Moby

Moby | |

|---|---|

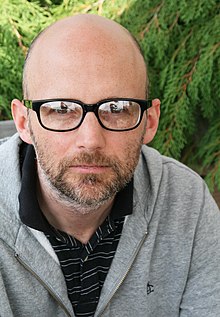

Moby in 2009 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Richard Melville Hall |

| Born | September 11, 1965 Harlem, New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1978–present |

| Labels | |

| Website | moby |

Richard Melville Hall (born September 11, 1965), better known as Moby, is an American musician, songwriter, singer, producer, and animal rights activist. He has sold 20 million records worldwide. AllMusic considers him to be "among the most important dance music figures of the early 1990s, helping bring dance music to a mainstream audience both in the United Kingdom and the United States".[1]

After taking up guitar and piano at age nine, he played in several underground punk rock bands through the 1980s before turning to electronic dance music. In 1989, he moved to New York City and became a prolific figure as a DJ, producer, and remixer. His 1991 single "Go" was his mainstream breakthrough, reaching No. 10 in the United Kingdom. Between 1992 and 1997 he scored eight top 10 hits on the Billboard Dance Club Songs chart including "Move (You Make Me Feel So Good)", "Feeling So Real", and "James Bond Theme (Moby Re-Version)". Through the decade he also produced music under various pseudonyms, released the critically acclaimed Everything Is Wrong (1995), and composed music for films. His punk-oriented album Animal Rights (1996) alienated much of his fan base.

Moby found commercial and critical success with his fifth album Play (1999) which, after receiving little recognition, became an unexpected global hit in 2000 after each track was licensed to films, television shows, and commercials. It remains his highest selling album with 12 million copies sold.[2] Its seventh single, "South Side", featuring Gwen Stefani, remains his only one to appear on the US Billboard Hot 100, reaching No. 14. Moby followed Play with albums of varied styles including electronic, dance, rock, and downtempo music, starting with 18 (2002), Hotel (2005), and Last Night (2008). His later albums saw him explore ambient music, including the almost four-hour release Long Ambients 1: Calm. Sleep. (2016). Moby has not toured since 2014 but continues to record and release albums; his most recent is Long Ambients 2 (2019). Moby has co-written, produced, or remixed music for various artists.

In addition to his music career, Moby is known for his veganism and support for animal welfare and humanitarian aid. He is the owner of Little Pine, a vegan restaurant in Los Angeles, and organized the vegan music and food festival Circle V. He is the author of four books, including a collection of his photography and two memoirs: Porcelain: A Memoir (2016) and Then It Fell Apart (2019).

Early life

Richard Melville Hall was born September 11, 1965, in the neighborhood of Harlem in Manhattan, New York City. He is the only child of Elizabeth McBride (née Warner), a medical secretary, and James Frederick Hall, a chemistry professor, who died in a car crash while drunk when Moby was two.[3][4][5][6] His father gave him the nickname Moby three days after his birth as his parents considered the name Richard too large for a newborn baby. The name was also a reference to the family's ancestry; Hall says he is the great-great-great nephew of Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick.[7][8]

Moby was raised by his mother, first in San Francisco from 1969 for a short period. He recalled being sexually abused by a staff member at his daycare during this time.[9] This was followed by a move to Darien, Connecticut,[10][11] living in a squat with "three or four other drug-addicted hippies, with bands playing in the basement."[12] The two moved to Stratford, Connecticut for a brief time.[13] His mother struggled to support her son, often relying on food stamps and government welfare.[3] They occasionally stayed with Moby's grandparents in Darien, but the affluence of the suburb made him feel poor and ashamed.[12] Shortly before his mother's death, Moby learned from her that he has a half brother.[12] His first job was a caddy at a golf course.[14]

Moby took up music at the age of nine.[15] He started on classical guitar and received piano lessons from his mother[7] before studying jazz, music theory, and percussion. In 1983, he became the guitarist in a hardcore punk band, the Vatican Commandos, playing on their debut EP Hit Squad for God.[16] Around this time he was the lead vocalist for Flipper for two days; Moby played bass for their reunion shows in the 2000s.[17] Moby formed a post punk group named AWOL around the time of his eighteenth birthday. He is credited on their only release, a self-titled EP, as Moby Hall.[18]

In 1983, Moby graduated from Darien High School[19] and started a philosophy degree at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut. Around this time he had found the instruments he had learned "sonically limiting" and moved to electronic music.[20] He spun records at the campus radio station WHUS which led to DJ work in local clubs and bars.[7] Moby grew increasingly unhappy at university, however, and transferred to State University of New York at Purchase, studying philosophy and photography, to try and renew his interest in studying. He dropped out in April 1984 to pursue DJ'ing and music full-time, which started his interest in electronic dance music.[3][21][22] For two years he lived in Greenwich, Connecticut where he DJ'd at The Cafe, an under-21 nightclub at the back of a church.[23][24] In 1987, he started to send demos of his music to record labels in New York City; he failed to receive an offer which led to a two-year period of "very fruitless labor".[24] Around 1988, Moby moved into a semi-abandoned factory in Stamford, Connecticut that had no bathroom or running water, but the free electricity supply allowed him to work on his music,[22] using a 4-track recorder, synthesizer, and drum machine.[25]

Career

1989–1993: Signing with Instinct, "Go", and breakthrough

In 1989, Moby relocated to New York City with his close friend, artist Damian Loeb.[10][18] In addition to performing DJ sets in local bars and clubs, he played guitar in alternative rock group Ultra Vivid Scene and appeared in the video for their 1989 single "Mercy Seat".[26][27] In 1990, Moby joined Shopwell and played on their album Peanuts.[28][29] Moby's first live electronic music gig followed in the summer of 1990 at Club MK; he wore a suit for the show.[24][30] His future manager Eric Härle, who was in attendance, recalled Moby's set: "The music was amazing, but the show was riddled with technical mishaps. It left me very intrigued and impressed in a strange way."[31]

By mid-1990, Moby had signed a deal as the sole artist of Instinct Records, an independent New York City-based dance label then still in its infancy. The three-man operation saw Moby answer incoming calls and make records in a studio he set up in the owner's lounge.[32] To appear that Instinct had more artists, Moby's early singles were put out under several names such as Voodoo Child, Barracuda, Brainstorm, and UHF.[24] The first, "Time's Up" as The Brotherhood, was co-written by Moby and vocalist Jimmy Mack.[33][34] This was followed by "Mobility", his first single released as Moby, in November 1990 which sold an initial 2,000 copies.[30] He then scored a breakthrough hit with a remix of "Go", originally a B-side to "Mobility" with an added sample of "Laura Palmer's Theme" by Angelo Badalamenti from the television series Twin Peaks. Released in March 1991, it peaked at No. 10 in the UK in October and earned him national exposure there with an appearance on Top of the Pops.[31] Instinct capitalised on Moby's success with the late 1991 compilation Instinct Dance featuring tracks by Moby and his pseudonyms. The following year, Moby revealed that "Go" had earned him just $2,000 in royalties.[34]

The success of "Go" led to increased demand for Moby to produce more music and to remix other artists' songs. He often arranged for the artist and himself to trade remixes as opposed to being paid for his work, which was the case for his mixes for Billy Corgan and Soundgarden.[35] The increased mainstream exposure led Moby to request a release from his contract with Instinct for a bigger label. Instinct refused, so Moby retaliated by holding out on new material. However, Instinct continued to put out records, mostly from demos, without his consent having previously copied many of his tapes and had the master rights.[7][32] This was the case for Moby's debut album, Moby, released in July 1992 and formed mostly of previously unreleased demos that Moby considered old and unrepresentative of the musical direction he had taken since. Nonetheless, he claimed Instinct had insisted and had the legal right to put it out.[36][37] It was re-titled The Story So Far and presented with a different track listing for its UK release. Four singles were released: "Go", "Drop a Beat", "Next Is the E", and a double A-side of "I Feel It" with "Thousand". The latter was recognised by Guinness World Records as the fastest tempo in a recorded song at 1,015 beats-per-minute.[13][38]

