Pub: Difference between revisions

Kbthompson (talk | contribs) Undid revision 276140648 by 131.227.223.163 (talk) - rv gf - if money changes hands, they're open! |

→Notes: new reference |

||

| Line 299: | Line 299: | ||

===Notes=== |

===Notes=== |

||

{{Reflist|2}} |

{{Reflist|2}} |

||

Trade Signs of Essex by Miller Christie pub 1887.<ref name="trade signs">[http://www.essex-family-history.co.uk/pubsigns.htm Link text], </ref> |

|||

===Bibliography=== |

===Bibliography=== |

||

*''Beer and Britannia: An Inebriated History of Britain'', Peter Haydon, Sutton (2001) |

*''Beer and Britannia: An Inebriated History of Britain'', Peter Haydon, Sutton (2001) |

||

Revision as of 01:06, 13 March 2009

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

A public house, the formal name for a pub in Britain, is a drinking establishment licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on or off the premises in countries and regions of British influence.[1][2] Although the terms often have different connotations, there is little definitive difference between pubs, bars, inns, taverns and lounges where alcohol is served commercially. A pub that offers lodging may be called an inn or (more recently) hotel in the UK. Today many pubs in the UK, Canada and Australia with the word "inn" or "hotel" in their name no longer offer accommodation, or in some cases have never done so. Some pubs bear the name of "hotel" because they are in countries where stringent anti-drinking laws were once in force. In Scotland until 1976, only hotels could serve alcohol on Sundays.[3]

Overview

There are approximately 57,500[4] public houses in the United Kingdom, with at least one in almost every city, town and village. In many places, especially in villages, a pub can be the focal point of the community, playing a complementary role to the local church in this respect. The writings of Samuel Pepys describe the pub as the heart of England and the church as its soul.

Public houses are culturally and socially different from places such as cafés, bars, bierkellers and brewpubs.

Pubs are social places based on the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, and most public houses offer a range of beers, wines, spirits, alcopops and soft drinks. Many pubs are controlled by breweries, so beer is often better value than wines and spirits, while soft drinks can be almost as expensive. Beer served in a pub may be cask ale or keg beer. All pubs also have a range of non-alcoholic beverages available. Traditionally the windows of town pubs are of smoked or frosted glass so that the clientèle is obscured from the street. In the last twenty years in the UK and other countries there has been a move away from frosted glass towards clear glass, a trend that fits in with brighter interior décors.

The owner, tenant or manager (licensee) of a public house is known as the publican or landlord. Each pub generally has "locals" or regulars; people who drink there regularly. The pub that people visit most often is called their local. In many cases, this will be the pub nearest to their home, but some people choose their local for other reasons: proximity to work, a venue for their friends, the availability of a particular cask ale, non-smoking or formerly as a place to smoke freely, or maybe a darts team or pool table.

Until the 1970s most of the larger public houses also featured an off-sales counter or attached shop for the sales of beers, wines and spirits for home consumption. In the 1970s the newly built supermarkets and high street chain stores or off-licences undercut the pub prices to such a degree that within ten short years all but a handful of pubs had closed their off-sale counters.

A society with a particular interest in British beers, ales and the preservation of the 'integrity' of the public house is Campaign for Real Ale, (CAMRA).

Another organisation, lauched in Dorset (initially) in 2009 is Community Alert on Pubs which seeks to prevent the closure of pubs which form part of the rural social fabric.[5]. A particular concern has been the practice of closing a pub and leaving it derelict as an eyesore until such time as the local authority may (or may not) grant a change of use e.g. for residential property development.

History

The inhabitants of the UK have been drinking ale since the Bronze Age, but it was with the arrival of the Romans and the establishment of the Roman road network that the first Inns called tabernae,[6] in which the traveller could obtain refreshment, began to appear. By the time the Romans had left, the Anglo-Saxons had formed alehouses that grew out of domestic dwellings. The Saxon alewife would put a green bush up on a pole to let people know her brew was ready.[7] These alehouses formed meeting houses for the locals to meet and gossip and arrange mutual help within their communities. Here lies the beginnings of the modern pub. They became so commonplace that in 965 King Edgar decreed that there should be no more than one alehouse per village.

A traveller in the early Middle Ages could obtain overnight accommodation in monasteries, but later a demand for hostelries grew with the popularity of pilgrimages and travel. The Hostellers of London were granted guild status in 1446 and in 1514 the guild became the Worshipful Company of Innholders.[8]

Traditional English ale was made solely from fermented malt. The practice of adding hops to produce beer was introduced from the Netherlands in the early 15th century. Alehouses would each brew their own distinctive ale, but independent breweries began to appear in the late 17th century. By the end of the century almost all beer was brewed by commercial breweries.

