Greenhouse gas emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities strengthen the greenhouse effect, contributing to climate change. Most is carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. The largest emitters include coal in China and large oil and gas companies, many state-owned by OPEC and Russia. Human-caused emissions have increased atmospheric carbon dioxide by about 50% over pre-industrial levels. The growing levels of emissions have varied, but it was consistent among all greenhouse gases (GHG). Emissions in the 2010s averaged 56 billion tons a year, higher than ever before.[4]

Electricity generation and transport are major emitters, the largest single source being coal-fired power stations with 20% of GHG. Deforestation and other changes in land use also emit carbon dioxide and methane. The largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions is agriculture, closely followed by gas venting and fugitive emissions from the fossil-fuel industry. The largest agricultural methane source is livestock. Agricultural soils emit nitrous oxide partly due to fertilizers. Similarly, fluorinated gases from refrigerants play an outsized role in total human emissions.

At current emission rates averaging six and a half tonnes per person per year, before 2030 temperatures may have increased by 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) over pre-industrial levels, which is the limit for the G7 countries and aspirational limit of the Paris Agreement.[5]

Measurements and calculations

Global greenhouse gas emissions are about 50 Gt per year[6] (6.6t per person[7]) and for 2019 have been estimated at 57 Gt CO2 eq including 5 Gt due to land use change.[8] In 2019, approximately 34% [20 GtCO2-eq] of total net anthropogenic GHG emissions came from the energy supply sector, 24% [14 GtCO2-eq] from industry, 22% [13 GtCO2-eq]from agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU), 15% [8.7 GtCO2-eq] from transport and 6% [3.3 GtCO2-eq] from buildings.[9]

Carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N

2O), methane, three groups of fluorinated gases (sulfur hexafluoride (SF

6), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and perfluorocarbons (PFCs)) are the major anthropogenic greenhouse gases, and are regulated under the Paris Agreement.[10]: 147 [11]

Although CFCs are greenhouse gases, they are regulated by the Montreal Protocol, which was motivated by CFCs' contribution to ozone depletion rather than by their contribution to global warming. Note that ozone depletion has only a minor role in greenhouse warming, though the two processes are sometimes confused in the media. In 2016, negotiators from over 170 nations meeting at the summit of the United Nations Environment Programme reached a legally binding accord to phase out hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) in the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.[12][13][14]

There are several ways of measuring greenhouse gas emissions. Some variables that have been reported include:[15]

- Definition of measurement boundaries: Emissions can be attributed geographically, to the area where they were emitted (the territory principle) or by the activity principle to the territory that produced the emissions. These two principles result in different totals when measuring, for example, electricity importation from one country to another, or emissions at an international airport.

- Time horizon of different gases: The contribution of given greenhouse gas is reported as a CO2 equivalent. The calculation to determine this takes into account how long that gas remains in the atmosphere. This is not always known accurately[clarification needed] and calculations must be regularly updated to reflect new information.

- The measurement protocol itself: This may be via direct measurement or estimation. The four main methods are the emission factor-based method, mass balance method, predictive emissions monitoring systems, and continuous emissions monitoring systems. These methods differ in accuracy, cost, and usability. Public information from space-based measurements of carbon dioxide by Climate Trace is expected to reveal individual large plants before the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference.[16]

These measures are sometimes used by countries to assert various policy/ethical positions on climate change.[17]: 94 The use of different measures leads to a lack of comparability, which is problematic when monitoring progress towards targets. There are arguments for the adoption of a common measurement tool, or at least the development of communication between different tools.[15]

Emissions may be tracked over long time periods, known as historical or cumulative emissions measurements. Cumulative emissions provide some indicators of what is responsible for greenhouse gas atmospheric concentration build-up.[18]: 199

The national accounts balance tracks emissions based on the difference between a country's exports and imports. For many richer nations, the balance is negative because more goods are imported than they are exported. This result is mostly due to the fact that it is cheaper to produce goods outside of developed countries, leading developed countries to become increasingly dependent on services and not goods. A positive account balance would mean that more production was occurring within a country, so more operational factories would increase carbon emission levels.[19]

Emissions may also be measured across shorter time periods. Emissions changes may, for example, be measured against the base year of 1990. 1990 was used in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as the base year for emissions, and is also used in the Kyoto Protocol (some gases are also measured from the year 1995).[10]: 146, 149 A country's emissions may also be reported as a proportion of global emissions for a particular year.

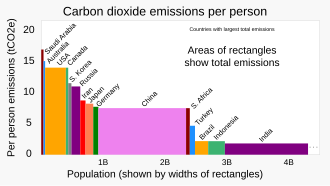

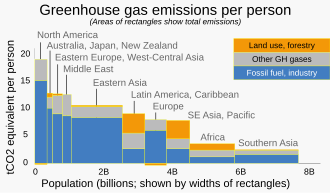

Another measurement is of per capita emissions. This divides a country's total annual emissions by its mid-year population.[20]: 370 Per capita emissions may be based on historical or annual emissions.[17]: 106–107

While cities are sometimes considered to be disproportionate contributors to emissions, per-capita emissions tend to be lower for cities than the averages in their countries.[21]

At current emission rates, before 2030 temperatures may have increased by 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) over pre-industrial levels,[22][23] which is the limit for the G7 countries[24] and aspirational limit of the Paris Agreement.[25]

Overview of main sources

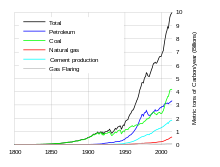

Since about 1750, human activity has increased the concentration of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. As of 2021, measured atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide were almost 50% higher than pre-industrial levels.[26] Natural sources of carbon dioxide are more than 20 times greater than sources due to human activity,[27] but over periods longer than a few years natural sources are closely balanced by natural sinks, mainly photosynthesis of carbon compounds by plants and marine plankton. Absorption of terrestrial infrared radiation by longwave absorbing gases makes Earth a less efficient emitter. Therefore, in order for Earth to emit as much energy as is absorbed, global temperatures must increase.

Burning fossil fuels is estimated to have emitted 62% of 2015 human GhG.[28] The largest single source is coal-fired power stations, with 20% of GHG as of 2021.[29]

The main sources of greenhouse gases due to human activity are:

- burning of fossil fuels and deforestation leading to higher carbon dioxide concentrations in the air.

- land use change (mainly deforestation in the tropics) accounts for about a quarter of total anthropogenic GHG emissions.[30]

- livestock enteric fermentation and manure management,[31] paddy rice farming, land use and wetland changes, man-made lakes,[32] pipeline losses, and covered vented landfill emissions leading to higher methane atmospheric concentrations. Many of the newer style fully vented septic systems that enhance and target the fermentation process also are sources of atmospheric methane.

- use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in refrigeration systems, and use of CFCs and halons in fire suppression systems and manufacturing processes.

- agricultural activities, including the use of fertilizers, that lead to higher nitrous oxide (N

2O) concentrations.

The seven sources of CO2 from fossil fuel combustion are (with percentage contributions for 2000–2004):[33]

This list needs updating, as it uses an out-of-date source. See the 2019 IPCC report for newer data.[needs update]

- Liquid fuels (e.g., gasoline, fuel oil): 36%

- Solid fuels (e.g., coal): 35%

- Gaseous fuels (e.g., natural gas): 20%

- Cement production: 3%

- Flaring gas industrially and at wells: 1%

- Non-fuel hydrocarbons: 1%

- "International bunker fuels" of transport not included in national inventories: 4%

The largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions is agriculture, closely followed by gas venting and fugitive emissions from the fossil-fuel industry.[34][35] The largest agricultural methane source is livestock. Cattle (raised for both beef and milk, as well as for inedible outputs like manure and draft power) are the animal species responsible for the most emissions, representing about 65% of the livestock sector’s emissions.[36] Agricultural soils emit nitrous oxide partly due to fertilizers.[37]

The major sources of Greenhouse gases (GHG) are:

- Land Use (CO2 emissions)

- Forestry (CO2-LULUCF)

- Nitrous Acid (N2O)

- Fluorinated gases (F-gases)

- Compromising hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

- Perfluorocarbons (PFCs)

- sulphur hexafluoride (SF6)

- nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)

A 2017 survey of corporations responsible for global emissions found that 100 companies were responsible for 71% of global direct and indirect emissions, and that state-owned companies were responsible for 59% of their emissions.[38][39]

