Jurassic: Difference between revisions

Hemiauchenia (talk | contribs) |

Hemiauchenia (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 295: | Line 295: | ||

==== Actinopterygii ==== |

==== Actinopterygii ==== |

||

[[Amiiformes|Amiiform]] fish (which today only includes the living [[bowfin]]) would first appear during the Early Jurassic, represented by ''[[Caturus]]'' from the Pliensbachian of Britain, after their first appearance in western Tethys, they would expand to Africa, North America and Southeast and East Asia by the end of the Jurassic. [[Pycnodontiformes]], which first appeared in the western Tethys during the Late Triassic, would expand to South America and Southeast Asia by the end of the Jurassic, having a high diversity in Europe during the Late Jurassic.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Poyato-Ariza|first=Francisco José|last2=Martín-Abad|first2=Hugo|date=2020-07-19|title=History of two lineages: Comparative analysis of the fossil record in Amiiformes and Pycnodontiformes (Osteischtyes, Actinopterygii)|url=https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/sjpalaeontology/article/view/17833|journal=Spanish Journal of Palaeontology|volume=28|issue=1|pages=79|doi=10.7203/sjp.28.1.17833|issn=2255-0550}}</ref> |

Bony fish ([[Actinopterygii]]) were major components of Jurassic freshwater and marine ecosystems. [[Amiiformes|Amiiform]] fish (which today only includes the living [[bowfin]]) would first appear during the Early Jurassic, represented by ''[[Caturus]]'' from the Pliensbachian of Britain, after their first appearance in western Tethys, they would expand to Africa, North America and Southeast and East Asia by the end of the Jurassic. [[Pycnodontiformes]], which first appeared in the western Tethys during the Late Triassic, would expand to South America and Southeast Asia by the end of the Jurassic, having a high diversity in Europe during the Late Jurassic.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Poyato-Ariza|first=Francisco José|last2=Martín-Abad|first2=Hugo|date=2020-07-19|title=History of two lineages: Comparative analysis of the fossil record in Amiiformes and Pycnodontiformes (Osteischtyes, Actinopterygii)|url=https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/sjpalaeontology/article/view/17833|journal=Spanish Journal of Palaeontology|volume=28|issue=1|pages=79|doi=10.7203/sjp.28.1.17833|issn=2255-0550}}</ref> [[Teleost|Teleosts]], which make up over 99% of living Actinopterygii, had first appeared during the Triassic in the western Tethys, underwent a major diversification beginning in the Late Jurassic, with early representatives of modern teleost clades such as [[Elopomorpha]] and [[Osteoglossoidei]] appearing during this time.<ref>Arratia G. Mesozoic halecostomes and the early radiation of teleosts. In: Arratia G, Tintori A, editors. Mesozoic Fishes 3 – Systematics, Paleoenvironments and Biodiversity. München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil; 2004. p. 279–315.</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Tse|first=Tze-Kei|last2=Pittman|first2=Michael|last3=Chang|first3=Mee-mann|date=2015-03-26|title=A specimen of Paralycoptera Chang & Chou 1977 (Teleostei: Osteoglossoidei) from Hong Kong (China) with a potential Late Jurassic age that extends the temporal and geographical range of the genus|url=https://peerj.com/articles/865|journal=PeerJ|language=en|volume=3|pages=e865|doi=10.7717/peerj.865|issn=2167-8359}}</ref> The [[Pachycormiformes]], a group of fish closely allied to teleosts, would first appear in the Early Jurassic, and included both [[tuna]]-like predatory and filter feeding forms, the latter including the largest bony fish known to have existed, ''[[Leedsichthys]]'', with an estimated maximum length of over 15 metres, known from the late Middle to Late Jurassic.<ref name="Liston2013">Liston, J., Newbrey, M., Challands, T., and Adams, C., 2013, "Growth, age and size of the Jurassic pachycormid ''Leedsichthys problematicus'' (Osteichthyes: Actinopterygii) in: Arratia, G., Schultze, H. and Wilson, M. (eds.) ''Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution''. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, Germany, pp. 145–175</ref> |

||

==== Chondrichthyes ==== |

==== Chondrichthyes ==== |

||

Revision as of 21:27, 31 December 2020

| Jurassic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronology | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Etymology | |||||||||

| Name formality | Formal | ||||||||

| Usage information | |||||||||

| Celestial body | Earth | ||||||||

| Regional usage | Global (ICS) | ||||||||

| Time scale(s) used | ICS Time Scale | ||||||||

| Definition | |||||||||

| Chronological unit | Period | ||||||||

| Stratigraphic unit | System | ||||||||

| Time span formality | Formal | ||||||||

| Lower boundary definition | First appearance of the Ammonite Psiloceras spelae tirolicum. | ||||||||

| Lower boundary GSSP | Kuhjoch section, Karwendel mountains, Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria 47°29′02″N 11°31′50″E / 47.4839°N 11.5306°E | ||||||||

| Lower GSSP ratified | 2010 | ||||||||

| Upper boundary definition | Not formally defined | ||||||||

| Upper boundary definition candidates |

| ||||||||

| Upper boundary GSSP candidate section(s) | None | ||||||||

| Atmospheric and climatic data | |||||||||

| Mean atmospheric O2 content | c. 26 vol % (125 % of modern) | ||||||||

| Mean atmospheric CO2 content | c. 1950 ppm (7 times pre-industrial) | ||||||||

| Mean surface temperature | c. 16.5 °C (3 °C above pre-industrial) | ||||||||

The Jurassic (/dʒʊˈræs.sɪk/ juu-RASS-ik;[2]) is a geologic period and system that spanned 56 million years from the end of the Triassic Period 201.4 million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period 145 Mya.[note 1] The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of the Mesozoic Era. The Jurassic is named after the Jura Mountains in the European Alps, where limestone strata from the period were first identified.

The start of the period was marked by the major Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. Two other extinction events occurred during the period: the Pliensbachian-Toarcian extinction in the Early Jurassic, and the Tithonian event at the end;[5] neither event ranks among the "Big Five" mass extinctions, however.

The Jurassic period is divided into three epochs: Early, Middle, and Late. Similarly, in stratigraphy, the Jurassic is divided into the Lower Jurassic, Middle Jurassic, and Upper Jurassic series of rock formations.

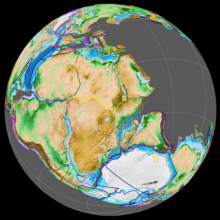

By the beginning of the Jurassic, the supercontinent Pangaea had begun rifting into two landmasses: Laurasia to the north, and Gondwana to the south. This created more coastlines and shifted the continental climate from dry to humid, and many of the arid deserts of the Triassic were replaced by lush rainforests.

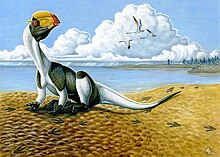

On land, the fauna transitioned from the Triassic fauna, dominated by both dinosauromorph and crocodylomorph archosaurs, to one dominated by dinosaurs alone. The first birds also appeared during the Jurassic, having evolved from a branch of theropod dinosaurs. Other major events include the appearance of the earliest lizards, and the evolution of therian mammals. Crocodilians made the transition from a terrestrial to an aquatic mode of life. The oceans were inhabited by marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, while pterosaurs were the dominant flying vertebrates.

Etymology and history

The chronostratigraphic term "Jurassic" is directly linked to the Jura Mountains, a mountain range mainly following the course of the France–Switzerland border. The name "Jura" is derived from the Celtic root *jor via Gaulish *iuris "wooded mountain", which, borrowed into Latin as a place name, evolved into Juria and finally Jura.[6][7][8] During a tour of the region in 1795,[note 2] Alexander von Humboldt recognized the mainly limestone dominated mountain range of the Jura Mountains as a separate formation that had not been included in the established stratigraphic system defined by Abraham Gottlob Werner, and he named it "Jura-Kalkstein" ('Jura limestone') in 1799.[note 3][6][7][11]

Thirty years later, in 1829, the French naturalist Alexandre Brongniart published a survey on the different terrains that constitute the crust of the Earth. In this book, Brongniart referred to the terrains of the Jura Mountains as terrains jurassiques, thus coining and publishing the term for the first time.[12] The German geologist Leopold von Buch in 1839 established the three-fold division of the Jurassic, originally named from oldest to youngest, the Black Jurassic, Brown Jurassic and White Jurassic.[13] The term "Lias" had previously been used equivalently for strata of equivalent age to the Black Jurassic in England by Conybeare and Phillips in 1822. French palaeontologist Alcide d'Orbigny in papers between 1842 and 1852 would divide the Jurassic into ten stages “étages” based on ammonite and other fossil assemblages in England and France, of which seven are still used, though none retain the original definition. German geologist and palaeontologist Friedrich August von Quenstedt in 1858 would divide the three series of von Buch in the Swabian Jura into six subdivisions defined by ammonites and other fossils. German palaeontologist Albert Oppel in studies between 1856 and 1858 altered d'Orbigny's original scheme and further subdivided the stages into biostratigraphic zones, based primarily on ammonites. Most of the modern stages of the Jurassic were formalized at the "Colloque du Jurassique á Luxembourg" in 1962.[14]