The 18th century saw a huge growth in the number of drinking establishments, primarily due to the introduction of gin. Gin was brought to England by the Dutch after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and started to become very popular after the government created a market for grain that was unfit to be used in brewing by allowing unlicensed gin production, whilst imposing a heavy duty on all imported spirits. As thousands of gin-shops sprang up all over England, brewers fought back by increasing the number of alehouses. By 1740 the production of gin had increased to six times that of beer and because of its cheapness it became popular with the poor, leading to the so-called Gin Craze. Over half of the 15,000 drinking establishments in London were gin-shops.

The drunkenness and lawlessness created by gin was seen to lead to ruination and degradation of the working classes. The distinction was illustrated by William Hogarth in his engravings Beer Street and Gin Lane.[9] The Gin Act (1736) imposed high taxes on retailers but led to riots in the streets. The prohibitive duty was gradually reduced and finally abolished in 1742. The 1751 Gin Act however was more successful. It forced distillers to sell only to licensed retailers and brought gin-shops under the jurisdiction of local magistrates.

Beer Houses and the 1830 Beer Act

By the early 1800s and encouraged by a lowering of duties on gin, the gin houses or “Gin Palaces” had spread from London to most major cities and towns in Britain, with most of the new establishments illegal and unlicensed. These bawdy, loud and unruly drinking dens so often described by Charles Dickens in his Sketches by Boz (published 1835–6) increasingly came to be held as unbridled cesspits of immorality or crime and the source of much ill-health and alcoholism among the working classes.[10]

The British government’s eventual response to the problem seems strange now to modern eyes. Under a banner of “reducing public drunkenness” the Beer Act of 1830 introduced a new lower tier of premises permitted to sell alcohol, the Beer Houses. At the time beer was viewed as harmless, nutritious and even healthy. Young children were often given what was described as small beer, which was brewed to have a low alcohol content, to drink, as the local water was often unsafe. Even the evangelical church and temperance movements of the day viewed the drinking of beer very much as a secondary evil and a normal accompaniment to a meal. The freely available beer was thus intended to wean the drinkers off the evils of gin, or so the thinking went.[11]

Under the 1830 Act any householder who paid rates could apply, with a one-off payment of two guineas, to sell beer or cider in his home (usually the front parlour) and even brew his own on his premises. The permission did not extend to the sale of spirits and fortified wines and any beer house discovered selling those items were closed down and the owner heavily fined. Beer houses were not permitted to open on Sundays. The beer was usually served in jugs or dispensed direct from tapped wooden barrels lying on a table in the corner of the room. Often profits were so high the owners were able to buy the house next door to live in, turning every room in their former home into bars and lounges for customers.

In the first year four hundred beer houses opened but within eight years there were 46,000[12] opened across the country, far outnumbering the combined total of long established taverns, public houses, inns and hotels. Because it was so easy to obtain permission and the profits could be huge compared to the low cost of gaining permission, the number of beer houses was continuing to rise and in some towns nearly every other house in a street could be a Beer House. Finally in 1869 the growth had to be checked by magisterial control and new licensing laws were introduced. Only then was the ease by which permission could be obtained reduced and the licensing laws which operate today formulated.

Although the new licensing laws prevented any new beer houses from being created, those already in existence were allowed to continue and many did not fully die out until nearly the end of the 19th century. A vast majority of the beer houses applied for the new licences and became full public houses. These usually small establishments can still be identified in many towns, seemingly oddly located in the middle of otherwise terraced housing part way up a street, unlike purpose built pubs that are usually found on corners or road junctions. Many of today's respected real ale micro-brewers in the UK started as home based Beer House brewers under the 1830 Act.

The beer houses also tended to avoid the traditional public house names like The Crown, The Red Lion, The Royal Oak etc and, if they didn’t simply name their place Smith’s Beer House, they would apply topical pub names in an effort to reflect the mood of the times.

Licensing laws

From the middle of the 19th century restrictions were placed on the opening hours of licensed premises in the UK. However licensing was gradually liberalised after the 1960s, until contested licensing applications became very rare, and the remaining administrative function was transferred to Local Authorities in 2005.

The Wine and Beerhouse Act 1869 reintroduced the stricter controls of the previous century. The sale of beers, wines or spirits required a licence for the premises from the local magistrates. Further provisions regulated gaming, drunkenness, prostitution and undesirable conduct on licensed premises, enforceable by prosecution or more effectively by the landlord under threat of forfeiting his licence. Licences were only granted, transferred or renewed at special Licensing Sessions courts, and were limited to respectable individuals. Often these were ex-servicemen or ex-policemen; retiring to run a pub was popular amongst military officers at the end of their service. Licence conditions varied widely, according to local practice. They would specify permitted hours, which might require Sunday closing, or conversely permit all-night opening near a market. Typically they might require opening throughout the permitted hours, and the provision of food or lavatories. Once obtained, licences were jealously protected by the licensees (always individuals expected to be generally present, not a remote owner or company), and even "Occasional Licences" to serve drinks at temporary premises such as fêtes would usually be granted only to existing licensees. Objections might be made by the police, rival landlords or anyone else on the grounds of infractions such as serving drunks, disorderly or dirty premises, or ignoring permitted hours.

