Military history of Iran: Difference between revisions

Woohookitty (talk | contribs) m WPCleaner (v1.09) Repaired link to disambiguation page - (You can help) - Qajar |

→Buwayhid dynasty (934 to 1055): Fixed links to Encyclopædia Iranica articles & General fixes using AWB (7910) |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

==Buwayhid dynasty (934 to 1055)== |

==Buwayhid dynasty (934 to 1055)== |

||

{{main|Buwayhids}} |

{{main|Buwayhids}} |

||

The Buyid dynasty<ref>Busse, Heribert (1975), "Iran Under the Buyids", in Frye, R. N., ''The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs''., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, page 270: "Aleppo remained a buffer between the Buyid empire and Byzantium".</ref> were a [[Shia Islam|Shī‘ah]] [[Persian people|Persian]]<ref>[http://www. |

The Buyid dynasty<ref>Busse, Heribert (1975), "Iran Under the Buyids", in Frye, R. N., ''The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs''., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, page 270: "Aleppo remained a buffer between the Buyid empire and Byzantium".</ref> were a [[Shia Islam|Shī‘ah]] [[Persian people|Persian]]<ref>[http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/buyids]</ref><ref>[http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/deylamites Encyclopedia Iranica: "Deylamites"]</ref> dynasty that originated from [[Daylaman]] in [[Gilan]]. They founded a confederation that controlled most of modern-day [[Iran]] and [[Iraq]] in the 10th and 11th centuries. |

||

==Ghaznavid Empire (963 to 1187)== |

==Ghaznavid Empire (963 to 1187)== |

||

Revision as of 22:24, 15 January 2012

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

With thousands of years of recorded history, and due to an unchanging geographic (and subsequently geopolitical) condition, Iran (previously known as Persia in the West until 1935) has had a long, varied, and checkered military culture and history, ranging from triumphant and unchallenged ancient military supremacy affording effective superpower status in its day, to a series of near catastrophic defeats (beginning with the destruction of Elam) at the hand of previously subdued peripheral nations (including Greece, Arabia, and the Asiatic nomadic tribes at the Eastern boundary of the lands traditionally home to the Iranian people).

Elam

Medes

Achaemenid Era

The Achaemenid Empire (559 BC–330 BC) was the first of the Persian Empires to rule over significant portions of Greater Iran. The empire possessed a “national army” of roughly 120.000-150.000 troops, plus several tens of thousands of troops from their allies.

The Persian army was divided into regiments of a thousand each, called hazarabam. Ten hazarabams formed a haivarabam, or division. The best known haivarabam were the Immortals, the King's personal guard division. The smallest unit was the ten man dathaba. Ten dathabas formed the hundred man sataba.

The royal army used a system of color uniforms to identify different units. A large variety of colors were used, some of the most common being yellow, purple, and blue. But this system was probably limited to native Persian troops and was not used for their numerous allies.

The usual tactic employed by the Persians in the early period of the empire, was to form a shield wall that archers could fire over. These troops (called sparabara, or shield-bearers) were equipped with a large rectangular wicker shield called a spara, and armed with a short spear, measuring around six feet long.

The bow was the most widely used weapon of the Persians. The role of the sparabara was to soften the enemy with volleys of arrows. The main shock action was done by the cavalry. The heavily equipped Persian foot soldiers were not ideal for shock attacks.

Seleucid Empire (330 to 150 BCE)

The Seleucid Empire was a Hellenistic successor state of Alexander the Great's dominion, including central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, Turkmenistan, Pamir and the Indus valley.

Parthian Empire (250 BCE– 226 CE)

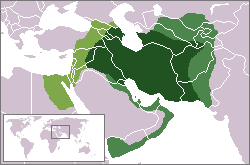

Parthia was an Iranian civilization situated in the northeastern part of modern Iran, but at the height of its power, the Parthian dynasty covered all of Iran proper, as well as regions of the modern countries of Armenia, Iraq, Georgia, eastern Turkey, eastern Syria, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, the Persian Gulf, the coast of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and the UAE.[1]

The Parthian empire was led by the Arsacid dynasty, which reunited and ruled over the Iranian plateau, after defeating and disposing the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, beginning in the late 3rd century BC, and intermittently controlled Mesopotamia between 150 BC and 224 AD. It was the third native dynasty of ancient Iran (after the Median and the Achaemenid dynasties). Parthia was the arch-enemy of the Roman Empire in the east.

