oriental Society| volume=57| year=1985|pages=101-107}}</ref> Scholars such as [[Arthur Llewellyn Basham]] dispute whether such artifacts discovered at the archaeological sites of Indus Valley sites are yoni.<ref name=aparpola1985/><ref>{{cite book|author=Arthur Llewellyn Basham|title=The Wonder that was India: A Survey of the History and Culture of the Indian Subcontinent Before the Coming of the Muslims|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LscvuQEACAAJ|year=1967|publisher=Sidgwick & Jackson (1986 Reprint)|isbn=978-0-283-99257-5|page=24}}, Quote: "It has been suggested that certain large ring-shaped stones are formalized representations of the female regenerative organ and were symbols of the Mother Goddess, but this is most doubtful."</ref> For example, Jones and Ryan state that lingam/yoni shapes have been recovered from the archaeological sites at [[Harappa]] and [[Mohenjo-daro]], part of the [[Indus Valley Civilisation]].<ref>{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia of Hinduism|page=516|author=Constance Jones, James D. Ryan|publisher=Infobase Publishing|year=2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The R̥gvedic deities and their iconic forms|page=185|publisher=Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers|author=Jyotsna Chawla|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EX3XAAAAMAAJ}}</ref> In contrast, Wendy Doniger states that this relatively rare artifact can be interpreted in many ways and has unduly been used for wild speculations such as being a linga. Another item found and called the ''Pashupati seal'', states Doniger, has a general resemblance with Shiva and "the Indus people may well have created the symbolism of the divine phallus", but given the available evidence we cannot be certain, nor do we know that |

The colonial era archaeologists [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|John Marshall]] and [[Ernest J. H. Mackay|Ernest Mackay]] proposed that certain artifacts found at Harappan sites may be evidence of yoni-linga worship in Indus Valley Civilization.<ref name=aparpola1985>{{cite journal|author=Asko Parpola|authorlink=Asko Parpola|title = The Sky Garment - A study of the Harappan religion and its relation to the Mesopotamian and later Indian religions| journal= Studia Orientalia| publisher= The Finnish Oriental Society| volume=57| year=1985|pages=101-107}}</ref> Scholars such as [[Arthur Llewellyn Basham]] dispute whether such artifacts discovered at the archaeological sites of Indus Valley sites are yoni.<ref name=aparpola1985/><ref>{{cite book|author=Arthur Llewellyn Basham|title=The Wonder that was India: A Survey of the History and Culture of the Indian Subcontinent Before the Coming of the Muslims|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LscvuQEACAAJ|year=1967|publisher=Sidgwick & Jackson (1986 Reprint)|isbn=978-0-283-99257-5|page=24}}, Quote: "It has been suggested that certain large ring-shaped stones are formalized representations of the female regenerative organ and were symbols of the Mother Goddess, but this is most doubtful."</ref> For example, Jones and Ryan state that lingam/yoni shapes have been recovered from the archaeological sites at [[Harappa]] and [[Mohenjo-daro]], part of the [[Indus Valley Civilisation]].<ref>{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia of Hinduism|page=516|author=Constance Jones, James D. Ryan|publisher=Infobase Publishing|year=2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The R̥gvedic deities and their iconic forms|page=185|publisher=Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers|author=Jyotsna Chawla|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EX3XAAAAMAAJ}}</ref> In contrast, Indologist Wendy Doniger states that this relatively rare artifact can be interpreted in many ways and has unduly been used for wild speculations such as being a linga. Another postage stamp sized item found and called the ''Pashupati seal'', states Doniger, has an image with a general resemblance with Shiva and "the Indus people may well have created the symbolism of the divine phallus", but given the available evidence we cannot be certain, nor do we know that it had the same meaning as some currently project them to might have meant.<ref>{{cite journal|author =Wendy Doniger| title= God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva| journal= Social Research|volume =78| number=2|year= 2011|publisher= The Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=485-502|jstor=23347187}}</ref> |

||

According to the Indologist [[Asko Parpola]], "it is true that Marshall's and Mackay's hypotheses of linga and yoni worship by the Harappans has rested on rather slender grounds, and that for instance the interpretation of the so-called ring-stones as yonis seems untenable".<ref name=aparpola1985/> He quotes Dales 1984 paper, which states "with the single exception of the unidentified photography of a realistic phallic object in Marshall's report, there is no archaeological evidence to support claims of special sexually-oriented aspects of Harappan religion".<ref name=aparpola1985/> However, adds Parpola, a re-examination at Indus Valley sites suggest that the Mackay's hypothesis cannot be ruled out because erotic and sexual scenes such as ithyphallic males, naked females, a human couple having intercourse and trefoil imprints have now been identified at the Harappan sites.<ref name=aparpola1985/> The "finely polished circular stand" found by Mackay may be yoni although it was found without the linga. The absence of linga, states Parpola, maybe because it was made from wood which did not survive.<ref name=aparpola1985/> |

According to the Indologist [[Asko Parpola]], "it is true that Marshall's and Mackay's hypotheses of linga and yoni worship by the Harappans has rested on rather slender grounds, and that for instance the interpretation of the so-called ring-stones as yonis seems untenable".<ref name=aparpola1985/> He quotes Dales 1984 paper, which states "with the single exception of the unidentified photography of a realistic phallic object in Marshall's report, there is no archaeological evidence to support claims of special sexually-oriented aspects of Harappan religion".<ref name=aparpola1985/> However, adds Parpola, a re-examination at Indus Valley sites suggest that the Mackay's hypothesis cannot be ruled out because erotic and sexual scenes such as ithyphallic males, naked females, a human couple having intercourse and trefoil imprints have now been identified at the Harappan sites.<ref name=aparpola1985/> The "finely polished circular stand" found by Mackay may be yoni although it was found without the linga. The absence of linga, states Parpola, maybe because it was made from wood which did not survive.<ref name=aparpola1985/> |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