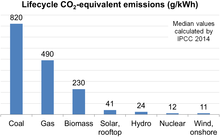

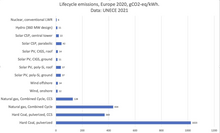

Emissions by energy source

| Technology | Min. | Median | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently commercially available technologies | |||

| Coal – PC | 740 | 820 | 910 |

| Gas – combined cycle | 410 | 490 | 650 |

| Biomass – Dedicated | 130 | 230 | 420 |

| Solar PV – Utility scale | 18 | 48 | 180 |

| Solar PV – rooftop | 26 | 41 | 60 |

| Geothermal | 6.0 | 38 | 79 |

| Concentrated solar power | 8.8 | 27 | 63 |

| Hydropower | 1.0 | 24 | 22001 |

| Wind Offshore | 8.0 | 12 | 35 |

| Nuclear | 3.7 | 12 | 110 |

| Wind Onshore | 7.0 | 11 | 56 |

| Pre‐commercial technologies | |||

| Ocean (Tidal and wave) | 5.6 | 17 | 28 |

1 see also environmental impact of reservoirs#Greenhouse gases.

| Technology | gCO2eq/kWh | |

|---|---|---|

| Hard coal | PC, without CCS | 1000 |

| IGCC, without CCS | 850 | |

| SC, without CCS | 950 | |

| PC, with CCS | 370 | |

| IGCC, with CCS | 280 | |

| SC, with CCS | 330 | |

| Natural gas | NGCC, without CCS | 430 |

| NGCC, with CCS | 130 | |

| Hydro | 660 MW [43] | 150 |

| 360 MW | 11 | |

| Nuclear | average | 5.1 |

| CSP | tower | 22 |

| trough | 42 | |

| PV | poly-Si, ground-mounted | 37 |

| poly-Si, roof-mounted | 37 | |

| CdTe, ground-mounted | 12 | |

| CdTe, roof-mounted | 15 | |

| CIGS, ground-mounted | 11 | |

| CIGS, roof-mounted | 14 | |

| Wind | onshore | 12 |

| offshore, concrete foundation | 14 | |

| offshore, steel foundation | 13 | |

List of acronyms:

- PC — pulverized coal

- CCS — carbon capture and storage

- IGCC — integrated gasification combined cycle

- SC — supercritical

- NGCC — natural gas combined cycle

- CSP — concentrated solar power

- PV — photovoltaic power

Relative CO2 emission from various fuels

One liter of gasoline, when used as a fuel, produces 2.32 kg (about 1300 liters or 1.3 cubic meters) of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. One US gallon produces 19.4 lb (1,291.5 gallons or 172.65 cubic feet).[44][45][46]

The mass of carbon dioxide that is released when one MJ of energy is released from fuel can be estimated to a good approximation.[47] For the chemical formula of diesel we use as an approximation C

nH

2n. Note that diesel is a mixture of different molecules. As carbon has a molar mass of 12 g/mol and hydrogen (atomic!) has a molar mass of about 1 g/mol, so the fraction by weight of carbon in diesel is roughly 12/14. The reaction of diesel combustion is given by:

2C

nH

2n + 3nO

2 ⇌ 2nCO

2 + 2nH

2O

Carbon dioxide has a molar mass of 44g/mol as it consists of 2 atoms of oxygen (16 g/mol) and 1 atom of carbon (12 g/mol). So 12 g of carbon yield 44 g of Carbon dioxide. Diesel has an energy content of 42.6 MJ per kg or 23.47 gram of Diesel contain 1 MJ of energy. Putting everything together the mass of carbon dioxide that is produced by releasing 1MJ of energy from diesel fuel can be calculated as:

For gasoline, with 22 g/MJ and a ratio of carbon to hydrogen atoms of about 6 to 14, the estimated value of carbon emission for 1MJ of energy is:

| Fuel name | CO2 emitted (lbs/106 Btu) |

CO2 emitted (g/MJ) |

CO2 emitted (g/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen gas | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Natural gas | 117 | 50.30 | 181.08 |

| Liquefied petroleum gas | 139 | 59.76 | 215.14 |

| Propane | 139 | 59.76 | 215.14 |

| Aviation gasoline | 153 | 65.78 | 236.81 |

| Automobile gasoline | 156 | 67.07 | 241.45 |

| Kerosene | 159 | 68.36 | 246.10 |

| Fuel oil | 161 | 69.22 | 249.19 |

| Tires/tire derived fuel | 189 | 81.26 | 292.54 |

| Wood and wood waste | 195 | 83.83 | 301.79 |

| Coal (bituminous) | 205 | 88.13 | 317.27 |

| Coal (sub-bituminous) | 213 | 91.57 | 329.65 |

| Coal (lignite) | 215 | 92.43 | 332.75 |

| Petroleum coke | 225 | 96.73 | 348.23 |

| Tar-sand bitumen | [citation needed] | [citation needed] | [citation needed] |

| Coal (anthracite) | 227 | 97.59 | 351.32 |

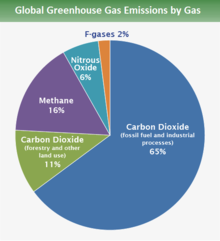

Emissions by greenhouse gas

GHG emissions 2019 by gas type

without land-use change

using 100 year GWP

Total: 51.8 GtCO2e[49]

2O nitrous oxide (6%)

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the dominant emitted greenhouse gas, while methane (CH4) emissions almost have the same short-term impact.[51] Nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases (F-Gases) play a minor role.

GHG emissions are measured in CO2 equivalents determined by their global warming potential (GWP), which depends on their lifetime in the atmosphere. Estimations largely depend on the ability of oceans and land sinks to absorb these gases. Short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) including methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), tropospheric ozone and black carbon persist in the atmosphere for a period ranging from days to 15 years; whereas carbon dioxide can remain in the atmosphere for millennia.[52] Reducing SLCP emissions can cut the ongoing rate of global warming by almost half and reduce the projected Arctic warming by two-thirds.[53]

GHG emissions in 2019 were estimated at 57.4 GtCO2e, while CO2 emissions alone made up 42.5 Gt including land-use change (LUC).[54]

While mitigation measures for decarbonization are essential on the longer-term, they could result in weak near-term warming because sources of carbon emissions often also co-emit air pollution. Hence, pairing measures that target carbon dioxide with measures targeting non-CO2 pollutants – short-lived climate pollutants, which have faster effects on the climate, is essential for climate goals.[55]

Carbon dioxide (CO2)

- Fossil fuel: oil, gas and coal (89%) are the major driver of anthropogenic global warming with annual emissions of 35.6 GtCO2 in 2019.[56]

- Cement production (4%) is estimated at 1.42 GtCO2

- Land-use change (LUC) is the imbalance of deforestation and reforestation. Estimations are very uncertain at 4.5 GtCO2. Wildfires alone cause annual emissions of about 7 GtCO2[57][58]

- Non-energy use of fuels, carbon losses in coke ovens, and flaring in crude oil production.[56]

Methane (CH4)

Methane has a high immediate impact with a 5-year global warming potential of up to 100.[51] Given this, the current 389 Mt of methane emissions[59] has about the same short-term global warming effect as CO2 emissions, with a risk to trigger irreversible changes in climate and ecosystems. For methane, a reduction of about 30% below current emission levels would lead to a stabilization in its atmospheric concentration.

- Fossil fuels (32%), again, account for most of the methane emissions including coal mining (12% of methane total), gas distribution and leakages (11%) as well as gas venting in oil production (9%).[59][60]

- Livestock (28%) with cattle (21%) as the dominant source, followed by buffalo (3%), sheep (2%), and goats (1.5%).[59][61]

- Human waste and wastewater (21%): When biomass waste in landfills and organic substances in domestic and industrial wastewater is decomposed by bacteria in anaerobic conditions, substantial amounts of methane are generated.[60]

- Rice cultivation (10%) on flooded rice fields is another agricultural source, where anaerobic decomposition of organic material produces methane.[60]

Nitrous oxide (N

2O)

N2O has a high GWP and significant Ozone Depleting Potential. It is estimated that the global warming potential of N2O over 100 years is 265 times greater than CO2.[62] For N2O, a reduction of more than 50% would be required for a stabilization.

- Most emissions (56%) by agriculture, especially meat production: cattle (droppings on pasture), fertilizers, animal manure.[60]

- Combustion of fossil fuels (18%) and bio fuels.[63]

- Industrial production of adipic acid and nitric acid.

F-Gases

Fluorinated gases include hydrofluorocarbons (HFC), perfluorocarbons (PFC), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). They are used by switchgear in the power sector, semiconductor manufacture, aluminium production and a large unknown source of SF6.[64] Continued phase down of manufacture and use of HFCs under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol will help reduce HFC emissions and concurrently improve the energy efficiency of appliances that use HFCs like air conditioners, freezers and other refrigeration devices.