After the Scythian-Parni nomads had settled in Parthia and built a small independent kingdom, they rose to power under king Mithridates the Great (171-138 BC).[2] Later, at the height of their power, Parthian influence reached as far as Ubar in Arabia, the nexus of the frankincense trade route, where Parthian-inspired ceramics have been found. The power of the early Parthian empire seems to have been overestimated by some ancient historians, who could not clearly separate the powerful later empire from its more humble obscure origins. The end of this long-lived empire came in 224 AD, when the empire was loosely organized and the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassals, the Persians of the Sassanid dynasty.

Sassanid Era (226 CE to 637 CE)

The birth of the Sassanid army dates back to the rise of Ardashir I (r. 226–241), the founder of the Sassanid dynasty, to the throne. Ardashir aimed at the revival of the Persian Empire, and to further this aim, he reformed the military by forming a standing army which was under his personal command and whose officers were separate from satraps, local princes and nobility. He restored the Achaemenid military organizations, retained the Parthian cavalry model, and employed new types of armour and siege warfare techniques. This was the beginning for a military system which served him and his successors for over 400 years, during which the Sassanid Empire was, along with the Roman Empire and later the East Roman Empire, one of the two superpowers of Late Antiquity in Western Eurasia. The Sassanid army protected Eranshahr ("the realm of Iran") from the East against the incursions of central Asiatic nomads like the Hephthalites, Turks, while in the west it was engaged in a recurrent struggle against the Roman Empire.[citation needed]

Islamic conquest (637 to 651)

The Islamic conquest of Persia (633–656) led to the end of the Sassanid Empire and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. However, the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost, but were to a great extent absorbed by the new Islamic polity.

Most Muslim historians have long offered the idea that Persia, on the verge of the Arab invasion, was a society in decline and decay and thus it embraced the invading Arab armies with open arms. This view is not widely accepted however. Some authors have for example used mostly Arab sources to illustrate that "contrary to the claims , Iranians in fact fought long and hard against the invading Arabs."[3] This view further more holds that once politically conquered, the Persians began engaging in a culture war of resistance and succeeded in forcing their own ways on the victorious Arabs.[4][5]

Tahirid dynasty (821 to 873)

The Tahirid dynasty ruled the northeastern Persian Empire region of Khorasan (parts that are presently in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan). The Tahirid capital was Nishapur[citation needed].

Although nominally subject to the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, the Tahirid rulers were effectively independent. The dynasty was founded by Tahir ibn Husayn, a leading general in the service of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun. Tahir's military victories were rewarded with the gift of lands in the east of Persia, which were subsequently extended by his successors as far as the borders of India.

The Tahirid dynasty is considered to be the first independent dynasty from the Abbasid caliphate established in Khorasan. They were overthrown by the Saffarid dynasty, who annexed Khorasan to their own empire in eastern Persia.

Alavid dynasty (864 to 928)

The Alavids or Alavians were a Shia emirate based in Mazandaran of Iran. They were descendants of the second Shi'a Imam (Imam Hasan ibn Ali) and brought Islam to the south Caspian Sea region of Iran. Their reign was ended when they were defeated by the Samanid empire in 928 AD. After their defeat some of the soldiers and generals of the Alavids joined the Samanid dynasty. Mardavij the son of Ziar was one of the generals that joined the Samanids. He later founded the Ziyarid dynasty. Ali, Hassan and Ahmad the sons of Buye [bu:je] (that were founders of the Buyid or Buwayhid dynasty) were also among generals of the Alavid dynasty who joined the Samanid army.

