1960 United States presidential election: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Campaign issues: Rewriting using text from History of Roman Catholicism in the United States |

||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

===Campaign issues=== |

===Campaign issues=== |

||

A key factor that hurt Kennedy in |

A key factor that hurt [[John F. Kennedy]] in his campaign was the widespread prejudice against his [[Roman Catholic]] religion; some [[Protestants]] believed that, if he were elected President, Kennedy would have to take orders from the [[Pope]] in [[Rome]]. To address fears that his Roman Catholicism would impact his decision-making, [[John F. Kennedy]] famously told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters — and the Church does not speak for me."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/jfkhoustonministers.html|title=Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association|accessdate=2007-09-17|last=Kennedy|first=John F.|date=2002-06-18|work=American Rhetoric}}</ref> He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy also raised the question of whether one-quarter of Americans were relegated to second-class citizenship just because they were Roman Catholic. Even so, it was widely believed after the election that Kennedy lost some heavily Protestant states because of his Catholicism. |

||

However, Kennedy's campaign did take advantage of an opening when the Rev. [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]], the civil-rights leader, was arrested in Georgia while leading a civil rights march. Nixon refused to become involved in the incident, but Kennedy placed calls to local political authorities to get King released from jail, and he also called King's father and wife. As a result, King's father endorsed Kennedy, and he received much favorable publicity in the black community. On election day, Kennedy won the black vote in most areas by wide margins, and this may have provided his margin of victory in states such as [[New Jersey]], [[South Carolina]], [[Illinois]], and [[Missouri]]. As the campaign moved into the final two weeks, the polls and most political [[pundits]] predicted a Kennedy victory. However, President Eisenhower, who had largely sat out the campaign, made a vigorous campaign tour for Nixon over the last 10 days before the election. Eisenhower's support gave Nixon a badly needed boost, and by election day the polls indicated a virtual tie. |

|||

===Results=== |

===Results=== |

||

Revision as of 05:35, 30 March 2009

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

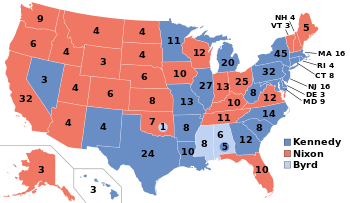

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Kennedy/Johnson, Red denotes those won by Nixon/Lodge. Orange denotes the electoral votes for Harry F. Byrd by Alabama and Mississippi unpledged electors, and an Oklahoma "faithless elector". Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1960 marked the end of Dwight D. Eisenhower's two terms as President. Eisenhower's Vice President, Richard Nixon, who had transformed his office into a national political base, was the Republican candidate.

The Democrats nominated Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy (JFK). He would become the first Roman Catholic to be elected President, and he remains the only Roman Catholic to be elected to the Presidency. The electoral vote was the closest in any presidential election dating to 1916, and Kennedy's margin of victory in the popular vote is among the closest ever in American history. The 1960 election also remains a source of debate among some historians as to whether vote theft in selected states aided Kennedy's victory.[1]

This was the first election in which Alaska and Hawaii were included in the election, having been granted statehood on January 3 and August 21 of the previous year. It was also the first election in which both candidates for president were born in the 20th century.

Nominations

Democratic Party

Democratic candidates

- John F. Kennedy, U.S. senator from Massachusetts

- Lyndon B. Johnson, U.S. Senate Majority Leader from Texas

- Hubert H. Humphrey, U.S. senator from Minnesota

- Adlai E. Stevenson, former U.S. governor of Illinois

- Stuart Symington, U.S. senator from Missouri

Candidates gallery

-

Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota

-

Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri

A number of political leaders were candidates for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination. However, with the exceptions of Kennedy, Senator Lyndon Johnson of Texas, Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri and former Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson,[2] the rest of the presidential hopefuls were regional "favorite son" candidates without any realistic chance of winning the nomination. Symington, Stevenson, and Johnson all refused to campaign in the presidential primaries, thus limiting their chances of winning the nomination. All three men hoped that the other leading candidates would stumble in the primaries, thus causing the Democratic Convention's delegates to choose them as a "compromise" candidate acceptable to all factions of the party.