Black carbon

Black carbon is formed through the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, biofuel, and biomass. It is not a greenhouse gas but a climate forcing agent. Black carbon can absorb sunlight and reduce albedo when deposited on snow and ice. Indirect heating can be caused by the interaction with clouds.[65] Black carbon stays in the atmosphere for only several days to weeks.[66] Emissions may be mitigated by upgrading coke ovens, installing particulate filters on diesel-based engines, reducing routine flaring, and minimizing open burning of biomass.

Emissions by sector

Global greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to different sectors of the economy. This provides a picture of the varying contributions of different types of economic activity to global warming, and helps in understanding the changes required to mitigate climate change.

Manmade greenhouse gas emissions can be divided into those that arise from the combustion of fuels to produce energy, and those generated by other processes. Around two thirds of greenhouse gas emissions arise from the combustion of fuels.[68]

Energy may be produced at the point of consumption, or by a generator for consumption by others. Thus emissions arising from energy production may be categorized according to where they are emitted, or where the resulting energy is consumed. If emissions are attributed at the point of production, then electricity generators contribute about 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[69] If these emissions are attributed to the final consumer then 24% of total emissions arise from manufacturing and construction, 17% from transportation, 11% from domestic consumers, and 7% from commercial consumers.[70] Around 4% of emissions arise from the energy consumed by the energy and fuel industry itself.

The remaining third of emissions arise from processes other than energy production. 12% of total emissions arise from agriculture, 7% from land use change and forestry, 6% from industrial processes, and 3% from waste.[68] Around 6% of emissions are fugitive emissions, which are waste gases released by the extraction of fossil fuels.

As of 2020[update] Secunda CTL is the world's largest single emitter, at 56.5 million tonnes CO2 a year.[71]

Agriculture

The amount of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture is significant: The agriculture, forestry and land use sector contribute between 13% and 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[72] Emissions come from direct greenhouse gas emissions (for example from rice production and livestock farming).[73] and from indirect emissions. With regards to direct emissions, nitrous oxide and methane make up over half of total greenhouse gas emission from agriculture.[74] Indirect emissions on the other hand come from the conversion of non-agricultural land such as forests into agricultural land.[75][76] Furthermore, there is also fossil fuel consumption for transport and fertilizer production. For example, the manufacture and use of nitrogen fertilizer contributes around 5% of all global greenhouse gas emissions.[77] Livestock farming is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions.[78] At the same time, livestock farming is affected by climate change.

Farm animals' digestive systems can be put into two categories: monogastric and ruminant. Ruminant cattle for beef and dairy rank high in greenhouse gas emissions. In comparison, monogastric, or pigs and poultry-related foods, are lower. The consumption of the monogastric types may yield less emissions. Monogastric animals have a higher feed-conversion efficiency, and also do not produce as much methane.[79] Non-ruminant livestock, such as poultry, emit far fewer greenhouse gases.[80]

There are many strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture (this is one of the goals of climate-smart agriculture). Mitigation measures in the food system can be divided into four categories. These are demand-side changes, ecosystem protections, mitigation on farms, and mitigation in supply chains. On the demand side, limiting food waste is an effective way to reduce food emissions. Changes to a diet less reliant on animal products such as plant-based diets are also effective.[81]: XXV This could include milk substitutes and meat alternatives. Several methods are also under investigation to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from livestock farming. These include genetic selection,[82][83] introduction of methanotrophic bacteria into the rumen,[84][85] vaccines, feeds,[86] diet modification and grazing management.[87][88][89]Aviation

Approximately 3.5% of the overall human impacts on climate are from the aviation sector. The impact of the sector on climate in the late 20 years had doubled, but the part of the contribution of the sector in comparison to other sectors did not change because other sectors grew as well.[90]

Buildings and construction

In 2018, manufacturing construction materials and maintaining buildings accounted for 39% of carbon dioxide emissions from energy and process-related emissions. Manufacture of glass, cement, and steel accounted for 11% of energy and process-related emissions.[91] Because building construction is a significant investment, more than two-thirds of buildings in existence will still exist in 2050. Retrofitting existing buildings to become more efficient will be necessary to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement; it will be insufficient to only apply low-emission standards to new construction.[92] Buildings that produce as much energy as they consume are called zero-energy buildings, while buildings that produce more than they consume are energy-plus. Low-energy buildings are designed to be highly efficient with low total energy consumption and carbon emissions—a popular type is the passive house.[91]

The global design and construction industry is responsible for approximately 39 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.[93] Green building practices that avoid emissions or capture the carbon already present in the environment, allow for reduced footprint of the construction industry, for example, use of hempcrete, cellulose fiber insulation, and landscaping.[94]

In 2019, the building sector was responsible for 12 GtCO2-eq emissions. More than 95% of these emissions were carbon, and the remaining 5% were CH4 N2O and halocarbon.[95]

Digital sector

The digital sector produces between 2% and 4% of global GHG emissions,[96] a large part of which is from chipmaking.[97] However the sector reduces emissions from other sectors which have a larger global share, such as transport of people,[98] and possibly buildings and industry.[99]

Health care

The healthcare sector produces 4.4% - 4.6% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[100]

Steel and aluminum

Steel and aluminum are key economic sectors for the carbon capture and storage. According to a 2013 study, "in 2004, the steel industry along emits about 590M tons of CO2, which accounts for 5.2% of the global anthropogenic GHG emissions. CO2 emitted from steel production primarily comes from energy consumption of fossil fuel as well as the use of limestone to purify iron oxides."[101]

Electricity generation

Coal-fired power stations are the single largest emitter, with over 20% of global GhG in 2018.[102] Although much less polluting than coal plants, natural gas-fired power plants are also major emitters,[103] taking electricity generation as a whole over 25% in 2018.[104] Notably, just 5% of the world's power plants account for almost three-quarters of carbon emissions from electricity generation, based on an inventory of more than 29,000 fossil-fuel power plants across 221 countries.[105] In the 2022 IPCC report, it is noted that providing modern energy services universally would only increase greenhouse gas emissions by a few percent at most. This slight increase means that the additional energy demand that comes from supporting decent living standards for all would be far lower than current average energy consumption.[106]

Plastics

Plastics are produced mainly from fossil fuels. It was estimated that between 3% and 4% of global GHG emissions are associated with plastics' life cycles.[107] The EPA estimates[108] as many as five mass units of carbon dioxide are emitted for each mass unit of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) produced—the type of plastic most commonly used for beverage bottles,[109] the transportation produce greenhouse gases also.[110] Plastic waste emits carbon dioxide when it degrades. In 2018 research claimed that some of the most common plastics in the environment release the greenhouse gases methane and ethylene when exposed to sunlight in an amount that can affect the earth climate.[111][112]

Due to the lightness of plastic versus glass or metal, plastic may reduce energy consumption. For example, packaging beverages in PET plastic rather than glass or metal is estimated to save 52% in transportation energy, if the glass or metal package is single-use, of course.

In 2019 a new report "Plastic and Climate" was published. According to the report, the production and incineration of plastics will contribute in the equivalent of 850 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere in 2019. With the current trend, annual life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of plastics will grow to 1.34 billion tonnes by 2030. By 2050, the life cycle emissions of plastics could reach 56 billion tonnes, as much as 14 percent of the Earth's remaining carbon budget.[113] The report says that only solutions which involve a reduction in consumption can solve the problem, while others like biodegradable plastic, ocean cleanup, using renewable energy in plastic industry can do little, and in some cases may even worsen it.[114]

Sanitation sector

Wastewater as well as sanitation systems are known to contribute to greenhouse-gas emissions (GHG)[quantify] mainly through the breakdown of excreta during the treatment process. This results in the generation of methane gas, that is then released into the environment. Emissions from the sanitation and wastewater sector have been focused mainly on treatment systems, particularly treatment plants, and this accounts for the bulk of the carbon footprint for the sector.[115]

In as much as climate impacts from wastewater and sanitation systems present global risks, low-income countries experience greater risks in many cases. In recent years,[when?] attention to adaptation needs within the sanitation sector is just beginning to gain momentum.[116]

Tourism

According to UNEP, global tourism is a significant contributor to the increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.[117]

Trucking and haulage

Over a quarter of global transport CO2 emissions are from road freight,[118] so many countries are further restricting truck CO2 emissions to help limit climate change.[119]

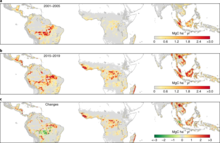

Deforestation

Deforestation is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. A study shows annual carbon emissions (or carbon loss) from tropical deforestation have doubled during the last two decades and continue to increase. (0.97 ±0.16 PgC per year in 2001–2005 to 1.99 ±0.13 PgC per year in 2015–2019)[121][120]

Emissions by other characteristics

The responsibility for anthropogenic climate change differs substantially among individuals, e.g. between groups or cohorts.