Saffarid dynasty (861 to 1003)

The Saffarid dynasty ruled a short-lived empire in Sistan, which is a historical region now in southeastern Iran and southwestern Afghanistan. Their rule was between 861 to 1003.[6]

The Saffarid capital was Zaranj (now in Afghanistan). The dynasty was founded by – and took its name from – Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar, a man of humble origins who rose from an obscure beginning as a coppersmith (saffar) to became a warlord. He seized control of the Seistan region, conquering all of Afghanistan, modern-day eastern Iran, and parts of Pakistan. Using their capital (Zaranj) as base for an aggressive expansion eastwards and westwards, they overthrew the Tahirid dynasty and annexed Khorasan in 873. By the time of Ya'qub's death, he had conquered Kabul Valley, Sindh, Tocharistan, Makran (Baluchistan), Kerman, Fars, Khorasan, and nearly reaching Baghdad but then suffered defeat.[7]

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

The Saffarid empire did not last long after Ya'qub's death. His brother and successor Amr bin Laith was defeated in a battle with the Samanids in 900. Amr bin Laith was forced to surrender most of their territories to the new rulers. The Saffarids were subsequently confined to their heartland of Sistan, with their role reduced to that of vassals of the Samanids and their successors.

Samanid dynasty (875 to 999)

The Samanids (819–999)[8] were a Persian dynasty in Central Asia and Greater Khorasan, named after its founder Saman Khuda who converted to Sunni Islam[9] despite being from Zoroastrian theocratic nobility. It was among the first native Iranian dynasties in Greater Iran and Central Asia after the Arab conquest and the collapse of the Sassanid Persian empire.

Ziyarid dynasty (928 to 1043)

The Ziyarids, also spelled Zeyarids (زیاریان or آل زیار), were an Iranian dynasty that ruled in the Caspian sea provinces of Gorgan and Mazandaran from 928-1043 (also known as Tabarestan). The founder of the dynasty was Mardavij (from 927 to 935), who took advantage of a rebellion in the Samanid army of Iran to seize power in northern Iran. He soon expanded his domains and captured the cities of Hamadan and Isfahan.

Buwayhid dynasty (934 to 1055)

The Buyid dynasty[10] were a Shī‘ah Persian[11][12] dynasty that originated from Daylaman in Gilan. They founded a confederation that controlled most of modern-day Iran and Iraq in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Ghaznavid Empire (963 to 1187)

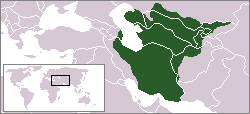

The Ghaznavids were a Muslim dynasty of Turkic slave origin[13] which existed from 975 to 1187 and ruled much of Persia, Transoxania, and the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.[14]

The dynasty was founded by Sebuktigin upon his succession to rule of territories centered around the city of Ghazni from his father-in-law, Alp Tigin, a break-away ex-general of the Samanid sultans.[15] Sebuktigin's son, Shah Mahmoud, expanded the empire in the region that stretched from the Oxus river to the Indus Valley and the Indian Ocean; and in the west it reached Rey and Hamadan. Under the reign of Mas'ud I it experienced major territorial losses. It lost its western territories to the Seljuqs in the Battle of Dandanaqan resulting in a restriction of its holdings to what is now Afghanistan, as well as Balochistan and the Punjab. In 1151, Sultan Bahram Shah lost Ghazni to Ala'uddin Hussain of Ghor and the capital was moved to Lahore until its subsequent capture by the Ghurids in 1186.

Seljuq Empire (1037 to 1187)

The Seljuqs were a Turco-Persian[17][18] Sunni Muslim dynasty that ruled parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to 14th centuries. They set up an empire, the Great Seljuq Empire, which at its height stretched from Anatolia through Persia and which was the target of the First Crusade. The dynasty had its origins in the Turcoman tribal confederations of Central Asia and marked the beginning of Turkic power in the Middle East. After arriving in Persia, the Seljuqs adopted the Persian culture[19] and are regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Western Turks – the present-day inhabitants of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan.