===Early iconography and temples=== |

===Early iconography and temples=== |

||

[[File:This Lingam.jpg|thumb|Gudimallam lingam (Parashurameshwara temple, Andhra Pradesh) has been dated to between the 3rd and 1st century BCE. The phallic pillar is anatomically accurate and depicts Shiva with an antelope and axe in his hands standing over a dwarf demon.<ref>{{cite journal|author =Wendy Doniger| title= God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva| journal= Social Research|volume =78| number=2|year= 2011|publisher= The Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=491-493|jstor=23347187}}</ref>]] |

[[File:This Lingam.jpg|thumb|Gudimallam lingam (Parashurameshwara temple, Andhra Pradesh) has been dated to between the 3rd and 1st century BCE. The phallic pillar is anatomically accurate and depicts Shiva with an antelope and axe in his hands standing over a dwarf demon.<ref name=doniger491>{{cite journal|author =Wendy Doniger| title= God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva| journal= Social Research|volume =78| number=2|year= 2011|publisher= The Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=491-493|jstor=23347187}}</ref>]] |

||

The oldest example of a lingam that is still used for worship is in [[Gudimallam]]. It dates to the 2nd{{nbsp}}century{{nbsp}}BC.<ref name="Klostermaier">{{cite book |last1=Klostermaier|first1=Klaus K.|title=A Survey of Hinduism|date=2007|publisher=State University of New York Press|location=Albany, N.Y.|isbn=978-0-7914-7082-4 |edition=3.|page=111|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E_6-JbUiHB4C}}</ref> A figure of Shiva is carved into the front of the lingam.<ref name="elgood">{{cite book |last1=Elgood|first1=Heather|title=Hinduism and the Religious Arts|date=2000|publisher=Cassell|location=London|isbn=978-0-8264-9865-6|page=47 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tAcF8RgbtZ0C}}</ref> |

The oldest example of a lingam that is still used for worship is in [[Gudimallam]]. It dates to the 2nd{{nbsp}}century{{nbsp}}BC.<ref name="Klostermaier">{{cite book |last1=Klostermaier|first1=Klaus K.|title=A Survey of Hinduism|date=2007|publisher=State University of New York Press|location=Albany, N.Y.|isbn=978-0-7914-7082-4 |edition=3.|page=111|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E_6-JbUiHB4C}}</ref> A figure of Shiva is carved into the front of the lingam.<ref name="elgood">{{cite book |last1=Elgood|first1=Heather|title=Hinduism and the Religious Arts|date=2000|publisher=Cassell|location=London|isbn=978-0-8264-9865-6|page=47 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tAcF8RgbtZ0C}}</ref> |

||

===Mahabharata=== |

===Mahabharata=== |

||

According to Doniger, the ''Mahabharata'' is the first ancient Hindu text where the ''lingam'' is "unequivocally designating the sexual organ of Shiva".<ref name= |

According to Doniger, the ''Mahabharata'' is the first ancient Hindu text where the ''lingam'' is "unequivocally designating the sexual organ of Shiva".<ref name=doniger491/> Chapter 10.17 of the ''Mahabharata'' also refers to the word ''sthanu'' in the sense of an "inanimate pillar" as well as a "name of Shiva, signifying the immobile, ascetic, desexualized form of the ''lingam''", as it recites the legend involving [[Shiva]], [[Brahma]] and [[Prajapati]].<ref name=doniger491/><ref>{{cite book|author=Alf Hiltebeitel|title=Freud's Mahabharata|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4hhnDwAAQBAJ |year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-087834-4|pages=123-124, footnote 179}}</ref> This mythology weaves two polarities, one where the lingam represents the potentially procreative phallus (fertile lingam) and its opposite "a pillar-like renouncer of sexuality" (ascetic lingam), states Doniger.<ref name=doniger491/> |

||

===Puranas=== |

===Puranas=== |

||

The ''[[Shiva Purana]]'' describes the origin of the lingam, known as Shiva-linga, as the beginning-less and endless cosmic pillar (''[[Stambha]]'') of fire, the cause of all causes.<ref name="Chaturvedi">{{cite book|last=Chaturvedi|title=Shiv Purana|publisher=Diamond Pocket Books|isbn=978-81-7182-721-3|pages=11 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bchgql0em9YC&pg=PA29&dq=shiva+purana#v=onepage&q=column&f=false|edition=2006}}</ref> Lord Shiva is pictured as emerging from the lingam{{snd}}the cosmic pillar of fire{{snd}}proving his superiority over the gods [[Brahma]] and [[Vishnu]].<ref name="british museum">{{cite web|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/asia/s/stone_statue_of_shiva_as_lingo.aspx|title=Stone statue of Shiva as Lingodbhava|last=Blurton|first=T. R.|year=1992|work=Extract from Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press)|publisher=British Museum site|accessdate=2 July 2010}}</ref> This is known as [[Lingodbhava]]. The ''[[Linga Purana]]'' also supports this interpretation of lingam as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva.<ref name="british museum" /><ref name="E. U. Harding" /><ref name="paris_congress" /> According to the ''Linga Purana'', the lingam is a complete symbolic representation of the formless Universe Bearer{{snd}}the oval-shaped stone is the symbol of the Universe, and the bottom base represents the Supreme Power that holds the entire Universe in it.<ref name="Sivananda 1996">{{cite book|last=Sivananda|first=Swami|title=Lord Siva and His Worship|publisher=The Divine Life Trust Society|year=1996|chapter=Worship of Siva Linga|url=http://www.dlshq.org/download/lordsiva.htm#_VPID_80}}</ref> A similar interpretation is also found in the [[Skanda Purana]]: "The endless sky (that great void which contains the entire universe) is the Linga, the Earth is its base. At the end of time the entire universe and all the Gods finally merge in the Linga itself." <ref name="Skanda">{{cite web|url=http://is1.mum.edu/vedicreserve/skanda.htm|title=Reading the Vedic Literature in Sanskrit|website=is1.mum.edu|accessdate=2 June 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303192901/http://is1.mum.edu/vedicreserve/skanda.htm|archive-date=3 March 2016|dead-url=yes|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In the ''Linga Purana'', an Atharvaveda hymn is expanded with stories about the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva).<ref name="paris_congress"/> |