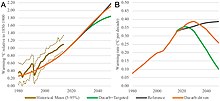

Generational

Researchers report that, on average, the elderly played "a leading role in driving up GHG emissions in the past decade and are on the way to becoming the largest contributor" due to factors such as demographic transition, low informed concern about climate change and high expenditures on carbon-intensive products like energy which is used i.a. for heating rooms and private transport.[122][123] They are less affected by climate change impacts,[124] but have e.g. the same vote-weights for the available electoral options.

By socio-economic class

Fueled by the consumptive lifestyle of wealthy people, the wealthiest 5% of the global population has been responsible for 37% of the absolute increase in greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. Almost half of the increase in absolute global emissions has been caused by the richest 10% of the population.[126] In the newest report from the IPCC 2022, it states that the lifestyle consumptions of the poor and middle class in emerging economies produce approximately 5–50 times less the amount that the high class in already developed high-income countries.[127][128] Variations in regional, and national per capita emissions partly reflect different development stages, but they also vary widely at similar income levels. The 10% of households with the highest per capita emissions contribute a disproportionately large share of global household GHG emissions.[128]

Studies find that the most affluent citizens of the world are responsible for most environmental impacts, and robust action by them is necessary for prospects of moving towards safer environmental conditions.[129][130]

According to a 2020 report by Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute,[131][132] the richest 1% of the global population have caused twice as much carbon emissions as the poorest 50% over the 25 years from 1990 to 2015.[133][134][135] This was, respectively, during that period, 15% of cumulative emissions compared to 7%.[136] The bottom half of the population is directly-responsible for less than 20% of energy footprints and consume less than the top 5% in terms of trade-corrected energy. The largest disproportionality was identified to be in the domain of transport, where e.g. the top 10% consume 56% of vehicle fuel and conduct 70% of vehicle purchases.[137] However, wealthy individuals are also often shareholders and typically have more influence[138] and, especially in the case of billionaires, may also direct lobbying efforts, direct financial decisions, and/or control companies:

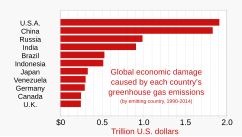

Regional and national attribution of emissions

From land-use change

Land-use change, e.g., the clearing of forests for agricultural use, can affect the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere by altering how much carbon flows out of the atmosphere into carbon sinks.[140] Accounting for land-use change can be understood as an attempt to measure "net" emissions, i.e., gross emissions from all sources minus the removal of emissions from the atmosphere by carbon sinks.[17]: 92–93

There are substantial uncertainties in the measurement of net carbon emissions.[141] Additionally, there is controversy over how carbon sinks should be allocated between different regions and over time.[17]: 93 For instance, concentrating on more recent changes in carbon sinks is likely to favour those regions that have deforested earlier, e.g., Europe.

Greenhouse gas intensity

Greenhouse gas intensity is a ratio between greenhouse gas emissions and another metric, e.g., gross domestic product (GDP) or energy use. The terms "carbon intensity" and "emissions intensity" are also sometimes used.[142] Emission intensities may be calculated using market exchange rates (MER) or purchasing power parity (PPP).[17]: 96 Calculations based on MER show large differences in intensities between developed and developing countries, whereas calculations based on PPP show smaller differences. According to a study discussing the relationship between urbanization and carbon emissions, urbanization is becoming a huge player in the global carbon cycle. Depending on total carbon emissions done by a city that hasn't invested in carbon efficiency or improved resource management, the global carbon cycle is projected to reach 75% of the world population by 2030.[143]

Cumulative and historical emissions

Cumulative anthropogenic (i.e., human-emitted) emissions of CO2 from fossil fuel use are a major cause of global warming,[144] and give some indication of which countries have contributed most to human-induced climate change. In particular, CO2 stays in the atmosphere for at least 150 years, whilst methane and nitrous oxides generally disappear within a decade or so. The graph gives some indication of which regions have contributed most to human-induced climate change.[145] [146]: 15 When these numbers are calculated per capita cumulative emissions based on then-current population the situation is shown even more clearly. The ratio in per capita emissions between industrialized countries and developing countries was estimated at more than 10 to 1.

Non-OECD countries accounted for 42% of cumulative energy-related CO2 emissions between 1890 and 2007.[147]: 179–80 Over this time period, the US accounted for 28% of emissions; the EU, 23%; Japan, 4%; other OECD countries 5%; Russia, 11%; China, 9%; India, 3%; and the rest of the world, 18%.[147]: 179–80

Overall, developed countries accounted for 83.8% of industrial CO2 emissions over this time period, and 67.8% of total CO2 emissions. Developing countries accounted for industrial CO2 emissions of 16.2% over this time period, and 32.2% of total CO2 emissions.

In comparison, humans have emitted more greenhouse gases than the Chicxulub meteorite impact event which caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.[148]

Transport, together with electricity generation, is the major source of greenhouse gas emissions in the EU. Greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector continue to rise, in contrast to power generation and nearly all other sectors. Since 1990, transportation emissions have increased by 30%. The transportation sector accounts for around 70% of these emissions. The majority of these emissions are caused by passenger vehicles and vans. Road travel is the first major source of greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, followed by aircraft and maritime.[149][150] Waterborne transportation is still the least carbon-intensive mode of transportation on average, and it is an essential link in sustainable multimodal freight supply chains.[151]

Buildings, like industry, are directly responsible for around one-fifth of greenhouse gas emissions, primarily from space heating and hot water consumption. When combined with power consumption within buildings, this figure climbs to more than one-third.[152][153][154]

Within the EU, the agricultural sector presently accounts for roughly 10% of total greenhouse gas emissions, with methane from livestock accounting for slightly more than half of 10%.[155]

Estimates of total CO2 emissions do include biotic carbon emissions, mainly from deforestation.[17]: 94 Including biotic emissions brings about the same controversy mentioned earlier regarding carbon sinks and land-use change.[17]: 93–94 The actual calculation of net emissions is very complex, and is affected by how carbon sinks are allocated between regions and the dynamics of the climate system.

The graphic shows the logarithm of 1850–2019 fossil fuel CO2 emissions;[156] natural log on left, actual value of Gigatons per year on right. Although emissions increased during the 170-year period by about 3% per year overall, intervals of distinctly different growth rates (broken at 1913, 1945, and 1973) can be detected. The regression lines suggest that emissions can rapidly shift from one growth regime to another and then persist for long periods of time. The most recent drop in emissions growth - by almost 3 percentage points - was at about the time of the 1970s energy crisis. Percent changes per year were estimated by piecewise linear regression on the log data and are shown on the plot; the data are from The Integrated Carbon Observation system.[157]

Changes since a particular base year

The sharp acceleration in CO2 emissions since 2000 to more than a 3% increase per year (more than 2 ppm per year) from 1.1% per year during the 1990s is attributable to the lapse of formerly declining trends in carbon intensity of both developing and developed nations. China was responsible for most of global growth in emissions during this period. Localised plummeting emissions associated with the collapse of the Soviet Union have been followed by slow emissions growth in this region due to more efficient energy use, made necessary by the increasing proportion of it that is exported.[33] In comparison, methane has not increased appreciably, and N

2O by 0.25% y−1.

Using different base years for measuring emissions has an effect on estimates of national contributions to global warming.[146]: 17–18 [158] This can be calculated by dividing a country's highest contribution to global warming starting from a particular base year, by that country's minimum contribution to global warming starting from a particular base year. Choosing between base years of 1750, 1900, 1950, and 1990 has a significant effect for most countries.[146]: 17–18 Within the G8 group of countries, it is most significant for the UK, France and Germany. These countries have a long history of CO2 emissions (see the section on Cumulative and historical emissions).

Embedded emissions

One way of attributing greenhouse gas emissions is to measure the embedded emissions (also referred to as "embodied emissions") of goods that are being consumed. Emissions are usually measured according to production, rather than consumption.[159] For example, in the main international treaty on climate change (the UNFCCC), countries report on emissions produced within their borders, e.g., the emissions produced from burning fossil fuels.[147]: 179 [160]: 1 Under a production-based accounting of emissions, embedded emissions on imported goods are attributed to the exporting, rather than the importing, country. Under a consumption-based accounting of emissions, embedded emissions on imported goods are attributed to the importing country, rather than the exporting, country.

Davis and Caldeira (2010)[160]: 4 found that a substantial proportion of CO2 emissions are traded internationally. The net effect of trade was to export emissions from China and other emerging markets to consumers in the US, Japan, and Western Europe.

