Thurgood Marshall: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 207.42.49.202 (talk) to last version by Bradjamesbrown |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{for|people and institutions etc. named after Thurgood Marshall|Thurgood Marshall (disambiguation)}} |

{{for|people and institutions etc. named after Thurgood Marshall|Thurgood Marshall (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{Infobox Judge |

{{Infobox Judge |

||

|name = |

|name = morgan anderson |

||

|image = Thurgood-marshall-2.jpg |

|image = Thurgood-marshall-2.jpg |

||

|imagesize = 220px |

|imagesize = 220px |

||

Revision as of 16:07, 20 April 2010

morgan anderson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court | |

| In office August 30, 1967[1] – October 1, 1991 | |

| Nominated by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Tom C. Clark |

| Succeeded by | Clarence Thomas |

| 32nd United States Solicitor General | |

| In office August 1965 – August 1967 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Erwin N. Griswold |

| Succeeded by | Archibald Cox |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse(s) | Vivian "Busters" Burey, Cecilia Suyat |

| Alma mater | Lincoln University Howard University |

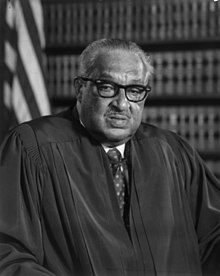

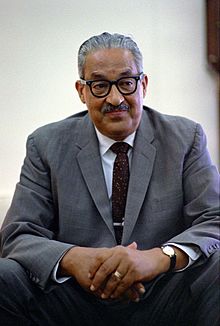

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American jurist and the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States. Before becoming a judge, he was a lawyer who was best remembered for his high success rate in arguing before the Supreme Court and for the victory in Brown v. Board of Education. He was nominated to the court by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967.

Early life

Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland on July 2, 1908, the great-grandson of a slave. His original name was Thoroughgood, but he shortened it to Thurgood in second grade because he disliked spelling it. His father, William Marshall, who was a railroad porter, instilled in him an appreciation for the Constitution of the United States and the rule of law.[2] Additionally, as a child in Baltimore, he was punished for his school misbehavior by being forced to write copies of the Constitution, which he later said piqued his interest in the document.

Marshall was married twice; to Vivian "Buster" Burey from 1929 until her death in February 1955 and to Cecilia Suyat from December 1955 until his own death in 1993. He had two sons from his second marriage;[3] Thurgood Marshall, Jr., who is a former top aide to President Bill Clinton, and John W. Marshall, who is a former United States Marshals Service Director and since 2002 has served as Virginia Secretary of Public Safety under Governors Mark Warner and Tim Kaine.

Education

Marshall graduated from Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore in 1925 and from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1930. Afterward, Marshall wanted to apply to his hometown law school, the University of Maryland School of Law, but the dean told him that he would not be accepted because of the school's segregation policy. Later, as a civil rights litigator, he successfully sued the school for this policy in the case of Murray v. Pearson. As he could not attend the University of Maryland, Marshall sought admission and was accepted at Howard University School of Law.

Law career

Marshall received his law degree from the Howard University School of Law in 1933 where he graduated first in his class.[4] He then set up a private practice in Baltimore. The following year, he began working with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Baltimore. He won his first major civil rights case, Murray v. Pearson, 169 Md. 478 (1936). This involved the first attempt to chip away at the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, a plan created by his co-counsel on the case Charles Hamilton Houston. Marshall represented Donald Gaines Murray, a black Amherst College graduate with excellent credentials who had been denied admission to the University of Maryland Law School because of its separate but equal policies. This policy required black students to accept one of three options, attend: Morgan College, the Princess Anne Academy, or out-of-state black institutions. In 1935, Thurgood Marshall argued the case for Murray, showing that neither of the in-state institutions offered a law school and that such schools were entirely unequal to the University of Maryland. Marshall and Houston expected to lose and intended to appeal to the federal courts. However, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled against the state of Maryland and its Attorney General, who represented the University of Maryland, stating "Compliance with the Constitution cannot be deferred at the will of the state. Whatever system is adopted for legal education now must furnish equality of treatment now". While it was a moral victory, the ruling had no real authority outside the state of Maryland.

