Himalayas: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 173.246.222.66 to version by Webclient101. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1437149) (Bot) |

Tag: possible vandalism |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

{{main|Ecology of the Himalaya}} |

{{main|Ecology of the Himalaya}} |

||

The flora and fauna of the Himalayas vary with climate, rainfall, altitude, and soils. The climate ranges from tropical at the base of the mountains to permanent ice and snow at the highest elevations. Owing to the mountains’ latitude near the [[Tropic of Cancer]], the permanent [[snow line]] is among the highest in the world at typically around {{convert|5500|m|ft|-2}}.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shi|first1=Yafeng|last2=Xie|first2=Zizhu|last3=Zheng|first3=Benxing|last4=Li|first4=Qichun|url=http://itia.ntua.gr/hsj/redbooks/126/iahs_126_0111.pdf|title=Distribution, Feature and Variations of Glaciers in China|journal=World Glacier Inventory|year=1978|publisher=Riederalp Workshop}}</ref> In contrast, [[equator]]ial mountains in [[New Guinea]], the [[Rwenzoris]] and [[Colombia]] have a snow line some {{convert|900|m|ft|-1}} lower.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Henderson-Sellers|first1=Ann|last2=McGuffie|first2=Kendal|title=The Future of the World's Climate: A Modelling Perspective|pages=199-201|isbn=9780123869173}}</ref> The amount of yearly rainfall increases from west to east along the southern front of the range. This diversity of altitude, rainfall and soil conditions combined with the very high snow line supports a variety of distinct plant and animal communities. For example the extremes of high altitude (low atmospheric pressure) combined with extreme cold allow [[extremophile]] organisms to survive.<ref>{{cite web|first=C. Michael|last=Hogan|year=2010|url=http://www.eoearth.org/article/Archaea?topic=49496|title=Archaea|editor1-first=E.|editor1-last=Monosson|editor2-first=C.|editor2-last=Cleveland|work=Encyclopedia of Earth|publisher=National Council for Science and the Environment|location Washington DC}}</ref> |

The flora and fauna of the Himalayas vary with climate, rainfall, altitude, and soils. The climate ranges from tropical at the base of the mountains to permanent ice and snow at the highest elevations. Owing to the mountains’ latitude near the [[Tropic of Cancer]], the permanent [[snow line]] is among the highest in the world at typically around {{convert|5500|m|ft|-2}}.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shi|first1=Yafeng|last2=Xie|first2=Zizhu|last3=Zheng|first3=Benxing|last4=Li|first4=Qichun|url=http://itia.ntua.gr/hsj/redbooks/126/iahs_126_0111.pdf|title=Distribution, Feature and Variations of Glaciers in China|journal=World Glacier Inventory|year=1978|publisher=Riederalp Workshop}}</ref> In contrast, [[equator]]ial mountains in [[New Guinea]], the [[Rwenzoris]] and [[Colombia]] have a snow line some {{convert|900|m|ft|-1}} lower.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Henderson-Sellers|first1=Ann|last2=McGuffie|first2=Kendal|title=The Future of the World's Climate: A Modelling Perspective|pages=199-201|isbn=9780123869173}}</ref> The amount of yearly rainfall increases from west to east along the southern front of the range. This diversity of altitude, rainfall and soil conditions combined with the very high snow line supports a variety of distinct plant and animal communities. For example the extremes of high altitude (low atmospheric pressure) combined with extreme cold allow [[extremophile]] organisms to survive.<ref>{{cite web|first=C. Michael|last=Hogan|year=2010|url=http://www.eoearth.org/article/Archaea?topic=49496|title=Archaea|editor1-first=E.|editor1-last=Monosson|editor2-first=C.|editor2-last=Cleveland|work=Encyclopedia of Earth|publisher=National Council for Science and the Environment|location Washington DC}}</ref> |