Geology

The Jurassic period is divided into three epochs: Early, Middle, and Late. Similarly, in stratigraphy, the Jurassic is divided into the Lower Jurassic, Middle Jurassic, and Upper Jurassic series of rock formations, also known in Europe as Lias, Dogger and Malm.[15] The three epochs are subdivided into shorter spans of time called ages. The ages of the Jurassic from youngest to oldest are:

| Upper/Late Jurassic | Tithonian | (149.2 ± 0.9 – 145 Mya) |

| Kimmeridgian | (154.8 ± 1.0 – 149.2 ± 0.9 Mya) | |

| Oxfordian | (161.5 ± 1.0 – 154.8 ± 1.0 Mya) | |

| Middle Jurassic | Callovian | (165.3 ± 1.2 – 161.5 ± 1.0 Mya) |

| Bathonian | (168.2 ± 1.3 – 165.3 ± 1.2 Mya) | |

| Bajocian | (170.9 ± 1.4 – 168.2 ± 1.3 Mya) | |

| Aalenian | (174.7 ± 1.0 – 170.9 ± 1.4 Mya) | |

| Lower/Early Jurassic | Toarcian | (184.2 ± 0.7 – 174.7 ± 1.0 Mya) |

| Pliensbachian | (192.9 ± 1.0 – 184.2 ± 0.7 Mya) | |

| Sinemurian | (199.5 ± 0.3 – 192.9 ± 1.0 Mya) | |

| Hettangian | (201.4 ± 0.2 – 199.5 ± 0.3 Mya) |

Stratigraphy

Jurassic stratigraphy is primarily based around of the use of ammonites as index fossils, with the First Appearance Datum of specific ammonite taxa being used to mark the beginnings of stages, and well as smaller timespans within stages, referred to as "Ammonite Zones", these in turn are also sometimes subdivided further into subzones. Global stratigraphy is based on standard European ammonite zones, with other regions being calibrated to the European successions.[14]

The oldest part of the Jurassic period has historically been referred to as the Lias or Liassic, roughly equivalent in extent to the Early Jurassic, but also including part of the preceding Rhaetian. The Hettangian stage was named by Swiss palaeontologist Eugène Renevier in 1864 after Hettange-Grande in North-Eastern France. The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Hettangian is located at Kuhjoch pass, Karwendel Mountains, Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria, which was ratified in 2010. The beginning of the Hettangian, and thus the Jurassic as a whole, is marked by the first appearance of the ammonite Psiloceras spelae tirolicum.[16] The base of the Jurassic was previously defined as the first appearance of Psiloceras planorbis by Albert Oppel in 1856-58, but this was changed as the appearance was seen as too localised an event for an international boundary.[14]

The Sinemurian stage was defined and introduced into scientific literature by Alcide d'Orbigny in 1842. It takes its name from the French town of Semur-en-Auxois, near Dijon. The original definition of Sinemurian included what is now the Hettangian. The GSSP of the Sinemurian is located at a cliff face north of the hamlet of East Quantoxhead, 6 kilometres east of Watchet, Somerset, England, within the Blue Lias. The beginning of the Sinemurian is defined by the first appearance of the ammonite Vermiceras quantoxense.[14][17]

The Pliensbachian was named by German palaeontologist Albert Oppel in 1858 after the hamlet of Pliensbach in the community of Zell unter Aichelberg in the Swabian Alb, near Stuttgart, Germany. The GSSP for the base of the Pliensbachian is found at the Wine Haven locality in Robin Hood's Bay, Yorkshire, England, in the Redcar Mudstone Formation. The beginning of the Pliensbachian is defined by the first appearance of the ammonite Bifericeras donovani.[18]

The Toarcian is named after the village Thouars (Latin: Toarcium), just south of Saumur in the Loire Valley of France, it was defined by Alcide d'Orbigny in 1842 originally from Vrines quarry around 2 km northwest of the village. The GSSP for the base of the Toarcian is located at Peniche, Portugal. The boundary is defined by the first appearance of ammonites belonging to the subgenus Dactylioceras (Eodactylioceras).[19]

The Aalenian is named after the city of Aalen in Germany. The Aalenian was defined by Swiss geologist Karl Mayer-Eymar in 1864. The lower boundary was originally between the dark clays of the Black Jurassic and the overlying clayey sandstone and ferruginous oolite of the Brown Jurassic sequences of southwestern Germany.[14] The GSSP for the base of the Aalenian is located at Fuentelsaz in the Iberian range near Guadalajara, Spain. The base of the Aalenian is defined by the first appearance of the ammonite Leioceras opalinum.[20]

The Bajocian is named after the town of Bayeux (Latin: Bajoce) in Normandy, France, and was defined by Alcide d'Orbigny in 1842. The GSSP for the base of the Bajocian is located at Murtinheira in Portugal, and was defined in 1997. The base of the Bajocian is defined by the first appearance of the ammonite Hyperlioceras mundum.[21]

The Bathonian is named after the city of Bath, England, introduced by Belgian geologist d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1843, after an incomplete section of oolitic limestones in several quarries in the region. The GSSP for the base of the Bathonian is Ravin du Bès, Bas-Auran area, Alpes de Haute Provence, France, which was defined in 2009. The base of the Bathonian is defined by the first appearance of the ammonite Gonolkites convergens, at the base of the Zigzagiceras zigzag ammonite zone.[22]

The Callovian is derived from the latinized name of the village of Kellaways in Wiltshire, England, and was defined by Alcide d'Orbigny in 1852, originally with base at the contact between the Forest Marble Formation and the Cornbrash Formation. However, this boundary was later found to be situated within the upper part of the Bathonian. The base of the Callovian does not yet have a certified GSSP, as of 2019.[14]

The Oxfordian is named after the city of Oxford in England, and was named by Alcide d'Orbigny in 1844 in reference to the Oxford Clay. The base of the Oxfordian lacks a defined GSSP. W. J. Arkell in studies in 1939 and 1946 placed the lower boundary of the Oxfordian as the first appearance of the ammonite Quenstedtoceras mariae (then placed in the genus Vertumniceras). Subsequent proposals have suggested the first appearance of Cardioceras redcliffense as the lower boundary.[14]

The Kimmeridgian is named after the village of Kimmeridge on the coast of Dorset, England. It was named by Alcide d'Orbigny in 1842, in reference to the Kimmeridge Clay. Although not confirmed, the Flodigarry section at Staffin Bay on the Isle of Skye, Scotland has been submitted as the GSSP for the base of the Kimmeridgian.[23]

The Tithonian was introduced in scientific literature by Albert Oppel in 1865. The name Tithonian is unusual in geological stage names because it is derived from Greek mythology rather than a placename. Tithonus was the son of Laomedon of Troy and fell in love with Eos, the Greek goddess of dawn. His name was chosen by Albert Oppel for this stratigraphical stage because the Tithonian finds itself hand in hand with the dawn of the Cretaceous. The base of the Tithonian currently lacks a GSSP.[14] The upper boundary of the Jurassic is also currently undefined. Calpionellids, an enigmatic group of pelagic protists with urn shaped calcitic tests briefly abundant during the latest Jurassic to earliest Cretaceous, have been suggested to represent the most promising candidates for fixing the J/K boundary.[24]

Mineral and Hydrocarbon deposits

The Kimmeridge Clay and equivalents are the major source rock for the North Sea oil.[25] The Arabian Intrashelf Basin, deposited from the late Middle to Upper Jurassic, is the setting of the worlds largest oil reserves, including the Ghawar Field, the world largest oil field.[26] The Jurassic aged Sargelu[27] and Naokelekan Formations[28] are major source rocks for oil in Iraq. Over 1500 gigatons of Jurassic coal reserves are found in North-West China, primarily in the Turpan-Hami Basin and the Ordos Basin.[29]

Impact craters

Major impact craters include the Morokweng crater, a 70 km diameter crater buried beneath the Kalahari desert in northern South Africa. The impact is dated to the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary, around 145 Ma. The Morokweng crater has been suggested to have had a role in the turnover at the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition.[30] Another major impact crater is the Puchezh-Katunki crater, 40-80 kilometres in diameter, buried beneath Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia. The impact has been dated to the Sinemurian, around 192-196 Mya.[31]

Paleogeography and tectonics

During the early Jurassic period, the supercontinent Pangaea broke up into the northern supercontinent Laurasia and the southern supercontinent Gondwana; the Gulf of Mexico opened in the new rift between North America and what is now Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. The Jurassic North Atlantic Ocean was relatively narrow, while the South Atlantic did not open until the following Cretaceous period.[32] The continents were surrounded by Panthalassa, with the Tethys Ocean between Gondwana and Asia. At the end of the Triassic, there was a marine transgression in Europe, flooding most parts of central and western Europe transforming it into an archipelago of islands surrounded by shallow seas.[33] The arctic arm of Panthalassa was connected to the western Tethys by the "Viking corridor", a several hundred kilometer wide passage between the Baltic Shield and Greenland.[34] Madagascar and Antarctica began to rift away from Africa during Early Jurassic, beginning the fragmentation of Gondwana.[35][36] During the Early Jurassic, around 190 million years ago, the Pacific Plate originated at the triple junction of the Farallon, Phoenix, and Izanagi plates, the three main oceanic plates of Panthalassa. The previously stable triple junction had converted to an unstable arrangement surrounded on all sides by transform faults, due to a kink in one of the plate boundaries, resulting in the formation of the Pacific Plate at the centre of the junction, which began to expand.[37] Climates were warm, with no evidence of a glacier having appeared. As in the Triassic, there was apparently no land over either pole, and no extensive ice caps existed. During the Middle to early Late Jurassic, the Sundance Seaway, a shallow epicontinental sea would cover much of northwest North America.[38]

