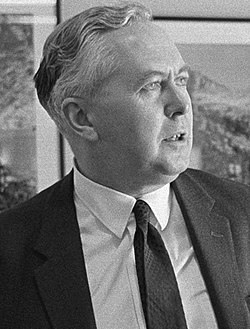

Harold Wilson

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2007) |

Harold Wilson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 4 March, 1974 – 5 April, 1976 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Edward Heath |

| Succeeded by | James Callaghan |

| In office 10 October 1964 – 19 June 1970 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Alec Douglas-Home |

| Succeeded by | Edward Heath |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 11 March 1916 Huddersfield, United Kingdom |

| Died | 24 May 1995 (aged 79) London, United Kingdom |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse | Mary Baldwin |

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Oxford |

| Profession | Academic |

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, PC (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was one of the most prominent British politicians of the 20th century. He emerged as Prime Minister after more General Elections than any other 20th century Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, with majorities of 4 in 1964, 98 in 1966 and 5 in October 1974, and with enough seats to form a minority government in February 1974. He is the most recent British Prime Minister to serve non-consecutive terms.

Harold Wilson first served as prime minister in the 1960's, during a period of low unemployment and relative economic prosperity (though also of significant problems with the UK's external balance of payments). His second term in office occurred during the seventies, when a period of economic crisis was beginning to hit most Western countries. On both occasions, economic concerns were to prove a significant constraint on his governments' ambitions. Although originating from the left wing of the Labour Party, Wilson's brand of socialism placed emphasis on promoting social justice (including through better educational opportunities), allied to the technocratic aim of taking better advantage of rapid scientific progress, rather than on the left's traditional goal of promoting wider public ownership of industry. While he did not challenge the Party constitution's stated dedication to nationalization head-on, he took little action to pursue it either, suggesting that he may have viewed some of the old ideas of the Left as being of limited relevance. Wilson managed a number of difficult political issues with considerable tactical skill, but his ambition of substantially improving Britain's long-term economic performance remained largely unfulfilled.

Early life

Wilson was born in Huddersfield, England in 1916, an almost exact contemporary of his rival, Edward Heath (b. 9 July 1916). He came from a political family: his father Herbert (1882–1971) was a works chemist who had been active in the Liberal Party and then joined the Labour Party. His mother Ethel (née Seddon; 1882–1957) was a schoolteacher prior to her marriage. When Wilson was eight, he visited London and a later-to-be-famous photograph was taken of him standing on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street.

Education

Wilson won a scholarship to attend the local grammar school, Royds Hall Secondary School, Huddersfield. His education was disrupted in 1931 when he contracted typhoid fever after drinking contaminated milk on a Scouts' outing and took months to recover. The next year his father, working as an industrial chemist, was made redundant and moved to Spital on the Wirral to find work. Wilson attended the sixth form at the Wirral Grammar School for Boys, where he became Head Boy.

Wilson did well at school and, although he missed getting a scholarship, he obtained an exhibition which when topped up by a county grant enabled him to study Modern History at Jesus College, Oxford from 1934. At Oxford, Wilson was moderately active in politics as a member of the Liberal Party but was later influenced by G. D. H. Cole to join the Labour Party. After his first year, he changed his field of study to Philosophy, Politics and Economics. He graduated with "an outstanding First Class degree, with alphas on every paper."[1], gaining 17 alpha marks out of a possible total of 18 in the final examinations. He also received exceptional testimonials from his tutors, including a comment from one that 'he is, far and away, the ablest man I have taught so far'.

Wilson "graduated from Jesus College, Oxford in 1937 with a bachelor's degree,"[2] having "read Modern History (he)...changed to PPE...had two abortive attempts at an All Souls Fellowship...came under the eye of Sir William Beveridge, who from the Directorship of the LSE, had just become Master of University College, Oxford...took Wilson on as a research assistant...Wilson taught Economics at Jesus College...from 1937."[3] He continued in academia, becoming one of the youngest Oxford University dons of the century at the age of 21. He was a lecturer in Economic History at University College from 1938 (and was a fellow of that college 1938–45). For much of this time, he was a research assistant to William Beveridge, the Master of the College, working on the issues of unemployment and the trade cycle.

Marriage

In 1940, in the chapel of Mansfield College, Oxford, he married (Gladys) Mary Baldwin who remained his wife until his death. Mary Wilson became a published poet. They had two sons, Robin and Giles; Robin became a Professor of Mathematics, and Giles became a teacher. In November 2006 it was reported that Giles had given up his teaching job and become a train driver for South West Trains.[4]

Wartime service

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Wilson volunteered for service but was classed as a specialist and moved into the Civil Service instead. Most of his War was spent as a statistician and economist for the coal industry. He was Director of Economics and Statistics at the Ministry of Fuel and Power 1943–4.

He was to remain passionately interested in statistics. As President of the Board of Trade, he was the driving force behind the Statistics of Trade Act 1947, which is still the authority governing most economic statistics in Great Britain. He was instrumental as Prime Minister in appointing Claus Moser as head of the Central Statistical Office, and was President of the Royal Statistical Society in 1972–73.

Member of Parliament

As the War drew to an end, he searched for a seat to fight at the impending general election. He was selected for Ormskirk, then held by Stephen King-Hall. Wilson accidentally agreed to be adopted as the candidate immediately rather than delay until the election was called, and was therefore compelled to resign from the Civil Service. He used the time in between to write A New Deal for Coal which used his wartime experience to argue for nationalisation of the coal mines on the basis of improved efficiency.

In the 1945 general election, Wilson won his seat in line with the Labour landslide. To his surprise, he was immediately appointed to the government as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Works. Two years later, he became Secretary for Overseas Trade, in which capacity he made several official trips to the Soviet Union to negotiate supply contracts. Conspiracy-minded critics would later seek to raise suspicions about these trips.