Detailed records were kept on licensing, giving the Public House, its address, owner, licensee and misdemeanours of the licensees for periods often going back for hundreds of years. Many of these records survive and can be viewed, for example, at the London Metropolitan Archives centre.

These culminated in the Defence of the Realm Act[13] of August 1914, which, along with the introduction of rationing and the censorship of the press for wartime purposes, also restricted the opening hours of public houses to 12noon–2.30pm and 6.30pm–9.30pm. Opening for the full licensed hours was compulsory, and closing time was equally firmly enforced by the police; a landlord might lose his licence for infractions. There was a special case established under the State Management Scheme[14] where the brewery and licensed premises were bought and run by the state until 1973, most notably in the Carlisle District. During the 20th century elsewhere, both the licensing laws and enforcement were progressively relaxed, and there were differences between parishes; in the 1960s, at closing time in Kensington at 10.30 pm, drinkers would rush over the parish boundary to be in good time for "Last Orders" in Knightsbridge before 11 pm, a practice observed in many pubs adjoining licensing area boundaries. Some Scottish and Welsh parishes remained officially "dry" on Sundays (although often this merely required knocking at the back door of the pub).

However, closing times were increasingly disregarded in the country pubs. In England and Wales by 2000 pubs could legally open from 11am (12 noon on Sundays) through to 11pm (10.30pm on Sundays). That year was also the first to allow continuous opening for 36 hours from 11am on New Year's Eve to 11pm on New Year's Day. In addition, many cities had by-laws to allow some pubs to extend opening hours to midnight or 1am, whilst nightclubs had long been granted late licences to serve alcohol into the morning. Pubs in the immediate vicinity of London's Smithfield market, Billingsgate fish market and Covent Garden fruit and flower market were permitted to stay open 24 hours a day since Victorian era times to provide a service to the shift working employees of the markets. These restricted opening hours led to the tradition of lock-ins.

Scotland's and Northern Ireland's licensing laws have long been more flexible, allowing local authorities to set pub opening and closing times. In Scotland, this stemmed out of a late repeal of the wartime licensing laws, which stayed in force until 1976.

The Licensing Act 2003[15], which came into force on November 24, 2005, aimed to consolidate the many laws into a single act. This now allows pubs in England and Wales to apply to the local authority for opening hours of their choice. Supporters at the time argued that it would end the concentration of violence around half past 11, when people had to leave the pub, making policing easier. In practice, alcohol-related hospital admissions rose following the change in the law, with alcohol involved in 207,800 admissions in 2006/7.[16] Critics claimed that these laws will lead to '24-hour drinking'. By the day before the law came into force, 60,326 establishments had applied for longer hours, and 1,121 had applied for a licence to sell alcohol 24 hours a day. However, nine months after the act many pubs had not changed their hours, although there is a growing tendency for some to be open longer at the weekend but rarely beyond 1:00 am.

Indoor smoking ban

In July 2007, a law was introduced to forbid smoking in all enclosed public places in England and Wales. Scotland had introduced the ban in April 2006.[17] Concerns by publicans prior to the ban that a smoking ban would have a negative impact on sales appear to have come true with Wetherspoons reporting a 16% fall in profits,[18] and Scottish & Newcastle's take over by Carlsberg and Heineken being reported as partly the result of its weakness following falling sales due to the ban.[19]

To accommodate the remaining smokers, most pubs which have the space have provided outdoor facilities. These can range from a simple picnic bench table with a parasol umbrella in the garden or carpark, to a purpose built brick lean-to with a tiled roof. The law states that the facility must be open on at least one side and cannot be in an area where nonsmokers have to pass while entering or leaving the pub premises. Country pubs with plenty of space and beer gardens have adapted to the changes reasonably easily, but smaller city centre pubs on the pavement edge and with no rear gardens have suffered significant losses of custom by not being able to provide a suitable smoking area.

Pub Architecture

The saloon or lounge

By the end of the 18th century a new room in the pub was established: the saloon. Beer establishments had always provided entertainment of some sort — singing, gaming or a sport. Balls Pond Road in Islington was named after an establishment run by a Mr. Ball that had a pond at the rear filled with ducks, where drinkers could, for a certain fee, go out and take a potshot at shooting the fowl. More common, however, was a card room or a billiards room. The saloon was a room where for an admission fee or a higher price of drinks, singing, dancing, drama or comedy was performed and drinks would be served at your table. From this came the popular music hall form of entertainment—a show consisting of a variety of acts. A most famous London saloon was the Grecian Saloon in The Eagle, City Road, which is still famous these days because of an English nursery rhyme: "Up and down the City Road / In and out The Eagle / That's the way the money goes / Pop goes the weasel.". The implication being that, having frequented the Eagle public house, the customer spent all his money, and thus needed to 'pawn' his 'weasel' to get some more. The exact definition of the 'weasel' is unclear but the two most likely definitions are: that a weasel is a flat iron used for finishing clothing; or that 'weasel' is rhyming slang for a coat (weasel and stoat).[20]

A few pubs have stage performances, such as serious drama, stand-up comedians, a musical band or striptease; however juke boxes and other forms pre-recorded music have otherwise replaced the musical tradition of a piano and singing.

