Goodfellas: Difference between revisions

m credits |

|||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

|[[Michael Vivalo]] || Nicky Eyes || Himself |

|[[Michael Vivalo]] || Nicky Eyes || Himself |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[ |

|[[Wyatt A. O'brien]] || "Spider" || [[Michael "Spider" Gianco]] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Tony Darrow]] || Sonny Bunz || [[Angelo McConnach]] |

|[[Tony Darrow]] || Sonny Bunz || [[Angelo McConnach]] |

||

Revision as of 19:16, 31 December 2008

| Goodfellas | |

|---|---|

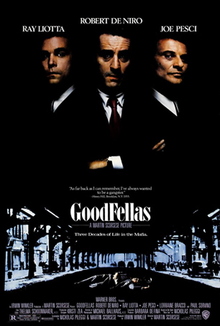

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Written by | Book: Nicholas Pileggi Screenplay: Nicholas Pileggi Martin Scorsese |

| Produced by | Irwin Winkler |

| Starring | Ray Liotta Robert De Niro Joe Pesci Lorraine Bracco Paul Sorvino |

| Narrated by | Ray Liotta Lorraine Bracco |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates | September, Template:Fy (Italy, premiere at VFF) September 19 (US) |

Running time | 148 min. |

| Country | Template:FilmUS |

| Language | Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. |

| Budget | $25,000,000 |

| Box office | $46,836,394 |

Goodfellas (also spelled GoodFellas) is a Template:Fy crime drama film directed by Martin Scorsese. It is based on the non-fiction book Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi, who also wrote the screenplay for Goodfellas with Scorsese. The film follows the rise and fall of three gangsters, spanning three decades.

Scorsese originally intended to direct Goodfellas before The Last Temptation of Christ, but when funds materialized to make Last Temptation, he postponed what was then known as Wise Guy. The title of Pileggi's book had already been used for a TV series and for Brian De Palma's 1986 comedy Wise Guys, so Pileggi and Scorsese changed the name of their film to Goodfellas.

To prepare for their roles in the film, Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Ray Liotta talked often with Pileggi, who shared with the actors research material that had been left over from writing the book. According to Pesci, improvisation and ad-libbing came out of rehearsals where Scorsese gave the actors freedom to do whatever they wanted. The director made transcripts of these sessions, took the lines that the actors came up with that he liked best, and put them into a revised script the cast worked from during principal photography.

Goodfellas performed well at the box office, grossing $46.8 million domestically, well above its $25 million budget; it received mostly strong positive reviews from critics. The film was nominated for six Academy Awards but only won one for Pesci in the Best Actor in a Supporting Role category. Scorsese's film won three awards from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts and was named best film of the year by the New York Film Critics Circle, the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and the National Society of Film Critics.

Plot

In the opening scene, main character Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) admits, "As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster," referring to his idolizing the Lucchese crime family gangsters in his blue-collar, predominantly Italian neighborhood in East New York, Brooklyn in the 1950’s. Feeling the connection of being a part of something, Henry quits school and goes to work for them. His father, knowing the true nature of the Mafia, tries to stop Henry after learning of his truancy, but the gangsters ensure that his parents no longer hear from the school by threatening the local postal carrier with dire consequences should he deliver any more letters from the school to Henry's house.

Henry is soon taken under the wing of the local mob captain, Paul "Paulie" Cicero (Paul Sorvino, based on the actual Lucchese mobster Paul Vario) and Cicero's close Irish associate Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro, based on Jimmy Burke). They help to cultivate Henry's criminal career, and introduce Henry to the entire network of Paulie’s crime syndicate.

Henry and his friends soon become successful, daring, and dangerous. Jimmy loves hijacking trucks, and Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci in his acclaimed Academy Award-winning performance based on Thomas DeSimone) is an aggressive psychopath with a hair-trigger temper. Henry commits the Air France Robbery and it marks his début into the big time of organized crime. Enjoying the perks of their criminal activities, the friends spend most of their nights at the Copacabana night club with countless women. Around this time, Henry meets and later marries a no-nonsense Jewish girl from the Five Towns named Karen (Lorraine Bracco). Karen at first is troubled by Henry's criminal activities, but when a neighbor assaults her for refusing his advances, Henry pistol-whips him in front of her, displaying all of the viciousness and confidence of proven gangsters. She feels vindicated, intrigued, and aroused by the fact, especially when Henry leaves her the gun he used on the culprit.