In government

On 14 October 1947, Wilson was appointed President of the Board of Trade and, at 31, became the youngest member of the Cabinet in the 20th century. He took a lead in abolishing some of the wartime rationing, which he referred to as a "bonfire of controls". In the general election of 1950, his constituency was altered and he was narrowly elected for the new seat of Huyton.

Wilson was becoming known as a left-winger and joined Aneurin Bevan in resigning from the government in April 1951 in protest at the introduction of National Health Service (NHS) medical charges to meet the financial demands imposed by the Korean War. After the Labour Party lost the general election later that year, he was made chairman of Bevan's "Keep Left" group, but shortly thereafter he distanced himself from Bevan. By coincidence, it was Bevan's further resignation from the Shadow Cabinet in 1954 that put Wilson back on the front bench.

Opposition

Wilson soon proved a very effective Shadow Minister. One of his procedural moves caused the loss of the Government's Finance Bill in 1955, and his speeches as Shadow Chancellor from 1956 were widely praised for their clarity and wit. He coined the term "gnomes of Zurich" to describe Swiss bankers whom he accused of pushing the pound down by speculation. In the meantime, he conducted an inquiry into the Labour Party's organisation following its defeat in the 1955 general election, which compared the Party organization to an antiquated "penny farthing" bicycle, and made various recommendations for improvements. Unusually, Wilson combined the job of Chairman of the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee with that of Shadow Chancellor from 1959 , holding the chairmanship of the PAC from 1959 to 1963.

Wilson steered a course in intra-party matters in the 1950s and early 1960s that left him fully accepted and trusted by neither the left nor the right. Despite his earlier association with the left-of-centre Aneurin Bevan, in 1955 he backed the right-of-centre Hugh Gaitskell against Bevan for the party leadership [5] He then launched an opportunistic but unsuccessful challenge to Gaitskell in 1960, in the wake of the Labour Party's 1959 defeat, Gaitskell's controversial attempt to ditch Labour's commitment to nationalisation in the shape of the Party's Clause Four, and Gaitskell's defeat at the 1960 Party Conference over a motion supporting Britain's unilateral nuclear disarmament. Wilson also challenged for the deputy leadership in 1962 but was defeated by George Brown. Following these challenges, he was moved to the position of Shadow Foreign Secretary.

Hugh Gaitskell died unexpectedly in January 1963, just as the Labour Party had begun to unite and to look to have a good chance of being elected to government. Wilson became the left candidate for the leadership. He defeated George Brown, who was hampered by a reputation as an erratic figure, in a straight contest in the second round of balloting, after James Callaghan, who had entered the race as an alternative to Brown on the right of the party, had been eliminated in the first round.

Wilson's 1964 election campaign was aided by the Profumo Affair, a 1963 ministerial sex scandal that had mortally wounded the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan and was to taint his successor Sir Alec Douglas-Home, even though Home had not been involved in the scandal. Wilson made capital without getting involved in the less salubrious aspects. (Asked for a statement on the scandal, he reportedly said "No comment... in glorious Technicolor!"). Home was an aristocrat who had given up his title as Lord Home to sit in the House of Commons. To Wilson's comment that he was the fourteenth Earl of Home, Home retorted "I suppose Mr. Wilson is the fourteenth Mr. Wilson".

At the Labour Party's 1963 annual conference, Wilson made possibly his best-remembered speech, on the implications of scientific and technological change, in which he argued that "the Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated measures on either side of industry". This speech did much to set Wilson's reputation as a technocrat not tied to the prevailing class system.

Prime Minister

Labour won the 1964 general election with a narrow majority of four seats, and Wilson became Prime Minister. This was an insufficient parliamentary majority to last for a full term, and after 18 months, a second election in March 1966 returned Wilson with the much larger majority of 96.

Economic policies

In economic terms, Wilson's first three years in office were dominated by an ultimately doomed effort to stave off the devaluation of the pound. He inherited an unusually large external deficit on the balance of trade. This partly reflected the preceding government's expansive fiscal policy in the run-up to the 1964 election, and the incoming Wilson team tightened the fiscal stance in response. Many British economists advocated devaluation, but Wilson resisted, reportedly in part out of concern that Labour, which had previously devalued sterling in 1949, would become tagged as "the party of devaluation".

After a costly battle, market pressures forced the government into devaluation in 1967. Wilson was much criticized for a broadcast in which he assured listeners that the "pound in your pocket" had not lost its value. It was widely forgotten that his next sentence had been "prices will rise". Economic performance did show some improvement after the devaluation, as economists had predicted.

A main theme of Wilson's economic approach was to place enhanced emphasis on "indicative economic planning." He created a new Department of Economic Affairs to generate ambitious targets that were in themselves supposed to help stimulate investment and growth. Though now out of fashion, faith in this approach was at the time by no means confined to the Labour Party -- Wilson built on foundations that had been laid by his Conservative predecessors, in the shape, for example, of the National Economic Development Council (known as "Neddy") and its regional counterparts (the "little Neddies").

The continued relevance of industrial nationalisation (a centerpiece of the post-War Labour government's programme) had been a key point of contention in Labour's internal struggles of the 1950s and early 1960s. Wilson's predecessor as leader, Hugh Gaitskell, had tried in 1960 to tackle the controversy head-on, with a proposal to expunge Clause Four (the public ownership clause) from the party's constitution, but had been forced to climb down. Wilson took a characteristically more subtle approach. He threw the party's left wing a symbolic bone with the renationalisation of the steel industry, but otherwise left Clause Four formally in the constitution but in practice on the shelf.