In 1992, Moby completed his first US tour as the opening act for The Shamen.[24][39] In mid-1992, Moby estimated that he had earned between $8,000 to $11,000 a year for the past six years.[34] At the 1992 Mixmag awards, he smashed his keyboard after his set.[30] After his second nationwide tour, this time with The Prodigy and Richie Hawtin, in early 1993,[24] a second compilation of Moby's work for Instinct followed named Early Underground. His second and final album on Instinct, Ambient, was released in August 1993. It is a collection of mostly ambient techno instrumentals of a more experimental style. By this time Instinct had agreed to release Moby who then took legal action, claiming that the label demanded "a ridiculous amount of money" that he did not have to leave. He also expressed disagreements over the way Instinct had packaged and handled his music.[39] Moby was eventually released after he paid the label $10,000.[20]

1993–1998: Signing with Elektra, Everything Is Wrong, and Animal Rights

In 1993, Moby signed with Elektra Records which lasted for five years. He secured a deal with Mute Records, a British label, to handle his European distribution.[18][40] Moby's output for Elektra/Mute began with Move, a four-track EP released in August 1993. He attempted to make it in a professional studio, but he disliked the results and re-recorded it at home. The song "All That I Need Is to Be Loved (MV)" is his first song to feature his own vocals.[39] The first single, "Move (You Make Me Feel So Good)", reached No. 1 on the US Billboard Hot Dance Music/Club Play chart and No. 21 in the UK.[41] In 1993, Moby toured as the headlining act with Orbital and Aphex Twin. A rift developed between Aphex Twin and himself, partly due to Moby's refusal to tolerate their cigarette smoke, so he travelled to each gig by plane, leaving the rest on the tour bus.[30] In 1994, Moby put out Demons/Horses, an electronic album of two 20-minute tracks under the name Voodoo Child.[42]

Moby's contract with Elektra allowed the opportunity to make his third full-length album, which was underway in 1994. He chose to include a variety of musical styles on the album that he either liked or had been influenced by, including electronic dance, ambient, rock, and industrial music. Everything Is Wrong was released in March 1995 to critical praise; Spin magazine named it Album of the Year and some commentators considered it to be an album ahead of its time as it failed to crack the Billboard 200 or have an impact on the dance charts.[43][44] In the UK, the album reached No. 25 and the singles "Hymn" and "Feeling So Real" went to Nos. 31 and 30, respectively. Elektra took advantage of its diverse sound by distributing tracks of the same style to corresponding radio stations nationwide.[7] Early copies put out in the UK and Germany included a bonus CD of ambient music entitled Underwater. Moby toured the album with some headline spots on the second stage at the 1995 Lollapalooza festival.[44] He followed it with a double remix album, Everything Is Wrong—Mixed and Remixed.

The success of Everything Is Wrong had Moby reach a new peak in critical acclaim. The Los Angeles Times thought the 29-year-old Moby was "poised for greatness [...] to make that big crossover" from a respected underground artist to a mainstream dance and rock musician.[44] Billboard declared him "King of techno" and Spin named him "the closest techno comes to a complete artist."[45] In 1995, Moby was approached by Courtney Love to produce the next Hole album, but he declined.[30] He directed the music video for "Young Man's Stride" by Mercury Rev.[46] In 1995 and 1996, Moby put out a number of "self-indulgent dance" singles under the pseudonyms Lopez and DJ Cake on Trophy Records, his own Mute imprint, so he could release material that he was interested in without concern for its commercial impact.[21] In 1996, Moby contributed "Republican Party" to the AIDS benefit album Offbeat: A Red Hot Soundtrip produced by the Red Hot Organization and released his second Voodoo Child album, The End of Everything.[47]

While touring Everything Is Wrong, Moby had grown bored with the electronic scene and felt the press had failed to understand his records and take them seriously. This marked a major stylistic change for his next album, Animal Rights, combining guitar-driven rock songs with Moby on lead vocals and softer ambient tracks.[48][49] Upon completing the album Moby said that it was "weird, long, self-indulgent and difficult".[31][47] Its lead single is a cover version of "That's When I Reach for My Revolver" by post-punk group Mission of Burma. Animal Rights was released in September 1996 in the UK, where it peaked at No. 38, and in February 1997 in the US. It was poorly received by his dance fan base who felt Moby had abandoned them, creating doubts as to what kind of artist Moby really was. Moby pointed out that he had not abandoned his electronic music completely and had worked on dance and house mixes and film scores while making Animal Rights.[35][50]

After Animal Rights, Moby's manager recalled: "We found ourselves struggling for even the slightest bit of recognition. He became a has-been in the eyes of a lot of people in the industry".[31] Despite the hit in sales and critical response, Moby promoted the album with a European tour with Red Hot Chili Peppers and Soundgarden, and headlined the Big Top tour with other dance and electronic DJs.[49] He returned to the genre after liking the house music that a friend and DJ had played at a party.[50] In October 1997, Moby displayed his range of music styles with the release of I Like to Score, a compilation of his film soundtrack work with some re-recorded tracks.[49][51] Among them are updated version of the "James Bond Theme" used for Tomorrow Never Dies, music used in Scream, and a cover of "New Dawn Fades" by Joy Division, an instrumental version of which appeared in Heat.[51][52] Late 1997 saw Moby start his first US tour in two years.[53]

In 1998, Elektra granted Moby's request to be released from his deal on the condition that he paid to leave, which amounted to "quite a lot". He felt Elektra did little to capitalise on the critical success of Everything Is Wrong, and that it was only interested in radio friendly hits.[54] Left without an American distributor, his only deal remained with the UK-based Mute Records.[18][55] Moby considered himself an artist that did not belong to a major label as his music did not fit with the genres that they promoted.[40]

1999–2004: Play, worldwide success, and 18

Moby's fifth album, Play, was released by Mute and V2 Records, founded by Richard Branson three years prior, in May 1999. The project originated when a music journalist introduced Moby to the field recordings of Alan Lomax from the compilation album Sounds of the South: A Musical Journey From the Georgia Sea Islands to the Mississippi Delta. Moby took an interest in the songs and formed samples from various tracks which he used to base new tracks of his own.[56] Upon release in May 1999, Play had moderate sales but eventually sold over 10 million copies worldwide.[57] Moby toured worldwide in support of the album which lasted 22 months.[58] Every track on Play was licensed to various films, advertisements, and television shows, as well as independent films and non-profit groups.[59] The move was criticised and led to some to consider that Moby had become a sellout, but he later maintained that the licenses were granted mostly to independent films and non-profit projects, and agreed to them due to the difficulty of getting his music heard on the radio and television in the past.[14] In 2007, The Washington Post published an article about a mathematical equation dubbed the "Moby quotient" that determined to what degree had a musical artist sold out. It was named in reference to his decision to license music from Play.[14][60]

In 2000, Moby contributed "Flower" to Gone in 60 Seconds.[61] He co-wrote "Is It Any Wonder" with Sophie Ellis-Bextor for her debut solo album, Read My Lips. Moby: Play - The DVD, released in 2001, features the music videos produced for the album, live performances, and other bonus features. It was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video.[62] In 2001, Moby founded the Area:One Festival which toured the US and Canada across 17 shows that summer with a range of artists. The set included Outkast, New Order, Incubus, Nelly Furtado, and Paul Oakenfold, with Moby headlining.