The ''[[Shiva Purana]]'' describes the origin of the lingam, known as Shiva-linga, as the beginning-less and endless cosmic pillar (''[[Stambha]]'') of fire, the cause of all causes.<ref name="Chaturvedi">{{cite book|last=Chaturvedi|title=Shiv Purana|publisher=Diamond Pocket Books|isbn=978-81-7182-721-3|pages=11 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bchgql0em9YC&pg=PA29&dq=shiva+purana#v=onepage&q=column&f=false|edition=2006}}</ref> Lord Shiva is pictured as emerging from the lingam{{snd}}the cosmic pillar of fire{{snd}}proving his superiority over the gods [[Brahma]] and [[Vishnu]].<ref name="british museum">{{cite web|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/asia/s/stone_statue_of_shiva_as_lingo.aspx|title=Stone statue of Shiva as Lingodbhava|last=Blurton|first=T. R.|year=1992|work=Extract from Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press)|publisher=British Museum site|accessdate=2 July 2010}}</ref> This is known as [[Lingodbhava]]. The ''[[Linga Purana]]'' also supports this interpretation of lingam as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva.<ref name="british museum" /><ref name="E. U. Harding" /><ref name="paris_congress" /> According to the ''Linga Purana'', the lingam is a complete symbolic representation of the formless Universe Bearer{{snd}}the oval-shaped stone is the symbol of the Universe, and the bottom base represents the Supreme Power that holds the entire Universe in it.<ref name="Sivananda 1996">{{cite book|last=Sivananda|first=Swami|title=Lord Siva and His Worship|publisher=The Divine Life Trust Society|year=1996|chapter=Worship of Siva Linga|url=http://www.dlshq.org/download/lordsiva.htm#_VPID_80}}</ref> A similar interpretation is also found in the [[Skanda Purana]]: "The endless sky (that great void which contains the entire universe) is the Linga, the Earth is its base. At the end of time the entire universe and all the Gods finally merge in the Linga itself." <ref name="Skanda">{{cite web|url=http://is1.mum.edu/vedicreserve/skanda.htm|title=Reading the Vedic Literature in Sanskrit|website=is1.mum.edu|accessdate=2 June 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303192901/http://is1.mum.edu/vedicreserve/skanda.htm|archive-date=3 March 2016|dead-url=yes|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In the ''Linga Purana'', an Atharvaveda hymn is expanded with stories about the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva).<ref name="paris_congress"/> |

||

===Other literature=== |

|||

There is persuasive evidence in later Sanskrit literature, according to Doniger, that the early Indians associated the lingam icon with the male sexual organ.<ref name=doniger493>{{cite journal|author =Wendy Doniger| title= God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva| journal= Social Research|volume =78| number=2|year= 2011|publisher= The Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=493-498|jstor=23347187}}</ref> For example, the 11th-century Kashmir text ''Narmamala'' by Kshemendra on satire and fiction writing explains his ideas on parallelism with divine lingam and human lingam in a sexual context. Various Shaiva texts, such as the ''Skanda Purana'' in section 1.8 states that all creatures have the signs of Shiva or Shakti through their lingam (male sexual organ) or pindi (female sexual organ).<ref name=doniger493/><ref>{{cite book|author=J. L. Brockington|title=Hinduism and Christianity|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hfe-DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA33 |year=2016|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-1-349-22280-3|page=33}}</ref> However, the Sanskrit literature corpus is not consistent. A part of the literature corpus regards ''lingam'' to be sexual and the phallus of Shiva, while another group of texts do not. Sexuality in the former is inherently sacred and spiritual, while the later emphasize the ascetic nature of Shiva and renunciation to be spiritual symbolism of ''lingam''. This tension between the pursuit of spirituality through householder lifestyle and the pursuit of renunciate sannyasi lifestyle is historic, reflects the different interpretations of lingam and what lingam worship means to its devotees. It remains a continuing debate within Hinduism to this day, states Doniger.<ref name=doniger493/> To one group, it is a part of Shiva's body and symbolically ''saguna'' Shiva (he in a physical form with attributes). To the other group, it is an abstract symbol of ''nirguna'' Shiva (he in the universal Absolute reality form without attributes).<ref name=doniger493/> In Tamil Shaiva tradition, for example, the common term for lingam is ''kuRi'' or "sign, mark" which is nonsexual.<ref name=doniger493/> Similarly, in [[Lingayatism]] tradition, the lingam is a spiritual symbol and "was never said to have any sexual connotations", according to Doniger.<ref name=donigerp498/> To some Shaivites, it symbolizes the axis of the universe.<ref name="Bayly2003p55">{{cite book|author=Susan Bayly|title=Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Fxqtx8SflEsC|year=2003|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-89103-5|pages=129–130 with footnote 55}}</ref> |