Wilson made periodic attempts to mitigate inflation through wage-price controls, better known in the UK as "prices and incomes policy". Partly as a result, the government tended to find itself repeatedly injected into major industrial disputes, with late-night "beer and sandwiches at Number Ten" an almost routine culmination to such episodes. Among the more damaging of the numerous strikes during Wilson's periods in office was a six-week stoppage by the National Union of Seamen, beginning shortly after Wilson's re-election in 1966. With public frustration over strikes mounting, Wilson's government in 1969 proposed a series of reforms to the legal basis for industrial relations (labour law) in the UK, which were outlined in a White Paper entitled "In Place of Strife". Following a confrontation with the Trades Union Congress, however, which strongly opposed the proposals, the government substantially backed-down from its proposals. Some elements of these reforms were subsequently to be revived (in modified form) as a centerpiece of the premiership of Margaret Thatcher.

External affairs

Overseas, while Britain's retreat from Empire had by 1964 already progressed a long way (and was to continue during his terms in office), Wilson was troubled by a major crisis over the future of the British crown colony of Rhodesia. Wilson refused to concede official independence to the Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith, who led a white minority government which resisted extending the vote to the majority black population. Smith in response proclaimed Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence on November 11, 1965. Wilson was applauded by most nations for taking a firm stand on the issue (and none extended diplomatic recognition to the Smith regime). He declined, however, to intervene in Rhodesia with military force, believing the UK population would not support such action against their "kith and kin". Smith subsequently attacked Wilson in his memoirs, accusing him of delaying tactics during negotiations and alleging duplicity; Wilson responded in kind, questioning Smith's good faith and suggesting that Smith had moved the goal-posts whenever a settlement appeared in sight.

Despite considerable pressure from US President Lyndon Johnson for at least a token involvement of British military units in the Vietnam War, Wilson consistently avoided such a commitment of British forces. His government offered some rhetorical support for the US position (most prominently in the defense offered by then-Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart in a much-publicized "teach in" or debate on Vietnam), and on at least one occasion made an unsuccessful effort to intermediate in the conflict. On 28 June 1966 Wilson 'dissociated' his Government from Johnson's bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong. From a contemporary viewpoint, some commentators have attached new significance to Wilson's ability to maintain close relations with the US while pursuing an independent line on Vietnam, in light of the different approach taken by the Blair government which resulted in Britain's participation in the Iraq War (2003).

In 1967, Wilson's Government lodged the UK's second application to join the European Economic Community. Like the first, made under Harold Macmillan, it was vetoed by the French President Charles de Gaulle.

That same year, Wilson announced that Britain would withdraw its military forces from major bases 'East of Suez', effectively bringing Britain's empire to an end and marking a major shift in Britain's global defence strategy in the twentieth century.

Social issues

Wilson's period in office witnessed a range of social reforms, including abolition of capital punishment, decriminalisation of male homosexual acts between consenting adults in private, liberalisation of abortion law, divorce reform and abolition of theatre censorship. Such reforms were mostly adopted on non-party votes, but the large Labour majority after 1966 was undoubtedly more open to such changes than previous parliaments had been. Wilson personally, coming culturally from a provincial non-conformist background, showed no particular enthusiasm for much of this agenda (which some linked to the "permissive society"), but the reforming climate was especially encouraged by Roy Jenkins during his period at the Home Office.

Wilson's 1966-70 term witnessed growing public concern over the level of immigration to the United Kingdom. The issue was dramatised at the political level by the famous "Rivers of Blood speech" by the Conservative politician Enoch Powell, warning against the dangers of immigration, which led to Powell's dismissal from the Shadow Cabinet. Wilson's government adopted a two-track approach. While condemning racial discrimination (and adopting legislation to make it a legal offense), Wilson's Home Secretary James Callaghan introduced significant new restrictions on the right of immigration to the United Kingdom.

Education policies

Education held special significance for a socialist of Wilson's generation, in view of its role both in opening up opportunities for children from working class backgrounds and enabling the UK to seize the potential benefits of scientific advances. Wilson continued the rapid creation of new universities, in line with the recommendations of the Robbins Report, a bipartisan policy already in train when Labour took power. Alas, the economic difficulties of the period deprived the tertiary system of the resources it needed. However, university expansion remained a core policy. One notable effect was the first entry of women into university education in significant numbers.

Wilson also deserves credit for grasping the concept of an Open University, to give adults who had missed out on tertiary education a second chance through part-time study and distance learning. His political commitment included assigning implementation responsibility to Baroness Jennie Lee, the widow of Labour's iconic left-wing tribune Aneurin Bevan.

Wilson's record on secondary education is, by contrast, highly controversial. A fuller description is in the article Education in England. Two factors played a role. Following the Education Act 1944 there was disaffection with the tripartite system of academically-oriented Grammar schools for a small proportion of "gifted" children, and Technical and Secondary Modern schools for the majority of children. Pressure grew for the abolition of the selective principle underlying the "eleven plus", and replacement with Comprehensive schools which would serve the full range of children (see the article Debates on the grammar school). Comprehensive education became Labour Party policy.

Labour pressed local authorities to convert grammar schools, many of them cherished local institutions, into comprehensives. Conversion continued on a large scale during the subsequent Conservative Heath administration, although the Secretary of State, Mrs Margaret Thatcher, ended the compulsion of local governments to convert. While the proclaimed goal was to level school quality up, many felt that the grammar schools' excellence was being sacrificed with little to show in the way of improvement of other schools. Critically handicapping implementation, economic austerity meant that schools never received sufficient funding.