Kennedy was initially dogged by suggestions from some Democratic Party elders (such as former President Harry Truman, who was supporting Symington) that he was too youthful and inexperienced to be president; these critics suggested that he should agree to be the running mate for a "more experienced" Democrat. Realizing that this was a strategy touted by his opponents to keep the public from taking him seriously, Kennedy stated frankly, "I’m not running for vice president, I’m running for president."[3]

A problem for Kennedy was his Roman Catholic religion. Recalling the experience of 1928 Catholic Democratic presidential nominee Al Smith, many wondered if anti-Catholic prejudice would hurt Kennedy's chances of winning the nomination and the election in November. To prove his vote-getting ability, Kennedy challenged Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey, a liberal, in the Wisconsin primary. Although Kennedy defeated Humphrey in Wisconsin, the fact that his margin of victory came mostly from heavily Catholic areas left many party bosses unconvinced of Kennedy's appeal to non-Catholic voters. Kennedy next faced Humphrey in the heavily Protestant state of West Virginia, where anti-Catholic bigotry was said to be widespread. Humphrey's campaign was low on money and could not compete with the well-organized, well-financed Kennedy team. Kennedy's attractive sisters, brothers, and wife Jacqueline combed the state looking for votes, leading Humphrey to complain that he "felt like an independent merchant competing against a chain store".[4] Kennedy followed a strong performance in the first televised debate of 1960[5] by soundly defeating Humphrey with over 60% of the vote. Humphrey withdrew from the race and Kennedy gained the victory he needed to prove to the party's bosses that a Catholic could win in a non-Catholic state. Although Kennedy had only competed in nine presidential primaries,[6] the failure of Kennedy's other main rivals - Johnson and Symington - to campaign in any primaries prevented them from claiming that they were popular vote-getters outside their home states. Although Stevenson had been the Democratic Party's presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956 and still retained a loyal following of liberals and intellectuals, his two landslide defeats to Republican Dwight Eisenhower led most party bosses to look for a "fresh face" who had a better chance of winning the general election in November. In the months leading up to the Democratic Convention, Kennedy traveled around the nation persuading delegates from various states to support him. However, as the convention opened, Kennedy was still a few dozen votes short of victory.

Democratic convention

The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles. In the week before the convention opened, Kennedy received two new challengers when Lyndon B. Johnson, the powerful Senate Majority Leader from Texas, and Adlai Stevenson II, the party's nominee in 1952 and 1956, officially announced their candidacies (they had both privately been working for the nomination for some time). However, neither Johnson nor Stevenson were a match for the talented and highly efficient Kennedy campaign team led by Robert Kennedy. Johnson challenged Kennedy to a televised debate before a joint meeting of the Texas and Massachusetts delegations; Kennedy accepted. Most observers felt that Kennedy won the debate, and Johnson was not able to expand his delegate support beyond the South. Stevenson's failure to publicly launch his candidacy until the week of the convention meant that many liberal delegates who might have supported him were already pledged to Kennedy, and Stevenson - despite the energetic support of former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt - was unable to break their allegiance to JFK. Kennedy won the nomination on the first ballot.

Then, in a move which surprised many, Johnson was asked by Kennedy to be his running mate. To this day there is much debate regarding the details of Johnson's nomination - why it was offered and why he agreed to take it. Some historians speculate that Kennedy actually wanted someone else (such as Senators Stuart Symington or Henry M. Jackson) to be his running mate, and that he offered the nomination to Johnson first only as a courtesy to the powerful Senate Majority Leader. According to this theory, Kennedy was then surprised when Johnson accepted second place on the Democratic ticket. Another related story is that, after Johnson accepted the offer, Robert Kennedy went to Johnson's hotel suite to pressure Johnson into declining the vice-presidential offer. Johnson was offended that "JFK's kid brother" would brashly tell him to stay off the ticket. In response to his blunt confrontation with Robert Kennedy, Johnson called JFK to confirm that the vice-presidential nomination was his; JFK claimed that his brother Robert "wasn't aware of recent developments" and clearly stated that he wanted Johnson as his running mate. Both Johnson and Robert Kennedy became so embittered by the experience that they began a fierce personal and political feud that would have grave implications for the Democratic Party in the 1960s.

