Music of Japan: Difference between revisions

Reverted 1 edit by 86.24.190.60; Unconstructive. (TW) |

|||

| Line 218: | Line 218: | ||

* [http://www.hearjapan.com HearJapan - The largest international digital music store for Japanese music] |

* [http://www.hearjapan.com HearJapan - The largest international digital music store for Japanese music] |

||

{{Music of Asia}} |

{{Music of Asia}} |

||

* [http://musicjapanplus.jp Musicjapanplus - The Official Jmusic Web Magazine] |

|||

[[Category:Japanese music]] |

[[Category:Japanese music]] |

||

Revision as of 06:47, 28 January 2010

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

The modern Japanese music scene includes a wide array of performers in distinct styles both traditional and modern. The word for music in Japanese is 音楽 (ongaku), combining the kanji 音 ("on" sound) with the kanji 楽 ("gaku" fun, comfort).[1] Local music often appears at karaoke venues, which is on lease from the record labels.

Traditional Japanese music has no specific beat[clarification needed], and is calm. The music is improvised most of the time. In 1873, a British traveler claimed that Japanese music, "exasperate[s] beyond all endurance the European breast."[2]

Traditional and folk music

Traditional music

Two of the oldest forms of traditional Japanese music are shōmyō, Buddhist chanting, and gagaku, orchestral court music, both of which date to the Nara and Heian periods.[citation needed]

Gagaku is a type of classical music that has been performed at the Imperial court since the Heian period[citation needed]. Kagurauta (神楽歌), Azumaasobi(東遊) and Yamatouta (大和歌) are relatively indigenous repertories. Tōgaku (唐楽) and komagaku originated from the Chinese Tang dynasty via the Korean peninsula[citation needed]. In addition, gagaku is divided into kangen (管弦) (instrumental music) and bugaku (舞楽) (dance accompanied by gagaku).

Originating as early as the 19th century are honkyoku ("original pieces"). These are single (solo) shakuhachi pieces played by mendicant Fuke sect priests of Zen buddhism[citation needed]. These priests, called komusō ("emptiness monk"), played honkyoku for alms and enlightenment. The Fuke sect ceased to exist in the 19th century, but a verbal and written lineage of many honkyoku continues today, though this music is now often practiced in a concert or performance setting.[citation needed]

The samurai often listened to and performed in these musical activities, in their practices of enriching their lives and understanding[citation needed].

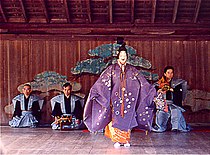

Musical theater also developed in Japan from an early age. Noh (能) or nō arose out of various more popular traditions and by the 14th century had developed into a highly refined art. It was brought to its peak by Kan'ami (1333-1384) and Zeami (1363?-1443). In particular Zeami provided the core of the Noh repertory and authored many treatises on the secrets of the Noh tradition (until the modern era these were not widely read).

Another form of Japanese theater is the puppet theater, often known as bunraku (文楽). This traditional puppet theater also has roots in popular traditions and flourished especially during Chonin in the Edo period (1600-1868)[citation needed]. It is usually accompanied by recitation (various styles of jōruri) accompanied by shamisen music.

During the Edo period actors (after 1652 only male adults) performed the lively and popular kabuki theater. Kabuki, which could feature anything from historical plays to dance plays, was often accompanied by nagauta style of singing and shamisen performance.[citation needed]

Folk music

Biwa hōshi, Heike biwa, mōsō, and goze

The biwa, a form of short-necked lute, was played by a group of itinerant performers (biwa hōshi) who used it to accompany stories.[citation needed] The most famous of these stories is The Tale of the Heike, a 12th century history of the triumph of the Minamoto clan over the Taira[citation needed]. Biwa hōshi began to organize themselves into a guild-like association (tōdō) for visually impaired men as early as the thirteenth century. This guild eventually controlled a large portion of the musical culture of Japan.[citation needed]

In addition, numerous smaller groups of itinerant blind musicians were formed especially in the Kyushu area[citation needed]. These musicians, known as mōsō (blind monk) toured their local areas and performed a variety of religious and semi-religious texts to purify households and bring about good health and good luck. They also maintained a repertory of secular genres. The biwa that they played was considerably smaller than the Heike biwa played by the biwa hōshi.[citation needed]