A second factor affecting education was change in teacher training, including introduction of "progressive" child-centered methods, abhorred by many established teachers. In parallel, the profession became increasingly politicised. The status of teaching suffered and is still recovering.

Few nowadays question the unsatisfactory nature of secondary education in 1964. Change was overdue. However, the manner in which change was carried out is certainly open to criticism. The issue became a priority for ex-Education Secretary Margaret Thatcher when she came to office as prime minister in 1979.

In 1966, Wilson was created the first Chancellor of the newly created University of Bradford, a position he held until 1985.

Electoral defeat and return to office

By 1969, the Labour Party was suffering serious electoral reverses. In May 1970, Wilson responded to an apparent recovery in his government's popularity by calling a general election, but, to the surprise of most observers, was defeated at the polls by the Conservatives under Edward Heath.

Wilson survived as leader of the Labour party in opposition. Economic conditions during the 1970s were becoming more difficult for the UK and many other western economies, and the Heath government in its turn was buffeted by economic adversity and industrial unrest (notably including confrontation with the coalminers). When Labour won more seats than the Conservative Party in February 1974, and Heath was unable to form a coalition, Wilson returned to 10 Downing Street as Prime Minister of a minority Labour Government. He gained a majority in another election shortly afterwards, in October 1974.

EC Membership Renegotiations and Referendum

Among the most challenging political dilemmas Wilson faced in opposition and on his return to power was the issue of British membership of the European Community (EC), which had been negotiated by the Heath administration following de Gaulle's fall from power in France. The Labour party was deeply divided on the issue, and risked a major split. Wilson showed political ingenuity in devising a position that both sides of the party could agree on. Labour's manifesto in 1974 thus included a pledge to renegotiate terms for Britain's membership and then hold a referendum (a constitutional procedure without precedent in British history) on whether to stay in the EC on the new terms.

The renegotiations with Britain's fellow EC members focused primarily on Britain's net budgetary contribution to the EC. As a small agricultural producer heavily dependent on imports, the UK suffered doubly from the dominance of (i) agricultural spending in the EU budget, and (ii) agricultural import taxes as a source of EU revevues. During the renegotiations, other EU members conceded, as a partial offset, the establishment of a significant European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), from which it was clearly agreed that the UK would be a major net beneficiary. [6] In the subsequent referendum campaign, rather than the normal British tradition of "collective responsibility", whereby the government takes a policy position which all cabinet members are required to support publicly, members of the Government were free to present their views on either side of the question. A referendum was duly held on 5 June 1975. In the event, continued membership passed.

Northern Ireland

In the late 1960s, Wilson's government witnessed the outbreak of The Troubles in Northern Ireland. In response to a request from the government of the province, the government agreed to deploy the British army in an effort to maintain the peace.

Out of office in the autumn of 1971, Wilson formulated a 16-point, 15 year program that was designed to pave the way for the unification of Ireland. The proposal was welcomed in principle by the Heath government at the time, but never put into effect.

In May 1974, he condemned the Unionist-controlled Ulster Workers' Strike as a "sectarian strike" which was "being done for sectarian purposes having no relation to this century but only to the seventeenth century". However he refused to pressure a reluctant British Army to face down the loyalist paramilitaries who were intimidating utility workers. In a later television speech he referred to the "loyalist" strikers and their supporters as "spongers" who expected Britain to pay for their lifestyles. The strike was eventually successful in breaking the power-sharing Northern Ireland executive.

Resignation

On 16 March 1976, Wilson surprised the nation by announcing his resignation as Prime Minister. He claimed that he had always planned on resigning at the age of sixty, and that he was physically and mentally exhausted. As early as the late 1960s, he had been telling intimates, like his doctor Sir Joseph Stone (later Lord Stone of Hendon), that he did not intend to serve more than eight or nine years as Prime Minister. However, by 1976 he was probably also aware of the first stages of early-onset Alzheimer's disease, as both his formerly excellent memory and powers of concentration began to fail dramatically.

Queen Elizabeth II came to dine at 10 Downing Street to mark his resignation, an honour she has bestowed on only one other Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill (although she did dine at Downing Street at Tony Blair's invitation, to celebrate her 80th birthday).

Wilson's resignation honours list included many businessmen and celebrities, along with his political supporters. It caused lasting damage to his reputation when it was revealed that the first draft of the list had been written by Marcia Williams on lavender notepaper (it became known as The Lavender List). Some of those whom Wilson honoured included Lord Kagan, eventually imprisoned for fraud, and Sir Eric Miller, who later committed suicide while under police investigation for corruption.

Tony Benn, James Callaghan, Anthony Crosland, Michael Foot, Denis Healey and Roy Jenkins stood in the first ballot to replace him. Jenkins was initially tipped as the favourite but came third on the initial ballot. In the final ballot on 5 April, Callaghan defeated Foot in a parliamentary vote of 176 to 137, thus becoming Wilson's successor as Prime Minister and leader of the Labour Party.

As Wilson wished to remain an MP after leaving office, he was not immediately given the peerage customarily offered to retired Prime Ministers, but instead was created a Knight of the Garter. On leaving the House of Commons in 1983, he was created Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, after Rievaulx Abbey, in the north of his native Yorkshire.

Death

Not long after Wilson's retirement, his mental deterioration from Alzheimer's disease began to be apparent, and he rarely appeared in public after 1987. He died of colon cancer in May 1995, at the age of 79. He is buried on St Mary's, Isles of Scilly. His epitaph is Tempus Imperator Rerum (Time Commands All Things). His memorial service was held in Westminster Abbey on 13 July.