Chief Counsel for the NAACP

Marshall won his very first U.S. Supreme Court case, Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940), at the age of 32. That same year, he was appointed Chief Counsel for the NAACP. He argued many other cases before the Supreme Court, most of them successfully, including Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950). His most famous case as a lawyer was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the case in which the Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" public education, as established by Plessy v. Ferguson was not applicable to public education, because it could never be truly equal. In total, Marshall won 29 out of the 32 cases he argued before the Supreme Court.

During the 1950s, Thurgood Marshall developed a friendly relationship with J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1956, for example, he privately praised Hoover's campaign to discredit T.R.M. Howard, a maverick civil rights leader from Mississippi. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to seriously investigate cases such as the 1955 killers of George W. Lee and Emmett Till. Two years earlier Howard had arranged for Marshall to deliver a well-received speech at a rally of his Regional Council of Negro Leadership in Mound Bayou, Mississippi only days before the Brown decision.[5]

President John F. Kennedy appointed Marshall to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. A group of Democratic Party Senators led by Mississippi's James Eastland held up his confirmation, so he served for the first several months under a recess appointment. Marshall remained on that court until 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him Solicitor General.

U.S. Supreme Court

On June 13, 1967, President Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court following the retirement of Justice Tom C. Clark, saying that this was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place." Marshall was confirmed as an Associate Justice by a Senate vote of 69-11 on August 31, 1967.[6] He was the 96th person to hold the position, and the first African-American. President Johnson confidently predicted to one biographer, Doris Kearns Goodwin, that a lot of black baby boys would be named "Thurgood" in honor of this choice (in fact, Kearns's research of birth records in New York and Boston indicates that Johnson's prophecy did not come true).[7]

Marshall served on the Court for the next twenty-four years, compiling a liberal record that included strong support for Constitutional protection of individual rights, especially the rights of criminal suspects against the government. His most frequent ally on the Court (indeed, the pair rarely voted at odds) was Justice William Brennan, who consistently joined him in supporting abortion rights and opposing the death penalty. Brennan and Marshall concluded in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty was, in all circumstances, unconstitutional, and never accepted the legitimacy of Gregg v. Georgia, which ruled four years later that the death penalty was constitutional in some circumstances. Thereafter, Brennan or Marshall dissented from every denial of certiorari in a capital case and from every decision upholding a sentence of death.[citation needed] In 1987, Marshall gave a controversial speech on the occasion of the bicentennial celebrations of the Constitution of the United States.[8] Marshall stated,

"the government they devised was defective from the start, requiring several amendments, a civil war, and major social transformations to attain the system of constitutional government and its respect for the freedoms and individual rights, we hold as fundamental today."

In conclusion Marshall stated

"Some may more quietly commemorate the suffering, struggle, and sacrifice that has triumphed over much of what was wrong with the original document, and observe the anniversary with hopes not realized and promises not fulfilled. I plan to celebrate the bicentennial of the Constitution as a living document, including the Bill of Rights and the other amendments protecting individual freedoms and human rights."[9]

Although he is best remembered for his jurisprudence in the fields of civil rights and criminal procedure, Marshall made significant contributions to other areas of the law as well. In Teamsters v. Terry he held that the Seventh Amendment entitled the plaintiff to a jury trial in a suit against a labor union for breach of duty of fair representation. In TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc. he articulated a formulation for the standard of materiality in United States securities law that is still applied and used today. In Cottage Savings Association v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, he weighed in on the income tax consequences of the Savings and Loan crisis, permitting a savings and loan association to deduct a loss from an exchange of mortgage participation interests. In Personnel Administrator MA v. Feeney, Marshall wrote a dissent saying that a law that gave hiring preference to veterans over non-veterans was unconstitutional because of its inequitable impact on women.

Among his many law clerks were Judge Douglas Ginsburg of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals; Judge Ralph Winter of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit; United States Solicitor General Elena Kagan; well-known law professors Dan Kahan, Cass Sunstein, Eben Moglen, Susan Low Bloch, Martha Minow, Rick Pildes, and Mark Tushnet (and editor of Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions and Reminiscences, cited hereafter); Law Schools Deans Paul Mahoney of University of Virginia School of Law, and Richard Revesz of New York University School of Law. See, List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States.

He retired from the Supreme Court in 1991, and was reportedly unhappy that it would fall to President George H. W. Bush to name his replacement.[10]

Death and legacy

Marshall died of heart failure at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, at 2:58 p.m. on January 24, 1993 at the age of 84. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[11][12][13] His second wife and their two sons survived him.

