The Prince of Egypt: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

''The Prince of Egypt'' received generally positive reviews from critics and at [[Rotten Tomatoes]], based on 80 reviews collected, the film has an overall approval rating of 79%, with a [[weighted average]] score of 7/10.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/prince_of_egypt/|title=The Prince of Egypt movie reviews|work=[[Rotten Tomatoes]]|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> [[Metacritic]], which assigns a [[Standard score|normalized]] 0–100 rating to reviews from mainstream critics, calculated an average score of 64 from the 26 reviews it collected.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/princeofegypt?q=prince%20of%20egypt|title=The Prince of Egypt (1998): Reviews|work=[[Metacritic]]|publisher=''CNET Networks''|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> |

''The Prince of Egypt'' received generally positive reviews from critics and at [[Rotten Tomatoes]], based on 80 reviews collected, the film has an overall approval rating of 79%, with a [[weighted average]] score of 7/10.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/prince_of_egypt/|title=The Prince of Egypt movie reviews|work=[[Rotten Tomatoes]]|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> [[Metacritic]], which assigns a [[Standard score|normalized]] 0–100 rating to reviews from mainstream critics, calculated an average score of 64 from the 26 reviews it collected.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/princeofegypt?q=prince%20of%20egypt|title=The Prince of Egypt (1998): Reviews|work=[[Metacritic]]|publisher=''CNET Networks''|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> |

||

[[Roger Ebert]] of the ''[[Chicago Sun-Times]]'' praised the film in his review saying, "''The Prince of Egypt'' is one of the best-looking animated films ever made. It employs computer-generated animation as an aid to traditional techniques, rather than as a substitute for them, and we sense the touch of human artists in the vision behind the Egyptian monuments, the lonely desert vistas, the thrill of the chariot race, the personalities of the characters. This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children's entertainment."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19981218/REVIEWS/812180303/1023|title=The Prince of Egypt: Roger Ebert|publisher=[[Chicago Suntimes]]|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> [[Richard Corliss]] of ''[[Time (magazine)|Time]]'' magazine gave a negative review of the film saying, "The film lacks creative exuberance, any side pockets of joy."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989841-1,00.html|title=Can a Prince be a movie king? - TIME|publisher=[[Time Magazine]]|accessdate=March 12, 2009 | date=December 14, 1998 | first=Richard | last=Corliss}}</ref> [[Stephen Hunter]] from ''[[The Washington Post]]'' praised the film saying, "The movie's proudest accomplishment is that it revises our version of Moses toward something more immediate and believable, more humanly knowable."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/princeofegypthunter.htm|title=The Prince of Egypt: Review|publisher=The Washington Post|accessdate=February 27, 2009 | date=September 7, 1999}}</ref> ''Lisa Alspector'' from the ''[[Chicago Reader]]'' praised the film and wrote, "The blend of animation techniques somehow demonstrates mastery modestly, while the special effects are nothing short of magnificent."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://onfilm.chicagoreader.com/movies/capsules/17161_PRINCE_OF_EGYPT|title=The Prince of Egypt: Review|publisher=[[Chicago Reader]]|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> ''[[Houston Chronicle]]'''s Jeff Millar reviewed by saying, "The handsomely animated ''Prince of Egypt'' is an amalgam of Hollywood biblical epic, Broadway supermusical and nice Sunday school lesson."<ref>{{cite news|last=Millar|first=Jeff|title=Prince of Egypt|url=http://www.chron.com/entertainment/movies/article/Prince-of-Egypt-1991413.php|accessdate=April 4, 2012|newspaper=Houston Chronicle|date=December 18, 1998}}</ref> [[James Berardinelli]] from ''Reelviews'' highly praised the film saying, "The animation in The Prince of Egypt is truly top-notch, and is easily a match for anything Disney has turned out in the last decade", and also wrote "this impressive achievement uncovers yet another chink in Disney's once-impregnable animation armor."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.reelviews.net/movies/p/prince_egypt.html|title=Review:The Prince of Egypt|publisher=Reelviews.net|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> Liam Lacey of ''[[The Globe and Mail]]'' gave a somewhat negative review and wrote, "''Prince of Egypt'' is spectacular but takes itself too seriously."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/ArticleNews/movie/MOVIEREVIEWS/19981218/TALAIM|title=The Globe and Mail Review:The Prince of Egypt|publisher=[[The Globe and Mail]]|accessdate=March 12, 2009 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20040818045143/http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/ArticleNews/movie/MOVIEREVIEWS/19981218/TALAIM |archivedate = August 18, 2004}}</ref> |