Norman Mailer attended the convention and wrote his famous profile of Kennedy, "Superman Comes to the Supermarket," published in Esquire.[7]

| John F. Kennedy | 806 |

|---|---|

| Lyndon Johnson | 409 |

| Stuart Symington | 86 |

| Adlai Stevenson | 79.5 |

| Robert B. Meyner | 43 |

| Hubert Humphrey | 41 |

| George A. Smathers | 30 |

| Ross Barnett | 23 |

| Herschel Loveless | 2 |

| Pat Brown | 1 |

| Orval Faubus | 1 |

| Albert Rosellini | 1 |

Republican Party

- Richard Nixon, U.S. vice president from California

- Nelson Rockefeller, U.S. governor of New York

- Barry Goldwater, U.S. senator from Arizona

With the ratification of the 22nd Amendment in 1951, President Dwight D. Eisenhower could not run for the office of President again; he had been elected in 1952 and 1956.

In 1959, it looked as if Vice President Richard Nixon might face a serious challenge for the GOP nomination from New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the leader of the GOP's moderate-liberal wing. However, Rockefeller announced that he would not be a candidate for president after a national tour revealed that the great majority of Republicans favored Nixon.

After Rockefeller's withdrawal, Nixon faced no significant opposition for the Republican nomination. At the 1960 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Nixon was the overwhelming choice of the delegates, with conservative Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona receiving 10 votes from conservative delegates. Nixon then chose former Massachusetts Senator and United Nations Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. as his Vice Presidential candidate. Nixon chose Lodge because his foreign-policy credentials fit into Nixon's strategy to campaign more on foreign policy than domestic policy, which he believed favored the Democrats.

General election

Campaign promises

During the campaign Kennedy charged that under Eisenhower and the Republicans the nation had fallen behind the Soviet Union in the Cold War, both militarily and economically, and that as President he would "get America moving again." Nixon responded that, if elected, he would continue the "peace and prosperity" that Eisenhower had brought the nation in the 1950's. Nixon also argued that with the nation engaged in the Cold War with the Soviets, that Kennedy was too young and inexperienced to be trusted with the Presidency.

Campaign events

Both Kennedy and Nixon drew large and enthusiastic crowds throughout the campaign.[8] In August 1960, most polls gave Vice-President Nixon a slim lead over Kennedy, and many political pundits regarded Nixon as the favorite to win. However, Nixon was plagued by bad luck throughout the fall campaign. In August, President Eisenhower, who had long been ambivalent about Nixon, held a televised press conference in which a reporter, Charles Mohr of Time, mentioned Nixon's claims that he had been a valuable administration insider and adviser. Mohr asked Eisenhower if he could give an example of a major idea of Nixon's that he had heeded. Eisenhower responded with the flip comment, "If you give me a week, I might think of one."[9] Although both Eisenhower and Nixon later claimed that Ike was merely joking with the reporter, the remark hurt Nixon, as it undercut his claims of having greater decision-making experience than Kennedy. The remark proved so damaging to Nixon that the Democrats turned Eisenhower's statement into a television commercial criticizing Nixon.

At the Republican Convention, Nixon had pledged to campaign in all 50 states. This pledge backfired when, in August, Nixon injured his knee on a car door while campaigning in North Carolina; the knee became infected and Nixon had to cease campaigning for two weeks while the infected knee was injected with antibiotics. When he left Walter Reed Hospital, Nixon refused to abandon his pledge to visit every state; he thus wound up wasting valuable time visiting states that he had no chance to win, or which had few electoral votes and would be of little help in the election. For example, in his effort to visit all 50 states, Nixon spent the vital weekend before the election campaigning in Alaska, which had only three electoral votes, while Kennedy campaigned in large states such as New Jersey, Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

Despite the reservations Robert Kennedy had about Johnson's nomination, choosing Johnson as JFK's running mate proved to be a masterstroke for his older brother. Johnson vigorously campaigned for JFK and was instrumental in helping the Democrats to carry several Southern states skeptical of Kennedy, especially Johnson's home state of Texas. On the other hand Ambassador Lodge, Nixon's running mate, ran a lethargic campaign and made several mistakes which hurt Nixon. Among them was a pledge - not approved by Nixon - that as President Nixon would name a black person to his cabinet; the remark offended many blacks who saw it as a clumsy attempt to win their votes, while many Southern whites who still supported racial segregation and may have voted for Nixon were also angered.