Violence is prevalent throughout the movie. On June 11, 1970 in Henry's restaurant, Tommy (with Jimmy's help) brutally beats Billy Batts (Frank Vincent), a prominent mobster of the Gambino crime family, for insulting him about being a shoeshine boy in his younger days. However, Batts was a made man, meaning that he could not even be physically attacked without the consent of his superiors. Realizing that this was an offense that could get all of them killed, Jimmy, Henry, and Tommy place the bloodied Batts in the trunk of of Henry's car intent on burying him upstate and drive to Tommy's mother's house to retrieve the tools needed to do so. As it turns out, Tommy's mother is awake and insists that the three men have a night-time meal before departing. Afterward, while on the road, they discover Batts is still agitating in the trunk; Tommy accordingly stabs him multiple times with a butcher knife he borrowed from his mother, and Jimmy then finishes him off by shooting him four times. They manage to bury Batts in the intended area, but six months later Jimmy learns that the burial spot will be the site of a new property development. Thus, they are forced to exhume Batts' half-decomposed corpse and move it to another location.

Tommy’s quick temper is shown on other occasions, even within their crew. One night, he attempts to provoke a young helper named Michael "Spider" Gianco (played by the then-unknown Michael Imperioli). Tommy takes out his pistol and gratuitously shoots Spider in the foot. Shortly thereafter, as Spider is recovering from his wound, Tommy again provokes him, asking him to dance on his wounded foot. However, Spider surprisingly stands up to Tommy. After Jimmy razzes Tommy regarding the young man’s gumption, Tommy instantly shoots the young man to death.

Violence also begins to invade Henry’s home life. He begins seeing a mistress named Janice Rossi (Gina Mastrogiacomo), and Karen soon finds out about the affair. She wakes him up one night, sitting on top of him with one of his guns pointed at his face, and angrily asks him whether he loves Rossi. A shocked yet confident Henry repeatedly tells Karen that he only loves his wife, until Karen breaks into tears and Henry violently subdues her onto the carpet floor. He in turn threatens her with the gun, saying that he already has enough problems to worry about, such as the possibility of being killed on the streets.

Soon, it gets harder for Henry to evade the law. Paulie sends him and Jimmy to collect from an indebted Florida gambler in Tampa, and they hang him in the lion's den at a public zoo to intimidate him further after a beating fails to sway the man. Henry, Jimmy, the gambler, and most of the crew (except for Tommy) are then arrested thanks to the gambler's sister, who is a typist for the FBI. They get a 10-year sentence in Federal Penitentiary. However, prison for the mobsters proves to be not that different than having their own small house, with free food and drinks. Henry makes drug deals in prison to support his family on the outside, and when he gets out, the crew commits the infamous Lufthansa Heist at John F. Kennedy International Airport.

Even after the successful heist, things begin to shake up even more. The crew members buy lavish gifts for their girlfriends, wives, and families from their share of the stolen money, flaunting them in public. Out of fear of being traced, Jimmy orders anyone involved in the heist to be killed one by one. In the meantime, Henry further establishes himself in the drug trade after seeing its high value, and convinces Tommy and Jimmy to join him.

Tommy is then deceived into thinking that he is going to become a made man. He is instead righteously executed by the Gambino crime family for Billy Batts' murder. Jimmy is devastated by the death of his protege, and anguished at the fact that there is nothing he can do about it. As Jimmy is of full Irish extraction, and Henry is half-Irish, neither of them are eligible to become made men. Hence, Tommy's formal induction into the Mafia was a source of pride, especially for Jimmy.

On Sunday, May 11, 1980, Henry needs to make a big criminal deal with associates in Atlanta. He drives all over town, busy getting his brother from the hospital and cooking food for the family, and is a nervous wreck from lack of sleep and the amount of cocaine he has taken. He is finally caught by narc agents and is sent to jail. Karen puts her mother's house up for bail to get him out. When he returns home, Karen tells him that she has flushed what amounted to $60,000 worth of cocaine down the toilet to prevent the FBI agents from finding it during their raid. As a result, Henry and his family are left virtually penniless.

Henry soon is excluded by Paulie for lying to him about his involvement in the drug trade, and becomes a mole for the FBI while in the Witness Protection Program to protect himself and his family. Henry is motivated to turn state's evidence when he learns that Paulie and Jimmy have set a trap for him in Florida. Although he is clearly thankful for escaping the mafia alive, he says that he will miss the life of organized crime, and laments the fact that he will now have to live a law-abiding life. Or as he puts it, "I get to live the rest of my life as a schnook.”

Title cards shown before the closing credits state that Henry returned to narcotics dealing but cleaned himself up, Paul Cicero died in 1988 in prison, and Jimmy Conway (at the time of the film's release) was serving 20 years-to-life in a New York State prison and would not be eligible for parole until 2004 (although he died in 1996 of lung cancer).

Cast

| Actor | Role | Based on |

|---|---|---|

| Ray Liotta | Henry Hill | Henry Hill |

| Robert De Niro | Jimmy Conway | Jimmy Burke |

| Joe Pesci | Tommy DeVito | Tommy DeSimone |

| Lorraine Bracco | Karen Hill | Karen Hill (née Friedman) |

| Paul Sorvino | Paul Cicero | Paul Vario |

| Chuck Low | Morrie Kessler | Martin Krugman |

| Frank DiLeo | Tuddy Cicero | Vito "Tuddy" Vario |

| Frank Sivero | Frankie Carbone | Angelo Sepe |

| Johnny Williams | Johnny Roastbeef | Louis Cafora |

| Mike Starr | Frenchy | Robert McMahon |

| Frank Vincent | Billy Batts | William "Billy Batts" DeVino |

| Jim Colella | Jim Colella | Jim Colella |

| Samuel L. Jackson | "Stacks" Edwards | Parnell Steven "Stacks" Edwards |

| Frank Adonis | Anthony Stabile | Anthony Stabile |

| Catherine Scorsese | Tommy DeVito's Mother | Thomas DeSimone's Grandmother |

| Gina Mastrogiacomo | Janice Rossi | Linda Coppociano |

| Debi Mazar | Sandy | Megan Cooperman |

| Margo Winkler | Belle Kessler | Fran Krugman |

| Welker White | Lois Byrd | Judy Wicks |

| Julie Garfield | Mickey Conway | Mickey Burke |

| Detective Ed Deacy | Himself | Himself |

| Christopher Serrone | Henry Hill (Youth) | Henry Hill (Youth) |

| Charles Scorsese | Vinnie | Thomas Agro |

| Michael Vivalo | Nicky Eyes | Himself |

| Wyatt A. O'brien | "Spider" | Michael "Spider" Gianco |

| Tony Darrow | Sonny Bunz | Angelo McConnach |

| Tony Ellis | Bridal Shop Owner | Jerome Asaro |

| Elizabeth Whitcraft | Tommy's Girlfriend at the Copa | Theresa Ferrara |

| Anthony Powers | Jimmy Two Times | Bobby "The Dentist" |

| U.S. Attorney Ed McDonald | Himself | Himself |

Development

Goodfellas is based on New York crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi's book Wiseguy. Martin Scorsese never intended to make another mob film until he read a review of the book and this inspired him to read it[1] while working on the set of Color of Money in 1986.[2] He had always been fascinated by the Mob lifestyle and was drawn to Pileggi's book because it was the most honest portrayal of gangsters he had ever read.[3] After he read Pileggi's book, the filmmaker knew what approach he wanted to take: "To begin Goodfellas like a gunshot and have it get faster from there, almost like a two-and-a-half-hour trailer. I think it's the only way you can really sense the exhilaration of the lifestyle, and to get a sense of why a lot of people are attracted to it."[4] According to Pileggi, Scorsese cold-called the writer and told him, "I've been waiting for this book my entire life." To which Pileggi replied "I've been waiting for this phone call my entire life".[5]

Scorsese originally intended to direct the film before The Last Temptation of Christ, but when funds materialized to make Last Temptation, he decided to postpone Wise Guy. He was drawn to the documentary aspects of Pileggi's book. "The book Wise Guys gives you a sense of the day-to-day life, the tedium - how they work, how they take over certain nightclubs, and for what reasons. It shows how it's done".[5] He saw Goodfellas as the third film in an unplanned trilogy of films that examined the lives of Italian-Americans "from slightly different angles".[6] He has often described the film as "a mob home movie" that is about money because "that's what they're really in business for".[3]

Screenplay

Scorsese and Pileggi collaborated on the screenplay and over the course of the 12 drafts it took to reach the ideal script, the reporter realized that "the visual styling had to be completely redone . . . So we decided to share credit".[5] They decided which sections of the book they liked and put them together like building blocks.[7] Scorsese persuaded Pileggi that they did not need to follow a traditional narrative structure. The director wanted to take the gangster film and deal with it episode by episode but start in the middle and move backwards and forwards. Scorsese would compact scenes and realized that if they were kept short, "the impact after about an hour and a half would be terrific".[7] He wanted to do the voiceover like the opening of Jules and Jim and use "all the basic tricks of the New Wave from around 1961".[7] Since the title of Pileggi's book had already been used for a TV series and for Brian De Palma's 1986 comedy Wise Guys, Pileggi and Scorsese decided to change the name of their film to Goodfellas.[7]

Casting

Once Robert De Niro agreed to play Conway, Scorsese was able to secure the money needed to make the film.[2] The director cast Ray Liotta after De Niro saw him in Jonathan Demme's Something Wild and Scorsese was surprised by "his explosive energy" in that film.[6] The actor had read Pileggi's book when it came out and was fascinated by it. A couple of years afterwards, his agent told him that Scorsese was going to direct a film version. In 1988, Liotta met the director over a period of a couple of months and auditioned for the film.[3] The actor campaigned aggressively for a role in the film but the studio wanted a well-known actor. "I think they would've rather had Eddie Murphy than me", the actor remembers.[8]

To prepare for the role, De Niro consulted with Pileggi who had research material that had been discarded while writing the book.[9] De Niro often called Hill several times a day to ask how Burke walked, held his cigarette, and so on.[10][11] Driving to and from the set, Liotta listened to FBI audio cassette tapes of Hill, so he could practice speaking like his real-life counterpart.[11] To research her role, Lorraine Bracco tried to get close to a Mob wife but was unable to because they exist in a very tight-knit community. She decided not to meet the real Karen because she "thought it would be better if the creation came from me. I used her life with her parents as an emotional guideline for the role".[12] Paul Sorvino had no problem finding the voice and walk of his character but found it challenging finding "that kernel of coldness and absolute hardness that is antithetical to my nature except when my family is threatened".[13]

Principal photography

The film was shot on location between Queens, New York and New Jersey during the spring and summer of 1989. [14] Scorsese broke the film down into sequences and storyboarded everything because of the complicated style throughout. According to the filmmaker, he "wanted lots of movement and I wanted it to be throughout the whole picture, and I wanted the style to kind of break down by the end, so that by his [Henry] last day as a wiseguy, it's as if the whole picture would be out of control, give the impression he's just going to spin off the edge and fly out."[1] He claims that the film's style comes from the first two or three minutes of Jules and Jim: extensive narration, quick edits, freeze frames, and multiple locale switches.[4] It was this reckless attitude towards convention that mirrored the attitude of many of the gangsters in the film. Scorsese remarked, "So if you do the movie, you say, 'I don't care if there's too much narration. Too many quick cuts? - That's too bad.' It's that kind of really punk attitude we're trying to show".[4] He adopted a frenetic style in order to almost overwhelm the audience with images and information.[7] He also put a lot of detail in every frame because the gangster life is so rich. The use of freeze frames was done because Scorsese wanted images that would stop "because a point was being reached" in Henry's life.[7]

Joe Pesci did not judge his character but found the scene where he kills Spider for talking back to his character hard to do because he had trouble justifying the action until he forced himself to feel the way Tommy did.[3] Lorraine Bracco found the shoot to be an emotionally difficult one because it was such a male-dominated cast and realized that if she did not make her "work important, it would probably end up on the cutting room floor".[3] When it came to the relationship between Henry and Karen, Bracco saw no difference between an abused wife and her character.[3]

According to Pesci, improvisation and ad-libbing came out of rehearsals where Scorsese let the actors do whatever they wanted. He made transcripts of these sessions, took the lines that the actors came up with that he liked best, and put them into a revised script that the cast worked from during principal photography.[9] For example, in the scene where Tommy tells the story and Henry is responding to him - the "what's so funny about me" scene, was based on actual event that happened to Pesci. It was worked on in rehearsals where he and Liotta improvised and Scorsese recorded 4-5 takes, rewrote their dialogue and inserted it into the script.[15] The cast did not meet Henry Hill during the film's shoot but a few weeks before it premiered, Liotta met him in an undisclosed city. Hill had seen the film and told the actor that he loved it.[3]

The long tracking shot through the Copacabana nightclub came about because of a practical problem - the filmmakers could not get permission to go in the short way and this forced them to go round the back.[7] Scorsese decided to do it in one shot in order to symbolize Henry's whole life is ahead of him and according to the director, "It's his seduction of her [Karen] and it's also the lifestyle seducing him".[7] This sequence was shot eight times.[15] Henry's last day as a wiseguy was the hardest part of the film for Scorsese to shoot because he wanted to create the character's state of anxiety and the way the mind races when on drugs for people who had never been under the influence of cocaine and amphetamines.[7] The director ended the film with Henry regretting that he is no longer a wiseguy and Scorsese said, "I think the audience should get angry at him and I would hope they do - and maybe with the system which allows this".[7]

Post-production

Scorsese wanted to depict the film's violence realistically, "cold, unfeeling and horrible. Almost incidental."[2] However, he had to remove ten frames of blood in order to ensure an R rating from the MPAA.[6] With a budget of $25 million, Goodfellas was Scorsese's most expensive film to date but still only a medium budget by Hollywood standards.[7] It was also the first time he was obliged by Warner Bros. to preview the film. It was shown twice in California and a lot of audiences were "agitated" by Henry's last day as a wise guy sequence and Scorsese argued that that was the point of the scene.[7] Scorsese and the film's editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, made this sequence faster with more jump cuts to convey Henry's drug-addled point of view. In the first test screening there were 40 walkouts in the first ten minutes.[15] One of the favorite scenes for test audiences was the one where Tommy tells the story and Henry is responding to him - the "what's so funny about me" scene.[7]

Soundtrack

Scorsese chose the songs for Goodfellas only if they commented on the scene or the characters "in an oblique way".[6] The only rule he adhered to with the soundtrack was to only use music that could have been heard at that time.[7] For example, if a scene took place in 1973, he could use any song that was current or older. According to Scorsese, a lot of non-dialogue scenes were shot to playback. For example, he had "Layla" playing on the set while shooting the scene where the dead bodies are discovered in the car and the meat-truck.[7] Sometimes, the lyrics of songs were put between lines of dialogue to comment on the action.[7] Some of the music Scorsese had written into the script while other songs he discovered during the editing phase.[15]

Network TV version

The dubbing of the dialogue of the network TV version was personally directed by Scorsese himself. It added a personal introduction to the film from Scorsese himself. It contains frequent usage of variants of the word "freak", such as "I've got this freakin' gun pointed at your freakin' head." However, much other profanity in the film was retained, as was the violence.[16]

Reception

Distribution

Goodfellas has its world premiere at the 1990 Venice Film Festival where Scorsese received the Silver Lion award for Best Director.[17] It was given a wide release in North America on September 21, 1990 in 1,070 theaters with an opening weekend gross of USD $6.3 million. It went on to make $46.8 million domestically, well above its $25 million budget.[18]

The film received mostly positive reviews from critics and currently has a 96% rating at Rotten Tomatoes and a 89 metascore at Metacritic. In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, "More than any earlier Scorsese film, Goodfellas is memorable for the ensemble nature of the performances . . . The movie has been beautifully cast from the leading roles to the bits. There is flash also in some of Mr. Scorsese's directorial choices, including freeze frames, fast-cutting and the occasional long tracking shot. None of it is superfluous".[19] USA Today gave the film four out of four stars and called it, "great cinema - and also a whopping good time".[4] David Ansen, in his review for Newsweek magazine, wrote "Every crisp minute of this long, teeming movie vibrates with outlaw energy".[20] However, Anthony Lane in the The Independent wrote, "There is a short, needling comedy of violence and cowardice somewhere inside this stylish film, and it is worth watching more than once to prise it free. Scorsese himself chickened out, I think; perhaps the Mob got to him after all".[21] William Fugazy, of the National Ethnic Coalition of Organizations, a watchdog group on ethnic injustice, which claims a membership of 10 million and consists of 76 of the largest heritage groups in the United States, called for a boycott of the film and wanted Warner Bros. to ban it. "It's the worst stereotyping, the worst portrayal of the Italian community I've ever seen. Far worse than The Godfather. One killing after another", he said.[22] Scorsese responded to this criticism by saying, "As Nick Pileggi always points out, there are 18 to 20 million Italian-Americans. Out of that, there are only 4,000 alleged organised crime members. But, as Nick says, they cast a very long shadow".[7]

Awards

Goodfellas was nominated for six Academy Awards including Joe Pesci for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, Lorraine Bracco for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Best Picture, Scorsese for Best Director, Thelma Schoonmaker for Best Film Editing, and Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi for Best Adapted Screenplay.[23] When Joe Pesci won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor (the only Academy Award the film won),[24] his entire speech was "This is an honor and a privilege, thank you".[25] It is the third shortest Oscar-acceptance speech, after William Holden's, who simply said, "Thank you", upon winning for Stalag 17, and Alfred Hitchcock's, who merely said, "Thanks," when he received an Honorary Oscar. Later, Pesci admitted that he did not say more, because "I really didn't think I was going to win".[25]

Goodfellas was nominated for five Golden Globes including Best Director, Best Motion Pictures, Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actress, and Best Screenplay.[26] It failed to win any of these awards. Scorsese's film won three awards from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts including Best Film, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay.[27]

The New York Film Critics Circle voted Goodfellas the Best Film of 1990, Robert De Niro was named Best Actor for his performance in the film and in Awakenings, and Scorsese was voted Best Director.[28] The Los Angeles Film Critics Association also voted Scorsese as Best Director, GoodFellas as Best Film,[28] awards for Pesci and Bracco as Best Supporting Actor and Actress, respectively, and Best Cinematography to Michael Ballhaus for his work on the film.[29] The National Board of Review voted Pesci as Best Supporting Actor.[30] The National Society of Film Critics voted Goodfellas Best Film of 1990 and Scorsese as Best Director.[31] American Film magazine declared Goodfellas the best film of 1990 according to a poll of 80 movie critics.[32]

Legacy

GoodFellas is #94 on the American Film Institute's list of 100 Years, 100 Movies and #92 on its updated version from 2007. In June 2008, the AFI revealed its "Ten top Ten"—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Goodfellas was acknowledged as the second best in the gangster film genre (after the Godfather).[33] In 2000, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. It is one of the only five films to make the Registry in its first year of eligibility.

Roger Ebert, a friend and supporter of Scorsese, named GoodFellas the "best mob movie ever" and placed it among the best films of the nineties.[34] Premiere magazine listed Joe Pesci as #96 on its list of The 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All Time, calling him "perhaps the single most irredeemable character ever put on film".[35] Channel 4 placed Goodfellas at #10 in their 2002 poll The 100 Greatest Films. In 2005, Total Film, named GoodFellas as the greatest film of all time. In December 2002, a UK film critics poll in Sight and Sound ranked the film #4 on their list of the 10 Best Films of the Last 25 Years.[36] Empire magazine ranked Tommy DeVito #59 in their "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters" poll.[37]

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #94

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #92

- AFI's 10 Top 10 #2 Gangster

References

Notes

- ^ a b Malcolm, Derek (September/October 1990). "Made Men". Film Comment.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Goodwin, Richard. "The Making of Goodfellas". Hotdog.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Linfield, Susan (September 16, 1990). "Goodfellas Looks at the Banality of Mob Life". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Clark, Mike (September 19, 1990). "GoodFellas step from his childhood". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Kelly, Mary Pat (March 2003). "Martin Scorsese: A Journey". Thunder Mouth Press.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Gilbert, Matthew (September 16, 1990). "Scorsese Tackles the Mob". Boston Globe.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Thompson, David (1996). "Scorsese on Scorsese". Faber and Faber. pp. 150–161.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Thompson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Portman, Jamie (October 1, 1990). "Goodfellas Star Prefers Quiet Life". Toronto Star.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Arnold, Gary (September 25, 1990). "Real Fellas Talk about Mob Film". Washington Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Wolf, Buck (November 8, 2005). "Rap Star 50 Cent Joins Movie Mobsters". ABC News. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Papamichael, Stella (October 22, 2004). "GoodFellas: Special Edition DVD (1990)". BBC. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Witchel, Alex (September 27, 1990). "A Mafia Wife Makes Lorraine Bracco a Princess". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (October 12, 1990). "At the Movies". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hughes, Howard Crime Wave: The Filmgoers' guide to the great crime movies p.177.

- ^ a b c d Kaplan, Jonah (2004). "Getting Made: The Making of Goodfellas". Goodfellas: Two-Disc Special Edition DVD. Warner Bros.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0099685/alternateversions

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (September 17, 1990). "The Venice Film Festival ends in uproar". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Goodfellas". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Canby, Vincent (September 19, 1990). "A Cold-Eyed Look at the Mob's Inner Workings". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ansen, David (September 17, 1990). "A Hollywood Crime Wave". Newsweek.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lane, Anthony (October 28, 1990). "The Mob gets to Scorsese". The Independent.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "U.S. Italians outraged by new Scorsese movie". Reuters. September 17, 1990.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "And the Oscar Nominees Are ...". Associated Press. February 14, 1991.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rohter, Larry (March 26, 1991). "Kevin Costner and Dances With Wolves Win Top Oscar Prizes". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Dhesi, Japinder (September 20, 2004). "Worst awards performances". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Godfather lands 7 Globe nominations". Toronto Star. December 28, 1990.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "GoodFellas, Cinema Paradiso dominate the British Oscars". Associated Press. March 18, 1991.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Spillman, Susan (December 19, 1990). "Critics join mob honoring GoodFellas". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Landis, David (December 17, 1990). "Ganging up to praise GoodFellas". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Spillman, Susan (December 14, 1990). "Wolves dances away with award". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fox, David J (January 8, 1991). "Critics say they're jolly GoodFellas". Toronto Star.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Arnold, Gary (February 19, 1991). "GoodFellas targeted for even more acclaim". Washington Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Best Films of the '90s". Ebert & Roeper. February 27, 2000. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All Time". Premiere. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Modern Times". Sight and Sound. December 2002. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Bibliography

- Martin Scorsese: A Journey, by Mary Pat Kelly (2003, Thunder Mouth Press), ISBN 978-1560254706.

- Scorsese on Scorsese, by David Thompson and Ian Christie (2004, Faber and Faber), ISBN 978-0571220021.

- Goodfellas, by Nicholas Pileggi and Martin Scorsese (1990, Faber and Faber), ISBN 978-0571162659.

- Wiseguy, by Nicholas Pileggi (1990, Rei Mti), ISBN 978-0671723224.

External links

- Goodfellas at IMDb

- Goodfellas at AllMovie

- Goodfellas at Rotten Tomatoes

- Goodfellas at Metacritic

- Goodfellas at Box Office Mojo

- Reel Faces: Fact vs. Fiction

- 1990 films

- American drama films

- Biographical films

- English-language films

- Films based on actual events

- 1990s crime films

- 1990s drama films

- Films directed by Martin Scorsese

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winning performance

- Films shot in Super 35

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in the 1970s

- Films set in the 1980s

- Italian-language films

- Lucchese crime family

- Mafia films

- Crime drama films

- Drug-related films

- Gangster films

- True crime films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films set in Brooklyn