Political "style"

Wilson regarded himself as a "man of the people" and did much to promote this image, contrasting himself with the stereotypical aristocratic conservatives who had preceded him. Features of this portrayal included his working man's Gannex raincoat, his pipe (though in private he smoked cigars), his love of simple cooking and overuse of the popular British relish, 'HP Sauce', his support for his home town's football team, Huddersfield, and his working-class Yorkshire accent. Eschewing continental holidays, he returned every summer with his family to the Isles of Scilly. His first general election victory relied heavily on associating these down-to-earth attributes with a sense that the UK urgently needed to modernise, after "thirteen years of Tory mis-rule....". These characteristics were exaggerated in Private Eye's satirical column Mrs Wilson's Diary.

Wilson exhibited his populist touch in 1965 when he had The Beatles honoured with the award of MBE. (Such awards are officially bestowed by The Queen but are nominated by the Prime Minister of the day.) The award was popular with young people and contributed to a sense that the Prime Minister was "in touch" with the younger generation. There were some protests by conservatives and elderly members of the military who were earlier recipients of the award, but such protesters were in the minority. Critics claimed that Wilson acted to solicit votes for the next general election (which took place less than a year later), but defenders noted that, since the mimimum voting age at that time was 21, this was hardly likely to impact many of the Beatles' fans who at that time were predominantly teenagers. It did however cement Wilson's image as a modernistic leader and linked him to the burgeoning pride in the 'New Britain' typified by the Beatles.

One year later, in 1967, Wilson had a different interaction with a musical ensemble. He sued the pop group The Move for libel after the band's manager Tony Secunda published a promotional postcard for the single Flowers In The Rain, featuring a caricature depicting Wilson in bed with his female assistant, Marcia Falkender (later Baroness Falkender). Wild gossip had hinted at an improper relationship, though these rumours were never substantiated. Wilson won the case, and all royalties from the song (composed by Move leader Roy Wood) were assigned in perpetuity to a charity of Wilson's choosing.

Wilson had a knack for memorable phrases. He coined the term "Selsdon Man" to refer to the anti-interventionist policies of the Conservative leader Edward Heath, developed at a policy retreat held at the Selsdon Park Hotel in early 1970. This phrase, intended to evoke the "primitive throwback" qualities of anthropological discoveries such as Piltdown Man and Swanscombe Man, was part of a British political tradition of referring to political trends by suffixing man. Another famous quote is "A week is a long time in politics": this signifies that political fortunes can change extremely rapidly. Other memorable phrases attributed to Wilson include "the white heat of the [technological] revolution" and his comment after the 1967 devaluation of the pound: "This does not mean that the pound here in Britain — in your pocket or purse — is worth any less....", usually now quoted as "the pound in your pocket".

Reputation

Despite his successes and onetime popularity, Harold Wilson's reputation has yet to recover substantially from its low ebb following his second premiership. Some accuse him of inordinate deviousness, some claim he did not do enough to modernise the Labour Party's policy positions on issues such as the respective roles of the state and the market or the reform of industrial relations. This line of argument partly blames Wilson for the civil unrest of the late 1970s (during Britain's Winter of Discontent), and for the electoral success of the Conservative party and its ensuing 18-year rule. His supporters argue that it was only Wilson's own skillful management (on issues such as nationalisation, Europe and Vietnam) that allowed an otherwise fractious party to stay politically united and govern. In either case this co-existence did not long survive his leadership, and the factionalism that followed contributed greatly to the Labour Party's low ebb during the 1980s. For many voters, Thatcherism emerged politically as the only alternative [see TINA] to the excesses of trade-union power. Meanwhile, the reinvention of the Labour Party would take the better part of two decades, at the hands of Neil Kinnock, John Smith and Tony Blair.

In 1964, when Wilson took office, the mainstream of informed opinion (in all the main political parties, in academia and the media, etc.) strongly favored the type of technocratic, "indicative planning" approach that Wilson endeavored to implement. Radical market-oriented reforms, of the kind eventually adopted by Margaret Thatcher, were in the mid-1960s backed only by a "fringe" of enthusiasts (such as the leadership of the later-influential Institute of Economic Affairs), and had almost no representation at senior levels even of the Conservative Party. Fifteen years later, disillusionment with Britain's weak economic performance and the unsatisfactory state of industrial relations, combined with active spadework by figures such as Sir Keith Joseph, had helped to make a radical market programme politically feasible for Margaret Thatcher (which was in turn to influence the subsequent Labour leadership, especially under Tony Blair). To suppose that Wilson could have adopted such a line in the late 1960s or early 1970s is, however, anachronistic: like almost any political leader, Wilson was fated to work (sometimes skillfully and successfully, sometimes not) with the ideas that were in the air at the time.

Discussion of Possible Plots and Conspiracy Theories

MI5 plots?

In 1963, Soviet defector Anatoliy Golitsyn is said to have secretly claimed that Wilson was a KGB agent. [7] The majority of intelligence officers did not believe that Golitsyn was a genuine defector but a significant number did (most prominently James Jesus Angleton, the Deputy Director of Counter-Intelligence at the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and factional strife broke out between the two groups. The book Spycatcher (an exposé of MI5) alleged that 30 MI5 agents then collaborated in an attempt to undermine Wilson. The author Peter Wright (a former member of MI5) later claimed that his ghostwriter had written 30 when he had meant 3. Many of Wright's claims are controversial, and a ministerial statement reported that an internal investigation failed to find any evidence to support the allegations.