|||

===Muslim rule=== |

|||

After the 11th-century invasion of the subcontinent by Islamic armies, the iconoclast Muslims considered the lingam to be idolatrous representations of the male sexual organ. They took pride in destroying as many lingams and Shiva temples as they could, reusing them to build steps for mosques, in a region stretching from Somanath (Gujarat) to Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh) to Chidambaram (Tamil Nadu), states Doniger.<ref name=donigerp498>{{cite journal|author =Wendy Doniger| title= God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva| journal= Social Research|volume =78| number=2|year= 2011|publisher= The Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=498-499|jstor=23347187}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Mehrdad Shokoohy|title=Muslim Architecture of South India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=InklyjG57csC&pg=PA17 |year=2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-49984-5|pages=17–18}}</ref> |

|||

===Orientalist literature=== |

===Orientalist literature=== |

||

Revision as of 18:01, 30 September 2018

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

|

A lingam (Sanskrit: लिङ्गम्, IAST: liṅgaṃ, lit. "sign, symbol or mark"; also linga, Shiva linga) is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Hindu deity Shiva, used for worship in temples, smaller shrines, or as self-manifested natural objects.[1][2] The lingam is often represented as resting on disc shaped platform called a yoni[3] or pitha.[4] Lingayats wear a lingam inside a necklace, called Ishtalinga.[5][6]

Nomenclature and significance

According to Shaiva Siddhanta which is one the major school of Shaivism (Shaivism is one of 4 major sampradaya of Hinduism), The lingam is a column-like or oval (egg-shaped) symbol of Shiva, the Formless All-pervasive Reality, made of stone, metal, or clay. The Shiva Linga is a symbol of Lord Shiva – a mark that reminds of the Omnipotent Lord, which is formless. In Shaivite Hindu temples, the linga is a smooth cylindrical mass symbolising Shiva. It is found at the centre of the temple, often resting in the middle of a rimmed, disc-shaped structure, a representation of Shakti.[7] In traditional Indian society, the lingam is seen as a symbol of the energy and potential of Shiva himself.[7]

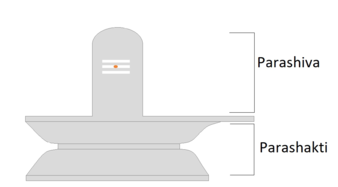

According to Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, the lingam signifies three perfections of Shiva.[8][better source needed] The upper oval part of the Shivalingam represent Parashiva and lower pedestrial part of Shivalingam or pitha represent Parashakti.[9][better source needed] In Parashiva perfection, Shiva is the absolute reality, the timeless, formless and spaceless. In Parashakti perfection, Shiva is all-pervasive, pure consciousness, power and primal substance of all that exists and it has form unlike Parashiva which is formless.[10][better source needed]

History

According to Nagendra Singh, some believe linga-worship was a feature of indigenous Indian religion.[11]

Archaeology and Indus valley

According to Chakrabarti, "some of the stones found in Mohenjodaro are unmistakably phallic stones". These are dated to some time before 2300 BCE. Similarly, states Chakrabarti, the Kalibangan site of Harappa has a small terracota representation that "would undoubtedly be considered the replica of a modern Shivlinga [a tubular stone]."[12]

The colonial era archaeologists John Marshall and Ernest Mackay proposed that certain artifacts found at Harappan sites may be evidence of yoni-linga worship in Indus Valley Civilization.[13] Scholars such as Arthur Llewellyn Basham dispute whether such artifacts discovered at the archaeological sites of Indus Valley sites are yoni.[13][14] For example, Jones and Ryan state that lingam/yoni shapes have been recovered from the archaeological sites at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, part of the Indus Valley Civilisation.[15][16] In contrast, Indologist Wendy Doniger states that this relatively rare artifact can be interpreted in many ways and has unduly been used for wild speculations such as being a linga. Another postage stamp sized item found and called the Pashupati seal, states Doniger, has an image with a general resemblance with Shiva and "the Indus people may well have created the symbolism of the divine phallus", but given the available evidence we cannot be certain, nor do we know that it had the same meaning as some currently project them to might have meant.[17]

According to the Indologist Asko Parpola, "it is true that Marshall's and Mackay's hypotheses of linga and yoni worship by the Harappans has rested on rather slender grounds, and that for instance the interpretation of the so-called ring-stones as yonis seems untenable".[13] He quotes Dales 1984 paper, which states "with the single exception of the unidentified photography of a realistic phallic object in Marshall's report, there is no archaeological evidence to support claims of special sexually-oriented aspects of Harappan religion".[13] However, adds Parpola, a re-examination at Indus Valley sites suggest that the Mackay's hypothesis cannot be ruled out because erotic and sexual scenes such as ithyphallic males, naked females, a human couple having intercourse and trefoil imprints have now been identified at the Harappan sites.[13] The "finely polished circular stand" found by Mackay may be yoni although it was found without the linga. The absence of linga, states Parpola, maybe because it was made from wood which did not survive.[13]

Vedic literature

The word lingam is not found in the Rigveda.[18] The word lingam appears in early Upanishads, but the context suggests that it simply means "sign" such as "smoke is a sign of fire", states Doniger.[18]

There is a hymn in the Atharvaveda that praises a pillar (Sanskrit: stambha), and this is one possible origin of linga worship.[11] According to Swami Vivekananda, the Shiva-linga had origins in the idea of Yupa-Stambha or Skambha of the Vedic rituals, where the term meant the sacrificial post which was then idealized as the eternal Brahman. The Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga, quite possibly with influence from Buddhism's stupa shaped like the top of a stone linga, according to Vivekananda.[19][20]

Early iconography and temples

The oldest example of a lingam that is still used for worship is in Gudimallam. It dates to the 2nd century BC.[22] A figure of Shiva is carved into the front of the lingam.[23]

