Coca: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses}} |

{{otheruses}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Taxobox |

{{Taxobox |

||

| color = lightgreen |

| color = lightgreen |

||

| Line 15: | Line 17: | ||

| binomial_authority = [[Jean-Baptiste Lamarck|Lam.]]}} |

| binomial_authority = [[Jean-Baptiste Lamarck|Lam.]]}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

'''Coca''' is a [[plant]] in the [[family (biology)|family]] [[Erythroxylaceae]], native to north-western [[South America]]. The plant plays a significant role in traditional [[Andean culture]]. It is used by Andean cultures such as the Chibcha family of Colombia and Quechua family of Peru as a messenger from the Gods, but is best-known in most of the world for the stimulant drug [[cocaine]] that is chemically extracted from its new fresh leaf tips in a similar fashion to [[Tea|tea bush]] harvesting. Unprocessed coca leaves are also commonly used in the Andean countries to make a [[herbal tea]] with mild [[stimulant]] effects similar to strong [[coffee]]. |

'''Coca''' is a [[plant]] in the [[family (biology)|family]] [[Erythroxylaceae]], native to north-western [[South America]]. The plant plays a significant role in traditional [[Andean culture]]. It is used by Andean cultures such as the Chibcha family of Colombia and Quechua family of Peru as a messenger from the Gods, but is best-known in most of the world for the stimulant drug [[cocaine]] that is chemically extracted from its new fresh leaf tips in a similar fashion to [[Tea|tea bush]] harvesting. Unprocessed coca leaves are also commonly used in the Andean countries to make a [[herbal tea]] with mild [[stimulant]] effects similar to strong [[coffee]]. |

||

Revision as of 02:22, 15 October 2007

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. |

| Coca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | E. coca

|

| Binomial name | |

| Erythroxylum coca | |

Coca is a plant in the family Erythroxylaceae, native to north-western South America. The plant plays a significant role in traditional Andean culture. It is used by Andean cultures such as the Chibcha family of Colombia and Quechua family of Peru as a messenger from the Gods, but is best-known in most of the world for the stimulant drug cocaine that is chemically extracted from its new fresh leaf tips in a similar fashion to tea bush harvesting. Unprocessed coca leaves are also commonly used in the Andean countries to make a herbal tea with mild stimulant effects similar to strong coffee.

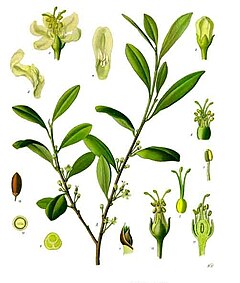

The plant resembles a blackthorn bush, and grows to a height of 2–3 m (7–10 ft). The branches are straight, and the leaves, which have a green tint, are thin, opaque, oval, more or less tapering at the extremities. A marked characteristic of the leaf is an areolated portion bounded by two longitudinal curved lines, one line on each side of the midrib, and more conspicuous on the under face of the leaf.

The flowers are small, and disposed in little clusters on short stalks; the corolla is composed of five yellowish-white petals, the anthers are heart-shaped, and the pistil consists of three carpels united to form a three-chambered ovary. The flowers mature into red berries.

The leaves are sometimes eaten by the larvae of the moth Eloria noyesi.

Species and classification

There are twelve main species and varieties. Two subspecies, Erythroxylum coca var. coca and E. coca var. ipadu, are almost indistinguishable phenotypically; a related high cocaine-bearing species has two subspecies, E. novogranatense var. novogranatense and E. novogranatense var. truxillense that are phenotypically similar, but morphologically distinguishable. Under the older Cronquist system of classifying flowering plants, this was placed in an order Linales; more modern systems place it in the order Malpighiales.

Cultivation and uses

Coca is traditionally cultivated in the lower altitudes of the eastern slopes of the Andes, or the highlands depending on the species grown. Since ancient times, its leaves have been used as a stimulant by some of the Andean people of Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia, where unprocessed coca remains legal and popular today as a common herbal tea with mild stimulant effects. In the highlands, coca tea and chewed leaves are used as a breathing aid to combat the effects of altitude sickness.

Coca leaf is the raw material for the manufacture of the drug cocaine, a powerful stimulant and anaesthetic extracted chemically from large quantities of coca leaves. Today, cocaine is best known as an illegal recreational drug popular in Europe and North America. Cocaine was often sold as a patent medicine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries before its proscription, and cocaine remains legal (though uncommon and highly regulated) for medical use as a local anaesthetic in many jurisdictions, used particularly for dental, throat, and nasal surgery. See cocaine.