Marshall left all of his personal papers and notes to the Library of Congress. The Librarian of Congress, James H. Billington, opened Marshall's papers for immediate use by scholars, journalists and the public, insisting that this was Marshall's intent. The Marshall family and several of his close associates disputed this claim.[14] The decision to make the documents public was supported by the American Library Association.[15] A list of the archived manuscripts is available.[16]

There are numerous memorials to Justice Marshall. One is near the Maryland State House. The primary office building for the federal court system, located on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., is named in honor of Justice Marshall and contains a statue of him in the atrium. In 1976, Texas Southern University renamed their law school after the sitting justice.[17] In 1980, the University of Maryland School of Law opened a new library which they named the Thurgood Marshall Law Library.[18] In 2000, the historic Twelfth Street YMCA Building located in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C. was renamed the Thurgood Marshall Center. The major airport serving Baltimore and the Maryland suburbs of Washington, DC, was renamed the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport on October 1, 2005. In 2009 the General Convention of the Episcopal Church USA voted to begin work to establish a liturgical feast day.[19]

Thurgood Marshall Award

The Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico instituted[20] in 1993 the annual Thurgood Marshall Award, given to the top student in civil rights at each of Puerto Rico's four law schools. The awardees are selected by the United States territory's Attorney General and includes a $500 monetary award.

Timeline

- 1908 - Born July 2 at Baltimore, Maryland, United States.

- 1930 - Thurgood graduates with honors from Lincoln University, PA (cum laude).

- 1934 - Thurgood receives law degree from Howard University (magna cum laude); begins private practice in Baltimore, Maryland.

- 1934 - Begins to work for Baltimore branch of NAACP.

- 1935 - Worked with Charles Houston, wins first major civil rights case, Murray v. Pearson.

- 1936 - Becomes assistant special council for NAACP in New York.

- 1940 - Wins Chambers v. Florida, the first of twenty-nine Supreme Court victories.

- 1943 - Won case for integration of schools in Hillburn, New York.

- 1944 - Successfully argues Smith v. Allwright, overthrowing the South's "white primary".

- 1946 - Thurgood Marshall received a medal from the NAACP.

- 1948 - Wins Shelley v. Kraemer, in which Supreme Court strikes down legality of racially restrictive covenants.

- 1950 - Wins Supreme Court victories in two graduate-school integration cases, Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents.

- 1951 - Visits South Korea and Japan to investigate charges of racism in U.S. armed forces. He reported that the general practice was one of "rigid segregation."

- 1954 - Wins Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, landmark case that demolishes legal basis for segregation in America.

- 1956 - Wins Browder v. Gayle, ending the practice of segregation on buses and ending the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

- 1957 - Founds and becomes the first president-director counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., a nonprofit law firm separate and independent of the NAACP

- 1961 - Defends civil rights demonstrators, winning Supreme Court victory in Garner v. Louisiana; nominated to Second Circuit Court of Appeals by President J.F. Kennedy.

- 1961 - Appointed circuit judge, makes 112 rulings, none of them reversed on certiorari by Supreme Court (1961–1965).

- 1965 - Appointed United States Solicitor General by President Lyndon B. Johnson; wins 14 of the 19 cases he argues for the government (1965–1967).

- 1967 - Becomes first African American elevated to U.S. Supreme Court (1967–1991).

- 1991 - Retires from the Supreme Court.

- 1992 - Receives the Liberty Medal recognizing Marshall's long history of protecting individual rights under the Constitution.

- 1993 - Dies at age 84 in Bethesda, Maryland, near Washington, D.C.

- 1993 - Receives Presidential Medal of Freedom, posthumously, from President Bill Clinton.

For more, see Bradley C. S. Watson, "The Jurisprudence of William Joseph Brennan, Jr., and Thurgood Marshall" in Frost, Bryan-Paul and Jeffrey Sikkenga. eds. History of American Political Thought (Lexington: Lexington Books, 2003). ISBN 0739106236; ISBN 978-0739106235; ISBN 9780393928860.

Books authored

- Marshall, Thurgood; Tushnet, Mark V. (Editor); and Kennedy, Randall (Forward by). (2001). Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions and Reminiscences. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, Incorporated -- Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 9781556523861.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Bland, Randall W. "Private Pressure on Public Law: The Legal Career of Justice Thurgood Marshall 1934-1991". New York: University Press of America, 1993.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1568021267.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791013774; ISBN 978-0791013779.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195058356; ISBN 9780195058352.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Hodges, Ruth A., Reference Librarian. Justice Thurgood Marshall: A Selected Bibliography, (Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Washington, DC, February, 1993).