Mahabharata

According to Doniger, the Mahabharata is the first ancient Hindu text where the lingam is "unequivocally designating the sexual organ of Shiva".[21] Chapter 10.17 of the Mahabharata also refers to the word sthanu in the sense of an "inanimate pillar" as well as a "name of Shiva, signifying the immobile, ascetic, desexualized form of the lingam", as it recites the legend involving Shiva, Brahma and Prajapati.[21][24] This mythology weaves two polarities, one where the lingam represents the potentially procreative phallus (fertile lingam) and its opposite "a pillar-like renouncer of sexuality" (ascetic lingam), states Doniger.[21]

Puranas

The Shiva Purana describes the origin of the lingam, known as Shiva-linga, as the beginning-less and endless cosmic pillar (Stambha) of fire, the cause of all causes.[25] Lord Shiva is pictured as emerging from the lingam – the cosmic pillar of fire – proving his superiority over the gods Brahma and Vishnu.[26] This is known as Lingodbhava. The Linga Purana also supports this interpretation of lingam as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva.[26][19][20] According to the Linga Purana, the lingam is a complete symbolic representation of the formless Universe Bearer – the oval-shaped stone is the symbol of the Universe, and the bottom base represents the Supreme Power that holds the entire Universe in it.[27] A similar interpretation is also found in the Skanda Purana: "The endless sky (that great void which contains the entire universe) is the Linga, the Earth is its base. At the end of time the entire universe and all the Gods finally merge in the Linga itself." [28] In the Linga Purana, an Atharvaveda hymn is expanded with stories about the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva).[20]

Other literature

There is persuasive evidence in later Sanskrit literature, according to Doniger, that the early Indians associated the lingam icon with the male sexual organ.[29] For example, the 11th-century Kashmir text Narmamala by Kshemendra on satire and fiction writing explains his ideas on parallelism with divine lingam and human lingam in a sexual context. Various Shaiva texts, such as the Skanda Purana in section 1.8 states that all creatures have the signs of Shiva or Shakti through their lingam (male sexual organ) or pindi (female sexual organ).[29][30] However, the Sanskrit literature corpus is not consistent. A part of the literature corpus regards lingam to be sexual and the phallus of Shiva, while another group of texts do not. Sexuality in the former is inherently sacred and spiritual, while the later emphasize the ascetic nature of Shiva and renunciation to be spiritual symbolism of lingam. This tension between the pursuit of spirituality through householder lifestyle and the pursuit of renunciate sannyasi lifestyle is historic, reflects the different interpretations of lingam and what lingam worship means to its devotees. It remains a continuing debate within Hinduism to this day, states Doniger.[29] To one group, it is a part of Shiva's body and symbolically saguna Shiva (he in a physical form with attributes). To the other group, it is an abstract symbol of nirguna Shiva (he in the universal Absolute reality form without attributes).[29] In Tamil Shaiva tradition, for example, the common term for lingam is kuRi or "sign, mark" which is nonsexual.[29] Similarly, in Lingayatism tradition, the lingam is a spiritual symbol and "was never said to have any sexual connotations", according to Doniger.[31] To some Shaivites, it symbolizes the axis of the universe.[32]

Muslim rule

After the 11th-century invasion of the subcontinent by Islamic armies, the iconoclast Muslims considered the lingam to be idolatrous representations of the male sexual organ. They took pride in destroying as many lingams and Shiva temples as they could, reusing them to build steps for mosques, in a region stretching from Somanath (Gujarat) to Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh) to Chidambaram (Tamil Nadu), states Doniger.[31][33]

Orientalist literature

The colonial era Orientalists and Christian missionaries, raised in the Victorian mold where sex and sexual imagery were a taboo subject, were shocked by and were hostile to the lingam-yoni iconography and reverence they witnessed.[34][35] The 19th and early 20th-century colonial and missionary literature described yoni, lingam-yoni, and related theology as obscene, corrupt, licentious, hyper-sexualized, puerile, impure, demonic and a culture that had become too feminine and dissolute.[34][36][37] To the Hindus, particularly the Shaivites, these icons and ideas were the abstract, a symbol of the entirety of creation and spirituality.[34] The colonial disparagement in part triggered the opposite reaction from Bengali nationalists, who more explicitly valorised the feminine. Vivekananda called for the revival of the Mother Goddess as a feminine force, inviting his countrymen to "proclaim her to all the world with the voice of peace and benediction".[36]

According to Wendy Doniger, the terms lingam and yoni became explicitly associated with human sexual organs in the western imagination after the widely popular first Kamasutra translation by Sir Richard Burton in 1883.[38] In his translation, even though the original Sanskrit text does not use the words lingam or yoni for sexual organs, and almost always uses other terms, Burton adroitly avoided been viewed as obscene to the Victorian mindset by avoiding the use of words such as penis, vulva, vagina and other direct or indirect sexual terms in the Sanskrit text to discuss sex, sexual relationships and human sexual positions. Burton used the terms lingam and yoni instead throughout the translation.[38] This conscious and incorrect word substitution, states Doniger, thus served as an Orientalist means to "anthropologize sex, distance it, make it safe for English readers by assuring them, or pretending to assure them, that the text was not about real sexual organs, their sexual organs, but merely about the appendages of weird, dark people far away."[38] Similar Orientalist literature of the Christian missionaries and the British era, states Doniger, stripped all spiritual meanings and insisted on the Victorian vulgar interpretation only, which had "a negative effect on the self-perception that Hindus had of their own bodies" and they became "ashamed of the more sensual aspects of their own religious literature".[39] Some contemporary Hindus, states Doniger, in their passion to spiritualize Hinduism and for their Hindutva campaign have sought to sanitize the historic earthly sexual meanings, and insist on the abstract spiritual meaning only.[39]