[[Roger Ebert]] of the ''[[Chicago Sun-Times]]'' praised the film in his review saying, "''The Prince of Egypt'' is one of the best-looking animated films ever made. It employs computer-generated animation as an aid to traditional techniques, rather than as a substitute for them, and we sense the touch of human artists in the vision behind the Egyptian monuments, the lonely desert vistas, the thrill of the chariot race, the personalities of the characters. This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children's entertainment."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19981218/REVIEWS/812180303/1023|title=The Prince of Egypt: Roger Ebert|publisher=[[Chicago Suntimes]]|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> [[Richard Corliss]] of ''[[Time (magazine)|Time]]'' magazine gave a negative review of the film saying, "The film lacks creative exuberance, any side pockets of joy."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989841-1,00.html|title=Can a Prince be a movie king? - TIME|publisher=[[Time Magazine]]|accessdate=March 12, 2009 | date=December 14, 1998 | first=Richard | last=Corliss}}</ref> [[Stephen Hunter]] from ''[[The Washington Post]]'' praised the film saying, "The movie's proudest accomplishment is that it revises our version of Moses toward something more immediate and believable, more humanly knowable."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/princeofegypthunter.htm|title=The Prince of Egypt: Review|publisher=The Washington Post|accessdate=February 27, 2009 | date=September 7, 1999}}</ref> ''Lisa Alspector'' from the ''[[Chicago Reader]]'' praised the film and wrote, "The blend of animation techniques somehow demonstrates mastery modestly, while the special effects are nothing short of magnificent."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://onfilm.chicagoreader.com/movies/capsules/17161_PRINCE_OF_EGYPT|title=The Prince of Egypt: Review|publisher=[[Chicago Reader]]|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> ''[[Houston Chronicle]]'''s Jeff Millar reviewed by saying, "The handsomely animated ''Prince of Egypt'' is an amalgam of Hollywood biblical epic, Broadway supermusical and nice Sunday school lesson."<ref>{{cite news|last=Millar|first=Jeff|title=Prince of Egypt|url=http://www.chron.com/entertainment/movies/article/Prince-of-Egypt-1991413.php|accessdate=April 4, 2012|newspaper=Houston Chronicle|date=December 18, 1998}}</ref> [[James Berardinelli]] from ''Reelviews'' highly praised the film saying, "The animation in The Prince of Egypt is truly top-notch, and is easily a match for anything Disney has turned out in the last decade", and also wrote "this impressive achievement uncovers yet another chink in Disney's once-impregnable animation armor."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.reelviews.net/movies/p/prince_egypt.html|title=Review:The Prince of Egypt|publisher=Reelviews.net|accessdate=February 27, 2009}}</ref> Liam Lacey of ''[[The Globe and Mail]]'' gave a somewhat negative review and wrote, "''Prince of Egypt'' is spectacular but takes itself too seriously."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/ArticleNews/movie/MOVIEREVIEWS/19981218/TALAIM|title=The Globe and Mail Review:The Prince of Egypt|publisher=[[The Globe and Mail]]|accessdate=March 12, 2009 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20040818045143/http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/ArticleNews/movie/MOVIEREVIEWS/19981218/TALAIM |archivedate = August 18, 2004}}</ref> [[MovieGuide]] also reviewed the film favorably, giving it a rare 4 out of 4 stars, saying that, "''The Prince of Egypt'' takes animated movies to a new level of entertainment. Magnificent art, music, story, and realization combine to make ''The Prince of Egypt'' one of the most entertaining masterpieces of all time."<ref>[http://www.movieguide.org/reviews/the-prince-of-egypt.html Movie Review: The Prince of Egypt]</ref> |