Debates

The key turning point of the campaign were the four Kennedy-Nixon debates; they were the first presidential debates held on television, and thus attracted enormous publicity. Nixon insisted on campaigning until just a few hours before the first debate started; he had not completely recovered from his hospital stay and thus looked pale, sickly, underweight, and tired. He also refused makeup for the first debate, and as a result his beard stubble showed prominently on the era's black-and-white TV screens. Nixon's poor appearance on television in the first debate is reflected by the fact that his mother called him immediately following the debate to ask if he was sick. Kennedy, by contrast, rested before the first debate and appeared tanned, confident, and relaxed during the debate. An estimated 80 million viewers watched the first debate. Most people who watched the debate on TV believed Kennedy had won while radio listeners (a smaller audience) believed Nixon had won. After it had ended polls showed Kennedy moving from a slight deficit into a slight lead over Nixon. For the remaining three debates Nixon regained his lost weight, wore television makeup, and appeared more forceful than his initial appearance. However, up to 20 million fewer viewers watched the three remaining debates than the first debate. Political observers at the time believed that Kennedy won the first debate,[10] Nixon won the second[11] and third debates,[12] and that the fourth debate,[13] which was seen as the strongest performance by both men, was a draw.

Campaign issues

A key factor that hurt John F. Kennedy in his campaign was the widespread prejudice against his Roman Catholic religion; some Protestants believed that, if he were elected President, Kennedy would have to take orders from the Pope in Rome. To address fears that his Roman Catholicism would impact his decision-making, John F. Kennedy famously told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters — and the Church does not speak for me."[14] He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy also raised the question of whether one-quarter of Americans were relegated to second-class citizenship just because they were Roman Catholic. Even so, it was widely believed after the election that Kennedy lost some heavily Protestant states because of his Catholicism.

However, Kennedy's campaign did take advantage of an opening when the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., the civil-rights leader, was arrested in Georgia while leading a civil rights march. Nixon refused to become involved in the incident, but Kennedy placed calls to local political authorities to get King released from jail, and he also called King's father and wife. As a result, King's father endorsed Kennedy, and he received much favorable publicity in the black community. On election day, Kennedy won the black vote in most areas by wide margins, and this may have provided his margin of victory in states such as New Jersey, South Carolina, Illinois, and Missouri. As the campaign moved into the final two weeks, the polls and most political pundits predicted a Kennedy victory. However, President Eisenhower, who had largely sat out the campaign, made a vigorous campaign tour for Nixon over the last 10 days before the election. Eisenhower's support gave Nixon a badly needed boost, and by election day the polls indicated a virtual tie.

Results

The election on November 8 remains one of the most famous election nights in American history. Nixon watched the election returns from his suite at the famed Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, while JFK watched the returns at the Kennedy family compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. As the early returns poured in from large Northern and Midwestern cities such as Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Chicago, Kennedy opened a large lead in the popular and electoral vote, and appeared headed for victory. However, as later returns came in from rural and suburban areas in the Midwest, the Rocky Mountain states, and the Pacific Coast states, Nixon began to steadily close the gap with Kennedy. Before midnight, The New York Times had gone to press with the headline "Kennedy Elected President". As the election again became too close to call, Times managing editor Turner Catledge hoped that, as he recalled in his memoirs, "a certain Midwestern mayor would steal enough votes to pull Kennedy through", thus allowing the Times to avoid the embarrassment of having announced the wrong winner, as the Chicago Tribune had memorably done twelve years earlier in announcing that Thomas E. Dewey had defeated President Truman. [1]

It was not until the afternoon of Wednesday, November 9 that Nixon finally conceded the election, and Kennedy claimed victory. A sample of how close the election was can be seen in California; Kennedy appeared to have carried the state by 37,000 votes when all of the voting precincts reported, but when the absentee ballots were counted a week later, Nixon came from behind to win the state by 36,000 votes.[15] Similarly, in Hawaii, it had appeared Nixon had won the state (it was actually called for him early Wednesday morning), but in a recount Kennedy was able to come from behind and win the state by an extremely narrow margin of 115 votes. In the national popular vote, Kennedy beat Nixon by just one tenth of one percentage point (0.1%) - the closest popular-vote margin of the 20th century. In the electoral college, Kennedy's victory was larger, as he took 303 electoral votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win). A total of 15 electors - eight from Mississippi, six from Alabama, and one from Oklahoma - refused to vote for either Kennedy or Nixon. Instead, they cast their votes for Senator Harry Byrd, Sr. of Virginia, a conservative Democrat, even though Byrd had not been a candidate for President. Kennedy carried 12 states by three percentage points or less, while Nixon won six states by the same margin. Kennedy carried all but three states in the populous Northeastern US, and he also carried the large states of Michigan, Illinois, and Missouri in the Midwest. With Lyndon Johnson's help, he also carried most of the South, including the large states of North Carolina, Georgia, and Texas. Nixon carried all but three of the Western states (including California), and he ran strong in the farm belt states, where his biggest victory was Ohio. The New York Times, summarizing the discussion late in November, spoke of a “narrow consensus” among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost as a result of his Catholicism,[16] as Northern Catholics flocked to Kennedy because of attacks on his religion. Interviewing people who voted in both 1956 and 1960, a University of Michigan team analyzing the election returns discovered that people who voted Democratic in 1956 split 33–6 for Kennedy, while the Republican voters of 1956 split 44–17 for Nixon. That is, Nixon lost 28% (17/61) of the Eisenhower voters, while Kennedy lost only 15% of the Stevenson voters. The Democrats, in other words, did a better job of holding their 1956 supporters.[17]