The public bar

By the 20th century, the saloon, or lounge bar, had settled into a middle-class room — carpets on the floor, cushions on the seats, and a penny or two on the prices, while the public bar, or tap room, remained working class with bare boards, sometimes with sawdust to absorb the spitting and spillages, hard bench seats, and cheap beer.

Later, the public bars gradually improved until sometimes almost the only difference was in the prices, so that customers could choose between economy and exclusivity (or youth and age, or a jukebox or dartboard). During the blurring of the class divisions in the 1960s and 1970s, the distinction between the saloon and the public bar was often seen as archaic, and was frequently abolished, usually by the removal of the dividing wall or partition itself. While the names of saloon and public bar may still be seen on the doors of pubs, the prices (and often the standard of furnishings and decoration) are the same throughout the premises, and many pubs now comprise one large room. However, the modern importance of dining in pubs encourages some establishments to maintain distinct rooms or areas, especially where the building has the right characteristics for this. Yet, in a few pubs there still remain rooms or seats that, by local custom, "belong" to particular customers.

However there still remain a few, mainly city centre pubs, that retain a public bar mainly for working men that call in for a drink while still dressed in working clothes and dirty boots. They are now very much in a minority, but some landlords prefer to separate the manual workers from the more smartly dressed businessmen or diners in the lounge or restaurant.

The snug

The "snug", also sometimes called the Smoke room, was typically a small, very private room with access to the bar that had a frosted glass external window, set above head height. You paid a higher price for your beer in the Snug, but nobody could look in and see you. It was not only the well off visitors who would use these rooms. The snug was for patrons who preferred not to be seen in the public bar. Ladies would often enjoy a private drink in the snug in a time when it was frowned upon for ladies to be in a pub. The local police officer would nip in for a quiet pint, the parish priest for his evening whisky, and lovers would use the snug for their clandestine visits.

The counter

It was the public house that first introduced the concept of the bar counter being used to serve the beer. Until that time beer establishments used to bring the beer out to the table or benches. A bar might be provided for the manager to do his paperwork whilst keeping an eye on his customers, but the casks of ale were kept in a separate taproom. When the first public houses were built, the main room was the public room with a large serving bar copied from the gin houses, the idea being to serve the maximum amount of people in the shortest possible time. It became known as the public bar. The other, more private, rooms had no serving bar - they had the beer brought to them from the public bar. There are a number of pubs in the Midlands or the North which still retain this set up. But these days you fetch the beer yourself from the taproom or public bar. The most famous of these is The Vine, known locally as The Bull & Bladder, in Brierley Hill near Birmingham.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the British engineer and railway builder, introduced the idea of a circular bar into the Swindon station pub in order that customers were served quickly and didn’t delay his trains. These island bars quickly became popular as they also allowed staff to serve customers in several different rooms surrounding the bar. In a modern renovated pub, where the partitions between rooms have been removed, the island can be clearly seen.

Beer engine

A "beer engine" is a device for pumping beer, originally manually operated and typically used to dispense beer from a cask or container in a pub's basement or cellar. It was invented by the locksmith and hydraulic engineer Joseph Bramah. Strictly the term refers to the pump itself, which is normally manually operated, though electrically powered and gas powered [21] pumps are occasionally used; when manually powered, the term "handpump" is often used to refer to both the pump and the associated handle.

Entertainment

Games and sports

Traditional games are played in pubs, ranging from the well-known darts[22], skittles[23], dominoes[24], cards and bar billiards[25], to the more obscure Aunt Sally[26], Nine Men's Morris[27] and ringing the bull[28]. Betting is legally limited to certain games such as cribbage or dominoes, but these are now rarely seen. In recent decades the game of pool[29] (both the British and American versions) has increased in popularity, other table based games such as snooker[30], Table Football are also common.

Increasingly, more modern games such as video games and slot machines are provided. Many pubs also hold special events, from tournaments of the aforementioned games to karaoke nights to pub quizzes. Some play pop music and hip-hop (dance bar), or show football and rugby union on big screen televisions (sports bar). Shove ha'penny[31] and Bat and trap[32] was also popular in pubs south of London.

Many pubs in the UK also have football teams composed of regular customers. Many of these teams are in leagues that play matches on Sundays, hence the term "Sunday League Football".