Khwarezmian Empire (1077 to 1231)

The Khwarezmian dynasty, also known as Khwarezmids or Khwarezm Shahs was a Persianate Sunni Muslim dynasty of Tajik origin.[20]

They ruled Greater Iran in the High Middle Ages, in the period of about 1077 to 1231, first as vassals of the Seljuqs[citation needed], Kara-Khitan,[21] and later as independent rulers, up until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. The dynasty was founded by Anush Tigin Gharchai, a former slave of the Seljuq sultans, who was appointed the governor of Khwarezm. His son, Qutb ud-Dīn Muhammad I, became the first hereditary Shah of Khwarezm.[22]

Ilkhanate (1256 to 1353)

The Ilkhanate was a Mongol khanate established in Persia in the 13th century, considered a part of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanate was based, originally, on Genghis Khan's campaigns in the Khwarezmid Empire in 1219–1224, and founded by Genghis's grandson, Hulagu, in what territories which today comprise most of Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and western Pakistan. The Ilkhanate initially embraced many religions, but was particularly sympathetic to Buddhism and Christianity, and sought a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Crusaders in order to conquer Palestine. Later Ilkhanate rulers, beginning with Ghazan in 1295, embraced Islam.

Muzaffarid dynasty (1314 to 1393)

Chupanid dynasty (1337 to 1357)

Jalayerid dynasty (1339 to 1432)

The Jalayirids (آل جلایر) were a Mongol descendant dynasty which ruled over Iraq and western Persia [23] after the breakup of the Mongol Khanate of Persia (or Ilkhanate) in the 1330s.

The Jalayirid sultanate lasted about fifty years, until disrupted by Tamerlane's conquests and the revolts of the "Black sheep Turks" or Kara Koyunlu. After Tamerlane's death in 1405, there was a brief unsuccessful attempt to re-establish the Jalayirid sultanate and Jalayirid sultanate was ended by Kara Koyunlu in 1432.

Timurid Empire (1370 to 1506)

The Timurids were a Central Asian Sunni Muslim dynasty of originally Turko-Mongol descent whose empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran, modern Afghanistan, as well as large parts of Pakistan, India, Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the Caucasus. It was founded by the militant conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) in the 14th century.

In the 16th century, Timurid prince Babur, the ruler of Ferghana, invaded India and founded the Mughal Empire, which ruled most of the Indian subcontinent until its decline after Aurangzeb in the early 18th century, and was formally dissolved by the British Raj after the Indian rebellion of 1857.

Qara Qoyunlu Turcomens (1407 to 1468)

Aq Qoyunlu Turcomans (1378 to 1508)

Safavid Era (1501 to 1736)

The Safavid rulers of Persia, like the Mamluks of Egypt, viewed firearms with distaste, and at first made little attempt to adopt them into their armed forces. Like the Mamluks they were taught the error of their ways by the powerful Ottoman armies. Unlike the Mamluks they lived to apply the lessons they had learnt on the battlefield. In the course of the sixteenth century, but still more in the seventeenth, the shahs of Iran took steps to acquire handguns and artillery pieces and to re-equip their forces with them. Initially, the principal sources of these weapons appears to have been Venice, Portugal, and England.

Despite their initial reluctance, the Persians very rapidly acquired the art of making and using handguns. A Venetian envoy, Vincenzo di Alessandri, in a report presented to the Council of Ten on 24 September 1572, observes:

"They used for arms, swords, lances, arquebuses, which all the soldiers carry and use; their arms are also superior and better tempered than those of any other nation. The barrels of the arquebuses are generally six spans long, and carry a ball little less than three ounces in weight. They use them with such facility that it does not hinder them drawing their bows nor handling their swords, keeping the latter hung at their saddle bows till occasion requires them. The arquebus is then put away behind the back so that one weapon does not impede the use of the other."

This picture of the Persian horseman, equipped for almost simultaneous use of the bow, sword, and firearm, aptly symbolized the dramatic and complexity of the scale of changes that the Persian Military was undergoing. While the use of personal firearms was becoming commonplace, the use of field artillery was limited and remained on the whole ineffective.

In bringing about a 'modern' gunpowder era Persian army it can not be argued that Shah Abbas (1587–1629) was not instrumental. Following the Ottoman Army model that had impressed him in combat the Shah set about to build his new army. He was much helped by two English brothers, Anthony and Robert Sherley, who went to Iran in 1598 with twenty-six followers and remained in the Persian service for a number of years. The brothers helped organize the army into an officer-paid and well-trained standing army similar to a European model. It was organized along three divisions: Ghilman ('crown servants or slaves' usually conscripted from Armenian, Georgian and Circassian lands), Tofongchis (musketeers), and Topchis (artillery-men)

Shah Abbas's new model army was massively successful and allowed him to re-unite parts of Greater Iran and expand his nations territories at a time of great external pressure and conflict. In 1622 Persian artillery managed to conquer the powerful walls of Kandahar, and again in 1649 during the Mughal–Safavid War.