Notably, Kennedy was the last candidate to win the presidency without carrying Ohio and was the only non-incumbent in the 20th century to do so. He is also one of two Democrats to date to win without winning Florida since its start of statehood. Bill Clinton is the other one, having lost Florida in 1992, although he won it in his re-election in 1996. Richard Nixon was the first person to lose a presidential election but carry more than half the states, winning 26 states. The only other person was Gerald Ford in 1976, who won in 27 states.

Kennedy said that he saw the challenges ahead and needed the countries support to get through them. "To all Americans I say that the next four years are going to be difficult and challenging years for us all that a supreme national effort will be needed to move this country safely through the 1960s. I ask your help and I can assure you that every degree of my spirit that I possess will be devoted to the long range interest of the United States and to the cause of freedom around the world."[18]

Kennedy was both the last Northern Democrat and sitting United States senator to win the presidency until the election of Barack Obama of Illinois on November 4, 2008.

Controversies

Many Republicans (including Nixon and Eisenhower) believed that Kennedy had benefited from vote fraud, especially in Texas, of which Lyndon Johnson was Senator, and Illinois, home of Mayor Richard Daley's powerful Chicago political machine.[15] These two states are important because if Nixon had carried both, he would have won the election in the electoral college. Republican Senators such as Everett Dirksen and Barry Goldwater also believed that vote fraud played a role in the election,[1] and they believed that Nixon actually won the national popular vote. Republicans tried and failed to overturn the results in both these states at the time—as well as in nine other states. David Greenberg wrote in Slate, "The thought that Nixon was cheated out of presidency in 1960 has almost become an accepted fact."[19] Some journalists also later claimed that mobster Sam Giancana and his Chicago crime syndicate played a role in Kennedy’s victory in Illinois.[19]

Nixon's campaign staff urged him to pursue recounts and challenge the validity of Kennedy's victory in several states, especially in Illinois, Missouri and New Jersey, where large majorities in Catholic precincts handed Kennedy the election.[1] However, Nixon gave a speech three days after the election stating that he would not contest the election.[1] The Republican National Chairman, Senator Thruston Morton of Kentucky, visited Key Biscayne, Florida, where Nixon had taken his family for a vacation, and pushed for a recount.[1] Morton did challenge the results in 11 states,[15] keeping challenges in the courts into the summer of 1961. However, the only result of these challenges was the loss of Hawaii to Kennedy on a recount.

Kennedy won Illinois by less than 9,000 votes out of 4.75 million cast, or a margin of two-tenths of one percent. [15] However, Nixon carried 92 of the state's 101 counties, and Kennedy's victory in Illinois came from the city of Chicago, where Mayor Richard J. Daley held back much of Chicago's vote until the late morning hours of November 9. The efforts of Daley and the powerful Chicago Democratic organization gave Kennedy an extraordinary Cook County victory margin of 450,000 votes—more than 10% of Chicago's 1960 population of 3.55 million[20]—thus barely overcoming the heavy Republican vote in the rest of Illinois. Earl Mazo, a reporter for the pro-Nixon New York Herald Tribune, investigated the voting in Chicago and claimed to have discovered sufficient evidence of vote fraud to prove that the state was stolen for Kennedy.[15]