Several other voices beyond Wright have raised claims of "dirty tricks" on the part of elements within the intelligence services against Wilson while he was in office. In March 1987, James Miller, a former MI5 agent, claimed that MI5 had encouraged the Ulster Workers' Council general strike in 1974 in order to destabilise Wilson's Government. See also: Walter Walker and David Stirling. In July 1987, Labour MP Ken Livingstone used his maiden speech to raise the 1975 allegations of a former Army Press officer in Northern Ireland, Colin Wallace, who also alleged a plot to destabilise Wilson. Chris Mullin, MP, speaking on 23rd of November, 1988, argued that sources other than Peter Wright supported claims of a long-standing attempt by the intelligence services (MI5) to undermine Wilson's government [8]

A BBC programme The Plot Against Harold Wilson, broadcast in 2006, reported that, in tapes recorded soon after his resignation on health grounds, Wilson stated that for 8 months of his premiership he didn't "feel he knew what was going on, fully, in security". Wilson alleged two plots, in the late 1960s and mid 1970s respectively. He said that plans had been hatched to install Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Prince Charles, Prince of Wales's uncle and mentor, as interim Prime Minister (see also Other conspiracy theories, below). He also claimed that ex-military leaders had been building up private armies in anticipation of "wholesale domestic liquidation".

In the documentary some of Wilson's allegations received partial confirmation in interviews with ex-intelligence officers and others, who reported that, on two occasions during Wilson's terms in office, they had talked about a possible coup to take over the government.

On a separate track, elements within MI5 had also, the BBC programme reported, spread "black propaganda" that Wilson and Williams were Soviet agents, and that Wilson was an IRA sympathiser, apparently with the intention of helping the Conservatives win the 1974 election.

Other conspiracy theories

Richard Hough, in his 1980 biography of Mountbatten, indicates that Mountbatten was in fact approached during the 1960s in connection with a scheme to install an "emergency government" in place of Wilson's administration. The approach was made by Cecil Harmsworth King, the chairman of the International Printing Corporation (IPC), which published the Daily Mirror newspaper. Hough bases his account on conversations with the Mirror's long-time editor Hugh Cudlipp, supplemented by the recollections of the scientist Solly Zuckerman and of Mountbatten’s valet, William Evans. Cudlipp arranged for Mountbatten to meet King on 8 May 1968. King had long yearned to play a more central political role, and had personal grudges against Wilson (including Wilson's refusal to propose King for the hereditary earldom that King coveted). He had already failed in an earlier attempt to replace Wilson with James Callaghan. With Britain's continuing economic difficulties and industrial strife in the 1960s, King convinced himself that Wilson's government was heading towards collapse. He thought that Mountbatten, as a Royal and a former Chief of the Defence Staff, would command public support as leader of a non-democratic "emergency" government. Mountbatten insisted that his friend, Zuckerman, be present (Zuckerman says that he was urged to attend by Mountbatten’s son-in-law, Lord Brabourne, who worried King would lead Mountbatten astray). King asked Mountbatten if he would be willing to head an emergency government. Zuckerman said the idea was treachery and Mountbatten in turn rebuffed King. He does not, however, appear to have reported the approach to Downing Street.

The question of how serious a threat to democracy may have existed during these years continues to be controversial -- a key point at issue being who of any consequence would have been ready to move beyond grumbling about the government (or spreading rumours) to actively taking unconstitutional action. Cecil King himself was an inveterate schemer but an inept actor on the political stage. Perhaps significantly, when King penned a strongly worded editorial against Wilson for the Daily Mirror two days after his abortive meeting with Mountbatten, the unanimous reaction of IPC's directors was to fire him with immediate effect from his position as Chairman. More fundamentally, Denis Healey, who served for six years as Wilson's Secretary of State for Defence, has argued that actively serving senior British military officers would not have been prepared to overthrow a constitutionally-elected government. By the time of his resignation, Wilson's own perceptions of any threat may have been exacerbated by the onset of Alzheimer's; his inherent tendency to suspiciousness was undoubtedly stoked by some in his inner circle, notably including Marcia Williams.

Files released on 1 June 2005 show that Wilson was concerned that, while on the Isles of Scilly, he was being monitored by Russian ships disguised as trawlers. MI5 found no evidence of this, but told him not to use a walkie-talkie.)

Wilson's Government took strong action against the controversial, self-styled Church of Scientology in 1967, banning foreign Scientologists from entering the UK (a prohibition which remained in force until 1980). In response, L. Ron Hubbard, Scientology's founder, accused Wilson of being in cahoots with Soviet Russia and an international conspiracy of psychiatrists and financiers. Wilson's Minister of Health, Kenneth Robinson, subsequently won a libel suit against the Church and Hubbard.

Harold Wilson's first government, October 1964 - June 1970

Initial Cabinet

- Harold Wilson - Prime Minister

- George Brown - First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Economic Affairs

- Lord Gardiner - Lord Chancellor

- Herbert Bowden - Lord President of the Council

- Lord Longford - Lord Privy Seal

- James Callaghan - Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Patrick Gordon Walker - Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Sir Frank Soskice - Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Fred Peart - Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food

- Anthony Greenwood - Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Arthur Bottomley - Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- Denis Healey - Secretary of State for Defence

- Michael Stewart - Secretary of State for Education and Science

- Richard Crossman - Minister of Housing and Local Government

- Barbara Castle - Minister for Overseas Development

- Ray Gunter - Minister of Labour

- Douglas Houghton - Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Frederick Lee - Minister of Power

- William Ross - Secretary of State for Scotland

- Frank Cousins - Minister of Technology

- Douglas Jay - President of the Board of Trade

- Thomas Fraser - Minister of Transport

- Jim Griffiths - Secretary of State for Wales

- Margaret Herbison - Minister of Pensions and National Insurance

Changes

- January 1965 - Michael Stewart succeeds Patrick Gordon Walker as Foreign Secretary. Anthony Crosland succeeds Stewart as Education Secretary.