||

===Awards=== |

===Awards=== |

||

| Line 167: | Line 167: | ||

==Banning== |

==Banning== |

||

''The Prince of Egypt'' was banned in two countries where the population is predominantly Muslim: the [[Maldives]] and [[Malaysia]], on the grounds that the depiction in the media of Islamic prophets (among which [[Islamic view of Moses|Moses is counted]]) is forbidden in Islam. The Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs in the Maldives stated: "All [[Prophets in Islam|prophets]] and [[Apostle (Islam)|messengers]] of [[God]] are revered in Islam, and therefore cannot be portrayed".<ref>"There can be miracles", ''[[The Independent]]'', January 24, 1999</ref><ref>{{cite news |url= http://www.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/News/9901/27/showbuzz/index.html |accessdate= March 12, 2009 |title= CNN Showbuzz — January 27, 1999 |date= January 27, 1999 |publisher= CNN}}</ref> Following this ruling, the censor board banned the film in January 1999. In the same month, the Film Censorship Board in Malaysia banned the film, but did not provide a specific explanation. The board's secretary said that the censor body ruled the film was "insensitive for religious and moral reasons". <ref name=bbc>{{cite news |url= http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/263905.stm |accessdate= July 17, 2007 |title= Malaysia bans Spielberg's Prince |date= January 27, 1999 |publisher= BBC News}}</ref> |

''The Prince of Egypt'' was banned in two countries where the population is predominantly Muslim: the [[Maldives]] and [[Malaysia]], on the grounds that the depiction in the media of Islamic prophets (among which [[Islamic view of Moses|Moses is counted]]) is forbidden in Islam. The Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs in the Maldives stated: "All [[Prophets in Islam|prophets]] and [[Apostle (Islam)|messengers]] of [[God]] are revered in Islam, and therefore cannot be portrayed".<ref>"There can be miracles", ''[[The Independent]]'', January 24, 1999</ref><ref>{{cite news |url= http://www.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/News/9901/27/showbuzz/index.html |accessdate= March 12, 2009 |title= CNN Showbuzz — January 27, 1999 |date= January 27, 1999 |publisher= CNN}}</ref> Following this ruling, the censor board banned the film in January 1999. In the same month, the Film Censorship Board in Malaysia banned the film, but did not provide a specific explanation. The board's secretary said that the censor body ruled the film was "insensitive for religious and moral reasons". <ref name=bbc>{{cite news |url= http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/263905.stm |accessdate= July 17, 2007 |title= Malaysia bans Spielberg's Prince |date= January 27, 1999 |publisher= BBC News}}</ref> |

||

==Prequel== |

==Prequel== |

||

Revision as of 20:37, 10 March 2014

| The Prince of Egypt | |

|---|---|

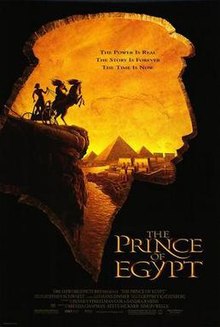

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Simon Wells Brenda Chapman Steve Hickner |

| Screenplay by | Philip LaZebnik Nicholas Meyer |

| Produced by | Penney Finkelman Cox Sandra Rabins Jeffrey Katzenberg (executive producer) |

| Starring | Val Kilmer Ralph Fiennes Michelle Pfeiffer Sandra Bullock Jeff Goldblum Patrick Stewart Danny Glover Steve Martin Martin Short |

| Edited by | Nick Fletcher |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer (Score) Stephen Schwartz (Songs) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | DreamWorks Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English / Hebrew |

| Budget | $70 million[1] |

| Box office | $218,613,188[1] |

The Prince of Egypt is a 1998 American animated epic musical semi-historical drama film and the first traditionally animated film produced and released by DreamWorks Animation. The film is an adaptation of the Book of Exodus and follows Moses' life from being a prince of Egypt to his ultimate destiny to lead the children of Israel out of Egypt. The film was directed by Brenda Chapman, Simon Wells and Steve Hickner. The film featured songs written by Stephen Schwartz and a score composed by Hans Zimmer. The voice cast featured a number of major Hollywood actors in the speaking roles, while professional singers replaced them for the songs, except for Michelle Pfeiffer, Ralph Fiennes, Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Ofra Haza (who sang her song in over seventeen languages for the film's dubbing), who sang their own parts.