Moby started on the follow-up to Play in late 2000.[18] Prior to working on tracks for 18, he got friends to search for records with vocals that he could use and make samples from and went on to write over 140 songs for the album.[63] At the same time, Moby familiarised himself with the ProTools software and made 18 with it.[18] Released in May 2002, 18 went to No. 1 in the UK and eleven other countries, and No. 4 in the US. It went on to sell over four million copies worldwide.[64] Moby toured extensively for both Play and 18, playing over 500 shows in the next four years.[65] The tour included the Area2 Festival in the summer of 2002, featuring a line-up of Moby, David Bowie, Blue Man Group, Busta Rhymes, and Carl Cox.[66] In December 2002, during a tour stop at Paradise Rock Club in Boston, Moby was punched in the face and sprayed with mace by two or three assailants while signing autographs outside the venue. The incident left him with multiple bruises and cuts.[67]

In February 2002, Moby performed at the closing ceremony of the Winter Olympics.[30] That month he hosted the half-hour MTV series Señor Moby's House of Music, presenting a selection of electronic and dance music videos.[68] His song "Extreme Ways" was used in all five of the Bourne films, from 2002 to 2012.[69] Moby said that after it was used for the first, the producers originally sought a different artist for the second but they had too little time to secure someone, leading them to pick "Extreme Ways" for the entire series.[70] In 2002, rapper Eminem mocked Moby in his song "Without Me" and its music video, dressing up like him and calling him an "old baldheaded fag" and his techno music outdated. Eminem had also shot a mock figure of Moby on stage. Moby put the attack down to Eminem having "this unrequited crush on me."[71]

In 2003, Moby headlined the Glastonbury Festival on the final day.[72] He co-wrote and produced "Early Mornin'" for Britney Spears' album In the Zone released that year. Moby returned to his dance and rave roots with the release of Baby Monkey, the third album under his Voodoo Child moniker, in 2004.[73] Later that year, he collaborated with Public Enemy on "Make Love Fuck War", a protest song against the Iraq War.[74]

2004–2010: Hotel, Last Night, and Wait for Me

Moby's seventh album, Hotel, was released in March 2005. The album contains little use of samples, which Moby reasoned to using different audio recording software which had a sampling function that was too difficult to learn, "so it was me just being lazy". He nonetheless said that Hotel is a more satisfying album as a result.[75] The instruments were recorded live by Moby except for the drums, for which he enlisted his longtime live drummer Scott Frassetto. The album features vocals from six other performers, including Laura Dawn and Shayna Steele.[76] In 2013, Moby looked back on the album as his least favourite of his career, pointing out that it was the only one not recorded at his home studio.[17] The singles "Lift Me Up" and "Slipping Away" became top-10 hits across Europe.[77] Early copies of the album included a bonus CD of remixes and ambient music entitled Hotel: Ambient that was released on its own in 2014.[78]

In 2006, he accepted an offer to score the soundtrack for Richard Kelly's 2007 movie Southland Tales, because he was a fan of Kelly's previous film, Donnie Darko.[79] In 2007, Moby also started a rock band, The Little Death with his friends Laura Dawn, Daron Murphy, and Aaron A. Brooks.[80] Following the dissolution of V2 Records in 2007, Moby signed a new deal with Mute Records to handle his American distribution.[81] In 2007 Moby produced and performed on a remake of "The Bulrushes" by The Bongos that appeared on the special anniversary edition of the group's debut album Drums Along the Hudson, on Cooking Vinyl Records. From 2007 to 2008 he ran a series of New York club events titled "Degenerates".[82][83]

In 2008, Moby released Last Night, an electronic dance album inspired by a night out in his New York City neighborhood. The album was recorded in Moby's home studio and features various guest vocalists, including Wendy Starland, MC Grandmaster Caz, Sylvia of Kudu, MC Aynzli, and the Nigerian 419 Squad.[84] The singles from Last Night include "Alice" and "Disco Lies".

Moby wished for the follow-up to Last Night to be emotional, personal, and melodic.[85] He felt creatively inspired by a David Lynch speech at the BAFTA Award ceremony in the UK which prompted him to write new material that he liked with little regard to its mainstream commercial success.[86] He decided against recording in a professional studio as he wanted to record the entire album at home, and chose to have the album mixed using analogue equipment. Wait for Me was released on June 30, 2009.[86][87][88] Moby and Lynch discussed the recording process of Wait for Me on Lynch's online channel, David Lynch Foundation Television Beta.[89] The video to the first single, "Shot in the Back of the Head", offered as a free download, was directed by Lynch.[86]

Moby held a user-generated content competition to have fans create a video for "Wait for Me", the last single from the album, which was to be used as the official video. The winning entry was written and directed by Nimrod Shapira of Israel, and portrays the story of a girl who decides to invite Moby into her life. She attempts to do so by using a book called How to Summon Moby, A Guide for Dummies, putting herself through bizarre and comical steps, each is a tribute to a different Moby video.[90] The single was released in May 2010.[91]

The Wait for Me tour featured a full band.[92] Moby raised over $75,000 from three shows in California to help those affected by domestic violence[93] after funding for the state's domestic violence program had been cut. The tour also saw Moby headline the Falls Festival in Australia[94] and various Sunset Sounds festivals.[95] An ambient version Wait for Me was released in late 2009 as Wait for Me: Ambient, which Moby did not produce.[96]

In 2010, Moby enlisted vocalist Phil Costello as a songwriting partner for a new heavy metal band, Diamondsnake. After writing 13 songs, they recruited guitarist Dave Hill and a drummer named Tomato to complete the line-up. They recorded their self-titled debut album in one day and released it for free on their website. It was promoted with a series of gigs in New York City and Los Angeles.[97] Moby contributed four songs to the soundtrack of The Next Three Days, including the single "Mistake".

2010–2015: Destroyed and Innocents

In January 2010, Moby announced that he had started work on a new album.[98] He later summarised its style as: "Broken down melodic electronic music for empty cities at 2 a.m."[99] The album was promoted with an EP containing three tracks from the album, given free to those who had signed up to Moby's mailing list, entitled Be the One, in February 2011.[99][100] The album, Destroyed, was released in May 2011.[100][99] A same-titled book of Moby's photography was released around the time of the album.[99] Moby took to an online poll to decide the next single from Destroyed; the fans picked "Lie Down in Darkness".[101] This was followed by "After" and "The Right Thing", both influenced as to what fans had picked.[102] A limited edition remixed version of Destroyed was released in 2012 as Destroyed Remixed and includes new remixes by David Lynch, Holy Ghost! and System Divine, and a new 30-minute ambient track named "All Sides Gone".

Moby toured worldwide through 2013, completing acoustic and DJ sets at various concerts and festivals.[103][104][105] His DJ set at Coachella was produced in collaboration with NASA with various images from space projected onto screens during the performance.[106] On Record Store Day in 2013, Moby released a 7-inch record, The Lonely Night, featuring Screaming Trees vocalist Mark Lanegan.[107] The track was subsequently released as a download with remixes by Moby, Photek, Gregor Tresher, and Freescha.[108]

In October 2013, Moby released Innocents. He had worked on the album for the previous 18 months and hired Spike Stent to produce it. Moby used several guest vocalists on the album, and picked Neil Young and "Broken English" by Marianne Faithfull as the biggest influences to the musical style on the album.[109] As with Destroyed, the photography used for the artwork were all shot by Moby. The first single from the album was "A Case for Shame",[110] followed by "The Perfect Life", which featured Wayne Coyne. A casting call for its video asked "for obese Speedo-sporting bikers, nude rollerskating ghosts, and an S&M gimp proficient in rhythmic gymnastics".[111] Moby promoted the album with three shows at the Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles, following his decision to undergo little touring from 2014.[109] He wrote: "Pretty much all I want to do in life is stay home and make music. So, thus: a 3 date world tour."[112]

Six of Moby's songs are feature in Charlie Countryman (2013).[113] His music set the tone to Cathedrals of Culture (2014), a 3D documentary film about the soul of buildings, directed by Wim Wenders.[114] In December 2014, Moby performed three shows of ambient music at the Masonic Lodge in Hollywood Forever Cemetery to support the release of Hotel: Ambient. The performances were accompanied by visuals created by himself and with David Lynch.[78]

2016–present: These Systems Are Failing and recent albums

After Innocents, Moby proceeded to make a new wave dance album with a choir, but realised the difficulty in recording a full choir in his home studio and resorted to multi-tracking vocals performed by himself and guests. He then decided against the new wave album and opted for one made by himself and seven guest vocalists he named the Void Pacific Choir.[64] These Systems Are Failing was announced in September 2016 and coincided with the first single release, "Are You Lost In The World Like Me?". Its video, by animator Steve Cutts, addresses smartphone addiction which won a Webby Award.[115][116][117][118] These Systems Are Failing was released on October 14, 2016.[119] Moby's sole live performance of 2016 was at Circle V, a vegan food and music festival that he founded that took place on October 23 at the Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles.[120] A second album with the Void Pacific Choir name followed in June 2017, entitled More Fast Songs About the Apocalypse, influenced by the results of the 2016 United States presidential election. Released for free online, it was marketed from a spoof website using elected President Donald Trump's alleged PR alter-ego, John Miller.[121]

Moby announced his fifteenth studio album, Everything Was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt, in December 2017. The announcement coincided with the release of the first single, "Like a Motherless Child". In contrast to the politically inspired and punk nature of the two Void Pacific Choir records, the album explores themes of spirituality, individuality, and humanity.[122][123][124] The album was released on March 2, 2018.[122] The second single, "Mere Anarchy", was described by Moby as "post apocalypse, people are gone, and my friend Julie and I are time traveling aliens visiting the empty Earth."[125] "This Wild Darkness" was the third single, released in February 2018.[126] Moby described the song as "an existential dialog between me and the gospel choir: me talking about my confusion, the choir answering with longing and hope."[126] Moby promoted the album with three live shows in March 2018 with a full band, one at The Echo in Los Angeles and two at Rough Trade in New York City.[127] All profits from the album and gigs were donated to animal rights organizations.[128]

In 2018, Moby was a guest performer on "A$AP Forever" by American rapper A$AP Rocky which samples "Porcelain". This resulted in Moby's second ever appearance on the US Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, having previously charted for "Southside", 17 years prior.[129] Moby contributed several songs to the comedy Half Magic (2018) directed by Heather Graham.[130]

In March 2019, Moby released a follow-up to his first long ambient album, Long Ambients 2.