Based on estimated sea level curves, the sea level was close to present levels during the Hettangian and Sinemurian, rising several tens of metres during the late Sinemurian-Pliensbachian, before regressing to near present levels by the late Pliensbachian. There seems to have been a gradual rise to a peak of ~75 m above present sea level during the Toarcian. During the latest part of the Toacian, the sea level again drops by several tens of metres. The sea level progressively rose from the Aalenian onwards, aside from dips of a few tens of metres in the Bajocian and around the Callovian-Oxfordian boundary, culminating in a sea level possibly as high as 140 metres above present sea level at the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian boundary. The sea levels falls in the Late Tithonian, perhaps to around 100 metres, before rebounding to around 110 metres at the Tithonian-Berriasian boundary. Sea level within the long term trend was cyclical with 64 fluctuations through the Jurassic, 15 of which were over 75 metres. The most noted cyclicity in Jurassic rocks is fourth order, with a periodicity of approximately 410,000 years.[39]

The Jurassic was a time of calcite sea geochemistry in which low-magnesium calcite was the primary inorganic marine precipitate of calcium carbonate. Carbonate hardgrounds were thus very common, along with calcitic ooids, calcitic cements, and invertebrate faunas with dominantly calcitic skeletons.[40]

The first of several massive batholiths were emplaced in the northern American cordillera beginning in the mid-Jurassic, marking the Nevadan orogeny.[41]

In Africa, Early Jurassic strata are distributed in a similar fashion to Late Triassic beds, with more common outcrops in the south and less common fossil beds which are predominated by tracks to the north.[42] As the Jurassic proceeded, larger and more iconic groups of dinosaurs like sauropods and ornithopods proliferated in Africa.[42] Middle Jurassic strata are neither well represented nor well studied in Africa.[42] Late Jurassic strata are also poorly represented apart from the spectacular Tendaguru fauna in Tanzania.[42] The Late Jurassic life of Tendaguru is very similar to that found in western North America's Morrison Formation.[42]

-

Jurassic limestones and marls (the Matmor Formation) in southern Israel

-

The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation in Colorado is one of the most fertile sources of dinosaur fossils in North America

-

Gigandipus, a dinosaur footprint in the Lower Jurassic Moenave Formation at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm, southwestern Utah

-

The Permian through Jurassic stratigraphy of the Colorado Plateau area of southeastern Utah

Climatic events

Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event

The Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (TOAE) was an episode of widespread oceanic anoxia during the early part of the Toarcian period, c. 183 Mya. It is marked by a globally documented high amplitude negative carbon isotope excursion,[43] as well as the deposition of black shales, and the extinction and collapse of carbonate producing marine organisms. The cause is often linked to the eruption of the Karoo-Ferrar large igneous provinces and the associated increase of carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere and the possible associated release of methane clathrates. This likely accelerated the hydrological cycle and increased silicate weathering. Groups affected include ammonites, ostracods, forams, brachiopods, bivalves and cnidarians,[44][45] with the last two spire-bearing brachiopod orders Spiriferinida and Athyridida becoming extinct.[46] While the event had significant impact on marine invertebrates, it had little effect on marine reptiles.[47] During the TOAE, the Sichuan Basin was transformed into a giant lake, probably 3 times the size of Lake Superior, represented by the Da’anzhai Member of the Ziliujing Formation. The lake likely sequestered ∼460 Gigatons (Gt) of organic carbon and ∼1,200 Gt of inorganic carbon during the event.[48] During the event. seawater PH, which had already substantially decreased prior to the event, increased slightly during the early stages of the TOAE, before dropping to its lowest point around the middle of the event.[49] This ocean acidification is what likely caused the collapse of carbonate production.[50][51]

Flora

End Triassic Extinction

The preceding end-Triassic extinction would result in the decline of Peltaspermaceae seed ferns, with Lepidopteris perisisting into the Early Jurassic in Patagonia.[52] At the Triassic-Jurassic boundary in Greenland, the sporomorph diversity suggests a complete floral turnover.[53] An analysis of macrofossil floral communites in Europe suggests no extinction over the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, and that changes were mainly due to local ecological succession.[54] Dicroidium, a seed fern that was a dominant part of Gondwanan floral communities during the Triassic, would decline at the T-J, boundary, surviving as a relict in Antarctica into the Sinemurian.[55]

Floral composition

Flowering plants, which make up 90% of living plant species, have no records from the Jurassic, with no claim of Jurassic representatives of the group having gained widespread acceptance.[56]

Conifers

Trees of the Jurassic were dominated by conifers and modern conifier groups would diversify throughout the period.

Araucarian conifers were widespread across both hemispheres. The divergence between Araucaria and the branch containing Wollemia and Agathis is estimated to have taken place during the Mid-Jurassic, based on Araucaria mirabilis and Araucaria sphaerocarpa from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina and England respectively, which are early members of the Araucaria lineage. Representatives of Wollemia-Agathis lineage are not known until the Cretaceous.[57][58]

Also abundant during the Jurassic is the extinct family Cheirolepidiaceae, often recognised by their highly distinctive Classopolis pollen. Jurassic representatives include the pollen cone Classostrobus and the seed cone Pararaucaria. Both Araucarian and Cheirolepidiaceae confiers often occur in association.[59]

The oldest definitive record of the cypress family (Cupressaceae) is Austrohamia minuta from the Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian) of Patagonia, known from several elements.[60] Austrohamia is thought to have close affinities with Taiwania and Cunninghamia. By the Mid-Late Jurassic Cupressaceae were abundant in warm temperate-tropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere, most abundantly represented by the genus Elatides.[61] The seed cone Scitistrobus from the Middle Jurassic (Aalenian) of Scotland displays a mosaic of traits indicative of ancestral Voltziales and derived Cupressaceae.[62]

The oldest record of the pine family (Pinaceae) is the seed cone Eathiestrobus, known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) also of Scotland.[63] During the Early Jurassic, the flora of the mid-latitudes of Eastern Asia were dominated by the extinct decidous broad leafed conifer Podozamites, likely of voltzialean affinities, with its range extending northwards into polar latitudes of Siberia, but its range contracted northward in the Middle-Late Jurassic corresponding to the increasing aridity of the region.[64]

The earliest record of the yew family (Taxaceae) is Palaeotaxus rediviva, from the Hettangian of Sweden, suggested to be closely related to Austrotaxus, while Marskea jurassica from the Middle Jurassic of Yorkshire, England and material from the Callovian-Oxfordian Daohugou bed in China are thought to be closely related to Amentotaxus. The Daohugou material in particular is extremely similar to living Amentotaxus, only differing in having shorter seed-bearing axes.[65]

Podocarpaceae, today largely confined to the Southern Hemisphere occurs in the Northern Hemisphere during the Jurassic, including Podocarpophyllum from the Lower-Middle Jurassic of Central Asia and Siberia.[66] Scarburgia from the Middle Jurassic of Yorkshire,[67] and Harrisiocarpus from the Jurassic of Poland.[68]

Ginkgoales

Ginkgoales, which are currently represented by the single living species Ginkgo biloba, were more diverse during the Jurassic, they were among the most important components of Laurasian Jurassic floras, and were adapted to a wide variety of climatic conditions. Based on reproductive organs several lineages can be distinguished, including Yimaia, Grenana, Nagrenia and Karkenia, alongside Ginkgo. These lineages are assocated with leaf morphotaxa such as Baiera, Ginkgoites and Sphenobaiera, some of which overlap with the morphological variability and growth stages of living Ginkgo biloba leaves and therefore cannot be used for reliable taxonomic identification.[69][70] Umaltolepis, historically thought to be ginkgoalean, and Vladimaria from the Jurassic of Asia have strap shaped ginkgo-like leaves (Pseudotorellia), with highly distinct reproductive structures with similarities to those of peltasperm and corystosperm seed ferns, and have been placed in the separate order Vladimariales, which may belong to a broader Ginkgoopsida.[71]

Ferns

The ground cover was dominated by ferns, including members of the living families Dipteridaceae, Matoniaceae, Osmundaceae and Marattiaceae,[72] as well as horsetails. Polypodiales ferns, which today make up 80% of living fern diversity, have no record from the Jurassic, and are thought to have diversified in the Cretaceous,[73] though the widespread Jurassic herbaceous fern genus Coniopteris, historically interpreted as a close relative of tree ferns of the family Dicksoniaceae, has recently been reinterpreted as an early relative of the group.[74]

A calicfied rhizome of an Osmundaceous fern from the Early Jurassic of Sweden belongs to the stem group of the living genus Osmundastrum, with the preservation showing the remains of chromosomes during cell division.[75] An analysis of the Osmundastrum rhizome found that it had been interacted with by numerous organisms, including lycopsid roots growing into the rhizome, probable peronosporomycetes as well as boring and coprolites likely by orbatid mites.[76]

The oldest remains of modern horsetails of the genus Equisetum first appear in the Early Jurassic, represented by Equisetum dimorphum from the Early Jurassic of Patagonia[77] and Equisetum laterale from the Early-Middle Jurassic of Australia.[78][79] Silicified remains of Equisetum thermale from the Late Jurassic of Argentina exhibit all the morphological characters of modern members of the genus.[80] The estimated split between Equisetum bogotense and all other living Equisetum is estimated to have occcured no later than the Early Jurassic.[79]

The Cyatheales, the group containing most modern tree ferns would appear during the Late Jurassic, represented by members of the genus Cyathocaulis, which are suggested to be early members of Cyatheaceae based on cladistic analysis.[81] Only a handful of possible records exist of the Hymenophyllaceae are known from the Jurassic, including Hymenophyllites macrosporangiatus from the Russian Jurassic.[82]

Bennettitales

Bennettitales are a group of seed plants widespread throughout the Mesozoic with foliage bearing strong similarities to those of cycads, to the point of morphologically indistinguishable. Benettitales can be distinguished from cycads by the fact they have a different arrangement of stomata, and are not thought to be closely related.[83] Benettitales have morphologies varying from cycad-like to shubs and small trees. The Williamsoniaceae grouping is thought to have had a divaricate branching habit, similar to living Banksia, and adapted to growing in open habitats with poor soil nutrient conditions.[84] Benettitales exhibit complex, flower like reproductive structures that are thought to have been pollinated by insects. Several groups of insects that bear long proboscis, including extinct families like Kalligrammatid lacewings[85] and extant Acroceridae flies,[86] are suggested to have been pollinators of benettitales, feeding on nectar produced by bennettitalean cones.