Anthropologist Christopher John Fuller states that although most sculpted images (murtis) are anthropomorphic, the aniconic Shiva Linga is an important exception.[40]

Historical period

According to Shaiva Siddhanta, the linga is the ideal substrate in which the worshipper should install and worship the five-faced and ten-armed Sadāśiva, the form of Shiva who is the focal divinity of that school of Shaivism.[41]

Literature

- रुद्रो लिङ्गमुमा पीठं तस्मै तस्यै नमो नमः । सर्वदेवात्मकं रुद्रं नमस्कुर्यात्पृथक्पृथक् ॥ Rudrahridaya Upanishad 23rd verse

Meaning: Rudra is meaning. Uma is word. Prostrations to Him and Her. Rudra is Linga. Uma is Pitha. Prostrations to Him and Her.[42][43][44]

- पिण्डब्रह्माण्डयोरैक्यं लिङ्गसूत्रात्मनोरपि । स्वापाव्याकृतयोरैक्यं स्वप्रकाशचिदात्मनोः ॥ Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad 1.81

Meaning: The microcosm and the macrocosm are one and the same; so also the Linga and Sutratman, Svabhava (substance) and form and the self-resplendent light and Chidatma.[45][43][46]

- निधनपतयेनमः । निधनपतान्तिकाय नमः । ऊर्ध्वाय नमः । ऊर्ध्वलिङ्गाय नमः । हिरण्याय नमः । हिरण्यलिङ्गाय नमः । सुवर्णाय नमः ।सुवर्णलिङ्गाय नमः । दिव्याय नमः । दिव्यलिङ्गाय नमः । भवाय नमः। भवलिङ्गाय नमः । शर्वाय नमः । शर्वलिङ्गाय नमः । शिवाय नमः । शिवलिङ्गाय नमः । ज्वलाय नमः । ज्वललिङ्गाय नमः । आत्माय नमः । आत्मलिङ्गाय नमः । परमाय नमः । परमलिङ्गाय नमः ॥ Mahanarayana Upanishad 16.1

Meaning: By these twenty-two names ending with salutations they consecrate the Sivalinga for all – the Linga which is representative of soma and Surya, and holding which in the hand holy formulas are repeated and which purifies all.[47][48][49]

- तांश्चतुर्धा संपूज्य तथा ब्रह्माणमेव विष्णुमेव रुद्रमेव विभक्तांस्त्रीनेवाविभक्तांस्त्रीनेव लिङ्गरूपनेव च संपूज्योपहारैश्चतुर्धाथ लिङ्गात्संहृत्य ॥ Nrisimha Tapaniya Upanishad Chapter 3

Meaning: Thus after worshipping with nectar (Ananda Amrutha) the four fold Brahmas (Devatha, Teacher, Mantra and the soul), Vishnu, Rudra separately and then together in the form of Linga with offerings and then unifying the linga forms in the Atma Jyothi (Light of the soul) [50][51][52]

- तत्र द्वादशादित्या एकादश रुद्रा अष्टौ वसवः सप्त मुनयो ब्रह्मा नारदश्च पञ्च विनायका वीरेश्वरो रुद्रेश्वरोऽम्बिकेश्वरो गणेश्वरो नीलकण्ठेश्वरो विश्वेश्वरो गोपालेश्वरो भद्रेश्वर इत्यष्टावन्यानि लिङ्गानि चतुर्विंशतिर्भवन्ति ॥ Gopala Tapani Upanishad 41st verse

Meaning: The twelve Adityas, eleven Rudras, eight Vasus, seven sages, Brahma, Narada, five Vinayakas, Viresvara, Rudresvara, Ambikesvara, Ganesvara, Nilakanthesvara, Visvesvara, Gopalesvara, Bhadresvara, and 24 other lingas reside there[53][54][55]

- तन्मध्ये प्रोच्यते योनिः कामाख्या सिद्धवन्दिता । योनिमध्ये स्थितं लिङ्गं पश्चिमाभिमुखं तथा ॥ Dhyanabindu Upanishad 45th verse

Meaning: The midst of the Yoni is the Linga facing the west and split at its head like the gem. He who knows this, is a knower of the Vedas.[56][57][58]

- मात्रालिङ्गपदं त्यक्त्वा शब्दव्यञ्जनवर्जितम् । अस्वरेण मकारेण पदं सूक्ष्मं च गच्छति ॥ Amritabindu Upanishad 4th verse

Meaning: Having given up Matra, Linga and Pada, he attains the subtle Pada (seat or word) without vowels or consonants by means of the letter ‘M’ without the Svara (accent).[59][60][61]

- There is a repeated mention of lingam in the Tirumantiram, a Tamil scripture. Some verse:[62]

- Jiva is Sivalinga; The deceptive senses but the lights that illume. Tirumantiram 1823

- His Form as Uncreated Siva Linga His Form as Sadasiva Divine. Tirumantiram 1750

- Lingashtakam Strotram,[63] and Marga Sahaya Linga Sthuthi[64] are praising and asking for blessing from Lord Shiva in form of lingam

- Whatever the merit in any sacrifice, austerity, offering, pilgrimage or place, the merit of worship of the Shivalinga equals that merit multiplied by hundreds of thousands. Karana agama 9. MT, 66[65]

Naturally occurring lingams

An ice lingam at Amarnath in the western Himalayas forms every winter from ice dripping on the floor of a cave and freezing like a stalagmite. It is very popular with pilgrims.[66]

In Kadavul Temple, a 700-pound, 3-foot-tall, naturally formed Spatika(quartz) lingam is installed. In future this crystal lingam will be housed in the Iraivan Temple. it is claimed as among the largest known spatika self formed (Swayambhu) lingams.[67][68] Hindu scripture rates crystal as the highest form of Siva lingam.[69]

Shivling, 6,543 metres (21,467 ft), is a mountain in Uttarakhand (the Garhwal region of Himalayas). It arises as a sheer pyramid above the snout of the Gangotri Glacier. The mountain resembles a Shiva lingam when viewed from certain angles, especially when travelling or trekking from Gangotri to Gomukh as part of a traditional Hindu pilgrimage.