By country

Annual emissions

Annual per capita emissions in the industrialized countries are typically as much as ten times the average in developing countries.[10]: 144 Due to China's fast economic development, its annual per capita emissions are quickly approaching the levels of those in the Annex I group of the Kyoto Protocol (i.e., the developed countries excluding the US).[161] Other countries with fast growing emissions are South Korea, Iran, and Australia (which apart from the oil rich Persian Gulf states, now has the highest per capita emission rate in the world). On the other hand, annual per capita emissions of the EU-15 and the US are gradually decreasing over time.[161] Emissions in Russia and Ukraine have decreased fastest since 1990 due to economic restructuring in these countries.[162]

Energy statistics for fast-growing economies are less accurate than those for industrialized countries.[161]

The greenhouse gas footprint refers to the emissions resulting from the creation of products or services. It is more comprehensive than the commonly used carbon footprint, which measures only carbon dioxide, one of many greenhouse gases.[citation needed]

2015 was the first year to see both total global economic growth and a reduction of carbon emissions.[163]

Top emitter countries

In 2019, China, the United States, India, the EU27+UK, Russia, and Japan - the world's largest CO2 emitters - together accounted for 51% of the population, 62.5% of global gross domestic product, 62% of total global fossil fuel consumption and emitted 67% of total global fossil CO2. Emissions from these five countries and the EU28 show different changes in 2019 compared to 2018: the largest relative increase is found for China (+3.4%), followed by India (+1.6%). On the contrary, the EU27+UK (-3.8%), the United States (-2.6%), Japan (-2.1%) and Russia (-0.8%) reduced their fossil CO2 emissions.[164]

| Country | total emissions (Mton) |

Share (%) |

per capita (ton) |

per GDP (ton/k$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Total | 38,016.57 | 100.00 | 4.93 | 0.29 |