- James Jr, Rawn (2010). Root and Branch: Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, and the Struggle to End Segregation. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|publisher=and|title= - Marshall, Thurgood. "Mr. Justice Murphy and Civil Rights." 48 Michigan Law Review 745 (1950).

- Martin, Fenton S. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0871875543.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Tushnet, Mark V. Making Civil Rights Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1936-1961. London: Oxford University Press, 1994. 399pp. ISBN 9780195104684;

- Tushnet, Mark V. Making Constitutional Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1961-1991. New York: Oxford University Press. 1997. ISBN 0195093143 pp., 256.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0815311761; ISBN 978-0815311768.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Vile, John R., ed. (2003), Great American Judges: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1, Santa Barbara: ABC–CLIO, ISBN 978-1576079898.

- White, G. Edward (2007), The American Judicial Tradition: Profiles of Leading American Judges (3rd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195139624.

- Williams, Juan, Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary (New York: New York Times, 1998). Promotional site for book ISBN 0812932994; ISBN 978-0812932997.

- Woodward, Robert (1979). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York. ISBN 9780380521838; ISBN 0380521830. ISBN 9780671241100; ISBN 0671241109; ISBN 0743274024; ISBN 9780743274029..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Notes

- ^ "Federal Judicial Center: Thurgood Marshall". 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ A Thurgood Marshall time line: provided by A Deeper Shade of Black

- ^ American Public Radio: Cissy Marshall

- ^ Bland;6, 1933

- ^ David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, Black Maverick: T.R.M. Howard's Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 132-35, 157-58.

- ^ Graham, Fred P. (August 31, 1967) Senate Confirms Marshall As the First Negro Justice; 10 Southerners Oppose High Court Nominee in 69-to-11 Vote. New York Times.

- ^ According to the Social Security Administration Popular baby name database, Thurgood has never been in the top 1000 of male baby names.

- ^ Tinsley E. Yarbrough (2000). The Rehnquist Court and the Constitution. Oxford University Press US. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ^ ThurgoodMarshall.com, Speeches. Constitutional Speech, May 6, 1987. Retrieved on April 7, 2009.

- ^ Lee Epstein, Jeffrey Allan Segal (2005). Advice and consent: the politics of judicial appointments. Oxford University Press US. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Thurgood Marshall Memorial at Find a Grave.

- ^ Christensen, George A., Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited, Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17 - 41 (Feb 19, 2008), University of Alabama.

- ^ See generally, Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- ^ Lewis, Neil A. (May 26, 1993). "Chief Justice Assails Library On Release of Marshall Papers". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ^ American Library Association statement of support.

- ^ Cartledge, Connie L., assisted by Allyson H. Jackson, Susie H. Moody, Andrew M. Passett, and Robert A. Vietrogoski, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Thurgood Marshall: A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress (2001)

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ Legislative Service Bureau, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Burger Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

External links

- Ariens, Michael, Thurgood Marshall.

- Fox, John, Expanding Civil Rights, Biographies of the Robes, Thurgood Marshall. Public Broadcasting Service.

- Miscellaneous biographies at Answers.com.

- Oyez, official Supreme Court media, Thurgood Marshall.

- Supreme Court Historical Society Thurgood Marshall.

- Thurgood Marshall at Find a Grave

- REMARKS BY THE PRESIDENT IN CEREMONY HONORING MEDAL OF FREEDOM RECIPIENTS - November 30, 1993

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1967-1969 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1969 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1970-1971 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1972-1975 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1975-1981 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1981-1986 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1986-1987 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1988-1990 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1990-1991 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- United States Supreme Court justices

- United States federal judges appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson

- Solicitors General of the United States

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- United States court of appeals judges appointed by John F. Kennedy

- African American politicians

- African American lawyers

- African American judges

- African Americans' rights activists

- Maryland lawyers

- Howard University alumni

- Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) alumni

- American Episcopalians

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- People from Baltimore, Maryland

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- 1908 births

- 1993 deaths

- Cardiovascular disease deaths in Maryland

- American civil rights lawyers

- Lyndon B. Johnson Administration personnel

- History of African-American civil rights

- Spingarn Medal winners