A lingam is also the basis for the formation legend (and name) of the Borra Caves in Andhra Pradesh.

Banalinga are the lingam which are found on the bed of the Narmada river.

Bhuteshwar shivling is a natural rock shivling in Chhattisgarh whose height is increasing with each passing year.[70][71] Sidheshvar Nath Temple's shivling is also a natural rock lingam in Arunachal Pradesh. It is believed to be the tallest natural lingam.

Lingam with carving

Mukhalinga is a lingam with one or more faces of Lord Shiva carved on it. They have generally have one, four or five faces.[72][73]

In Lingodbhava lingam, Lord Shiva's image is carved on the lingam which describes tale of Lingodbhavata where Vishnu and Brahma try to find start and end of the lingam[74][75]

Interpretations

Many describe the lingam as a phallic symbol, such as Varadaraja V. Raman (who argues that many devouts do not see it as such any longer)[76] and S. N. Balagangadhara.[77] Among the deniers of this theory are Swami Vivekananda[78] and Swami Sivananda (who considers the interpretation to be a mistake).[27]

Gallery

-

A 10th-century four-headed stone lingam (Mukhalinga) from Nepal

-

Gupta era one-faced Mukhalinga

-

Lingam-yoni at the Cát Tiên sanctuary, Lâm Đồng province, Vietnam

-

A jatalinga with yoni

-

Lingodbhava shivaling at British museum

See also

References

- ^ Johnson, W.J. (2009). A dictionary of Hinduism (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191726705. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)(subscription or UK public library membership required) - ^ Fowler, Jeaneane (1997). Hinduism : beliefs and practices. Brighton [u.a.]: Sussex Acad. Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9781898723608.

- ^ Balfour, Edward "Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia" Vol. 3 pg. 482

- ^ Dancing with Siva. USA. 1999. search:- "pīṭha: पीठ". ISBN 9780945497943.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dalal 2010, p. 208-209.

- ^ Olson 2007, p. 239–240.

- ^ a b "lingam". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010.

- ^ sivaya subramuniyaswami (2001). Dancing with Siva. USA: Himalayan Academy. ISBN 0945497970.

- ^ sivaya subramuniyaswami (2001). Dancing with Siva. USA: Himalayan Academy. ISBN 0945497970.

- ^ "Dictionary of Dancing with Siva". Search for the 'Paraśiva: परशिव' and 'Parāśakti: पराशक्ति'.

- ^ a b Singh, Nagendra Kr. (1997). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism (1st ed.). New Delhi: Centre for International Religious Studies. p. 1567. ISBN 9788174881687.

- ^ Lipner, Julius J. (2017). Hindu Images and Their Worship with Special Reference to Vaisnavism: A Philosophical-theological Inquiry. London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 39. ISBN 9781351967822. OCLC 985345208.

- ^ a b c d e f Asko Parpola (1985). "The Sky Garment - A study of the Harappan religion and its relation to the Mesopotamian and later Indian religions". Studia Orientalia. 57. The Finnish Oriental Society: 101–107.

- ^ Arthur Llewellyn Basham (1967). The Wonder that was India: A Survey of the History and Culture of the Indian Subcontinent Before the Coming of the Muslims. Sidgwick & Jackson (1986 Reprint). p. 24. ISBN 978-0-283-99257-5., Quote: "It has been suggested that certain large ring-shaped stones are formalized representations of the female regenerative organ and were symbols of the Mother Goddess, but this is most doubtful."

- ^ Constance Jones, James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 516.

- ^ Jyotsna Chawla. The R̥gvedic deities and their iconic forms. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 185.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 485–502. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 489–502. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ a b c Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). "God, the Father". Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-81-208-1450-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Vivekananda, Swami. "The Paris Congress of the History of Religions". The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol. Vol.4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 491–493. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007). A Survey of Hinduism (3. ed.). Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4.

- ^ Elgood, Heather (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. London: Cassell. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8264-9865-6.

- ^ Alf Hiltebeitel (2018). Freud's Mahabharata. Oxford University Press. pp. 123–124, footnote 179. ISBN 978-0-19-087834-4.

- ^ Chaturvedi. Shiv Purana (2006 ed.). Diamond Pocket Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-7182-721-3.

- ^ a b c Blurton, T. R. (1992). "Stone statue of Shiva as Lingodbhava". Extract from Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press). British Museum site. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ a b Sivananda, Swami (1996). "Worship of Siva Linga". Lord Siva and His Worship. The Divine Life Trust Society.

- ^ "Reading the Vedic Literature in Sanskrit". is1.mum.edu. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 493–498. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ J. L. Brockington (2016). Hinduism and Christianity. Springer. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-349-22280-3.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 498–499. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ Susan Bayly (2003). Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–130 with footnote 55. ISBN 978-0-521-89103-5.

- ^ Mehrdad Shokoohy (2013). Muslim Architecture of South India. Routledge. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-136-49984-5.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

dasgupta107was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Douglas T. McGetchin (2009). Indology, Indomania, and Orientalism: Ancient India's Rebirth in Modern Germany. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8386-4208-5.