Cycads

Cycads were present during the Jurassic, the living groups of cycads have been suggested to have diverged from each other in the Early Jurassic,[87] though a later analysis placed this divergence during the Late Permian, which placed the diversification of the Zamiineae cycads during the Jurassic.[88] Cycads are difficult to distinguish from Bennettitales based on leaf morphology alone. Cycads are thought to have been a relatively minor component of mid-Mesozoic floras.[89] and mostly confined to tropical and subtropical latitudes.[90] Cycad foliage is assigned to morphogenera including Ctenis and Pterophyllum, but are not phylogenetically informative. Seeds from the late Callovian-early Oxfordian Oxford Clay are definitively assignable to the living family Cycadaceae.[91] While seeds found in the gut of the dinosaur Isaberrysaura from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina are assigned to Zamiineae, which includes all other living cycads.[92] The Nilssoniales, such as the leaf genus Nilssonia with leaves morphologically similar to those of cycads, have often been considered cycads or cycad relatives, but have been found to be distinct, perhaps more closely allied with Bennettitales.[90]

Gnetophytes

Protognetum from the Middle Jurassic of China is oldest known member of the gnetophytes and the only one known from the Jurassic. It exhibits characteristics of both Gnetum and Ephedra, and is placed in the monotypic family Protognetaceae.[93]

Seed ferns

Seed ferns (Pteridospermatophyta) is a collective term to refer to disparate lineages of fern like plants that produce seeds, with uncertain affinities to living seed plant groups. Prominent groups of Jurassic seed ferns include Caytoniales, which includes the leaf taxon Sagenopteris, Caytonanthus pollen structures and Caytonia ovulate structures, often found in close association. They have frequently been suggested to have been closely related or perhaps ancestral to flowering plants, but no definitive evidence of this has been discovered.[94] The other prominent group is the Corystospermales, including genera like the leaf genus Pachypteris, prominent in the Jurassic of the Northern Hemisphere. As well as pollen organs belonging to Pteruchus and Umkomasia ovulate structures.[95][96]

Czekanowskiales

Czekanowskiales, also known as Leptostrobales, are a group of gymnosperms of uncertain affinities with persistent leaves borne on deciduous short shoots, subtended by scale-like leaves, known from the Late Triassic (possibly Late Permian[97]) to Cretaceous.[98] They are thought to have had a tree or shrub like habit, and formed a conspicuous component of Mesozoic temperate and warm–temperate floras.[97] Jurassic genera include the leaf genera Czekanowskia, Phoenicopsis and Solenites, associated with the ovulate cone Leptostrobus.[98]

Pentoxylales

The Pentoxylales are a small group of gymnosperms of obscure affinities, known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous of Gondwana. These include the stems Pentoxylon, strap-shaped leaves Taeniopteris (more broadly used as a morphogenus representing other plant types) and Nipaniophyllum for well preserved leaves, Sahnia pollen organs, and Carnoconites seed bearing structures. The habit of the group is uncertain, but may have been small trees.[98]

Lower plants

Quillworts

Quillworts virtually identical to modern species are known from the Jurassic onwards. Isoetites rolandii from the Middle Jurassic of Oregon is the earliest known species to represent all major morphological features of modern Isoetes.[99]

Moss

The moss Kulindobryum from the Middle Jurassic of Russia is thought to have affinites with the Splachnaceae, while Bryokhutuliinia from the same region is thought to have affinities with Dicranales.[100] Heinrichsiella from the Jurassic of Patagonia is thought to belong to the families Polytrichaceae or Timmiellaceae basal to Bryidae, and is the oldest representative of the grade.[101]

Liverworts

The liverwort Pellites hamiensis from the Middle Jurassic Xishanyao Formation of China is the oldest record of the family Pelliaceae.[102] Pallaviciniites sandaolingensis from the same deposit is thought to belong to the subclass Pallaviciniineae within the Pallaviciniales.[103] Ricciopsis sandaolingensis also from the same deposit is the only Jurassic record of Ricciaceae.[104]

Regional abundance

In an analysis of the ferns of the Hettangian aged Mecsek Coal Formation found that the predominant groups of ferns by order of abundance belonged to the families Dipteridaceae (48% of collected specimens) Matoniaceae (25%), Osmundaceae (21%), Marattiaceae (6%) and 3 specimens of Coniopteris. They found that most of the ferns likely grew in monospecific thickets in disturbed areas.[72] The Middle-Late Jurassic Daohugou flora of China was dominated by Gymnosperms and ferns, with the most abundant group of gymnosperms being Bennettitales, followed by conifers and ginkgophytes.[105] High latitude floras of the New Zealand Jurassic were of low diversity, with only 43 species being recorded dominated by "conifers, ferns, bennettitaleans, pentoxylaleans and locally, equisetaleans" with Ginkgoales being entirely absent.[106] The flora of the Middle Jurassic Stonesfield Slate of England was dominated by "araucariacean and cheirolepidiacean conifers, bennettitaleans, and leaves of the possible gymnosperm Pelourdea" representing a coastal environment.[107]

Fauna

Aquatic and marine

During the Jurassic period, the primary vertebrates living in the sea were fish and marine reptiles. The latter include ichthyosaurs, which were at the peak of their diversity, plesiosaurs, including pliosaurs, and marine thalattosuchian crocodyliformes of the families Teleosauridae, Machimosauridae and Metriorhynchidae.[108]

Calcareous sabellids (Glomerula) appeared in the Early Jurassic.[109][110] The Jurassic also had diverse encrusting and boring (sclerobiont) communities, and it saw a significant rise in the bioerosion of carbonate shells and hardgrounds. Especially common is the ichnogenus (trace fossil) Gastrochaenolites.[111] During the Jurassic period, about four or five of the twelve clades of planktonic organisms that exist in the fossil record either experienced a massive evolutionary radiation or appeared for the first time.[15]

-

Ichthyosaurus from lower (early) Jurassic slates in southern Germany featured a dolphin-like body shape.

-

Plesiosaurs like Muraenosaurus roamed Jurassic oceans.

Terrestrial

On land, various archosaurian reptiles remained dominant. The Jurassic was a golden age for the large herbivorous dinosaurs known as the sauropods—Camarasaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and many others—that roamed the land late in the period; their foraging grounds were either the prairies of ferns, palm-like cycads and bennettitales, or the higher coniferous growth, according to their adaptations. The smaller Ornithischian herbivore dinosaurs, like stegosaurs and small ornithopods were less predominant, but played important roles. They were preyed upon by large theropods, such as Ceratosaurus, Megalosaurus, Torvosaurus and Allosaurus, all these belong to the 'lizard hipped' or saurischian branch of the dinosaurs.[112]

During the Late Jurassic, the first avialans, like Archaeopteryx, evolved from small coelurosaurian dinosaurs. In the air, pterosaurs were common; they ruled the skies, filling many ecological roles now taken by birds,[113] and may have already produced some of the largest flying animals of all time.[114][115] Within the undergrowth were various types of early mammals, as well as tritylodonts, lizard-like sphenodonts, and early lissamphibians. The rest of the Lissamphibia evolved in this period, introducing the first salamanders and caecilians.[116]

-

Diplodocus, reaching lengths over 30 m, was a common sauropod during the late Jurassic.

-

Allosaurus was one of the largest land predators during the Jurassic.

-

Stegosaurus is one of the most recognizable genera of dinosaurs and lived during the mid to late Jurassic.

-

Aurornis xui, which lived in the late Jurassic, may be the most primitive avialan dinosaur known to date, and is one of the earliest avialans found to date.