Lafcadio Hearn related in his book Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things "Mimi-nashi Hoichi" (Hoichi the Earless), a Japanese ghost story about a blind biwa hōshi who performs "The Tale of the Heike"

Blind women, known as goze, also toured the land since the medieval era, singing songs and playing accompanying music on a lap drum.[citation needed] From the seventeenth century they often played the koto or the shamisen. Goze organizations sprung up throughout the land, and existed until recently in what is today Niigata prefecture.[citation needed]

Taiko

The taiko is a Japanese drum that comes in various sizes and is used to play a variety of musical genres.[citation needed] It has become particularly popular in recent years as the central instrument of percussion ensembles whose repertory is based on a variety of folk and festival music of the past. Such taiko music is played by large drum ensembles called kumi-daiko. Its origins are uncertain, but can be sketched out as far back as the 6th and 7th centuries, when a clay figure of a drummer indicates its existence. China influences followed, but the instrument and its music remained uniquely Japanese.[3] Taiko drums during this period were used during battle to intimidate the enemy and to communicate commands. Taiko continue to be used in the religious music of Buddhism and Shintō. In the past players were holy men, who played only at special occasions and in small groups, but in time secular men (rarely women) also played the taiko in semi-religious festivals such as the bon dance.

Modern ensemble taiko is said to have been invented by Daihachi Oguchi in 1951[citation needed]. A jazz drummer, Oguchi incorporated his musical background into large ensembles, which he had also designed. His energetic style made his group popular throughout Japan, and made the Hokuriku region a center for taiko music. Musicians to arise from this wave of popularity included Sukeroku Daiko and his bandmate Seido Kobayashi. 1969 saw a group called Za Ondekoza founded by Tagayasu Den; Za Ondekoza gathered together young performers who innovated a new roots revival version of taiko, which was used as a way of life in communal lifestyles. During the 1970s, the Japanese government allocated funds to preserve Japanese culture, and many community taiko groups were formed. Later in the century, taiko groups spread across the world, especially to the United States. The video game Taiko Drum Master is based around taiko. One example of a modern Taiko band is Gocoo.

Min'yō folk music

Japanese folk songs (min'yō) can be grouped and classified in many ways but it is often convenient to think of four main categories: work songs, religious songs (such as sato kagura, a form of Shintoist music), songs used for gatherings such as weddings, funerals, and festivals (matsuri, especially Obon), and children's songs (warabe uta).

In min'yō, singers are typically accompanied by the three-stringed lute known as the shamisen, taiko drums, and a bamboo flute called shakuhachi. Other instruments that could accompany are a transverse flute known as the shinobue, a bell known as kane, a hand drum called the tsuzumi, and/or a 13-stringed zither known as the koto. In Okinawa, the main instrument is the sanshin. These are traditional Japanese instruments, but modern instrumentation, such as electric guitars and synthesizers, is also used in this day and age, when enka singers cover traditional min'yō songs (Enka being a Japanese music genre all its own).

Terms often heard when speaking about min'yō are ondo, bushi, bon uta, and komori uta. An ondo generally describes any folk song with a distinctive swing that may be heard as 2/4 time rhythm (though performers usually do not group beats). The typical folk song heard at Obon festival dances will most likely be an ondo. A fushi is a song with a distinctive melody. Its very name, which is pronounced "bushi" in compounds, means "melody" or "rhythm." The word is rarely used on its own, but is usually prefixed by a term referring to occupation, location, personal name or the like. Bon uta, as the name describes, are songs for Obon, the lantern festival of the dead. Komori uta are children's lullabies. The names of min'yo songs often include descriptive term, usually at the end. For example: Tokyo Ondo, Kushimoto Bushi, Hokkai Bon Uta, and Itsuki no Komoriuta.

Many of these songs include extra stress on certain syllables as well as pitched shouts (kakegoe). Kakegoe are generally shouts of cheer but in min'yō, they are often included as parts of choruses. There are many kakegoe, though they vary from region to region. In Okinawa Min'yō, for example, one will hear the common "ha iya sasa!" In mainland Japan, however, one will be more likely to hear "a yoisho!," "sate!," or "a sore!" Others are "a donto koi!," and "dokoisho!"

Recently a guild-based system known as the iemoto system has been applied to some forms of min'yō; it is called. This system was originally developed for transmitting classical genres such as nagauta, shakuhachi, or koto music, but since it proved profitable to teachers and was supported by students who wished to obtain certificates of proficiency and artist's names continues to spread to genres such as min'yō, Tsugaru-jamisen and other forms of music that were traditionally transmitted more informally. Today some min'yō are passed on in such pseudo-family organizations and long apprenticeships are common.