- ^ a b Imma Ramos (2017). Pilgrimage and Politics in Colonial Bengal: The Myth of the Goddess Sati. Taylor & Francis. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-351-84000-2.

- ^ Hugh B. Urban (2009). The Power of Tantra: Religion, Sexuality and the Politics of South Asian Studies. I.B.Tauris. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0-85773-158-6.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 500–502. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 499–505. JSTOR 23347187.

- ^ The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and society in India, pg. 58 at Books.Google.com

- ^ Dominic Goodall, Nibedita Rout, R. Sathyanarayanan, S.A.S. Sarma, T. Ganesan and S. Sambandhasivacarya, The Pañcāvaraṇastava of Aghoraśivācārya: A twelfth-century South Indian prescription for the visualisation of Sadāśiva and his retinue, Pondicherry, French Institute of Pondicherry and Ecole française d'Extréme-Orient, 2005, p.12.

- ^ "Translation of Rudrahridya".

- ^ a b "Glory to lord Bhuvaneshwar".

- ^ "Sanskrit verses Rudrahridaya" (PDF). page 2.

- ^ "Translation of Yoga kundalini". verse 81.

- ^ "Sanskrit verse of Yoga kundalini Upanishad".

- ^ "translation of Maha Narayana upniahad".

- ^ "Maha Naryana upanishad".

- ^ "Sanskrit verse of Maha Vishnu Upanishad" (PDF). Page 17.

- ^ "nrisimha-tapaniya sanskrit".

- ^ "nrisimha-tapaniya english translation". Archived from the original on 27 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "/nrisimha-tapaniya english".

- ^ "gopala-tapaniya sanskrit".

- ^ "gopala-tapaniya english".

- ^ "gopala-tapaniya english translation". Archived from the original on 1 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "dhyana-bindu sanskrit".

- ^ "dhyana-bindu english translation".

- ^ "dhyana-bindu english transalation". Archived from the original on 27 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "amrita-nada sanskrit".

- ^ "amrita-nada english".

- ^ "mritanada english translation". Archived from the original on 27 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tirumantiram" (PDF). page 422 and 407 respectively.

- ^ "Jyotir Linga Stotram". Archived from the original on 29 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Marga Sahaya Linga Sthuthi". Archived from the original on 9 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Karana Agama".

- ^ "Amarnath: Journey to the shrine of a Hindu god". 13 July 2012.

- ^ under the section "GENERAL INTRODUCTION". "Kadavul Hindu Temple". Himalayanacademy.

- ^ "Iraivan Temple In the News".

- ^ "Rare Crystal Siva Lingam Arrives At Hawaii Temple". hinduismtoday.

- ^ "Bhuteshwar Shivling". news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Shivling in Chhattisgarh".

- ^ Andrew David Hardy; Mauro Cucarzi; Patrizia Zolese (2009). Champa and the Archaeology of Mỹ Sơn (Vietnam). p. NUS Press. pp. 138, 159. ISBN 978-9971-69-451-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pratapaditya Pal. Art of Nepal: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. University of California Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-520-05407-3.

- ^ "Lingodbhava - Origin of Shiva Linga Worship".

- ^ "Lingodbhava".

- ^ Raman Varadara, Raman Varadara Staff (1993). Glimpses of Indian Heritage. Popular Prakashan. p. 102.

- ^ Balagangadhara, S.N; Claerhout, Sarah (2008). "Are Dialogues Antidotes to Violence? Two Recent Examples from Hinduism Studies" (PDF). Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies. 7 (9): 118–143.

- ^ Vivekananda, Swami. "The Paris Congress of the History of Religions". The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol. Vol.4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

Sources

- Basham, A. L. The Wonder That Was India: A survey of the culture of the Indian Sub-Continent before the coming of the Muslims, Grove Press, Inc., New York (1954; Evergreen Edition 1959).

- Schumacher, Stephan and Woerner, Gert. The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion, Buddhism, Taoism, Zen, Hinduism, Shambhala, Boston, (1994) ISBN 0-87773-980-3.

- Chakravarti, Mahadev. The Concept of Rudra-Śiva Through the Ages, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass (1986), ISBN 8120800532.

- Davis, Richard H. (1992). Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Śiva in Medieval India. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691073866.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Dalal, Roshen (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Drabu, V.N. Śaivāgamas: A Study in the Socio-economic Ideas and Institutions of Kashmir (200 B.C. to A.D. 700), New Delhi: Indus Publishing (1990), ISBN 8185182388.

- McCormack, William (1963), "Lingayats as a Sect", The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 93 (1): 59–71, doi:10.2307/2844333

- Olson, Carl (2007), The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-historical Introduction, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0813540689

- Ram Karan Sharma. Śivasahasranāmāṣṭakam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Śiva. With Introduction and Śivasahasranāmākoṣa (A Dictionary of Names). (Nag Publishers: Delhi, 1996). ISBN 81-7081-350-6. This work compares eight versions of the Śivasahasranāmāstotra. The preface and introduction Template:En icon by Ram Karan Sharma provide an analysis of how the eight versions compare with one another. The text of the eight versions is given in Sanskrit.

- Kramrisch, Stella (1988). The Presence of Siva. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804913.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Daniélou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. pp. 222–231. ISBN 0-89281-354-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Versluis, Arthur (2008), The Secret History of Western Sexual Mysticism: Sacred Practices and Spiritual Marriage, Destiny Books, ISBN 978-1-59477-212-2

![Lingodbhava Shiva with Vishnu as Varaha and Brahma as Hamsa[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Lingodbhava_Shiva.jpg/83px-Lingodbhava_Shiva.jpg)