Reptiles

Turtles

Stem-group turtles (Testudinata) would diversify during the Jurassic. Jurassic stem-turtles belong to two progessively more advanced clades, the Mesochelydia and Perichelydia.[117] It is thought that the ancestral condition for Mesochelydians is aquatic, as opposed to terrestial for Testudinata.[118] The two modern groups of turtles (Testudines), Pleurodires and Cryptodires, would diverge by the Middle Jurassic.[119][120] Early cryptodire lineages like Xinjiangchelyidae are known from the Middle Jurassic,[121] while an early stem pleurodire lineage, the Platychelyidae is known from the Late Jurassic.[122]

Lepidosaurs

Lepidosaurs, which include squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians (which today only includes the Tuatara) would diversify during the Jurassic. Rynchocephalians would occupy a wide range of morphologies and lifestyles during the Jurassic, such as the specialised aquatic Pleurosauridae and well as the herbivorous Opisthodontia.[123] Crown group squamates first appeared during the Jurassic, with the estimated origin of living lizards during the Early Jurassic (~190 Mya) and the divergence of most major squamatan groups during the Early-Middle Jurassic.[124] Many Jurassic squamates have unclear relationships to living groups.[125] Early members of the snake lineage Ophidia appear during the Middle Jurassic.[126]

Choristoderes

The earliest remains of Choristodera, a group of freshwater aquatic reptiles with uncertain affinities to other reptile groups, would appear in the Middle Jurassic. Only two genera of choristodere are known from the Jurassic, Cteniogenys, thought to be the most basal of choristoderes, which is known from the Middle-Late Jurassic of Europe and Late Jurassic of North America, with similar remains also known from the upper Middle Jurassic of Kyrgyzstan,[127] the other is Coeruleodraco from the Late Jurassic of China, which has close affinities to a clade of non-Neochoristodera from the Early Cretaceous of Asia as well as Lazarussuchus from the Cenozoic of Europe.[128]

Ichthyosaurs

All non-neoichthyosaurian ichthyosaurs would become extinct at the end of the Triassic. Ichthyosaurs would reach their apex of diversity during the Early Jurassic, including the huge apex predator Temnodontosaurus and swordfish-like Eurhinosaurus. Jurassic ichthyosaurs were less morphologically diverse than their Triassic counterparts, and would become less diverse and morphologically conservative though the Jurassic.[129] The Ophthalmosauridae, which would represent the majority of Late Jurassic and Cretaceous ichthyosaurs, would first appear in the early Middle Jurassic (Bajocian).[130]

Plesiosaurs

Plesiosaurs originated at the end of the Triassic (Rhaetian). At the Triassic boundary, all other sauropterygians, including placodonts and nothosaurs became extinct. At least six lineages of plesiosaur crossed the T-J boundary.[131] Plesiosaurs were already diverse in the earliest Jurassic, with the majority of plesiosaurs in the Hettangian aged Blue Lias belonging to the Rhomaleosauridae. Early plesiosaurs were generally small-bodied forms, with body size increasing into the Toarcian.[132] The Middle Jurassic saw the evolution of short necked and large headed pliosaurids from ancestrally small-headed long necked forms.[133]

Amphibians

The vast majority of temnospondyls went extinct at the end of the Triassic, with only brachyopoids surviving into the Jurassic and beyond. Members of the family Brachyopidae are known from Jurassic deposits in Asia,[134] while the chigutisaurid Siderops is known from the Early Jurassic of Australia.[135] Modern lissamphibians would also begin to diversify during the Jurassic. The Early Jurassic Prosalirus thought to represent the first frog relative with a morphology capable of hopping like living frogs.[136] Morphogically recognisable stem-frogs like Notobatrachus are known from the Middle Jurassic.[137] While the earliest salamander-line amphibians are known from the Triassic.[138] Crown group salamanders first appear during the Middle-Late Jurassic of Eurasia, alongside stem-group relatives. Many Jurassic stem-group salamanders, like Marmorerpeton and Kokartus are thought to have been neotenic.[139] Early representatives of crown group salamanders include Chunerpeton, Pangerpeton and Linglongtriton from the Middle-Late Jurassic Yanliao Biota of China, which belong to the Cryptobranchoidea, which contains living asiatic and giant salamanders.[140] While Beiyanerpeton, also from the same biota is thought to be an early member of Salamandroidea, the group which contains all other living salamanders.[141] Salamanders would disperse into North America by the end of the Jurassic, as evidenced by Iridotriton found in the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation.[142] The oldest undisputed stem-caecilian is the Early Jurassic Eocaecilia from Arizona.[143] The fourth group of lissamphibians, the extinct albanerpetontids, would first appear in the Middle Jurassic, represented by Anoualerpeton priscus from the Bathonian of Britain, as well as indeterminate remains from the equivalently aged Anoual Formation of Morocco.[144]

Mammals

Mammals, having originated from cynodonts at the end of the Triassic, diversified extensively during the Jurassic. Important groups of Jurassic mammals include Morganucodonta, Docodonta, Eutriconodonta, Dryolestida, Haramiyida and Multituberculata. While most Jurassic mammals are solely known from isolated teeth and jaw fragments, exceptionally preserved remains have revealed a variety of lifestyles.[145] The docodontan Castorocauda was adapted for aquatic life, similar to the platypus and otters.[146] Some members of Haramiyida[147] and the eutriconodontan tribe Volaticotherini[148] possessed a patagium akin to those of flying squirrels, allowing them to glide through the air. The aardvark like mammal Fruitafossor of uncertain affinities was likely a specialist on colonial insects, similar to living anteaters.[149] Early relatives of monotremes, the Australosphenida, first appear in the Middle Jurassic of Gondwana.[150] Theriiform mammals, represented today by living placentals and marsupials, would also appear during the early Late Jurassic, represented by Juramaia, a eutherian mammal closer to the ancestry of placentals than marsupials.[151] Juramaia is much more advanced than expected for its age, as other theriiform mammals do not appear until the Early Cretaceous.[152] Non-mammalian cynodonts of the families Tritheledontidae and Tritylodontidae survived the T-J extinction, and continued to exist into the Early Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, respectively.[153]

Insects and arachnids

Numerous important insect fossil localities are known from the Jurassic of Eurasia, the most important being the Karabastau Formation of Kazakhstan, and the various Yanliao Biota deposits in Inner Mongolia, China, such as the Daohugou Bed, dating to the Callovian-Oxfordian. The diversity of insects was stagnant throughout the Early and Middle Jurassic, but during the latter third of the Jurassic origination rates increased substantially while extinction rates remained flat.[154] The Middle-Late Jurassic was a time of major diverisification for beetles.[155] Weevils first appear in the fossil record during the Middle-Upper Jurassic, but are suspected to have originated during the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic.[156] The oldest known lepidopterans (the group containing butterflies and moths) are known from the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, with wing scales belonging to the suborder Glossata and Micropterigidae-grade moths from the deposits of this age in Germany.[157] Although modern representatives are not known until the Cenozoic, ectoparasitic insects thought to represent a stem-group to fleas first appear during the Jurassic, such as Pseudopulex jurassicus. These insects are substantially different from modern fleas, lacking the specialised morphology of modern fleas and being larger in size.[158][159] The earliest group of Phasmatodea (stick insects), the winged Susumanioidea, an outgroup to living Phasmatodeans, first appear during the Middle Jurassic.[160] The oldest member of the Mantophasmatidae (gladiators) also appeared during this time.[161]

Only a handful of records of mites are known from the Jurassic, including Jureremus, an Oribatid mite belonging to the family Cymbaeremaeidae known from the Upper Jurassic of Britain and Russia.[162] Spiders would diversify through the Jurassic.[163] The Early Jurassic Seppo koponeni thought to possibly represent a stem-group to Palpimanoidea.[164] Eoplectreurys from the Middle Jurassic of China is considered a stem lineage of Synspermiata. The oldest member of the family Archaeidae, Patarchaea, is known from the Middle Jurassic.[163] Mongolarachne from the Middle Jurassic of China is among the largest known fossil spiders, with legs over 5 centimetres in length.[165] The only scorpion known from the Jurassic is Liassoscorpionides from the Lower Jurassic of Germany, of uncertain placement.[166] Eupnoi Opiliones are known from the Middle Jurassic, including members of the family Sclerosomatidae.[167][168]

Fish

Actinopterygii

Bony fish (Actinopterygii) were major components of Jurassic freshwater and marine ecosystems. Amiiform fish (which today only includes the living bowfin) would first appear during the Early Jurassic, represented by Caturus from the Pliensbachian of Britain, after their first appearance in western Tethys, they would expand to Africa, North America and Southeast and East Asia by the end of the Jurassic. Pycnodontiformes, which first appeared in the western Tethys during the Late Triassic, would expand to South America and Southeast Asia by the end of the Jurassic, having a high diversity in Europe during the Late Jurassic.[169] Teleosts, which make up over 99% of living Actinopterygii, had first appeared during the Triassic in the western Tethys, underwent a major diversification beginning in the Late Jurassic, with early representatives of modern teleost clades such as Elopomorpha and Osteoglossoidei appearing during this time.[170][171] The Pachycormiformes, a group of fish closely allied to teleosts, would first appear in the Early Jurassic, and included both tuna-like predatory and filter feeding forms, the latter including the largest bony fish known to have existed, Leedsichthys, with an estimated maximum length of over 15 metres, known from the late Middle to Late Jurassic.[172]

Chondrichthyes

The Jurassic was a major time in the evolution of Chondrichthyes. Hybodontid sharks such as Hybodus were common in the Early Jurassic in both marine and freshwater settings, however by the Late Jurassic, hybodonts had become minor components of most marine communities, having been largely replaced by modern neoselachians, but would remain common in freshwater and restricted marine environments.[173] The Neoselachii, which contains all living sharks and rays, would radiate in the Jurassic.[174] The oldest known Hexanchiformes are from the Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian) of Europe.[175] The oldest known member of Batoidea (commonly called rays) is Antiquaobatis from the Pliensbachian of Germany.[176] Jurassic batoids known from complete remains retain a conservative, guitarfish-like morphology.[177] The oldest known relatives of the Bullhead shark (Heterodontus) in the order Heterodontiformes first appear in the Early Jurassic, with representatives of the living genus appearing during the Late Jurassic.[178] Carpet sharks (Orectolobiformes) first appear during the Toarcian, represented by Folipistrix and Annea from Europe.[179] The oldest known mackerel sharks (Lamniformes) are known from the Middle Jurassic, represented by the genus Palaeocarcharias., which has a orectolobiform-like bodyform, but shares key similarities in tooth histology with lamniformes, including the absence of orthodentine.[180] The oldest record of Angelsharks (Squatiniformes) is Pseudorhina from the Oxfordian-Tithonian of Europe.[181]