See also Ainu music of north Japan.

Okinawan folk music

Umui, religious songs, shima uta, dance songs, and, especially katcharsee, lively celebratory music, were all popular.

Okinawan folk music varies from mainland Japanese folk music in several ways.

First, Okinawan folk music is often accompanied by the sanshin whereas in mainland Japan, the shamisen accompanies instead. Other Okinawan instruments include the Sanba (which produce a clicking sound similar to that of castanets) and a sharp bird whistle.

Second, tonality. A pentatonic scale, which coincides with the major pentatonic scale of Western musical disciplines, is often heard in min'yō from the main islands of Japan, see minyō scale. In this pentatonic scale the subdominant and leading tone (scale degrees 4 and 7 of the Western major scale) are omitted, resulting in a musical scale with no half-steps between each note. (Do, Re, Mi, So, La in solfeggio, or scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6) Okinawan min'yō, however, is characterized by scales that include the half-steps omitted in the aforementioned pentatonic scale, when analyzed in the Western discipline of music. In fact, the most common scale used in Okinawan min'yō includes scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7,

Traditional instruments

- Biwa (琵琶)

- Fue (笛)

- Hichiriki (篳篥)

- Hocchiku (法竹)

- Hyoshigi (拍子木)

- Kane (鐘)

- Kakko (鞨鼓)

- Kokyū (胡弓)

- Koto (琴)

- Niko (二胡)

- Okawa (AKA Ōtsuzumi) (大鼓)

- Ryūteki (竜笛)

- Sanshin (三線)

- Shakuhachi (bamboo flute) (尺八)

- Shamisen (三味線)

- Shime-Daiko (締太鼓)

- Shinobue (篠笛)

- Shō (笙)

- Suikinkutsu (water zither) (水琴窟)

- Taiko (i.e. Wadaiko)太鼓~和太鼓

- Tsuzumi (鼓) (AKA Kotsuzumi)

Arrival of Western music

Traditional pop music

After the Meiji Restoration introduced Western musical instruction, a bureaucrat named Izawa Shuji compiled songs like "Auld Lang Syne" and commissioned songs using a pentatonic melody.[citation needed] . Western music, especially military marches, soon became popular in Japan.[citation needed] . Two major forms of music that developed during this period were shoka, which was composed to bring western music to schools, and gunka, which are military marches with some Japanese elements..[citation needed]

As Japan moved towards representative democracy in the late 19th century, leaders hired singers to sell copies of songs that aired their messages, since the leaders themselves were usually prohibited from speaking in public. The street performers were called enka-shi.[citation needed] . Also at the end of the 19th century, an Osakan form of streetcorner singing became popular; this was called rōkyoku. This included the first two Japanese stars, Yoshida Naramaru and Tochuken Kumoemon..[citation needed]

Westernized pop music is called kayōkyoku, which is said to have and first appeared in a dramatization of Resurrection by Tolstoy. The song "Kachūsha no Uta", composed by Shinpei Nakayama, was sung by Sumako Matsui in 1914. The song became a hit among enka-shi, and was one of the first major best-selling records in Japan.[citation needed] . Ryūkōka, which adopted Western classical music, made waves across the country in the prewar period..[citation needed] Ichiro Fujiyama became popular in the prewar period, but war songs later became popular when the World War II occurred..[citation needed]

Kayōkyoku became a major industry, especially after the arrival of superstar Misora Hibari.[citation needed] . In the 1950s, tango and other kinds of Latin music, especially Cuban music, became very popular in Japan.[citation needed] . A distinctively Japanese form of tango called dodompa also developed. Kayōkyoku became associated entirely with traditional Japanese structures, while more Western-style music was called Japanese pop.[citation needed] . Enka music, adopting Japanese traditional structures, became quite popular in the postwar period, though its popularity has waned since the 1970s and enjoys little favour with contemporary youth.[citation needed] . Famous enka singers include Hibari Misora, Saburo Kitajima, Ikuzo Yoshi and Kiyoshi Hikawa.