The film was nominated for best Original Musical or Comedy Score and won for Best Original Song at the 1999 Academy Awards for "When You Believe".[2] The song's pop version was performed at the ceremony by Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey. The song, co-written by Stephen Schwartz, Hans Zimmer and with additional production by Babyface, was nominated for Best Original Song (in a Motion Picture) at the 1999 Golden Globes,[3] and was also nominated for Outstanding Performance of a Song for a Feature Film at the ALMA Awards.

The film was released in theaters on December 18, 1998, and on home video on September 14, 1999. The film went on to gross $218,613,188 worldwide in theaters,[1] making it the second animated feature not released by Disney to gross over $100 million in the U.S. after Paramount/Nickelodeon's The Rugrats Movie. The Prince of Egypt became the top grossing non-Disney animated film until 2000 when it was out-grossed by the stop motion film Chicken Run (another DreamWorks film). The film also remained the highest grossing traditionally-animated non-Disney film until 2007, when it was out-grossed by 20th Century Fox's The Simpsons Movie.[4] This is DreamWorks Animation's only traditionally-animated film to win an Oscar and one of the three DreamWorks Animation films to be nominated for more than one Oscar.

Plot

In Ancient Egypt, Yocheved, a Hebrew slave, and her children, Miriam and Aaron, watch as Hebrew babies are taken and ruthlessly killed by Egyptian soldiers, as ordered by Pharaoh Seti I, who fears an increase in the Hebrew population could lead to an uprising. To save her own newborn son, Yocheved places him in a basket and sets it afloat on the Nile, praying that God will deliver him to a safe fate. Miriam follows the basket and witnesses her baby brother being taken in by the Egyptian Queen Tuya, who names him Moses.

Twenty years later, Moses and his foster brother, Rameses, are lectured by their father after they destroy a temple during one of their youthful misadventures. Rameses is berated for their misdeeds though Moses tries to take the blame; Moses later remarks that Rameses wants the approval of his father more than anything, but lacks the opportunity. Seeking to give him this opportunity, Seti names Rameses Prince Regent and gives him authority over all of Egypt's temples. In thanks, Rameses appoints Moses as Royal Chief Architect. As a tribute to Rameses, the high priests Hotep and Huy offer him Tzipporah, a young Midian woman they kidnapped, as a concubine. After she nearly bites him, Rameses gives her to Moses, who ultimately helps her escape captivity. While following her out of the city, Moses is reunited with Miriam and Aaron. Miriam tells Moses the truth about his past, despite Aaron's protests, and Moses denies it until Miriam starts to sing a lullaby that Yocheved sang for him the day she saved his life. That same evening, Moses has a nightmare that causes him to realize the truth. Moses asks Seti about the murder of the Hebrew babies; through his reply, Moses realizes that Seti considers the Hebrews inferior to him. The next day, Moses accidentally pushes an Egyptian guard off the scaffolding of the temple while trying to stop him from whipping a Hebrew slave, and the guard falls to his death. Ashamed and confused, Moses decides to go into hiding, despite Rameses' pleas that he stay.

Moses crosses many miles of desert, and eventually reaches the land of the Midianites, Tzipporah's people, who worship the Hebrew God. After Moses saves Tzipporah's sisters from bandits, he is welcomed warmly into the tribe by their father Jethro, the High Priest of Midian. After assimilating in this new culture, Moses becomes a shepherd and gradually earns Tzipporah's respect and love, culminating in their marriage. One day, while chasing a stray lamb, Moses discovers a burning bush through which God speaks to him. God instructs Moses to free the Hebrew slaves and take them to the promised land, and bestows Moses' shepherding staff with his power.

Moses then returns to Egypt with Tzipporah, entering the palace in the midst of a large celebration. He is happily greeted by Rameses, now Pharaoh and the father of a young prince. Moses tells Rameses to let the Hebrews go, demonstrating the power of God by changing his shepherding staff into an egyptian cobra. Hotep and Huy boastfully "repeat" this transformation by using illusions to turn two staffs into two snakes, only to have their snakes eaten by Moses' snake. Having not believed his brother, Rameses takes Moses to the throne room where Moses discloses that he has honestly returned to free the Hebrews, and rather than being persuaded, Rameses is hardened and orders the Hebrew's workload to be doubled. Moses and Tzipporah go to live with Miriam, who forgives Moses for his former disbelief, and convinces Aaron and the other Hebrews to trust him. Later, Moses confronts Rameses passing in his boat on the Nile. Rameses orders his guards to bring Moses to him, but they draw back when Moses turns the river water into blood with his staff; the first Plague of Egypt. Similarly to the earlier competition, Hotep and Huy use trickery and dye to make a bowl of water appear to be blood as well. Convinced of the might of the Egyptian gods and his own divinity, Rameses, again, refuses to free the Hebrews.