Marine invertebrates

End-Triassic extinction

During the end-Triassic extinction, 46%-72% of all marine genera would become extinct. The effects of the end Triassic extinction were greatest at tropical latitudes, and were more severe in Panthalassa than the Tethys or Boreal oceans. Tropical reef ecosystems would completely collapse during the event, and would not fully recover until much later in the Jurassic. Sessile filter feeders and photosymbiotic organisms were among most severely affected.[182]

Marine ecosystems

Having declined at the T-J boundary. Reefs would substantially expand during the Late Jurassic, including both sponge reefs and scleractinian coral reefs. Late Jurassic reefs were similar in form to modern reefs, but had more microbial carbonates and hypercalcified sponges, and had weak biogenic binding. Reefs would sharply decline at the close of the Jurassic.[183] which caused an associated drop in diversity in decapod crustaceans.[184] Microconchid tube worms, the last remaining order of Tentaculita, a group of animals of uncertain affinites that were convergent on Spirorbis tube worms, had become rare after the Triassic, and had become reduced to the single genus Punctaconchus, which became extinct in the late Bathonian.[185] The earliest planktonic foraminifera are known from the late Early Jurassic (mid Toarcian) of the western Tethys, expanding across the whole Tethys by the Middle Jurassic, before being globallly distributed in tropical latitudes by the Late Jurassic.[186] Coccolithophores and dinoflagellates, which had first appeared during the Triassic, would radiate during the Early-Middle Jurassic, becoming prominent members of the phytoplankton.[187] The oldest known diatom is known from amber found in the Late Jurassic of Thailand, assigned to the living genus Hemiaulus.[188]

Crustaceans

The Jurassic was a significant time for the evolution of decapods.[184] The first true crabs (Brachyura) would appear during the Early Jurassic, with the earliest being Eocarcinus praecursor from the early Pliensbachian of England, which lacked the carcinisation of modern crabs.[189] and Eoprosopon klugi from the late Pliensbachian of Germany, which possibly belongs to the living family Homolodromiidae.[190] Most Jurassic crabs are only known from dorsal carapace pieces, which makes it difficult to determine their relationships.[191] While rare in the Early and Middle Jurassic, crabs would become abundant during the Late Jurassic as they expanded from their ancestral silty sea floor habitat into hard substrate habitats like reefs, with crevices in reefs helping to hide from predators[191][184] Hermit crabs would also first appear during the Jurassic, with the earliest known being Schobertella hoelderi from the late Hettangian of Germany.[192] Early hermit crabs are associated with ammonite shells rather than those of gastropods.[193] Glypheids, which today are only known from two species, reached their peak diversity during the Jurassic, with around 150 species out of a total fossil record of 250 being known from the period.[194]

Brachiopods

Brachiopod diversity declined during the T-J extinction. Spire bearing groups (Spiriferinida and Athyridida) would significantly decline at the T-J boundary and would not recover their biodiversity, becoming extinct in the TOAE.[46] Rhynchonellida and Terebratulida would also decline during the T-J extincton but would rebound during the Early Jurassic, neither clade would develop any significant morphological variation.[195] Brachiopods would substantially decline in the Late Jurassic, the causes of which are poorly understood. Proposed reasons include increased predation, competition with bivalves, enhanced bioturbation or increased grazing pressure.[196]

Molluscs

Ammonites

Ammonites were devastated by the end-Triassic extinction, with only the family Psiloceratidae of the suborder Phylloceratina surviving, and becoming ancestral to all later Jurassic and Cretaceous ammonites. Ammonites would explosively diversify during the Early Jurassic, with the orders Psiloceratina, Ammonitina, Lytoceratina, Haploceratina, Perisphinctina and Ancyloceratina all appearing during the Jurassic. Ammonite faunas during the Jurassic were regional, being divided into around 20 distinguishable provinces and subprovinces in two realms, the northern high latitude Pan-Boreal realm, consisting of the Arctic, northern Panthalassa and northern Atlantic regions, and the equatorial-southern Pan-Tethyan realm, which included the Tethys and most of Panthalassa.[197]

Bivalves

The end Triassic extinction had a severe impact on bivalve diveristy, though it had little impact on bivalve ecological diversity. The extinction was selective, having less of an impact on deep burrowers, but there is no evidence of a differential impact between surface living (epifaunal) and burrowing (infaunal) bivalves.[198] Rudists, the dominant reef building organisms of the Cretaceous, would first appear in the Late Jurassic (mid Oxfordian) in the northern margin of the western Tethys region, expanding to the eastern Tethys by the end of the Jurassic.[199]

Belemnites

The oldest definitive records of the squid-like belemnites are from the earliest Jurassic (Hettangian-Sinemurian) of Europe and Japan, and would expand worldwide during the Jurassic.[200] Belemnites were shallow water dwellers, inhabiting the upper 200 metres of the water column on the continental shelves and in the littoral zone. They were key components of Jurassic ecosystems, both as predators and prey, as evidenced by the abundance of belemnite guards in Jurassic rocks.[201]

References

Notes

- ^ A 140 Ma age for the Jurassic-Cretaceous instead of the usually accepted 145 Ma was proposed in 2014 based on a stratigraphic study of Vaca Muerta Formation in Neuquén Basin, Argentina.[3] Víctor Ramos, one of the authors of the study proposing the 140 Ma boundary age, sees the study as a "first step" toward formally changing the age in the International Union of Geological Sciences.[4]

- ^ "Ich hatte mich auf einer geognostischen Reise, die ich 1795 durch das südliche Franken, die westliche Schweiz und Ober-Italien machte, davon überzeugt, daß der Jura-Kalkstein, welchen Werner zu seinem Muschelkalk rechnete, eine eigne Formation bildete. In meiner Schrift über die unterirdischen Gasarten, welche mein Bruder Wilhelm von Humboldt 1799 während meines Aufenthalts in Südamerika herausgab, wird der Formation, die ich vorläufig mit dem Namen Jura-Kalkstein bezeichnete, zuerst gedacht." ('On a geological tour that I made in 1795 through southern France, western Switzerland and upper Italy, I convinced myself that the Jura limestone, which Werner included in his shell limestone, constituted a separate formation. In my paper about subterranean types of gases, which my brother Wilhelm von Humboldt published in 1799 during my stay in South America, the formation, which I provisionally designated with the name "Jura limestone", is first conceived.')[9]

- ^ "[…] die ausgebreitete Formation, welche zwischen dem alten Gips und neueren Sandstein liegt, und welchen ich vorläufig mit dem Nahmen Jura-Kalkstein bezeichne." '… the widespread formation which lies between the old gypsum and the more recent sandstone and which I provisionally designate with the name "Jura limestone".'[10]

Citations

- ^ "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy.

- ^ "Jurassic". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Vennari et al. 2014, pp. 374–385.

- ^ Jaramillo 2014.

- ^ Hallam 1986, pp. 765–768.

- ^ a b Hölder 1964.

- ^ a b Arkell 1956.

- ^ Rollier 1903.

- ^ von Humboldt 1858, p. 632.

- ^ von Humboldt 1799, p. 39.

- ^ Pieńkowski et al. 2008, pp. 823–922.

- ^ Brongniart 1829.

- ^ von Buch, L., 1839. Über den Jura in Deutschland. Der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ogg, J.G.; Hinnov, L.A.; Huang, C. (2012), "Jurassic", The Geologic Time Scale, Elsevier, pp. 731–791, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-59425-9.00026-3, ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9, retrieved 2020-12-05

- ^ a b Kazlev 2002.

- ^ Hillebrandt, A.v.; Krystyn, L.; Kürschner, W.M.; Bonis, N.R.; Ruhl, M.; Richoz, S.; Schobben, M. A. N.; Urlichs, M.; Bown, P.R.; Kment, K.; McRoberts, C.A. (2013-09-01). "The Global Stratotype Sections and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Jurassic System at Kuhjoch (Karwendel Mountains, Northern Calcareous Alps, Tyrol, Austria)". Episodes. 36 (3): 162–198. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2013/v36i3/001. ISSN 0705-3797.

- ^ Bloos, Gert; Page, Kevin N. (2002-03-01). "Global Stratotype Section and Point for base of the Sinemurian Stage (Lower Jurassic)". Episodes. 25 (1): 22–28. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2002/v25i1/003. ISSN 0705-3797.

- ^ Meister, Christian; Aberhan, Martin; Blau, Joachim; Dommergues, Jean-Louis; Feist-Burkhardt, Susanne; Hailwood, Ernie A.; Hart, Malcom; Hesselbo, Stephen P.; Hounslow, Mark W.; Hylton, Mark; Morton, Nicol (2006-06-01). "The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Pliensbachian Stage (Lower Jurassic), Wine Haven, Yorkshire, UK". Episodes. 29 (2): 93–106. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2006/v29i2/003. ISSN 0705-3797.

- ^ Fantasia, Alicia; Adatte, Thierry; Spangenberg, Jorge E.; Font, Eric; Duarte, Luís V.; Föllmi, Karl B. (November 2019). "Global versus local processes during the Pliensbachian–Toarcian transition at the Peniche GSSP, Portugal: A multi-proxy record". Earth-Science Reviews. 198: 102932. Bibcode:2019ESRv..19802932F. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102932.