In Texas, Kennedy defeated Nixon by a narrow 51% to 49% margin, or 46,000 votes.[15] Some Republicans argued that Johnson's formidable political machine had stolen enough votes in counties along the Mexican border to give Kennedy the victory. Kennedy's defenders, such as his speechwriter and special assistant Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., have argued that Kennedy's margin in Texas (46,000 votes) was simply too large for vote fraud to have been a decisive factor, although cases of voter fraud were discovered there. For example, Fannin County had only 4,895 registered voters, yet 6,138 votes were cast in that county, three-quarters for Kennedy.[1] In an Angelina County precinct, Kennedy received a higher number of votes than the total number of registered voters in the precinct.[1] When Republicans demanded a statewide recount, they learned that the state Board of Elections, whose members were all Democrats, had already certified Kennedy as the official winner in Texas.[1]

In Illinois, Schlesinger and others have pointed out that, even if Nixon carried Illinois, the state alone would not have given him the victory, as Kennedy would still have won 276 electoral votes to Nixon's 246 (with 269 needed to win). More to the point, Illinois was the site of the most extensive challenge process, which fell short despite repeated efforts spearheaded by Cook County state's attorney, Benjamin Adamowski, a Republican, who also lost his re-election bid. Despite demonstrating net errors favoring both Nixon and Adamowski (some precincts—40% in Nixon's case—showed errors favoring them, a factor suggesting error, rather than fraud), the totals found fell short of reversing the results for either candidate. While a Daley-connected circuit judge, Thomas Kluczynski, (who would later be appointed a federal judge by Kennedy, at Daley's recommendation) threw out a federal lawsuit filed to contend the voting totals,[1] the Republican-dominated State Board of Elections unanimously rejected the challenge to the results. Furthermore, there were signs of possible irregularities in downstate areas controlled by Republicans, which Democrats never seriously pressed, since the Republican challenges went nowhere.[21] More than a month after the election, the Republican National Committee abandoned its Illinois voter fraud claims.[15]

However, a special prosecutor assigned to the case brought charges against 650 people, which did not result in convictions.[1] Three Chicago election workers were convicted of voter fraud in 1962 and served short terms in jail.[1] Mazo, the Herald-Tribune reporter, later said that he found names of the dead who had voted in Chicago, along with 56 people from one house.[1] He found cases of Republican voter fraud in southern Illinois, but said the totals didn't match the Chicago fraud he found.[1] After Mazo had published four parts of an intended 12-part voter fraud series documenting his findings which was re-published nationally, he says Nixon requested his publisher stop the rest of the series so as to prevent a constitutional crisis.[1] Nevertheless, the Chicago Tribune wrote that "the election of November 8 was characterized by such gross and palpable fraud as to justify the conclusion that [Nixon] was deprived of victory."[1] Had Nixon won both states, he would have ended up with exactly 270 electoral votes and the presidency, with or without a victory in the popular vote.

Alabama popular vote

The actual number of popular votes received by Kennedy in Alabama is difficult to determine because of the unusual situation in that state. The first minor issue is that, instead of having the voters choose from slates of electors, the Alabama ballot had voters choose the electors individually. Traditionally, in such a situation, a given candidate is assigned the popular vote of the elector who received the most votes. For instance, candidates pledged to Nixon received anywhere from 230,951 votes (for George Witcher) to 237,981 votes (for Cecil Durham); Nixon is therefore assigned 237,981 popular votes from Alabama.

The more important issue is that the statewide Democratic primary had chosen eleven candidates for the Electoral College, five of whom were pledged to vote for Kennedy, and six of whom were free to vote for anyone they chose. All of these candidates won in the general election, and the six unpledged electors voted against Kennedy. The actual number of popular votes received by Kennedy is therefore difficult to allocate. Traditionally, Kennedy is assigned either 318,303 votes (the votes won by the most popular Kennedy elector) or 324,050 votes (the votes won by the most popular Democratic elector); indeed, the results table below is based on Kennedy winning 318,303 votes in Alabama.

