Gross-Rosen concentration camp: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→External links: add link to collection of testimonies concerning Gross-Rosen camp |

||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

{{Commons|KZ Gross-Rosen}} |

{{Commons|KZ Gross-Rosen}} |

||

* The [[Death marches (Holocaust)|Death March]] [http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/volary_death_march/index.asp through Schlesiersee to Volary], at [[Yad Vashem]] website |

* The [[Death marches (Holocaust)|Death March]] [http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/volary_death_march/index.asp through Schlesiersee to Volary], at [[Yad Vashem]] website |

||

* [http://www.chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/results?action=AdvancedSearchAction&type=-3&search_attid1=62&search_value1=Mass+extermination+%E2%80%93+KL+Gross%5C-Rosen Collection of testimonies concerning Gross-Rosen camp in 'Chronicles of Terror' database] |

|||

{{The Holocaust|camps}} |

{{The Holocaust|camps}} |

||

Revision as of 08:43, 28 March 2017

50°59′57″N 16°16′40″E / 50.999281°N 16.277704°E

| Gross-Rosen | |

|---|---|

| Nazi concentration camp | |

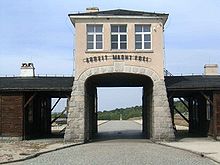

Model of the Gross-Rosen main camp, from the Rogoźnica Museum [1] Location of Gross-Rosen at Rogoźnica, Poland | |

| Operation | |

| Period | Summer of 1940 – February 14, 1945 |

| Prisoners | |

| Total | 125,000 (in estimated 100 subcamps) |

| Victims | 40,000 |

Gross-Rosen concentration camp (Template:Lang-de) was a German network of Nazi concentration camps built and operated during World War II. The main camp was located in the village of Gross-Rosen not far from the border with occupied Poland, in the modern-day Rogoźnica in Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland;[2] directly on the rail-line between the towns of Jawor (Jauer) and Strzegom (Striegau).[1][3]

At its peak activity in 1944, the Gross-Rosen complex had up to 100 subcamps located in eastern Germany, Czechoslovakia, and on the territory of occupied Poland. The population of all Gross-Rosen camps at that time accounted for 11% of the total number of inmates trapped in the Nazi concentration camp system.[2]

The camp

KZ Gross-Rosen was set up in the summer of 1940 as a satellite camp of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp from Oranienburg. Initially, the slave labour was carried out in a huge stone quarry owned by the SS-Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (SS German Earth and Stone Works).[3] In the fall of 1940 the utilization of labour in Upper Silesia was taken over by the new Organization Schmelt formed on the orders of Heinrich Himmler. It was named after its leader SS-Oberführer Albrecht Schmelt. The company was put in charge of employment from the camps with Jews intended to work for food only. The Gross-Rosen location close to occupied Poland was of considerable advantage.[4] Prisoners were put to work in the construction of a system of subcamps for expelees from the annexed territories. Gross Rosen became an independent camp on May 1, 1941. As the complex grew, the majority of inmates were put to work in the new Nazi enterprises attached to these subcamps.[3]

In October 1941 the SS transferred about 3,000 Soviet POWs to Gross-Rosen for execution by shooting. Gross-Rosen was known for its brutal treatment of the so-called Nacht und Nebel prisoners vanishing without a trace from targeted communities. Most died in the granite quarry. The brutal treatment of the political and Jewish prisoners was not only in the hands of guards and German criminal prisoners brought in by the SS, but to a lesser extent also fuelled by the German administration of the stone quarry responsible for starvation rations and denial of medical help. In 1942, for political prisoners, the average survival time-span was less than two months.[3]

Due to a change of policy in August 1942, prisoners were likely to survive longer because they were needed as slave workers in German war industries. Among the companies that benefited from the slave labour of the concentration camp inmates were German electronics manufacturers such as Blaupunkt or Siemens, as well as Krupp, IG Farben, and Daimler-Benz among others.[5] Some prisoners who were not able to work but not yet dying, were sent to the Dachau concentration camp in so-called invalid transports. The largest population of inmates, however, were Jews, initially from the Dachau and Sachsenhausen camps, and later from Buchenwald. During the camp's existence, the Jewish inmate population came mainly from Poland and Hungary; others were from Belgium, France, Netherlands, Greece, Yugoslavia, Slovakia, and Italy.