| 11,535.20 | 30.34 | 8.12 | 0.51 | |

| 5,107.26 | 13.43 | 15.52 | 0.25 | |

| EU27+UK | 3,303.97 | 8.69 | 6.47 | 0.14 |

| 2,597.36 | 6.83 | 1.90 | 0.28 | |

| 1,792.02 | 4.71 | 12.45 | 0.45 | |

| 1,153.72 | 3.03 | 9.09 | 0.22 | |

| International Shipping | 730.26 | 1.92 | - | - |

| 702.60 | 1.85 | 8.52 | 0.16 | |

| 701.99 | 1.85 | 8.48 | 0.68 | |

| 651.87 | 1.71 | 12.70 | 0.30 | |

| International Aviation | 627.48 | 1.65 | - | - |

| 625.66 | 1.65 | 2.32 | 0.20 | |

| 614.61 | 1.62 | 18.00 | 0.38 | |

| 584.85 | 1.54 | 15.69 | 0.32 | |

| 494.86 | 1.30 | 8.52 | 0.68 | |

| 485.00 | 1.28 | 3.67 | 0.19 | |

| 478.15 | 1.26 | 2.25 | 0.15 | |

| 433.38 | 1.14 | 17.27 | 0.34 | |

| 415.78 | 1.09 | 5.01 | 0.18 | |

| 364.91 | 0.96 | 5.45 | 0.12 | |

| 331.56 | 0.87 | 5.60 | 0.13 | |

| 317.65 | 0.84 | 8.35 | 0.25 | |

| 314.74 | 0.83 | 4.81 | 0.10 | |

| 305.25 | 0.80 | 3.13 | 0.39 | |

| 277.36 | 0.73 | 14.92 | 0.57 | |

| 276.78 | 0.73 | 11.65 | 0.23 | |

| 275.06 | 0.72 | 3.97 | 0.21 | |

| 259.31 | 0.68 | 5.58 | 0.13 | |

| 255.37 | 0.67 | 2.52 | 0.22 | |

| 248.83 | 0.65 | 7.67 | 0.27 | |

| 223.63 | 0.59 | 1.09 | 0.22 | |

| 222.61 | 0.59 | 22.99 | 0.34 | |

| 199.41 | 0.52 | 4.42 | 0.20 | |

| 197.61 | 0.52 | 4.89 | 0.46 | |

| 196.40 | 0.52 | 4.48 | 0.36 | |

| 180.57 | 0.47 | 4.23 | 0.37 | |

| 156.41 | 0.41 | 9.13 | 0.16 | |

| 150.64 | 0.40 | 1.39 | 0.16 | |

| 110.16 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.14 | |

| 110.06 | 0.29 | 3.36 | 0.39 | |

| 106.53 | 0.28 | 38.82 | 0.41 | |

| 105.69 | 0.28 | 9.94 | 0.25 | |

| 104.41 | 0.27 | 9.03 | 0.18 | |

| 100.22 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.10 | |

| 98.95 | 0.26 | 23.29 | 0.47 | |

| 94.99 | 0.25 | 2.90 | 0.40 | |

| 92.78 | 0.24 | 18.55 | 0.67 | |

| 90.52 | 0.24 | 15.23 | 0.98 | |

| 89.89 | 0.24 | 4.90 | 0.20 | |

| 86.55 | 0.23 | 1.74 | 0.12 | |

| 78.63 | 0.21 | 4.04 | 0.14 | |

| 73.91 | 0.19 | 2.02 | 0.27 | |

| 72.36 | 0.19 | 8.25 | 0.14 | |

| 70.69 | 0.19 | 7.55 | 0.44 | |

| 68.33 | 0.18 | 7.96 | 0.18 | |

| 66.34 | 0.17 | 7.03 | 0.37 | |

| 65.57 | 0.17 | 5.89 | 0.20 | |

| 56.29 | 0.15 | 1.71 | 0.13 | |

| 53.37 | 0.14 | 9.09 | 0.10 | |

| 53.18 | 0.14 | 5.51 | 0.17 | |

| 52.05 | 0.14 | 7.92 | 0.51 | |

| 48.47 | 0.13 | 4.73 | 0.14 | |

| 48.31 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.17 | |

| 47.99 | 0.13 | 8.89 | 0.14 | |

| 44.75 | 0.12 | 4.45 | 0.08 | |

| 44.02 | 0.12 | 5.88 | 0.10 | |

| 43.41 | 0.11 | 7.81 | 0.16 | |

| 43.31 | 0.11 | 6.20 | 0.27 | |

| 42.17 | 0.11 | 1.64 | 0.36 | |

| 40.70 | 0.11 | 2.38 | 0.21 | |

| 39.37 | 0.10 | 4.57 | 0.07 | |

| 38.67 | 0.10 | 8.07 | 0.18 | |

| 36.55 | 0.10 | 7.54 | 0.09 | |

| 35.99 | 0.09 | 6.60 | 0.20 | |

| 35.98 | 0.09 | 3.59 | 0.25 | |

| 35.93 | 0.09 | 11.35 | 0.91 | |

| 35.44 | 0.09 | 21.64 | 0.48 | |

| 33.50 | 0.09 | 9.57 | 0.68 | |

| 32.74 | 0.09 | 23.81 | 0.90 | |

| 32.07 | 0.08 | 2.72 | 0.25 | |

| 31.12 | 0.08 | 5.39 | 0.09 | |

| 31.04 | 0.08 | 2.70 | 0.11 | |

| 29.16 | 0.08 | 1.58 | 1.20 | |

| 28.34 | 0.07 | 2.81 | 0.28 | |

| 27.57 | 0.07 | 1.31 | 0.10 | |

| 27.44 | 0.07 | 4.52 | 0.27 | |

| 27.28 | 0.07 | 2.48 | 0.14 | |

| 25.82 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.12 | |

| 24.51 | 0.06 | 2.15 | 0.24 | |

| 22.57 | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.13 | |

| 21.20 | 0.06 | 1.21 | 0.15 | |

| 19.81 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.09 | |

| 19.12 | 0.05 | 4.62 | 0.16 | |

| 18.50 | 0.05 | 14.19 | 0.38 | |

| 18.25 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.07 | |

| 16.84 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.10 | |

| 16.49 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.23 | |

| 15.66 | 0.04 | 55.25 | 1.67 | |

| 15.37 | 0.04 | 7.38 | 0.19 | |

| 15.02 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.15 | |

| 13.77 | 0.04 | 4.81 | 0.13 | |

| 13.56 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.10 | |

| 13.47 | 0.04 | 3.45 | 0.24 | |

| 13.34 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.09 | |

| 11.92 | 0.03 | 1.92 | 0.35 | |

| 11.63 | 0.03 | 2.75 | 0.09 | |

| 11.00 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.13 | |

| 10.89 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.17 | |

| 10.86 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.26 | |

| 10.36 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 0.19 | |

| 10.10 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.11 | |

| 9.81 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.18 | |

| 9.74 | 0.03 | 16.31 | 0.14 | |

| 9.26 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.24 | |

| 9.23 | 0.02 | 2.29 | 0.27 | |

| 8.98 | 0.02 | 1.80 | 0.09 | |

| 8.92 | 0.02 | 4.28 | 0.26 | |

| 8.92 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.28 | |

| 8.47 | 0.02 | 1.21 | 0.09 | |

| 8.38 | 0.02 | 4.38 | 0.14 | |

| 8.15 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.21 | |

| 7.66 | 0.02 | 1.64 | 0.33 | |

| 7.50 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.12 | |

| 7.44 | 0.02 | 2.56 | 0.26 | |

| 7.41 | 0.02 | 6.19 | 0.21 | |

| 7.15 | 0.02 | 1.11 | 0.13 | |

| 7.04 | 0.02 | 2.96 | 0.17 | |

| 7.02 | 0.02 | 15.98 | 0.26 | |

| 6.78 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.12 | |

| 6.56 | 0.02 | 1.89 | 0.09 | |

| 5.92 | 0.02 | 2.02 | 0.15 | |

| 5.91 | 0.02 | 36.38 | 1.51 | |

| 5.86 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.17 | |

| 5.80 | 0.02 | 1.05 | 0.33 | |

| 5.66 | 0.01 | 1.93 | 0.14 | |

| 5.34 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.06 | |

| 4.40 | 0.01 | 1.67 | 0.18 | |

| 4.33 | 0.01 | 3.41 | 0.15 | |

| 4.20 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.09 | |

| 4.07 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.11 | |

| 3.93 | 0.01 | 11.53 | 0.19 | |

| 3.91 | 0.01 | 1.07 | 0.04 | |

| 3.83 | 0.01 | 13.34 | 0.85 | |

| 3.64 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.08 | |

| 3.58 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.18 | |

| 3.48 | 0.01 | 1.65 | 0.11 | |

| 3.47 | 0.01 | 2.55 | 0.14 | |

| 3.02 | 0.01 | 3.40 | - | |

| 2.98 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 2.92 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.09 | |

| 2.85 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.22 | |

| 2.45 | 0.01 | 6.08 | 0.18 | |

| 2.36 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.08 | |

| 2.12 | 0.01 | 2.57 | 0.24 | |

| 2.06 | 0.01 | 3.59 | 0.22 | |

| 1.95 | 0.01 | 5.07 | - | |

| 1.87 | 0.00 | 4.17 | - | |

| 1.62 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| 1.52 | 0.00 | 1.94 | 0.20 | |

| 1.40 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.10 | |

| 1.36 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 0.11 | |

| 1.33 | 0.00 | 59.88 | 4.09 | |

| 1.27 | 0.00 | 1.98 | 0.02 | |

| 1.21 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.17 | |

| 1.15 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.04 | |

| 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.11 | |

| 1.05 | 0.00 | 1.06 | 0.20 | |

| 1.05 | 0.00 | 10.98 | 0.37 | |

| 1.04 | 0.00 | 2.41 | 0.05 | |

| 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| 1.02 | 0.00 | 1.83 | 0.26 | |

| 0.97 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.57 | |

| 0.91 | 0.00 | 2.02 | 0.09 | |

| 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.04 | |

| 0.78 | 0.00 | 7.39 | 0.19 | |

| 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.08 | |

| 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.13 | |

| 0.69 | 0.00 | 19.88 | 0.45 | |

| 0.61 | 0.00 | 2.06 | - | |

| 0.60 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 0.10 | |

| 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.11 | |

| 0.54 | 0.00 | 9.47 | 0.19 | |

| 0.51 | 0.00 | 4.90 | 0.24 | |

| 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.11 | |

| 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.11 | |

| 0.40 | 0.00 | 6.38 | 0.09 | |

| 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.10 | |

| 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.14 | |

| 0.35 | 0.00 | 5.75 | 0.14 | |

| 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.65 | 0.11 | |

| 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.51 | - | |

| 0.23 | 0.00 | 2.10 | 0.12 | |

| 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.08 | |

| 0.19 | 0.00 | 3.44 | 0.14 | |

| 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.19 | |

| 0.15 | 0.00 | 1.32 | 0.11 | |

| 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.11 | |

| 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.09 | |

| 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.20 | |

| 0.13 | 0.00 | 3.70 | 0.13 | |

| 0.12 | 0.00 | 3.77 | 0.17 | |

| 0.10 | 0.00 | 1.38 | 0.12 | |

| 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.09 | |

| 0.06 | 0.00 | 9.72 | - | |

| 0.04 | 0.00 | 2.51 | - | |

| 0.03 | 0.00 | 10.87 | - | |

| 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.13 | |

| 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.12 | |

| 0.02 | 0.00 | 3.87 | - | |

| Faroes | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

United States

China

China's greenhouse gas emissions are the largest of any country in the world both in production and consumption terms, and stem mainly from coal burning, including coal power, coal mining,[177] and blast furnaces producing iron and steel.[178] When measuring production-based emissions, China emitted over 14 gigatonnes (Gt) CO2eq of greenhouse gases in 2019,[179] 27% of the world total.[180][181] When measuring in consumption-based terms, which adds emissions associated with imported goods and extracts those associated with exported goods, China accounts for 13 gigatonnes (Gt) or 25% of global emissions.[182]

These high levels of emissions are due to China's large population; the country's per person emissions have remained considerably lower than those in the developed world.[182] This corresponds to over 10.1 tonnes CO2eq emitted per person each year, slightly over the world average and the EU average but significantly lower than the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the United States, with its 17.6 tonnes per person.[182] Accounting for historic emissions, OECD countries produced four times more CO2 in cumulative emissions than China, due to developed countries' early start in industrialization.[180][182] Overall, China is a net importer of greenhouse emissions.[183]

The targets laid out in China's nationally determined contribution in 2016 will likely be met, but are not enough to properly combat global warming.[184] China has committed to peak emissions by 2030 and net zero by 2060.[185] In order to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C coal plants in China without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[186] China continues to build coal-fired power stations in 2020 and promised to "phase down" coal use from 2026.[187] According to various analysis, China is estimated to overachieve its renewable energy capacity and emission reduction goals early, but long-term plans are still required to combat the global climate change and meeting the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets.[188][189][190]India

Greenhouse gas emissions by India are the third largest in the world and the main source is coal.[191] India emitted 2.8 Gt of CO2eq in 2016 (2.5 including LULUCF).[192][193] 79% were CO2, 14% methane and 5% nitrous oxide.[193] India emits about 3 gigatonnes (Gt) CO2eq of greenhouse gases each year; about two tons per person,[194] which is half the world average.[195] The country emits 7% of global emissions.[196]

As of 2019[update] these figures are quite uncertain, but a comprehensive greenhouse gas inventory is within reach.[197] Cutting greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore air pollution in India, would have health benefits worth 4 to 5 times the cost, which would be the most cost-effective in the world.[198]

The Paris Agreement commitments included a reduction of this intensity by 33–35% by 2030.[199] India's annual emissions per person are less than the global average,[200] and the UNEP forecasts that by 2030 they will be between 3 and 4 tonnes.[196]

In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GhG, followed by the US with 11%, then India with 6.6%.[201]

The Indian national carbon trading scheme may be created in 2023.Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Climate change mitigation (or decarbonisation) is action to limit the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that cause climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions are primarily caused by people burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. Phasing out fossil fuel use can happen by conserving energy and replacing fossil fuels with clean energy sources such as wind, hydro, solar, and nuclear power. Secondary mitigation strategies include changes to land use and removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. Governments have pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but actions to date are insufficient to avoid dangerous levels of climate change.[202]

Solar energy and wind power have the greatest potential for supplanting fossil fuels at the lowest cost compared to other options.[203] The availability of sunshine and wind is variable and can require electrical grid upgrades, such as using long-distance electricity transmission to group a range of power sources.[204] Energy storage can also be used to even out power output, and demand management can limit power use when power generation is low. Cleanly generated electricity can usually replace fossil fuels for powering transportation, heating buildings, and running industrial processes. Certain processes are more difficult to decarbonise, such as air travel and cement production. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) can be an option to reduce net emissions in these circumstances, although fossil fuel power plants with CCS technology have not yet proven economical.[205]Fiscal decentralisation and carbon reductions

As carbon oxides are one important source of greenhouse gas, having means to reduce it is important. One suggestion, is to consider some means in relation to fiscal decentralisation. Previous research found that the linear term of fiscal decentralization promotes carbon emissions, while the non-linear term mitigates it.[clarification needed] It verified the inverted U-shaped curve between fiscal decentralization and carbon emissions.[example needed] Besides, increasing energy prices for non-renewable energy decrease carbon emission due to a substitution effect. Among other explanatory variables, improvement in the quality of institutions decreases carbon emissions, while the gross domestic product increases it. Strengthening fiscal decentralization, lowering non-renewable energy prices,[clarification needed] and improving institutional quality to check the deteriorating environmental quality in the study sample and other worldwide regions can reduce carbon emissions.[206]

Effect of policy

This section needs to be updated. (December 2019) |

Governments have taken action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate climate change. Assessments of policy effectiveness have included work by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, International Energy Agency,[207][208] and United Nations Environment Programme.[209] Policies implemented by governments have included[210][211][212] national and regional targets to reduce emissions, promoting energy efficiency, and support for a renewable energy transition, such as Solar energy, as an effective use of renewable energy because solar uses energy from the sun and does not release pollutants into the air.