Art music

Western classical music

Western classical music has a strong presence in Japan and the country is one of the most important markets for this music tradition.[citation needed] , with Toru Takemitsu (famous as well for his avant-garde works and movie scoring) being the best known.[citation needed] . Also famous is the conductor Seiji Ozawa. Since 1999 the pianist Fujiko Hemming, who plays Liszt and Chopin, has been famous and her CDs have sold millions of copies.[citation needed] . Japan is also home to the world's leading wind band.[citation needed] , the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra, and the largest music competition of any kind, the All-Japan Band Association national contest.[citation needed] . Japanese, Western classical music does not represent Japan's original culture. Japanese were first exposed to it in the second half of the 19th century, after more than 200 hundred years of national isolation during the Edo Period.[citation needed] . But after that, Japanese studied classical music earnestly to make it a part of their own artistic culture.

Jazz

From the 1930s on (except during World War II, when it was repressed as music of the enemy).[citation needed] , jazz has had a strong presence in Japan.[citation needed] . The country is an important market for the music, and it is common that recordings no longer available in the United States are available in Japan. A number of Japanese jazz musicians have achieved popularity abroad as well as at home..[citation needed] Musicians such as June (born in Japan) and Dan (third generation American born, of Hiroshima fame), and Sadao Watanabe have a large fan base outside their native country.

Lately, club jazz or nu-jazz has become popular with a growing number of young Japanese.[citation needed] . Native DJs such as Ryota Nozaki (Jazztronik), the two brothers Okino Shuya and Okino Yoshihiro of Kyoto Jazz Massive, Toshio Matsuura (former member of the United Future Organization) and DJ Shundai Matsuo creator of the popular monthly DJ event, Creole in Beppu, Japan as well as nu-jazz artists, Sleepwalker, GrooveLine, and Soil & "Pimp" Sessions have brought great change to the traditional notions of jazz in Japan.

Today, some of the newer and very interesting bands include Ego-Wrappin' and Sakerock.

Popular music

Rock music

In the 1960s, Japanese bands imitated The Beatles, Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, along with other Appalachian folk music, psychedelic rock, mod and similar genres; this was called Group Sounds (G.S.). John Lennon of The Beatles later became one of most favourite Western musicians in Japan.[4]

Group Sounds is a genre of Japanese rock music that was popular in the mid to late 1960s.[citation needed] . The Tigers was the most popular G.S. band in the era. Later, some of the members of The Tigers, The Tempters and The Spiders formed the first Japanese supergroup Pyg.

Homegrown Japanese country rock had developed by the late 1960s..[citation needed] Artists like Happy End are considered to have virtually developed the genre. During the 1970s, it grew more popular.[citation needed] . The Okinawan band Champloose, along with Carol, RC Succession and Shinji Harada were especially famous and helped define the genre's sound.

In the 1980s, the Boøwy inspired alternative rock bands like Shonen Knife, Boredoms, The Pillows and Tama & Little Creatures as well as more mainstream bands as Glay. Most influentially, the 1980s spawned Yellow Magic Orchestra, which was inspired by developing electronic music, led by Haruomi Hosono. In 1980, Huruoma and Ry Cooder, an American musician, collaborated on a rock album with Shoukichi Kina, driving force behind the aforementioned Okinawan band Champloose. They were followed by Sandii & the Sunsetz, who further mixed Japanese and Okinawan influences. Also during the 80's, Japanese rock bands gave birth to the movement known as visual kei, represented during its history by bands like Buck-Tick, X Japan, Luna Sea, Malice Mizer and many others, some of which experienced success in the recent years.

In the 1990s, Japanese rock musicians such as B'z, Mr. Children, Southern All Stars, Tube, T-Bolan, Wands, Field of View, Deen, Ulfuls, Lindberg, Sharam Q, Spitz, Judy and Mary, The Yellow Monkey, The Brilliant Green and Dragon Ash achieved great commercial success.[citation needed] , some of them establishing marks in Japanese music history.[citation needed] . B'z is the #1 best selling act in Japanese music since Oricon started to count.[citation needed] , followed by Mr. Children.[citation needed] . In 1990s, J-pop songs were often used in films, anime, television advertisement and dramatic programming, becoming some of the best-selling forms of music in Japan.[citation needed] . The rise of disposable pop has been linked with the popularity of karaoke, leading to much criticism that it is consumerist and shallow.[citation needed] . For example, Kazufumi Miyazawa of The Boom, claims "I hate that buy, listen, and throw away and sing at a karaoke bar mentality."