- December 1965 - Barbara Castle succeeds Thomas Fraser as Minister of Transport. Anthony Greenwood succeeds Castle as Minister of Overseas Development. Lord Longford succeeds Greenwood as Colonial Secretary. Sir Frank Soskice succeeds Lord Longford as Lord Privy Seal. Roy Jenkins succeeds Soskice as Home Secretary.

- April 1966 - Lord Longford succeeds Sir Frank Soskice as Lord Privy Seal. Frederick Lee succeeds Longford as Colonial Secretary. Richard Marsh succeeds Lee as Minister of Power. Douglas Houghton resigns as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. His successor is not in the cabinet. Cledwyn Hughes succeeds Jim Griffiths as Welsh Secretary.

- July 1966 - Tony Benn succeeds Frank Cousins as Minister of Technology.

After reshuffle, August 1966

- Harold Wilson - Prime Minister

- Michael Stewart - First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Economic Affairs

- Lord Gardiner - Lord Chancellor

- Richard Crossman - Lord President of the Council

- Lord Longford - Lord Privy Seal

- James Callaghan - Chancellor of the Exchequer

- George Brown - Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Roy Jenkins - Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Fred Peart - Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food

- Herbert Bowden - Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs

- Denis Healey - Secretary of State for Defence

- Anthony Crosland - Secretary of State for Education and Science

- Anthony Greenwood - Minister of Housing and Local Government

- Arthur Bottomley - Minister for Overseas Development

- Ray Gunter - Minister of Labour

- Richard Marsh - Minister of Power

- William Ross - Secretary of State for Scotland

- Tony Benn - Minister of Technology

- Douglas Jay - President of the Board of Trade

- Barbara Castle - Minister of Transport

- Cledwyn Hughes - Secretary of State for Wales

Changes

- January 1967 - Lord Shackleton and Patrick Gordon Walker enter the cabinet as Ministers without Portfolio.

- August 1967 - Peter Shore succeeds Michael Stewart as Secretary of State for Economic Affairs. Stewart remains First Secretary of State. George Thomson succeeds Herbert Bowden as Commonwealth Secretary. Anthony Crosland succeeds Douglas Jay as President of the Board of Trade. Patrick Gordon Walker succeeds Anthony Crosland as Education Secretary. Arthur Bottomley, Minister of Overseas Development, leaves the cabinet. His successor in that office is not in the cabinet.

- November 1967 - Roy Jenkins succeeds James Callaghan as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Callaghan succeeds Jenkins as Home Secretary

- January 1968 - Lord Shackleton succeeds Lord Longford as Lord Privy Seal.

After reshuffle, April 1968

- Harold Wilson - Prime Minister

- Barbara Castle - First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity

- Lord Gardiner - Lord Chancellor

- Richard Crossman - Lord President of the Council

- Fred Peart - Lord Privy Seal

- Roy Jenkins - Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Peter Shore - Secretary of State for Economic Affairs

- Michael Stewart - Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- James Callaghan - Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Cledwyn Hughes - Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food

- George Thomson - Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs

- Denis Healey - Secretary of State for Defence

- Edward Short - Secretary of State for Education and Science

- Anthony Greenwood - Minister of Housing and Local Government

- Ray Gunter - Minister of Labour

- Ray Gunter - Minister of Power

- William Ross - Secretary of State for Scotland

- Tony Benn - Minister of Technology

- Anthony Crosland - President of the Board of Trade

- Richard Marsh - Minister of Transport

- George Thomas - Secretary of State for Wales

- Lord Shackleton - Paymaster General

Changes

- July 1968 - Roy Mason succeeds Ray Gunter as Minister of Power.

- October-November 1968 - Fred Peart succeeds Richard Crossman as Lord President. Lord Shackleton succeeds Fred Peart as Lord Privy Seal. Judith Hart succeeds Shackleton as Paymaster-General. The Foreign and Commonwealth Offices are merged, with Michael Stewart as Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary. Jack Diamond, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, enters the cabinet. The office of Secretary of State for Social Services is created, with Richard Crossman as Secretary. George Thomson enters the cabinet as Minister without Portfolio.

- October 1969 - Anthony Greenwood, Minister of Housing and Local Government, leaves the cabinet. George Thomson becomes Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Anthony Crosland, becomes the Secretary of State for Local Government and Regional Planning. Roy Mason succeeds Crosland as President of the Board of Trade. His previous position of Minister of Power is abolished. Harold Lever succeeds Judith Hart as Paymaster General. Richard Marsh resigns as Minister of Transport. His successor is not in the cabinet.

Harold Wilson's second government, March 1974 - April 1976

- Harold Wilson - Prime Minister

- Lord Elwyn-Jones - Lord Chancellor

- Edward Short - Lord President of the Council

- Lord Shepherd - Lord Privy Seal

- Denis Healey - Chancellor of the Exchequer

- James Callaghan - Foreign Secretary

- Roy Jenkins - Home Secretary

- Fred Peart - Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food

- Roy Mason - Secretary of State for Defence

- Reginald Prentice - Secretary of State for Education and Science

- Michael Foot - Secretary of State for Employment

- Eric Varley - Secretary of State for Energy

- Anthony Crosland - Secretary of State for the Environment

- Barbara Castle - Secretary of State for Health and Social Security

- Tony Benn - Secretary of State for Industry

- Harold Lever - Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Merlyn Rees - Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

- William Ross - Secretary of State for Scotland

- Shirley Williams - Secretary of State for Prices and Consumer Protection

- Peter Shore - Secretary of State for Trade

- John Morris - Secretary of State for Wales

- Robert Mellish - Chief Whip

Changes

- October 1974 - John Silkin although working to the Secretary of State for Environment enters the cabinet as Minister of Planning and Local Government.