- ^ Barrón, Eduardo; Ureta, Soledad; Goy, Antonio; Lassaletta, Luis (August 2010). "Palynology of the Toarcian–Aalenian Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) at Fuentelsaz (Lower–Middle Jurassic, Iberian Range, Spain)". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 162 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2010.04.003.

- ^ Pavia, G.; Enay, R. (1997-03-01). "Definition of the Aalenian-Bajocian Stage boundary". Episodes. 20 (1): 16–22. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1997/v20i1/004. ISSN 0705-3797.

- ^ López, Fernández; Rafael, Sixto; Pavia, Giulio; Erba, Elisabetta; Guiomar, Myette; Paiva Henriques, María Helena; Lanza, Roberto; Mangold, Charles; Morton, Nicol; Olivero, Davide; Tiraboschi, Daniele (2009). "The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for base of the Bathonian Stage (Middle Jurassic), Ravin du Bès Section, SE France" (PDF). Episodes. 32 (4): 222–248. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2009/v32i4/001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ BARSKI, Marcin (2018-09-06). "Dinoflagellate cyst assemblages across the Oxfordian/Kimmeridgian boundary (Upper Jurassic) at Flodigarry, Staffin Bay, Isle of Skye, Scotland – a proposed GSSP for the base of the Kimmeridgian". Volumina Jurassica. XV (1): 51–62. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.4594. ISSN 1731-3708.

- ^ WIMBLEDON, William A.P. (2017-12-27). "Developments with fixing a Tithonian/Berriasian (J/K) boundary". Volumina Jurassica (1): 0. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0010.7467. ISSN 1731-3708.

- ^ Gautier D.L. (2005). "Kimmeridgian Shales Total Petroleum System of the North Sea Graben Province" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Wilson, A. O. (2020). "Chapter 1 Introduction to the Jurassic Arabian Intrashelf Basin". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 53 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1144/M53.1. ISSN 0435-4052. S2CID 226967035.

- ^ Abdula, Rzger A. (August 2015). "Hydrocarbon potential of Sargelu Formation and oil-source correlation, Iraqi Kurdistan". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 8 (8): 5845–5868. doi:10.1007/s12517-014-1651-0. ISSN 1866-7511. S2CID 129120960.

- ^ Soran University; Abdula, Rzger A. (2016-10-16). "Source Rock Assessment of Naokelekan Formation in Iraqi Kurdistan". Journal of Zankoy Sulaimani - Part A. 19 (1): 103–124. doi:10.17656/jzs.10589.

- ^ Ao, Weihua; Huang, Wenhui; Weng, Chengmin; Xiao, Xiuling; Liu, Dameng; Tang, Xiuyi; Chen, Ping; Zhao, Zhigen; Wan, Huan; Finkelman, Robert B. (January 2012). "Coal petrology and genesis of Jurassic coal in the Ordos Basin, China". Geoscience Frontiers. 3 (1): 85–95. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2011.09.004.

- ^ Tennant, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D.; Upchurch, Paul (2016-09-02). "Sea level regulated tetrapod diversity dynamics through the Jurassic/Cretaceous interval". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12737. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712737T. doi:10.1038/ncomms12737. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5025807. PMID 27587285.

- ^ Holm‐Alwmark, S.; Alwmark, C.; Ferrière, L.; Lindström, S.; Meier, M. M. M.; Scherstén, A.; Herrmann, M.; Masaitis, V. L.; Mashchak, M. S.; Naumov, M. V.; Jourdan, F. (August 2019). "An Early Jurassic age for the Puchezh‐Katunki impact structure (Russia) based on 40 Ar/ 39 Ar data and palynology". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 54 (8): 1764–1780. Bibcode:2019M&PS...54.1764H. doi:10.1111/maps.13309. ISSN 1086-9379.

- ^ Scotese 2003.

- ^ Barth, G.; Franz, M.; Heunisch, C.; Ernst, W.; Zimmermann, J.; Wolfgramm, M. (2018-01-01). "Marine and terrestrial sedimentation across the T–J transition in the North German Basin". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 489: 74–94. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.09.029. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Korte, Christoph; Hesselbo, Stephen P.; Ullmann, Clemens V.; Dietl, Gerd; Ruhl, Micha; Schweigert, Günter; Thibault, Nicolas (December 2015). "Jurassic climate mode governed by ocean gateway". Nature Communications. 6 (1): 10015. doi:10.1038/ncomms10015. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4682040. PMID 26658694.

- ^ Geiger, Markus; Clark, David Norman; Mette, Wolfgang (March 2004). "Reappraisal of the timing of the breakup of Gondwana based on sedimentological and seismic evidence from the Morondava Basin, Madagascar". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 38 (4): 363–381. Bibcode:2004JAfES..38..363G. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2004.02.003.

- ^ Nguyen, Luan C.; Hall, Stuart A.; Bird, Dale E.; Ball, Philip J. (June 2016). "Reconstruction of the East Africa and Antarctica continental margins: AFRICA-ANTARCTICA RECONSTRUCTION". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 121 (6): 4156–4179. doi:10.1002/2015JB012776.

- ^ Boschman, Lydian M.; van Hinsbergen, Douwe J. J. (July 2016). "On the enigmatic birth of the Pacific Plate within the Panthalassa Ocean". Science Advances. 2 (7): e1600022. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600022. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5919776. PMID 29713683.

- ^ Danise, Silvia; Holland, Steven M. (July 2018). "A Sequence Stratigraphic Framework for the Middle to Late Jurassic of the Sundance Seaway, Wyoming: Implications for Correlation, Basin Evolution, and Climate Change". The Journal of Geology. 126 (4): 371–405. doi:10.1086/697692. ISSN 0022-1376.

- ^ Haq, Bilal U. (2018-01-01). "Jurassic Sea-Level Variations: A Reappraisal". GSA Today: 4–10. doi:10.1130/GSATG359A.1.

- ^ Stanley & Hardie 1998.

- ^ Monroe & Wicander 1997, p. 607.

- ^ a b c d e Jacobs 1997, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Them, T.R.; Gill, B.C.; Caruthers, A.H.; Gröcke, D.R.; Tulsky, E.T.; Martindale, R.C.; Poulton, T.P.; Smith, P.L. (February 2017). "High-resolution carbon isotope records of the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic) from North America and implications for the global drivers of the Toarcian carbon cycle". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 459: 118–126. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.11.021.

- ^ Dera, Guillaume; Neige, Pascal; Dommergues, Jean-Louis; Fara, Emmanuel; Laffont, Rémi; Pellenard, Pierre (January 2010). "High-resolution dynamics of Early Jurassic marine extinctions: the case of Pliensbachian–Toarcian ammonites (Cephalopoda)". Journal of the Geological Society. 167 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1144/0016-76492009-068. ISSN 0016-7649.

- ^ Caruthers, Andrew H.; Smith, Paul L.; Gröcke, Darren R. (September 2013). "The Pliensbachian–Toarcian (Early Jurassic) extinction, a global multi-phased event". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 386: 104–118. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.05.010.

- ^ a b Vörös, Attila; Kocsis, Ádám T.; Pálfy, József (September 2016). "Demise of the last two spire-bearing brachiopod orders (Spiriferinida and Athyridida) at the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) extinction event". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 457: 233–241. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.06.022.

- ^ Maxwell, Erin E.; Vincent, Peggy (2015-11-06). "Effects of the early Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event on ichthyosaur body size and faunal composition in the Southwest German Basin". Paleobiology. 42 (1): 117–126. doi:10.1017/pab.2015.34. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ Xu, Weimu; Ruhl, Micha; Jenkyns, Hugh C.; Hesselbo, Stephen P.; Riding, James B.; Selby, David; Naafs, B. David A.; Weijers, Johan W. H.; Pancost, Richard D.; Tegelaar, Erik W.; Idiz, Erdem F. (February 2017). "Carbon sequestration in an expanded lake system during the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event". Nature Geoscience. 10 (2): 129–134. doi:10.1038/ngeo2871. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ Müller, Tamás; Jurikova, Hana; Gutjahr, Marcus; Tomašových, Adam; Schlögl, Jan; Liebetrau, Volker; Duarte, Luís v.; Milovský, Rastislav; Suan, Guillaume; Mattioli, Emanuela; Pittet, Bernard (2020-12-01). "Ocean acidification during the early Toarcian extinction event: Evidence from boron isotopes in brachiopods". Geology. 48 (12): 1184–1188. doi:10.1130/G47781.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Trecalli, Alberto; Spangenberg, Jorge; Adatte, Thierry; Föllmi, Karl B.; Parente, Mariano (December 2012). "Carbonate platform evidence of ocean acidification at the onset of the early Toarcian oceanic anoxic event". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 357–358: 214–225. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.09.043.

- ^ Ettinger, Nicholas P.; Larson, Toti E.; Kerans, Charles; Thibodeau, Alyson M.; Hattori, Kelly E.; Kacur, Sean M.; Martindale, Rowan C. (2020-09-23). Eberli, Gregor (ed.). "Ocean acidification and photic‐zone anoxia at the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event: Insights from the Adriatic Carbonate Platform". Sedimentology: sed.12786. doi:10.1111/sed.12786. ISSN 0037-0746.