||

THIS is not an accurate site! |

|||

The unique floral and faunal wealth of the Himalayas is undergoing structural and compositional changes due to [[climate change]]. The increase in temperature may shift various species to higher elevations. The oak forest is being invaded by pine forests in the Garhwal Himalayan region. There are reports of early flowering and fruiting in some tree species, especially [[rhododendron]], [[apple]] and ''[[Myrica esculenta]]''. The highest known tree species in the Himalayas is ''Juniperus tibetica'' located at {{convert|4900|m|ft|-1}} in Southeastern Tibet.<ref name>{{cite journal|url=http://www.uni-marburg.de/fb19/personal/professoren/miehe/pdfs/20074.pdf|title=Highest Treeline in the Northern Hemisphere Found in Southern Tibet|first1=Georg|last1=Miehe|first2=Sabine|last2=Miehe|first3=Jonas|last3=Vogel|first4=Sonam|last4=Co|first5=La|last5=Duo|year=2004|journal=Mountain Research and Development|volume=27|issue=2|date=May 2007|pages=169–173|doi=10.1659/mrd.0792}}</ref> |

The unique floral and faunal wealth of the Himalayas is undergoing structural and compositional changes due to [[climate change]]. The increase in temperature may shift various species to higher elevations. The oak forest is being invaded by pine forests in the Garhwal Himalayan region. There are reports of early flowering and fruiting in some tree species, especially [[rhododendron]], [[apple]] and ''[[Myrica esculenta]]''. The highest known tree species in the Himalayas is ''Juniperus tibetica'' located at {{convert|4900|m|ft|-1}} in Southeastern Tibet.<ref name>{{cite journal|url=http://www.uni-marburg.de/fb19/personal/professoren/miehe/pdfs/20074.pdf|title=Highest Treeline in the Northern Hemisphere Found in Southern Tibet|first1=Georg|last1=Miehe|first2=Sabine|last2=Miehe|first3=Jonas|last3=Vogel|first4=Sonam|last4=Co|first5=La|last5=Duo|year=2004|journal=Mountain Research and Development|volume=27|issue=2|date=May 2007|pages=169–173|doi=10.1659/mrd.0792}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:57, 10 January 2013

| Himalayas | |

|---|---|

The north face of Mount Everest as seen from the path to the base camp in Tibet Autonomous Region, People's Republic of China. | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Everest, Nepal and China |

| Elevation | 8,848 m (29,029 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 2,400 km (1,500 mi) |

| Geography | |

Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 526: Unable to find the specified location map definition: "Module:Location map/data/Himalayas Map.png" does not exist.

| |

| Countries | Afghanistan, Bhutan, Burma, China, India, Nepal and Pakistan |

The Himalayas, also Himalaya, (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˌhɪməˈleɪ.ə/ or /hɪˈmɑːləjə/; Sanskrit, hima (snow) + ālaya (dwelling), literally, "abode of the snow"[1]) is a mountain range in Asia separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau.

The Himalayan range is home to some of the planet's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. The Himalayas include over a hundred mountains exceeding 7,200 metres (23,600 ft) in height. By contrast, the highest peak outside Asia—Aconcagua, in the Andes— is 6,961 metres (22,838 ft) tall.[2] The Himalayas have profoundly shaped the cultures of South Asia. Many Himalayan peaks are sacred in both Hinduism and Buddhism.

Besides the Greater Himalaya of these high peaks there are parallel lower ranges. The first foothills reaching about a thousand meters along the northern edge of the plains are called the Sivalik Hills or Sub-Himalayan Range. Further north is a higher range reaching two to three thousand meters known as the Lower Himalayan or Mahabharat Range.

The Himalayas abut or cross five countries: Bhutan, India, Nepal, People's Republic of China, and Pakistan, with the first three countries having sovereignty over most of the range.[3] The Himalayas are bordered on the northwest by the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges, on the north by the Tibetan Plateau, and on the south by the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

Three of the world's major rivers, the Indus, the Ganges, and the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra all rise near Mount Kailash to cross and encircle the Himalayas. Their combined drainage basin is home to some 600 million people.

Lifted by the subduction of the Indian tectonic plate under the Eurasian Plate, the Himalayan range runs, west-northwest to east-southeast, in an arc 2,400 kilometres (1,500 mi) long. Its western anchor, Nanga Parbat, lies just south of the northernmost bend of Indus river, its eastern anchor, Namcha Barwa, just west of the great bend of the Tsangpo river. The range varies in width from 400 kilometres (250 mi) in the west to 150 kilometres (93 mi) in the east.