Upon the fall of the Safavid dynasty Persia entered into a period of uncertainty. The previously highly organized military fragmented and the pieces were left for the following dynasties to collect.

Afsharid Dynasty (1750 to 1794)

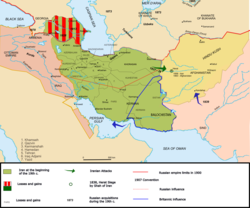

Following the decline of the Safavid state a brilliant general by the name of Nader Shah took the reins of the country. This period and the centuries following it were characterised by the rise in Russian power to Persia's north.

From the time of Peter The Great, the northern states of the Persian Empire were under threat of Russian annexation. In 1710, Tsar Peter formulated his foreign policy principles, the backbone of which was 'invasion and territorial expansion'. The first to suffer from the new Russian power was the Ottoman Empire. However, pressure was soon exerted on the Persian Empire as well. In May 1723, the first major Russo-Persian War occurred and the invasion came as far as the northern city of Rasht. At the Treaty of Bab-e Ali the Ottoman and Russian Empires divided up large portions of Persia between themselves. It was Nader Shah who, with great force[citation needed], drove the Ottomans and Russians[citation needed] out of the occupied lands and eventually began expanding the borders of Greater Iran.

Following Nader Shah, many of the other leaders of the Afsharid dynasty were weak and the state they had built quickly gave way to the Qajars. As the control of the country de-centralised with the collapse of Nader Shah's rule, many of the peripheral territories of the Empire gained independence and only paid token homage to the Persian State.

Zand Dynasty (1750-1794)

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2011) |

Qajar Era (1794 to 1925)

The second half of the 18th Century saw a new dynasty take hold in Iran. The new Qajar dynasty was founded on slaughter and plunder of Iranians, particularly Zoroasterian Iranians. The rise of the Qajars was very closely timed with Catherine the Great's order to invade Iran once again. During the Persian Expedition of 1796, Russian troops crossed the Aras River and invaded parts of Azarbaijan and Gilan, while they also moved to Lankaran with the aim of occupying Rasht again. The Qajars, under their dynasty founder, Agha Mohammad Khan plundered and slaughtered Zand Dynasty. This viscious dynasty then defeated the Russian in several important battles[citation needed]. Agha Mohammad Khan, with 60,000 cavalry under his command, drove the Russians back[citation needed] beyond Tbilisi. Following the capture of Georgia, Agha Mohammad Khan was murdered by two of his servants who feared they would be executed. His nephew and successor, Fath Ali Shah, after several successful campaigns of his own against the Afshars, with the help of Minister of War Mirza Assadolah Khan and Minister Amir Kabir created a new strong army, based on the latest European models, for the newly chosen Crown-Prince Abbas Mirza.

This period marked a decline in Persia's power and thus its military prowess. From here onwards the Qajar dynasty would face great difficulty in its efforts, due to the international policies mapped out by some western great powers and not Persia herself. Persia's efforts would also be weakened due to continual economic, political, and military pressure from outside of the country (see The Great Game), and social and political pressures from within would make matters worse.

In 1803, Russia invaded[citation needed] and annexed[citation needed] Georgia, and then moved south towards Armenia and Azarbaijan. In the Russo-Persian War (1806-1813) the Russians were victorious. From the beginning, Russian troops had a great advantage over the Persians as they possessed modern Artillery, the use of which had never sunk into the Persian army since the Safavid dynasty three centuries earlier. Nevertheless, the Persian army under the command of Abbas Mirza managed to win several victories over the Russians. Iran's inability to develop modern artillery during the preceding, and the Qajar, dynasty resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. This marked a turning point in the Qajar attitude towards the military. Abbas Mirza sent a large number of Persians to England to study Western military technology and at the same time he invited British officers to Persia to train the Persian forces under his command. The army's transformation was phenomenal as can be seen from the Battle of Erzeroum (1821) where the new army routed an Ottoman army. This resulted in the Treaty of Erzeroum whereby the Ottoman Empire acknowledged the existing frontier between the two empires. These efforts to continue the modernisation of the army through the training of officers in Europe continued until the end of the Qajar dynasty. With the exceptions of Russian and Imperial British armies, the Qajar army of the time was unquestionably the most powerful in the region.