- ^ Elgorriaga, Andrés; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Cúneo, N. Rubén (July 2019). "Relictual Lepidopteris (Peltaspermales) from the Early Jurassic Cañadón Asfalto Formation, Patagonia, Argentina". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 180 (6): 578–596. doi:10.1086/703461. ISSN 1058-5893.

- ^ Mander, Luke; Kürschner, Wolfram M.; McElwain, Jennifer C. (2010-08-31). "An explanation for conflicting records of Triassic–Jurassic plant diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (35): 15351–15356. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004207107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 20713737.

- ^ Barbacka, Maria; Pacyna, Grzegorz; Kocsis, Ádam T.; Jarzynka, Agata; Ziaja, Jadwiga; Bodor, Emese (August 2017). "Changes in terrestrial floras at the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary in Europe". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 480: 80–93. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.05.024.

- ^ Bomfleur, Benjamin; Blomenkemper, Patrick; Kerp, Hans; McLoughlin, Stephen (2018), "Polar Regions of the Mesozoic–Paleogene Greenhouse World as Refugia for Relict Plant Groups", Transformative Paleobotany, Elsevier, pp. 593–611, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-813012-4.00024-3, ISBN 978-0-12-813012-4, retrieved 2020-11-12

- ^ Bateman, Richard M (2020-01-01). Ort, Donald (ed.). "Hunting the Snark: the flawed search for mythical Jurassic angiosperms". Journal of Experimental Botany. 71 (1): 22–35. doi:10.1093/jxb/erz411. ISSN 0022-0957.

- ^ Stockey, Ruth A.; Rothwell, Gar W. (July 2020). "Diversification of crown group Araucaria : the role of Araucaria famii sp. nov. in the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) radiation of Araucariaceae in the Northern Hemisphere". American Journal of Botany. 107 (7): 1072–1093. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1505. ISSN 0002-9122.

- ^ Escapa, Ignacio H.; Catalano, Santiago A. (October 2013). "Phylogenetic Analysis of Araucariaceae: Integrating Molecules, Morphology, and Fossils". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 174 (8): 1153–1170. doi:10.1086/672369. ISSN 1058-5893.

- ^ Stockey, Ruth A.; Rothwell, Gar W. (March 2013). "Pararaucaria carrii sp. nov., Anatomically Preserved Evidence for the Conifer Family Cheirolepidiaceae in the Northern Hemisphere". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 174 (3): 445–457. doi:10.1086/668614. ISSN 1058-5893.

- ^ Escapa, Ignacio; Cúneo, Rubén; Axsmith, Brian (September 2008). "A new genus of the Cupressaceae (sensu lato) from the Jurassic of Patagonia: Implications for conifer megasporangiate cone homologies". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 151 (3–4): 110–122. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2008.03.002.

- ^ Contreras, Dori L.; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Iribarren, Rocio C.; Cúneo, N. Rubén (October 2019). "Reconstructing the Early Evolution of the Cupressaceae: A Whole-Plant Description of a New Austrohamia Species from the Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic), Argentina". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 180 (8): 834–868. doi:10.1086/704831. ISSN 1058-5893.

- ^ Spencer, A. R. T.; Mapes, G.; Bateman, R. M.; Hilton, J.; Rothwell, G. W. (2015-06-01). "Middle Jurassic evidence for the origin of Cupressaceae: A paleobotanical context for the roles of regulatory genetics and development in the evolution of conifer seed cones". American Journal of Botany. 102 (6): 942–961. doi:10.3732/ajb.1500121. ISSN 0002-9122.

- ^ Rothwell, Gar W.; Mapes, Gene; Stockey, Ruth A.; Hilton, Jason (April 2012). "The seed cone Eathiestrobus gen. nov.: Fossil evidence for a Jurassic origin of Pinaceae". American Journal of Botany. 99 (4): 708–720. doi:10.3732/ajb.1100595.

- ^ Pole, Mike; Wang, Yongdong; Bugdaeva, Eugenia V.; Dong, Chong; Tian, Ning; Li, Liqin; Zhou, Ning (2016-12-15). "The rise and demise of Podozamites in east Asia—An extinct conifer life style". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Mesozoic ecosystems - Climate and Biota. 464: 97–109. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.02.037. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Dong, Chong; Shi, Gongle; Herrera, Fabiany; Wang, Yongdong; Herendeen, Patrick S; Crane, Peter R (2020-06-18). "Middle–Late Jurassic fossils from northeastern China reveal morphological stasis in the catkin-yew". National Science Review: nwaa138. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwaa138. ISSN 2095-5138.

- ^ Nosova, N. V.; Kiritchkova, A. I. (October 2008). "A new species and a new combination of the Mesozoic genus Podocarpophyllum Gomolitzky (Coniferales)". Paleontological Journal. 42 (6): 665–674. doi:10.1134/S0031030108060129. ISSN 0031-0301.

- ^ Harris, T.M., 1979. The Yorkshire Jurassic flora, V. Coniferales. Trustees of the British 417 Museum (Natural History), London, 166 pp.

- ^ Reymanówna, Maria (January 1987). "A Jurassic podocarp from Poland". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 51 (1–3): 133–143. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(87)90026-1.

- ^ Zhou, Zhi-Yan (March 2009). "An overview of fossil Ginkgoales". Palaeoworld. 18 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2009.01.001.

In the extant species G. biloba, leaves from the same tree on different shoots or from shoots at different developmental stages may be referrable to the different leaf types (morphogenera) established for fossil ginkgoaleans.

- ^ Nosova, Natalya (October 2013). "Revision of the genus Grenana Samylina from the Middle Jurassic of Angren, Uzbekistan". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 197: 226–252. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2013.06.005.

- ^ Herrera, Fabiany; Shi, Gongle; Ichinnorov, Niiden; Takahashi, Masamichi; Bugdaeva, Eugenia V.; Herendeen, Patrick S.; Crane, Peter R. (2017-03-21). "The presumed ginkgophyte Umaltolepis has seed-bearing structures resembling those of Peltaspermales and Umkomasiales". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (12): E2385–E2391. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621409114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5373332. PMID 28265050.

- ^ a b Barbacka, Maria; Kustatscher, Evelyn; Bodor, Emese R. (2019-03-01). "Ferns of the Lower Jurassic from the Mecsek Mountains (Hungary): taxonomy and palaeoecology". PalZ. 93 (1): 151–185. doi:10.1007/s12542-018-0430-8. ISSN 1867-6812.

- ^ Regalado, Ledis; Schmidt, Alexander R.; Müller, Patrick; Niedermeier, Lisa; Krings, Michael; Schneider, Harald (July 2019). "Heinrichsia cheilanthoides gen. et sp. nov., a fossil fern in the family Pteridaceae (Polypodiales) from the Cretaceous amber forests of Myanmar". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 57 (4): 329–338. doi:10.1111/jse.12514. ISSN 1674-4918.

- ^ Li, Chunxiang; Miao, Xinyuan; Zhang, Li-Bing; Ma, Junye; Hao, Jiasheng (January 2020). "Re-evaluation of the systematic position of the Jurassic–Early Cretaceous fern genus Coniopteris". Cretaceous Research. 105: 104136. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.04.007.

- ^ Bomfleur, Benjamin; Grimm, Guido W.; McLoughlin, Stephen (2015-06-30). "Osmunda pulchella sp. nov. from the Jurassic of Sweden—reconciling molecular and fossil evidence in the phylogeny of modern royal ferns (Osmundaceae)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15 (1): 126. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0400-7. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 4487210. PMID 26123220.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ McLoughlin, Stephen; Bomfleur, Benjamin (December 2016). "Biotic interactions in an exceptionally well preserved osmundaceous fern rhizome from the Early Jurassic of Sweden". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 464: 86–96. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.01.044.

- ^ Elgorriaga, Andrés; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Bomfleur, Benjamin; Cúneo, Rubén; Ottone, Eduardo G. (February 2015). "Reconstruction and Phylogenetic Significance of a New Equisetum Linnaeus Species from the Lower Jurassic of Cerro Bayo (Chubut Province, Argentina)". Ameghiniana. 52 (1): 135–152. doi:10.5710/AMGH.15.09.2014.2758. ISSN 0002-7014.

- ^ Gould, R. E. 1968. Morphology of Equisetum laterale Phillips, 1829, and E. bryanii sp. nov. from the Mesozoic of south‐eastern Queensland. Australian Journal of Botany 16: 153–176.

- ^ a b Elgorriaga, Andrés; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Rothwell, Gar W.; Tomescu, Alexandru M. F.; Rubén Cúneo, N. (August 2018). "Origin of Equisetum : Evolution of horsetails (Equisetales) within the major euphyllophyte clade Sphenopsida". American Journal of Botany. 105 (8): 1286–1303. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1125.

- ^ Channing, Alan; Zamuner, Alba; Edwards, Dianne; Guido, Diego (2011). "Equisetum thermale sp. nov. (Equisetales) from the Jurassic San Agustín hot spring deposit, Patagonia: Anatomy, paleoecology, and inferred paleoecophysiology". American Journal of Botany. 98 (4): 680–697. doi:10.3732/ajb.1000211. ISSN 1537-2197.

- ^ Lantz, Trevor C; Rothwell, Gar W; Stockey, Ruth A (September 1999). "Conantiopteris schuchmanii, gen. et sp. nov., and the Role of Fossils in Resolving the Phylogeny of Cyatheaceae s.l." Journal of Plant Research. 112 (3): 361–381. doi:10.1007/PL00013890. ISSN 0918-9440.