Though legal and traditionally well-established within the local societies, the unrestricted cultivation of coca in the Andes has been opposed since the 1980s by the United States government because the leaf can be refined into cocaine destined for the recreational drug market, which is illegal in most countries. The money derived from cocaine sales has been used by both left-wing and right-wing insurgent and paramilitary groups in the Andes to finance their operations, contributing significantly to political instability. The United States government has thus funded coca-eradication programs in Andean countries as a matter of policy, ranging from involuntary aerial spraying of herbicides on coca crops to programs designed to encourage local farmers to grow alternate crops.

Good fresh samples of the dried leaves are uncurled, are of a deep green on the upper, and a grey-green on the lower surface, and have a strong tea-like odor; when chewed they produce a pleasurable numbness in the mouth, and have a pleasant, pungent taste. They are traditionally chewed with lime to increase the release of cocaine from the leaf. Bad specimens, usually old or stale leaves, have a camphoraceous smell and a brownish colour, and lack the pungent taste.

The seeds are sown from December to January in small plots (almacigas) sheltered from the sun, and the young plants when at 40–60 cm in height are placed in final planting holes (aspi), or if the ground is level, in furrows (uachos) in carefully weeded soil. The plants thrive best in hot, damp and humid situations, such as the clearings of forests; but the leaves most preferred are obtained in drier localities, on the sides of hills. The leaves are gathered from plants varying in age from one and a half to upwards of forty years, but only the new fresh growth is harvested. They are considered ready for plucking when they break on being bent. The first and most abundant harvest is in March, after the rains; the second is at the end of June, the third in October or November. The green leaves (matu) are spread in thin layers on coarse woollen cloths and dried in the sun; they are then packed in sacks, which must be kept dry in order to preserve the quality of the leaves.

Pharmacological aspects

The pharmacologically active ingredient of coca is the alkaloid cocaine which is found in the amount of about 0.2% in fresh leaves. Besides cocaine, the coca leaf contains a number of other alkaloids, including methylecgonine cinnamate, benzoylecgonine, truxilline, hydroxytropacocaine, tropacocaine, ecgonine, cuscohygrine, dihydrocuscohygrine, nicotine and hygrine. Some of these non-psychoactive chemicals are still used for the flavouring of Coca-Cola. When chewed, coca acts as a stimulant to help suppress hunger sensations, thirst, and fatigue. The LD50 of coca extract is 3,450 mg/kg, however, the LD50 of the extract based on its cocaine content is 31.4 mg/kg.

History

The chewing of coca leaves is generally agreed to date back at least to the sixth century A.D. Moche period, and the subsequent Inca period, based on mummies found with a supply of coca leaves, pottery depicting the characteristic cheek bulge of a coca chewer, spatulas for extracting alkali and figured bags for coca leaves and lime made from precious metals, and gold representations of coca in special gardens of the Inca in Cuzco[1][2] Coca chewing may originally have been limited to the eastern Andes before its introduction to the Incas. As the plant was viewed as having a divine origin, its cultivation became subject to a state monopoly and its use restricted to nobles and a few favored classes (court orators, couriers, favored public workers, and the army) by the rule of the Topa Inca (1471-1493). As the Incan empire declined, the drug became more widely available. After some deliberation, Philip II of Spain issued a decree recognizing the drug as essential to the well-being of the Andean Indians but urging missionaries to end its religious use. The Spanish are believed to have effectively encouraged use of coca by an increasing majority of the population to increase their labor output and tolerance for starvation, but it is not clear that this was planned deliberately.

Traditional medical uses of coca were foremost as a stimulant to overcome exhaustion, hunger, and thirst. It also was used as an anaesthetic to alleviate the pain of rheumatism, wounds and sores, broken bones, sore eyes, childbirth, and during trephining operations on the skull. Because cocaine constricts blood vessels, the action of coca also served to oppose bleeding, and coca seeds were used for nosebleeds. Indigenous use of coca was also reported as a treatment for malaria, ulcers, asthma, to improve digestion, to guard against bowel laxity, as an aphrodisiac, and credited with improving longevity. European manufacturers of patent medicines eventually claimed an even wider variety of applications, and ultimately the plant was marketed to the public at large in soft drinks such as Coca-cola.