- June 1975 - Fred Mulley succeeds Reginald Prentice as Secretary for Education and Science. Prentice becomes Secretary for Overseas Development. Tony Benn succeeds Eric Varley as Secretary for Energy. Varley succeeds Benn as Secretary for Industry.

Titles from birth to death

- Harold Wilson, Esq (11 March 1916–1 January 1945)

- Harold Wilson, Esq, OBE (1 January 1945–26 July 1945)

- Harold Wilson, Esq, OBE, MP (26 July 1945–29 September 1947)

- The Right Honourable Harold Wilson, OBE, MP (29 September 1947–6 December 1969)

- The Right Honourable Harold Wilson, OBE, FRS, MP (6 December 1969–23 April 1976)

- The Right Honourable Sir Harold Wilson, KG, OBE, FRS, MP (23 April 1976–9 June 1983)

- The Right Honourable Sir Harold Wilson, KG, OBE, FRS (9 June–16 September 1983)

- The Right Honourable The Lord Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, PC, OBE, FRS (16 September 1983–24 May 1995)

Wilson on television

- Shortly after resigning as Prime Minister Wilson was signed by David Frost to host a series of interview/chat show programmes. The pilot episode proved to be a flop as Wilson appeared uncomfortable with the informality of the format.

- Wilson also hosted two editions of the BBC chat show 'Friday Night, Saturday Morning'. He famously floundered in the role, and in 2000, Channel 4 chose it as one of the 100 Moments of TV Hell.

- In 1978, Harold Wilson appeared on the Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special. Eric Morecambe's habit of appearing not to recognise the guest stars was repaid by Wilson, who referred to him throughout as 'Mor-e-cam-by'.

- Francis Wheen scripted the BBC Four 2006 drama The Lavender List, a fictional account of the Wilson Government of 1974–76. Kenneth Cranham played Wilson, Gina McKee Marcia Williams and Celia Imrie has a supporting role as Wilson's wife. The play concentrated on Wilson and Williams' relationship and her conflict with the Downing Street Press Secretary Joe Haines.

- Also in 2006, The Plot Against Harold Wilson aired on BBC Two at 2100GMT on Thursday 16 March. The drama/documentary detailed previously unseen evidence that rogue elements of MI5 and the British military plotted to take down the Labour Government, believing Wilson to be a Soviet spy. Harold Wilson was portrayed by James Bolam.

Trivia

- A popular urban myth at Oxford University states that Wilson's grade in his final examination was the highest ever recorded up to that date.

- Wilson was a supporter of Huddersfield Town Football Club[9]

- Wilson was an Honorary Fellow of Columbia Pacific University [1]. This was at a time when CPU was led by a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and two former presidents of regionally accredited schools. The former British Prime Minister also delivered a speech at a CPU graduation ceremony [2].

- Wilson was voted Pipe Smoker of the Year in 1965 and Pipeman of the Decade in 1976 by the British Pipesmokers' Council.

- Both Wilson and Edward Heath are named in the lyrics of the George Harrison song "Taxman" the lead track from the Revolver album by The Beatles.

- A viking in the Asterix story Asterix and the Great Crossing is named Haraldwilssen, and shares his physical features.

Bibliography

There is an extensive bibliography on Harold Wilson. He is the author of a number of books. He is the subject of many biographies (both light and serious) and academic analyses of his career and various aspects of the policies pursued by the governments he has led. He features in many "humorous" books. He was the Prime Minister in the so-called "Swinging London" era of the 1960s, and therefore features in many of the books about this period of history.

For an extensive list of titles, see the article Harold Wilson: Bibliography.

Notes

- ^ Ben Pimlott, Harold Wilson, London: Harper-Collins, 1993, p.59

- ^ "James Harold Wilson". Archontology.org. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ^ Moore, Peter G (1996). "Obituary: James Harold Wilson 1916-95". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society). Vol. 159 (1): pp. 165–173. ISSN 0964-1998. OCLC 42017027. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysummary=,|laydate=,|laysource=,|month=, and|quotes=(help) - ^ "Son of former PM Harold Wilson swaps teaching for a career as train driver". Gordon Rayner. /www.dailymail.co.uk. 2006-09-19. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Geoffrey Goodman (25 May 1995). "Harold Wilson: Leading Labour beyond pipe dreams". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Andrew Moravcsik, "The Choice for Europe" (Cornell, 1998)

- ^ Vasili Mitrokhin, Christopher Andrew (2000). The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. Gardners Books. ISBN 0-14-028487-7.

- ^ House of Commons Handard Debates for 23 Nov 1988

- ^ "A 2012 Chance for David Beckham?", OhMy News International Sports, 16 January 2007

See also

External links

- Wilson, Harold Chronology World History Database

- More about Harold Wilson on the Downing Street website.

- Roy Hattersley, The truth about Harold Wilson - after 30 years of scandalous rumours, Daily Mail, 24th June 2007

- 1916 births

- 1995 deaths

- Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- Leaders of the British Labour Party

- Cold War leaders

- Labour MPs (UK)

- UK MPs 1945-1950

- UK MPs 1950-1951

- UK MPs 1951-1955

- UK MPs 1955-1959

- UK MPs 1959-1964

- UK MPs 1964-1966

- UK MPs 1966-1970

- UK MPs 1970-1974

- UK MPs 1974

- UK MPs 1974-1979

- UK MPs 1979-1983

- Members of the United Kingdom Parliament for English constituencies

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Presidents of the Royal Statistical Society

- Fellows of University College, Oxford

- British civil servants

- Alumni of Jesus College, Oxford

- Chancellors of the University of Bradford

- Knights of the Garter

- Life peers

- People from Huddersfield

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- Deaths from Alzheimer's disease

- English Congregationalists

- Colorectal cancer deaths