Even taking the Alabama totals alone and the vote counts for the other 49 states, Nixon has a 58,181-vote plurality, edging out Kennedy 34,108,157 votes to 34,049,976. Using this calculation without even taking into consideration the alleged occurrences of vote fraud, the 1960 popular vote was even closer than previously thought.[22]

Georgia popular vote

The actual number of popular votes received by Kennedy and Nixon in Georgia is also difficult to determine because voters voted for 12 separate electors. The vote totals of 458,638 votes for Kennedy and 274,472 votes for Nixon reflect the number of votes for the Kennedy and Nixon electors who received the highest number of votes. However, the Republican and Democratic electors receiving the highest number of votes were outliers from the other 11 electors from their party. The average vote totals for the 12 electors were 455,629 votes for the Democratic electors and 273,110 votes for the Republican electors. This shrinks Kennedy's election margin in Georgia by 1,647 votes to 182,519.[23]

Unpledged Democratic electors

Many Democrats were opposed to the national Democratic Party's platform on supporting civil rights and voting rights for African-Americans living in the South. Both before and after the convention, they attempted to put unpledged Democratic electors on their states' ballots in the hopes of influencing the race: the existence of such electors might influence which candidate would be chosen by the national convention, and, in a close race, such electors might be in a position to extract concessions from either the Democratic or Republican presidential candidates in return for their electoral votes.

Most of these attempts failed. Alabama put up a mixed slate of five loyal electors and six unpledged electors. Mississippi put up two distinct slates, one of loyalists and one of unpledged electors. Louisiana also put up two distinct slates, although the unpledged slate did not receive the “Democratic” label. Georgia freed its Democratic electors from pledges to vote for Kennedy, but popular Governor Ernest Vandiver, a candidate for elector himself, publicly backed Kennedy.

In total, fourteen unpledged Democratic electors won election from the voters. Because electors pledged to Kennedy had won a clear majority of the Electoral College, the unpledged electors could not influence the results. Nonetheless, they refused to vote for Kennedy. Instead they voted for Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd, a segregationist Democrat, even though Byrd was not an announced candidate and did not seek their votes. Byrd also received 1 electoral vote from a faithless Oklahoma elector, for a total of 15 electoral votes.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| John Fitzgerald Kennedy | Democratic | Massachusetts | 34,220,984(a) | 49.7% | 303 | Lyndon Baines Johnson | Texas | 303 |

| Richard Milhous Nixon | Republican | California | 34,108,157 | 49.6% | 219 | Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. | Massachusetts | 219 |

| Harry Flood Byrd | (none) | Virginia | —(b) | —(b) | 15 | James Strom Thurmond | South Carolina | 14 |

| Barry Morris Goldwater(c) | Arizona | 1(c) | ||||||

| (unpledged electors) | Democratic | (n/a) | 286,359 | 0.4% | —(d) | (n/a) | (n/a) | —(d) |

| Orval Faubus | States' Rights | Arkansas | 44,984 | 0.1% | 0 | John G. Crommelin | Alabama | 0 |

| Charles Sullivan | Constitution | Mississippi | (TX) 18,162 | 0.0% | 0 | Merritt Curtis | California | 0 |

| Other | 216,982 | 0.3% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 68,895,628 | 100% | 537 | 537 | ||||

| Needed to win | 269 | 269 | ||||||

There were 537 electoral votes, up from 531 in 1956, because of the addition of 2 U.S. Senators and 1 U.S. Representative from each of the new states of Alaska and Hawaii. (The House of Representatives was temporarily expanded from 435 members to 437 to accommodate this, and would go back to 435 when reapportioned according to the 1960 census.)

Source (Popular Vote):Leip, David. "1960 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 7, 2008.Note: Sullivan / Curtis ran only in Texas. In Washington, Constitution Party ran Curtis for President and B. N. Miller for vice-president, receiving 1,401 votes.

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 2, 2005.

(a) This figure is problematic; see Alabama popular vote above.

(b) Byrd was not directly on the ballot. Instead, his electoral votes came from unpledged Democratic electors and a faithless elector.

(c) Oklahoma faithless elector Henry D. Irwin, though pledged to vote for Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., instead voted for non-candidate Harry F. Byrd. However, unlike other electors who voted for Byrd and Strom Thurmond as Vice President, Irwin voted for Barry Goldwater as Vice President.

(d) In Mississippi, the slate of unpledged Democratic electors won. They cast their 8 votes for Byrd and Thurmond.