Typical coca consumption is about two ounces per day, and contemporary methods are believed to be unchanged from ancient times. Coca is kept in a woven pouch (chuspa or huallqui). A few leaves are chosen to form a quid (acullico) held between the mouth and gums. The consumer carefully uses a wooden stick (formerly, often a spatula of precious metal) to transfer an alkaline component into the quid without touching his flesh with the corrosive substance. The alkali component, usually kept in a gourd (ishcupuro or poporo), can be made by burning limestone to form unslaked quicklime, burning quinoa stalks, or the bark from certain trees, and may be called ilipta, tocra or mambe depending on its composition.[1][2]

The practice of chewing coca was most likely originally a simple matter of survival. The coca leaf contains many essential nutrients in addition to its more well-known mood-altering alkaloid. It is rich in protein and vitamins, and it grows in regions where other food sources are scarce. The boost in energy and strength provided by the cocaine in coca leaves was also very functional in an area where oxygen is scarce and extensive walking is essential. This was also used to alleviate the feeling of hunger, sleepiness and headaches linked to altitude and other altitude sicknesses. The coca plant was so central to the world-view of the Yunga and Aymara tribes of South America that time and distance were often measured in "cocada", the 45-minute intervals at which fresh lumps of coca would be taken, or the distance one could travel in that period. In testament of the significance of coca to indigenous cultures, it is widely believed that the word "coca" originally meant "plant."

Coca was also a vital part of the religious cosmology of the Andean tribes in the pre-Inca period as well as throughout the Inca Empire (Tahuantinsuyu). Coca was historically employed as an offering to the Sun, or to produce smoke at the great sacrifices; and the priests, it was believed, must chew it during the performance of religious ceremonies, otherwise the gods would not be appeased.

Traditional uses

The activity of chewing coca is called mambear, chacchar or acullicar, borrowed from Quechua, or in Bolivia, picchar, derived from the Aymara language. The Spanish masticar is also frequently used, along with the slang term "bolear," derived from the word "bola" or ball of coca pouched in the cheek while chewing. Doing so usually causes users to feel a tingling and numbing sensation in their mouths, similar to receiving Novocaine during a dental procedure. Even today, chewing coca leaves is a common sight in indigenous communities across the central Andean region, particularly in places like the mountains of Bolivia, where the cultivation and consumption of coca is as much a part of the national culture similar to chicha, like wine is to France or beer is to Germany. It also serves as a powerful symbol of indigenous cultural and religious identity, amongst a diversity of indigenous nations throughout South America. Bags of coca leaves are sold in local markets and by street vendors. Commercially manufactured coca teas are also available in most stores and supermarkets, including upscale suburban supermarkets.

Coca is still chewed in the traditional way, with a tiny quantity of ilucta (a preparation of the ashes of the quinoa plant) added to the coca leaves; it softens their astringent flavor and activates the alkaloids. Other names for this basifying substance are llipta in Peru and the Spanish word lejía, lye in English. Many of these materials are salty in flavor, but there are variations. The most common base in the La Paz area of Bolivia is a product known as lejía dulce (sweet lye) which is made from quinoa ashes mixed with anise and cane sugar, forming a soft black putty with a sweet and pleasing licorice flavor. In some places, baking soda is used under the name bico.

Coca is still held in veneration among some of the indigenous and mestizo peoples of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia and northern Argentina and Chile. It is believed by the miners of Cerro de Pasco to soften the veins of ore, if masticated (chewed) and thrown upon them (see also Cocomama). Coca leaves play a crucial part in offerings to the apus (mountains), Inti (the sun), or Pachamama (the earth). Coca leaves are often read in a form of divination analogous to reading tea leaves in other cultures.

In the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, on the Caribbean Coast of Colombia, coca is consumed by the Kogi, Arhuaco & Wiwa by using a special gadget called poporo. The poporo is the mark of manhood, but it is a female symbolic sex. It represents the womb and the stick is a phallic symbol. The movements of the stick in the poporo symbolize the sexual act. For a man the poporo is a good companion which means "food", "woman", "memory" and "meditation". Women are prohibited from using coca. It is important to stress that poporo is the symbol of manhood. But it is the woman who gives men their manhood. When the boy is ready to be married, his mother will initiate him in the use of the coca. This act of initiation is carefully supervised by the mama, a traditional leader.