As the days pass, God causes eight more of the Plagues of Egypt occur through Moses' staff. The plagues ravage Egypt, its monuments, and people. Moses feels tortured to inflict such horrors on the innocent, and is heartbroken to see his former home in ruins. Despite all the pain and destruction caused by the plagues, Rameses refuses to relent, and in anger, when Moses confronts him again, vows to finish the work his father started against the Hebrews, unwittingly providing the stipulations of the final plague. Moses, with nothing left to say to Rameses, resigns himself to preparing the Hebrews for the tenth and final plague. He instructs them to paint lamb's blood above their doors for the coming night of Passover. That night, the final plague, the angel of death goes through the country, killing all the firstborn children of Egypt, including Rameses' own son, while sparing those of the Hebrews. The next day, Moses visits Rameses one last time, who finally gives him the permission to free the Hebrews and take them out of Egypt. Moses weeps at the sight of his dead nephew and for all his brother's pain.

The following morning, the Hebrews leave Egypt, led by Moses, Miriam, Aaron, and Tzipporah. They are weary at first, but soon begin to heal and find hope and happiness. They eventually find their way to the Red Sea, but as they are resting, they discover that Rameses has changed his mind and is closely pursuing them with his army. With only a few minutes separating the Hebrews from the Egyptians, Moses uses his staff to part the sea, while a pillar of fire blocks the army's way. The Hebrews cross on the open sea bottom; when the pillar of fire disappears and the army gives chase, the water closes over the Egyptian soldiers, and the Hebrews are safe. However, Rameses is spared, and he is hurled back to the shore by the collapsing waves, screaming Moses' name in anguish. Saddened by what he and Rameses have lost forever, Moses bids his brother goodbye one last time and leads the Hebrew people to Mount Sinai, where he receives the Ten Commandments from God.

Cast

- Val Kilmer as Moses, a Hebrew who was adopted by Pharaoh Seti.

- Val Kilmer also provides (uncredited) the voice of God

- Amick Byram provides Moses' singing voice.

- Ralph Fiennes as Rameses II, Moses' adoptive brother and eventual successor to his father, Seti.

- Michelle Pfeiffer as Tzipporah, Jethro's oldest daughter and Moses' wife.

- Sandra Bullock as Miriam, Moses and Aaron's biological sister.

- Sally Dworsky provides Miriam's singing voice.

- Eden Riegel provides both the speaking and singing voice of a younger Miriam.

- Jeff Goldblum as Aaron, Moses and Miriam's biological brother.

- Patrick Stewart as Pharaoh Seti I, Rameses' father, Moses' adoptive father and the first Pharaoh in the film. Despite his uncaring attitude towards the Hebrew slaves, he is shown to treat Moses and Rameses with good care and love.

- Danny Glover as Jethro, Tzipporah's father and Midian's high priest.

- Brian Stokes Mitchell provides Jethro's singing voice.

- Helen Mirren as Queen Tuya, Seti's consort wife, Rameses' mother and Moses' adoptive mother.

- Linda Dee Shayne provides Queen Tuya's singing voice.

- Steve Martin as Hotep

- Martin Short as Huy

- Ofra Haza as Yocheved, the biological mother of Miriam, Aaron, and Moses.

Director Brenda Chapman briefly voices Miriam when she sings the lullaby to Moses. The vocal had been recorded for a scratch audio track, which was intended to be replaced later by Sally Dworsky. The track turned out so well that it remained in the film.

Production

Development

Former Disney chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg had always wanted to do an animated adaption of The Ten Commandments. While working for The Walt Disney Company, Katzenberg suggested this idea to Michael Eisner, but he refused. The idea for the film was brought back at the formation of DreamWorks, when Katzenberg's partners, Amblin Entertainment founder Steven Spielberg, and music producer David Geffen, were meeting in Spielberg's living room.[5] Katzenberg recalls that Spielberg looked at him during the meeting and said, "You ought to do The Ten Commandments."[5]

The Prince of Egypt was "written" throughout the story process. Beginning with a starting outline, Story Supervisors Kelly Asbury and Lorna Cook led a team of fourteen storyboard artists and writers as they sketched out the entire film — sequence by sequence. Once the storyboards were approved, they were put into the Avid Media Composer digital editing system by editor Nick Fletcher to create a "story reel" or animatic. The story reel allowed the filmmakers to view and edit the entire film in continuity before production began, and also helped the layout and animation departments understand what is happening in each sequence of the film.[6] After casting of the voice talent concluded, dialogue recording sessions began. For the film, the actors record individually in a studio under guidance by one of the three directors. The voice tracks were to become the primary aspect as to which the animators built their performances.[6] Because DreamWorks was concerned about theological accuracy, Jeffrey Katzenberg decided to call in Biblical scholars, Christian, Jewish and Muslim theologians, and Arab American leaders to help his film be more accurate and faithful to the original story. After previewing the developing film, all these leaders noted that the studio executives listened and responded to their ideas, and praised the studio for reaching out for comment from outside sources.[5]

Design

Art directors Kathy Altieri and Richard Chavez and Production Designer Darek Gogol led a team of nine visual development artists in setting a visual style for the film that was representative of the time, the scale and the architectural style of Ancient Egypt.[6] Part of the process also included the research and collection of artwork from various artists, as well as taking part in trips such as a two-week travel across Egypt by the filmmakers before the film's production began.[6]

There are 1192 scenes in the film, and 1180 of them have special effects in them. These special effects were elements such as wind blowing or environmental features such as dust or rainwater. There were also effects design in terms of lighting, as it casts its shadows and images into a given scene. In the end, these effects helped the animators graphically illustrate scenes such as the ten plagues of Egypt and the parting of the Red Sea.[5]

Character Designers Carter Goodrich, Carlos Grangel and Nicolas Marlet worked on setting the design and overall look of the characters. Drawing on various inspirations for the widely known characters, the team of character designers worked on designs that had a more realistic feel than the usual animated characters up to that time.[6] Both character design and art direction worked to set a definite distinction between the symmetrical, more angular look of the Egyptians versus the more organic, natural look of the Hebrews and their related environments.[6] The Backgrounds department, headed by supervisors Paul Lasaine and Ron Lukas, oversaw a team of artists who were responsible for painting the sets/backdrops from the layouts. Within the film, approximately 934 hand-painted backgrounds were created.[6]

Audio

The task of creating God's voice was given to Lon Bender and the team working with the film's music composer, Hans Zimmer.[7] "The challenge with that voice was to try to evolve it into something that had not been heard before," says Bender. "We did a lot of research into the voices that had been used for past Hollywood movies as well as for radio shows, and we were trying to create something that had never been previously heard not only from a casting standpoint but from a voice manipulation standpoint as well. The solution was to use the voice of actor Val Kilmer to suggest the kind of voice we hear inside our own heads in our everyday lives, as opposed to the larger than life tones with which God has been endowed in prior cinematic incarnations."[7] As a result, in the final film, Kilmer gave voice to Moses and God, as well, yet the suggestion is that someone else would have heard God speak to him again in his own voice.

Composer and lyricist Stephen Schwartz began working on writing songs for the film from the very beginning of the film's production. As the story evolved, he continued to write songs that would serve to both entertain and help move the story along. Composer Hans Zimmer arranged and produced the songs and then eventually wrote the film's score. The film's score was recorded entirely in London, England.[6]

Three soundtracks were released simultaneously for The Prince of Egypt, each of them aimed towards a different target audience and one was promoted by faith guru Rick Hendrix. While the other two accompanying records, the country-themed "Nashville" soundtrack and the gospel-based "Inspirational" soundtrack, functioned as film tributes, the official The Prince of Egypt soundtrack contained the actual songs from the film.[8] This album combines elements from the score composed by Hans Zimmer, and film songs by Stephen Schwartz.[8] The songs were either voiced over by professional singers (such as Salisbury Cathedral Choir), or sung by the film's voice actors, such as Michelle Pfeiffer and Ofra Haza. Various tracks by contemporary artists such as K-Ci & JoJo and Boyz II Men were added, including the Mariah Carey and Whitney Houston duet "When You Believe", a Babyface rewrite of the original Schwartz composition, sung by Michelle Pfeiffer and Sally Dworsky in the film. Amy Grant also sings a version of "River Lullaby".

Reception

Box office performance

On its opening weekend, the film grossed $14,524,321 for a $4,658 average from 3,118 theaters, earning second place at the box office, behind You've Got Mail. Due to the holiday season, the film gained 4% in its second weekend, earning $15,119,107 and finishing in fourth place. It had a $4,698 average from 3,218 theaters. It would hold well in its third weekend, with only a 25% drop to $11,244,612 for a $3,511 average from 3,202 theaters and once again finishing in fourth place. The film closed on May 27, 1999 after earning a domestic total gross of $101,413,188 and an additional $117,200,000 overseas for a worldwide total of $218.6 million.

| Source | Gross (USD) | % Total | All Time Rank (Unadjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States & Canada | $101,413,188[1] | 46.4% | 398[1] |

| Foreign | $117,200,000[1] | 53.6% | – |

| Worldwide | $218,613,188[1] | 100.0% | 319[1] |

Reviews

The Prince of Egypt received generally positive reviews from critics and at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 80 reviews collected, the film has an overall approval rating of 79%, with a weighted average score of 7/10.[9] Metacritic, which assigns a normalized 0–100 rating to reviews from mainstream critics, calculated an average score of 64 from the 26 reviews it collected.[10]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times praised the film in his review saying, "The Prince of Egypt is one of the best-looking animated films ever made. It employs computer-generated animation as an aid to traditional techniques, rather than as a substitute for them, and we sense the touch of human artists in the vision behind the Egyptian monuments, the lonely desert vistas, the thrill of the chariot race, the personalities of the characters. This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children's entertainment."[11] Richard Corliss of Time magazine gave a negative review of the film saying, "The film lacks creative exuberance, any side pockets of joy."[12] Stephen Hunter from The Washington Post praised the film saying, "The movie's proudest accomplishment is that it revises our version of Moses toward something more immediate and believable, more humanly knowable."[13] Lisa Alspector from the Chicago Reader praised the film and wrote, "The blend of animation techniques somehow demonstrates mastery modestly, while the special effects are nothing short of magnificent."[14] Houston Chronicle's Jeff Millar reviewed by saying, "The handsomely animated Prince of Egypt is an amalgam of Hollywood biblical epic, Broadway supermusical and nice Sunday school lesson."[15] James Berardinelli from Reelviews highly praised the film saying, "The animation in The Prince of Egypt is truly top-notch, and is easily a match for anything Disney has turned out in the last decade", and also wrote "this impressive achievement uncovers yet another chink in Disney's once-impregnable animation armor."[16] Liam Lacey of The Globe and Mail gave a somewhat negative review and wrote, "Prince of Egypt is spectacular but takes itself too seriously."[17] MovieGuide also reviewed the film favorably, giving it a rare 4 out of 4 stars, saying that, "The Prince of Egypt takes animated movies to a new level of entertainment. Magnificent art, music, story, and realization combine to make The Prince of Egypt one of the most entertaining masterpieces of all time."[18]

Awards

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[2] | Best Original Musical or Comedy Score | Nominated | |

| Best Original Song | "When You Believe" | Won | |

| Annie Awards[19] | Best Animated Feature | Nominated | |

| Individual Achievement in Directing | Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner, and Simon Wells | Nominated | |

| Individual Achievement in Storyboarding | Lorna Cook (Story supervisor) | Nominated | |

| Individual Achievement in Effects Animation | Jamie Lloyd (Effects Lead — Burning Bush/Angel of Death) | Nominated | |

| Individual Achievement in Voice Acting | Ralph Fiennes ("Rameses") | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[3] | Best Original Score | Nominated | |

| Best Original Song | "When You Believe" | Nominated |

Banning

The Prince of Egypt was banned in two countries where the population is predominantly Muslim: the Maldives and Malaysia, on the grounds that the depiction in the media of Islamic prophets (among which Moses is counted) is forbidden in Islam. The Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs in the Maldives stated: "All prophets and messengers of God are revered in Islam, and therefore cannot be portrayed".[20][21] Following this ruling, the censor board banned the film in January 1999. In the same month, the Film Censorship Board in Malaysia banned the film, but did not provide a specific explanation. The board's secretary said that the censor body ruled the film was "insensitive for religious and moral reasons". [22]

Prequel

In November 2000, DreamWorks Animation released Joseph: King of Dreams, a direct-to-video prequel based on the story of Joseph from the Book of Genesis.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Prince of Egypt (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "Academy Awards, USA: 1998". awardsdatabase.oscars.org. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ a b "HFPA-Awards search". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Highest grossing animated films". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Dan Wooding's strategic times". Assistnews.net. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Prince of Egypt-About the Production". Filmscouts.com. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b "Sound design of Prince of Egypt". Filmsound.org. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "SoundtrackNet:The Prince of Egypt Soundtrack". SoundtrackNet.net. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ "The Prince of Egypt movie reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Prince of Egypt (1998): Reviews". Metacritic. CNET Networks. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Prince of Egypt: Roger Ebert". Chicago Suntimes. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 14, 1998). "Can a Prince be a movie king? - TIME". Time Magazine. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ^ "The Prince of Egypt: Review". The Washington Post. September 7, 1999. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Prince of Egypt: Review". Chicago Reader. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ Millar, Jeff (December 18, 1998). "Prince of Egypt". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Review:The Prince of Egypt". Reelviews.net. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Globe and Mail Review:The Prince of Egypt". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on August 18, 2004. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ^ Movie Review: The Prince of Egypt

- ^ "Legacy: 22nd Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (1999)". Annie Awards. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "There can be miracles", The Independent, January 24, 1999

- ^ "CNN Showbuzz — January 27, 1999". CNN. January 27, 1999. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ^ "Malaysia bans Spielberg's Prince". BBC News. January 27, 1999. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- The Jewish study Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, http://www.booktopia.com.au/the-jewish-study-bible-adele-berlin/prod9780195297515.html. Web. Apr 5, 2013. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=aDuy3p5QvEYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Jewish+study+Bible&hl=en&ei=unbbTonKMZGQiQejvpjdDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=The%20Jewish%20study%20Bible&f=false

- “Man.” Genetically Change in Ancient Egypt 2.4 (1967): 551-568. JSTOR. Web. Apr 5, 2013. <http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.hclib.org/stable/2799339?&Search=yes&searchText=Egypt&searchText

- Cerny, Jaroslav. “The Will of Naunakhte and the Related Documents.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 31 (1945): 29-53. JSTOR. Web. Apr 6, 2013. <www.jstor.org.ezproxy.hclib.or>.

- Toivari, Jaana i. “Man versus Woman: Interpersonal Disputes in the Workmen’s Community of Deir el-Medina.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 40.2 (1997): 153-173. JSTOR. Web. Apr 6, 2013. <http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.hclib.org/stable/3632680?seq=4&Search>.

External links

- Official website archived from the original on April 12, 2001

- The Prince of Egypt at IMDb

- Template:Bcdb title

- The Prince of Egypt at AllMovieInvalid ID.

- The Prince of Egypt at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Prince of Egypt at Box Office Mojo

- 1998 films

- English-language films

- American animated films

- American coming-of-age films

- American musical drama films

- DreamWorks Animation animated films

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- Musicals based on the Bible

- Christian animation

- Films about Jews and Judaism

- DreamWorks films

- Epic films

- Films about the ten plagues of Egypt

- Films based on the Hebrew Bible

- Films set in ancient Egypt

- Films set in Africa

- Moses

- Religious epic films

- Screenplays by Nicholas Meyer

- Films set in the 13th century BC

- Films directed by Brenda Chapman

- Films directed by Simon Wells

- Films directed by Steve Hickner

- Animated drama films

- Animated adventure films

- Animated musical films

- Animated romance films

- Films based on the Quran

- Film scores by Hans Zimmer

- Films about slavery

- Best Animated Feature Broadcast Film Critics Association Award winners