Glay, Shazna, Dir en grey, Janne Da Arc, Luna Sea, and L'Arc-en-Ciel, which are often considered visual kei or related to this genre, also achieved great commercial success in the late 1990s.[citation needed] . Around 1998, Glay was arguably the most massively popular band.[5] In 1999 the band played for a crowd of 200,000, the most attended single concert ever held in Japan.[6] Gackt Camui (ex Malice Mizer) even without exact music genre is known as both visual rock and pop star, having official fanbase Dears in Japan, while in 2009 opened in Taiwan and Korea, with looking for expanding of it around Asia and overseas.

The first Fuji Rock Festival opened in 1997. Rising Sun Rock Festival opened in 1999. Summer Sonic Festival and Rock in Japan Festival opened in 2000. Though the rock scene in the 2000s is not as strong, newer bands such as Bump of Chicken, Sambomaster, Orange Range, Remioromen, Uverworld, Radwimps and Aqua Timez, which are considered rock bands, have achieved success. Orange Range also adopts[clarification needed] hip hop. Established bands as Glay, L'Arc-en-Ciel, B'z and Mr. Children, also continue to top charts, though B'z and Mr. Children are the only bands to maintain a high standards of their sales along the years.

Japanese rock has a vibrant underground rock scene,[citation needed] best known internationally for noise rock bands such as Boredoms and Melt Banana, as well as stoner rock bands such as Boris and alternative acts such as Shonen Knife (who were championed in the West by musicians such as Kurt Cobain), Pizzicato Five and The Pillows (who gained massive international attention in 1999 for soundtracking the anime FLCL). More conventional indie rock artists such as Eastern Youth, The Band Apart and Number Girl have found some mainstream success in Japan.[citation needed] , but relatively little recognition outside of their home country.

Punk rock / alternative

Early examples of punk rock / no wave in Japan include The SS, The Star Club, The Stalin, INU, Gaseneta, Lizard (who were produced by the Stranglers) and Friction (whose guitarist Reck had previously played with Teenage Jesus and the Jerks before returning to Tokyo) and The Blue Hearts. The early punk scene was immortalised on film by Sogo Ishii, who directed the 1982 film Burst City featuring a cast of punk bands/musicians and also filmed videos for The Stalin. In the 80s, hardcore bands such as GISM, Gauze, Confuse, Lip Cream and Systematic Death began appearing, some incorporating crossover elements.[citation needed] . The independent scene also included a diverse number of alternative / post-punk / new wave artists such as Aburadako, P-Model, Uchoten, Auto-Mod, Buck-Tick, Guernica and Yapoos (both of which featured Jun Togawa), G-Schmitt, Totsuzen Danball and Jagatara, along with noise/industrial bands such as Hijokaidan and Hanatarashi.

Heavy metal

Japan is known for being a successful area for metal bands touring around the world and many live albums are recorded in Japan. Notable examples are Judas Priest's Unleashed in the East, Iron Maiden's Maiden Japan and Deep Purple's Made in Japan.

The most popular genres of metal in Japan are Neo-classical metal and Power metal.[citation needed] . Bands such as Angra, Sonata Arctica and Skylark have had major success in Japan.[citation needed] . Japanese Neo-classical bands also had success among international Neo-classical fans with Concerto Moon and Ark Storm being the leading bands.[citation needed] .

Speed metal, Melodic death metal and Doom metal also have followings.[citation needed] . Many older Japanese metal bands (1980's to 1990's) are speed metal due to the success of X Japan.[citation needed] . Extreme metal is usually treated as an underground form of music in Japan.[citation needed] . Notable acts are Sabbat and Sigh.

Loudness is the most successful Japanese heavy metal band outside of Japan.[citation needed] . Their 6th album, Lightning Strikes peaked at #64 on the Billboard 200.

Western folk music

After the boom of Group Sounds, there were group of people who sang their songs using only guitar.[citation needed] . Nobuyasu Okabayashi was the first who became widely recognized.[citation needed] . Wataru Takada who got ideas from Woody Guthrie also became popular.[citation needed] . The two were influenced by American folk music and made lyrics in Japanese. Takada brought Japanese modern poetry into lyrics and Kazuki Tomokawa made an album using only Chuya Nakahara's poems for them. Tomobe Masato who was inspired by Bob Dylan wrote the lyrics on his own and became considered a poet.[citation needed] .