With his new army, Abbas Mirza invaded Russia in 1826. The Persian army proved no match for the significantly larger and equally capable Russian army. The following Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 crippled Persia through the ceding of much of Persia's northern territories and the payment of a colossal war indemnity. The scale of the damage done to Persia through the treaty was so severe that The Persian Army and state would not regain its former strength till the rise and creation of the Soviet Union and the latter's cancellation of the economic elements of the treaty as 'tsarist imperialistic policies'.

The reigns of both Mohammad Shah and Nasser ed-Din Shah also saw attempts by Persia to bring the city of Herat, occupied by the Afghans, again under Persian rule. In this, though the Afghans were no match for the Persian Army, the Persians were not successful, this time because of British Intervention as part of The Great Game (See papers by Waibel and Esandari Qajar within the Qajar Studies source). Russia backed the Persian attacks, using Persia as a 'cat's paw' for expansion of its own interests. Britain feared the seizure of Herat would leave a route to attack India controlled by a power friendly to Russia, and threatened Persia with closure of the trade of the Persian Gulf. When Persia abandoned its designs on Herat, the British no longer felt India was threatened. This, combined with growing Persian fears about Russian designs on their own country, led to the later period of Anglo-Persian military co-operation.

Ultimately, under the Qajars Persia was shaped into its modern form. Initially, under the reign of Agha Mohammad Khan Persia won back control of several independent regions and the northern territories, only to be lost again through a series of bitter wars with Russia. In the west the Qajars effectively stopped Ottoman encroachment and in the east the situation remained fluid. Ultimately, through Qajar rule the military institution was further developed and a capable and regionally superior military force was developed. This was quashed by the then superpowers of the day: Russia and Britain.

For World War I, see the Persian Campaign.

Pahlavi Era (1925 to 1979)

When the Pahlavi dynasty came through power the Qajar dynasty was already weak from years of war with Russia. The standing Persian army was almost non-existent. The new king Reza Shah Pahlavi, was quick to develop a new military. In part, this involved sending hundreds of officers to European and American military academies. It also involved having foreigners re-train the existing army within Iran. In this period the Iranian Air Force was established and the foundation for a new Navy was laid.

Following Germany's invasion of the USSR in June 1941, Britain and the Soviet Union became allies. Both saw the newly opened Trans-Iranian Railroad as a strategic route to transport supplies from the Persian Gulf to the Soviet region. In August 1941, Britain and the USSR invaded Iran and deposed Reza Shah Pahlavi in favor of his son Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. Following the end of the Second World War Iran's independence was respected and both countries withdrew.

Following a number of clashes in April 1969, international relations with Iraq fell into a steep decline, mainly due to a dispute over the Shatt al-Arab waterway in the 1937 Algiers Accord. Iran abrogated the 1937 accord and demanded a renegotiation which ended completely in its favor. Furthermore, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi embarked on an unprecedented modernisation program for the armed forces. In many cases Iran was being supplied with advanced weaponry even before it was supplied to the armies of the countries that developed it[citation needed]. The Iranian military, while very well armed and trained at this point was totally reliant on external suppliers for its equipment. By 1978 Iran had the worlds 5th strongest and largest army and was the clear undisputed regional superpower. During this period of strength Iran protected its interests militarily in the region: In Oman, the Dhofar Rebellion was quashed. In November 1971 Iranian forces seized control of three uninhabited but strategic islands at the mouth of the Persian Gulf.