Ecology

The flora and fauna of the Himalayas vary with climate, rainfall, altitude, and soils. The climate ranges from tropical at the base of the mountains to permanent ice and snow at the highest elevations. Owing to the mountains’ latitude near the Tropic of Cancer, the permanent snow line is among the highest in the world at typically around 5,500 metres (18,000 ft).[4] In contrast, equatorial mountains in New Guinea, the Rwenzoris and Colombia have a snow line some 900 metres (2,950 ft) lower.[5] The amount of yearly rainfall increases from west to east along the southern front of the range. This diversity of altitude, rainfall and soil conditions combined with the very high snow line supports a variety of distinct plant and animal communities. For example the extremes of high altitude (low atmospheric pressure) combined with extreme cold allow extremophile organisms to survive.[6] THIS is not an accurate site! The unique floral and faunal wealth of the Himalayas is undergoing structural and compositional changes due to climate change. The increase in temperature may shift various species to higher elevations. The oak forest is being invaded by pine forests in the Garhwal Himalayan region. There are reports of early flowering and fruiting in some tree species, especially rhododendron, apple and Myrica esculenta. The highest known tree species in the Himalayas is Juniperus tibetica located at 4,900 metres (16,080 ft) in Southeastern Tibet.[7]

Geology

The Himalayas are among the youngest mountain ranges on the planet and consist mostly of uplifted sedimentary and metamorphic rock. According to the modern theory of plate tectonics, their formation is a result of a continental collision or orogeny along the convergent boundary between the Indo-Australian Plate and the Eurasian Plate. This is referred to as a fold mountain.

The collision began in the Upper Cretaceous period about 70 million years ago, when the north-moving Indo-Australian Plate, moving at about 15 cm per year, collided with the Eurasian Plate. About 50 million years ago, this fast moving Indo-Australian plate had completely closed the Tethys Ocean, the existence of which has been determined by sedimentary rocks settled on the ocean floor, and the volcanoes that fringed its edges. Since these sediments were light, they crumpled into mountain ranges rather than sinking to the floor. The Indo-Australian plate continues to be driven horizontally below the Tibetan plateau, which forces the plateau to move upwards. The Arakan Yoma highlands in Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal were also formed as a result of this collision.

The Indo-Australian plate is still moving at 67 mm per year, and over the next 10 million years it will travel about 1,500 km into Asia. About 20 mm per year of the India-Asia convergence is absorbed by thrusting along the Himalaya southern front. This leads to the Himalayas rising by about 5 mm per year, making them geologically active. The movement of the Indian plate into the Asian plate also makes this region seismically active, leading to earthquakes from time to time.

Hydrology

The Himalayan range encompasses about 15,000 glaciers, which store about 12,000 km3 (3000 cubic miles) of fresh water.[citation needed] Its glaciers include the Gangotri and Yamunotri (Uttarakhand) and Khumbu glaciers (Mount Everest region), and Zemu (Sikkim).

The higher regions of the Himalayas are snowbound throughout the year, in spite of their proximity to the tropics, and they form the sources of several large perennial rivers, most of which combine into two large river systems:

- The western rivers combine into the Indus Basin, of which the Indus River is the largest. The Indus begins in Tibet at the confluence of Sengge and Gar rivers and flows southwest through India and then through Pakistan to the Arabian Sea. It is fed by the Jhelum, the Chenab, the Ravi, the Beas, and the Sutlej rivers, among others.

- Most of the other Himalayan rivers drain the Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin. Its main rivers are the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Yamuna, as well as other tributaries. The Brahmaputra originates as the Yarlung Tsangpo River in western Tibet, and flows east through Tibet and west through the plains of Assam. The Ganges and the Brahmaputra meet in Bangladesh, and drain into the Bay of Bengal through the world's largest river delta.[8]

The easternmost Himalayan rivers feed the Ayeyarwady River, which originates in eastern Tibet and flows south through Myanmar to drain into the Andaman Sea.