Music

While many pubs play piped pop music, the pub is often a venue for live song and live music. See:

- Pub rock - bands such as Kilburn and the High Roads, Dr. Feelgood or The Kursaal Flyers

- Pub songs from Skiffle to Danny Boy

- Folk music

The pub has also been celebrated in popular music. Examples are "Hurry Up Harry" by the 1970s punk rock act Sham 69, the chorus of which was the chant "We're going down the pub" repeated several times. Another such song is "Two Pints Of Lager and a Packet of Crisps Please!" by UK punk band Splodgenessabounds.

As a reaction against piped music, the Quiet Pub Guide was written, telling its readers where to go to avoid piped music.

Food

Traditionally pubs in England were drinking establishments and little emphasis was placed on the serving of food, usually called 'bar snacks', of which the usual fare consisted of specialised English snack food such as pork scratchings[33], pickled eggs, along with crisps and peanuts — salted snacks sold or given away to increase customers' thirst. If a pub served meals they were usually basic cold dishes such as a ploughman's lunch[34]. In South East England (especially London) it was common until recent times for vendors selling cockles, whelks, mussels and other shellfish, to sell to customers during the evening and at closing time. Many mobile shellfish stalls would set up near to popular pubs, a practice that continues in London's East End.

In the 1950s most British pubs would offer "a pie and a pint", with hot individual steak and ale pies made easily on the premises by the landlord's wife. In the 1960s and 1970s this developed into the then fashionable and universal "chicken in a basket", a portion of roast chicken with chips, served on a napkin, in a small wicker basket.

The offering in Irish pubs has always been a hearty experience, with fresh local food being offered. In less well-off times this would have been a stew and some fresh soda bread but today all over the world you can enjoy the best of food locally supplied.

Since the 1990s food has become more important as part of a pub's trade and today most pubs serve lunches and dinners at the table (colloquially this is known in England as pub grub)[33] in addition to (or instead of) snacks consumed at the bar. They may have a separate dining room. Some pubs serve excellent meals that can rival a good restaurant's. A pub that claims to focus on quality food (perhaps rather than necessarily on good beer) will now call itself a gastropub. The growth in importance of food, and the appeal of eating informally in a pub rather than with the formality expected in a restaurant, has led to some establishments giving all tables over to food and removing the bar stools (even though a visitor expecting a quick drink and a conversation at the bar is likely to receive short shrift at such places, there is no legal bar to such a licensed restaurant calling itself a pub).

Pub grub

"Pub grub" is food that is typically found in a pub. A British pub menu tends to include items such as beef and ale pie, steak and kidney pie, shepherd's pie, fish and chips, bangers and mash, hot pot, Sunday roast, ploughman's lunch, pasties. Some dishes that are quite specific to pubs include chicken or scampi in a basket, and meals served in plate-sized Yorkshire puddings. In addition, international dishes such as burgers, curry, lasagne and chilli con carne are often served.[35][36]

Typically pub food is ordered at the bar and paid for in advance. Customers traditionally seat themselves, and are often given a number, or a unique table marker, to assist the barstaff in delivering their food.

Gastropub

A gastropub is a pub which specialises in high-quality food a step above the more basic "pub grub." The name is a combination of pub and gastronomy and was coined in 1991 when David Eyre and Mike Belben opened a pub called The Eagle in Clerkenwell, London.[37] They placed emphasis on the quality of food served.

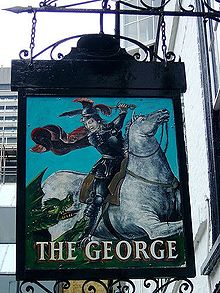

Signs

In 1393 King Richard II compelled landlords to erect signs outside their premises. The legislation stated "Whosoever shall brew ale in the town with intention of selling it must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale." This was in order to make them easily visible to passing inspectors, borough ale tasters, who would decide the quality of the ale they provided. William Shakespeare's father, John Shakespeare was one such inspector.

Another important factor was that during the Middle Ages a large percentage of the population would have been illiterate and so pictures on a sign were more useful than words as a means of identifying a public house. For this reason there was often no reason to write the establishment's name on the sign and inns opened without a formal written name—the name being derived later from the illustration on the public house's sign.

The earliest signs were often not painted but consisted, for example, of paraphernalia connected with the brewing process such as bunches of hops or brewing implements, which were suspended above the door of the public house. In some cases local nicknames, farming terms and puns were also used. Local events were also often commemorated in pub signs. Simple natural or religious symbols such as the 'The Sun', 'The Star' and 'The Cross' were also incorporated into pub signs, sometimes being adapted to incorporate elements of the heraldry (e.g. the coat of arms) of the local lords who owned the lands upon which the public house stood. Some pubs also have Latin inscriptions.

Other subjects that lent themselves to visual depiction included the name of battles (e.g. Trafalgar), explorers, local notables, discoveries, sporting heroes and members of the royal family. Some pub signs are in the form of a pictorial pun or rebus. For example, a pub in Crowborough, East Sussex called The Crow and Gate has an image of a crow with gates as wings.