-

Imperial Iranian Ground Force (IIGF)

-

Imperial Iranian Navy (IIN)

-

Imperial Iranian Air Force (IIAF)

Islamic Republic of Iran (1979 to Present)

In 1979, the year of the Shah's departure and the revolution, the Iranian military experienced a 60% desertion from its ranks. Following the ideological principles of the Islamic revolution in Iran, the new revolutionary government sought to strengthen its domestic situation by conducting a purge of senior military personnel closely associated with the Pahlavi Dynasty. It is still unclear how many were dismissed or executed. The purge encouraged the dictator of Iraq, Saddam Hussein to view Iran as disorganised and weak, leading to the Iran–Iraq War. The indecisive eight year war wreaked havoc on the region and the Iranian military, only coming to an end in 1988 after it expanded into the Persian Gulf and led to clashes between the United States Navy and Iranian military forces between 1987-1988. Following the Iran–Iraq War an ambitious military rebuilding program was set into motion with the intention to create a fully fledged military industry.

Regionally, since the Islamic Revolution, Iran has sought to exert its influence by supporting various groups (militarily and politically). It openly supports Hizbullah in Lebanon in order to influence Lebanon. Various Kurdish groups are also supported as needed in order to maintain control of its Kurdish regions. In neighbouring Afghanistan, Iran supported the Northern Alliance for over a decade against the Taliban, and nearly went to war against the Taliban in 1998.[24]

-

Army of Iran

-

Revolutionary Guards

-

Police of Iran

See also

References

- ^ Parthia (2): the empire

- ^ George Rawlinson, The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, 2002, Gorgias Press LLC ISBN 1-931956-48-0

- ^ Milani A. Lost Wisdom. 2004 ISBN 0-934211-90-6 p.15

- ^ Mohammad Mohammadi Malayeri, Tarikh-i Farhang-i Iran (Iran's Cultural History). 4 volumes. Tehran. 1982.

- ^ ʻAbd al-Ḥusayn Zarrīnʹkūb (1379 (2000)). Dū qarn-i sukūt : sarguz̲asht-i ḥavādis̲ va awz̤āʻ-i tārīkhī dar dū qarn-i avval-i Islām (Two Centuries of Silence). Tihrān: Sukhan. OCLC 46632917. ISBN 964-5983-33-6.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Hatch Dupree, Nancy. "Sites in Perspective". An Historical Guide To Afghanistan.

- ^ Britannica, Saffarid dynasty

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Edition, 2007, "Samanid Dynasty", LINK

- ^ Daniel, Elton L. The History of Iran. p. 74.

- ^ Busse, Heribert (1975), "Iran Under the Buyids", in Frye, R. N., The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, page 270: "Aleppo remained a buffer between the Buyid empire and Byzantium".

- ^ [1]

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica: "Deylamites"

- ^ Islamic Central Asia: an anthology of historical sources, Ed. Scott Cameron Levi and Ron Sela, (Indiana University Press, 2010), 83; "The Ghaznavids were a dynasty of Turkic slave-soldiers..."

- ^ C.E. Bosworth: The Ghaznavids. Edinburgh, 1963

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Ghaznavid Dynasty", Online Edition 2007

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2005). The Atlas of World History. American Edition, New York: Covent Garden Books. pp. 65, 228. ISBN 9780756618612. This map varies from other maps which are slightly different in scope, especially along the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (New Brunswick:Rutgers University Press, 1988), 147.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991)

- ^ John Perry, "The Historical Role of Turkish in Relation to Persian of Iran", Iran & the Caucasus, Vol. 5, (2001), pp. 193-200.

- ^ M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK)

- ^ Biran, Michel, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian history, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 44.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Khwarezm-Shah-Dynasty", (LINK)

- ^ The History Files Rulers of Persia

- ^ "Iran's gulf of misunderstanding with US". BBC News. 25 September 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

Further reading

- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2006). Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period. Legat Verlag. ISBN 978-3932942228.

- The Middle East: 2000 Years of History From The Rise of Christianity to the Present Day, Bernard Lewis, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995.

- Qajar Studies: War and Peace in the Qajar Era, Journal of the Qajar Studies Association, London: 2005.

- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2009). "Las Técnicas de la Esgrima Persa". Revista de Artes Marciales Asiáticas (in Spanish). 4 (1): 20–49.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2009). "Persian Firearms Part One: The Matchlocks". Classic Arms and Militaria. XVI (1): 42–47.

- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2009). "Persian Firearms Part Two: The Flintlock". Classic Arms and Militaria. XVI (2): 22–26.