Mate de coca, sometimes called "coca tea", is a tisane made from the leaves of the Coca plant (Eritroxilécea). The consumption of coca tea is a common occurrence in many South American countries. Coca tea is also used for medicinal and religious purposes by many indigenous tribes in the Andes. On the "Inca Trail" to Macchu Picchu, guides also serve coca tea with every meal because it is widely believed that it alleviates the symptoms of mild altitude sickness. And traditionally, official governmental persons travelling to La Paz in Bolivia are greeted by a mate de coca. News reports noted that Princess Anne and the late Pope John Paul II drank the beverage during visits to the region. Recently (June 24 2007) chairman of Microsoft Corp. and multi-billionaire, Bill Gates drank Coca Tea in The Inti Raymi or Sun festival in Cusco Peru, which begins at Coricancha temple and ends at the Sacsayhuamán fortress, takes place every June 24. The event, with the participation of 600 actors, is to commemorate the the ancient Incan ritual in which the Sun God was worshipped.

While Bolivia's Evo Morales and Venezuela's Hugo Chavez, along with hundreds of thousands of Andean coca growers, are seeking to expand legal markets for the venerable leaf, the Colombian government is moving in the opposite direction. For years, Bogota has allowed indigenous coca farmers to sell coca products, promoting the enterprise as one of the few successful commercial opportunities available to recognized tribes like the Nasa, who have grown it for years and regard it as sacred. But in February, the Colombian government quietly imposed a ban on the sale of products outside indigenous reserves.

Coca Sek -- better than Coca Cola

The Nasa are pointing the finger at Coca-Cola, which last fall lost a lengthy legal effort against Coca Sek, the Nasa's energy drink popular among the Colombian young. Coca Sek infringed on its copyright, the American soft drink giant argued. With the Colombian food safety agency, Invima, decision restricting coca sales coming scant months after Coca-Cola lost its battle against Coca Sek, the suspicions are natural.

But Invima said it is merely heeding the wishes of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). While Colombia formally adheres to the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which considers coca a drug to be eradicated, Colombian indigenous communities grow coca legally under indigenous autonomy provisions of the 1991 constitution, and have been selling coca products throughout Colombia. But last year, the INCB sent the Colombian foreign ministry a letter asking whether the "refreshing drink made from coca and produced by an Indian community" didn't violate the 1961 treaty.

While the treaty considers the coca plant a drug to be suppressed and eradicated, it also contains a provision allowing coca products to be used if the cocaine alkaloid has been extracted. That is Coca-Cola's loophole, and the Nasa call it hypocrisy.

"They lose their fight in October and then in February the government decides to prohibit Coca Sek," said David Curtidor, a Nasa in charge of the company that produces the drink. He is leading a legal challenge to the ban. In the meantime, the community is losing $15,000 a month from lost sales of Coca Sek and other coca products. "Why don't they also ban Coca-Cola? It's also made of coca leaves," he complained to the Associated Press.

Coca-Cola wouldn't confirm or deny to the AP that it even uses a cocaine-free coca extract, as is widely believed. It did deny having anything to do with Invima's decision. Invima told the AP Coca-Cola had no role.

But the Nasa are suspicious, and they're not the only ones who think Coca-Cola gets special treatment. Last year, Bolivia's Morales, a former coca grower union leader himself, complained to the UN General Assembly that "the coca leaf is legal for Coca Cola and illegal for medicinal purposes in our country and in the whole world."

And now, whether at the bidding of the INCB or Coca-Cola, Colombia is moving to strangle the legal market for coca, even as it leads the world in coca production despite $4 billion in US aid this decade and the widespread aerial spraying of herbicides. In so doing, it places itself directly against the current in a region where coca is increasingly gaining the respect it deserves and the power of the coca growers and supporters, is on the increase.

International use

Coca has a long history of export and use around the world—legal and illegal. Modern export of processed coca (as cocaine) to global markets is well documented, and coca leaves are exported for coca tea, as a food additive (Coca-Cola), and for medical use. Several pipes taken from Shakespeare's residence and dated to the seventeenth century have shown evidence of cocaine. Queen Victoria of England was also a cocaine user. The drug was first introduced to Europe in the 16th century.

In recent times, the governments of several South American countries, such as Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela, have defended and championed the traditional use of coca, as well as the modern uses of the leaf and its extracts in household products such as teas and toothpaste. Alan Garcia, president of Peru, has recommended its use in salads and other edible preparations. [1]

Sadly the ignorance has dominated some people in the Andes, like in Colombia where President Alvaro Uribe Velez clearly does not support the coca consumption by the whole country, while a great mayority of educated youths in the capital openly support the andean coca movement, as well as interest in learning about their amerindian roots.