The Salween, Mekong, Yangtze and Huang He (Yellow River) all originate from parts of the Tibetan plateau that are geologically distinct from the Himalaya mountains, and are therefore not considered true Himalayan rivers. Some geologists refer to all the rivers collectively as the circum-Himalayan rivers.[9] In recent years, scientists have monitored a notable increase in the rate of glacier retreat across the region as a result of global climate change.[10] For example, Glacial lakes have been forming rapidly on the surface of the debris-covered glaciers in the Bhutan Himalaya during the last few decades. Although the effect of this will not be known for many years, it potentially could mean disaster for the hundreds of millions of people who rely on the glaciers to feed the rivers of northern India during the dry seasons.[11]

Lakes

The Himalayan region is dotted with hundreds of lakes. Most lakes are found at altitudes of less than 5,000 m, with the size of the lakes diminishing with altitude. Pangong Tso, which is spread across the border between India and China, and Yamdrok Tso, located in central Tibet, are amongst the largest with surface areas of 700 km², and 638 km², respectively. Other notable lakes include Gurudogmar lake in North Sikkim, Tsongmo lake, near the Indo-China border in Sikkim, and Tilicho lake in Nepal in the Annapurna massif.

The mountain lakes are known to geographers as tarns if they are caused by glacial activity. Tarns are found mostly in the upper reaches of the Himalaya, above 5,500 metres.[12]

Impact on climate

The Himalayas have a profound effect on the climate of the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan plateau. They prevent frigid, dry Arctic winds blowing south into the subcontinent, which keeps South Asia much warmer than corresponding temperate regions in the other continents. It also forms a barrier for the monsoon winds, keeping them from traveling northwards, and causing heavy rainfall in the Terai region. The Himalayas are also believed to play an important part in the formation of Central Asian deserts, such as the Taklamakan and Gobi.[13]

Religion

In Hinduism, the Himalaya have also been personified as the god Himavat, the God of snow, who is mentioned in the Mahabharata. He is father of Ganga and Saraswati, who became rivers, and Parvati, who married Shiva[14]

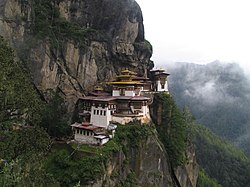

Several places in the Himalaya are of religious significance in Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism. A notable example of a religious site is Paro Taktsang, where Padmasambhava is said to have founded Buddhism in Bhutan.[15]

A number of Tibetan Buddhist sites are situated in the Himalaya, including the residence of the Dalai Lama. There were over 6,000 monasteries in Tibet.[16] The Tibetan Muslims had their own mosques in Lhasa and Shigatse.[17]

See also

- Geography of Nepal

- List of mountains in Nepal

- Lo Manthang

- List of Ultras of the Eastern Himalayas

- List of Himalayan topics

- List of Himalayan peaks

- List of Himalayan passes and routes

- American Himalayan Foundation

- Baltistan

- Digital Himalaya

- Eastern Himalaya

- Eight-thousander – a list of peaks over 8,000 metres

- Geography of China

- Geography of India

- Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan

- Himalayan Peaks of Uttarakhand

- Himalayan Towers

- Indian Himalayan Region

- Indian Network on Climate Change Assessment

- Karakoram (mountain range)

- Karakoram Highway

- Ladakh

- List of mountains in Pakistan

- Mountain ranges of Pakistan

- Seven years in Tibet (film)

- Trekking peak

References

- ^ "Definition of Himalayas". Oxford Dictionaries Online. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ Himalayan Mountain System. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ Bishop, Barry. "Himalayas (mountains, Asia)". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Shi, Yafeng; Xie, Zizhu; Zheng, Benxing; Li, Qichun (1978). "Distribution, Feature and Variations of Glaciers in China" (PDF). World Glacier Inventory. Riederalp Workshop.

- ^ Henderson-Sellers, Ann; McGuffie, Kendal. The Future of the World's Climate: A Modelling Perspective. pp. 199–201. ISBN 9780123869173.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2010). Monosson, E.; Cleveland, C. (eds.). "Archaea". Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment.