Countries and regions listed in Annex I of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (i.e., the OECD and former planned economies of the Soviet Union) are required to submit periodic assessments to the UNFCCC of actions they are taking to address climate change.[212]: 3

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a significant reduction in CO2 emissions globally in 2020.

Projections

A climate change scenario is a hypothetical future based on a "set of key driving forces".[213]: 1812 Scenarios explore the long-term effectiveness of mitigation and adaptation.[214] Scenarios help to understand what the future may hold. They can show which decisions will have the most meaningful effects on mitigation and adaptation.

Closely related to climate change scenarios are pathways, which are more concrete and action-oriented. However, in the literature, the terms scenarios and pathways are often used in a way that they mean the same thing.[215]: 9

Many parameters influence climate change scenarios. Three important parameters are the number of people (and population growth), their economic activity new technologies. Economic and energy models, such as World3 and POLES, quantify the effects of these parameters.

Climate change scenarios exist at a national, regional or global scale. Countries use scenario studies in order to better understand their decisions. This is useful when they are developing their adaptation plans or Nationally Determined Contributions. International goals for mitigating climate change like the Paris Agreement are based on studying these scenarios. For example, the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C was a "key scientific input" into the 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference.[216] Various pathways are considered in the report, describing scenarios for mitigation of global warming. Pathways include for example portfolios for energy supply and carbon dioxide removal.See also

- Attribution of recent climate change

- Carbon accounting

- Carbon credit

- Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center

- Carbon offset

- Carbon tax

- Green hydrogen

- List of countries by renewable electricity production

- Low-carbon economy

- Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2

- Paris Agreement

- Perfluorotributylamine

- Vehicle emission standard

- World energy supply and consumption

- Zero-emissions vehicle

References

- ^ ● "Territorial (MtCO2)". GlobalCarbonAtlas.org. Retrieved 30 December 2021. (choose "Chart view"; use download link)

● Data for 2020 is also presented in Popovich, Nadja; Plumer, Brad (12 November 2021). "Who Has The Most Historical Responsibility for Climate Change?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021.

● Source for country populations: "List of the populations of the world's countries, dependencies, and territories". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. - ^ "Annual CO₂ emissions". Our World in Data. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (11 May 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b "Chapter 2: Emissions trends and drivers" (PDF). Ipcc_Ar6_Wgiii. 2022.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (4 April 2022). "IPCC: Climate Change 2022, Mitigation of Climate Change, Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). ipecac.ch. Retrieved 22 April 2004.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (11 May 2020). "Greenhouse gas emissions". Our World in Data. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "By 2030, Cut Per Capita Emission to Global Average: India to G20". The Leading Solar Magazine In India. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ PBL (21 December 2020). "Trends in Global CO2 and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions; 2020 Report". PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ IPCC (2019). "Summary for Policy Makers" (PDF). IPCC: 99.

- ^ a b c Grubb, M. (July–September 2003). "The economics of the Kyoto protocol" (PDF). World Economics. 4 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- ^ Lerner & K. Lee Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth (2006). "Environmental issues: essential primary sources". Thomson Gale. Retrieved 11 September 2006.

- ^ Johnston, Chris; Milman, Oliver; Vidal, John (15 October 2016). "Climate change: global deal reached to limit use of hydrofluorocarbons". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "Climate change: 'Monumental' deal to cut HFCs, fastest growing greenhouse gases". BBC News. 15 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ "Nations, Fighting Powerful Refrigerant That Warms Planet, Reach Landmark Deal". The New York Times. 15 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b Bader, N.; Bleichwitz, R. (2009). "Measuring urban greenhouse gas emissions: The challenge of comparability". S.A.P.I.EN.S. 2 (3). Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ "Transcript: The Path Forward: Al Gore on Climate and the Economy". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Banuri, T. (1996). Equity and social considerations. In: Climate change 1995: Economic and social dimensions of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.P. Bruce et al. Eds.). This version: Printed by Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, and New York. PDF version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0521568548.

- ^ World energy outlook 2007 edition – China and India insights. International Energy Agency (IEA), Head of Communication and Information Office, 9 rue de la Fédération, 75739 Paris Cedex 15, France. 2007. p. 600. ISBN 978-9264027305. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Holtz-Eakin, D. (1995). "Stoking the fires? CO2 emissions and economic growth" (PDF). Journal of Public Economics. 57 (1): 85–101. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(94)01449-X. S2CID 152513329.

- ^ "Selected Development Indicators" (PDF). World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change (PDF). Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 2010. Tables A1 and A2. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-7987-5. ISBN 978-0821379875.

- ^ Dodman, David (April 2009). "Blaming cities for climate change? An analysis of urban greenhouse gas emissions inventories". Environment and Urbanization. 21 (1): 185–201. doi:10.1177/0956247809103016. ISSN 0956-2478. S2CID 154669383.

- ^ "Analysis: When might the world exceed 1.5C and 2C of global warming?". Carbon Brief. 4 December 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "World now likely to hit watershed 1.5 °C rise in next five years, warns UN weather agency". UN News. 26 May 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Nishat (14 June 2021). "G7 countries agree to existing climate change policies". Open Access Government. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Tollefson, Jeff (9 August 2021). Helmuth, Laura (ed.). "Earth Is Warmer Than It's Been in 125,000 Years". Scientific American. Berlin: Springer Nature. ISSN 0036-8733. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Fox, Alex. "Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Reaches New High Despite Pandemic Emissions Reduction". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "The present carbon cycle – Climate Change". Grida.no. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Climate Change: Causation Archives". EarthCharts. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "It's critical to tackle coal emissions – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (12 January 2016). "Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock's long shadow (Report). FAO Livestock, Environment and Development (LEAD) Initiative.

- ^ Ciais, Phillipe; Sabine, Christopher; et al. "Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles" (PDF). In Stocker Thomas F.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. IPCC. p. 473.

- ^ a b Raupach, M.R.; et al. (2007). "Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO2 emissions" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104 (24): 10288–93. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410288R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700609104. PMC 1876160. PMID 17519334.

- ^ "Global Methane Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities" (PDF). Global Methane Initiative. 2020.

- ^ "Sources of methane emissions". International Energy Agency. 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Key facts and findings". Fao.org. Food and Agricultural Organization. n.d. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Chrobak, Ula (14 May 2021). "Fighting climate change means taking laughing gas seriously". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-051321-2. S2CID 236555111. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions, study says". The Guardian. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Gustin, Georgina (9 July 2017). "25 Fossil Fuel Producers Responsible for Half Global Emissions in Past 3 Decades". Inside Climate News. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ a b "IPCC Working Group III – Mitigation of Climate Change, Annex III: Technology - specific cost and performance parameters - Table A.III.2 (Emissions of selected electricity supply technologies (gCO 2eq/kWh))" (PDF). IPCC. 2014. p. 1335. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "IPCC Working Group III – Mitigation of Climate Change, Annex II Metrics and Methodology - A.II.9.3 (Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions)" (PDF). pp. 1306–1308. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity Generation Options | UNECE". unece.org. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ "The 660 MW plant should be considered as an outlier, as transportation for the dam construction elements is assumed to occur over thousands of kilometers (which is only representative of a very small share of hydropower projects globally). The 360 MW plant should be considered as the most representative, with fossil greenhouse gas emissions ranging from 6.1 to 11 g CO2eq/kWh" (UNECE 2020 section 4.4.1)

- ^ "Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle" (PDF). Epa.gov. US Environment Protection Agency. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (1 November 2006). "How gasoline becomes CO2, Slate Magazine". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ "Volume calculation for carbon dioxide". Icbe.com. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Hilgers, Michael (2020). The Diesel Engine, in series: commercial vehicle technology. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-60856-2.

- ^ "Voluntary Reporting of Greenhouse Gases Program". Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original on 1 November 2004. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Olivier & Peters 2020, p. 4

- ^ Global Carbon Budget 2020

- ^ a b "Methane vs. Carbon Dioxide: A Greenhouse Gas Showdown". One Green Planet. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ IGSD (2013). "Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs)". Institute of Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD). Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Zaelke, Durwood; Borgford-Parnell, Nathan; Andersen, Stephen; Picolotti, Romina; Clare, Dennis; Sun, Xiaopu; Gabrielle, Danielle (2013). "Primer on Short-Lived Climate Pollutants" (PDF). Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development. p. 3.