Subcamps

At its peak activity in 1944, the Gross-Rosen complex had up to 100 subcamps,[2] located in eastern Germany, Czechoslovakia, and occupied Poland. In its final stage, the population of the Gross-Rosen camps accounted for 11% of the total inmates in Nazi concentration camps at that time. A total of 125,000 inmates of various nationalities passed through the complex during its existence, of whom an estimated 40,000 died on site, on death marches and in evacuation transports. The camp was liberated on February 14, 1945, by the Red Army.

A total of over 500 female camp guards were trained and served in the Gross-Rosen complex. Female SS staffed the women's subcamps of Brünnlitz, Graeben, Gruenberg, Gruschwitz Neusalz, Hundsfeld, Kratzau II, Oberaltstadt, Reichenbach, and Schlesiersee Schanzenbau.

A subcamp of Gross-Rosen situated in the Czechoslovakian town of Brünnlitz (Brněnec) was a location where Jews rescued by Oskar Schindler were interned.

Camp commandants

During the Gross-Rosen initial period of operation as a formal subcamp of Sachsenhausen, the following two SS Lagerführer officers served as the camp commandants, the SS-Untersturmführer Anton Thumann, and SS-Untersturmführer Georg Gussregen. From May 1941 until liberation, the following officials served as commandants of a fully independent concentration camp at Gross-Rosen:

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Arthur Rödl, May 1941 – September 1942

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Wilhelm Gideon, September 1942 – October 1943

- SS-Sturmbannführer Johannes Hassebroek, October 1943 until evacuation

List of Gross-Rosen camps with location

The most far-reaching expansion of the Gross-Rosen system of labour camps took place in 1944 due to accelerated demand for support behind the advancing front. The character and purpose of new camps shifted toward defense infrastructure. In some cities, as in Wrocław (Breslau) camps were established in every other district. It is estimated that their total number reached 100 at that point according to list of their official destinations. The biggest sub-camps included AL Fünfteichen in Jelcz-Laskowice, four camps in Wrocław, Dyhernfurth in Brzeg Dolny, Landeshut in Kamienna Góra, and the entire Project Riese along the Owl Mountains.[6]

- Aslau (Osła)

- Bad Warmbrunn (Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój)

- Bautzen (in Bautzen)

- Bernsdorf (in Bernartice)

- Birnbäumel (Gruszeczka)

- Bolkenhain (Bolków)

- Brandhofen (in Brandhofen)

- Breslau I (Wrocław)

- Breslau II (Wrocław)

- Breslau-Hundsfeld (Wrocław)

- Breslau-Lissa (Wrocław-Leśnica)

- Brieg-Pampitz (in Pępice)

- Brünnlitz

- Buchwald-Hohenwiese

- Bunzlau I (Boleslawiec)

- Bunzlau II

- Christianstadt (Krzystkowice)

- Dyhernfurth I (Brzeg Dolny)

- Dyhernfurth II (Brzeg Dolny)

- Freiburg (Świebodzice)

- Friedland (Mieroszów)

- Fünfteichen (Miłoszyce)

- Fürstenstein (Książ)

- Gabersdorf (in Trutnov)

- Gablonz

- Gassen (Jasień)

- Gebhardsdorf (Giebułtów)

- Geppersdorf

- Görlitz (Zgorzelec)

- Gräben (Grabina, Strzegom)

- Grafenort (Gorzanów)

- Gräflich-Röhrsdorf (Skarbowa Wrocław) [6]

- Gross Koschen

- Gross-Rosen (Rogoźnica)

- Grulich (Kraliky)

- Grünberg I

- Grünberg II

- Guben (Gubin)

- Halbau (Ilowa)

- Halbstadt (Meziměstí)

- Hartmannsdorf (Miłoszów)

- Hausdorf (Jugowice)

- Hirschberg (Jelenia Góra)

- Hochweiler (Wierzchowice)

- Hohenelbe (Vrchlabi)

- Hundsfeld (Psie Pole)

- Kaltenbrunn (Studzienno)

- Kaltwasser (Zimna)

- Kamenz (Kamenz)

- Kittlitztreben (Trzebień)

- Klein Radisch (Radšowk [de])