Electropop and club music

Electronic pop music in Japan became a successful commodity with the "Technopop" craze of the late 70s and 80s.[citation needed] , beginning with Yellow Magic Orchestra and solo albums of Ryuichi Sakamoto and Haruomi Hosono in 1978 before hitting popularity in 79/80. Influenced by disco, impressionistic and 20th century classical composition, jazz/fusion pop, new wave and technopop artists such as Kraftwerk and Telex, these artists were commercial yet uncompromising.[citation needed] ; Ryuichi Sakamoto claims that "to me, making pop music is not a compromise because I enjoy doing it". The artists that fall under the banner of technopop in Japan are as loose as those that do so in the West, thus new wave bands such as P-Model and The Plastics fall under the category alongside the symphonic techno arrangements of Yellow Magic Orchestra. The popularity of this music meant that many popular artists of the 70s that previously were known for acoustic music turned to techno production,.[citation needed] such as Taeko Onuki and Akiko Yano, and idol producers began employing electronic arrangements for new singers in the 80s.[citation needed] . Today, newer artists such as Polysics pay explicit homage to this era of Japanese popular (and in some cases underground or difficult to obtain) music..[citation needed]

Dance and disco music

In 1984, American musician Michael Jackson's album Thriller became the first album by a Western artist to sell over one million copies in Japanese Oricon charts history.[7] His style is cited as one of the models for Japanese dance music, leading the popularity of Avex Group and Johnny & Associates.[8]

In 1990, Avex Trax began to release the Super Eurobeat series in Japan. Eurobeat in Japan led the popularity of group dance form Para Para. While Avex's artists such as Every Little Thing and Ayumi Hamasaki became popular in 1990s, new names in tha late 90s included Hikaru Utada and Morning Musume. Hikaru Utada's debut album, "First Love", went on to be the highest-selling album in Japan with over 7 million copies sold, whereas Ayumi Hamasaki became Japan's top selling female and solo artist, and Morning Musume remains one of the most well-known girl groups in the Japanese pop music industry.

Hip-Hop

Hip-hop is a newer form of music on the Japanese music scene. Many felt it was a trend that would immediately pass. However, the genre has lasted for many years and is still thriving. In fact, rappers in Japan did not achieve the success of hip-hop artists in other countries until the late 1980s. This was mainly due to the music world's belief that "Japanese sentences were not capable of forming the rhyming effect that was contained in American rappers' songs."[9] There is a certain, well-defined structure to the music industry called "The Pyramid Structure of a Music Scene". As Ian Condry notes, "viewing a music scene in terms of a pyramid provides a more nuanced understanding of how to interpret the significance of different levels and kinds of success."[10] The levels are as follows (from lowest to highest): fans and potential artists, performing artists, recording artists (indies), major label artists, and mega-hit stars. These different levels can be clearly seen at a genba, or nightclub. Different "families" of rappers perform on stage. A family is essentially a collection of rap groups that are usually headed by one of the more famous Tokyo acts, which also include a number of proteges.[11] They are important because they are "the key to understanding stylistic differences between groups."[12] Hip-hop fans in the audience are the ones in control of the night club. They are the judges who determine the winners in rap battles on stage. An example of this can be seen with the battle between rap artists Dabo (a major label artist) and Kan (an indie artist). Kan challenged Dabo to a battle on stage while Dabo was mid-performance. Another important part of night clubs was displayed at this time. It showed "the openness of the scene and the fluidity of boundaries in clubs."[13] Both artists did a cappella freestyle, but in the end, the audience showed their approval for Dabo.

Roots music

In the late 1980s, roots bands like Shang Shang Typhoon and The Boom became popular. Okinawan roots bands like Nenes and Kina were also commercially and critically successful. This led to the second wave of Okinawan music, led by the sudden success of Rinkenband. A new wave of bands followed, including the comebacks of Champluse and Kina, as led by Kikusuimaru Kawachiya; very similar to kawachi ondo is Tadamaru Sakuragawa's goshu ondo.

Latin, reggae and ska music

Other forms of music from Indonesia, Jamaica and elsewhere were assimilated. African soukous and Latin music was popular as was Jamaican reggae and ska, exemplified by Mice Teeth, Mute Beat, La-ppisch, Home Grown and Ska Flames, Determinations, and Tokyo Ska Paradise Orchestra.

Noise music

Another recognized music form, from Japan is noise music. The noise from this country is called Japanoise.