Most British pubs still have decorated signs hanging over their doors, and these retain their original function of enabling the identification of the public house. Today's pub signs almost always bear the name of the pub, both in words and in pictorial representation. The more remote country pubs often have stand-alone signs directing potential customers to their door.

Names

Pubs often have traditional names. A very common name is the "Marquis of Granby". These pubs were named after John Manners, Marquess of Granby, who was the son of John Manners, 3rd Duke of Rutland) and a general in the 18th century British Army. He showed a great concern for the welfare of his men, and on their retirement, provided funds for many of them to establish taverns, which were subsequently named after him. The name may also have gained popularity because of the novel The Pickwick Papers. In that much-loved book, Charles Dickens depicted a character, Tony Weller, who was owner (by marriage) of a pub named The Marquis of Granby.

Many names for pubs that appear nonsensical may have come from corruptions of old slogans or phrases, or of certain nobles' or politicians' names. Often, these corruptions evoke a visual image which comes to signify the pub; these images had particular importance for identifying a pub on signs and other media before literacy became widespread. An example is the pub name The Goat and Compasses, which is said to be a corruption of the phrase "God encompasseth us". Another example of a mistaken pub name is the Oyster Reach pub in Ipswich, England. This pub spent several decades being called the Ostrich, before historians informed the owners of the original name. More possible but uncorroborated corruptions include "The Bag o'Nails" (Bacchanals), "Elephant and Castle", (Infanta de Castile), "The Cat and the Fiddle" (Caton Fidele)[38] and "The Bull and Bush", which purportedly celebrates the victory of Henry VIII at "Boulogne Bouche" or Boulogne-sur-Mer Harbour. While these corruptions are amusing there are usually more substantiated explanations available.

A too-obviously humorous name is likely to be a recent coining of a marketing executive, rather than traditional. This is especially true for names with unsubtle double-entendres or names that have elements common to all the pubs in a particular chain (eg "XXXX and Firkin").

Types of pubs

Tied houses and free houses in Britain

After the development of the large London Porter breweries in the 18th century, the trend grew for pubs to become tied houses which could only sell beer from one brewery (a pub not tied in this way was called a Free house). The usual arrangement for a tied house was that the pub was owned by the brewery but rented out to a private individual (landlord) who ran it as a separate business (even though contracted to buy the beer from the brewery). Another very common arrangement was (and is) for the landlord to own the premises (whether freehold or leasehold) independently of the brewer, but then to take a mortgage loan from a brewery, either to finance the purchase of the pub initially, or to refurbish it, and be required as a term of the loan to observe the solus tie. A growing trend in the late 20th century was for the brewery to run their pubs directly, employing a salaried manager (who perhaps could make extra money by commission, or by selling food).

Most such breweries, such as the regional brewery Shepherd Neame in Kent and Young's in London, control hundreds of pubs in a particular region of the UK, whilst a few, such as Greene King, are spread nationally. The landlord of a tied pub may be an employee of the brewery—in which case he would be a manager of a managed house, or a self-employed tenant who has entered into a lease agreement with a brewery, a condition of which is the legal obligation (trade tie) only to purchase that brewery's beer. This tied agreement provides tenants with trade premises at a below market rent providing people with a low-cost entry into self-employment. The beer selection is mainly limited to beers brewed by that particular company. A Supply of Beer law, passed in 1989, was aimed at getting tied houses to offer at least one alternative beer, known as a guest beer, from another brewery.This law has now been repealed but while in force it dramatically altered the industry.

The period since the 1980s saw many breweries absorbed by, or becoming by take-overs, larger companies in the food, hotel or property sectors. The low returns of a pub-owning business led to many breweries selling their pub estates, especially those in cities, often to a new generation of small chains, many of which have now grown considerably and have a national presence. Other pub chains, such as All Bar One and Slug and Lettuce offer youth-oriented atmospheres, often in premises larger than traditional pubs.

A free house is a pub that is free of the control of any one particular brewery. "Free" in this context does not necessarily mean "independent", and the view that "free house" on a pub sign is a guarantee of a quality, range or type of beer available is a mistake. Many free houses are not independent family businesses but are owned by large pub companies. In fact, these days there are very few truly free houses, either because a private pub owner has had to come to a financial arrangement with a brewer or other company in order to fund the purchase of the pub, or simply because the pub is owned by one of the large pub chains and pub companies (PubCos) which have sprung up in recent years. Some chains have rather uniform pubs and products, some allow managers some freedom. Wetherspoons, one of the largest pub chains does sell large amounts of a wide variety of real ale at low prices - but its pubs are not specifically "real ale pubs", being in the city centre to attract the Saturday night crowds and so also selling large quantities of alcopops and big-brand lager to large groups of young people.

Companies and chains

Organisations such as Wetherspoons and the Eerie Pub Company, were formed in the UK since changes in legislation in the 1980s necessitated the break-up of many larger tied estates. A PubCo is a company involved in the retailing but not the manufacture of beverages, while a Pub chain may be run either by a PubCo or by a brewery. If the owning company is not a brewery, then the pub is technically a 'free house', however limited the manager is in his/her beer-buying choice.

Pubs within a chain will usually have items in common, such as fittings, promotions, ambience and range of food and drink on offer. A pub chain will position itself in the marketplace for a target audience. One company may run several pub chains aimed at different segments of the market. Pubs for use in a chain are bought and sold in large units, often from regional breweries which are then closed down. Newly acquired pubs are often renamed by the new owners, and many people resent the loss of traditional names, especially if their favourite regional beer disappears at the same time. A small number of pub chains (usually small ones) are noted for the independence they grant their managers, and hence the wide range of beers available.

Theme pubs

Pubs that cater for a niche audience, such as sports fans or people of certain nationalities are known as theme pubs. Examples of theme pubs include sports bars, rock pubs, biker pubs, Goth pubs, strip pubs, and Irish pubs (see below).

In Canada the majority of theme pubs are referred to as bars, such as 'biker bar', 'sports bar', 'gay bar', 'strip bar', etc. Pubs centred on dance floors featuring DJ's or less often, live music, are usually referred to as 'dance clubs'.

In the U.S., almost all drinking establishments called "pubs" are simply bars with an Irish or British theme.[citation needed]

Country pub

A "country pub" by tradition is a rural public house. However, the distinctive culture surrounding country pubs, that of functioning as a social centre for a village and countryside community, has been changing over the last thirty or so years. In the past, many rural pubs provided opportunities for country folk to meet and exchange (often local) news, while others - especially those away from village centres - existed for the general purpose, before the advent of motor transport, of serving travellers as coaching inns.[39]

In more recent years, however, many country pubs have either closed down, or have been converted to establishments more intent on providing seating facilities for the consumption of food, than that of the local community meeting and convivially drinking.[40]

Organisations such as CAMRA (Campaign for Real Ale) show real concern that these trends be reverted before the inevitable disappearance of the country pub. See the Globe Inn for an authentic rural British public house.[41]

UK pubs of interest [42]

Contenders for the smallest pub in the UK include:

- The Nutshell in Bury St Edmunds

- The Lakeside Inn, Southport

- The Little Gem, in Aylesford, Kent.

The largest pub in the UK is The Regal, Cambridge, converted from a former cinema.

Oldest pub contenders include:

Pubs outside of Britain

- For Pubs in North America see Pubs in the United States

- For Pubs in Australia see Australian pubs

- For Irish pubs see Public houses in Ireland

Although "British" or "Irish" pubs found outside of Britain and its former areas of influence are, as previously mentioned, often themed bars owing little to the original British public house, a number of "true" pubs may be found around the world. In Denmark - a country, like Britain, with a long tradition of brewing - a number of pubs have opened which eschew "theming", and who instead focus on the business of providing carefully conditioned beer, often independent of any particular brewery or chain, in an environment which would not be unfamiliar to a British pub-goer. Some go to the considerable trouble of importing British cask ale, rather than kegs, in order to provide the full British real ale experience to their customers. This newly-established Danish interest in British cask beer and the British pub tradition is reflected by the fact that some 56 British cask beers were available at the 2008 European Beer Festival in Copenhagen, which was attended by more than 21,000 people.

In popular culture

Inns and taverns feature throughout English literature and poetry, from Chaucer onwards. All the major soap operas on British television feature a pub, with their 'pub' becoming a household name. The Rovers Return is the pub on Coronation Street, the British soap broadcast on ITV. The Queen Vic (short for the Queen Victoria) is the pub on EastEnders, the major soap on BBC One, while The Bull in The Archers and the Woolpack on Emmerdale are also central meeting points. The sets of each of the three major television soap operas have been visited by royalty, including Queen Elizabeth II. The centrepiece of each visit was a trip into the Rovers, the Vic or the Woolpack to be offered a drink.

Much of the plot-line in British film Shaun of the Dead involves the characters trying to reach their local public house, The Winchester, to escape a zombie invasion.

Another famous fictional pub is The Nag's Head featured in the BBC sitcom Only Fools and Horses.

British comedian Al Murray's best-known character is a comic right-wing pub-owner, "The Pub Landlord", not necessarily a representation of the southern-English pub landlord.

US president George W. Bush fulfilled his ambition of visiting a 'genuine English pub' during his November 2003 state visit to the UK when he had lunch and a pint of non-alcoholic lager with British Prime Minister Tony Blair at the Dun Cow pub in Sedgefield, County Durham.

Lock-in

A "lock-in"' is when the owner of a public house allows a number of patrons to continue staying in the pub after the legal closing time.

The origin of the lock-in was a reaction to changes in the licensing laws in England and Wales in 1915, which curtailed opening hours to stop factory workers turning up drunk and harming the war effort. Since 1915 the licensing laws changed very little, leaving the United Kingdom with comparatively early closing times. The tradition of the lock in therefore remained and is on the whole a peculiarly British concept.

The attraction for many was that lock-ins were secret, a conspiracy between publican and patron. Also, they were exclusive, usually with only a few select regulars. The lock-in became a tradition. While publicans risked losing their licences by allowing them, police often turned a blind eye if things were kept low key.[citation needed]

As a result of the Licensing Act 2003, premises may apply to extend their opening hours beyond 11 pm, allowing round-the-clock drinking and removing much of the need for lock-ins.

In other areas, a “lock-in” occurs when a violent, or potentially-violent patron is removed from the premises, and the doors are deadlocked to prevent the individual(s) from re-entering, and to prevent patrons inside from leaving for a short duration so as to prevent contact with aggressors (as a measure of duty of care). During the lock-in period, it is often a traditional courtesy of the venue to provide free drinks and snacks. This practice depends on the local public liability laws and is far less common where bouncers are utilised.[citation needed]

Ireland

Irish pubs are known for their atmosphere or "craic".[43] In Irish, a pub is referred to as teach tábhairne ("tavern-house") or teach [an] óil ("house of drink").

The general history and tradition of the Irish pub mirrors that of the UK.[44]

See also

- Bar

- Biergarten (aka Beer garden)

- Coffeehouse

- Crâşmă or Cârciumã Romanian equivalent (of some sorts) of a public house

- Inn

- Izakaya

- Kopi tiam, coffee shop

- Restaurant

- Tavern

- Taxicab

- Beer hall, a German pub

- Pub sports

- Beer garden

- Evening Standard Pub of the Year, an annual award in London

- Pub crawl

- Tied house

- Cider house

References

Notes

- ^ History of the pub Beer and pub association; Accessed 03-07-08

- ^ Public House Brittanica.com; Subscription Required; Accessed 03-07-08

- ^ "Summary of Licensing Board Policies". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ http://www.beerandpub.com/pub_facts.aspx British Beer and Pub Association

- ^ http://www.communityalertonpubs.org.uk/ website with comments box

- ^ "Great British Pub".

- ^ "The history of the pub".

- ^ "Company History".

- ^ Gin Lane British Museum

- ^ "Beer Houses". AMLWCH History.

- ^ "Beer Houses". History UK.

- ^ "Beer houses". Old Cannon Brewery.

- ^ Defence of the Realm Act

- ^ Seabury, Olive. "The Carlise State Management Scheme: Its Ethos and Architecture. A 60 year experiment in regulation of the liquor trade". ISBN 978-1-904147-30-5.

- ^ Licensing Act 2003 (c. 17)

- ^ "Hospital alcohol admissions soar". BBC NEWS. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ "Ban on smoking in pubs to come into force on 1 July - UK Politics, UK - The Independent". www.independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ "Wetherspoons pub chain profit drops on smoking ban - International Herald Tribune". www.iht.com. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Scottish & Newcastle Agrees to Be Bought and Split - New York Times

- ^ Time Gentlemen Please!

- ^ In the Pub - CAMRA

- ^ Darts - Online Guide

- ^ Skittles, Nine Pins - Online guide

- ^ Dominoes - Online Guide

- ^ Bar Billiards - Online Guide

- ^ Aunt Sally - The Online Guide

- ^ Nine Mens Morris, Mill - Online guide. History and Where to Buy

- ^ Ringing the Bull - History and information

- ^ History of Pool and Carom Billiards - Online Guide

- ^ Billiards and Snooker - Online guide

- ^ Shove Ha'penny - Online Guide

- ^ Bat and Ball Games - Online Guide

- ^ a b lookupapub.co.uk - Pub Food

- ^ Ploughman's Lunch - Icons of England

- ^ Better Pub Grub The Brooklyn Paper

- ^ Pub grub gets out of pickle The Mirror

- ^ "Is the gastropub making a meal of it? - Telegraph". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ "E. Cobham Brewer 1810–1897. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. 1898". Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ http://www.southernlife.org.uk/country_pub.htm What the country pub is by tradition

- ^ http://www.curmudgeon.org.uk/misc/deathpub.html The more recent developments of the country pub

- ^ http://www.newarkcamra.org.uk/bgp/pubs/cull.htm CAMRA's concerns

- ^ Evans, J., The Book of Beer Knowledge, CAMRA (2004), ISBN 1852491981

- ^ What's the Craic?

- ^ Gaelic Inns - History of Irish & English Pubs

Trade Signs of Essex by Miller Christie pub 1887.[1]

Bibliography

- Beer and Britannia: An Inebriated History of Britain, Peter Haydon, Sutton (2001)

- Beer: The Story of the Pint, Martyn Cornell, Headline (2003)

- The English Pub, Michael Jackson, Harper & Row(1976).