- Königszelt (Jaworzyna)

- Kratzau I (Chrastava)

- Kratzau II (Zitt-Werke AG)

- Kunnerwitz

- Kurzbach (Bukołowo, Milicz)[7]

- Landeshut (Kamienna Góra)

- Langenbielau I (Bielawa)

- Langenbielau II

- Lärche (Glinica)

- Liebau (Lubawka)

- Ludwigsdorf (Ludwikowice)

- Mährisch Weisswasser (Bílá Voda)

- Markstädt (Jelcz-Laskowice)

- Merzdorf (Marciszów)[6]

- Mittelsteine (Ścinawka Średnia)

- Morchenstern (Smržovka) [8]

- Namslau (Namysłów)

- Neiße (Nysa)

- Neusalz (Nowa Sól)

- Niederoderwitz (near Zittau)

- Niesky (in Niesky)

- Nimptsch (Niemcza)

- Ober Altstadt (Staré Město)

- Ober Hohenelbe

- Parschnitz I (Poříčí [cz])

- Parschnitz II (Poříčí)[9]

- Peterswaldau (Pieszyce)

- Rauscha (Ruszów)

- Reichenau (Rychnov)

- Reichenbach (Dzierżoniów)

- Rennersdorf

- Sackisch

- Schatzlar

- Schertendorf (Przylep)

- Schlesiersee I (Sława)

- Schlesiersee II

- St. Georgenthal (Jiřetín)

- St. Georgenthal II

- Treskau (Owińska)

- Waldenburg (Wałbrzych)

- Weisswasser

- Wiesau

- Wüstegiersdorf (Głuszyca Górna)

- Zillerthal-Erdmannsdorf

- Zittau [6]

Notable inmates

- Boris Braun, Croatian University professor

- Simon Wiesenthal, Nazi hunter. He provides the following information about the camp in his 1967 book The Murderers Among Us:

- "...healthy looking prisoners were selected to break in new shoes for soldiers on daily twenty mile marches. Few prisoners survived this ordeal for more than two weeks."

- Władysław Ślebodziński, mathematician who taught prisoners

- Franciszek Duszeńko, sculptor, author of Treblinka Monument

- Adam Dulęba, Polish Army photographer

See also

- List of Nazi-German concentration camps

- List of subcamps of Gross Rosen

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Nazi crimes against the Polish nation

- Project Riese

Notes

- ^ a b The Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica. Homepage.

- ^ a b c "Historia KL Gross-Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum. 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Alfred Konieczny (pl), Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust. NY: Macmillan 1990, vol. 2, pp. 623–626.

- ^ Dr Tomasz Andrzejewski, Dyrektor Muzeum Miejskiego w Nowej Soli (8 January 2010), "Organizacja Schmelt" Marsz śmierci z Neusalz. Skradziona pamięć! Tygodnik Krąg. Template:Pl icon

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia (2014), Gross-Rosen. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ a b c d "Filie obozu Gross-Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum (Muzeum Gross Rosen w Rogoźnicy). Retrieved 16 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Prezes Rady Ministrów: J. Buzek (20 September 2001). "Rozporządzenie Prezesa Rady Ministrów w sprawie określenia miejsc odosobnienia, w których były osadzone osoby narodowości polskiej lub obywatele polscy innych narodowości". Dziennik Ustaw Nr 106, Poz. 1154. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ May be spelled 'Morgenstern'

- ^ Tenhumberg Reinhard (2014). "Parschnitz: Außenlager des Konzentrationslagers Groß-Rosen, Zwangsarbeitslager für Juden" (in German). Familie Tenhumberg. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

References

- Harthoorn, W.L. (2007). Verboden te sterven: Oranjehotel, Kamp Amersfoort, Buchenwald, Grosz-Rozen, Dachau, Natzweiler. ISBN 978-90-75879-37-7.

- Willem Lodewijk Harthoorn (nl), an inmate from the end of April to mid-August 1942: Verboden te sterven (in Dutch: Forbidden to Die), Pegasus, Amsterdam.

- Teunissen, Johannes (2002). Mijn belevenissen in de duitse concentratiekampen. ISBN 978-90-435-0367-9.

- Druhasvetovavalka.cz collection of photographs from the KZ Gross-Rosen World War II field trip.