{{cite web}}: Text "location Washington DC" ignored (help) - ^ Miehe, Georg; Miehe, Sabine; Vogel, Jonas; Co, Sonam; Duo, La (May 2007). "Highest Treeline in the Northern Hemisphere Found in Southern Tibet" (PDF). Mountain Research and Development. 27 (2): 169–173. doi:10.1659/mrd.0792.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ "Sunderbans the world's largest delta". gits4u.com.

- ^ Gaillardet, J (2003). "Geochemistry of the Suspended Sediments of Circum-Himalayan Rivers and Weathering Budgets over the Last 50 Myrs" (PDF). Geophysical Research Abstracts. 5 (13617). Retrieved 2006-11-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|quotes=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Vanishing Himalayan Glaciers Threaten a Billion". Planet Ark. June 5, 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ "Glaciers melting at alarming speed". People's Daily Online. July 24, 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ Drews, Carl. "Highest Lake in the World". Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ Devitt, Terry (3 May 2001). "Climate shift linked to rise of Himalayas, Tibetan Plateau". University of Wisconsin–Madison News. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Dallapiccola, Anna (2002). Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend. ISBN 0-500-51088-1.

- ^ Pommaret, Francoise (2006). Bhutan Himlayan Mountains Kingdom (5th ed.). Odyssey Books and Guides. pp. 136–7. ISBN 978-9622178106.

- ^ "Tibetan monks: A controlled life". BBC News. March 20, 2008.

- ^ "Mosques in Lhasa, Tibet". People's Daily Online. October 27, 2005.

Further reading

- Aitken, Bill, Footloose in the Himalaya, Delhi, Permanent Black, 2003. ISBN 81-7824-052-1

- Berreman, Gerald Duane, Hindus of the Himalayas: Ethnography and Change, 2nd rev. ed., Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Bisht, Ramesh Chandra, Encyclopedia of the Himalayas, New Delhi, Mittal Publications, c2008.

- Everest, the IMAX movie (1998). ISBN 0-7888-1493-1

- Fisher, James F., Sherpas: Reflections on Change in Himalayan Nepal, 1990. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 0-520-06941-2

- Gansser, Augusto, Gruschke, Andreas, Olschak, Blanche C., Himalayas. Growing Mountains, Living Myths, Migrating Peoples, New York, Oxford: Facts On File, 1987. ISBN 0-8160-1994-0 and New Delhi: Bookwise, 1987.

- Gupta, Raj Kumar, Bibliography of the Himalayas, Gurgaon, Indian Documentation Service, 1981

- Hunt, John, Ascent of Everest, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1956. ISBN 0-89886-361-9

- Isserman, Maurice and Weaver, Stewart, Fallen Giants: The History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes. Yale University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-300-11501-7

- Ives, Jack D. and Messerli, Bruno, The Himalayan Dilemma: Reconciling Development and Conservation. London / New York, Routledge, 1989. ISBN 0-415-01157-4

- Lall, J.S. (ed.) in association with Moddie, A.D., The Himalaya, Aspects of Change. Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-19-561254-X

- Nandy, S.N., Dhyani, P.P. and Samal, P.K., Resource Information Database of the Indian Himalaya, Almora, GBPIHED, 2006.

- Palin, Michael, Himalaya, London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Illustrated, 2004. ISBN 0-297-84371-0

- Swami Sundaranand, Himalaya: Through the Lens of a Sadhu. Published by Tapovan Kuti Prakashan (August 2001). ISBN 81-901326-0-1

- Swami Tapovan Maharaj, Wanderings in the Himalayas, English Edition, Madras, Chinmaya Publication Trust, 1960. Translated by T.N. Kesava Pillai.

- Tilman, H. W., Mount Everest, 1938, Cambridge University Press, 1948.

- ‘The Mighty Himalaya: A Fragile Heritage,’ National Geographic, 174:624-631 (November 1988).

External links

- The Digital Himalaya research project at Cambridge and Yale

- The making of the Himalaya and major tectonic subdivisions

- Geology of the Himalayan mountains

- Birth of the Himalaya

- Some notes on the formation of the Himalaya

- Pictures from a trek in Annapurna (film by Ori Liber)

- Geology of Nepal Himalaya

- South Asia's Troubled Waters Journalistic project at the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting