Polykleitos: Difference between revisions

m separating sentence, removing ref tag that isn't really a ref, and not parenthetical enough to go into a separate note |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

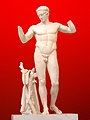

[[Image:Doryphoros.jpg|thumb|150px|Polykleitos' ''[[Doryphoros]]'' (Spear-Bearer), an early example of classical ''[[contrapposto]]''.]] |

[[Image:Doryphoros.jpg|thumb|150px|Polykleitos' ''[[Doryphoros]]'' (Spear-Bearer), an early example of classical ''[[contrapposto]]''.]] |

||

'''Polykleitos''' was an ancient [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[Sculpture|sculptor]] in [[bronze]] of the 5th century BCE. His Greek name was traditionally Latinized ''Polycletus'', but is also transliterated ''Polycleitus''; ({{lang-grc|Πολύκλειτος}}, "much-renowned") and due to [[iotacism]] in the transition from Ancient to Modern Greek, ''Polyklitos'' or ''Polyclitus''. He is called ''Sicyonius'' (lit. "The Sicyonian", usually translated as "of Sicyon") <ref>[[Pliny the Elder]] ''[[Natural Histories]]'' 34.19.23</ref> by Latin authors including [[Pliny the Elder]] and [[Cicero]], and Ἀργείος (lit. "The Argive", trans. "of Argos") by others like Plato and Pausanias. He is sometimes called the Elder, in cases where it is necessary to distinguish him from his son, a major architect but minor sculptor. |

'''Polykleitos''' was an ancient [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[Sculpture|sculptor]] in [[bronze]] of the 5th century BCE. His Greek name was traditionally Latinized ''Polycletus'', but is also transliterated ''Polycleitus''; ({{lang-grc|Πολύκλειτος}}, "much-renowned") and due to [[iotacism]] in the transition from Ancient to Modern Greek, ''Polyklitos'' or ''Polyclitus''. He is called ''Sicyonius'' (lit. "The Sicyonian", usually translated as "of Sicyon") <ref>[[Pliny the Elder]] ''[[Natural Histories]]'' 34.19.23</ref> by Latin authors including [[Pliny the Elder]] and [[Cicero]], and Ἀργείος (lit. "The Argive", trans. "of Argos") by others like [[Plato]] and ]]Pausanias]]. He is sometimes called the Elder, in cases where it is necessary to distinguish him from his son, a major architect but minor sculptor. |

||

Alongside the [[Athens|Athenian]] sculptors [[Pheidias]], [[Myron]] and [[Praxiteles]], he is considered one of the most important sculptors of [[Classical antiquity]]. The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to [[Xenocrates]] (the "Xenocratic catalogue"), which was [[Pliny the Elder|Pliny's]] guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron.<ref>Andrew Stewart, "Polykleitos of Argos," ''One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works'', 16.73</ref> |

Alongside the [[Athens|Athenian]] sculptors [[Pheidias]], [[Myron]] and [[Praxiteles]], he is considered one of the most important sculptors of [[Classical antiquity]]. The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to [[Xenocrates]] (the "Xenocratic catalogue"), which was [[Pliny the Elder|Pliny's]] guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron.<ref>Andrew Stewart, "Polykleitos of Argos," ''One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works'', 16.73</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:53, 24 June 2015

Polykleitos was an ancient Greek sculptor in bronze of the 5th century BCE. His Greek name was traditionally Latinized Polycletus, but is also transliterated Polycleitus; (Ancient Greek: Πολύκλειτος, "much-renowned") and due to iotacism in the transition from Ancient to Modern Greek, Polyklitos or Polyclitus. He is called Sicyonius (lit. "The Sicyonian", usually translated as "of Sicyon") [1] by Latin authors including Pliny the Elder and Cicero, and Ἀργείος (lit. "The Argive", trans. "of Argos") by others like Plato and ]]Pausanias]]. He is sometimes called the Elder, in cases where it is necessary to distinguish him from his son, a major architect but minor sculptor.

Alongside the Athenian sculptors Pheidias, Myron and Praxiteles, he is considered one of the most important sculptors of Classical antiquity. The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to Xenocrates (the "Xenocratic catalogue"), which was Pliny's guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron.[2]

Early life and training

As noted above, Polykleitos is called "The Sicyonian" by some authors, all writing in Latin, and who modern scholars view as relying on an error of Pliny the Elder in conflating another more minor sculptor from Sikyon, a disciple of Phidias, with Polykleitos of Argos. Pausanias is adamant that they were not the same person, and that Polykleitos was from Argos, in which city state he must have received his early training,[3] and a contemporary of Phidias (possibly also taught by Ageladas).

Works

Polykleitos' figure of an Amazon for Ephesus was regarded as superior to those by Pheidias and Kresilas at the same time[citation needed], while his colossal gold and ivory statue of Hera which stood in her temple—the Heraion of Argos—was favourably compared with the Olympian Zeus by Pheidias. He also sculpted a famous bronze male nude known as the Doryphoros ("Spear-carrier"), which survives in the form of numerous Roman marble copies. Further sculptures attributed to Polykleitos are the Discophoros ("Discus-bearer"), Diadumenos ("Youth tying a headband")[4] and a Hermes at one time placed, according to Pliny, in Lysimachia (Thrace). Polykleitos' Astragalizontes ("Boys Playing at Knuckle-bones") was claimed by the Emperor Titus and set in a place of honour in his atrium.[5] Pliny also mentions that Polykleitos was one of the five major sculptors who competed in the fifth century B.C. to make a wounded Amazon for the temple of Artemis; marble copies associated with the competition survive.[6]

Style

Polykleitos, along with Phidias, created the Classical Greek style. Although none of his original works survive, literary sources identifying Roman marble copies of his work allow reconstructions to be made. Contrapposto was a posture in his statues in which the weight was placed on one leg, and was a source of his fame.

The refined detail of Polykleitos' models for casting executed in clay is revealed in a famous remark repeated in Plutarch's Moralia, that "the work is hardest when the clay is under the fingernail".[7]

The Kanon and symmetria

Polykleitos consciously created a new approach to sculpture, writing a treatise (Kanon) and designing a male nude (also known as Kanon) exemplifying his aesthetic theories of the mathematical bases of artistic perfection. These expressions motivated Kenneth Clark to place him among "the great puritans of art":[8] Polykleitos' Kanon "got its name because it had a precise commensurability (symmetria) of all the parts to one another"[9] "His general aim was clarity, balance, and completeness; his sole medium of communication the naked body of an athlete, standing poised between movement and repose" Kenneth Clark observed.[10] Though the Kanon was probably represented by his Doryphoros, the original bronze statue has not survived. References to it in other ancient writings, however, imply that its main principle was expressed by the Greek words symmetria, the Hippocratic principle of isonomia ("equilibrium"), and rhythmos. "Perfection, he said, comes about little by little (para mikron) through many numbers".[11] By this Polykleitos meant that a statue should be composed of clearly definable parts, all related to one another through a system of ideal mathematical proportions and balance.

The method begins with one part, such as the last (distal) phalange of the little finger, treated as one side of a square. Rotating that square's diagonal gives a 1 : √2 rectangle, suitable for the next (medial) phalange. The method is repeated to get the next phalange, then (using the whole finger) to get the palm; then using the whole hand to get the forearm to the elbow, then the forearm to get the upper arm.[12]

Followers

Polykleitos and Phidias were amongst the first generation of Greek sculptors to attract schools of followers. Polykleitos' school lasted for at least three generations, but it seems to have been most active in the late 4th century and early 3rd century BCE. The Roman writers Pliny and Pausanias noted the names of about twenty sculptors in Polykleitos' school, defined by their adherence to his principles of balance and definition. Skopas and Lysippus are among the best-known successors of Polykleitos.

Polykleitos' son, Polykleitos the Younger, worked in the 4th century BCE. Although the son was also a sculptor of athletes, his greatest fame was won as an architect. He designed the great theater at Epidaurus.

The main-belt asteroid 5982 Polykletus is named after Polykleitos.

Gallery

-

A Polykleitan Diadumenos, in a Roman marble copy, National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

-

Discophoros, British Museum.

-

Wounded Amazon, Musei Capitolini, Rome.

Notes

- ^ Pliny the Elder Natural Histories 34.19.23

- ^ Andrew Stewart, "Polykleitos of Argos," One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works, 16.73

- ^ That a "school of Argos" existed during the fifth century is minimized as "marginal" by Jeffery M. Hurwit, "The Doryphoros: Looking Backward", in Warren G. Moon, ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition, 1995:3-18.

- ^ "Statue of Diadoumenos (youth tying a fillet around his head)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia

- ^ "Statue of a wounded Amazon". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia, quoted in Stewart.

- ^ Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, 1956:63;"...they derive the principles of their art, as if from a law of some kind, and he alone of men is deemed to have rendered art itself in a work of art." Pliny's Natural History, 34.55-6.

- ^ Galen, De Temperamentis.

- ^ Clark 1956:63.

- ^ Philo, Mechanicus, quoted in Stewart.

- ^ Lawton, Arthur J. (2013). "Pattern, Tradition and Innovation in Vernacular Architecture". Past. 36.

he base figure is a square the length and width of the distal phalange of the little finger. Its diagonals rotated to one side transform the square to a 1 : √2 root rectangle. In Figure 5 this rectangular figure marks the width and length of the adjacent medial phalange. Rotating the medial diagonal proportions the proximal phalange and similarly from there to the wrist, from wrist to elbow and from elbow to shoulder top. Each new step advances the diagonal's pivot point.

References

- Pausanias, Description of Greece.

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/sculpture/polykleitos.htm

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Polyclitus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.