Collaborations

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

Moby has collaborated live with many of his heroes while on tour or at fundraisers. He has performed "Walk on the Wild Side" with Lou Reed, "Me and Bobby McGee" with Kris Kristofferson, "Heroes" and "Cactus" with David Bowie, "Helpless" with Bono and Michael Stipe, "New Dawn Fades" with New Order, "Make Love, Fuck War" with Public Enemy, "Whole Lotta Love" with Slash, and "That's When I Reach For My Revolver" with Mission of Burma.

He has performed two duets with the French singer Mylène Farmer ("Slipping Away (Crier la vie)" in 2006 and "Looking for My Name" in 2008) and produced seven songs on her eighth album, Bleu Noir, released on December 6, 2010.[131]

In 2006, Moby released a Spanish version of his song "Slipping Away" called "Escapar", in which the Spanish group Amaral took part.

In 2012, he collaborated with Spain-based group Dubsidia, making dubstep and electro house.

In 2013, Moby was responsible for the soundtrack of the documentary The Crash Reel, who tells the story of snowboarder Kevin Pearce.

On October 16, 2015, Jean Michel Jarre released his compilation album Electronica 1: The Time Machine, which included the track "Suns have gone" co-produced by Jarre and Moby.[132]

On September 24, 2016, Moby announced the release of an album titled These Systems Are Failing, released under the name Moby & Void Pacific Choir. The followed the release of two singles from Moby & The Void Pacific Choir in 2015, "Almost Loved" & "The Light Is Clear In My Eyes".[133]

He appeared in "Part 10" of TV series Twin Peaks accompanying American singer Rebekah Del Rio performing "No Stars".

TV work

Starz aired a special episode of Blunt Talk, the Patrick Stewart comedy which involved Moby. He had been friends with Jonathan Ames for a long time, and "when we both lived in NY we did a lot of really strange, cabaret, vaudeville type shows together, and we just sort of stayed friends over the years. I guess when he and the other writers were writing Blunt Talk one of them thought it would be funny to include me as Patrick Stewart’s character's ex-wife’s current boyfriend."[134]

Moby was one of the first musicians to have an episode on Netflix's new music documentary series titled Once In a Lifetime Sessions; where he records, discusses, and performs his music.[135]

Business ventures

Starting in around 2001, Moby launched a series of co-owned business ventures, with the two most prominent being the Little Idiot Collective—a New York City, U.S. bricks-and-mortar clothing store, comics store, and animation studio[136] that sold the work of an "illustrators collective". In May 2002, Moby launched a small raw and vegan restaurant and tea shop called TeaNY in New York City with his then girlfriend Kelly Tisdale.[6][137] In 2006, Moby said he had removed himself from any previous business projects.[138]

In November 2015, Moby opened the Vegan restaurant Little Pine in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, California.[139] The restaurant serves organic, vegan, Mediterranean-inspired dishes and has a retail section with art and books, curated by Moby himself.[140] All profits are donated to animal welfare organizations; in May 2016, Moby estimated the year's donations at $250,000.[141] In December 2019, Moby launched the Little Pine lifestyle range of products and merchandise, with all profits donated to six charities.[142]

On August 23, 2016, Moby announced the inaugural Circle V Festival along with the official video for 'Don't Leave Me' by Moby & The Void Pacific Choir.[143] The event took place at LA's Fonda Theatre and featured Blaqk Audio & Cold Cave on the bill amongst others in the evening and talks and vegan food stalls in the afternoon. Moby described Circle V as "the coming together of my life’s work, animal rights and music. I couldn’t be more excited about this event and am so proud to be head-lining." [144]

The second Circle V event took place on November 18 this time at The Regent Theatre in Los Angeles. Moby headlined the event for the second year with artists Waka Flocka Flame, Dreamcar and Raury featuring on the bill.[145]

Personal life

Moby has posted updates on his blog via his official website since September 2000.[146]

In March 2008, after Gary Gygax's death, Moby was one of several celebrities identifying themselves as former Dungeons & Dragons players.[147][148]

Moby lived in New York City for 21 years. From 1996 to 2010, he lived in a studio apartment on Mott Street where he also recorded his albums.[149] He then relocated to a castle in the Hollywood Hills area of Los Angeles named Wolf's Lair, first owned by Milton R. Wolf, for almost $4 million and spent an additional $2 million to restore it. He also owns an apartment in Little Italy, Manhattan.[10] In 2014, Moby sold the property and downsized to a smaller home in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles.[150]

In June 2013, Moby and numerous other celebrities appeared in a video showing support for Chelsea Manning.[151][152] In January 2018, he stated that he was approached by friends in the CIA and told to post and spread content on the Trump–Russian collusion allegations through social media.[153][154]

Moby identifies himself as heterosexual and cisgender and had felt "disappointed" to be straight.[12] He dated Christina Ricci.[3] In 2019, he claimed in a book to have had a brief relationship with actress Natalie Portman, though she has denied this and pointed out that her age in the book is incorrect (in reality, she was just 18 at the time).[155] He does date, but has stated that that he feels more comfortable alone than in a relationship.[12] In 2016, he was in an eight-month relationship, his first in ten years. He has no children.[4][6]

Moby practices meditation and has explored different types, including transcendental, Mettā, and Vipassanā.[156]

Veganism and animal rights

In 1984, Moby was inspired to become a vegetarian by a cat named Tucker that he had found at a dump in Darien, Connecticut. "My mom and I, with the help of George the dachshund, took care of Tucker and he grew up to be the happiest, healthiest cat I'd ever known". In November 1987, while playing with Tucker, "I decided that just as I would never do anything to harm Tucker, or any of our rescued animals, I also would never do anything to harm any animal, anywhere", and became a vegan.[157] He is a strong supporter of animal rights, and described it as his "day job" other than musical projects.[6][158]

In March 2016, Moby supported the social media campaign #TurnYourNoseUp to end factory farming in association with the nonprofit organization Farms Not Factories.[159]

In 2019, Moby had "Vegan for life" tattooed on his neck. This was followed in November of that year with "Animal rights" tattooed on his arms to commemorate the 32nd anniversary of being vegan.[160] He also had "VX" tattooed next to his right eye, the "V" standing for vegan and the "X" for straight edge, referencing his sobriety.[161]

Drug use

From 1987 to 1995, Moby described his life as a "very clean" one and abstained from drugs, alcohol, and "for the most part", sex.[3] After taking LSD once at nineteen, he started to suffer from panic attacks which he continued to experience but learned to deal with them more effectively.[15] Shortly after his mother died from lung cancer in 1997, Moby recalled that he had "an epiphany" and experimented with alcohol, drugs, and sex which continued for four years after the commercial success of Play.[3][18][29] He became a self-confessed "old-timey alcoholic".[6] During his 18 tour in 2002 he found himself being argumentative and alienating close friends. At the end of the year he wished to make amends and live a healthier lifestyle and promised a girlfriend that he would quit alcohol for one month; he lasted two weeks.[3][162] Moby continued to drink to excess and would ask audiences at concerts to give him drugs. Matters culminated shortly after he turned 43 when he attempted suicide; he had his last drink on October 18, 2008 and has since attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.[163][164][165] In 2016, he said of his sobriety: "Since I stopped and reoriented myself towards things that have meaning, everything has gotten a million times better".[12]

Spirituality and faith

Moby has adopted different faiths throughout his life. He identified himself as an atheist when he was growing up, followed by agnostic, then "a good eight or ten years of being quite a serious Christian", during which time he taught Bible studies.[164] Around 1985, he read the teachings of Christ, including the New Testament and the Gospels and "was instantly struck by the idea that Christ was somehow divine. When I say I love Christ and love the teachings of Christ, I mean that in the most simple and naïve and subjective way. I'm not saying I'm right, and I certainly wouldn't criticize anyone else's beliefs."[166][167][168] In the liner notes of Animal Rights (1996), Moby wrote: "I wouldn't necessarily consider myself a Christian in the conventional sense of the word, where I go to church or believe in cultural Christianity, but I really do love Christ and recognize him in whatever capacity as I can understand it as God. One of my problems with the church and conventional Christianity is it seems like their focus doesn't have much to do with the teachings of Christ, but rather with their own social agenda". In 2014, Moby pointed out that if needed to label himself, it would be as a "Taoist–Christian–agnostic quantum mechanic."[169] In 2019, Moby said that he is not a Christian, "but my life is geared towards God [...] I have no idea who or what God might be."[9]

Charity

Moby is an advocate for a variety of causes, working with MoveOn.org, The Humane Society and Farm Sanctuary, among others. He created MoveOn Voter Fund's Bush in 30 Seconds contest along with singer and MoveOn Cultural Director Laura Dawn and MoveOn Executive Director Eli Pariser. The music video for the song "Disco Lies" from Last Night has heavy anti-meat industrial themes. He also actively engages in nonpartisan activism and serves on the Board of Directors of Amend.org, a nonprofit organization that implements injury prevention programs in Africa.[170]

Moby is a member of the Board of Directors of the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function (IMNF), a not-for-profit organization dedicated to advancing scientific inquiry on music and the brain and to developing clinical treatments to benefit people of all ages.[171] He has also performed on various benefit concerts to help increase awareness for music therapy and raise funds for the Institute. In 2004, he was honored with the IMNF's Music Has Power Award for his advocacy of music therapy and for his dedication and support to its recording studio program.[172]

He is an advocate of net neutrality and he testified before United States House of Representatives committee debating the issue in 2006.[173][174]

In 2007, Moby launched MobyGratis.com, a website of unlicensed music for filmmakers and film students for use in an independent, non-commercial, or non-profit film, video, or short. If a film is commercially successful, all revenue from commercial licence fees granted via Moby Gratis is donated to Humane Society of the United States.[85][164][175]

In 2008, he participated in Songs for Tibet, an album to support Tibet and the Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso.

In April 2009, Moby spoke about his personal experiences of Transcendental Meditation at the David Lynch Foundation benefit concert Change Begins Within benefit concert in New York City.[176] In April 2015, Moby performed "Go" at The Evening of David Lynch tribute event at The Theatre at Ace Hotel in Los Angeles, which highlighted the work of the David Lynch Foundation and raised funds to teach Transcendental Meditation to local youth.[177]

In April 2018, Moby auctioned over 100 pieces of musical equipment via Reverb.com to raise funds for the non-profit organisation Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, thinking it was better to sell it for a good cause rather than in storage.[178] Moby held a second sale for the organisation in June 2018 consisting of his personal record collection, including records that he used to use for DJ sets in his early career and his own personal copy of his albums.[179] A third was held in October 2018 that included the sale of almost 200 analog drum machines, 100 instruments, and his entire vinyl collection.[180]

In 2018, Moby participated in Al Gore's 24-hour broadcast on climate change and environmental issues.[181]

Moby is an advocate for Best Friends; he was part of the No-Kill Los Angeles (NKLA) launch celebration and directed a lyric video for his song “Almost Home" which features dogs and cats from the Best Friends Pet Adoption and Spay/Neuter Center in Mission Hills, California.[182]

Photography

Moby developed an interest in photography at age ten when his uncle, a photographer for The New York Times, gave him a Nikon F camera. He cites Edward Steichen as a major early influence.[183] At 17 he set up a darkroom in his basement and pursued photography while at university. Moby kept his photography private until 2010, when he put some of his work on public display at the Clic Gallery and the Brooklyn Museum in New York City.[183] In May 2011, Moby released a photography book containing pictures that were taken during the Wait for Me tour in 2010 named Destroyed. It was released in conjunction with his same-titled album, and pictures from it were also put on display.[184][185] From October to December 2014, Moby showcased his Innocents collection of large-scale photographs at the Fremin Gallery, featuring a post-apocalyptic theme and a cast of fictitious cult members wearing masks.[186]

Books

In March 2010, Moby and animal activist Miyun Park released Gristle: From Factory Farms to Food Safety (Thinking Twice About the Meat We Eat), a collection of ten essays by various people in the food industry that they edited to detail "unbiased, factual information about the consequences of animal production" and factory farming.[187]

In 2014, Moby announced his decision to write an autobiography covering his life and career from his move to New York City in the late 1980s to the recording of Play in 1999.[188] He enjoyed the experience, and wrote approximately 300,000 words before cutting it by half to reach a rough edit of the book. Porcelain: A Memoir was released on May 17, 2016, by Penguin Press. Moby put out the compilation album Music from Porcelain to coincide the book's release, featuring his own tracks and a mixtape of tracks by other artists.[189]

In October 2018, Moby announced his second memoir, Then It Fell Apart. It was released on May 2, 2019, and covers his life and career from 1999 to 2009.[190] Moby has expressed a wish to write a third.[9]

Discography

Studio albums

- Moby (1992)

- Ambient (1993)

- Everything Is Wrong (1995)

- Animal Rights (1996)

- Play (1999)

- 18 (2002)

- Hotel (2005)

- Last Night (2008)

- Wait for Me (2009)

- Destroyed (2011)

- Innocents (2013)

- Long Ambients 1: Calm. Sleep. (2016)

- These Systems Are Failing (2016)

- More Fast Songs About the Apocalypse (2017)

- Everything Was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt (2018)

- Long Ambients 2 (2019)

Awards

| Year | Awards | Category | Work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | MTV EMA | Best Dance | Himself | Nominated |

| 1999 | Online Music Awards | Best Electronic Fansite[citation needed] | Nominated | |

| 2000 | Q Awards | Best Live Act | Nominated | |

| DanceStar Awards | DanceStar of the Year | Won | ||

| Best Album | Play | Won | ||

| Music Television Awards | Best Male | Himself | Nominated | |

| Best Dance | Nominated | |||

| Best Video | "Natural Blues" | Nominated | ||

| VH1/Vogue Fashion Awards | Visionary Video[191] | Won | ||

| MTV VMA | Best Male Video[192] | Nominated | ||

| MTV EMA | Best Video[193] | Won | ||

| Best Dance | Himself | Nominated | ||

| Best Album[194] | Play | Nominated | ||

| TMF Awards | Best Album International | Won | ||

| Grammy Awards | Best Alternative Music Performance[192] | Nominated | ||

| Best Rock Instrumental Performance[192] | "Bodyrock" | Nominated | ||

| Billboard Music Video Awards | Maximum Vision Award | Nominated | ||

| Dance Clip of the Year | Won | |||

| D&AD Awards | Direction | Wood Pencil | ||

| MVPA Awards | Electronic Video of the Year | "Run On" | Nominated | |

| Viva Comet Awards | Best International Video | "Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad?" | Won | |

| Best Live Act | Himself | Nominated | ||

| Viva Zwei Audience Award | Nominated | |||

| BRIT Awards | Best International Male[195] | Nominated | ||

| NME Awards | Best Solo Artist[196] | Nominated | ||

| Best Dance Act | Nominated | |||

| 2001 | Nominated | |||

| Best Live Act | Won | |||

| My VH1 Music Awards | Best Male[197] | Nominated | ||

| Best Collaboration[197] | "South Side" | Nominated | ||

| Favorite Video[197] | Nominated | |||

| MTV VMA | Best Male Video[192] | Won | ||

| Teen Choice Awards | Choice Dance Track | Nominated | ||

| Grammy Awards | Best Dance Recording[192] | "Natural Blues" | Nominated | |

| NRJ Music Awards | International Male Artist of the Year[198] | Himself | Won | |

| NRJ Music Awards | International Album of the Year[198] | Play | Nominated | |

| IFPI Platinum Europe Awards | Album Title[199] | Won | ||

| 2002 | Won | |||

| Grammy Awards | Best Music Video, Long Form[192] | Nominated | ||

| BMI Pop Songs Awards | Pop Songs[200] | "South Side" | Won | |

| Billboard Music Awards | Electronic Album of the Year[201] | 18 | Won | |

| Electronic Artist of the Year[201] | Himself | Won | ||

| Q Awards | Best Producer[202] | Won | ||

| BMI Film & TV Awards | Certificate of Achievement[203] | Won | ||

| MTV EMA | Web Awards[204] | Won | ||

| Best Dance[204] | Nominated | |||

| Teen Choice Awards | Choice Male Artist | Nominated | ||

| MTV VMA | Best Cinematography[192] | "We Are All Made of Stars" | Won | |

| 2003 | BDS Certified Spin Awards | 300,000 Spins | "South Side" | Won |

| IFPI Platinum Europe Awards | Album Title[205] | 18 | Won | |

| Hungarian Music Awards | Best Foreign Dance Album | Nominated | ||

| Grammy Awards | Best Pop Instrumental Performance[206] | "18" | Nominated | |

| MVPA Awards | Best Electronic Video | "In This World" | Won | |

| Best Directional Debut | Won | |||

| MTV EMA | Best Dance[207] | Himself | Nominated | |

| BRIT Awards | Best International Male[208] | Nominated | ||

| MTV Asia Awards | Best Male[209][210] | Nominated | ||

| MTV VMAJ | Best Dance Video | "We Are All Made of Stars" | Nominated | |

| DanceStar Awards | Best US Act | Himself | Won | |

| 2004 | Outstanding Contribution to Dance Music | Won | ||

| Best Music DVD | 18 B Sides + DVD | Won | ||

| Lunas del Auditorio | Espectaculo Alternativo | Himself | Nominated | |

| 2005 | MTV EMA | Best Male | Nominated | |

| MTV Russian Music Awards | Best International Act | Nominated | ||

| Billboard Music Awards | Top Electronic Artist | Nominated | ||

| Top Electronic Album | Hotel | Nominated | ||

| 2006 | ECHO Awards | Best International Male | Himself | Nominated |

| Lunas del Auditorio | Musica Electronica | Won | ||

| 2007 | MVPA Awards | Best Electronic Video | "New York, New York" | Nominated |

| Best Choreography | Nominated | |||

| NRJ Music Awards | Francophone Duo/Group of the Year | Himself (with Mylene Farmer) | Nominated | |

| 2008 | Music Television Awards | Best Dance | Himself | Nominated |

| 2009 | Grammy Awards | Best Electronic/Dance Album[211] | Last Night | Nominated |

| 2010 | Lunas del Auditorio | Musica Electronica | Himself | Nominated |

| 2011 | Hungarian Music Awards | Electronic Music Production of the Year | Nominated | |

| 2015 | Veggie Awards | Person of the Year[212] | Won | |

| 2017 | Webby Awards | Animation[213] | Won | |

| 2018 | UK Music Video Awards | Best Urban Video - International | "ASAP Forever" (with ASAP Rocky) | Nominated |

| Best Colour Grading in a Video | Nominated | |||

| 2019 | GAFFA-Prisen Awards | Best International Album | Everything Was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt | Pending |

| Best International Artist | Himself | Pending |

References

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Moby". Allmusic. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Moby Didn't Feel Pressure To Follow Up 'Play,' '18' Bows At Number Four". December 13, 2006. Archived from the original on December 13, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Duerden, Nick (March 5, 2005). "Moby: 'I am a messy human being, and I don't have a problem admitting". The Independent. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ a b McGrath, Nick (January 31, 2014). "Moby: My family values". The Guardian. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "Genealogy of Claire and Alex Jamison". Cujamison.home.comcast.net. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Sawyer, Miranda (May 21, 2016). "Moby: 'There were bags of drugs, I was having sex with a stranger'". The Guardian. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Catlin, Roger (March 12, 1995). "Moby: Remixed, repulsed...reborn?". The Hartford Courant. Connecticut. pp. G1, G4. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Moby in Scheerer, Mark (February 9, 2000). "DJ Moby finds inspiration in old Southern music". CNN. Archived from the original on September 22, 2006.

The basis for Richard Melville Hall — and for Moby — is that supposedly Herman Melville was my great-great-great-granduncle.

- ^ a b c Voynovskaya, Nastia (April 23, 2019). "How It 'Fell Apart': Moby Talks New Memoir, Addiction and Trauma". KQED. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Wadler, Joyce (April 27, 2011). "At Home With Moby in a Hollywood Hills Castle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Anderman, Joan (October 19, 2000). "Accidental Rock Star? Moby's Mix Plays Well". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Pires, Candice (November 26, 2016). "Moby: 'I was disappointed to be heterosexual'". The Guardian. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Bennun, David (Summer 2000). "Moby". Hot Air. Retrieved April 14, 2019 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ a b c "Is Moby's Music Still Good When Its Free?". National Public Radio. March 31, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Lawson, Willow (September 1, 2004). "The Sounds of Moby". Psychology Today. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "Moby reuniting w/ Vatican Commandos for a CT NYC hardcore show + D.I. dates, boat shows, 45 Grave, Jello & more". Brooklyn Vegan. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Gordon, Jeremy (November 6, 2013). "Moby on Moby". Vice.com. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marzorati, Gerald (March 17, 2002). "All by Himself". The New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Gurliacci, David (May 12, 2016). "Moby, a Former Darien Resident, Coming to Stamford to Talk About His New Memoir". Darienite. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Monk, Katherine (June 22, 1995). "Moby there's a better way". The Vancouver Sun. p. C8. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Gross, Jason (September 1997). "Moby: Interview by Jason Gross (September 1997)". Perfect Sound Forever. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Catlin, Roger (March 5, 1997). "Moby returns to rock after techno years". The Hartford Courant. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Brune, Adrian (October 18, 2005). "Little idiot makes it big". The Hartford Courant. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Moby – In His Words..." Mercury Wheels. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Beta, Andy (July 1, 2012). "An Interview with Moby". The Believer. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "120 REASONS TO LIVE: ULTRA VIVID SCENE". Magnet. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Buckley, Peter (2003). The Rough guide to rock : [the definitive guide to more than 1200 artists and bands] (3rd ed.). London: Rough Guides. p. 683. ISBN 978-1843531050. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Peanuts (Media notes). Shopwell. Not on Label. 1990. HF-01.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Lester, Paul (June 16, 2000). "Jesus of suburbia". The Guardian. p. 54. Retrieved April 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Ostroff, Joshua (June 1, 2002). "Moby: A Whale of a Tale". Exclaim!. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Eric Härle (March 25, 2003). "Interview with ERIC HÄRLE, manager at DEF for Moby, Sonique, Röyksopp — Mar 25, 2003". HitQuarters (Interview). Interviewed by Kimbel Bouwman. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Ressler, Darren (October 16, 2016). "Read a 2008 interview with Moby & Ryuichi Sakamoto". Big Shot. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "The Brotherhood: Time's Up". Moby.org. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c Kot, Greg (August 2, 1992). "Breakfast with Moby, techno's reigning wizard". Chicago Tribune. p. 19. Retrieved April 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Weisbard, Eric (March 1997). "Moby: Tech no!". Spin. Retrieved April 14, 2019 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Flick, Larry (October 24, 1992). "Moby Sails New Techno Waters; Owens In The Black". Billboard. 104 (43): 34. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Martin 2001, p. 70.

- ^ "biography". moby.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ a b c Gourley, Bob (1993). "Moby". Chaos Control Digizine. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Gourley, Bob (1999). "Moby". Chaos Control Digizine. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- ^ "Moby". LifeAndLove.tv. Archived from the original on November 19, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ Demons/Horses (Media notes). Voodoo Child. NovaMute. 1994. 12 NoMu 32.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005". Spin Magazine. June 20, 2005. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c Ali, Lorraine (July 1, 1995). "Superstardom remains elusive for Moby". The Los Angeles Times. p. F10. Retrieved April 14, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Norris, Chris (March 27, 1995). "Call Me Moby". New York Magazine. p. 48. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Daly, Joe (August 3, 2013). "Moby: The Interview". Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Ali, Lorraine (January 19, 1997). "Cut the Beat, Crank Up the Guitar". Los Angeles Times. p. 80. Retrieved April 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Levine, Robert (February 9, 1997). "Moby gets out of his depth". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 42. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Chirazi, Steffan (August 24, 1997). "Pop Quiz: Q&A with Moby". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 51. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Scribner, Sara (September 10, 1997). "Under the Big Top". The Los Angeles Times. p. 21. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Corcoran, Michael (October 21, 1997). "Moby scores with mix of soothers and seethers". Austin American-Statesman. p. E1. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Eakin, Marah. "Moby: I Like To Score · The A.V. Club". Avclub.com. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Peiken, Matt (December 5, 1997). "Multitalented Moby proves he 'Likes to Score'". Albuquerque Journal. p. B4. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Katz, Larry (October 22, 1999). "Moby's second coming". The Record. p. 17. Retrieved April 16, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (August 10, 1999). "He sees no borders". The Los Angeles Times. p. F1, F12. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Becker, Scott Marc (June 8, 1999). "Sharps & flats". Salon.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Armor, Jerry (May 22, 2002). "Moby Didn't Feel Pressure To Follow Up 'Play,' '18' Bows At Number Four". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on December 13, 2006. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ Roberts, Chris (September 2003). "Moby". Bang. Retrieved April 14, 2019 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Gareth Grundy. "Moby licenses every track on Play. Ker-ching! | Music". The Guardian. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Wyman, Bill (October 14, 2007). "How to Calculate Musical Sellouts". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Gone in 60 Seconds Soundtrack (2000)". Moviemusic.com. June 6, 2000. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Moby: Play - The DVD". IMDb.com. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Ethan (May 1, 2002). "Organization Moby". Wired. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Steven J. (October 12, 2016). "Moby Talks 'Fast Post-Punk' LP, Embracing Commercial Irrelevance". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ "Moby – Wait For Me". Genero.tv. April 6, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "Moby Unveils Plans For Area: One Festival". Billboard. October 19, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Moby Attacked In Boston". Billboard. December 12, 2002. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (May 12, 2002). "What Do You See, Moby?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "i've recorded a new version of 'extreme ways' for the bourne legacy". moby.com. July 31, 2012. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Moby records new version of 'Extreme' closing theme for upcoming 'Bourne Legacy'". New York Daily News. August 1, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Gold, Kerry (August 16, 2002). "Moby fires back at Eminem: 'He has a crush on me'". The Ottawa Citizen. p. F7. Retrieved April 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Entertainment | Damp end for 2003 Glastonbury". BBC News. June 30, 2003. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (January 28, 2004). "Back to the dance floor for Moby". Los Angeles Times. p. E6. Retrieved May 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "make love fuck war". moby.com. July 2, 2004. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Moby: The Very Best of Interview". Shakenstir. 2006. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ David Peschek (March 11, 2005). "CD: Moby, Hotel | Music". The Guardian. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Christie's No. 1 On Reconfigured U.K. Chart". Billboard. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Ryan, Patrick (December 24, 2014). "Song premiere: Moby gives 'Live Forever' new life". USA Today. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "BFI | Film & TV Database | SOUTHLAND TALES (2005)". Ftvdb.bfi.org.uk. April 16, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Moby Shows His Natural Blues With New Band The Little Death (review) " Time to play b-sides". Playbsides.com. January 15, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "Moby signs deal with Mute Records". June 15, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "moby announces new nyc club night". moby.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ "degenerates returns for special cmj party in nyc". moby.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Moby (December 5, 2007). "new album – last night". moby.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Palmer, Tamara (November 3, 2008). "Moby: The Fly Life". SuicideGirls. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c Moby (April 14, 2009). "wait for me". moby.com. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "i just finished mixing my next record. as i wrote earlier, hopefully it will be released next june". moby.com. February 13, 2009. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Moby (March 19, 2009). "if you're in the music business (and for your sake i hope you're not...) you probably know about bob lefsetz". moby.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ David Lynch and Moby: Music & Abandoned Factories (Video). David Lynch Foundation. April 15, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Moby (April 19, 2010). "Video Competition: Winner Announced!". moby.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Moby to release Remix Album "Wait For Me. Remixes"". idiomag. March 23, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Moby (April 25, 2009). "thanks for coming to the issue project room fundraiser friday". moby.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Moby to donate concert profits to domestic violence charity". Side-Line. October 6, 2009.

- ^ "Falls Festival Day 4 @ Lorne, Victoria (31/12/2009)". Fasterlouder.com.au. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "Sunset Sounds at Riverstage (Brisbane, Queensland) on 6 Jan 2010 –". Last.fm. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ Perry, Clayton (June 2, 2010). "Interview: Moby – Singer, Songwriter and Producer". Clayton Perry's Interview Exclusives. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Tewksbury, Drew (July 6, 2010). "Moby gets back to his roots with Diamondsnake". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Moby (January 20, 2010). "i've decided to start work on the next record". moby.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Moby (February 15, 2011). "ok, ta-da, official next album announcement update. my next album is called 'destroyed' and it comes out in the middle of may sometime". moby.com. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "destroyed". moby.com. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ Moby (June 24, 2011). "We need another single from 'destroyed'. What should it be?". moby.com. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Moby (September 2, 2011). "So, per your choice(s)-next single(s) will be 'after' and 'the right thing'. Thanks for choosing. Videos and remixes to follow". Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Find Your True North". Wanderlust Festival. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "1 World Music Festival". 1 World Music Festival. September 19, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Movement Electronic Music Festival – May 25,26,27, 2013 – Hart Plaza, Detroit". Movement.us. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "MUTE • Moby • - DJing the Sahara Tent at Coachella 2013: 4/13 & 4/20". Mute.com. January 25, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Moby and Mark Lanegan's 'The Lonely Night' VIDEO". Bowery Boogie. May 2, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "iTunes – Music – The Lonely Night (Remixes) – EP by Moby & Mark Lanegan". Itunes.apple.com. April 23, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Mital, Sachyn (September 29, 2013). "Going Wrong: An Interview with Moby". Pop Matters. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "innocents – new album from moby". moby.com. April 15, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Moby and Wayne Coyne Issue Casting Call for Nude Skaters, S&M Gimp | SPIN | Newswire". SPIN. August 6, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "some people had been asking: why the fonda? why only 3 shows?". moby.com. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Charlie Countryman Soundtrack List". Soundtrack Mania. February 15, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Cathedrals of Culture: Berlin Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Moby Announces New Album These Systems Are Failing, Shares New Song: Listen | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Winner: Are you lost in the world like me". webbyawards.com/. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (October 17, 2016). "See Moby's Grim New Video About Smartphone Addiction". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "moby & the void pacific choir announce debut album 'these systems are failing'". moby.com. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Moby & the Void Pacific Choir: These Systems Are Failing Album Review". pitchfork.com. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "moby announces circle v festival. shares new video from void pacific choir". moby.com. August 23, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "moby releases surprise album". billboard.com. June 14, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "Moby Announces Trip-Hop-Inspired New Album Everything Was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt". billboard.com. December 11, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Eric Renner (February 27, 2018). "Moby says new album explores 'who we are as a species'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ "Moby Announces New Album Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt". Mute Records. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ "Watch Moby's Post-Apocalyptic 'Mere Anarchy' Video". rollingstone.com. January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Video: Moby – "This Wild Darkness"". spin.com. February 26, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Shackleford, Tom (December 14, 2017). "Moby announces spring 'tour' dates in Los Angeles and New York". AXS. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Pointing, Charlotte (March 2, 2018). "Vegan Celeb Moby to Donate 100% of Album Profits to Animal Rights". LIVEKINDLY. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Zellner, Xander. "Moby Scores First Hot 100 Entry Since 2001, With A$AP Rocky". Billboard. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ "Heather Graham's 'Half Magic' to Feature New Songs by Moby | Film Music Reporter". Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Yannik PROVOST. "Bleu Noir". Innamoramento.net. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Jean Michel Jarre. "ELECTRONICA 1: The Time Machine". ELECTRONICA 1: The Time Machine. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Moby Announces New Album These Systems Are Failing, Shares New Song: Listen - Pitchfork".

- ^ McClure, Kelly. "Moby on 'Blunt Talk,' His New Restaurant, and His Sixth Sense". Maxim. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Nile Rodgers, Noel Gallagher, TLC, More Featured in New Netflix Documentary Series". Spin. July 28, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "little idiot collective opens". alex eben meyer. Wordpress. October 30, 2004. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Elyssa Lee, Rob Turner (December 1, 2004). "Moby, Remixed". Inc.com. Mansueto Ventures. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Sarah van Schagen (November 29, 2006). "Moby reflects on his new "best of" album and his not-so-new social activism". grist.org. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ^ Jenn Harris (November 9, 2015). "Moby dishes on Little Pine, his new vegan restaurant in Silver Lake". Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Lesley Balla (November 20, 2015). "Moby's Little Pine Vegan Restaurant Debuts in Silver Lake". Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Hochman, David (May 9, 2016). "Talking To Moby About His New Memoirs And Giving Money To Animals". Forbes. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- ^ Javorsky, Nicole (November 18, 2019). "Moby launches lifestyle line to support animal rights". The Hill. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ Moby (August 23, 2016). "moby announces circle v festival. shares new video from void pacific choir". Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ Vegan Event Hub (August 23, 2016). "CIRCLE V FESTIVAL – MOBY USA". Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ LA Weekly (September 12, 2017). "Circle V Vegan and Animal Rights Festival Returns With Moby, Waka Flocka Flame". Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ Sperounes, Sandra (May 11, 2002). "To blog or not to blog". Edmonton Journal. p. 41. Retrieved April 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Zenko, Darren (March 9, 2008). "How Dungeons & Dragons creator Gygax created the modern nerd". Toronto Star. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Gove, Michael (March 11, 2008). "Et in Orcadia ego: confessions of a D & D addict". The Times. UK. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Carlson, Jen (June 9, 2014). "Inside The "Tiny" Mott Street Apartment Moby Just Sold For $2 Million". Gothamist. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ McLaughlin, Katy (September 10, 2015). "Moby Downsizes in Los Angeles". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "Celeb video: 'I am Bradley Manning' – Patrick Gavin". Politico.Com. June 20, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "I am Bradley Manning (full HD)". YouTube. June 18, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ Joyce, Kathleen (January 13, 2018). "Moby claims CIA asked him to post about Trump and Russia". Fox News. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ McShane, Larry (January 13, 2018). "Moby doubles down on Trump's Russia ties, which he says he learned about from CIA agent friends". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ Savage, Mark (May 21, 2019). "Natalie Portman denies Moby's 'creepy' dating claims". BBC. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ Ressler, Darren (August 11, 2014). "Moby interviewed by his remixers". Big Shot. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Chiorando, Maria (November 23, 2017). "Moby shares photo of kitten who turned him vegan exactly 30 years ago". Plant Based News. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "One on One with Moby". Vegetarian Times. February 23, 2011. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Celebrities back campaign to end 'inhumane' treatment of pigs in 'factory farms'". Independent.ie..

- ^ Barr, Sabrina (November 13, 2019). "Musician Moby has 'Animal Rights' tattooed on his arms to mark 32 years as a vegan". The Independent. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Chiorando, Maria (December 16, 2019). "Moby Explains Meaning Behind Vegan Face Tattoo". Plant Based News. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ Getlen, Larry (April 26, 2019). "How Moby went from partying with A-listers to begging concertgoers for drugs". New York Post. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Paul Lester. "Moby: 'Going to AA is the only chance in LA you get to see fellow musicians' | Music". theguardian.com. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c Dalton, Stephen (May 9, 2011). ""The Humility That Comes From Being Hated": Moby Interviewed". The Quietus. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ St. Clair, Josh (May 10, 2019). "How Moby Got Famous, Hit Rock Bottom, and (Ultimately) Found Redemption". Men's Health. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ "BBC – Press Office – Moby World Service interview". BBC World Service. April 29, 2003. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Is Moby a Christian?". Christianity Today. January–February 2003. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Moby: Everything is Complicated. Sojourners Magazine (Audio interview). September 20, 2006. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Jaeah (September 2, 2014). "Exclusive Premiere of Moby's New Video, 'The Last Day'". Mother Jones.

- ^ "About Amend.org". Amend.org. Archived from the original on February 7, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "About the Institute". Institute for Music and Neurologic Function. Archived from the original on December 4, 2003. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Moby. "Moby biography, net worth, quotes, wiki, assets, cars, homes and more". Bornrich.com. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ Save the Internet | Join the fight for Internet Freedom

- ^ "Rep. Markey, Moby Speak Out for Internet Freedom, Against Corporate Web Takeover". Free Press. May 18, 2006. Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Dominic, Radcliffe. "MobyGratis Grows to Help Indie Filmmakers". littlewhitelies. Archived from the original on September 1, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Bienfaits Meditation (April 3, 2009). "The "Change Begins Within" Press Conference for the benefit of the David Lynch Foundation to teach 1 million at risk kids Transcendental Meditation". Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Tim Grierson (April 2, 2015). "Duran Duran, Flaming Lips Play Surreal 'Music of David Lynch' Tribute - Artists from Sky Ferreira to Moby offer electric interpretations of the director's soundtracks". Rolling Stone magazine. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Moby to Sell Synth Collection on Reverb, Donate Proceeds". reverb.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Eede, Christian (June 13, 2018). "Moby Selling Record Collection For Charity". The Quietus.

- ^ Blistein, Jon; Blistein, Jon (October 4, 2018). "Moby Selling Massive Drum Machine Collection for Charity". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ http://www.washingtontimes.com, The Washington Times. "Al Gore to host 24-hour climate change special featuring Moby, Goo Goo Dolls". The Washington Times. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

{{cite web}}: External link in|last= - ^ "Moby". Best Friends Animal Society. August 28, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Noble, Lou (May 29, 2014). "Interviews – Moby". The Photographic Journal. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Graff, Gary (April 20, 2011). "Moby Preps Release of 'Destroyed' Album/Photo Book". Billboard. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Cheng, Scarlet (July 2, 2014). "Moby: Apocalypse Already". Artillery Magazine. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Corwin, William (December 18, 2014). "MOBY Innocents". The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ "Militant to Dilettante Vegan: Moby & Miyun Park's "Gristle"". Vegsource. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ "Moby to write memoir spanning first decade of his career". Fact Mag. June 11, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Leight, Elias (April 28, 2016). "Moby Talks 'Porcelain' Memoir, Announces New Compilation Album: Exclusive". Billboard. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Daly, Rhian (October 14, 2018). "Moby announces new memoir, 'Then It Fell Apart'". NME. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "VH1 VOGUE FASHION AWARDS 2001". Vh1.com. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Moby". Rock On The Net. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Basham, David (November 17, 2000). "Madonna, Eminem Lead American Romp Through Europe Music Awards – Music, Celebrity, Artist News". MTV.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "Articles – MTV Europe Music Awards 2000". UKMIX. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "In Depth | Brit Awards | Brits 2000: The winners". BBC News. March 3, 2000. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ http://www.rocklistmusic.co.uk/2000.html

- ^ a b c "VH1 and VH1.com Announces Mick Jagger, Creed, Sting, Nelly Furtado, Lenny Kravitz, Destiny's Child and No Doubt to Perform at 'My VH1 Music Awards '01,' Live December 2nd at 9PM ET/PT" (Press release). January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2013 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ a b Olivier, Ellen (August 30, 2013). "Moby the artist and the whale star at a party to support Library Foundation". latimes.com. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 2002". Ifpi.org. September 1, 2005. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "2002 BMI Pop Awards: Song List | News". BMI.com. May 13, 2002. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ a b "2002 BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS". Billboard. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "Entertainment | Q Awards 2002: Winners". BBC News. October 14, 2002. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "BMI Honors Top Film, Television and Cable Composers and Songwriters at Annual Film & Television | Press". BMI.com. May 15, 2002. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ a b "MTV Europe Music Awards 2002 Nominations". Billboard. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 2002". Ifpi.org. September 1, 2005. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "Grammy Awards: Best Pop Instrumental Performance". Rock On The Net. Retrieved November 19, 2013.