Theme music

Theme music composed for films, anime, Tokusatsu, and Japanese television dramas are considered a separate music genre. Several prominent musical artists and groups have spent most of their musical careers performing theme songs and composing soundtracks for visual media. Such artists include Masato Shimon (current holder of the world record for most successful single in Japan for "Oyoge! Taiyaki-kun")[14], Ichirou Mizuki, all of the members of JAM Project, Akira Kushida, Isao Sasaki, and Mitsuko Horie. Notable composers of Japanese theme music include Michiru Ōshima, Yoko Kanno, Toshihiko Sahashi, Yuki Kajiura and Kōtarō Nakagawa.

Game music

When the first electronic games were sold, they only had rudimentary sound chips with which to produce music. As the technology advanced. the quality of sound and music these game machines could produce increased dramatically. The first game to take credit for its music was Xevious, also noteworthy for its deeply (at that time) constructed stories. Though many games have had beautiful music to accompany their gameplay, one of the most important games in the history of the video game music is Dragon Quest. Kōichi Sugiyama, a composer who was known for his music for various anime and TV shows, including Cyborg 009 and a feature film of Godzilla vs. Biollante, got involved in the project out of the pure curiosity and proved that games can have serious soundtracks. Until his involvement, music and sounds were often neglected in the development of video games and programmers with little musical knowledge were forced to write the soundtracks as well. Undaunted by technological limits, Sugiyama worked with only 8 part polyphony to create a soundtrack that would not tire the player despite hours and hours of gameplay.

Another well-known author of video game music is Nobuo Uematsu of Mistwalker. Even Uematsu's earlier compositions for the game series, Final Fantasy, on Famicom (Nintendo Entertainment System in America) are being arranged for full orchestral score. In 2003, he even took his rock-based tunes from their original MIDI format and created The Black Mages.

Yasunori Mitsuda is a highly known composer of such games as Xenogears, Xenosaga Episode I, Chrono Cross, and Chrono Trigger.

Koji Kondo, the main composer for Nintendo, is also prominent on the Japanese game music scene. He is best-known for the Zelda and Mario themes.

The techno/trance music production group I've Sound has made a name for themselves first by making themes for eroge computer games, and then by breaking into the anime scene by composing themes for them. Unlike others, this group was able to find fans in other parts of the world through their eroge and anime themes.

Today, game soundtracks are sold on CD. Famous singers like Hikaru Utada sometimes sing songs for games as well, and this is also seen as a way for singers to make a names for themselves.

References

- ^ Clewley, pg. 143

- ^ "News World news Germany Lost in translation"

- ^ History of Taiko [1] "鼓と太鼓のながれ" - 中国の唐からわが国に入ってきたいろんな太鼓が、時代と共にどのように変遷してきたかを各種の資料からまとめると、次のようになる。

- ^ "Japan keeps Lennon's memory alive". BBC. 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ "The Day the Phones Died". Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ "Barks" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ Template:Ja icon "【マイケル急死】日本でもアルバム売り上げ1位を獲得". Sankei Shimbun. 2009-06-26. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ^ Template:Ja icon "さよならポップス界のピーターパン 栄光と奇行と". Asahi Shimbun. 2009-06-26. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ^ Kinney, Caleb. "Hip-hop influences Japanese Culture. http://www.lightonline.org/articles/chiphopjapan.html

- ^ Condry, Ian. "Hip-Hop Japan". Durham and London, Duke University Press, 102.

- ^ Condry, Ian. "A History of Japanese Hip-Hop: Street Dance, Club Scene, Pop Market." In Global Noise: Rap and Hip-Hop Outside the USA, 237, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

- ^ Condry, Ian . "A History of Japanese Hip-Hop: Street Dance, Club Scene, Pop Market." In Global Noise: Rap and Hip-Hop Outside the USA, 237. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

- ^ Condry, Ian. "Hip-Hop Japan". Durham and London, Duke University Press, 144.

- ^ "「およげ!たいやきくん」がギネス認定、再評価の気運高まる". Oricon. 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

See also

- All-Japan Band Association

- Buddhist music

- Chindonya

- Group Sounds

- Japanese hardcore

- Japanese hip hop

- Japanoise

- J-pop

- Seiyuu

- Shibuya-kei

- Shintō music

- SILENZIOSA LUNA - 沈黙の月

- Visual kei

- Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra

- List of Japanese rock bands

- List of Japanese hip hop musicians

- List of J-pop artists

- In scale