- ^ using 100 year global warming potential from IPCC-AR4

- ^ Dreyfus, Gabrielle B.; Xu, Yangyang; Shindell, Drew T.; Zaelke, Durwood; Ramanathan, Veerabhadran (31 May 2022). "Mitigating climate disruption in time: A self-consistent approach for avoiding both near-term and long-term global warming". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (22): e2123536119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11923536D. doi:10.1073/pnas.2123536119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9295773. PMID 35605122. S2CID 249014617.

- ^ a b Olivier & Peters 2020, p. 20

- ^ Lombrana, Laura Millan; Warren, Hayley; Rathi, Akshat (2020). "Measuring the Carbon-Dioxide Cost of Last Year's Worldwide Wildfires". Bloomberg L.P.

- ^ Global fire annual emissions (PDF) (Report). Global Fire Emissions Database.

- ^ a b c Olivier & Peters 2020, p. 6

- ^ a b c d Olivier & Peters 2020, p. 12

- ^ Olivier & Peters 2020, p. 23

- ^ World Meteorological Organization (January 2019). "Scientific Assessment of ozone Depletion: 2018" (PDF). Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project. 58: A3 (see Table A1).

- ^ Thompson, R.L; Lassaletta, L.; Patra, P.K (2019). "Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion". Nature Climate Change. 9 (12). et al.: 993–998. Bibcode:2019NatCC...9..993T. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0613-7. S2CID 208302708.

- ^ Olivier & Peters 2020, p. 38

- ^ Bond; et al. (2013). "Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment". J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118 (11): 5380–5552. Bibcode:2013JGRD..118.5380B. doi:10.1002/jgrd.50171.

- ^ Ramanathan, V.; Carmichael, G. (April 2008). "Global and regional climate changes due to black carbon". Nature Geoscience. 1 (4): 221–227. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..221R. doi:10.1038/ngeo156.

- ^ "Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector". EarthCharts. 6 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Climate Watch". www.climatewatchdata.org. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ IEA, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018: Highlights (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2018) p.98

- ^ IEA, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018: Highlights (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2018) p.101

- ^ "The World's Biggest Emitter of Greenhouse Gases". Bloomberg.com. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Nabuurs, G-J.; Mrabet, R.; Abu Hatab, A.; Bustamante, M.; et al. "Chapter 7: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU)" (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. p. 750. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.009..

- ^ Steinfeld H, Gerber P, Wassenaar T, Castel V, Rosales M, de Haan C (2006). Livestock's long shadow: environmental issues and options (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.

- ^ FAO (2020). Emissions due to agriculture. Global, regional and country trends 2000–2018 (PDF) (Report). FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series. Vol. 18. Rome. p. 2. ISSN 2709-0078.

- ^ Section 4.2: Agriculture's current contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, in: HLPE (June 2012). Food security and climate change. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. pp. 67–69. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014.

- ^ Sarkodie, Samuel A.; Ntiamoah, Evans B.; Li, Dongmei (2019). "Panel heterogeneous distribution analysis of trade and modernized agriculture on CO2 emissions: The role of renewable and fossil fuel energy consumption". Natural Resources Forum. 43 (3): 135–153. doi:10.1111/1477-8947.12183. ISSN 1477-8947.

- ^ "Carbon emissions from fertilizers could be reduced by as much as 80% by 2050". Science Daily. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "How livestock farming affects the environment". www.downtoearth.org.in. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Friel, Sharon; Dangour, Alan D.; Garnett, Tara; et al. (2009). "Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: food and agriculture". The Lancet. 374 (9706): 2016–2025. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61753-0. PMID 19942280. S2CID 6318195.

- ^ "The carbon footprint of foods: are differences explained by the impacts of methane?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme (2022). Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window — Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies. Nairobi.

- ^ "Bovine Genomics | Genome Canada". www.genomecanada.ca. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Airhart, Ellen. "Canada Is Using Genetics to Make Cows Less Gassy". Wired – via www.wired.com.

- ^ "The use of direct-fed microbials for mitigation of ruminant methane emissions: a review".

- ^ Parmar, N.R.; Nirmal Kumar, J.I.; Joshi, C.G. (2015). "Exploring diet-dependent shifts in methanogen and methanotroph diversity in the rumen of Mehsani buffalo by a metagenomics approach". Frontiers in Life Science. 8 (4): 371–378. doi:10.1080/21553769.2015.1063550. S2CID 89217740.

- ^ "Kowbucha, seaweed, vaccines: the race to reduce cows' methane emissions". The Guardian. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ Boadi, D (2004). "Mitigation strategies to reduce enteric methane emissions from dairy cows: Update review". Can. J. Anim. Sci. 84 (3): 319–335. doi:10.4141/a03-109.

- ^ Martin, C. et al. 2010. Methane mitigation in ruminants: from microbe to the farm scale. Animal 4 : pp 351-365.

- ^ Eckard, R. J.; et al. (2010). "Options for the abatement of methane and nitrous oxide from ruminant production: A review". Livestock Science. 130 (1–3): 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2010.02.010.

- ^ Davidson, Jordan (4 September 2020). "Aviation Accounts for 3.5% of Global Warming Caused by Humans, New Research Says". Ecowatch. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ a b Ürge-Vorsatz, Diana; Khosla, Radhika; Bernhardt, Rob; Chan, Yi Chieh; Vérez, David; Hu, Shan; Cabeza, Luisa F. (2020). "Advances Toward a Net-Zero Global Building Sector". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45: 227–269. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-045843.

- ^ "Why the building sector?". Architecture 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Budds, Diana (19 September 2019). "How do buildings contribute to climate change?". Curbed. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Sequestering Carbon in Buildings". Green Energy Times. 23 June 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "IPCC — Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Freitag, Charlotte; Berners-Lee, Mike (December 2020). "The climate impact of ICT: A review of estimates, trends and regulations". arXiv:2102.02622 [physics.soc-ph].

- ^ "The computer chip industry has a dirty climate secret". the Guardian. 18 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Working from home is erasing carbon emissions -- but for how long?". Grist. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Cunliff, Colin (6 July 2020). "Beyond the Energy Techlash: The Real Climate Impacts of Information Technology".

- ^ J. Eckelman, Matthew; Huang, Kaixin; Dubrow, Robert; D. Sherman, Jodi (December 2020). "Health Care Pollution And Public Health Damage In The United States: An Update". Health Affairs. 39 (12): 2071–2079. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01247. PMID 33284703.

- ^ Tsaia, I-Tsung; Al Alia, Meshayel; El Waddi, Sanaâ; Adnan Zarzourb, aOthman (2013). "Carbon Capture Regulation for The Steel and Aluminum Industries in the UAE: An Empirical Analysis". Energy Procedia. 37: 7732–7740. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.719. ISSN 1876-6102. OCLC 5570078737.

- ^ "Emissions". www.iea.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ "We have too many fossil-fuel power plants to meet climate goals". Environment. 1 July 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ "March: Tracking the decoupling of electricity demand and associated CO2 emissions". www.iea.org. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Grant, Don; Zelinka, David; Mitova, Stefania (13 July 2021). "Reducing CO2 emissions by targeting the world's hyper-polluting power plants". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (9): 094022. Bibcode:2021ERL....16i4022G. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac13f1. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Emission Trends and Drivers, Ch 2 in "Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change" https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/

- ^ Zheng, Jiajia; Suh, Sangwon (May 2019). "Strategies to reduce the global carbon footprint of plastics". Nature Climate Change. 9 (5): 374–378. Bibcode:2019NatCC...9..374Z. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0459-z. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 145873387.

- ^ "The Link Between Plastic Use and Climate Change: Nitty-gritty". stanfordmag.org. 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

... According to the EPA, approximately one ounce of carbon dioxide is emitted for each ounce of polyethylene (PET) produced. PET is the type of plastic most commonly used for beverage bottles. ...'

- ^ Glazner, Elizabeth (21 November 2017). "Plastic Pollution and Climate Change". Plastic Pollution Coalition. Plastic Pollution Coalition. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Blue, Marie-Luise. "What Is the Carbon Footprint of a Plastic Bottle?". Sciencing. Leaf Group Ltd. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Royer, Sarah-Jeanne; Ferrón, Sara; Wilson, Samuel T.; Karl, David M. (1 August 2018). "Production of methane and ethylene from plastics in the environment". PLOS ONE. 13 (Plastic, Climate Change): e0200574. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300574R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200574. PMC 6070199. PMID 30067755.

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (2 August 2018). "Study Finds New Reason to Ban Plastic: It Emits Methane in the Sun". No. Plastic, Climate Change. Ecowatch. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ "Sweeping New Report on Global Environmental Impact of Plastics Reveals Severe Damage to Climate". Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). Retrieved 16 May 2019.