Industrial use

Coca is used industrially in the cosmetics and food industries. The Coca-Cola Company used to buy 115 tons of coca leaf from Peru and 105 tons from Bolivia per year, which it has used as a flavouring ingredient in its Coca-Cola formula. [2][3] Coca is sold to the pharmaceutical industry where it is used for various anaesthetics. Coca is used to produce Coca tea by Enaco S.A. (National Company of the Coca) a government enterprise in Peru.[4] [5]

In Colombia, the Paeces, a Tierradentro (Cauca) indigenous community, started in December 2005 to produce a drink called "Coca Sek." The production method belongs to the resguardos of Calderas (Inzá) and takes about 150 kg of coca per 3,000 produced bottles.

Literary References

One of the best known examples of coca's reference in fiction is Patrick O'Brian's character, Stephen Maturin. In many of the more than twenty book series, a.k.a. Aubrey-Maturin series, Maturin expounds the benefits of coca. However, the reader is made aware of the truly addictive effects of the drug when rats, who have found the coca (Erythroxylum coca) and become seriously addicted, scour the ship looking for it.

Legality

International

Article 26 of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs states:

- If a Party permits the cultivation of the coca bush, it shall apply thereto and to coca leaves the system of controls as provided in article 23 respecting the control of the opium poppy, but as regards paragraph 2 (d) of that article, the requirements imposed on the Agency therein referred to shall be only to take physical possession of the crops as soon as possible after the end of the harvest.

- The Parties shall so far as possible enforce the uprooting of all coca bushes which grow wild. They shall destroy the coca bushes if illegally cultivated.

The Article 23 controls referred to in paragraph 1 are rules requiring opium-, coca-, and cannabis-cultivating nations to designate an agency to regulate said cultivation and take physical possession of the crops as soon as possible after harvest. Article 27 states that "The Parties may permit the use of coca leaves for the preparation of a flavouring agent, which shall not contain any alkaloids, and, to the extent necessary for such use, may permit the production, import, export, trade in and possession of such leaves". This provision is designed to accommodate Coca-Cola and other producers of coca products.

In Bolivia, the president Evo Morales (elected in December, 2005), a former coca growers union leader, has promised to legalize the cultivation and traditional use of coca. Morales asserts that "coca no es cocaína"—the coca leaf is not cocaine. During his speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations on 19 September 2006, he held a coca leaf in his hand to demonstrate its innocuity.[6]

In Hong Kong, Coca leaves are regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purporses. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without prescription can be fined HK$10,000. The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing the substance is a HK$5,000,000 fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a HK$1,000,000 fine and/or 7 years of imprisonment.

In Peru, private companies already manufacture coca leaf products.

More recently, coca has been reintroduced to the U.S. as a flavoring agent in the herbal liqueur Agwa. Coca Leaf Tea is also currently for sale on Amazon.com through an independent distributor.

See also

References

- ^ a b Robert C. Peterson, Ph.D. (1977-05). "NIDA research monograph #13: Cocaine 1977, Chapter I" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Eleanor Carroll, M.A. "Coca: the plant and its use" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-05-26.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- Turner C. E., Elsohly M. A., Hanuš L., Elsohly H. N. Isolation of dihydrocuscohygrine from Peruvian coca leaves. Phytochemistry 20 (6), 1403-1405 (1981)

- "History of Coca. The Divine Plant of the Incas" by W. Golden Mortimer, M.D. 576 pp. And/Or Press San Francisco, 1974. This title has no ISBN.

External links

- Shared Responsibility

- Legalize Coca Leaves – and Break the Consensus

- OneWorld.net Analysis: Blurred Vision on Coca Eradication

- The Coca Museum (A private museum in La Paz, Bolivia)

- Coca - Cocaine website of the Transnational Institute (TNI)

- Coca, Cocaine and the International Conventions Transnational Institute

- Enaco S.A. Peruvian Enterprise of the Coca, Official Website

- Coca Yes, Cocaine No? Legal Options for the Coca Leaf Transnational Institute (TNI), Drugs & Conflict Debate Paper 13, May 2006

- Coca leaf news page – Alcohol and Drugs History Society

Photos

- 27 original photos on coca growing in La Convención valley, Cuzco Province, Peru

- Harvesting coca in Yungas de La Paz, Bolivia

- Drying coca in the Chapare, Bolivia

- 16 photos of Coca Tea manufactured by Enaco S.A. in Peru