Close states

- Hawaii, 0.06%

- Illinois, 0.19%

- Missouri, 0.52%

- California, 0.55%

- New Jersey, 0.80%

- New Mexico, 0.74%

- Minnesota, 1.43%

- Delaware, 1.64%

- Alaska, 1.88%

- Texas, 2.00%

- Michigan, 2.01%

- Nevada, 2.32%

- Pennsylvania, 2.32%

- Washington, 2.41%

- South Carolina, 2.48%

- Montana, 2.50%

- Mississippi, 2.64%

- Florida, 3.03%

- Wisconsin, 3.72%

- North Carolina, 4.22%

- New York, 5.26%

- Oregon, 5.24%

- Virginia, 5.47%

- West Virginia, 5.47%

- Ohio, 6.57%

- New Hampshire, 6.84%

- Arkansas, 7.13%

- Tennessee, 7.14%

- Kentucky, 7.18%

- Maryland, 7.23%

- Connecticut, 7.46%

- Idaho, 7.57%

- Utah, 9.64%

- Colorado, 9.73%

See also

- Canada and the 1960 United States presidential election

- History of the United States (1945–1964)

- United States Senate election, 1960

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Another Race To the Finish". The Washington Post. 2000-11-17. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Monday, Jul. 06, 1959 (Monday, Jul. 06, 1959). "THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNORS In 1960 Their Big Year - TIME". Time.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ New York Times

- ^ Humphrey, Hubert H. (1992). The Education of a Public Man, p. 152. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816618976.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Event - Kennedy-Humphrey Primary Debate - May 4, 1960". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Another Race To the Finish". The News & Observer. 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mclellan, Dennis (July 2 2008). "Clay Felker, 82; editor of New York magazine led New Journalism charge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ E. Thomas Wood, "Nashville now and then: Nixon paints the town red". 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

{{cite news}}: Text "NashvillePost.com" ignored (help) - ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1991). Eisenhower: Soldier and President, p. 525. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671747584.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Event - First Kennedy-Nixon Debate - Sep 26, 1960". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Event - Second Kennedy-Nixon Debate - Oct 07, 1960". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Event - Third Kennedy-Nixon Debate - Oct 13, 1960". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Event - Fourth Kennedy-Nixon Debate - Oct 21, 1960". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (2002-06-18). "Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association". American Rhetoric. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The fallacy of Nixon's graceful exit". Salon. 2000-11-10. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ New York Times, November 20, 1960, Section 4, p. E5

- ^ Campbell, Angus (1966). Elections and the Political Order. p. 83.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ UPI.com, Year in Review, http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1960/Kennedy-Wins-1960-Presidential-Election/12295509435928-8/

- ^ a b Greenberg, David (October 16), "Was Nixon Robbed?", Slate

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ Slate, October 16, 2000, "Was Nixon Robbed? The legend of the stolen 1960 presidential election" by David Greenberg

- ^ "The Wall Street Journal Online - John Fund on the Trail". Opinionjournal.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ Gaines, Brian J. (2001). "Popular Myths About Popular Vote–Electoral College Splits" (PDF). PS: Political Science & Politics: 74.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Alexander, Herbert E. (1962). Financing the 1960 Election.

- Campbell, Angus; et al. (1966). Elections and the Political Order, statistical studies of poll data

- Dallek, Robert Gold (1991). "Chapter 16: The Making of a Vice President". Lone Star Rising: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1908–1960.

- Divine, Robert A. Foreign Policy and U.S. Presidential Elections, 1952-1960 1974.

- Fuchs, Lawrence H. (1967). John F. Kennedy and American Catholicism.

- Gallup, George H., ed. The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935-1971. 3 vols. Random House, 1972. press releases

- Ingle, H. Larry, "Billy Graham: The Evangelical in Politics, 1960s-Style," in Peter Bien and Chuck Fager, In Stillness there is Fullness: A Peacemaker's Harvest, Kimo Press.

- Kallina, Edmund F. (1988). Courthouse Over White House: Chicago and the Presidential Election of 1960.

- Kraus, Sidney (1977). The Great Debates: Kennedy vs. Nixon, 1960.

- Lisle, T. David (1988). "Southern Baptists and the Issue of Catholic Autonomy in the 1960 Presidential Campaign". In Paul Harper and Joann P. Krieg, ed. (ed.). John F. Kennedy: The Promise Revisited. pp. 273–285.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Nixon, Richard M. (1978). RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon.

- White, Theodore H. (1961). The Making of the President, 1960.

External links

- 1960 popular vote by counties

- 1960 popular vote by states

- 1960 popular vote by states (with bar graphs)

- Gallery of 1960 Election Posters/Buttons

- How close was the 1960 election? - Michael Sheppard, Michigan State University